The following letter was written by Rogena Almira Scott (1840-1869), the daughter of Madison Scott (1813-1851) and Hanna Landress Beach (1817-1872) of Franklin, Vermont. Genie and Rev. John G. Bailey were married on 17 February 1863 in Warner, New Hampshire, but she only lived until 1869. The Scott Family Record states that Rogena “finished her education at Ohnson Academy, Vermont, and devoted several years to teaching in the South. She was a lady of fine accomplishments.” Genie’s younger brother, Don Eugene Scott (1844-1923) served in the Civil War as a private in Co. E, 9th New Hampshire Infantry; later in Co. D, 11th New Hampshire Infantry.

We learn from this letter that 21 year-old Genie was teaching at the Southside Institute—a school for girls—in Nashville, Tennessee, when the Civil War erupted in 1861. The principal of the school was 41 year-old Mrs. Emma Holcombe. The school was operated in the 24-room mansion of Col. A. W. Putnam opposite the Capitol Building. The letter was addressed to her mother in Warner, New Hampshire, now married to her second husband, Rev. Daniel Warner—a Congregational clergyman. She writes of the recent fall of Nashville to the Union army. “I can hardly sit still to write this letter, but feel much more like dancing about the room like a child three years old or a crazy person,” she confessed to her mother, with whom all correspondence had been cut off six months previously.

She also gives us a stirring description of the panic by the citizens of Nashville following the receipt of news that Fort Donaldson had been taken by Grant’s army. “Men and women rushed out into the streets wringing their hands and crying, everybody seemed bewildered and not to know what to do, asked all sorts of incoherent questions and received just as incoherent replies.”

In researching the Southside Institute, I discovered that it was the 1861 graduating class of young women who made and presented the Confederate flag that flew over the State Capitol—perhaps the same flag that was lowered when Union troops took possession of the town.

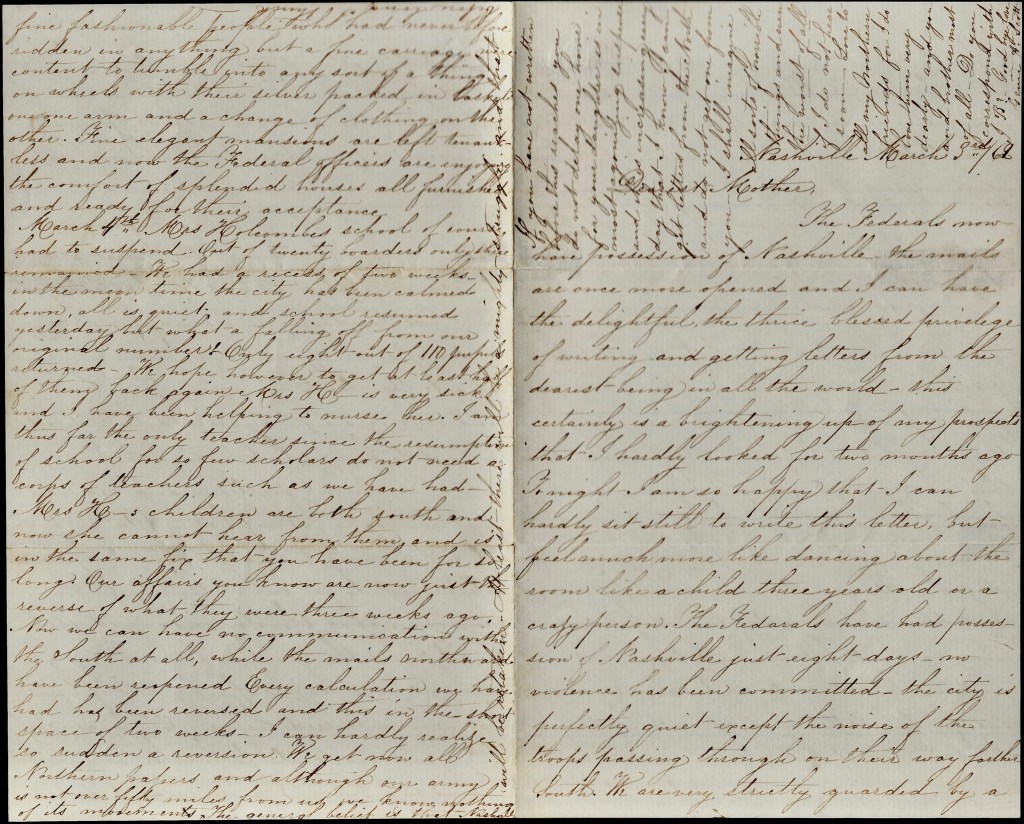

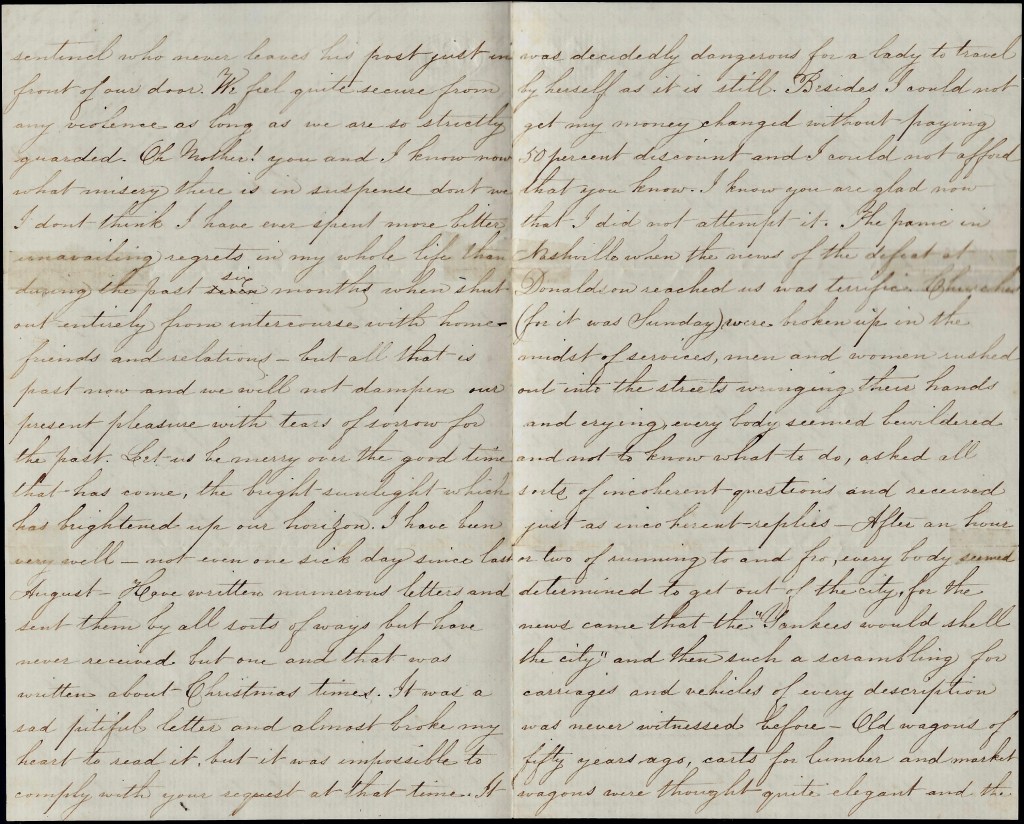

Transcription

Nashville [Tennessee]

March 3rd, 1862

Dearest Mother,

The Federals now have possession of Nashville. The mails are once more opened and I can have the delightful, the thrice blessed privilege of writing and getting letters from the dearest being in all the world—this certainly is a brightening up of my prospects that I hardly looked for two months ago. Tonight I am so happy that I can hardly sit still to write this letter, but feel much more like dancing about the room like a child three years old or a crazy person.

The Federals have had possession of Nashville just eight days. No violence has been committed. The city is perfectly quiet except the noise of the troops passing through on their way farther South. We are very strictly guarded by a sentinel who never leaves his post just in front of our door. We feel quite secure from any violence as long as we are so strictly guarded. Oh Mother! you and I know now what misery there is in suspense, don’t we. I don’t think I have ever spent more bitter unavailing regrets in my whole life than during the past six months when shut out entirely from intercourse with home, friends, and relations. But all that is past now and we will not dampen our present pleasure with tears of sorrow for the past. Let us be merry over the good time that has come—the bright sunlight which has brightened up our horizon.

I have been very well—not even one sick day since last August. Have written numerous letters and sent them by all sorts of ways but have never received but one and that was written about Christmas times. It was a sad pitiful letter and almost broke my heart to read it, but it was impossible to comply with your request at that time. It was decidedly dangerous for a lady to travel by herself as it is still. Besides, I could not get my money changed without paying 50 percent discount and I could not afford that you know. I know you are glad now that I did not attempt it.

The panic in Nashville when the news of the defeat at [Fort] Donaldson reached us was terrific. Churches (for it was Sunday) were broken up in the midst of services, men and women rushed out into the streets wringing their hands and crying, everybody seemed bewildered and not to know what to do, asked all sorts of incoherent questions and received just as incoherent replies. After an hour or two or running to and fro, everybody seemed determined to get out of the city for the news came that the “Yankees would shell the city” and then such a scrambling for carriages and vehicles of every description was never witnessed before. Old wagons of fifty years ago, carts for lumber and market wagons were thought quite elegant and the fine fashionable people who had never before ridden in anything but a fine carriage were content to tumble into any sort of a thing on wheels with their silver packed in baskets on one arm and a change of clothing on the other. Fine elegant mansions are left tenantless and now the Federal officers are enjoying the comfort of splendid houses all furnished and ready for their acceptance.

March 4th. Mrs. [Emma] Holcombe’s school of course had to suspend. Out of twenty boarders, only three remained. We had a recess of two weeks. In the meantime, the city has been calmed down. All is quiet, and the school resumed yesterday. But what a falling off from our original numbers! Only eight out of 110 pupils returned. We hope however to get at least half of them back again. Mrs. H. is very sick and I have been helping to nurse her. I am thus far the only teacher since the resumption of school for so few scholars do not need a corps of teachers such as we have had. Mrs. H.’s children are both south and now she cannot hear from them, and is in the same fix that you have been for so long. Our affairs you know are now just the reverse of what they were three weeks ago. Now we can have no communication with the South at all, while the mails northward have been reopened. Ever calculation we have had has been reversed and this in the short space of two weeks. I can hardly realize so sudden a reversion.

We get now all Northern papers and although our army is not over fifty miles from us, we know nothing of its movements. The general belief is that Nashville will be retaken. At least there will be a mighty struggle and that before long I think. If you have not written before this reaches you, do not delay one hour for your daughter is in most agonizing suspense and it is increasing everyday that I know I can get letters from the North and do not get one from you. I shall imagine all sorts of horrible things and even the worst of all if I do not hear soon. Love to all my Northern friends for I do love them very dearly and you and brother most of all. Goodbye. Love, Genie A. Scott