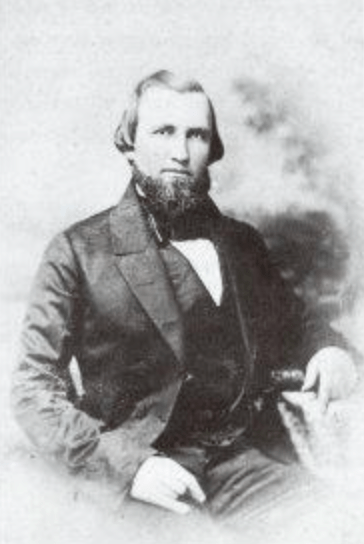

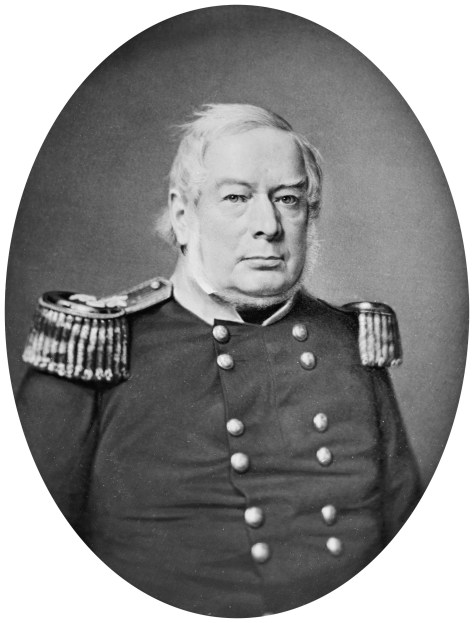

This letter was written by Sylvester Churchill (1783-1862) who began his military career at the outbreak of the War of 1812. He was appointed a 1st Lieutenant in the 3rd US Artillery and served with distinction, rising progressively in rank until 1847 when he was breveted Brigadier General for his services in the Mexican-American War. At the beginning of the Civil War he had been Inspector General for over 20 years. He retired in September 1861. He was married to Lucy Hunter (1786-1862).

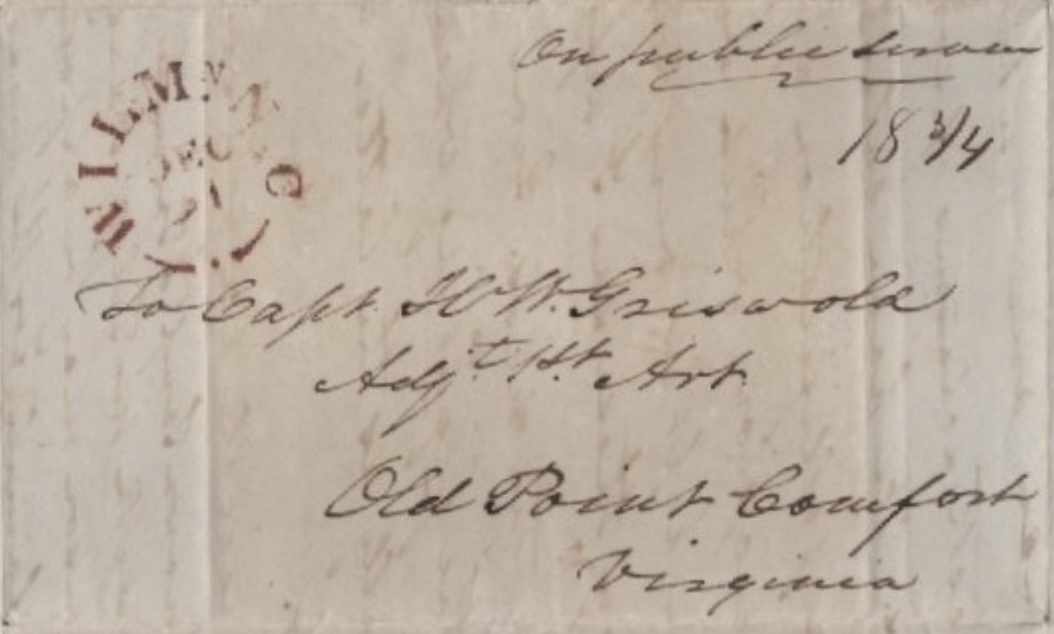

The letter was adressed to Capt. Henry William Griswold (1795-1834), an 1815 graduate of the US Military Academy and a career artillery officer. At the time this letter was written in December 1830, he was in garrison at Ft. Monroe (Old Point Comfort, Va,) were he was Captain of the 3rd US Artillery. Griswold wrote a letter of recommendation for Edgar Allen Poe to enter West Point where Poe was stationed in 1828-29.

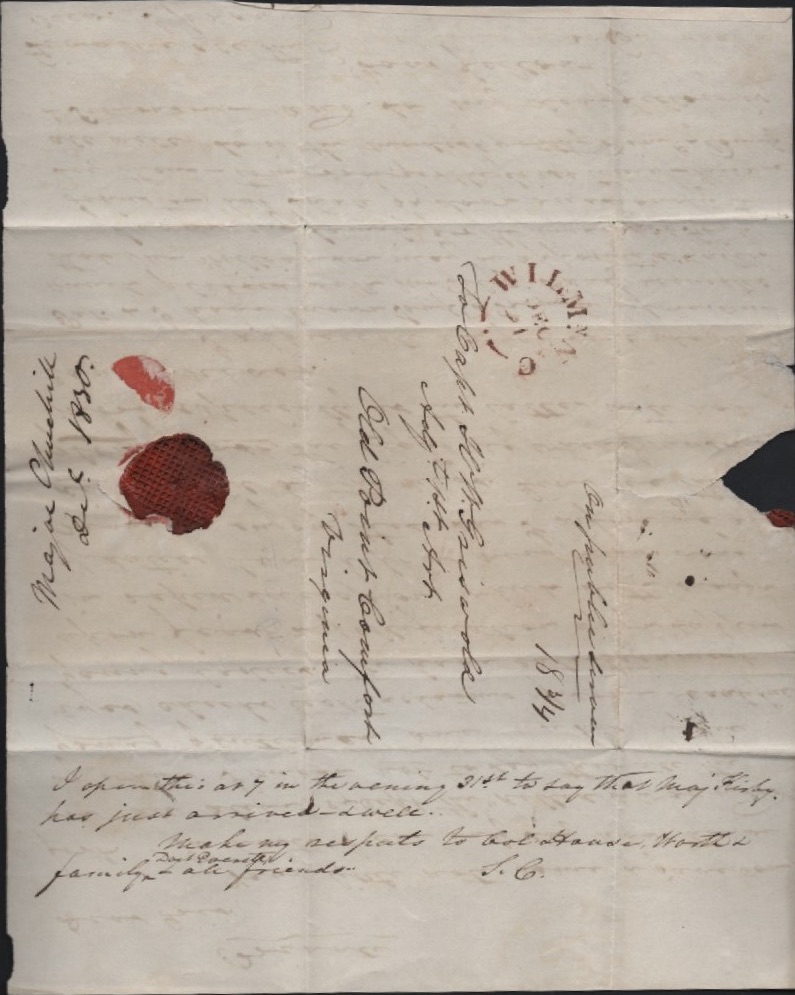

Churchill drafted the letter during the Holiday Season of 1830 in Wilmington, North Carolina, as indicated by the content and postal markings. While he does not disclose the specifics of his long-term assignment, it is evident that it pertained to military service, as he included the “Private” sheet directed to Griswold amidst what was likely official correspondence. He notes that his family was safely settled at Fort Johnson—a historic Revolutionary War fort situated on the Clinch River near Wilmington. His assignment may have been connected to Fort Caswell, which was under construction during that period. He hints at some fear of being “kilt dead by nigs” which explains why he kept his family at Fort Johnson. I’m not aware of any particular slave revolt at that time but, in general, there was a constant fear among slave owners throughout this period of slave uprisings as the slaves greatly outnumbered the white inhabitants. As a Northerner, his presence among a large slave population may have heightened his anxiety.

In the previous year Churchill had been on assignment to perform an assessment of the value of the Mount Dearborn Armory situated on an island in the Catawba River in Chester County. South Carolina. This armory was intended to be comparable to the ones built at Springfield and Harper’s Ferry but it was never fully completed and it was completely abandoned by 1825. Churchill was paid $8 a day for 8 days to determine the property value when it was sold back to the State of South Carolina. The state subsequently sold it to Daniel McCullough who built a cotton factory on the site which was destroyed by Sherman in 1865. [See: Mount Dearborn Armory]

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Private

[December 1830]

Dear Gris–

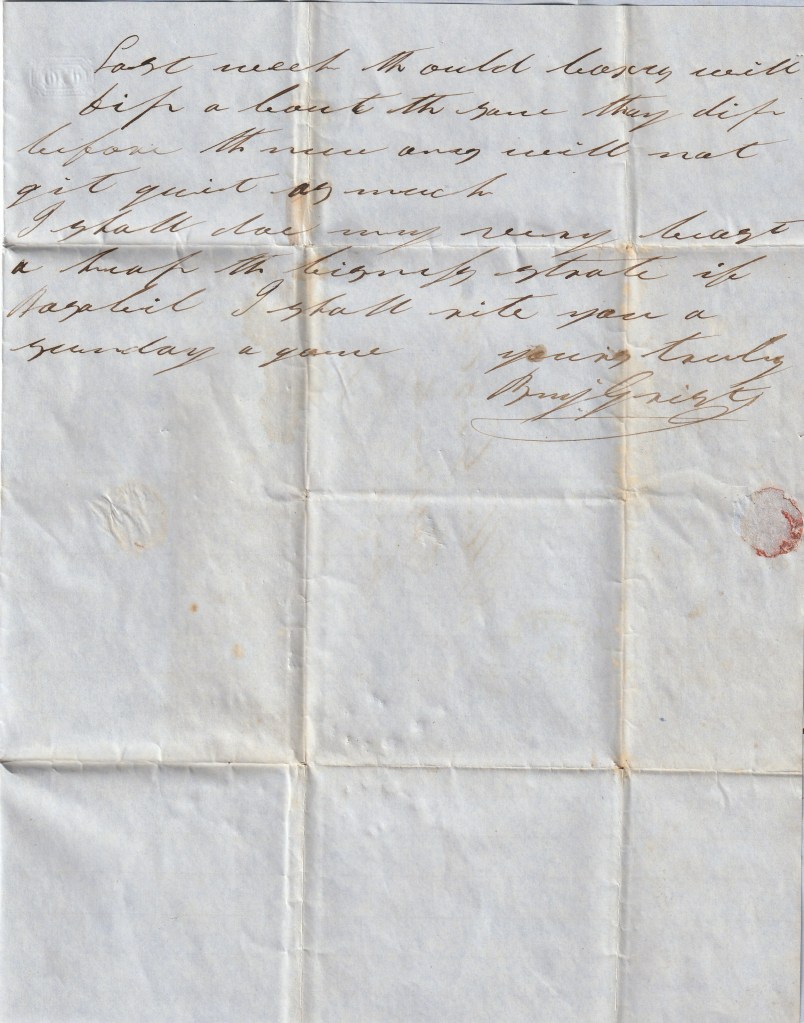

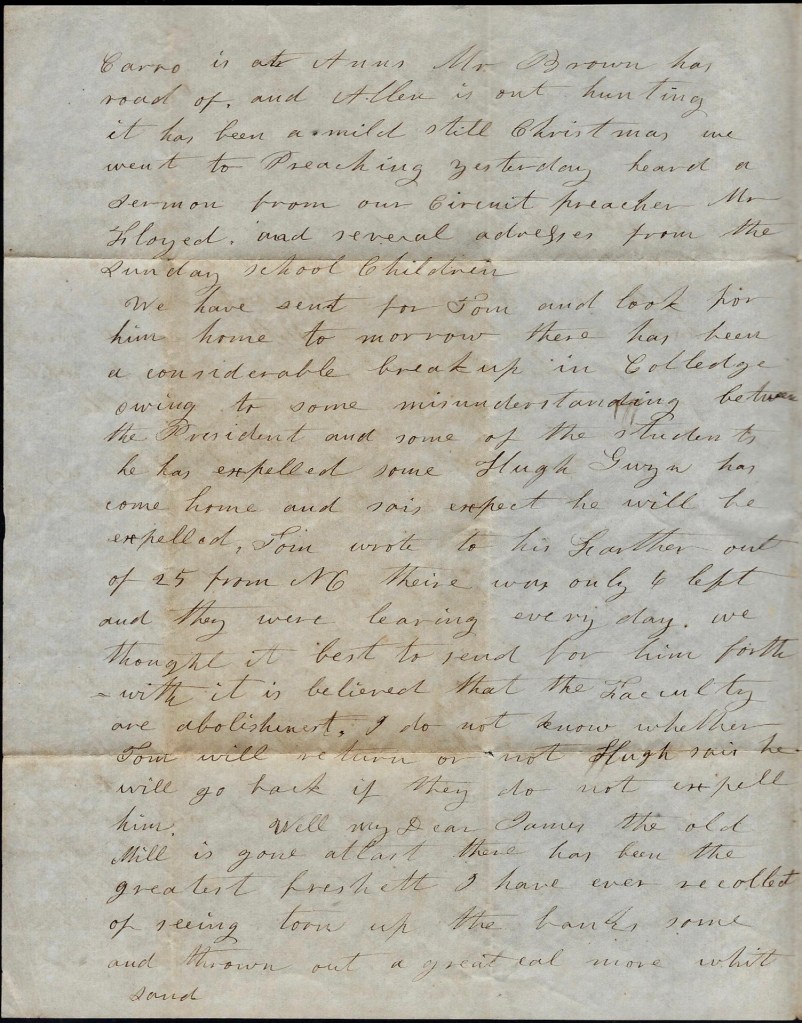

Your little note came & gave comfort. In haste I can only say now that we are all alive except the “killed and wounded” by which I mean not to say that all the young gentlemen are unhit by the eyes, cheeks, teeth, & charms of some beautiful young ladies. We have entertainment upon feast & jollification upon suppers in rapid succession, which with enough of duties, have left us very busy. Long may we enjoy these, say I, before we are kilt dead by the nigs. Give me the glory first, the fighting when I must—more especially as the latter will not come—never.

I appreciate all you said about Pat. & I have known Samp. & Trimble 1 before. Am much pleased with Mr. [ ]. Have requested that Mr. Williamson may be appointed sutler.

Leave my family for the present at Fort Johnston, but shall go down occasionally to see them—tomorrow, for the first time. They are all well. So is the modest, worthy Dimock & family & Simonson—and so, my dear fellow, is your fellow, — S. C.

Give me all the news I pray.

I open this at 7 in the evening 31st to say that Maj. Kirby has just arrived & well. My my respects to Col Hand’s, Worth’s family & all friends.

1 This was probably Isaac Ridgeway Trimble (1802-1888) who graduated from the US Military Academy in 1822 and was commissioned a 2nd Lt. of Artillery. He was and engineer and in the 3rd US Artillery before he left the service in 1832 to pursue a career in railroads. He became a Confederate General in the Civil War.