Not unlike the poisonous effects of the shadow of the deadly upas tree,” secession “has spread a blight and desolation over the country.” So wrote 42 year-old Benjamin D. Carpenter (1819-1895), “a northern man who settled in Alexandria county, Virginia, long before the war, having a large farm at Red Hill…Coming to Washington during the war, he bought a large farm on Rock creek west of Brightwood, where he lived for nearly a quarter of a century. This place is now embraced in Rock Creek Park.” [Source: Obituary] Benjamin was married in the mid 1840s to Anna Maria Crocker (1822-1895) and was the proud father of four daughters.

Benjamin was trained as a surveyor and he was the first to prepare a map showing the metes and bounds of the District of Columbia.

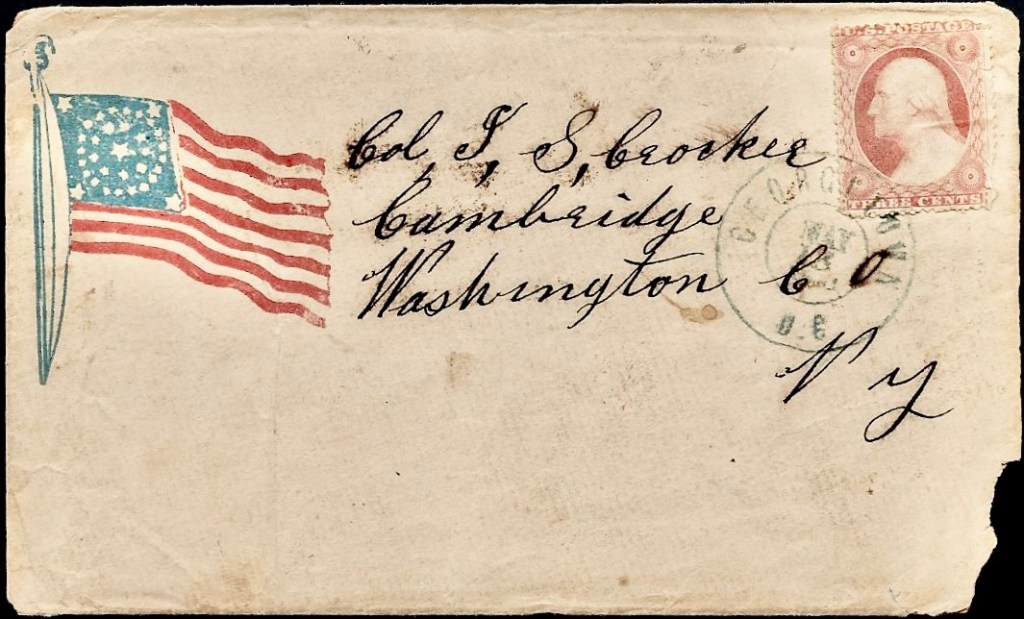

Benjamin wrote the letter to his brother-in-law, John Simpson Crocker (1825-1890) who was appointed Colonel of the 93rd New York Infantry. He was captured during the siege of Yorktown and imprisoned at Libby Prison and later Salisbury before being exchanged in August 1862.

Transcription

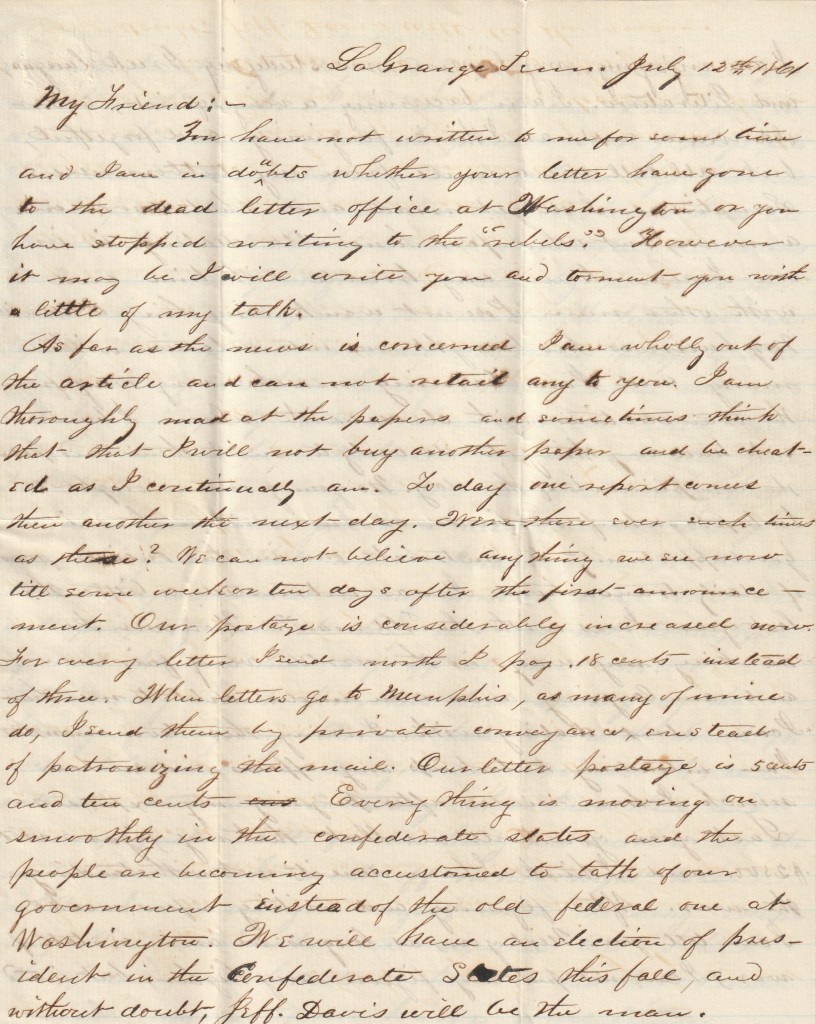

Fairfax county [Va.]

May 30th 1861

Dear brother,

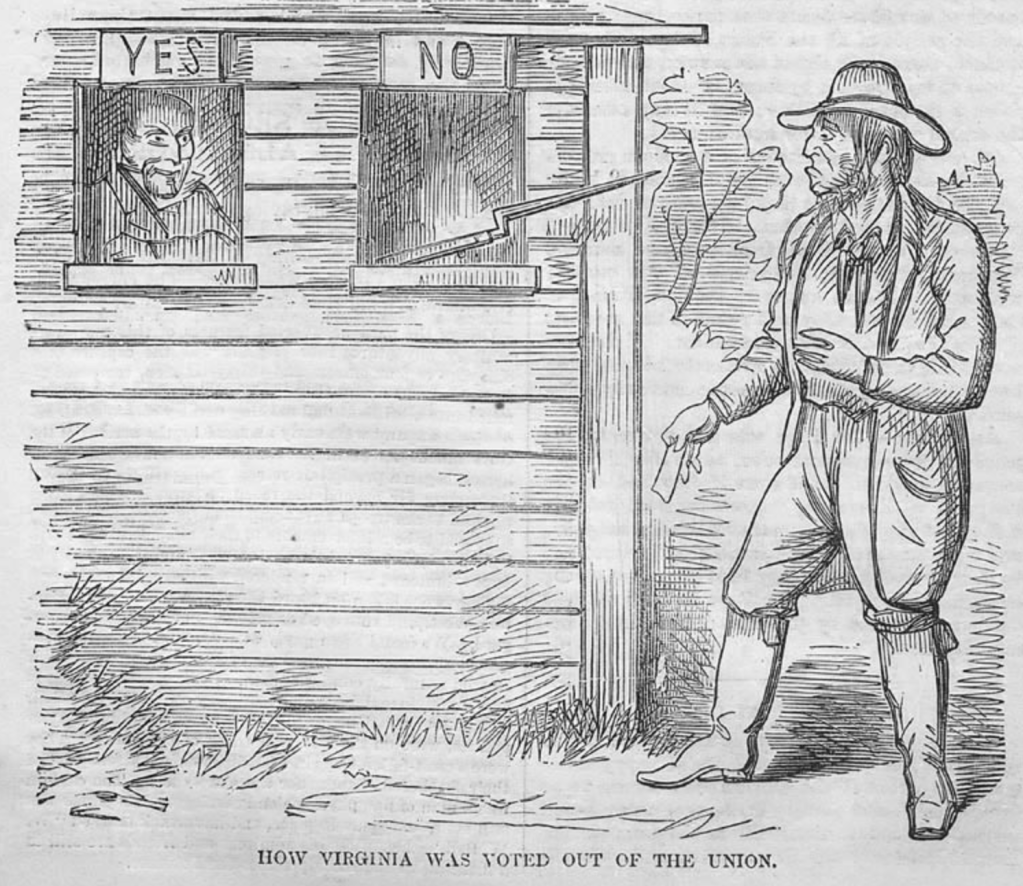

Yours has been duly received and I hasten to reply. You will perceive that I have changed front or right about faced since I last wrote you. That’s so. I go in for the motto that heads this sheet secession is but a name for all that is devilish and infernal. If you or anyone else were here only one week, you would see a fair illustration of Mexican despotism. You would see the most intense hatred of those anti-white labor Nero’s that would cause your blood to boil with indignation and would make you turn away from them with loathing and contempt. Men are prosecuted and threatened with violence and even with hanging for wishing to cling to that government which has protected them in their civil and religious liberty, which has thrown over them and around them a halo of Freedom and prosperity that no other government under heaven has. Men are fleeing for their lives for wishing to preserve the Union of these states which was formed for the protection of our lives, liberty and property.

Secession leaders marched about breathing vengeance on all who would not enroll themselves with them under the black banner of Treason whose baneful shadow is not unlike the poisonous effects of the shadow of the deadly upas tree. It has spread a blight and desolation over the country; it has paralyzed and prostrated business and the energy of the people; it has destroyed the confidence between friends and neighbors; it has made vacant firesides and empty houses; it has made silent workshops and deserted villages; it has silenced the ploughman’s song and the wagons rattle on the roads, and last but not least of all, it seeks to pull down the strong pillars of the wisest and best governments, and if they can accomplish no more, involve all in one common total overthrow. It makes my heart bleed to see the people leaving for life, fleeing from that demon of secession which would wring the last drop of blood from one’s heart for wishing to live in the Union—the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Thirty-four families left Vienna in two days with what they could hastily gather up and then bid adieu to their homes for which they have toiled to make comfortable and pleasant. John, a great gloom is over the land like some great and sudden calamity. The sun seems to shine through some kind of a veil which casts a shade of sadness over heavens and earth, not unlike the feeling of some swift and sudden calamity about to happen, that strikes terror and dread to the heart. Men were deprived of the elective franchise through fear and suffer all the horror of a reign of terror rather than vote at all.

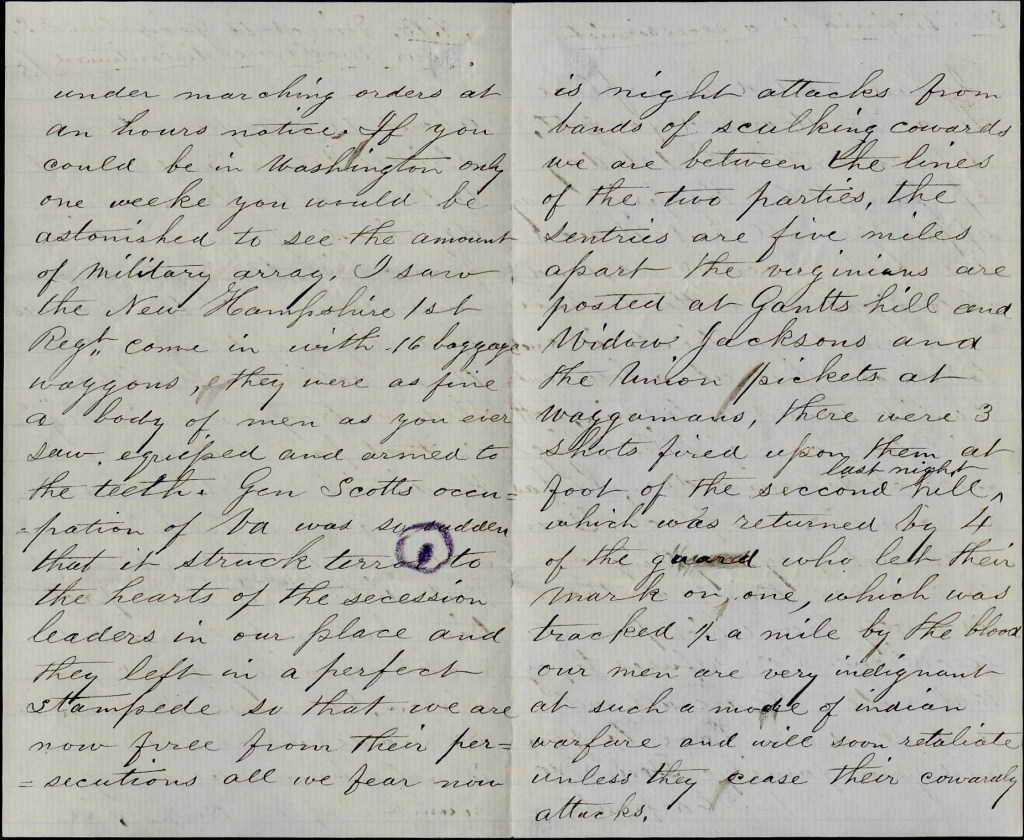

The Federal troops are in Virginia in that part that once was the district which makes them about four miles from us and even their shadow at that distance is some protection but not enough to make us entirely free from alarm. A move is soon to be made—where and when is not known—as a large number of troops are under marching orders at an hour’s notice. If you could be in Washington only one week, you would be astonished to see the amount of military array. I saw the New Hampshire 1st Regiment come in with 16 baggage wagons. They were as fine a body of men as you ever saw, equipped and armed to the teeth. Gen. Scott’s occupation of Virginia was so sudden that it struck terror to the hearts of the secession leaders in our place and they left in a perfect stampede so that we are now free from their persecutions. All we fear now is night attacks from bands of skulling cowards. We are between the lines of the two parties, The entries are five miles apart. The Virginians are posted at Gantt’s Hill and Widow Jackson’s, and the Union pickets at Waggaman’s. There were three shots fired upon them at the foot of the second hill last night which was returned by four of the guard who left their mark on one, which was tracked half a mile by the blood. Our men are very indignant at such a mode of indian warfare and will soon retaliate unless they cease their cowardly attacks.

I have rented your place to a Dr. Harrold for $50 dollars until the 1st day of January 1862. The price may appear small but it was the best I could do adn I thought it better to have someone to cultivate it and take care of it at a low rent than it should go to ruin. Lott will take care of Will’s things. subject to your order. He has the cows on his place. You need not pay anything on your place this year. There is a stay law which prevents executions. Dorr refuses to pay that note. We are all well and send our love to you and your families. Yours, &c. — B. D. Carpenter

Ellen Virginia is a secessionist.

N. B. Direct to Georgetown. Our mails are discontinued.