The following letter was written by 72 year-old Joseph Long (1789-1864) of Newtown Stephensburg, Frederick county, Virginia. Joseph’s parents were Ellis Long, Sr. (1758-1837) and Elizabeth Pendleton (1761-1844). Joseph was married to Elizabeth Wilson (1791-1862) and the couple had several children, one of whom—Robert Henning Long (1832-1909)—is mentioned in the letter.

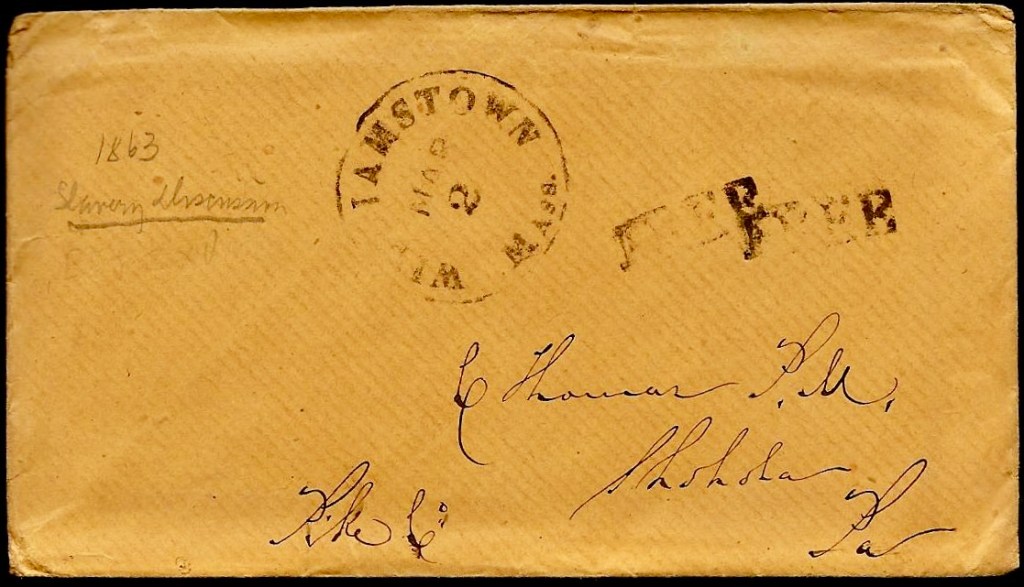

Joseph’s letter provides a summary of the violations of the South’s constitutional rights that culminated in the dissolution of the Union in 1861. It is evident that Joseph predominantly attributes responsibility to northern abolitionists and their relentless opposition to slavery. The letter was composed shortly after the assault on Fort Sumter and the passage of Virginia’s Ordinance of Secession. The identity of Joseph’s nephew, to whom the letter was addressed, is not revealed in the letter but it’s clear that he lived in the North. It would not be long before mail service between the two sections would be suspended.

[This letter is from the collection of Greg Herr and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

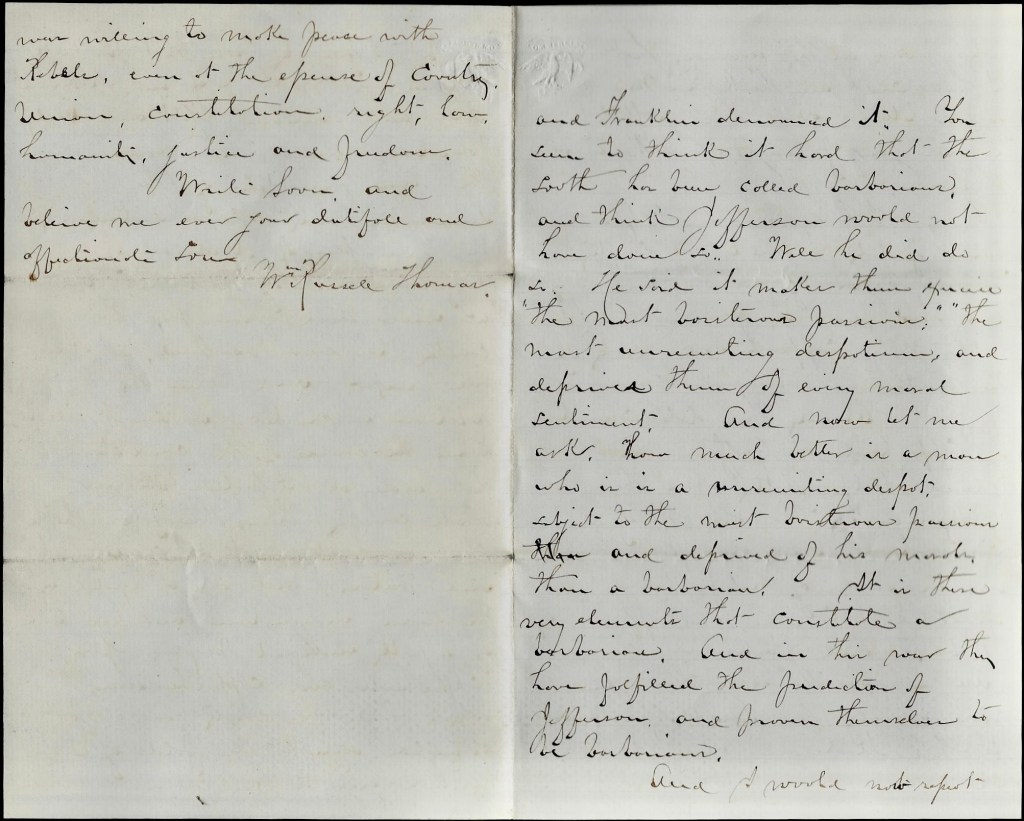

Transcription

Newtown Stephensburg [Frederick, Va.]

April 27th 1861

My dear Nephew,

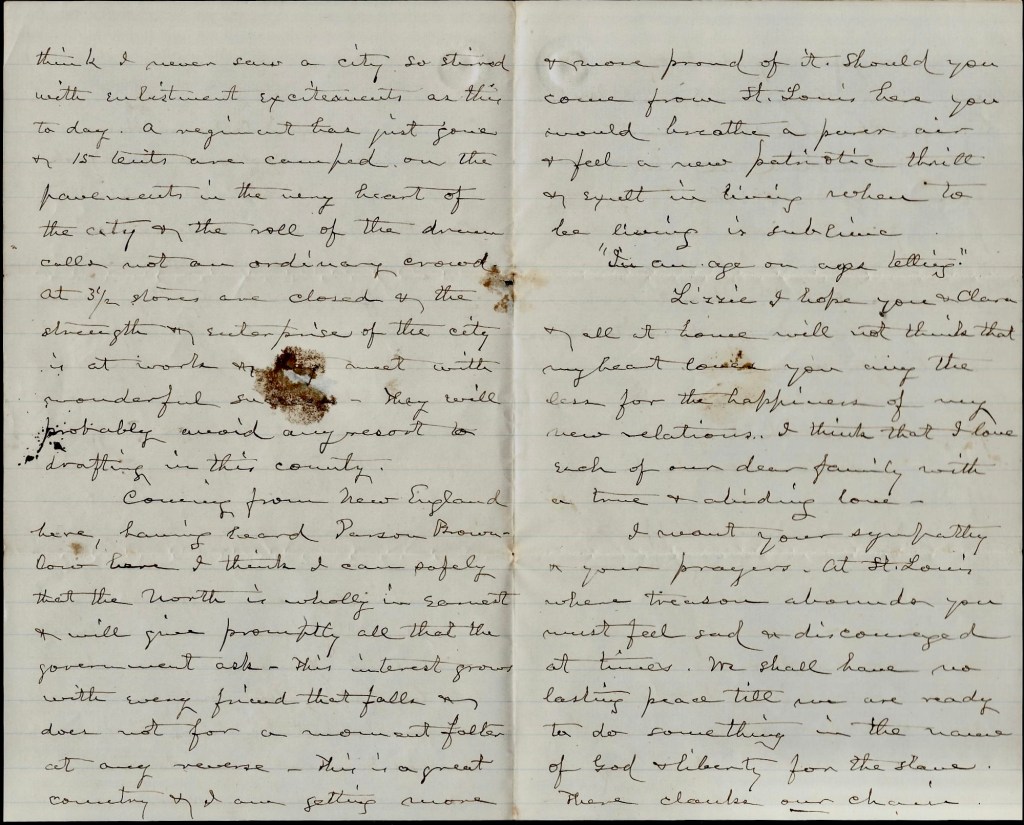

Yours of the 22nd was duly received. I feel much obliged to you for writing to me for the first time, and I hope it will not be the last as it is always gratifying to me to hear from you all. I seldom hear from you and when I did, it was through my friends—the Steele family. I am sorry you did not mention your brothers & sisters & their families as I should have been much pleased to hear from you all and how you are all getting along in life. Myself and family are in usual health. Your cousin Robert H. Long is now in the Southern army stationed at Harper’s Ferry. He is second in command of a troop of cavalry 1 and has left a wife and three children, all to defend what we consider our constitutional right, as handed down to us by the Revolutionary Fathers.

The South has been imposed upon steadily by the North for the last thirty years and they have been blowing the fuel of Abolitionism until it has kindled a deadly flame which I greatly fear will result in the destruction of our once happy Union for your miserable northern abolition President seems determined to destroy as much of the public property as he possibly can. He commenced by ordering the destruction of Fort Moultrie which caused the South Carolinas to fortify and take Fort Sumter. He next ordered the destruction of Harpers Ferry. His troops succeeded in destroying an immense quantity of arms of every description of the most improved quality which caused the Governor of our State to have the place guarded by a sufficient number of troops, and all the machinery that was not injured by the blowing up and burning of the works, is now removing. to Richmond which will require 10 of our large wagons six months in transporting it. And not content with that, he has caused the destruction of the Navy Yard at Portsmouth, Va., and much valuable property estimated at ten millions dollars, causing to be burnt to the water’s edge six or seven of our most valuable war vessels, and it is thought he will destroy all the forts and public works in the State of Virginia relied on.

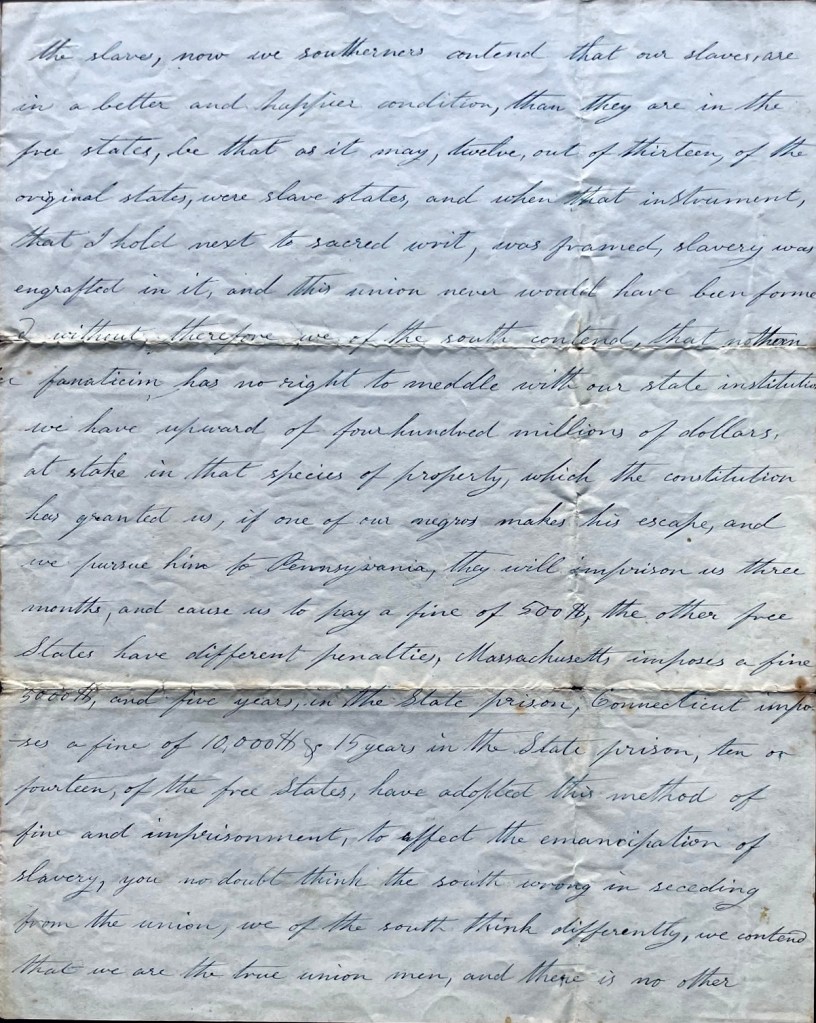

Whilst our conventions were endeavoring to bring about a compromise, he was filling the different fortifications with abolition troops who are determined to destroy the country or, as they say, to liberate the slaves. Now we southerners contend that our slaves are in a better and happier condition that they are in the free states. Be that as it may, twelve out of thirteen of the original states were slave states, and when that instrument that I hold next to sacred writ was framed, slavery was engrafted in it, and this Union never would have been formed without. Therefore, we of the South contend that northern fanaticism has no right to meddle with our state institution. We have upward of four hundred millions of dollars at stake in that species of property which the constitution has granted us. If one of our negroes makes his escape and we pursue him to Pennsylvania, they will imprison us three months and cause us to pay a fine of $500. The other free states have different penalties. Massachusetts imposes a fine of $5,000 and five years in the State Prison.

Ten or fourteen of the free states have adopted this method of fine and imprisonment to effect the emancipation of slavery. You no doubt think the South wrong in seceding from the Union. We of the South think differently. We contend that we are the true Union men and there is no other remedy left us of securing our property. We have held out compromises which they have treated with contempt, and as to the Capitol, it stands on southern soil and it is as dear to southerners—and I believe much more so—than to northern abolitionists. The South has only contended for her constitutional rights and wish nothing more.

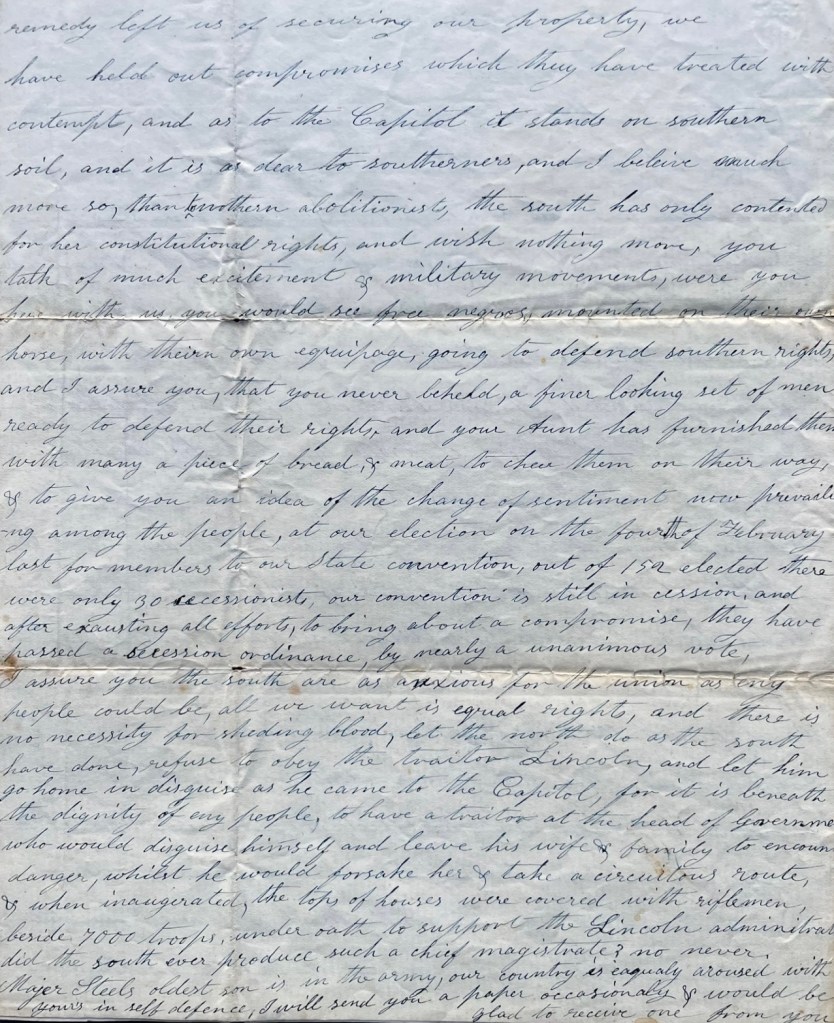

You talk of much excitement & military movements. Were you here with us, you would see free negroes mounted on their own horse with their own equipage going to defend southern rights and I assure you that you never beheld a finer looking set of men ready to defend their rights, and your Aunt has furnished them with many a piece of bread & meat to cheer them on their way. And to give you an idea of the change of sentiment now prevailing among the people, at our election on the fourth of February last for members to our State Convention, out of the 152 elected, there were only 30 secessionists. Our convention is still in session and after exhausting all efforts to bring about a compromise, they have passed a secession ordinance by nearly a unanimous vote. I assure you, the South are as anxious for the Union as any people could be.

All we want is equal rights and there is no necessity for shedding blood. Let the North do as the South have done—refuse to obey the traitor Lincoln, and let him go home in disguise as he came to the Capitol, for it is beneath the dignity of any people to have a traitor at the head of Government who would disguise himself and leave his wife & family to encounter danger, whist he would forsake her & take a circuitous route, & when inaugurated, the tops of houses were covered with riflemen, beside 7,000 troops under oath to support the Lincoln administration. Did the South ever produce such a chief magistrate? No, never.

Major Steele’s oldest son is in the army. Our country is equally aroused with yours in self defense. I will send you a paper occasionally & would be glad to receive one from you. Your Uncle John & Mr. Steele desire to be remembered to you. Their families are in usual health. Gen. Harney was captured at Harpers Ferry 25th at 2 a.m. on his way to Washington & taken to Richmond. 2 Your affectionate Uncle, — Joseph Long

1 Robert H. Long served in Co. A, 1st Virginia Cavalry. He enlisted 19 April 1861.

2 In April 1861, he was ordered to report to Washington by Lincoln’s new Secretary of War, Simon Cameron. The train on which he was traveling was stopped at Harper’s Ferry, and a young confederate office boarded announcing “General Harney, sir, you are my prisoner!” He was told a Confederate battalion had surrounded the train, sent with orders to intercept him before he reached Washington. In this way, William S. Harney became the first prisoner taken by the South in the Civil War. Later, in Virginia, William received apologies for the manner in which he was brought there, and he was offered a Confederate command under Robert E. Lee. He had previously served with Lee in the U.S. Army in the Mexican War. William refused, and he was allowed to continue on his trip to Washington. [Military Career of William Selby Harney]