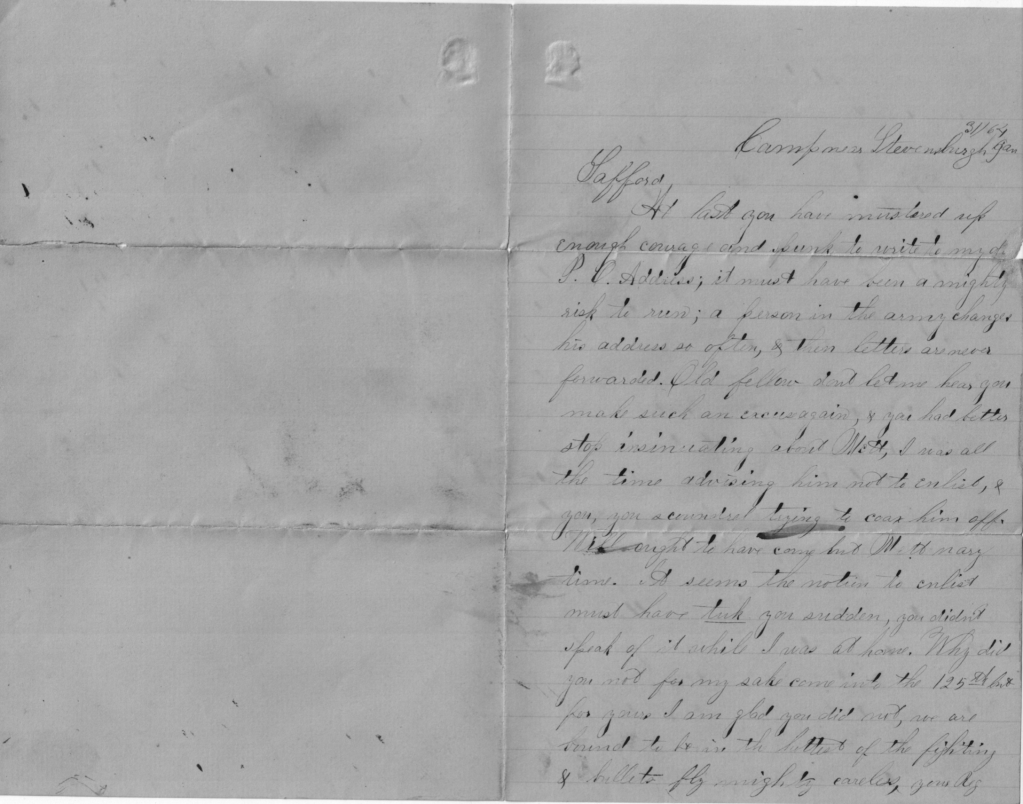

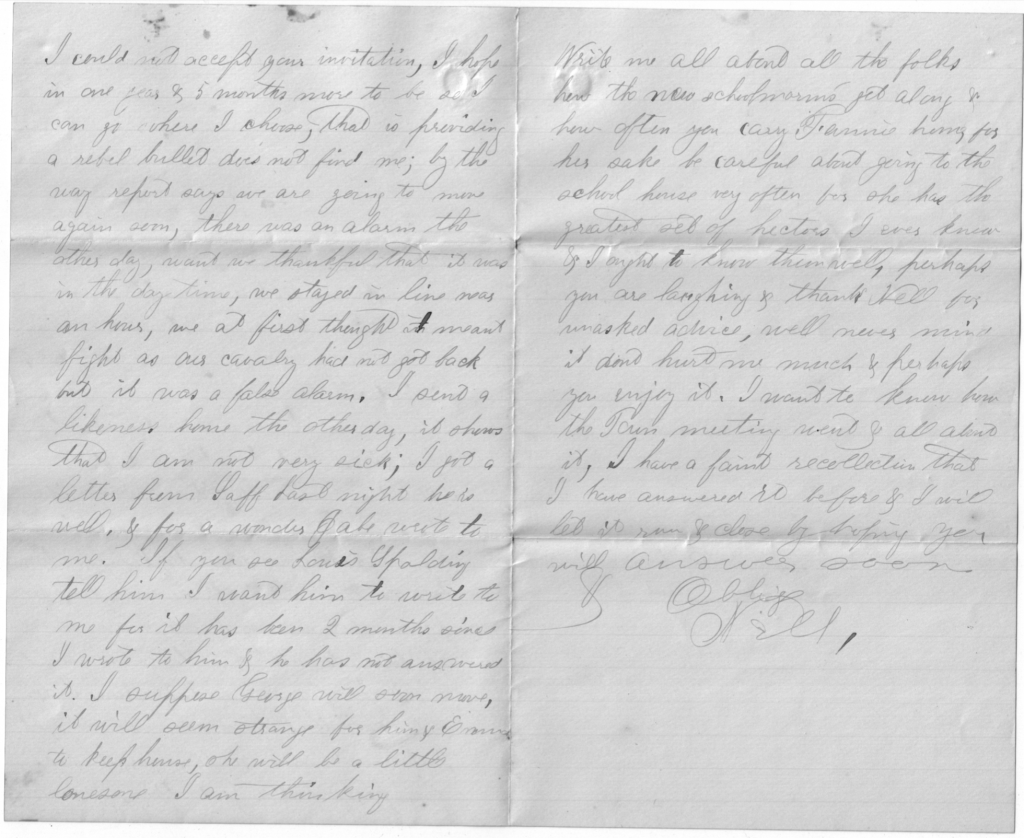

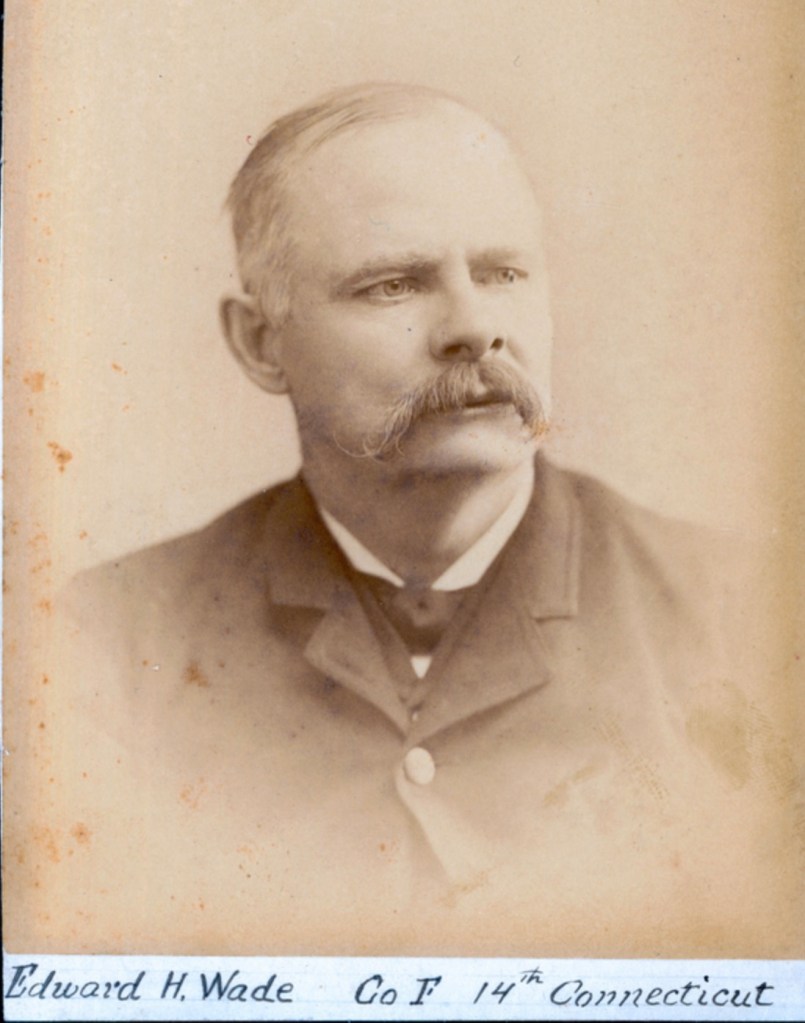

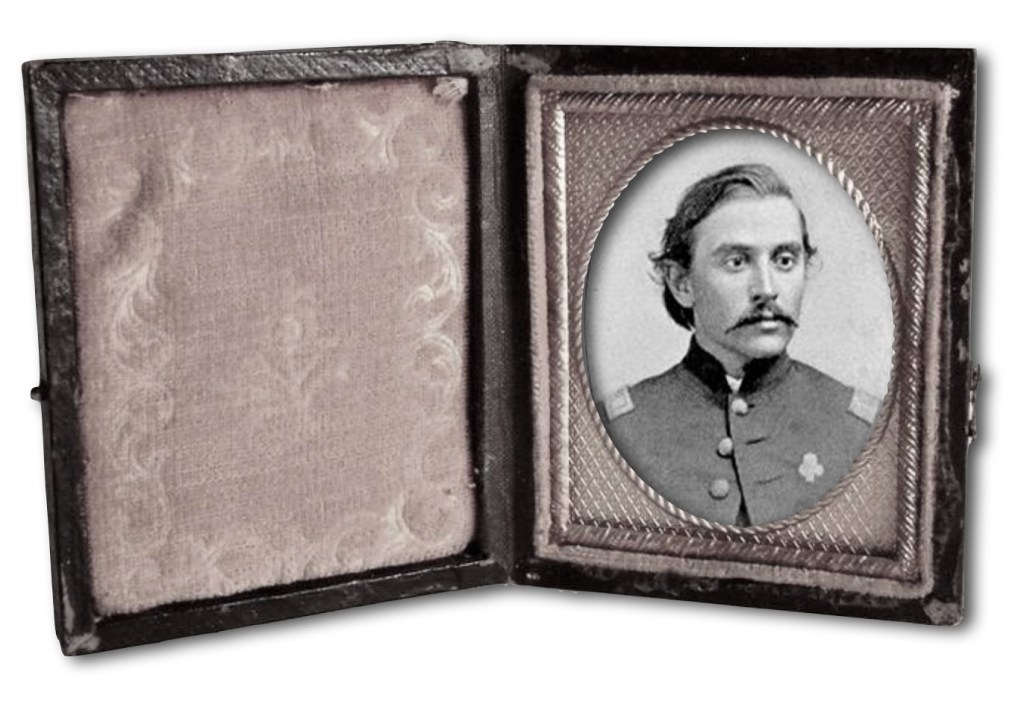

The following letters were written by Edward H. Wade (1836-1897), the son of Amasa Dwight Wade (1795-1870 and Nancy A. Wait (1798-1859) of Northampton, Hampshire county, Massachusetts. Edward wrote the letters to his younger sister, Ellen Nancy Wade (1838-1887), while serving as a corporal in Co. F, 14th Connecticut Infantry.

Edward was working as a printer in Northampton when he enlisted as a private in the 14th Connecticut on 8 August 1862. He was promoted to corporal in early February 1863 and survived the war, mustering out at Alexandria, Virginia, on 31 May 1865. Following his discharge, Edward returned to Northampton, Massachusetts, and resumed his career as a printer.

Some time ago I transcribed & published some letters on Spared & Shared that were written by the captain of Co. F, 14th Connecticut. See—1863-65: Frederick Bartlett Doten to Georgia L. Wells.

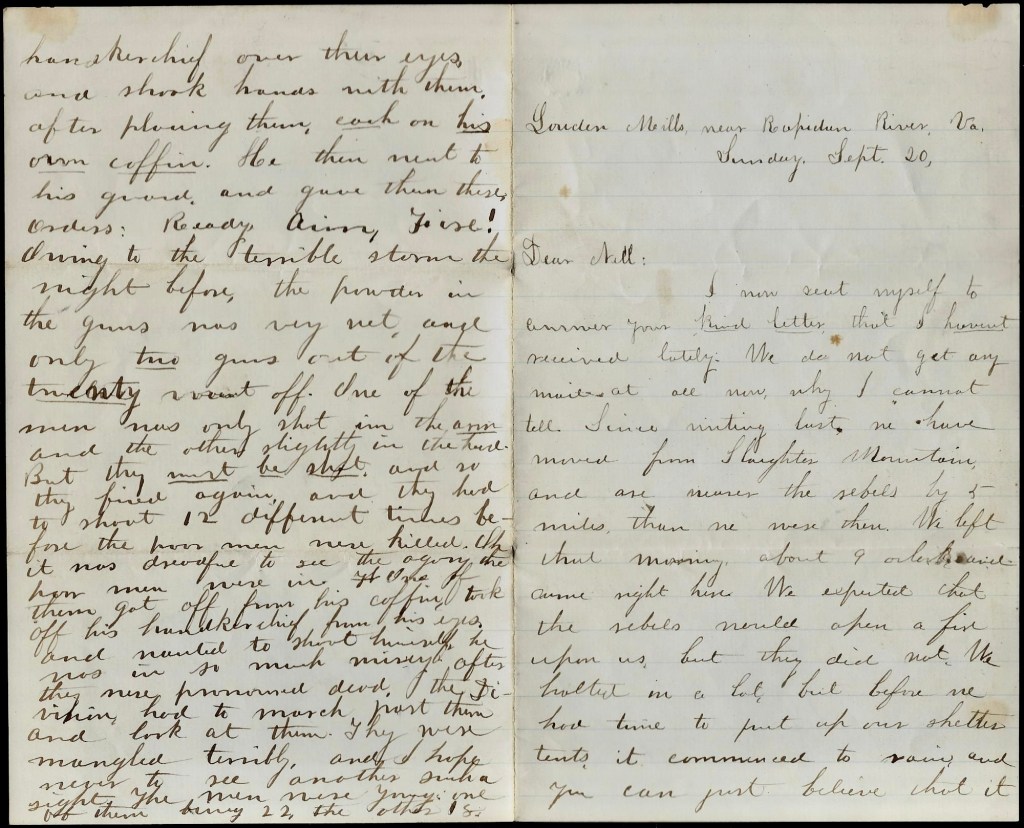

Letter 1

[Edward’s account of the Battle of Chancellorsville. April 28th the regiment moved with the army on the Chancellorsville campaign, in which it saw hard service and lost seriously. At night, May 2d, it was sent with the brigade to the right to check the enemy and hold the ground after the disaster of the Eleventh Corps.]

Monday morning [4 May 1863]

Dear Ellen,

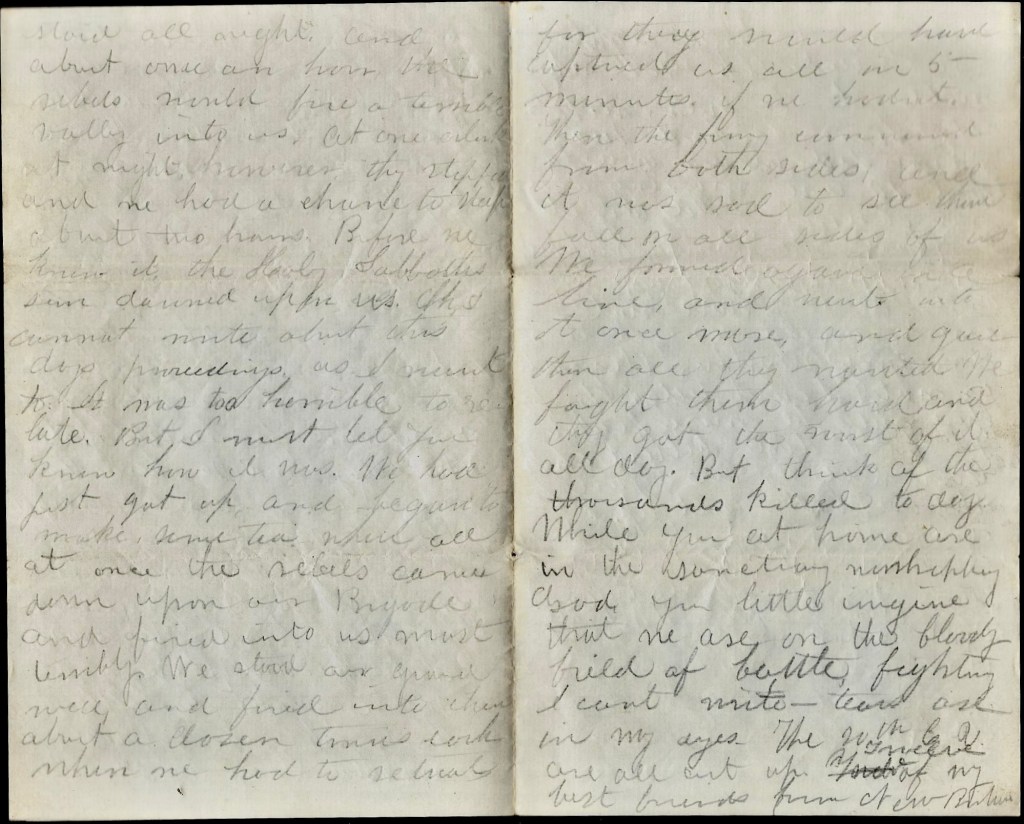

How can I write? Here I am beside the dead and wounded and I don’t know what to write. I sent you a letter Saturday and told you that need not worry about me that we should probably not go into the fight. But the rebels were strongly reinforced from Richmond that day, and so about 4 o’clock we had orders to go right off. We started and went right up to the point where our forces were fighting hard. We was not needed there, and so we went a little to the right in a field of woods. Here we staid all night and about once an hour, the rebels would fire a terrible volley into us. At one o’clock at night, however, they stopped and we had a chance to sleep about two hours.

Before we knew it, the Holy Sabbath sun dawned upon us. Oh, I cannot write about this day’s proceedings as I a want to—it was too horrible to relate. But I must let you know how it was.

We had just got up, and begun to make some tea, when all at once the rebels came down upon our Brigade and fired into us most terribly. We stood our ground well, and fired into them about a dozen times each when we had to retreat for they would have captured us all in 5 minutes if we hadn’t. Then the firing commenced from both sides and it was sad to see them fall on all sides of us. We formed again in a line and went into it once more, and give them all they wanted. We fought them hard and they got the worst of it all day. But think of the thousands killed today. While you at home are in the sanctuary worshipping God, you little imagine that we are on the bloody field of battle fighting.

I can’t write—tears are in my eyes. The 20th C. Volunteers are all cut up. Twelve of my best friends from New Britain were in it and eight are killed. Oh God, when will it be over with. We have had two wounded in our own company but 10 are missing and we cannot find any sign of them. The firing stopped [ ] o’clock last night and they have not commenced as yet this morning. Whether they will or not, I can’t tell. I think there will be more fighting yet but I don’t believe this regiment will go in again for they are badly cut up. I don’t know as I will have a chance to send this today. If I can’t, I will write again. Don’t fear for me. I am all right so far, Goodbye, — Edward

I can send this now so goodbye. I will write again soon.

Letter 2

Camp near Falmouth Va.

May 21st 1863

Friend Nellie,

For as such I take the liberty to address you for I have heard your brother, who is a dear friend of mine, speak of you so often that I feel as though I had been acquainted with you for years, you must pardon me for thus intruding upon your time and attention. I should not have presumed upon the thought of writing to you but with the consent of your brother by whom I feel proud to be called friend. Yes, he is one whom anyone might feel proud to call him friend, and of whom any young lady might feel proud of as a brother. And I am glad to say that he is one who faithfully discharges his duties both to his God and his country, and the prayer of his humble friend is that he may be spared through all the trials and dangers of a soldiers life to return to his dear father and sisters and once more bring joy and happiness to their now lonely fireside. But if God should not see fit to reunite you on earth, may you all live so that at the judgement day you may meet an unbroken family around the mercy seat of God on high and may I be so happy as to be permitted to witness your joy. Such is the prayer and hope of your humble friend, — L. F. Norton

[In different hand]

Dear Nell: — Such are the remarks of a kind friend of mine who sat at my side this morning while I read part of the letter which I received from you last night, written on your birthday. After I read what I chose, he took a sheet of paper and asked what I wanted he should write to you. I told him anything he chose, when he took this sheet and wrote what is on it. It is very flattering to me, I think, but of course it is all the truth—it must be. Hain’t I a love of a feller! The writer is a mighty good fellow, and is now acting Orderly Sergeant of the company. I was not much acquainted with him in Connecticut but since we have come out here, we have tented together, and are now fast friends. I hope we may both live to return home, withal he may be enabled to visit us at our home, and then we will have a good old fashioned time. I calculate if I ever get home to have a good many friends who are with me here to make me a visit. I want to show you what the 14th is composed of and the first to visit me will be Lucius F. Norton.

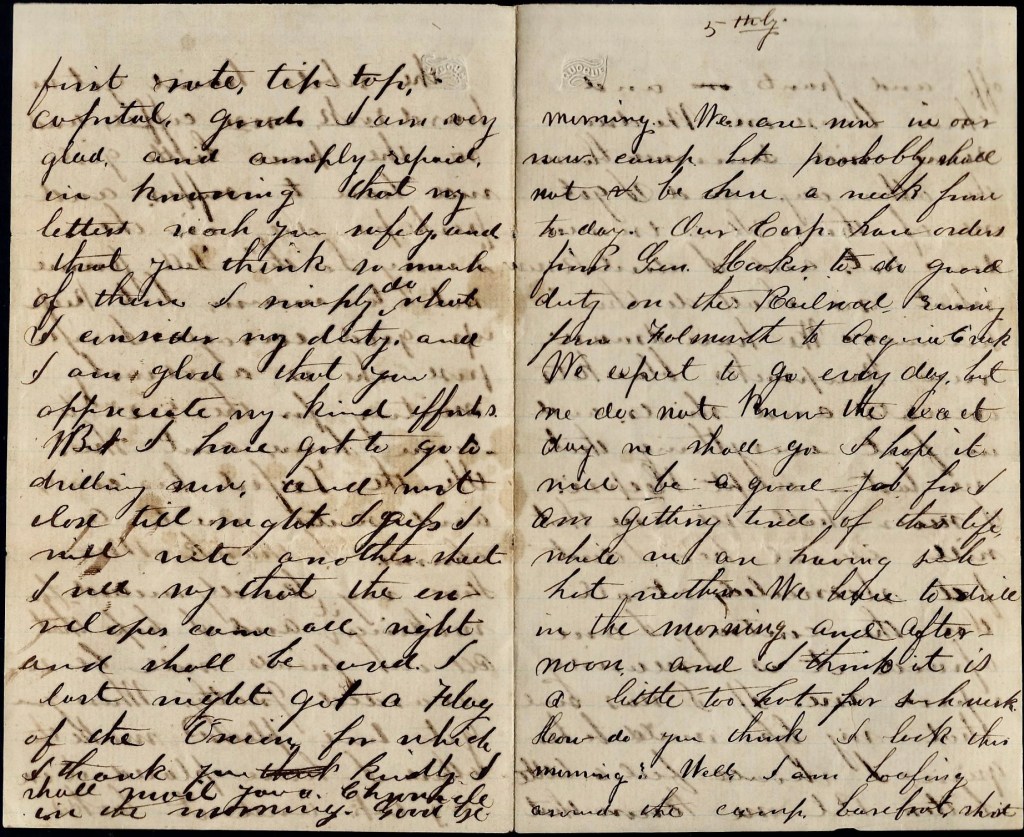

Well, what shall I write to you about this time? I wrote to you the first of the week but I got a good letter from you last night and I cannot but answer it this morning. We are now in our new camp but probably shall not be here a week from today. Our Corp have orders from Gen. Hooker to do guard duty on the railroad running from Falmouth to Acquia Creek. We expect to go every day but we do not know the exact day we shall go. I hope it will be a good job for I am getting tired of this life while we are having such hot weather. We have to drill in the morning and afternoon and I think it is a little too hot for such work.

How do you think I look this morning? Well. I am loafing around the camp barefoot, shoes off, and pants and thin blouse on. We drew some nice summer blouses the other day and I got one of them. It is tremendous hot and I don’t know what we shall do this summer. We have drawn new knapsacks, blankets, overcoats, and shirts, and in fact everything that we lost—except Hepze. 1 I never shall see one that will equal her. I don’t feel reconcided at all. On the contrary, I am afraid it is wearing upon me. If I was sure that my loss would be her gain, I should feel a little better. But we know that the rebels hain’t got no hard tack nor coffee and so the poor little girl will have to suffer and perhaps die in the “Sunny South.” Tell Jennie not to mourn but keep up good courage. I suppose she is anxiously waiting for the 52nd to come home, ain’t she?

Oh, the [blue] trefoil [badge] has come and suits me to a charm. I thank Mrs. Stone very kindly indeed for making it and I hope that all our friends will be rewarded greatly. When you get time, please make the others. I have placed it on my cap and it looks first rate—tip top—capital good! I am very glad and amply repaid in knowing that my letters reach you safely and that you think so much of them. I simply do what I consider my duty and I am glad that you appreciate my kind efforts.

But I have got to go to drilling now, and must close till night. I guess I will write another sheet. I will say that the envelopes came all right and shall be used. I last night got a Flag of the Union for which I thank you kindly. I shall mail you a Chronicle in the morning. Goodbye.

Thursday evening. Well, it is evening and I will now write you a few more lines. I have been made glad this afternoon in receiving a letter from our cousin Marietta at Florence. She writes a capital good letter and I shall answer it soon although I don’t know whether to direct it to Easthampton, Florence, Northampton, or Pugs Hole. Which is it? Won’t you let me know in your next? Ellen, I have had the best cup of coffee tonight that I ever drank. I want you and Jennie to try it and see if it isn’t beautiful. Fill your cup with coffee, then put in a piece of butter about as big as a walnut, then some milk, then break an egg, and put it in. Then sweeten it to your taste. Put in the old crusts and go ahead a drink it down. By jolly, ain’t it good! If eggs weren’t 80 cents a dozen, butter 70 cents a pound, and sugar 18 cents, a soldier even might enjoy himself. But no, it won’t do for them to enjoy themselves. They must be content with salt pork and hard tack. Well, it will all come out right after a while.

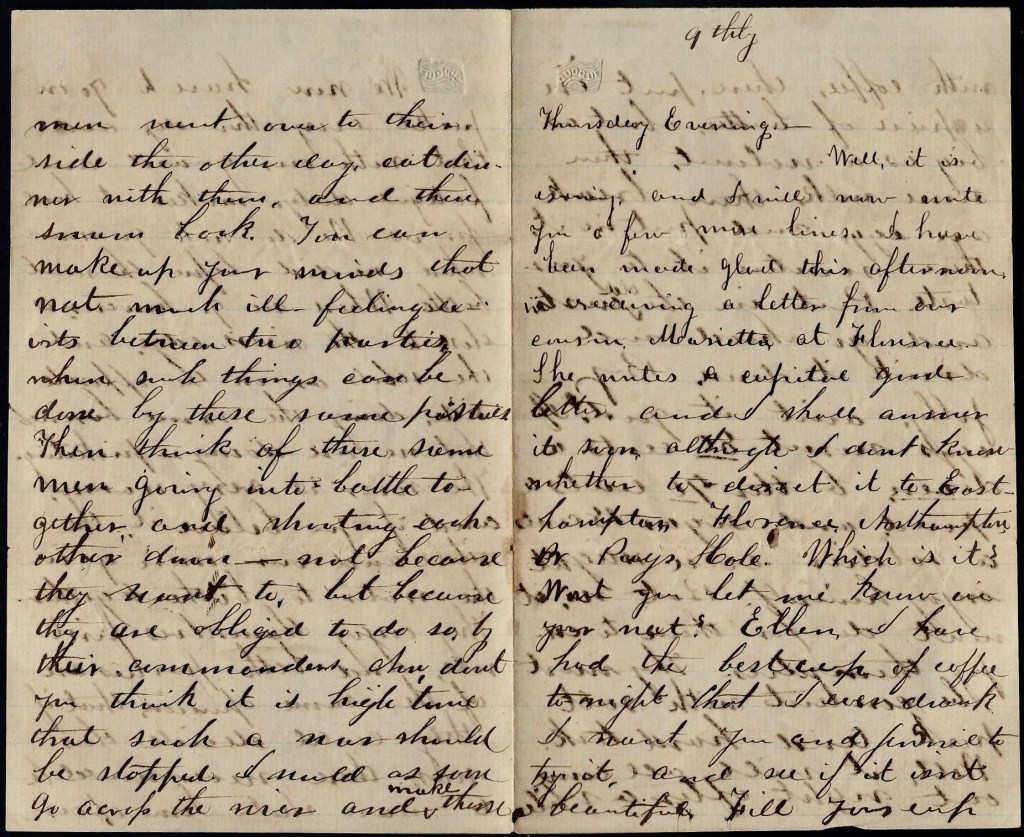

“The [Rappahannock] river is very narrow, and, if you believe it, the rebels and our men go in the water to bathe together. They enjoy themselves first rate and both parties are of the same opinion—that if they could decide this war there never would be a man shot.”

— Edward H. Wade, Co. F, 14th Connecticut, 21 May 1863

We now have to go on picket every other day and that with our guard and fatigue duty make it hard for us. We do not go now where we did before the recent battle. Where we go, however, is close to the [Rappahannock] river’s edge and the rebels are on the opposite side doing the same business that we are doing—picketing. The river is very narrow, and, if you believe it, the rebels and our men go in the water to bathe together. They enjoy themselves first rate and both parties are of the same opinion—that if they could decide this war there never would be a man shot. Some of our men went over to their side the other day, eat dinner with them, and then swam back. You can make up your minds that not much ill-feeling exists between two parties when such things can be done by these same parties. Then think of these same men going into battle together and shooting each other down—not because they want to, but because they are obliged to do so by their commanders. Nell, don’t you think it is high time that such a war should be stopped. I would as soon go across the river and make those men a visit as to go to the 37th Massachusetts or 20th Connecticut.

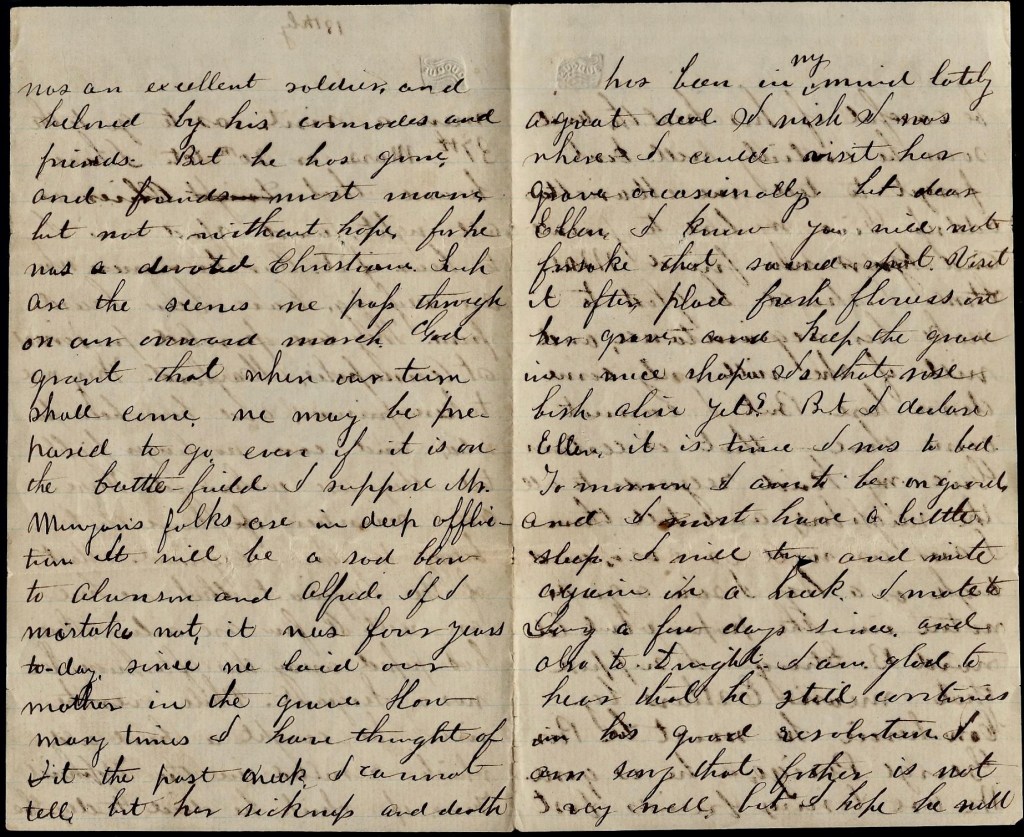

I have heard that Oliver is all right and glad am I to hear of it. Our two men who are missing have been heard from. They are paroled prisoners at Annapolis, Maryland. They were taken prisoners and have been paroled and can no longer fight till they are exchanged. There are seventeen of them that belong to this regiment. Most of the regiment that are here are well. A few are ailing. One has passed away this afternoon. He was a Sergeant. While over the river, he caught a hard cold which resulted in the Typhoid Fever of which he died today. He was an excellent soldier and beloved by his comrades and friends. But he has gone and friends must mourn but not without hope, for he was a devoted Christian. Such are the scenes we pass through on our onward march. God grant that when our turn shall come, we may be prepared to go even if it is on the battlefield.

I suppose Minyon’s folks are in deep affliction. It will be a sad blow to Alanson and Alfred. If I mistake not, it was four years today since we laid our mother in the grave. How many times I have thought of it the past week, I cannot tell, but her sickness and death has been in my mind lately a great deal. I wish I was where I could visit her grave occasionally. But dear Ellen, I know you will not forsake that sacred spot. Visit it often. Place fresh flowers on her grave and keep the grave in nice shape. Is that rosebush alive yet?

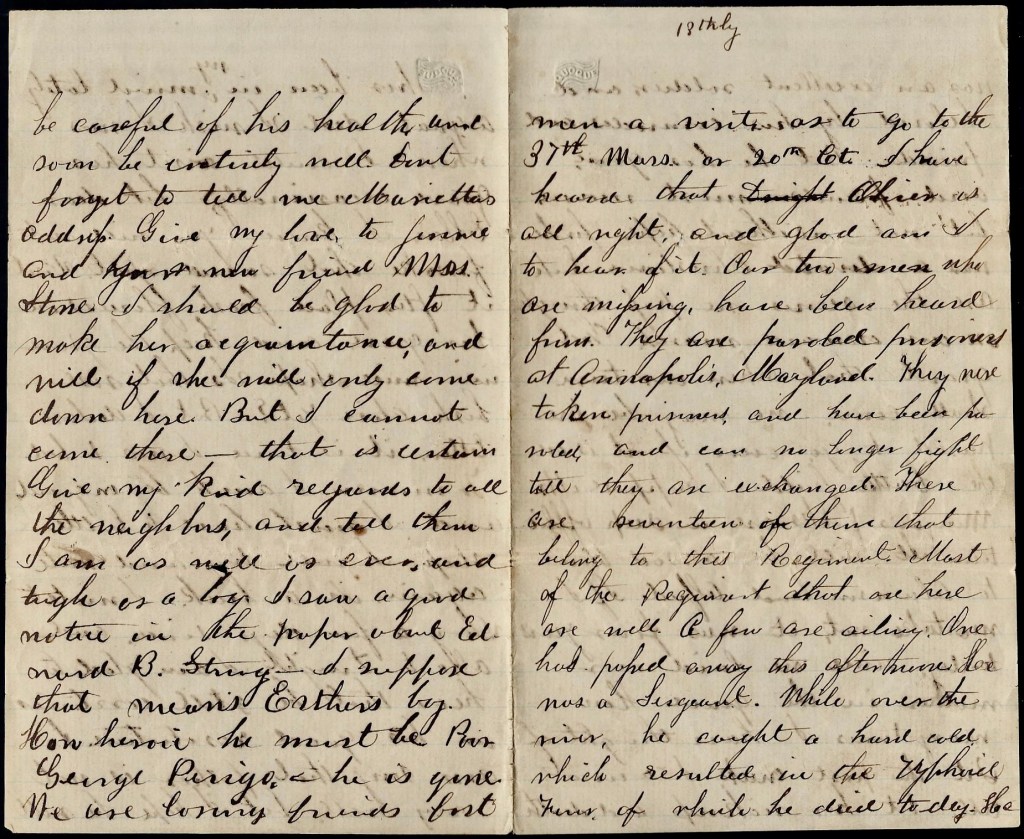

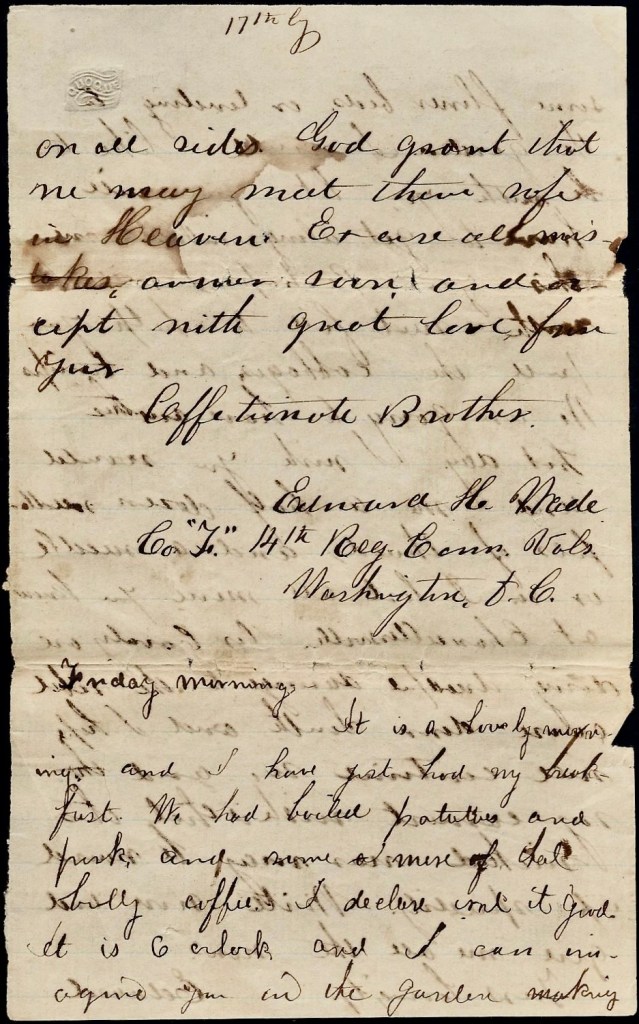

But I declare, Ellen, it is time I was to bed. Tomorrow I am to be on guard and I must have a little sleep. I will try and write again in a week. I wrote to Ivy a few days since and also Dwight. I am glad to hear that he still continues in his good resolution. I am sorry that father is not very well but I hope he will be careful of his health and soon be entirely well. Don’t forget to tell me Marietta’s address. Give my love to Jennie and your new friend Mrs. Stone. I shiould be glad to make her acquaintance and will if she will only come down here. But I cannot come there—that is certain. Give my kind regards to all the neighbors and tell them I am as well as ever and tough as a log. I saw a good notice in the paper about Edward B. Strong. I suppose that means Esther’s boy. How heroic he must be. Poor George Perigo. He is gone. We are losing friends fast on all sides. God grant that we may meet them safe in Heaven. Excuse all mistakes, Answer soon. And accept with great love. From your affectionate brother, — Edward H. Wade, Co. F, 14th Reg. Conn. Vols. Washington D. C.

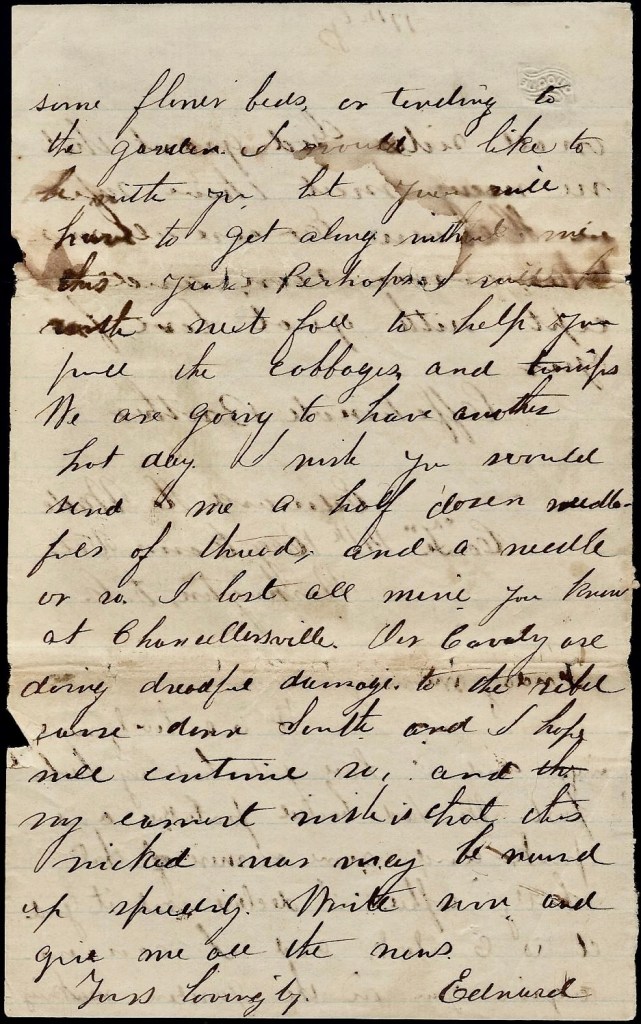

Friday morning. It is a lovely morning and I have just had my breakfast. We had boiled potatoes and pork, and some more of that bully coffee. I declare, isn’t it good. It is 6 o’clock and I can imagine you in the garden making some flower beds or tending the garden. I would like to be with you but you will have to get along without me this year. Perhaps I will be with you next fall to help pull the cabbages and turnips.

We are going to have another hot day. I wish you would send me a half dozen needle fulls of thread, and a needle or so. I lost all mine, you know, at Chancellorsville. Our cavalry are doing dreadful damage to the rebel [ ] down south and I hope will continue so, and my earnest wish is that this wicked war may be wound up speedily. Write soon and give me all the news. Yours lovingly, — Edward

1 Possibly a dog mascot adopted by the company.

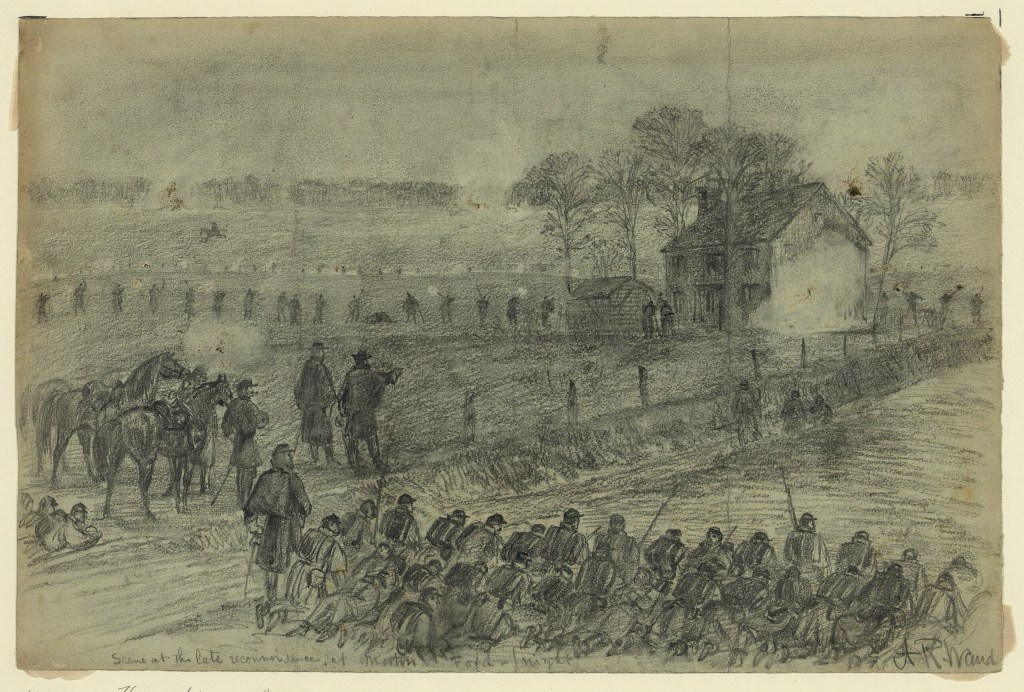

Letter 3

Louden Mills near Rapidan River, Va.

Sunday, Sept. 20 [1863]

Dear Nell,

I now seat myself to answer your kind letter that I haven’t received lately. We do not get any mail at all now. Why, I cannot tell. Since writing last, we have moved from Slaughter Mountain and are nearer the rebels by 5 miles than we were then. We left that morning about 9 o’clock and came right here. We expected that the rebels would open a fire upon us, but they did not. We halted in a lot but before we had time to put up our shelter tents, it commenced to rain and you can just believe that it did rain for about an hour. It then slackened and we put up our tents, but we had no more than got them up when it commenced again and it rained hard and steady all night.

Now I come to a sad part of my letter, but it must be told. Friday, two men belonging to the 14th Regiment were shot for the crime of desertion. 1 They were two of the new men and were brought here about 6 weeks ago, but deserted in two days after they came here. They were found dressed in rebel clothes and after they had had a court martial, were sentenced to be shot on Friday, Sept. 18th in the presence of the Division to which they belonged. I did not wish to see it, but I could not help myself. At 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the whole Division, containing 12 regiments of infantry and two batteries of 6 guns each, were marched into a large open lot. Here we formed a hollow square. About 4 o’clock the guards who were detailed to shoot these poor men came marching along slowly, the two prisoners in the middle of the guard, and the 14th Band playing a funeral dirge. They reached the graves where the coffins were placed by the side of them. The Officer of the Guard then read the sentence of the court-marshal to the prisoners. The Chaplains of the 12th New Jersey and 14th talked and prayed with them and bid them a last farewell. The Officer of the Guard then stepped to them, tied a white handkerchief over their eyes, and shook hands with them, each on his own coffin. He then went to his guard, and gave them these orders: Ready, Aim, Fire! Owing to the terrible storm the night before, the powder in the guns was very wet and only two guns out of the twenty went off. One of the men was only shot in the arm and the other slightly in the head. But they must be shot, and so they fired again, and they had to shoot 12 different times before the poor men were killed. Oh it was dreadful to see the agony the poor men were in. One of them got off from his coffin, took off his handkerchief from his eyes and wanted to shoot himself, he was in so much misery.

After they were pronounced dead, the Division had to march past them and look at them. They were mangled terribly and I hope never to see another such a sight. The men were young—one of them being 22, the other 18. One of the men was a substitute, and the other—a nice looking young man of 19 who was unable to pay his $300—was drafted and had to come. This is what comes of the [ ] of the North, for if they would have been brave enough to come, there would have been no need of a draft, and no substitutes to hire, and there would have been two men more in the Union army.

But I will stop writing on this subject for it makes me sick at heart. When will the North open their eyes and see their danger. Well, we moved our camp from the wet lot to the woods and yesterday our Brigade were detailed to come out on picket and we are the outposts. The Rebel cavalry are close to us on picket also, and ew can talk to them if we choose. I don’t hardly think we shall fight here for the Rebels have a large force here, or across the river rather. They have got an excellent position and have got their rifle pits dug so that if we fought them, we should have to run a great deal of danger and I don’t believe that our Generals will be so foolish as to undertake to get them out of their rifle pits just now. We must flank them or they will give us fits. But I don’t know what they will do althoigh I hope they won’t try it in here.

I am very well. We had a cold night last night and fall is fast coming upon us. I guess we should have to stay here one winter more but I hope not. How do you all do? Oh, I wish I could see you and have a good talk. Wouldn’t our tongues go for a while? I bet you one thing is certain, if I am around here next winter, I shall get a furlough if it is possible. Oh, in my last letter I sent home a picture of a friend of mine who belongs to our company and who is now at home after conscripts. His name is Danford J. Davis. 2 Please save it for me for I want to keep it safe. Capt. [Samuel A.] Moore is going to give me his when he comes back and I shall then send that home. I wish I could get where I could have mine taken.

But I must close. The mail has come and brought me a letter from Marietta. None from you yet. I hope to hear from you soon. Give me all the news. Give my love to all the neighbors, to father and Suzy and Dwight and Olly. Excuse all mistakes and answer soon. I suppose Jennie has got my letter before this, has she not? I would write to Mr. Gus if I had time and could write as I wanted to and give him a description of the shooting of of those two men but it would take more time than I have to spare and I guess I will let it go. Tell father to give my love to Mr. Axtell and tell him I would like to hear from him. And give my love to all the neighbors. From your brother, — Edmund H. Wade

1 The two men from the 14th Connecticut executed on 18 September 1863 were Edward Elliott and George Layton. Their execution were described: Of all the executions, the ones that killed Privates George Layton and Edward Elliott produced the most irritation. It took several tries for the ill-prepared firing squad to deliver the killing blow. The two soldiers, Layton and Edwards, had the shortest terms of service of any of the condemned men. Both had mustered into the ranks of 14th Connecticut on July 18, 1863. Elliott was a twenty-two-year-old draftee and Layton (sometimes written as Laton) was a twenty-year-old substitute who often went by a fake name (either George Joy or Charles Eastman). Late in the afternoon, the 3rd Division, 2nd Corps, formed up to witness Elliott’s and Layton’s deaths. Major General William French, who normally commanded the 3rd Corps, held temporary command of the 3rd Division’s execution proceedings. What historians know about the debacle comes from The Valiant Hours, a memoir written by Private Thomas F. Galwey of 8th Ohio. According to him, the firing squads botched the execution horribly. When all was ready, the two firing parties took position in front of Layton and Elliott. At a command from the provost marshal, the squads pulled their triggers. The first volley struck one of the two deserters (Galwey did not say which one), wounding him slightly. He fell over, bleeding on his coffin. The other condemned man did not receive a scratch. In fact, after he heard the volley, he broke loose from his pinion and snatched the handkerchief from his eyes. Galwey remembered, “A murmur of mingled pity and disgust ran through the division. Most of the pieces had only snapped caps. Here was either wanton carelessness in the Provost Guard or a Providential interposition to save the lives of the men.” General French fumed at the firing squads’ failure. He ordered the un-wounded deserter rebound and re-blindfolded and instructed the squads to reload. In a few minutes, a second volley rang out, but with no different result. This time, the firing squads wounded the injured man a second time (but did not kill him), and they completely missed the un-wounded man, driving him—as Galwey described it—“into a paroxysm of fear and trembling without even hitting him!” Now, an audible groan passed through the division, revealing the soldiers’ abhorrence of the proceedings. Galwey narrated the conclusion: The left-hand squad fired once more, killing the wounded deserter, for he fell back upon his coffin and never stirred again. But the right-hand squad only wounded the unhit man at the next volley. He continued to struggle to free himself of his pinions. The guns had evidently been loaded the evening before and become wet from the rains which fell during the night. The Provost Marshal now brought up his men, one by one, and made them pull the trigger with the muzzle almost touching the unfortunate devil’s head! But strange to relate, they only snapped caps, the victim shivering visibly each time. At last the Provost Marshal himself, drawing his revolver, placed the muzzle at the man’s head and discharged all the barrels of it! This finished the man and he fell over into his coffin and never moved again. General French rode up. As we could plainly see, he was indignant at this clumsy butchery. Artists representing the New York newspapers or magazines made on-the-spot sketches of this horrid affair.” [Source: Tales from the Army of the Potomac, April 21, 2016.]

2 Danford J. Davis was from Berlin, Connecticut. He was killed in the Battle of Morton’s Ford in February 1864.

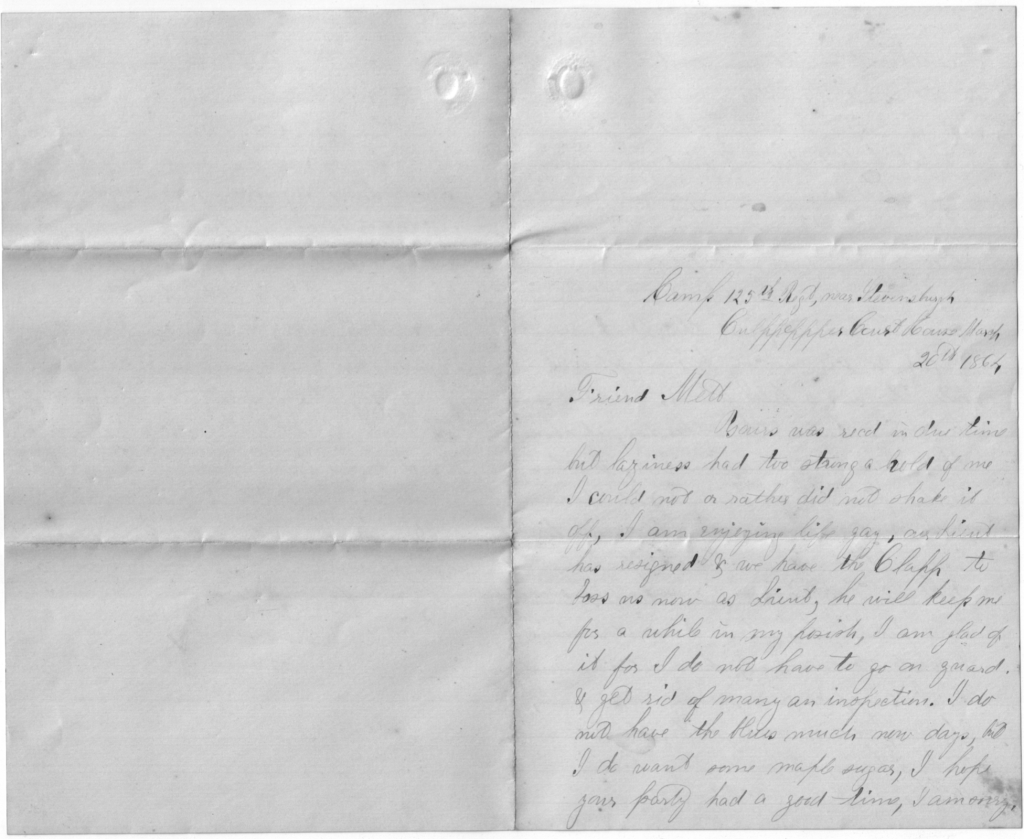

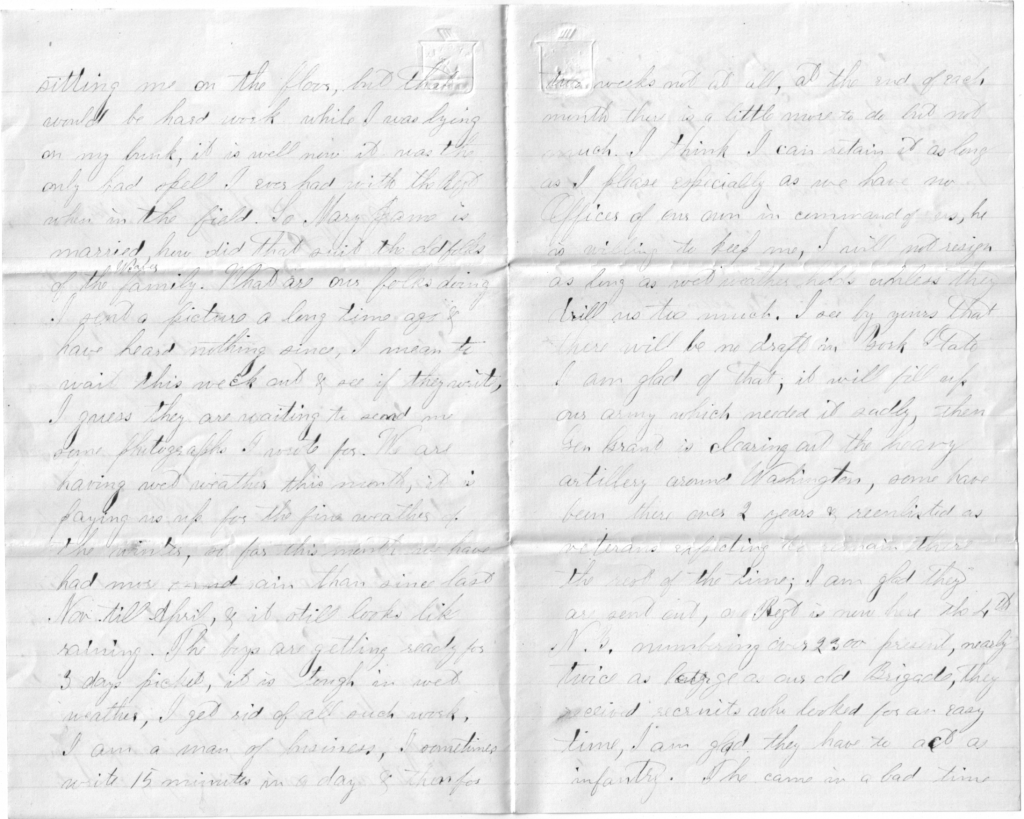

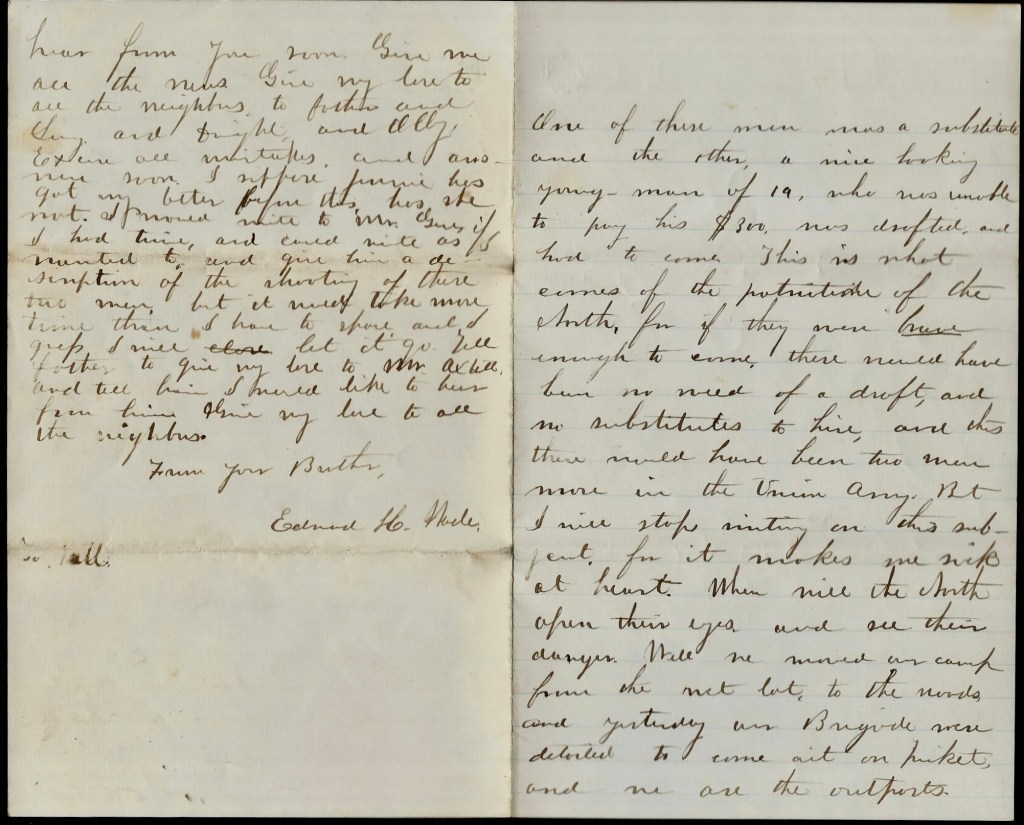

Letter 4

[Wade’s account of the Battle of Morton’s Ford, February 6-7, 1864]

At our old camp

Sunday Evening, Feb. 7 [1864]

Dearest Ellen,

I must write you a few lines, sad as I feel. Oh, Ellen, yesterday was a sad, sad day for the 14th Regiment. I mailed you a letter Saturday morning and stated to you that we were to go on a reconnoissance. We started at 8 o’clock and after marching 2 miles, came to the Rapidan. We did not cross for about an hour, and finally our Division—the Third—were ordered to ford the river, which was four feet deep. Oh, how cold it was! Then before we got to the top of the bank, we had to go about ten feet in mud 2 feet deep. Oh, it was dreadful. But this was but the commencement.

We had just crossed the river, and then had to run about a half mile up a steep hill to get out of the range of the enemy’s guns as they could shell us easy where they were. As it was, they threw a few shells into us, killing a few men. One of the shells hit one man in the centre of the body, cut him in two, threw his head, one leg, and his gun 30 feet in the air. Well, we got by there, and after going another half mile, stopped at the foot of a high hill. Right ahead of us, about a half mile, were the enemy heavily entrenched, and between them and us, at the top of the hill, were 3 large houses all together—in fact, a large Southern plantation. 1

We lay there all the rest of the day, and as near as I can learn, we were going to retreat again across the river, as soon as it became dark. But about 5 o’clock, while we were busily getting our coffee, the enemy threw a few shells right into our midst and immediately sent out skirmishers. We did the same, but they drove them back, and just at dusk, they sent out two Brigades to drive us back and take us prisoners. Our General immediately sent out the 39th New York, but after they had got to the top of the hill, the rebels fired a charge into them and they—like a pack of fools—broke and run. Upon this, the Gen. came down to our Brigade commander in an awful rage and says, “General, for God’s sake, give me the 14th Regiment up here. They wont run!”

So Col. Moore, started us off. We got as far up as the houses, but within 300 years of the houses on the right hand side, when the order was given to take those houses at any cost, oh! how the old 14th charged. Then those houses were full of rebels and the enemy were 6 to l of us, but forward was the word, and we went ahead, the enemy firing their bullets into us like hail. Dozens by dozens fell on our side, and when we came within about 40 feet of the houses, we had but three captains, and 30 or 40 men with us. But we kept on, and finally went into one of the houses. About the same number of rebels were there, but they would not surrender, and neither would we, and then we had a hand to hand fight. But finally the rebels run off, and by this time the 1st Brigade relieved us, and we went to work carrying off our dead and wounded.

Now for our loss in that terrible hour’s work. Oh, Ellen we have lost dreadfully. Our major is wounded. Two captains have each lost a part of their hand, one Captain had a ball shot through his foot, our fine Capt. Fred B. Doten is a prisoner in their hands, two lieutenants are wounded, and as for enlisted men, non-commissioned officers, and privates over one hundred and forty are either killed, wounded and missing. Just think of it, dear Nellie. We went into the fight with 350, and we have come out with just over half the number. Every company has lost one or more sergeants, and our company has lost my chum and bed fellow, Sergeant Myers. He was shot through the side, and probably died on the field. He was a noble soldier and the tears start when I think of his poor family. Co. I lost four sergeants, Co. C three, 2 Co. F two, and so [on] through all the companies.

But there is no use in enumerating our loss. It is over and we are back to camp—a little band of broken-hearted men. I am now alone in my tent, both of my tent mates being shot. Charles Scovill, Corp. is wounded and gone to Washington. Oh, it is lonesome, lonesome, and no mistake and I am broken-hearted.

Why I was not shot is a mystery to me, but it is the goodness of God. One bullet came along and hit me on the left foot, but its force had been spent and did me no damage, although my foot aches once in a while. We have lost in our company 12 men and our captain. But I have got to write to the friends of some of the boys who are wounded and must stop. I will write again soon. I feel bad though that it don’t seem as i f I could write a line. I could go to bed and cry like a child all day if it might do any good. I am well as can be expected, although I have got a bad cold. But do not worry for I shall be well soon. I will write again soon. Please let Lucy read this. Thank God I am well. Goodbye. From — Edward

1 See Morton’s Ford, Then & Now: The amazing Alfred Waud, on John Banks’ Civil War Blog. See also In the Footsteps of the 14th Connecticut Infantry by Frank Niederwerfer.

2 See story of Sgt. Alexander McNeil of Co. C, 14th Connecticut Vols.