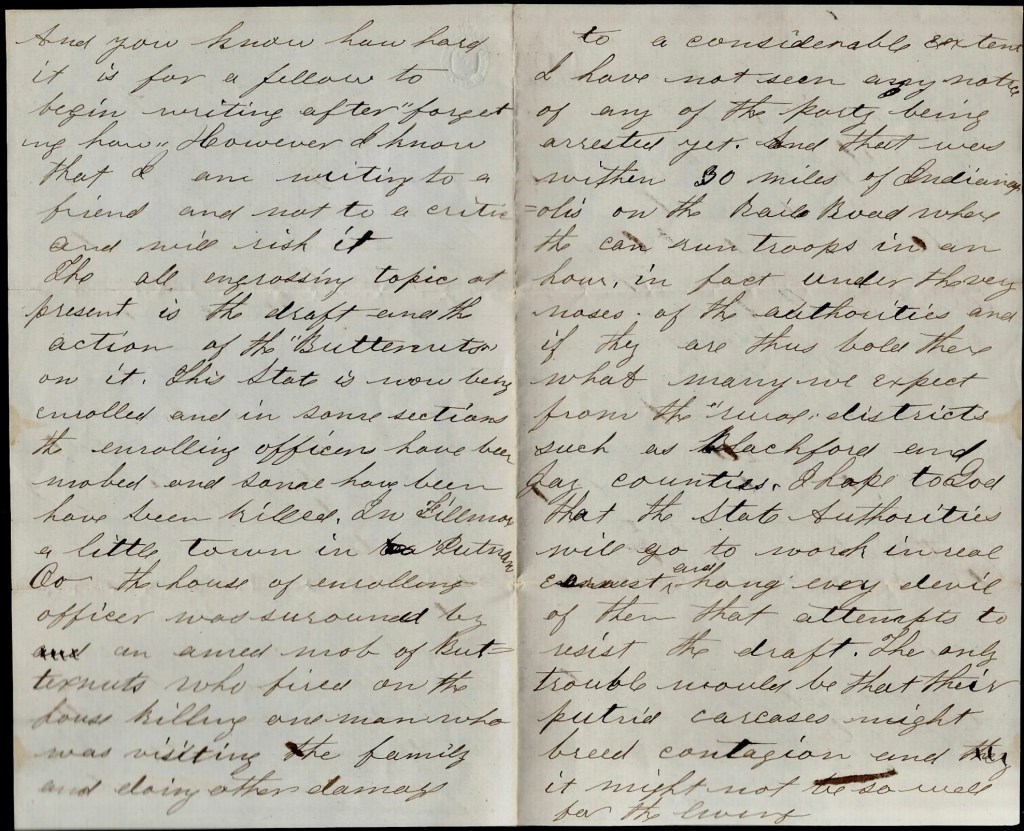

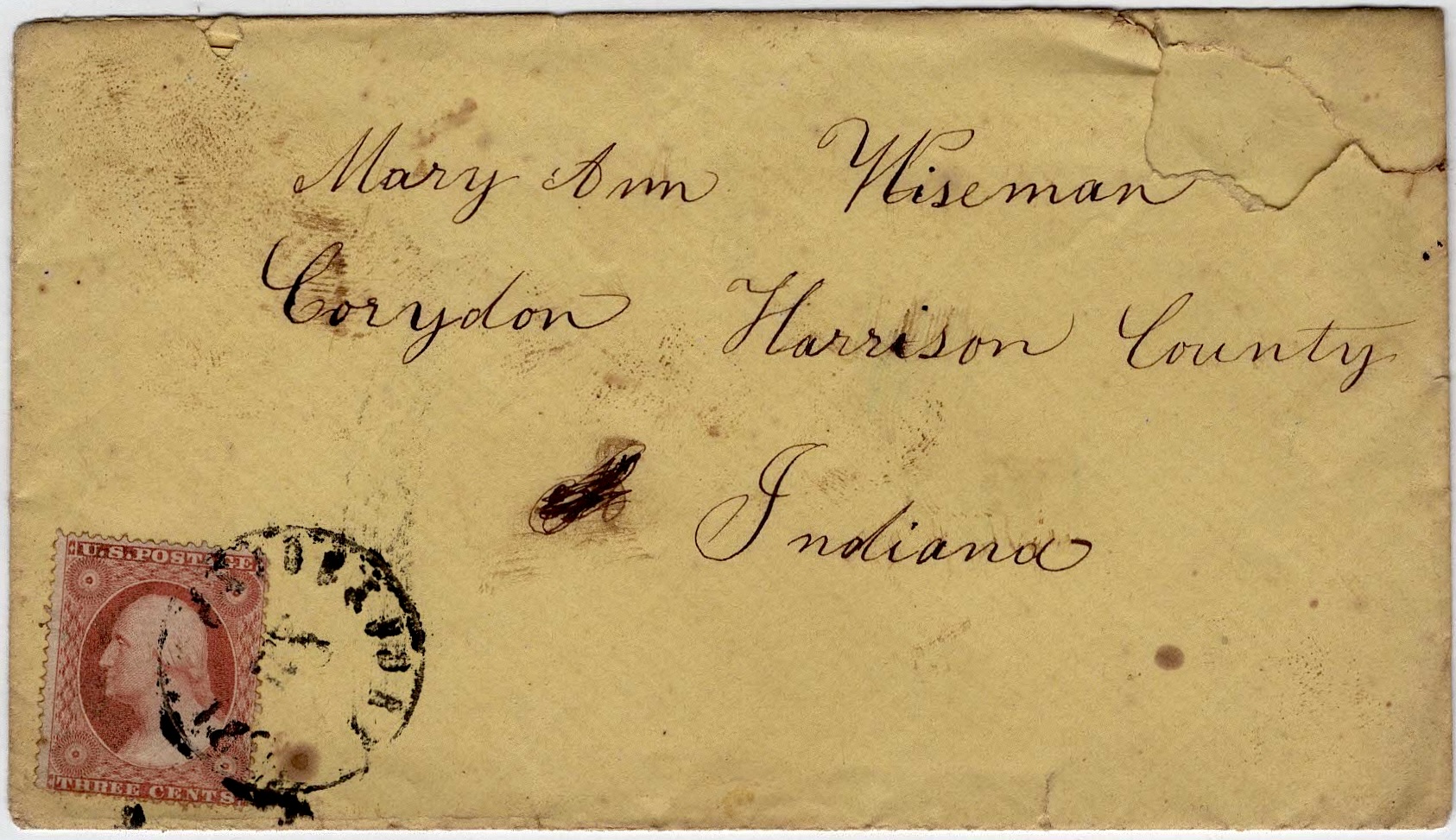

The following letter was written by Rachel (Hawkins) Epperson (1827-1896), the wife of William Epperson (1833-1904) of Decatur, Marion county, Indiana. At the time she wrote this letter in October 1864, she was the mother of two children—Austin L. Epperson (1856-1931) and Uriah Spray Epperson (1861-1944). She was also pregnant with her third child, Emma Epperson (1865-1944).

Rachel and her husband were Quakers. She was the daughter of Nathan Hawkins and Rebecca Roberds. She was married first in Bucks county, Pennsylvania, April 1848, to Joseph Furnas (1826-1849) but he died the following year. As the letter will show, Rachel’s 2nd husband, William Epperson, was in the meat business. Af few years after this letter was written, the family moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where William pioneered the Pork and Beef Packing industry in 1868.

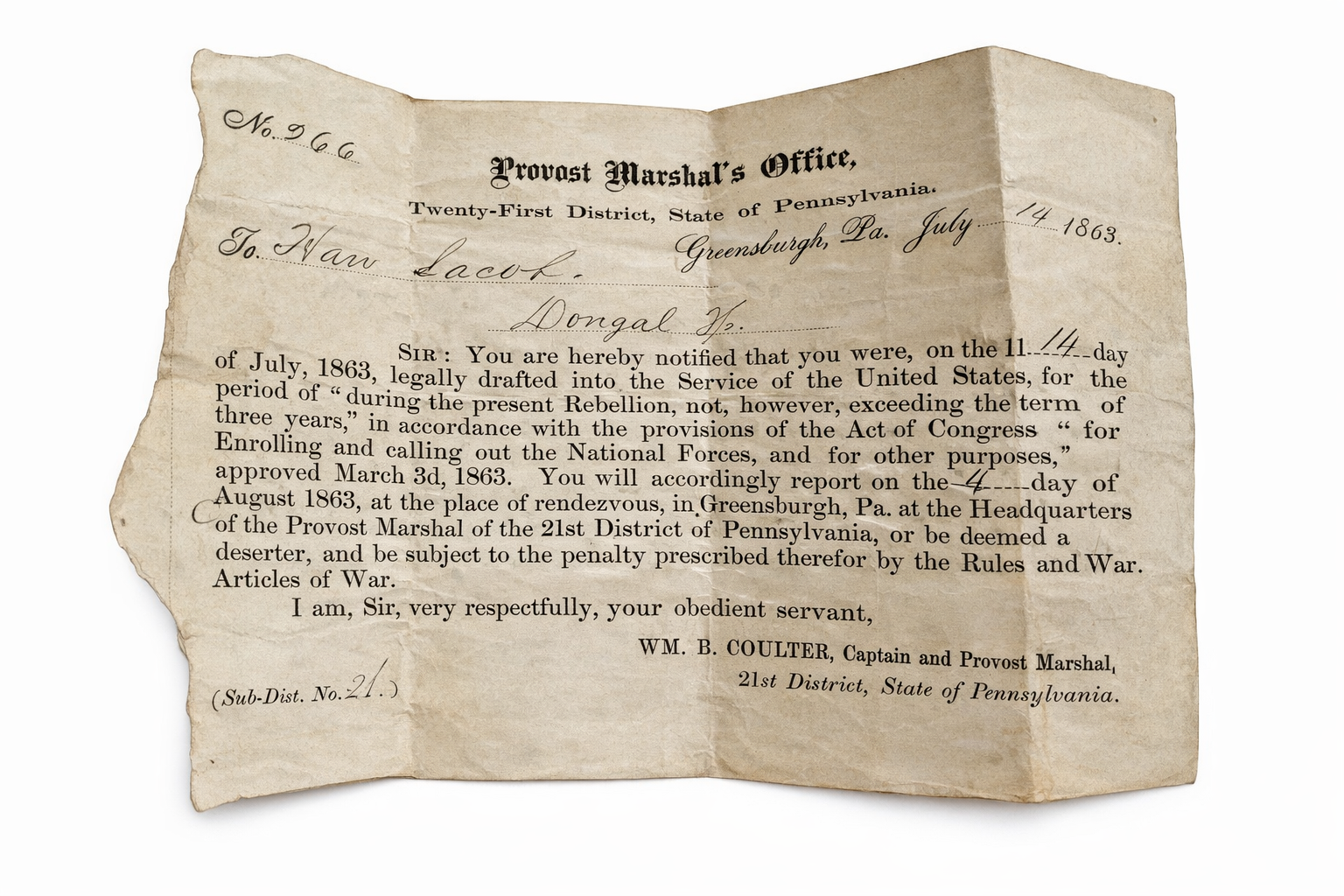

Rachel wrote the letter to her “respected friend” Mary Ann (Byerly) Wiseman (1837-1922) who was married to William Benjamin Wiseman (1832-1909) of Corydon, Harrison county, Indiana, in 1858. Mary Ann was the daughter of Jacob Byerly (1812-1862) and Susan Eliza Wiseman (1817-1869).

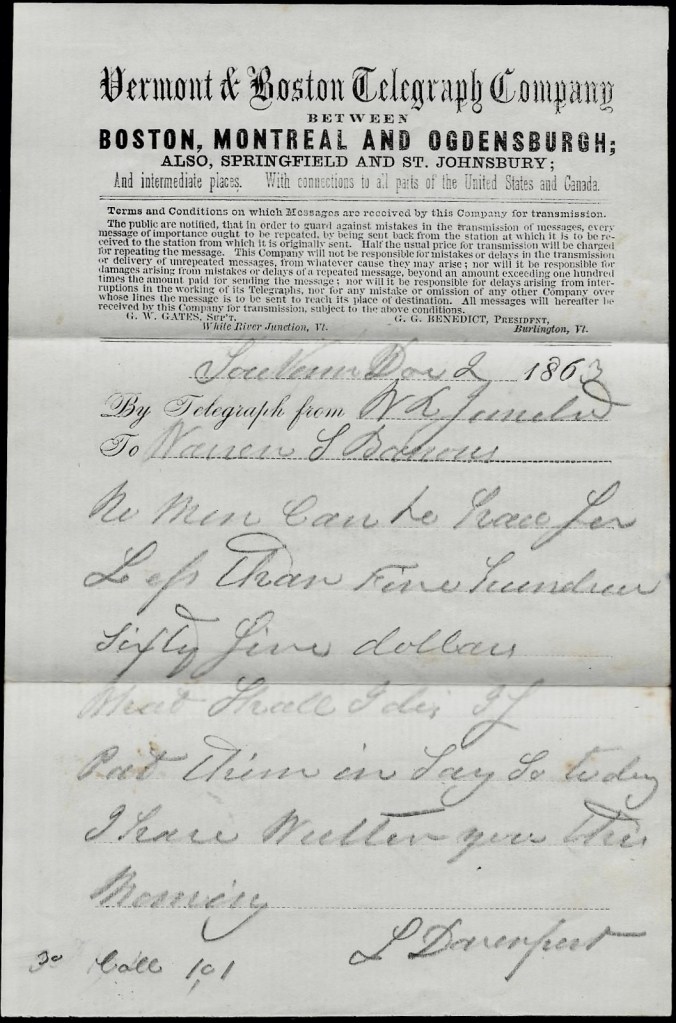

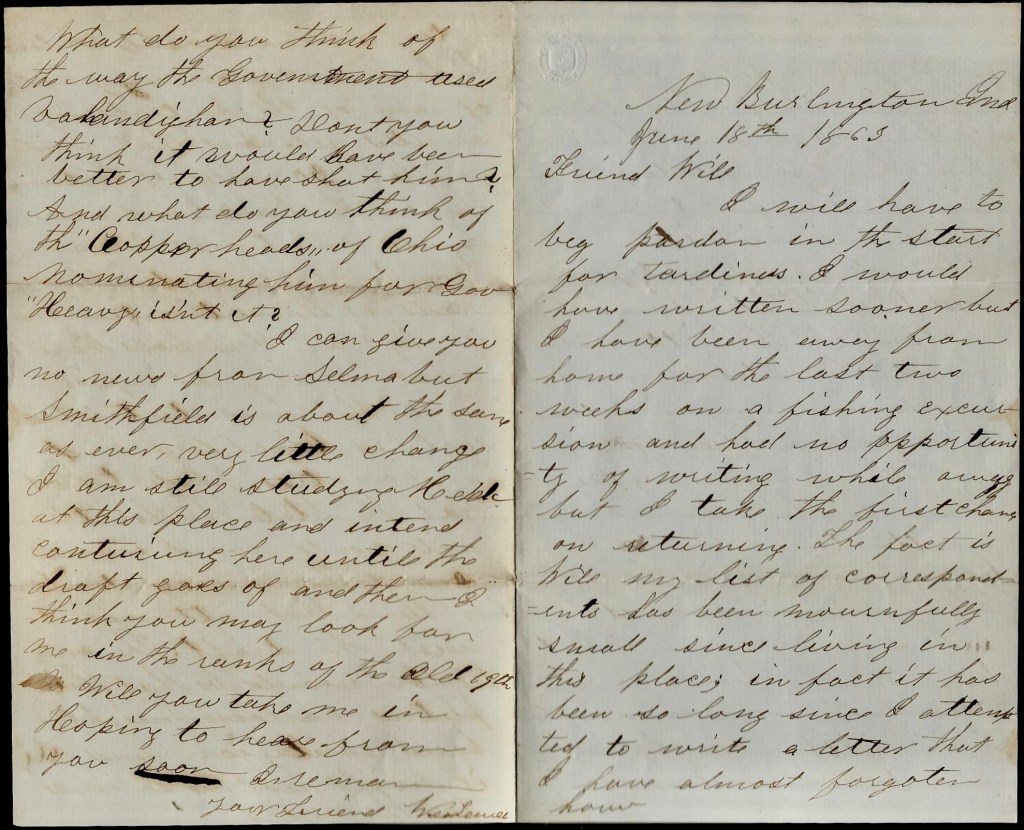

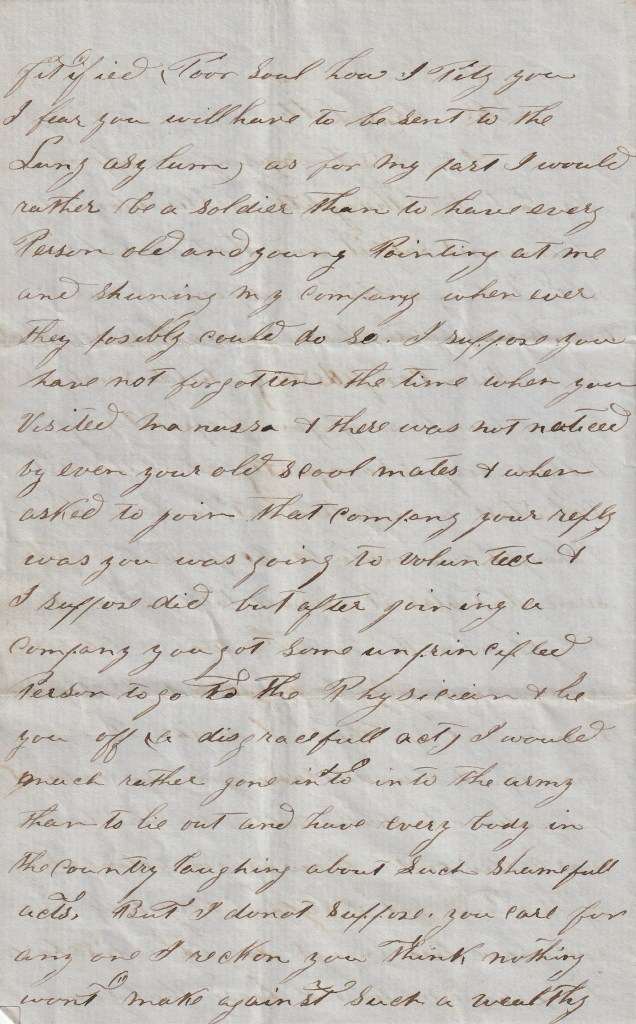

The letter speaks of the military draft in Indiana in 1864 and the effects it was having in disrupting the lives of her neighbors as well as her own family. In 1864, Indiana, like other Union states, held multiple drafts to meet federal quotas, allowing draftees to avoid service by hiring a substitute or, early in 1864, paying a $300 commutation fee. Substitutes were often paid high fees (sometimes over $1,000) by wealthy men, and they were frequently sourced from men under 20, non-citizens, or previously exempt individuals.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

10th Month, 30th, 1864

Respected Friend,

I take up my pen to inform thee of sorrowful news—viz: Lewis [Wiseman] 1 was drafted, and not being able to buy a substitute, he had to go into camp and was there a few days, and I hear they have left town and gone to Nashville (he has left Eliza in her usual condition and the time is not far distant). Philip went as a substitute for some man. John Hawkins is also gone. There was but few escaped the draft through here. Amongst the rest was William but the Quakers got off by paying three hundred dollars. Fred France went. It was hurting him very much.

Our healths are pretty good and I hope thee is quite well. I wish to hear from thee very much. Joel is here and well. He escaped the draft. Isaac Hawkins’s mother-in-law is not living—not much complaint in the neighborhood. William is not at home much. He bought hogs and took to Illinois and bought corn there and is feeding them there. He has a share of fourteen hundred head. He also bought 400 head of cattle out there and has sold them at Indianapolis and has had 140 head drove through to Indianapolis, and Jesse Merary, Sam Redman, David Compton, and William Whitson, is now on the road to Indianapolis with another drove. Then William will car the balance. He expects to feed 100 head out there this winter. The time seems very long to me when he is gone so much but I try to bear it patiently for the sake of trying to get out of debt. But this draft has sunk him 300 dollars more. He paid 7 dollars a hundred for hogs to fatten (pretty steep that).

We have had a literary at our school house all summer and the winter school commences in the morning for four months. Eliza Allen is to be teacher. She wants to board at [ ‘s] but they don’t talk like boarding her. Huldah Furnas 2 has been gone to Columbus water cure 3 for several weeks but is to come home tomorrow. Her Father is dangerously sick and they have sent for her.

William’s mother has rented out her house and lot and packed her things up, some one place and some another, and talks like she was a going to live amongst her children. [Rev.] Ephraim Bowles 4 has rented a place in Illinois and talks of moving there this winter. He is doing about as usual, eating and wearing and that is about all he makes, but he makes as big calculations as ever.

According to my own wishes and Joel’s request, I have written this. He said if I would write, he would pay the postage. Please write and not wait as I have done. — Rachel

to Mary Ann

1 Lewis Wiseman of Decatur, Marion county, Indiana, was drafted and placed in the 29th Indiana Infantry.

2 Huldah (Jessup) Furnas (b. 1834) was the daughter of Alfred Jessup (1810-1865) and Betsy Jessup (1814-1864) of Hendricks county, Indiana. Huldah was the wife John W. Furnace (1835-1899) of Marion county, Indiana.

3 Dr. Shepard’s Water Cure Establishment in Columbus, Ohio, was a prominent 19th-century hydropathic facility located in the vicinity of what became known as Shepard Station. Established in 1853, it specialized in treating chronic and nervous diseases, particularly in women, using water-based therapies like wet sheet packs and baths.

4 Rev. Ephraim Bowles (1829-1914) was enumerated in Decatur, Marion county, Indiana in the 1860 US Census. In 1870, he was enumerated in Penn, Guthrie county, Iowa. Living next door to Ephraim in 1860 was 32 year-old Lewis Wiseman and his 30 year-old wife Eliza with a brood of children born every other year.