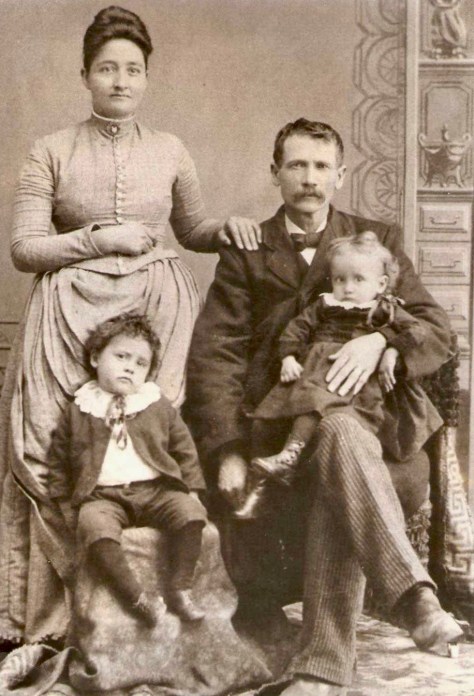

The following Civil War letters were written by Charles Pitman Atkinson (1832-, the son of shoemaker Samuel Clark Atkinson (1793-1884) and Naome Suydam (1800-Aft1860) of Lambertville, Hunterdon county, New Jersey. In 1850, 18 year-old Charles was enumerated in his parents home in Raritan where he was learning the printer’s trade. The 1900 Census informs us that Charles and Phebe Van Meter (1830-1918) married in 1850 and that their first child, Ruth, was born in May 1851. Their son, Charles Summerfield (“Summy”), was born in 1859. A third child, Frank, was born in 1866 after Charles returned home from the war.

Phebe was the daughter of David Van Metter (1784-1834) and Ruth Whitaker (1789-1864) of Pittsgrove, Salem county, New Jersey. Charles often expresses his willingness to serve in the Union army, believing it his “duty,” but he may have also been seeking relief from the critical eye and tongue of his mother-in-law with whom he apparently could never get along with. Her death is February 1864 made his return home all the more joyful, no doubt.

The letters frequently mention William (“Will”) B. Strom, a native South Carolinian who grew up on his father’s plantation in the Edgefield District, served briefly in Hampton’s Legion, and then defected and enrolled himself in the same company with Charles. Charles became fast friends with Will and it’s apparent that he and Phebe even attempted to orchestrate a marriage between Will and Phebe’s cousin, Amanda Van Meter (1836-1920)—the daughter of Enoch M. Van Meter (1810-1874) of Pittsgrove. Amanda never married, however.

Charles enlisted in Co. F, 3rd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery in October 1862. Those seeking to learn more about the regiment through Charles’ letter will be disappointed, however. Most of Charles’ time in the service was spent on detail, including serving as a hospital steward in the Post Hospital at Fortress Monroe and as an “Asst. Surgeon” aboard the Flag of Truce steamer New York.

Letter 1

Coopers Creek near Camden [New Jersey]

November 18th 1862

My dear Phebe,

I was very sorry to disappoint you on last Saturday but I could not avoid it. I felt very anxious to be with you and the children but I could not well do so for if I had of come, I should have to of come back on Monday morning. I have received part of my bounty and am to receive the balance today. I have got a pass to come home on next Saturday. I expect to stay a week or perhaps more. Mr. [William B.] Strom is coming with me. you can make preparations to receive us if you like. We will be there to eat supper with you. Mr. Strom is a young man that has been reared in luxury and wealth but with all that, he is very kind and gentlemanly. He was pressed into the rebel service in March last and has never been out of camp since. He is very anxious to get out for a few days. 1

My health keeps very good which fact makes me well satisfied to remain. I believe it will be for the best at present. I am promised an office in the hospital. If I get that, I shall not be exposed to danger from the bullets if we ever fore any, which I think is doubtful. I have been engaged in the hospital a good deal since I have been here. It will be a great advantage to me if I should ever practice medicine. The people are all very kind to me. After the regiment is fully organized, I shall get to come home oftener which is now being done.

Enclosed I send you five dollars so that you can get anything you may need in the house. I shall have to send this by mail. There are many things I could write to you. about but as I. am coming home so soon, I will close. Remaining your affectionate husband, — C. P. Atkinson

1 According to enlistment records, William B. Strom was born about 1840 in Wayne county, North Carolina, He gave his occupation as “merchant.” However, census and family genealogy records reveal that he was actually born in 1838 in the Edgefield county, South Carolina, his father being the planter Samuel C. Strom (1813-1870) and his mother Mary Ann Burton (1817-1914). William was attending medical school in Pennsylvania when the Civil War began. His obituary reports that “although his father was a Colonel in the Confederate army, young Strom enlisted in the service of the United States where he rendered efficient service during most of that great conflict. After the close of the war he entered the Georgia Medical College, where he graduated with high honor. He again entered the service of the government as army surgeon, in which capacity he served about fourteen years. After spending about one year in California, he came to Centropolis, Kansas where he married Miss Tillie X. Gants, who, with four children, survives him. He practiced medicine in Beloit, Kansas about two years when he moved to Melvern, Kansas, March 1888 where he practiced medicine until within ten days of his death.” William told Charles that he had previously served in the Confederate army and there is a soldier by that name and the same age who enlisted on 12 June 1861 in the Hampton Legion at Columbia, South Carolina. William’s younger brother George Butler Strom (1846-1865) served in Co. D, 14th South Carolina Militia. He was taken prisoner at Petersburg in April 1865 and died on David Island in New York 6 weeks later. It appears William changed his name to James Harrison Strom at some point in his life. He died in Melvern, Kansas in 1892.

Letter 2

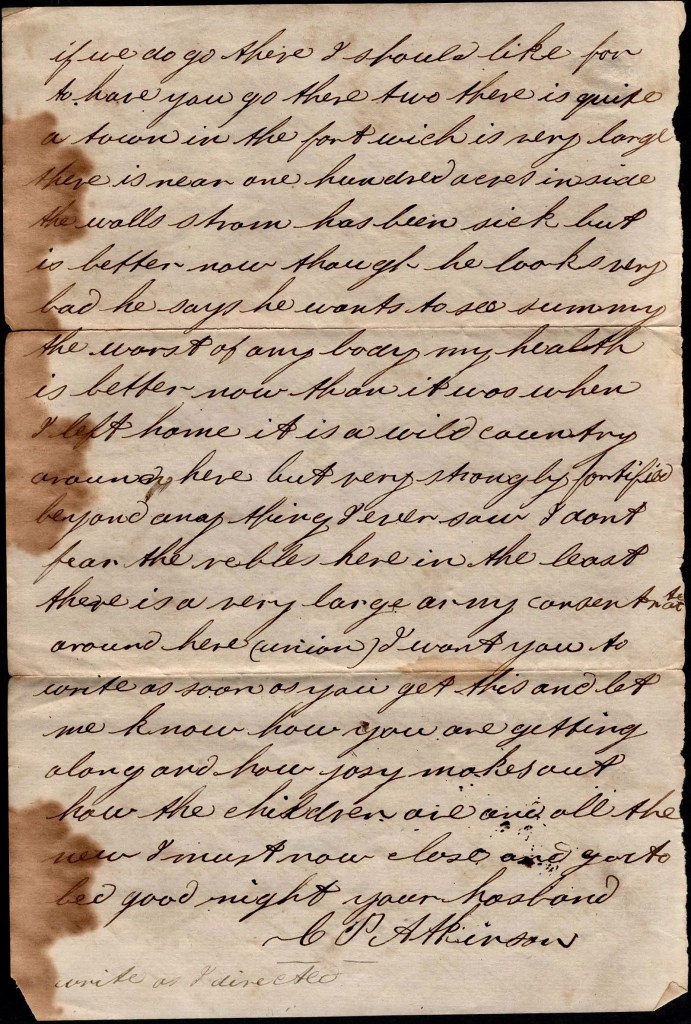

Suffolk, [Virginia]

March 6th 1862 [should be 1863]

My Dear Phebe,

I have at last reached my place of destination. I got here safe yesterday after being more than a week on the way. My journey was tedious but not uninteresting, though I was sick two days in the camp near Alexandria—two days with very poor accommodations—but I am in good health now and like the place very well. The fellows appeared to be very glad indeed to see me.

I was two days on the water going from Alexandria to Fortress Monroe. I then went to Norfolk and staid one day there before I could come to this place. The word is now that we are to be sent back to Fortress Monroe soon, to be permanently located there. I shall be glad if it is so for I think it is one of the prettiest places I ever saw. If we do go there, I should like for to have you to go there too. There is quite a town in the Fort which is very large. There is near one hundred acres inside the walls.

[William B.] Strom has been sick but is better now though he looks very bad. He says he wants to see Summy the worst of anybody. My health is better now than it was when I left home. It is a wild country around here but very strongly fortified—beyond anything I ever saw. I don’t fear the rebels here in the least. There is a very large army concentration around here (Union). I want you to write as soon as you get this and let me know how you are getting along and how Josy makes out, how the children are, and all the news. I must now close and get to bed. Good night. Your husband, C. P. Atkinson

Write as I directed.

Letter 3

Fort Halleck near Suffolk, Virginia

March 9, 1863

My dear Phebe,

I fear you are uneasy about me. I hope you will not give yourself any uneasiness on my account as I am quite well now—much better than I was when I left home. The weather is very pleasant here now—as warm as May. The daffodils are all in bloom as are many other flowers. The peach trees are nearly out in bloom. There are a great many camps around here and the men take a great deal of pride in fixing them up. They make little yards in front of their tents [illegible due to paper tear] exquisite manner with evergreens from the forest moss and the like. Many of them are exceeding pretty. They are a kind of miniature cottages and have a most home-like appearance. I have not had time to ornament mine yet but I guess I must get at it today.

The New Yorkers excel all others in these fancy homes but I think I can imitate them a little. I wish you could come here one of those pleasant days and take a stroll with me to see how nicely the men are fixed. We have no mud here. The lane is sandy. I am going to send you some cotton seed to plant one of these days. The little seeds that I send you in this letter are a beautiful species of evergreen. I got the seed from a tree in the cemetery near Alexandria. you can plant them and see if they will grow.

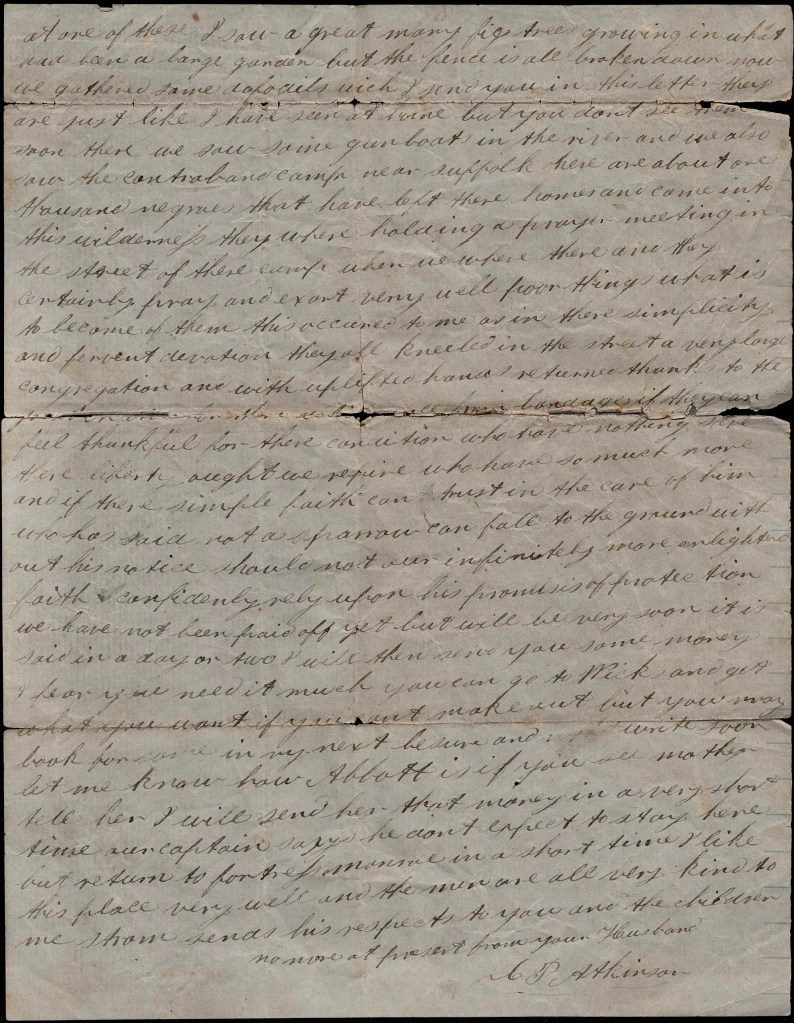

I took a walk yesterday afternoon with my friend Mr. Roberts down to the Nansemond River. We saw some very pretty homes but the owners had left and they were occupied by officers as quarters. At one of these I saw a great many fig trees growing in what had been a large garden but the fence is all broken down now. We gathered some daffodils which I send you in this letter. They are just like I have seen at home but you don’t see them as soon as here.

We saw some gunboats in the river and we also saw the Contraband Camp near Suffolk. Here are about one thousand Negroes that have left their homes and come into this wilderness. They were holding a prayer meeting in the street of their camp when we were there and they certainly pray and exhort very well. Poor things! What is to become of them? this occurred to me as in their simplicity and fervent devotion they all kneeled in the street—a very large congregation—and with uplifted hand returned thanks to the great Creator for their deliverance from bondage. If they can feel thankful for their condition who have nothing save their liberty, ought we repine who have so much more? And if their simple faith can trust in the care of Him who has said not a sparrow can fall to the ground without His notice, should not our infinitely more enlightened faith confidently rely upon His promises of protection.

We have not been paid off yet but will be very soon; it is said in a day or two. I will then send you some money. I fear you need it much. You can go to Wick and get what you want if you can’t make out but you may look for some in my next. Be sure and write soon. Let me know how Abbott is. If you see Mother. tell her I will send her that money in a very short time. Our captain says he don’t expect to stay here but return to Fortress Monroe in a short time. I like this place very well and the men are all very kind to me. Strom sends his respects to you and the children. No more at present. From your husband, — C. P. Atkinson

Letter 4

Fort Halleck near Suffolk, Virginia

March 28, 1863

My dear Phebe,

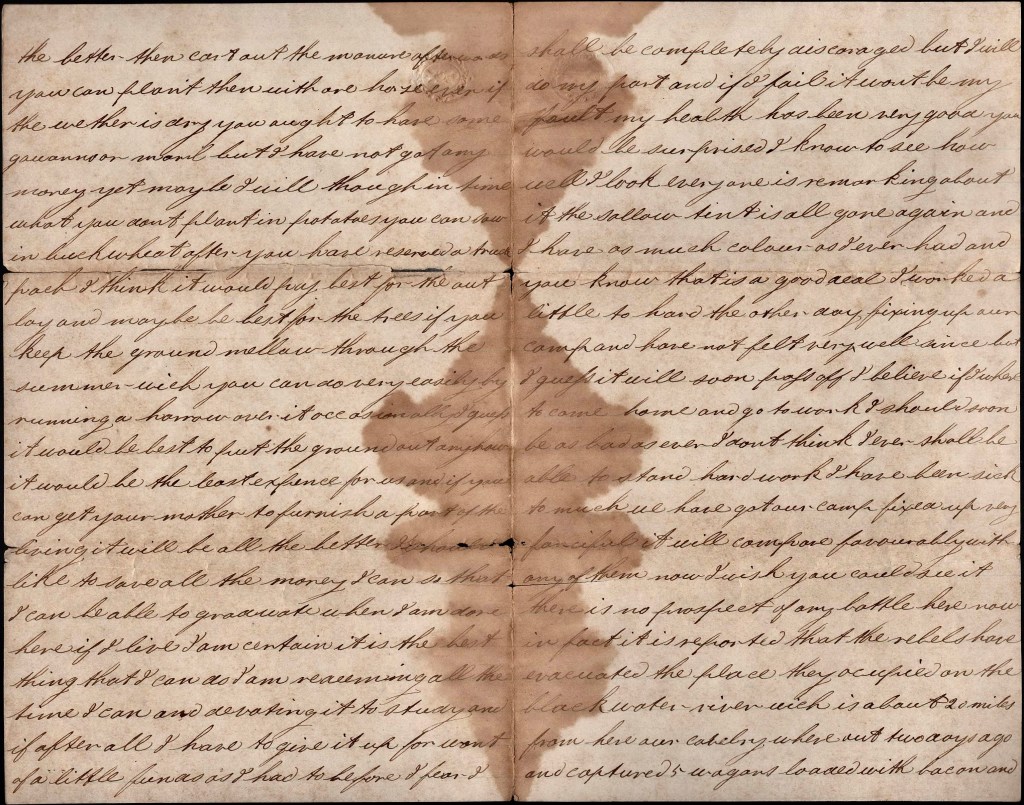

I received your letter of the 20th several days ago but was out of paper and could not answer it till now. You will therefore excuse me for delay. It afforded me great pleasure to hear that you were well. There is nothing of so much importance to me for while you are well, you can get on somehow but I am sorry to hear that Josy don’t suit. But if you think you can get along without him, let him go. you must use your own judgement. Maybe you can get Carry to gear [?] for you to go to church. I wish I were home so that I could see to you a little but it seems I can’t be. I intended to put the manure on potatoes. In the young peach orchard, commence at the road and plant as far as it goes. I think that Harvey would plant them for you on shares perhaps. I want you to have the whole field plowed up as soon as you can this spring—the sooner the better, Then cart out the manure often as you can plant…. If the weather is dry, you ought to have some guano or marle but I have not got any money yet. Maybe I will though in time. What you don’t plant in potatoes, you can sow in buckwheat after you have reserved a truck patch. I think it would pay best for the outlay and maybe be best for the trees if you keep the ground mellow though the summer which you can do every easily by running a harrow over it occasionally. I guess it would be best to put the ground out anyhow. It would be the least expense for us and if you can get your mother to furnish a part of the living, it will be all the better.

I would like to save all the money I can so that I can be able to graduate when I am done here—if I live. I am certain it is the best thing that I can do. I am reading all the time I can and devoting it to study and if after all I have to give it up for want of a little funds as I had to before, I fear I shall be completely discouraged. But I will do my part and if I fail, it won’t be my fault. My health has been very good. You would be surprised I know to see how well I look. Everyone is remarking about it. The sallow tint is all gone again and I have as much color as I ever had and you know that is a good deal. I worked a little too hard the other day fixing up our camp and have not felt very well since but I guess it will soon pass off. I believe if I were to come home and go to work, I should soon be as bad as ever. I don’t think I ever shall be able to stand hard work. I have been sick too much.

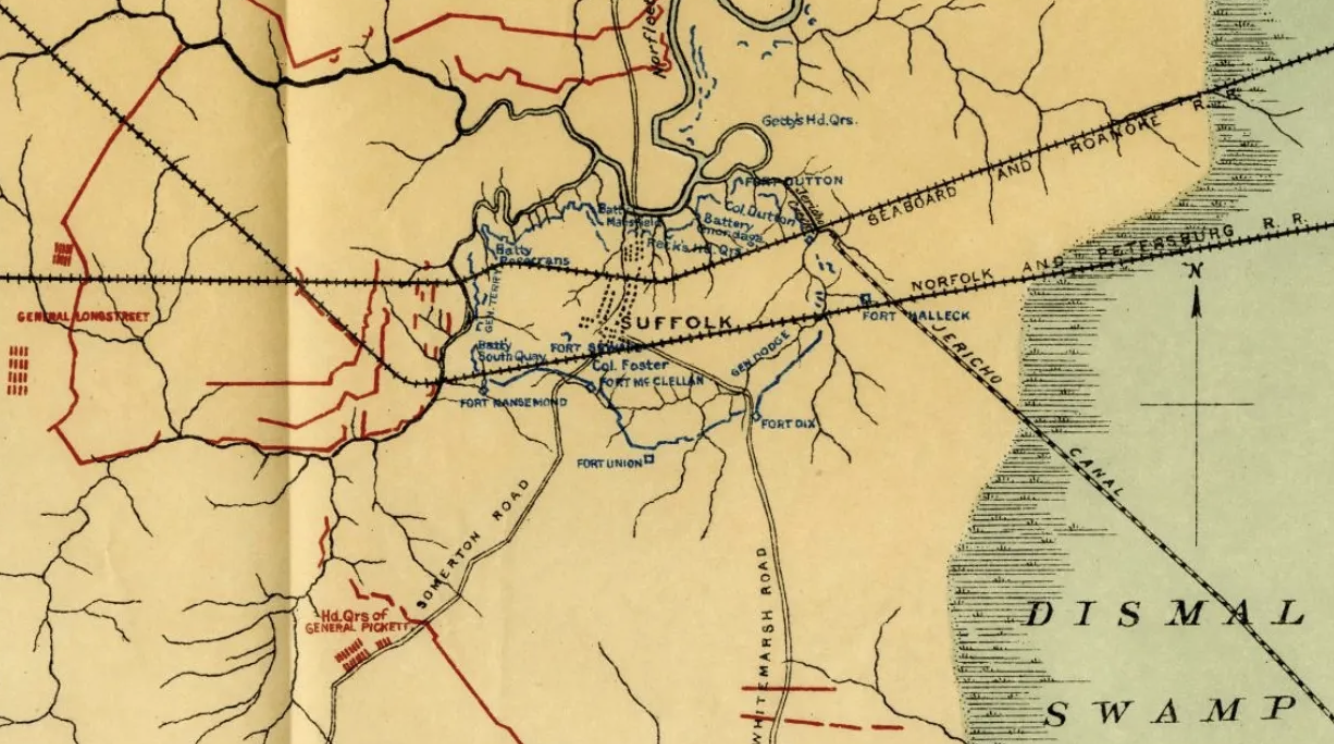

We have got our camp fixed up very fanciful. It will compare favorably with any of them now. I wish you could see it. There is no prospect of any battle here now. In fact, it is reported that the rebels have evacuated the place they occupied on the Blackwater River which is about 20 miles from here. Our cavalry were out two days ago and captured five wagons loaded with bacon and some prisoners. They said the rebels were nearly all gone. From present appearances, I can’t think this war can last much longer. I think I will get home by fall at any rate. The next three months must decide the case in some way, I think.

I believe there is a pay master here now paying off the men but as there are a great many to pay, it will take some time and I don’t know when we will get ours but I hope soon.

I saw Samuel Racock today. He is in the 25th New Jersey Regiment. I have swa James Whitaker several times. Smith Elwell is in the same regiment. They are about half a mile from us. You must do the best you can and take care of the children. I shall try to improve the time in such a way as will turn out to your advantage in the end, if I live to get home again. It is a consolation even here so far from home to have the assurance that there are those at home who feel an interest in my welfare and when in my morning and evening devotions I present your case at a throne of grace, I feel grateful to believe you do the same or me.

Strom has been very sick for three or four days. He is better this evening so that he is out. There are several taking medicine but none seriously ill. Tell Mother if you see her that her money will come soon. No more from your affectionate husband, — C. P. Atkinson

P. S. If you should go to the city, you will. have to take the children. You had better wait till I send some money.

Letter 5

Suffolk Hospital

April 29th 1863

My dear Phebe,

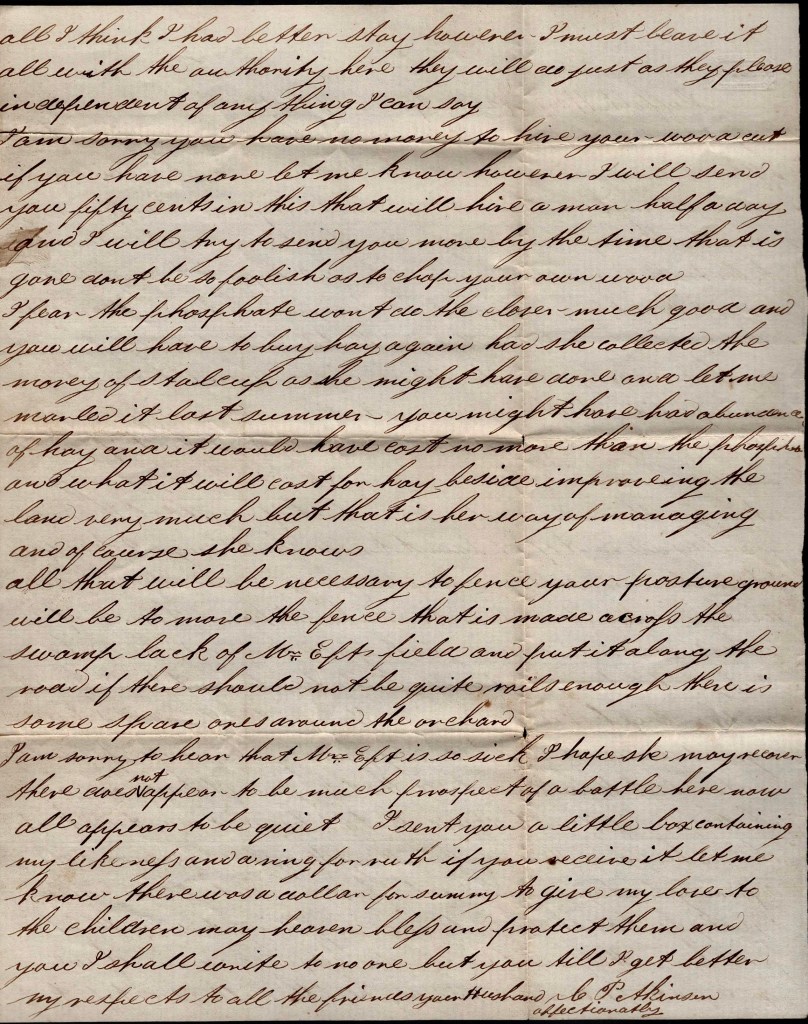

Yours of the 26th has been received. It affords me pleasure to hear that you and the children are well. My own health does not improve. I suffer very much. The captain says he thinks we will all move to Fortress Monroe in a week or so. I hope it may be the case as the change might be beneficial to me.

I came to the hospital to take charge but I have been confined to my bed nearly all the time since I came here. I have no appetite but my accommodations are very good and the fare is good if I could eat anything. I think if I get to Fortress Monroe I will be more likely to get my discharge than I would here but if my health will possibly admit of it, I don’t know but I ought to stay. It would be 20 dollars a month for you and the children which is more than I could make at home. Besides, if I were to come home sick, you know I would be subjected to a great deal of ill treatment from your mother which I dread more than all the rest.

I have a great desire to be with my family and would if I possibly could, but then I must see that they must have food and clothes and if I can’t secure that at home, I must seek it elsewhere. And then another thing, things were managed so poorly last year and I could have no control over the,. I really felt ashamed to have anything to do with it for I knew the fault would all be piled on me. If we go to Fortress Monroe and my health will admit of it at all, I think I had better stay. However, I must leave it all with the authority here. They will do just as they please independent of anything I can say.

I am sorry you have no money to hire your wood cut. If you have none, let me know. However, I will send you fifty cents in this. That will hire a man half a day and I will try to send you more by the time it’s gone. Don’t be so foolish as to chop your own wood.

I fear the phosphate won’t do the clover much good and you will have to buy hay again. Had she collected the money of Stalcup as she might have done and let me marled it last summer, you. might have had abundance of hay and it would have cost no more than the phosphate and what it will cost for hay besides improving the land very much but that is her way of managing and of course she knows.

All that will be necessary to fence your pasture ground will be to move the fence that is made across the swamp back of Mr. Eft’s field and put it along the road. If there should not be quite rails enough, there is some spare ones around the orchard. I am sorry to hear that Mrs. Eft is so sick. I hope she may recover.

There does not appear to be much prospect of a battle here now. All appears to be quiet. I sent you a little box containing my likeness and a ring for Ruth. If you receive it, let me know. There was a dollar for Summy too. Give my love to the children. May heaven bless and protect them and you. I shall write to no one but you till I get better. My respects to all the friends. Your husband, — C. P. Atkinson, affectionately.

Letter 6

Fort Seward

Suffolk, Virginia

May 30th 1862 [should be 1863]

My Dear Phebe,

It seems a long time since I heard from you. I have been looking for a letter from you for the last three days but none has arrived. Have you forgotten that you have a husband in the army, far from home among strangers, who has deposited all his happiness in your keeping, or have your letters not arrived, or do matters at home take up so much of your time that you can’t get time to write. Or has something occurred that would excuse you? It is going on two weeks since I’ve received a letter from you and I have at least three letters unanswered. I hope you won’t complain of me any more but I will not answer you until I hear your excuse. I told you when I was at home I wanted you to write every week and I would do the same.

As it regards the pants, if it is [too] much trouble, you need not get them and you can do as your a mind [to] about sending the box. If you do send one, you must be sure and write and let me know when you send it. Send your letter one day in advance of the box. You need not send it until I send you the money. We will most likely be paid off on Monday. The paymaster is here and had paid off nearly all the men here.

If you conclude to send me the gooseberries, I wish you would send me some lard and then I could make some pies. I could get flour and an oven here but you will have to secure it so that it won’t grease anything else you may send. If Carry can get the cloth cheap and you think you can make a coat by my summer coat, I would like to have one just to wear to church. I go to church now. There is service in the Episcopal Church twice every Sunday. But if you have not sent for the cloth, you need not. You may send my old coat and I will make out for pants.

I received a letter a few days ago from Jacob Hitehue. He stated that Mrs. Wood was very sick. I hope to hear of her being better. How is Mrs. Eft getting [along] and is Amanda living there yet? Thom. said to me the other evening if you would only come to see me and bring her with you, but then he said it would not be proper, he supposed, for her to come. From what little he says, I think he is making great calculations on Amanda provided the war closes favorably. It would be a pity if he gets disappointed. His health is much better.

I am as well as usual. I have gained in flesh considerably since I was sick. The weather has been quite cool for the past few days but dry. We had a little shower this afternoon. Write as soon as you get this. I shall not send any money till I hear from you. Tell Ruth and Summy I want to see them very bad and you also but I can’t tell when I ever shall. The Lord’s will be done. Your affectionate husband, — C. P. Atkinson

Letter 7

Fortress Monroe

June 21st 1863

My dear mother,

I received your kind letter a week or more ago but from the press of business incident to moving and other causes, I have not found leisure to answer it. I am glad that I can inform you that I am well and sincerely hope to hear of your being better.

I am now at Fortress Monroe where I expect I shall remain during my term of service. This is a very pleasant place indeed and I should suppose would be healthy. I am still in the hospital. We have a very good one here. It is a large, three-story brick building and everything is kept in the best style. There are quite a number of patients in the hospital—several that are very sick. I have been very busy for the past few days and had to be up a good deal of nights but they have sent in more help today and I think I will get some rest. I have superintended three wards.

I would like to see you all very much. I will try to get home in September if I can but it will depend somewhat on the amount of sickness here at that time. My address is Charles P. Atkinson, Post Hospital, Fortress Monroe. My love to all. Write as often as convenient. I will write again before long. Yours on, — Charles P. Atkinson

Letter 8

Fortress Monroe

July 1st 1863

My dear Phebe.

Yours of the 28th was received this morning. I am glad that your health continues as good as it does. My own is very good. I shall of course use all prudent care to preserve it. I am glad to hear that mother is so well. I think the men you have had making fence have nursed the job pretty well. However, I am glad it is done.

As it regards Ruthie going to school. I shall immediately write to the trustees about the matter. I think the teacher, trustees, and parents of children that would annoy or allow one to be annoyed that has passed through what she has have very little consideration or humanity about them.

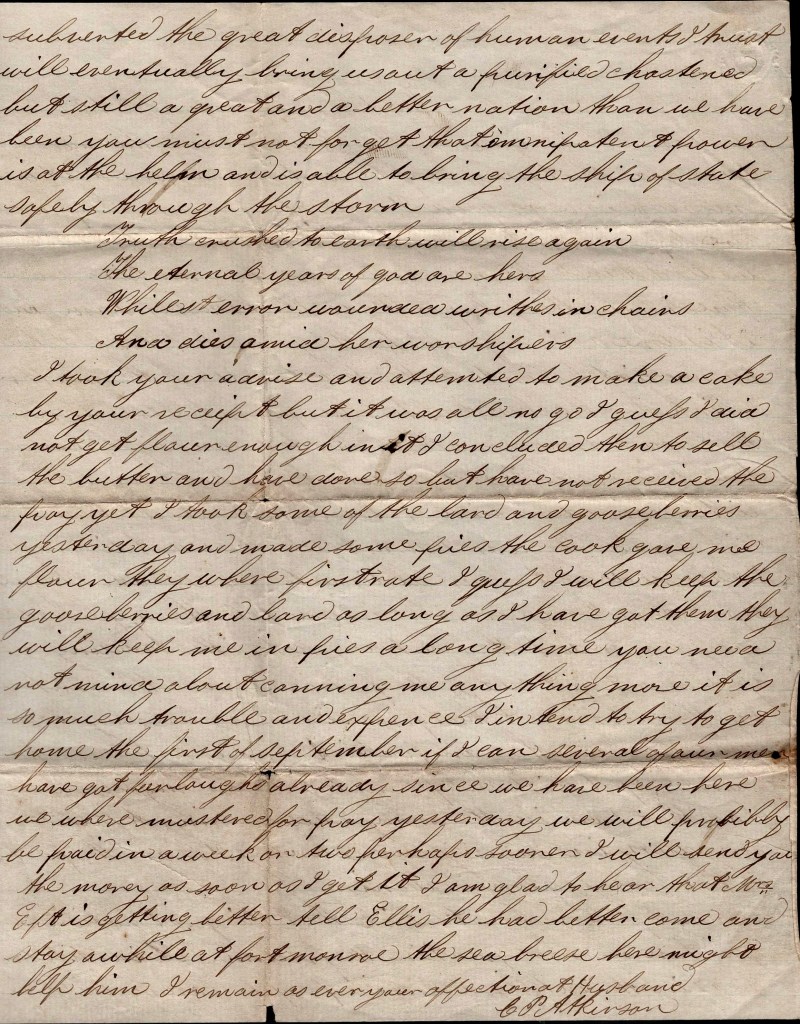

As it regards the war. I do not feel the least discouraged. I have no doubt of our ultimate success and I believe before another year rolls around, all the Copperheads may say or do to the contrary. Notwithstanding, you must not judge the patriotism of the country by the sentiments that prevail in your neighborhood. I believe there are patriots enough to save the country yet without Pennytown. For myself, I feel glad that I am in the army endeavoring to fulfill. my duty in saving our country. I fear the prestige of New Jersey’s glory in waning. I cannot for a moment believe that this great Nation, so great in resources, great in the freedom of its institutions, great in the intelligence of its people, can or will be subverted. The Great Disposer of human events, I trust, will eventually bring us out a purified, chastened, but still a great and a better Nation than we have been. You. must not forget that omnipotent power is at the helm and is able to bring the ship of state safely through the storm.

Truth crushed to earth will rise again

The Eternal years of God are hers

Whilst error wounded writhes in chains

And dies amid her worshippers

I took your advice and attempted to make a cake by your receipt but it was all no go. I guess I did not get flour enough in it. I concluded then to sell the butter and have done so but have not received the pay yet. I took some of the lard and gooseberries yesterday and made some pies. The cook gave me flour. They were first rate. I guess I will keep the gooseberries and lard as long as I have got them. They will keep me in pies a long time. You need not mind about canning me anything more. It is so much trouble and expense.

I intend to try to get home the first of September if I can. Several of our men have got furloughs already since we have been here. We were mustered for pay yesterday. We will probably be paid in a week or two—perhaps sooner. I will send you the money as soon as I get it. I am glad to hear that Mrs. Eft is getting better. Tell Ellis he had better come and stay awhile at Fort Monroe. The sea breeze here might help him. I remain as ever your affectionate husband, — C. P. Atkinson

Letter 9

Fortress Monroe

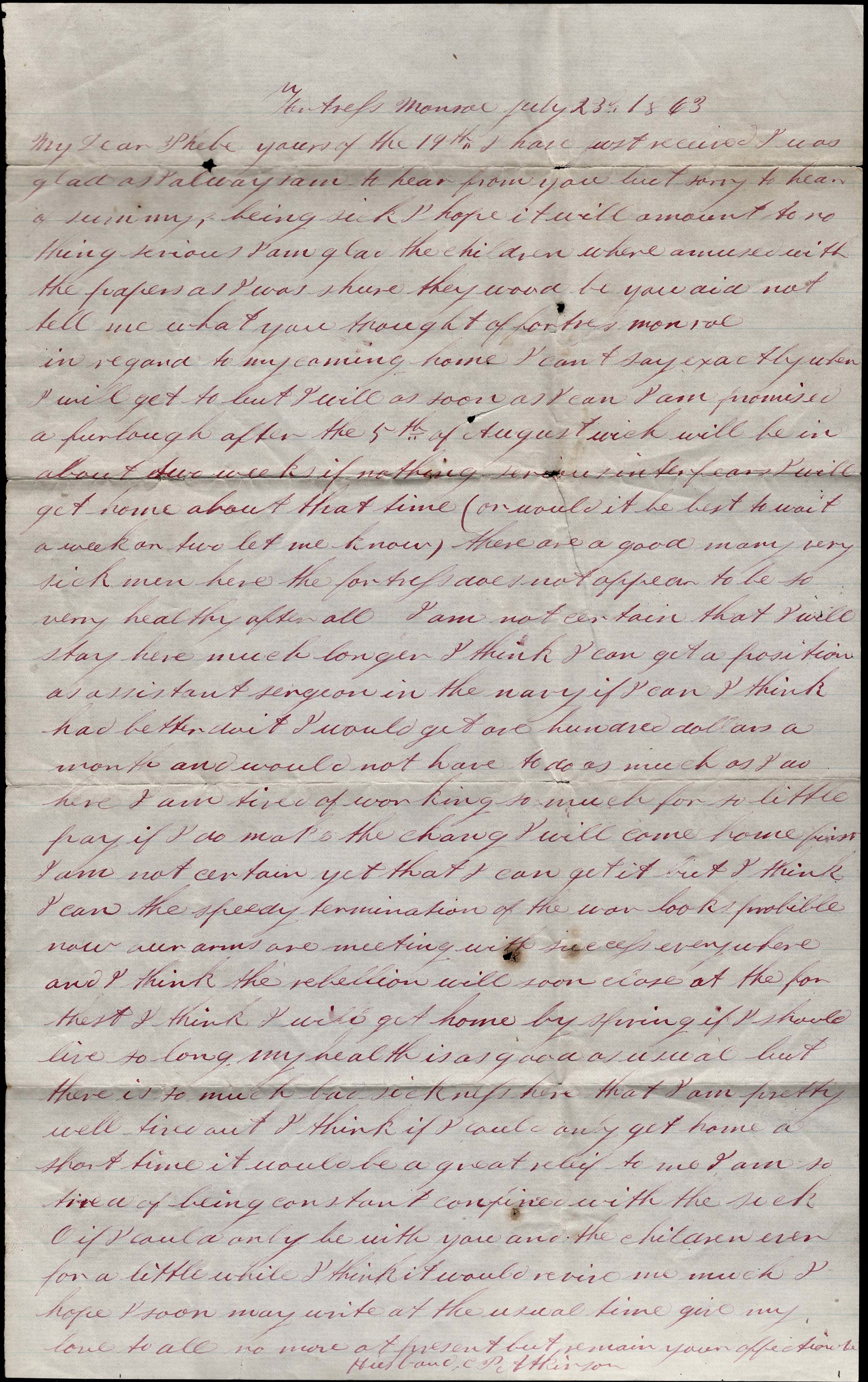

July 23, 1863

My dear Phebe,

Yours of the 19th I have just received. I was glad as always I am to hear from you but sorry to hear of Summy’s being sick. I hope it will amount to nothing serious. I am glad the children were amused with the papers as I was. I was sure they would be. You did not tell me what you thought of Fortress Monroe.

In regard to my coming home, I can’t say exactly when I will get to but I will as soon as I can. I am promised a furlough after the 5th of August which will be in about two weeks. If nothing serious interferes, I will get home about that time (or would it be best to wait a week or two. Let me know).

There are a good many sick men here. The Fortress does not appear to be so very healthy after all. I am not certain that I will stay here much longer. I think I can get a position as assistant surgeon in the Navy. If I can, I think I had better do it. I would get one hundred dollars a month and would ot have to do as much as I do here. I am tired of working so much for so little pay. If I do make the change, I will come home first. I am not certain yet that I can get it but I think I can.

The speedy termination of the war looks probable now. Our arms are meeting with success everywhere and I think the rebellion will soon close. At the farthest, I think I will. get home by spring if I should live so long. My health is as good as usual but there is too much bad sickness here that I am pretty well tired out. I think I could only get home a short time. I would be a great relief to me. I am so tired of being constantly confined with the sick. Oh if I could only be with you and the children even for a little while, I think it would revive me much. I hope I soon may. Write at the usual time. Give my love to all. No more at present but remain your affectionate husband, — C. P. Atkinson

Letter 10

Post Hospital

Fort Monroe

July 31st 1863

My dear Phebe,

I have just received your letter of the 28th and though I wrote yesterday. I have made it a rule to answer your letters immediately on the receipt of them. I will write again. I was very glad to hear that you were all so well. I hope and pray that you may remain so. I was also glad to hear that mother is so well. It rather surprises me to hear that she was able to visit you but I am glad she could do so. I sent Benny a drawing of Fort Monroe. I wonder if he got it? You wanted to know where I lived. I live inside the front of the house nearest the main gate on the left side of the entrance. You will recognize the main entrance by the bridge just back of the Hygenia Hotel.

I think you had a very good crop of wheat for the ground. You will have nearly enough for to supply you I should think. Did you get your turnips planted? I had been thinking you had better sow the cornfield down in clover for pasture and sow wheat over the road where you had clover this summer. It will be so late before you could sow wheat after corn, especially if Neal is slow in gathering it. If you conclude to sow clover in the corn, it ought to be done at once or as soon as he is done cultivating the corn which I suppose he is now or soon will be. If I don’t get home next week, I will send you money and I am afraid I will not be able to do so. I was speaking to the doctor about it this morning. He said he would get me a furlough if he could but he was afraid the Colonel would not approve of it. If he does not, of course I can’t come and you must make out the best you can.

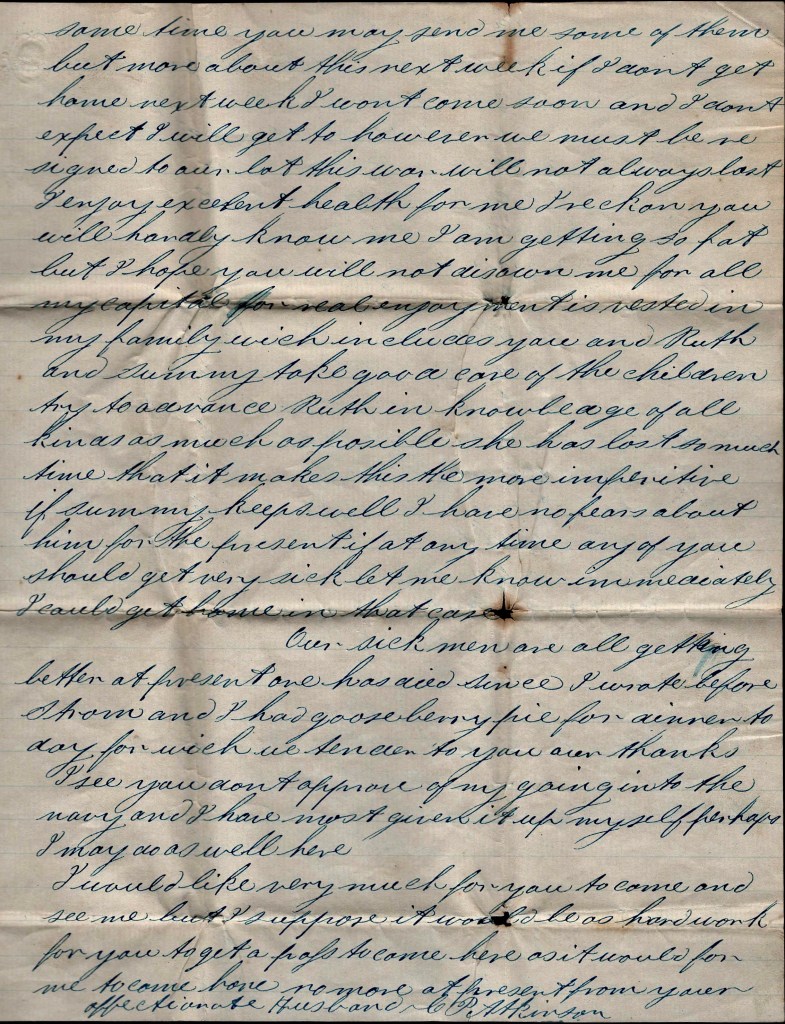

I also thought I would like to have the swamp Uncle Pete undertook to clean finished up or at least moved off. I wish you would see if you can get someone to do it by the job and what they would charge to just mow it off with a brush scyth and heap up the brush and burn it. See what it can be done for and let me know. I think it might be done for twenty or twenty-five dollars or less. I would like to come home and attend to it myself if I could but if I cannot, you must attend to it. How do your potatoes look? And what share does Doren have? How are the cranberries? Have the young peach trees grown much this summer? If I don’t get to come home, will you send me a little box of peaches that grow on them if I send you the money to pay expenses? I have had so much trouble with them. I thought I would like to have some small fruit just for curiosity if nothing else. If you were to wrap them up carefully and not have. them too ripe, they would come safe. If those pears in the garden get ripe about the same time, you may send me some of them. But more about this next week. If I don’t get home next week, I won’t come soon and I don’t expect I will get to. However, we must be resigned to our lot. This war will not always last.

I enjoy excellent health for me. I reckon you will hardly know me, I am getting so fat. But I hope you will. not disown me for all my capital for real enjoyment is vested in my family which includes you and Ruth and Summy. Take good care of the children. Try advance Ruth in knowledge of all kinds as much as possible. She has lost so much time that it makes this the more imperative. If Summy keeps well, I have no fears about him for the present. If at any time any of you should get very sick, let me know immediately. I could get home in that case.

Our sick men are all getting better at present. One has died since I wrote before. Strom and I had gooseberry pie for dinner today for which we tender to you our thanks. I see you don’t approve of my going into the Navy and I have most given it up myself. Perhaps I may do as well here. I would like very much for you to come and see me but I suppose it would be as hard work for you to get a pass to come here as it would be for me to come home. No more at present. From your affectionate husband, — C. P. Atkinson

Letter 11

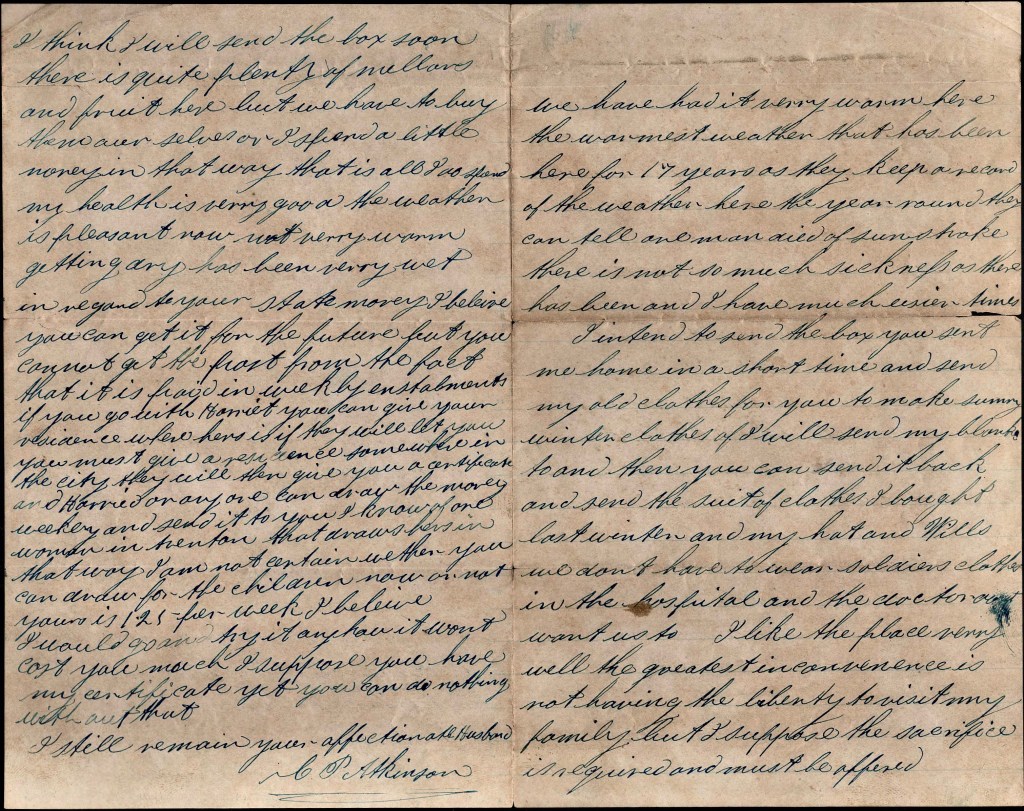

[Written from Fortress Monroe Post Hospital, probably in mid-August 1863]

…we have had it very warm here—the warmest weather that has been here for 17 years. As they keep a record of the weather here the year round, they can tell. One man died of sunstroke. There is not so much sickness as there has been and I have much easier times.

I intend to send the box you sent me home in a short time and send my old clothes for you to make Summy winter clothes of. I will send my blankets too and then you can send it back and send the suit of clothes I bought last winter and my hat and Will’s [too]. We don’t have to wear soldier’s clothes in the hospital and the doctor dob’t want us to. I like the place very well. The greatest inconvenience is not having the liberty to visit my family but I suppose the sacrifice is required and must be offered.

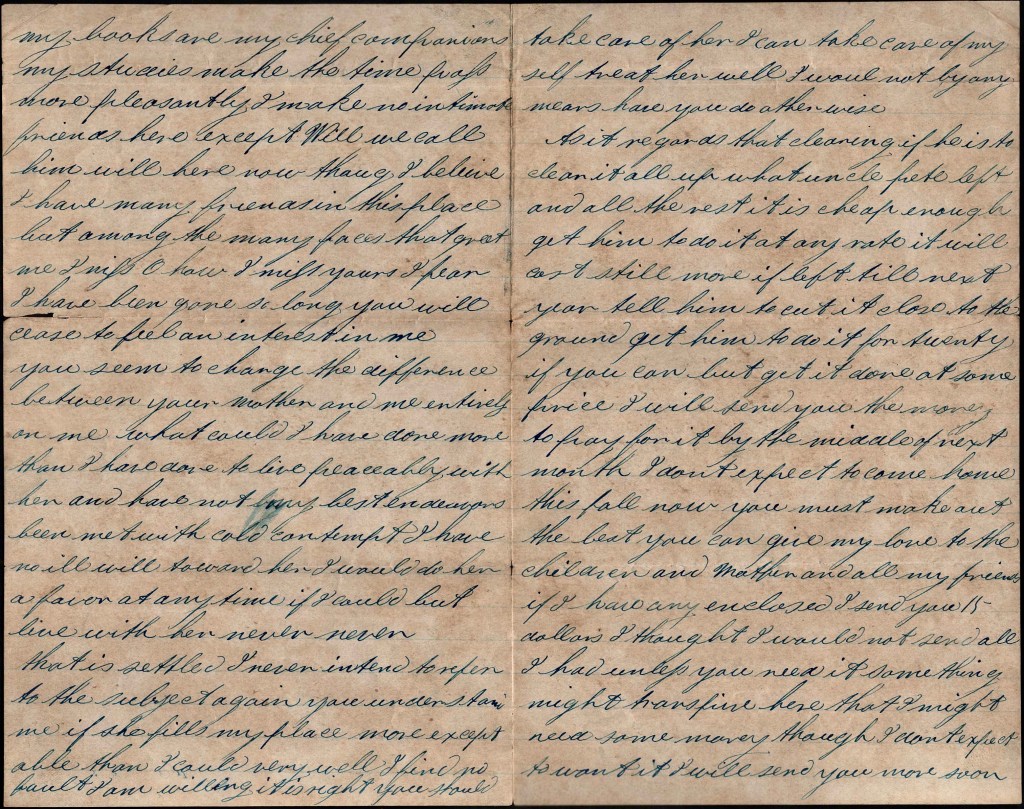

My books are my chief companions. My studies make the time pass more pleasantly. I make no intimate friends here except Will [Strom]—we call him “Will” here now—though I believe I have many friends in this place. But among the many faces that greet me, I miss—Oh how I miss—yours. I fear I have been gone so long you will dare to feel an interest in me. You seem to charge the difference between your mother and me entirely on me. What could I have done more than I have done to live peaceably with her and have not my best endeavors been met with cold contempt? I have no ill will toward her. I would do her a favor at any time if I could but live with her? Never, never! That is settled. I never intend to refer to the subject again, you understand me? If she fills my place more acceptable than I could, very well. I fond no fault. I am willing. It is right you. should take care of her. I can take care of myself. Treat her well. I would not by any means have you. do otherwise.

As it regards that clearing, if he is to clean it all up what Uncle Pete left and all the rest, it is cheap enough. Get him to do it at any rate. It will cost still more if left till next year. Tell him to cut it close to the ground. Get him to do it for twenty if you can but get it done at some price. I will send you the money to pay for it by the middle of next month. I don’t expect to come home this fall now. you. must make out the best you can. Give my love to the children and Mother and all my friends if I have any. Enclosed I send you 15 dollars. I thought I would send all I had unless you need it. Something might transpire here that I might need some money though I don’t expect to want it. I will send you more soon.

I think I will send the box soon. There is quite plenty of melons and fruit here but we have to buy them ourselves so I spend a little money that way. That is all I do spend. My health is very good, The weather is pleasant now—not very warm. Getting dry. Has been very wet.

In regard to your State money, I believe you. can get it for the future but you cannot get the past from the fact that it is paid in weekly installments. If you go with Harriet, you can give your residence where hers is if they will let you. You must give a residence somewhere in the city. They will then give you a certificate and Harriet or anyone can draw the money weekly adn send it to you. I know of one woman in Trenton that draws hers in that way. I am not certain whether you. can draw for the children now or not. yours is $1.25 per week, I believe. I would go and try it anyhow. It won’t cost you much. I suppose you have my certificate yet. You can do nothing without it.

I still remain your affectionate husband. — C. P. Atkinson

Letter 12

Post Hospital

Fortress Monroe

October 28th 1863

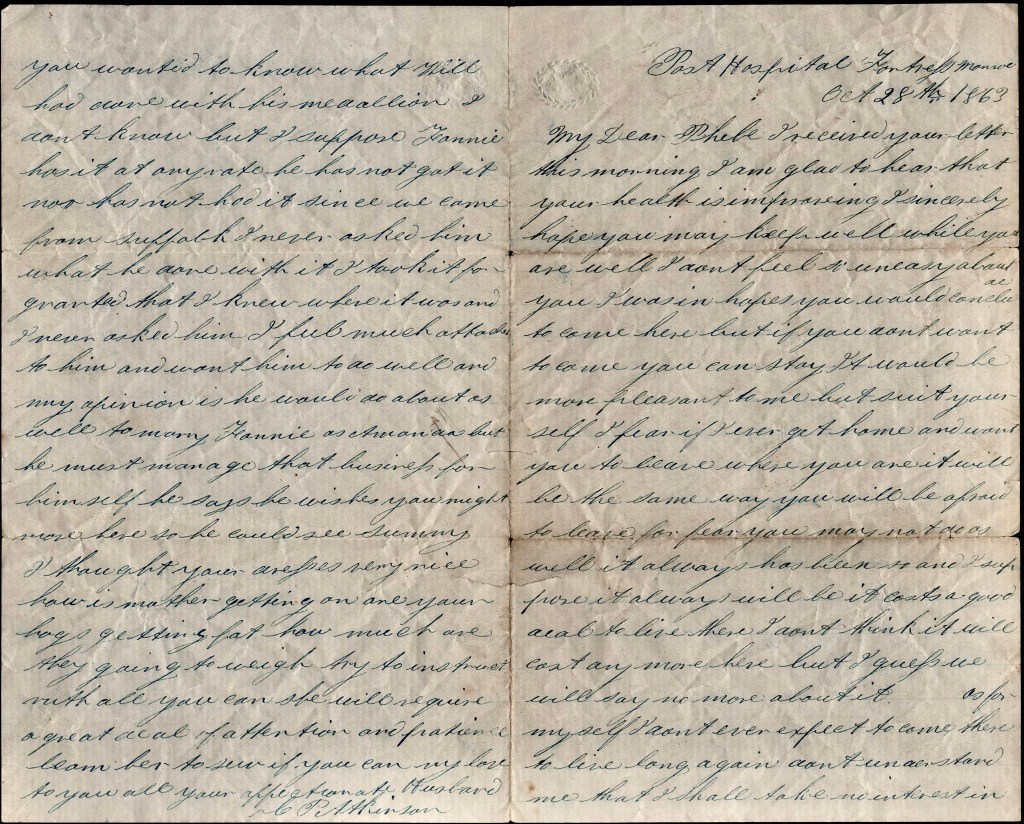

My dear Phebe,

I received your letter this morning. I am glad to hear that your health is improving. I sincerely hope you may keep well. While you are well. I don’t feel so uneasy about you. I was in hopes you would conclude to come here but if you don’t want to come, you can stay. It would be more pleasant to but suit yourself. I fear if I ever get home and want you to leave where you are, it will be the same way—you will be afraid to leave for fear you may not do as well. It always has been so I suppose it always will be. It costs a good deal to live there. I can’t think it will cost anymore here but I guess we will say no more about it.

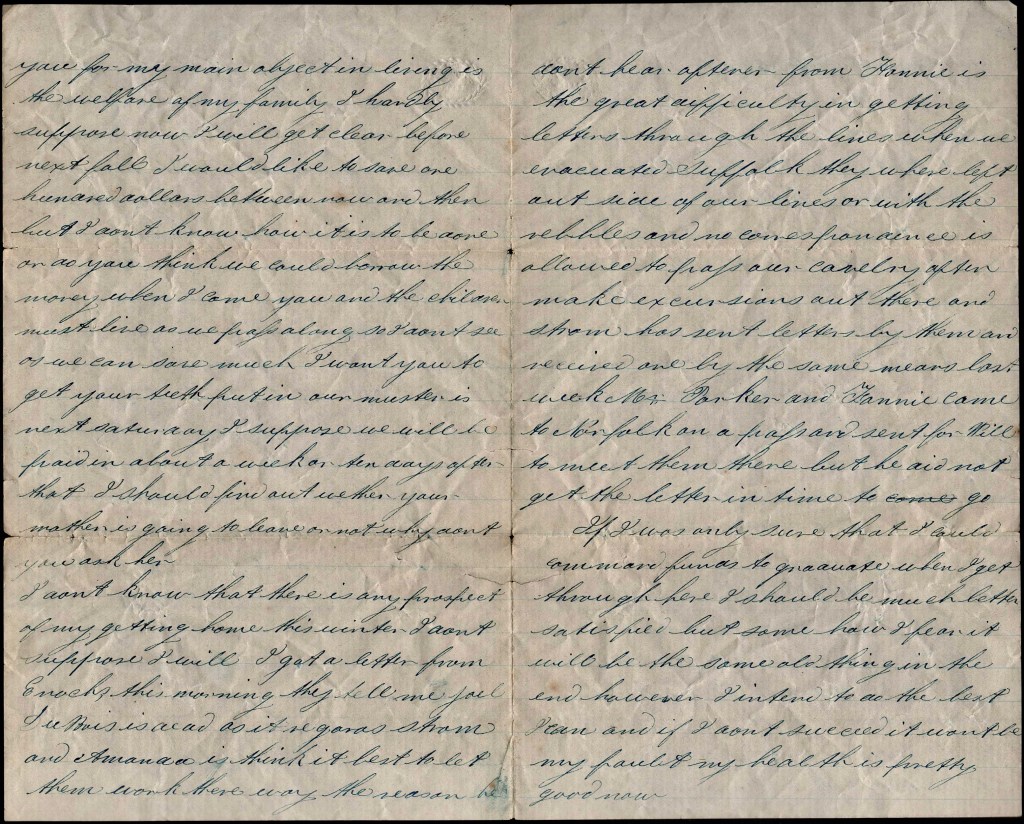

As for myself, I don’t ever expect to come there to live long again. Don’t understand me that I shall take no interest in you for my main object in living is the welfare of my family. I hardly suppose now I will get clear before next fall. I would like to save one hundred dollars between now and then but I don’t know how it is to be done or do you think we could borrow the money? When I come, you and the children must live as we pass along so I don’t see as we can save much. I want you to get your teeth put in. Our muster is next Saturday. I suppose we will be paid in about a week or ten days after that. I should find out whether your mother is going to leave or not. Why don’t you ask her?

I don’t know that there is any prospect of my getting home this winter. I don’t suppose I will. I got a letter from Enoch’s this morning. They tell me Joel DuBois is dead.

As it regards Strom and Amanda, I think it best to let them work their way. The reason he don’t hear oftener from Fannie is the great difficulty in getting letters through the lines. When we evacuated Suffolk, there were left outside of our lines or with the Rebels, and no correspondence is allowed to pass. Our cavalry often make excursions out there and Strom has sent letters by them and received one by the same means. Last week, Mr. Parker and Fannie came to Norfolk on a pass and sent for Will to meet them there but he did not get the letter in time to go.

If I was only sure that I could command funds to graduate when I get through here, I should be much better satisfied but somehow I fear it will be the same old thing in the end. However, I intend to do the best I can and if I don’t succeed, it won’t be my fault. My health is pretty good now.

You wanted to know what Will [Strom] had done with his medallion. I don’t know but I suppose Fannie has it. At any rate, he has not got it nor has not had it since we came from Suffolk. I never asked him what he done with it. I took it for granted that I knew where it was and I never asked him. I feel much attached to him and want him to do well and my opinion is he would do about as well to marry Fannie as Amanda but he must manage that business for himself. He says he wishes you might move here so he could see Summy.

I thought your dresses very nice. How is mother getting on? Are your hogs getting fat? How much are they going to weigh? Try to instruct with all you can. She will require a great deal of attention and patience. Learn her to sew if you. can. My love to you all. Your affectionate husband, — C. P. Atkinson

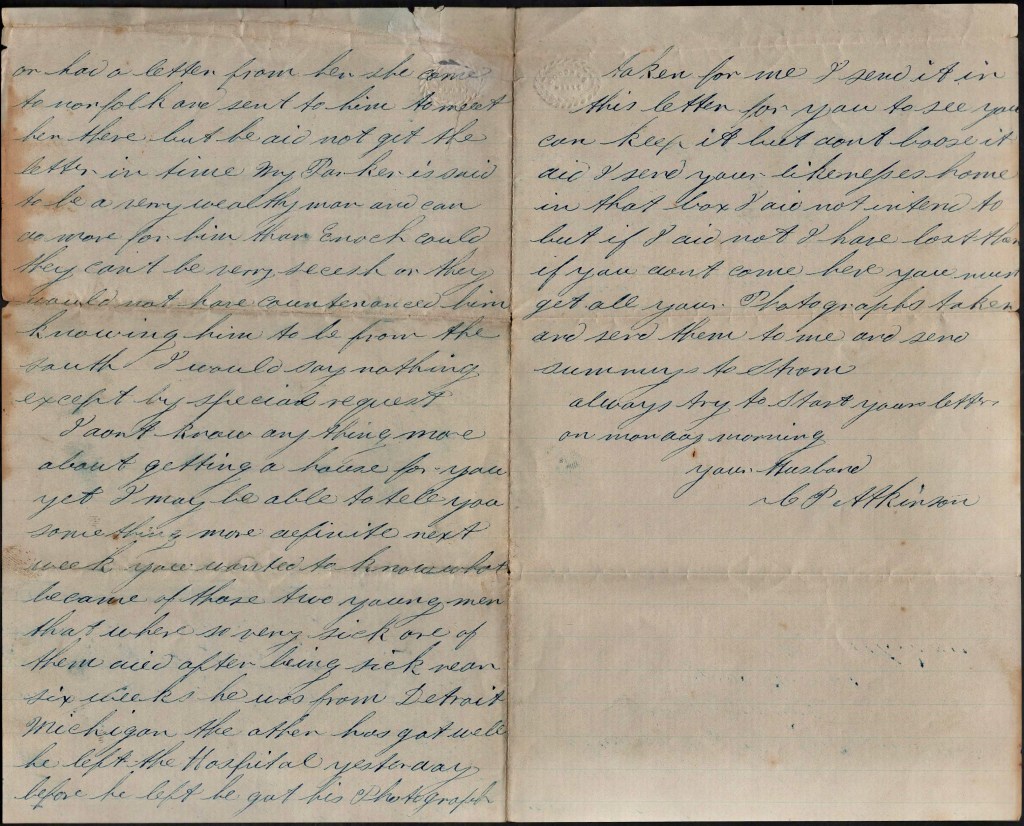

[Editor’s note: The sheet that follows is undated and most certainly was originally included with another letter. It may have been this letter or another one of about this time that no longer exists.]

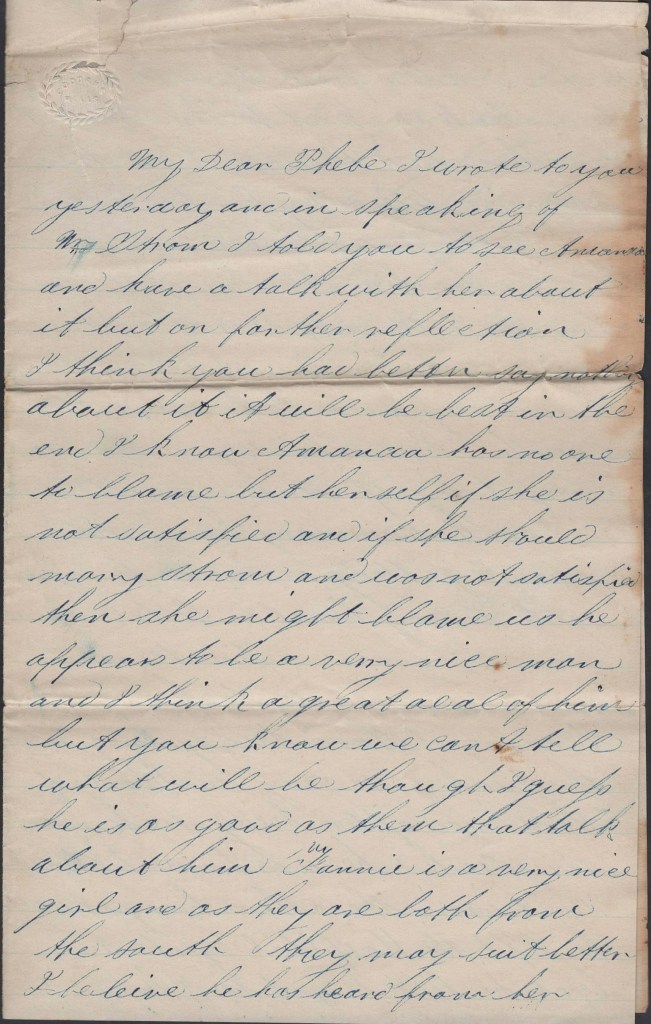

My dear Phebe,

I wrote to you yesterday and in speaking of Mr. [Will] Strom, I told you to see Amanda and have a talk with her about it but on further reflection, I think you had better say nothing about it. It will be best in the end. I know Amanda has no one to blame but herself if she is not satisfied and if she should marry Strom and was not satisfied then she might blame us. He appears to be a very nice man and I think a great deal of him, but you know we can’t tell what will be though I guess he is as good as them that talk about him.

Fannie is a very nice girl and as they are both from the South, they may suit better. I believe he has heard from her or had a letter from her. She came to Norfolk and sent to him to meet her there but he did not get the letter in time. Maj. Parker is said to be a very wealthy man and can do more for him than Enoch could. They can’t be very secesh or they would not have countenanced him knowing him to be from the South. I would say nothing except by special request.

I don’t know anything more about getting a house for you yet. I may be able to tell you something more definite next week. You wanted to know what became of those two young men that were so very sick. One of them died after being sick near six weeks. He was from Detroit, Michigan. The other has got well. He left the hospital yesterday. Before he left, he got his photograph taken for me. I send it in this letter for you to see. You can keep it but don’t lose it. Did I send your likenesses home in that box? I did not intend to but if I did not, I have lost them. If you don’t come here, you must get all your photographs taken and send them to me and send Summy’s to Strom.

Always try to start your letter on Monday morning. Your husband, — C. P. Atkinson

Letter 13

Camp Hamilton

Fortress Monroe, Virginia

January 11, 1864

My dear Phebe,

Yours came to hand today. I was glad to hear from you but sorry to hear Summy has been so sick, If he gets the croup again, give him the cough syrup that you made. That is the best thing that I know of. With good nursing, it will effect a cure. I regret that I am not yet able to send you any money. I don’t know the reason we haven’t been paid off. I hope we may be very soon. You will have to sell your potatoes and turnips for present wants and I will remit so soon as I receive my pay. Frank told me the price of the pigs would be one dollar and a quarter. I thought that cheap enough. You need not expect much favor from Moses.

I will write to Charlie soon. I hope we may get him to farm. I think he would suit you. I think it would be a good thing to get him to stay with you all the time. Hen he could work out what leisure time he had. Did Elijah do that work on the peach trees? I think I would have all the peach orchard planted in turnips except what you want for truck patch. They will pay better than anything else and less expense to raise.

We have all had very bad colds here but no very cold weather yet. We had a little snow on the 8th about an inch deep. That is all we have had. It is the pleasantest winter I have ever seen so far—I mean the weather.

I spoke about you coming here. I don’t know that I should ever want you to do so. I would prefer to stay there as we have worked so hard to fix things there. If I thought we could do as well as elsewhere, but I want to practice medicine and I fear I could not do as well as I could in a new place. But I shall be governed by circumstances. I think I will get home next fall whether the war is over or not. Our captain says according to our enlistment, our time will be out next December. You must try to make out the best you can till that time and I will try to do the best I can also. I think the war will end before next fall.

There are a great many refugees coming in here and many other places. You can send the box when it suits you. I may get paid in a day or two. I want you to write regularly and let me know how things are going at home. Does Ruth improve any in her speech? Give my love to all my friends. I hope I may hear that Summy is well soon. I still remain your affectionate husband, — C. P. Atkinson

Letter 14

On board Flag of Truce Boat

Fortress Monroe, Va.

January 29th 1864

My dear mother,

It has been some time since I wrote to you and I thought I would employ a few moments in doing so.

Phebe wrote to me you had got home again. I hope you enjoy good health. I think of you very often and wish I was where I could do something for you. If Phebe can do anything for you, I am sure she will take a pleasure in doing so. If I am so situated that I can do nothing for you, I will try to do nothing that will cause you any trouble or in anyway dishonor you.

I believe this is my thirty-seventh birthday. I can scarcely realize that I am so old. It seems but a very short time since I was a boy running round with Abbott, Garvis, and Mary. What pleasant times we used to have together. Oh how sad it makes me feel to think that they are all gone and I can see them no more and I, away among strangers so far from home. But I believe I am in the performance of my duty and I shall try to faithfully perform it and when my work is done, I hope we may all be united again.

At present I am employed on the Flag of Truce Boat as surgeon’s steward—a very good situation. We have just returned from a trip up the James River to City Point about 80 miles from here and about 40 from Richmond. We took up a few prisoners, several ladies and children going to their friends in the South. The prisoners were exchanged for some of our men (I don’t exactly know how it was effected for there is no general exchange taking place). The women and children were transferred to the rebel boat that met us at City Point. We brought back one colonel, one captain, one private and four or five citizen prisoners, among them a Quaker preacher who was sent out of the Confederacy for refusing to fight. He told me he had been in prison for nine months, some of the time in a dungeon. Two or three ladies were in the party.

Our prisoners say they see very hard times in Richmond. A lawyer that came down with us showed me his ration for last Thursday. He kept it to show his friends in the North. I tool a drawing of the size of it. You will find it on the outside of this letter. It consisted of a piece of cornbread of that size made of course corn meal, not sifted, just such as you used to give your pigs when you had n’t anything else. Once a week he said they got a little piece of boiled beef about a quarter of a pound.

I must now close. My health is pretty good. Remember me to Ellis and Elizabeth and the children. I may be in Philadelphia soon. If I do, I will. try and get home if it is only for a few hours. Your affectionate son, — Charles P.

This is the circumference of the corn bread. I laid it on the paper and drew the mark around it. It was about two inches thick. One day’s rations for a lawyer, or anyone else I suppose.

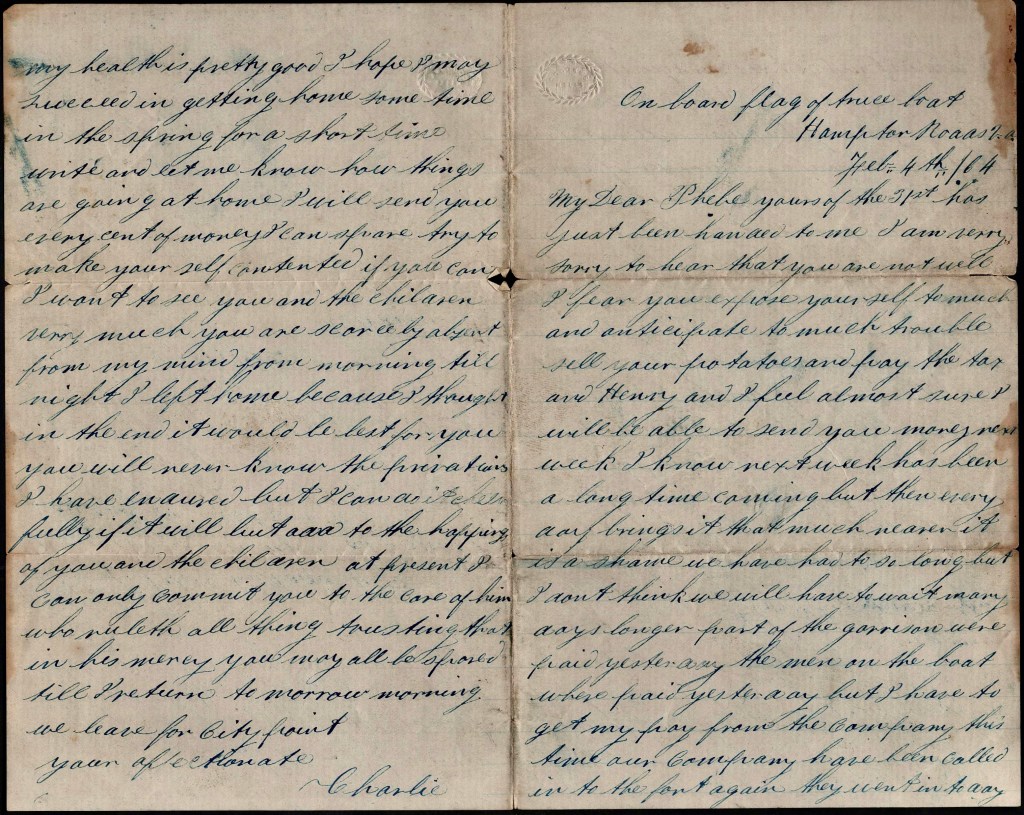

Letter 15

On board Flag of Truce Boat

Hampton Roads, Va.

February 4th 1864

My dear Phebe,

Yours of the 31st has just been handed to me. I am very sorry to hear that you are not well. I fear you expose yourself too much and anticipate too much trouble. Sell your potatoes and pay the tax and Henry and I feel almost sure I will be able to send your money next week. I know next week has been a long time coming but then every day brings it that much nearer. It is a shame we have had to so long but I don’t think we will have to wait many days longer. Part of the garrison were paid yesterday. The men on the boat were paid yesterday but I have to get my pay from the company this time. Our company have been called into the fort again. They went in today. You must not get discouraged if the people use you bad. I hope a better day is coming. This war will not always last and I should not wonder if some of those that are siting at home at their ease will have to take their turn yet.

I think I have got in the safest place there is in the army now. A flag of truce is never fired on. You wanted to know if I had to stay on the water all the time. My home is on the boat of course but the boat lies at anchor here about half the time and I can go on shore when I choose. My accommodations are the best I have had since I have been in the army. Don’t worry about sending me a box and please don’t expose yourself and work so hard as that. Won’t you for my sake. I intend to borrow some money and send you enough to square up when we do get paid which I think will be tomorrow but the boat is going to City Point tomorrow to take some things for our prisoners in Richmond so I can’t get to send you any money till I come back which will be about the middle of next week.

If Summy should get the scarlet fever, wash him often in soda water and after each washing, run him all over with sweet oil and put an onion poultice to his throat. I hope he will not.

The surgeon yesterday gave me some shirts. they were sent by the Sanitary Committee. He said he thought I deserved them as much as anyone. He gave me one red flannel. It is very fine but I don’t think I would look well in a red shirt. I thought it might make Ruth a sack. I saw some ladies on the boat with red flannel sacks and I thought them very nice. The shirt is a large one. I will send you. a piece. If you thin kit would make her one, I will send it to you.

My health is pretty good. I hope I may succeed in getting home some time in the spring for a short time. Write and let me know how things are going at home. I will send you every cent of money I can spare. Try to make yourself contented if you can. I want to see you and the children very much. You are scarcely out of my mind from morning till night. I left home because I thought in the end it would be best for you. You will never know the privations I have endured but I can do it cheerfully if it will but add to the happiness of you and the children.

At present, I can only commit you to the care of Him who ruleth all things, trusting that in His mercy, you may all be spared till I return. Tomorrow morning we leave for City Point. Your affectionate, — Charlie

Letter 16

On board steamer New York

Fortress Monroe, Virginia

February 23, 1864

My dear Phebe,

I sent you a letter with $25 enclosed in it today. In the little book you will find the receipt. If the money don’t come, you must go to the Express agent and demand it. There is an agent on the railroad. I guess one will attend to it though I don’t anticipate any difficulty. You must present your receipt inside of thirty days. The little book is for Ruth Anna. I was up in Baltimore week before last and I bought it for her there. I bought Summy a horn but I can’t send it by mail. I shall send you a box soon. I will send it in that. I will send that shirt also.

I know you must feel very lonesome and I desire very much to come to you but as that cannot be, rest assured that I fully sympathize with you. You have the conciousness of having done your duty to comfort you if you have not no one can. If your children treat you as well as you have yours, you can have nothing to complain of. You know where to look for comfort in the hour of trial and sorrow. It is a consolation to know that we have a Savior that was Himself a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief and will always afford comfort to His true followers. Tell Ruth and Summy that Pappy says he wants them to try to be very good children and he will continue to pray for you all and come home again as soon as I can. And when peace returns again, we can say that we contributed our might toward that great result. My children shall have the satisfaction of knowing that their father done his duty in trying to perpetuate the liberties handed down to us all by our forefathers.

Tell Ruth Annie she must be a good girl and help you now and I will send her a very nice breast pin and a nice little box I have for her. Tell her she must read the book to Summy. Tell Summy I have a nice little bugle for him. I will try and send it next week.

I think I can send you $20.00 more by the last of next week. I think from what I have heard, we will get paid again by that time. If you will need more than that, let me know. It is about time that interest was paid. Has there been any provision made for that or can you make any? If you need fodder, I suppose you can get it of Staulcap and let it go toward your share of the rent. I wish there was someone you. could advise with about what had best be done. Wan could assist you if he would. James Garainer would be a good man but I don’t know whether he would, Don’t have Burroughs to have anything to do with it. Write me the particulars and then I can tell you better what to do. Try to get along if possible without any hard feeling. I hope your brothers will be generous enough to allow your right willingly but if they are contrary, got to Bridgeton and employ a lawyer for ten dollars. He would tell you how to act all the way through. Hold out for your right but get along the mildest way you can. — Charlie

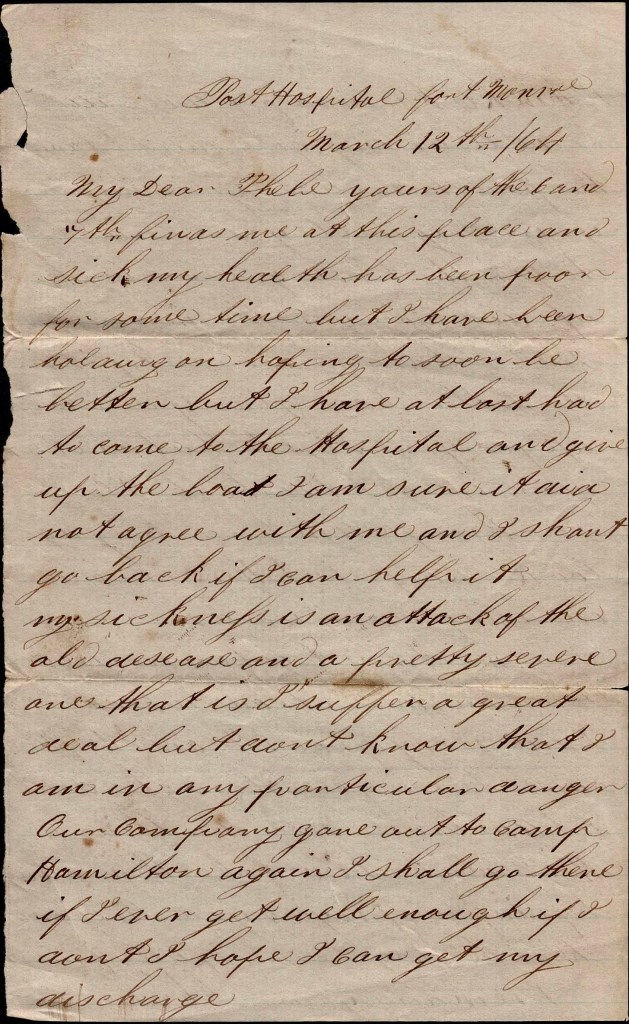

Letter 17

Post Hospital Fort Monroe

March 12, 1864

My dear Phebe,

Yours of the 6th and 7th finds me at this place and sick. My health has been poor for some time but I have been holding on hoping to soon be better but I have at last had to come to the hospital and give up the [Flag-of-Truce] boat. I am sure it did not agree with me and I shan’t go back if I can help it. My sickness is an attack of the old disease and a pretty severe one—that is, I suffer a great deal, but don’t know that I am in any particular danger.

Our company[has] gone out to Camp Hamilton again. I shall go there if I ever get well enough. If I don’t, I hope I can get my discharge. I think Charlie’s offer will do as well as any. You might farm the peach orchard yourself or your boy. Will you be able to get that new ground broke up? Did you get the money I. sent? I have no account of it in the letter. I am glad you stand up for your rights but don’t let your ire get too high. I could see through Ambrose long ago. Look sharp but there. is no use in using many words.

You must try to get clover seed sown and the oats and wheat. I am very glad Mr. and Mrs. Ward came to see you through. Don’t let Ambrose sell the things there. Make him take them away. Hoping and praying your lives and health may be mercifully preserved, I remain your, — Charlie

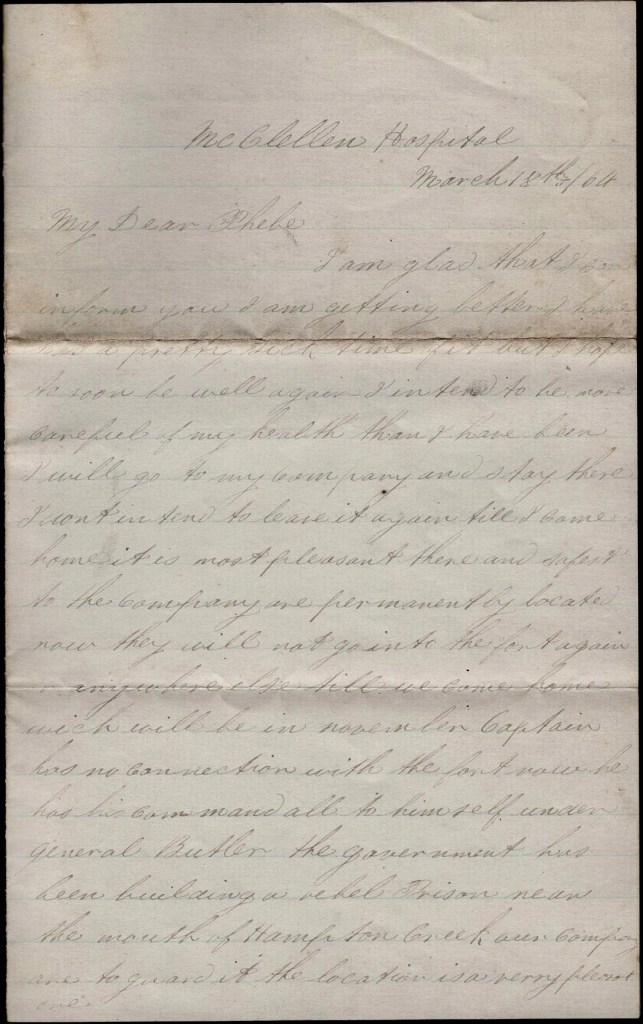

Letter 18

McClellan Hospital

March 18th 1864

My dear Phebe,

I am glad that I can inform you I am getting better. I have had a pretty sick time of it but I hope to soon be well again. I intend to be more careful of my health than I have been. I will go to my company and stay there. I don’t intend to leave it again till I come home. It is most pleasant there and safest too.

The company are permanently located now. They will not go into the fort again or anywhere else till we come home which will be in November. Captain has no connection with the fort now. He has his command all to himself under General Butler. The government has been building a rebel prison near the mouth of Hampton Creek. Our company are to guard it. The location is a very pleasant one. We can get clams by the cart load for the picking up and fish and oysters are plenty. I think I can send you a barrel of ish sometime this summer very cheap. I can buy them for a trifle and salt them myself.

The weather is pleasant. I look out today and think I would like to be at home fixing the garden for you. I think Summy and Ruth would help me but I will not have that pleasure this spring. But if we all live, I hope this is the last spring I will be away from you. I would rather stay now. I am here till fall if I can. Then I will be free from all drafts [even] if the war lasts ten years. They have passed a law that all men that have served two years are exempt from further duty.

How are you making out for money. I will try to send you some soon as I get well enough to go out. If I got to my company, I shall need a little to fix up with. I want to fix so I can do my own cooking so I can’t send you quite as much as I otherwise would. I suppose you must have got the last I sent though I have received no account of it. I think some of your letters have not reached me. I have only had three letters from you in two months. I wish you would write oftener. When you write again, tell me how to make sponge ginger bread. I want to make some.

I see Lincoln has made another call for 200,000 more men. I suppose the boys at home will begin to cringe and quake. It don’t disturb me in the least. I would rather be here than all the time standing in terror of being sent. My term is almost over. They have to begin theirs yet and I should not wonder if several of them had to go yet.

Feeling very thankful to our merciful protector for His care in restoring my health in a measure and praying that yours and the children may be precious in His sight, I remain your affectionate, — Charlie

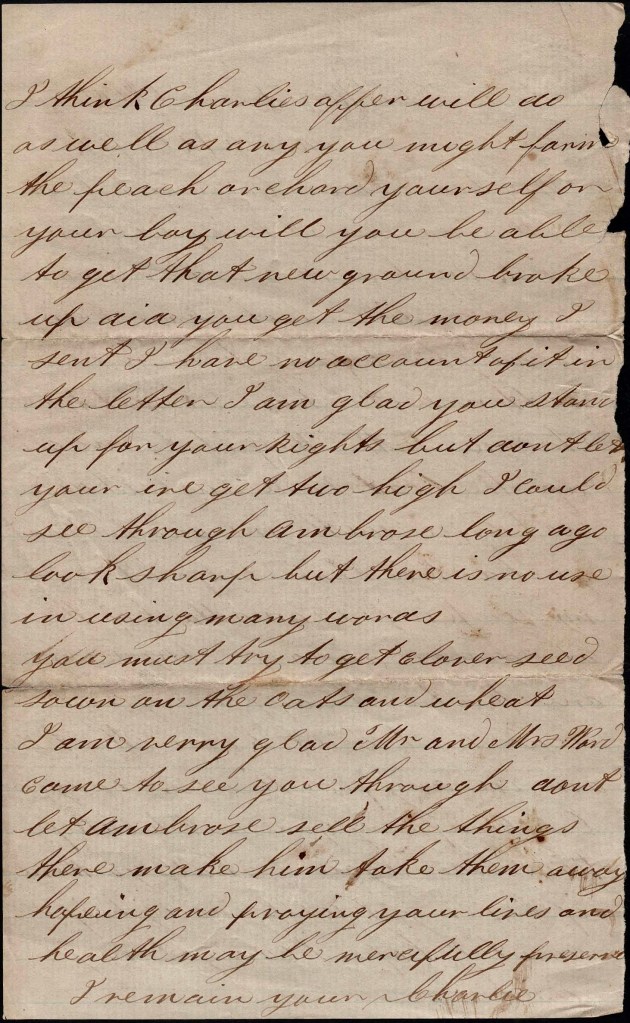

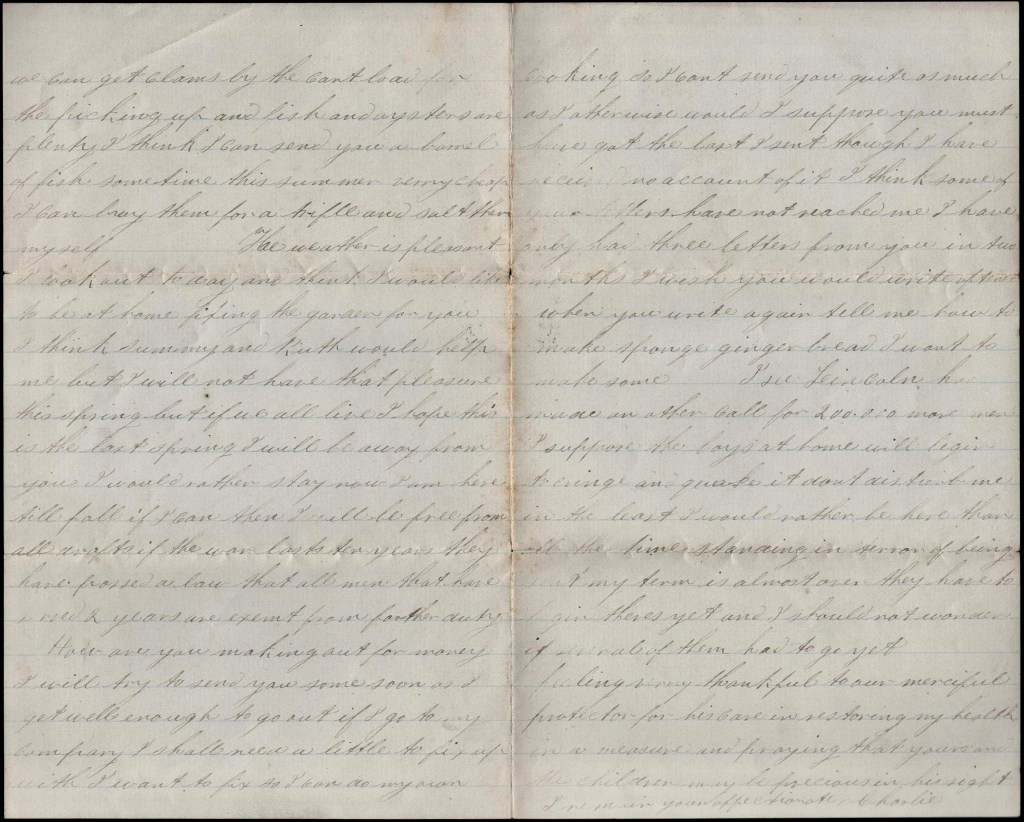

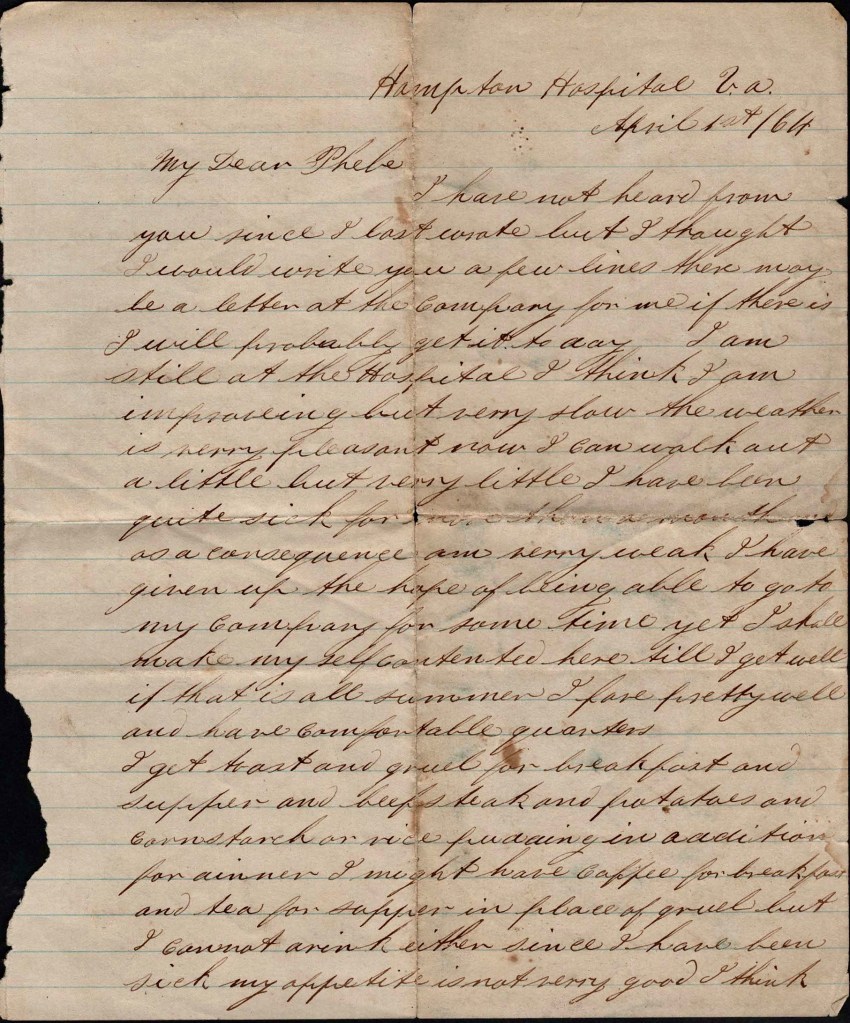

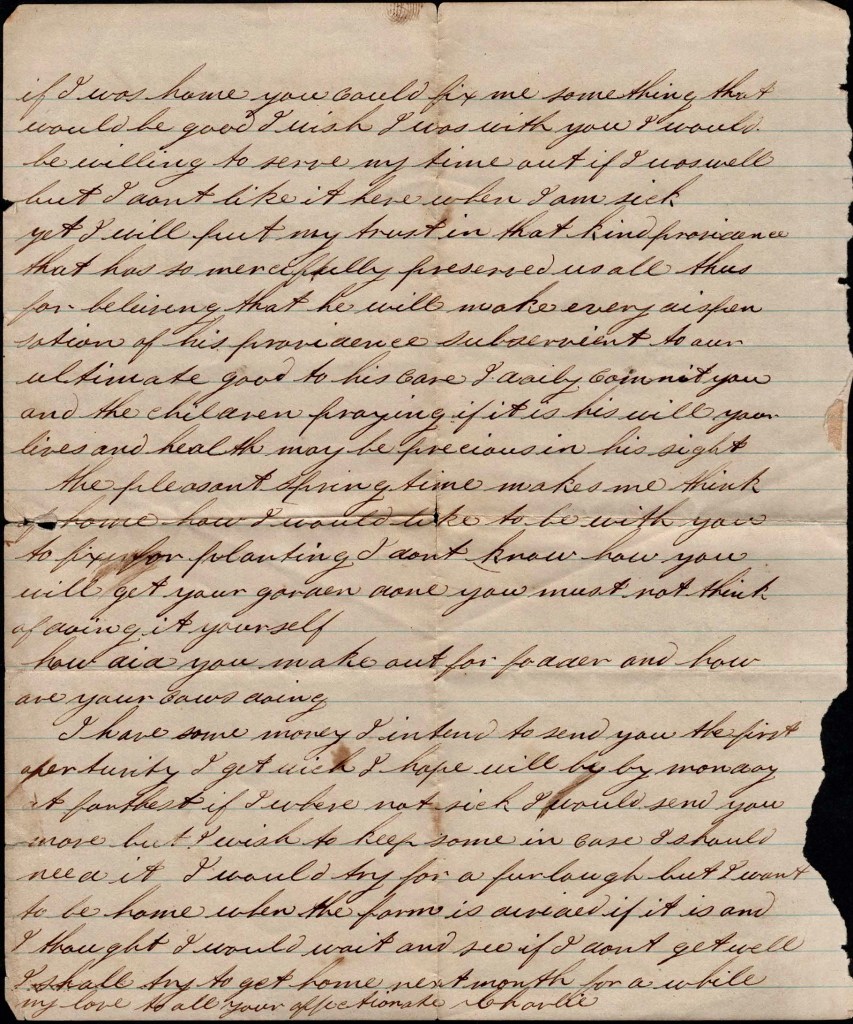

Letter 19

Hampton Hospital, Va.

April 1st 1864

My dear Phebe,

I have not heard from you since I last wrote but I thought I would write you a few lines. There may be a letter at the company for me, If there is, I will probably get it today. I am still at the hospital. I think I am improving but very slow. The weather is very pleasant now. I can walk out a little but very little. I have been quite sick for more than a month and as a consequence am very weak. I have given up the hope of being able to go to my company for some time yet. I shall make myself contented here till I get well if that is all summer. I fare pretty well and have comfortable quarters.

I got toast and gruel for breakfast and supper and beef steak and potatoes and cornstarch or rice pudding in addition for dinner. I might have coffee for breakfast and tea for supper in place of gruel but I cannot drink either since I have been sick. My appetite is not very good. I think if I was home you could fix me something that would be good. I wish I was with you. I would be willing to serve my time out if I was well but I don’t like it here when I am sick. Yet I will put my trust in that kind providence that has so mercifully preserved us all thus far, believing that He will make every dispensation of His providence subservient to our ultimate good to His care. I daily commit you and the children praying if it is His will your lives and health may be precious in His sight.

The pleasant spring times makes me think of home. How I would like to be with you to dix for planting. I don’t know how you will get your garden done. You must not think of doing it yourself. How did you make out for fodder and how are your cows doing?

I have some money I intend to send to you the first opportunity I get which I hope will be by Monday at farthest. If I were not sick, I would send you more but I wish to keep some in case I should need it. I would try for a furlough but I want to be home when the farm is divided, if it is, and I thought I would wait and see if I don’t get well. I shall try to get home next month for a while. My love to all. Your affectionate, — Charlie

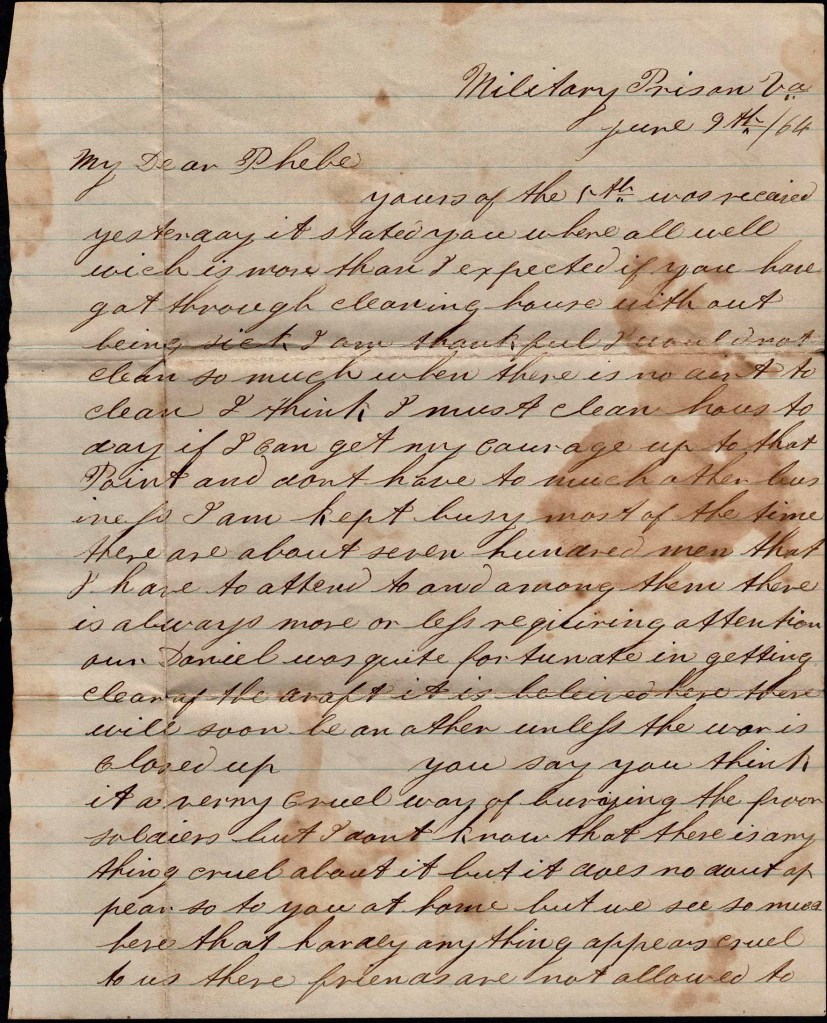

Letter 20

Military Prison [near Hampton, Virginia], Virginia

June 9, 1864

My dear Phebe,

Yours of the 5th was received yesterday. It stated you were all well which is more than I expected. If you have got through cleaning house without being sick, I am thankful. I wouldn’t clean so much when there is no dirt to clean. I think I must clean house today if I can get my courage up to that point and don’t have too much other business. I am kept busy most of the time. There are about seven hundred men that I have to attend to and among them there is always more or less requiring attention. Our Daniel was quite fortunate in getting clear of the draft. It is believed here there will soon be another unless the war is closed up.

You say you think it a very cruel way of burying the poor soldiers but I don’t know that there is anything cruel about it. But it does no doubt appear so to you at home. But we see so much here that hardly anything appears cruel to us. Their friends are not allowed to visit here now but they have a nice burial place and each soldier’s grave is marked with a headboard with his name, regiment, and date of his death written upon it and when cold weather comes the friends are allowed to come and take them home if they wish.

I guess my brothers are about as much interested in my welfare as yours are in yours. I suppose Jonny feels rather above owning a soldier for a brother. He is said to be very patriotic in the tongue but I guess it don’t get much farther.

I intend to write to Mother soon. I went cherrying again on Monday and made out pretty well. I used the last I got yesterday. Cherries are about gone here now. I suppose they are hardly ripe with you yet. Blackberries begin to ripen here. They are plenty. I have never seen a rose bug in Virginia. I don’t [think] there are any here. I think [ ] done good work on the fence if he has done that well. Last spring it would not have cost you so much. A great many of the wounded have been sent North and there has not been many coming in the last week. I am well as usual. Do the children go to school? How does Ruth make out? Your affectionate, — Charlie

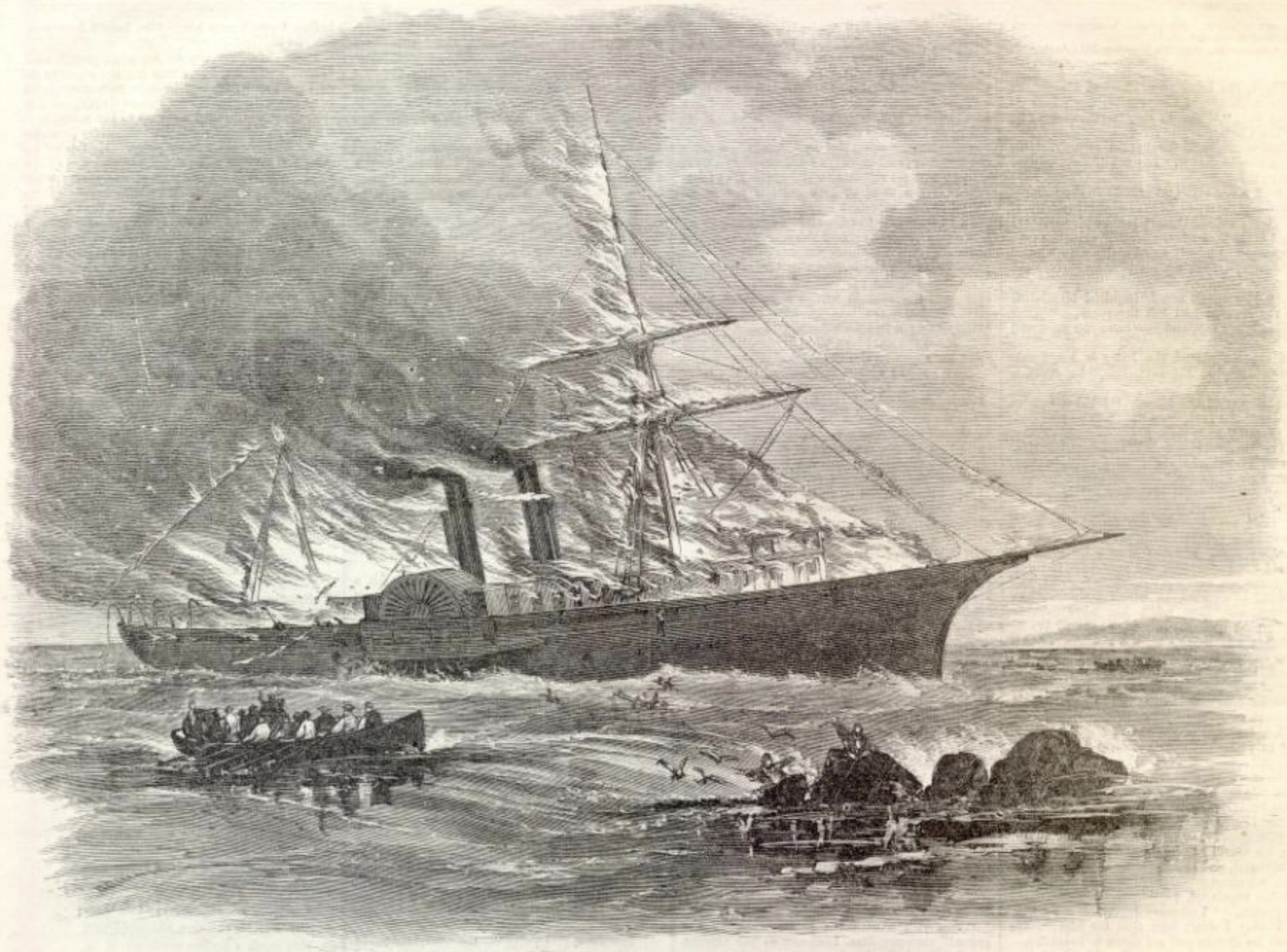

Letter 21

Camp Hamilton, Virginia

April 5th 1865

My dear wife,

I received your welcome letter today. I was very glad to hear from you but very sorry to hear you are so unwell. I feel thankful to know that the children keep well.

I am very sorry you have so much trouble to get help but I wouldn’t worry. Get along the easiest way you can. If you can’t get any work done, let it go. Don’t go out to digging yourself and getting sick. It is hard, I know, but it might have been worse if I had stayed at home. I am sure it would be worse to do as Wesby has done, don’t you think so, for there will be a lifelong disgrace in his conduct.

I suppose there has been a general rejoicing over the capture of Richmond there as well as here though I reckon you didn’t make so big a noise. It was the noisiest time here I ever heard. We have so many things here to make a big noise with and I assure you, everything was let loose. We got the news about ten o’clock on Monday and Oh! what a time we had. The cannon boomed from the Fort, the bells rang, the steamers whistled, drums beat, men cheered, while the poor rebels were the very picture of despair. I could not help but pity them. They had to witness all. those demonstrations of joy over the fall if their Capitol to them the source of the deepest grief.

I had a letter from Strom. He is going to remain at Norfolk or at least that is the calculation now. He says he don’t like the regiment at all. He expects to be made Hospital Steward. He had been examined and pronounced qualified for the position if he could bring a good commendation as to character. We sent him a very strong one so I expect he is all right.

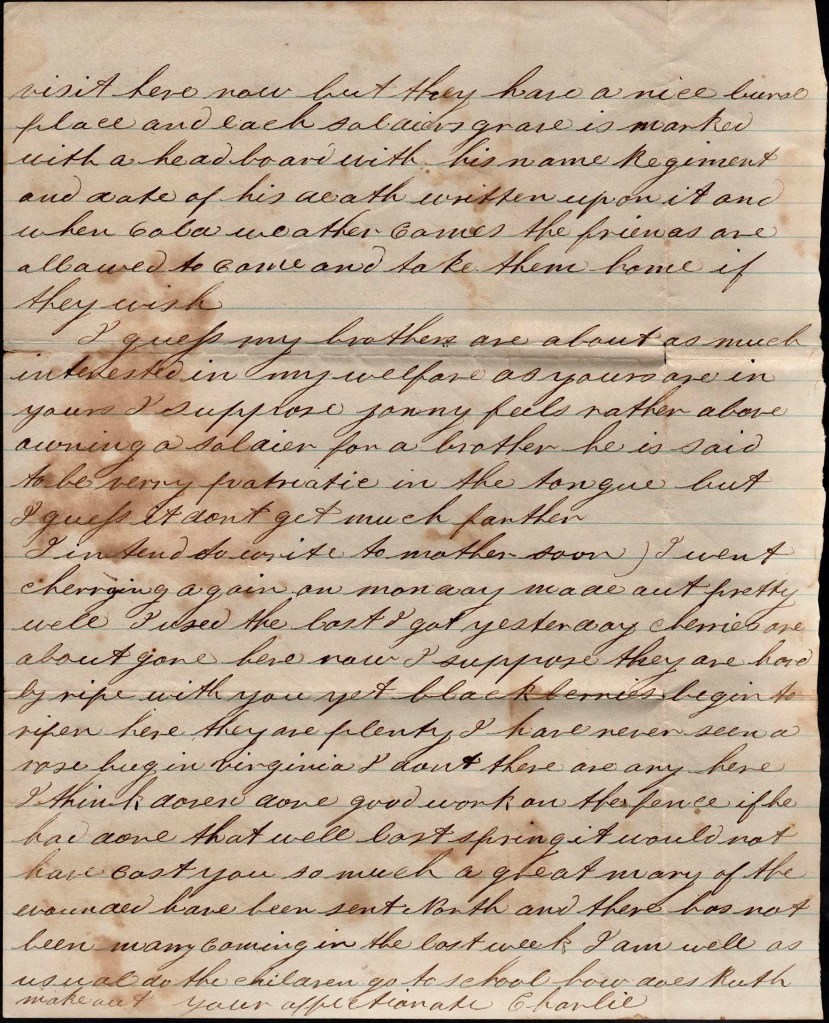

Jake was here Tuesday. He says nothing has been heard from the vessel yet. They begin to fear she is lost. I have not seen Moses since I returned. I believe he is well.

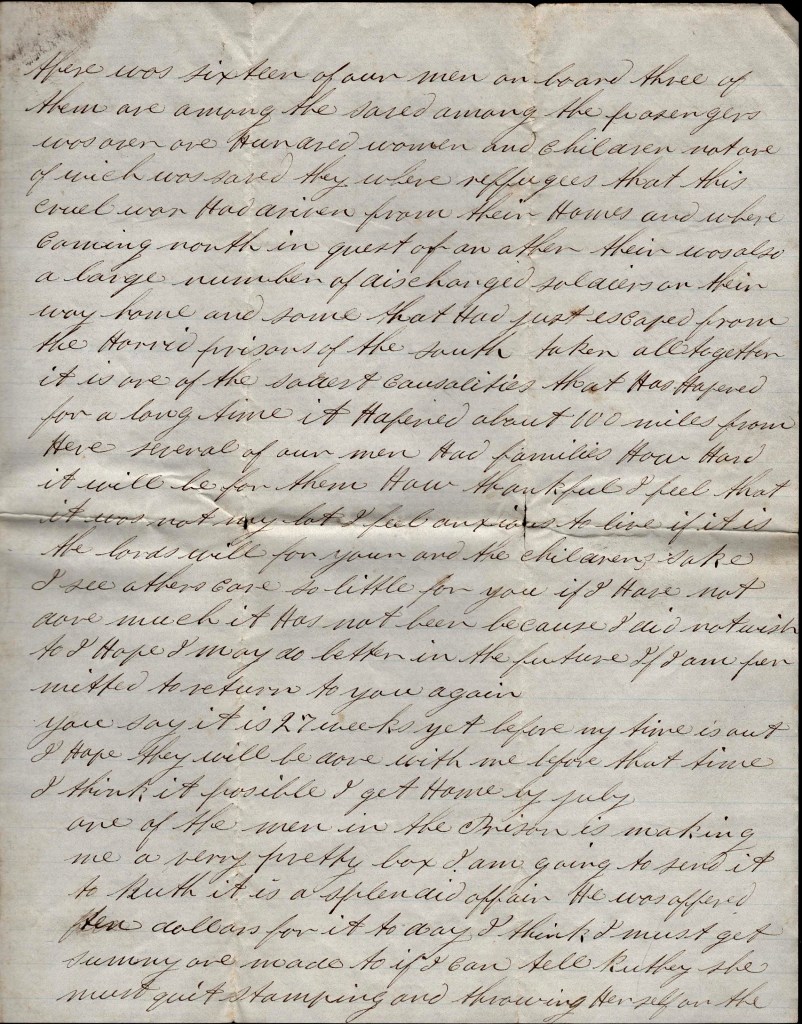

Our battery that has been so fortunate up to this time has met with a sad, sad calamity. Thirteen of our men were lost on the steamer General Lyon that was burned off Cape Hatteras as few days ago. They had been to Wilmington and were on their way back. There was over six hundred on board and only about 25 of which were saved. The fire originated in a barrel of kerosene oil and the flames spread so rapidly that nothing could be done. There were sixteen of our men on board. Three of them are among the saved. Among the passengers was over one hundred women and children—not one of which was saved. They were refugees that this cruel war had driven from their homes and were coming North in quest of another. There was also a large number of discharged soldiers on their way home and some that had just escaped from the horrid prisons of the South. Taken altogether, it is one of the saddest casualties that has happened for a long time. It happened about 100 miles from here. Several of our men had families. How hard it will be for them. How thankful I feel that it was not my lot but feel anxious to live, if it is the Lord’s will, for yours and the children’s sake. I see others care so little for you, if I had not done much it has not been because I did not wish to. I hope I may do better in the future if I am permitted to return to you again. [See: “The Tragic Fire and Sinking of the General Lyon Steamer” by Tom Clavin]

You say it is 27 weeks yet before my time is out. I hope they will be done with me before that time. I think it possible I get home by July.

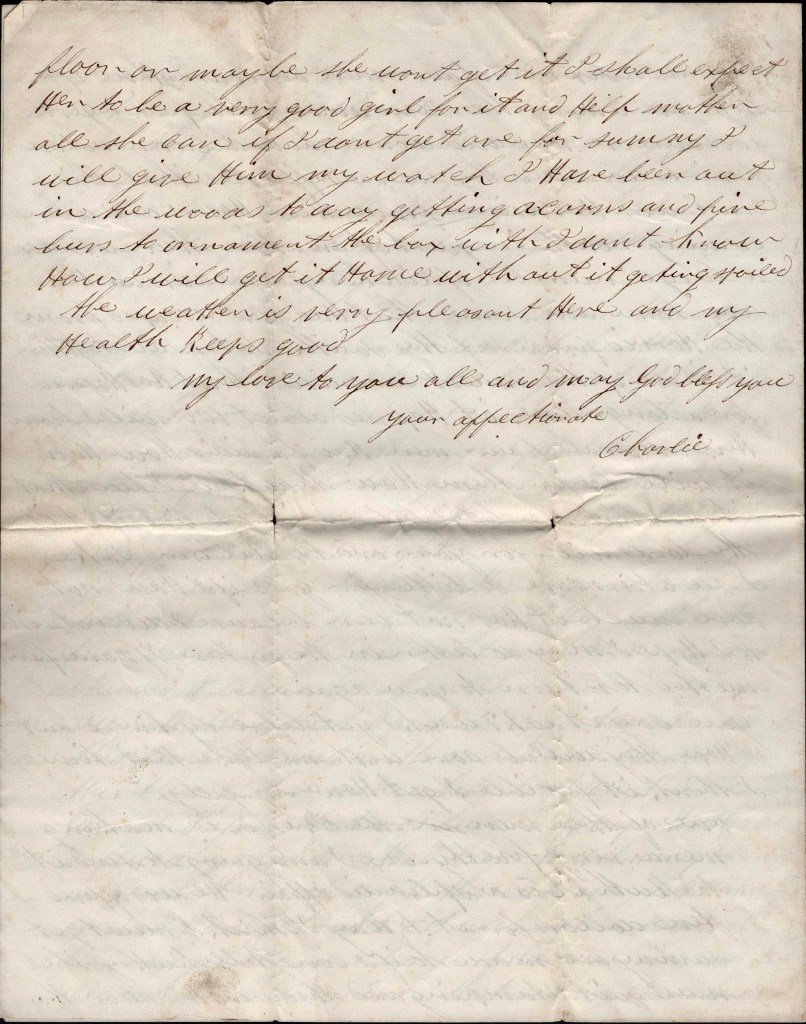

One of the men in the prison is making me a very pretty box. I am going to send it to Ruth. It is a splendid affair, He was offered ten dollars for it today. I think I must get Summy one made too if I can. Tell Ruthey she must quit stomping and throwing herself on the floor or maybe she won’t get it. I shall expect here to be a very good girl for it and help Mother all she can. If I don’t get one for Summy, I will give him my watch. I have been out in the woods today getting acorns and pine burs to ornament the box with. I don’t know how I will get it home without it getting spoiled.

The weather is very. pleasant here and my health keep good. My love to you all and may God bless you. Your affectionate, — Charlie

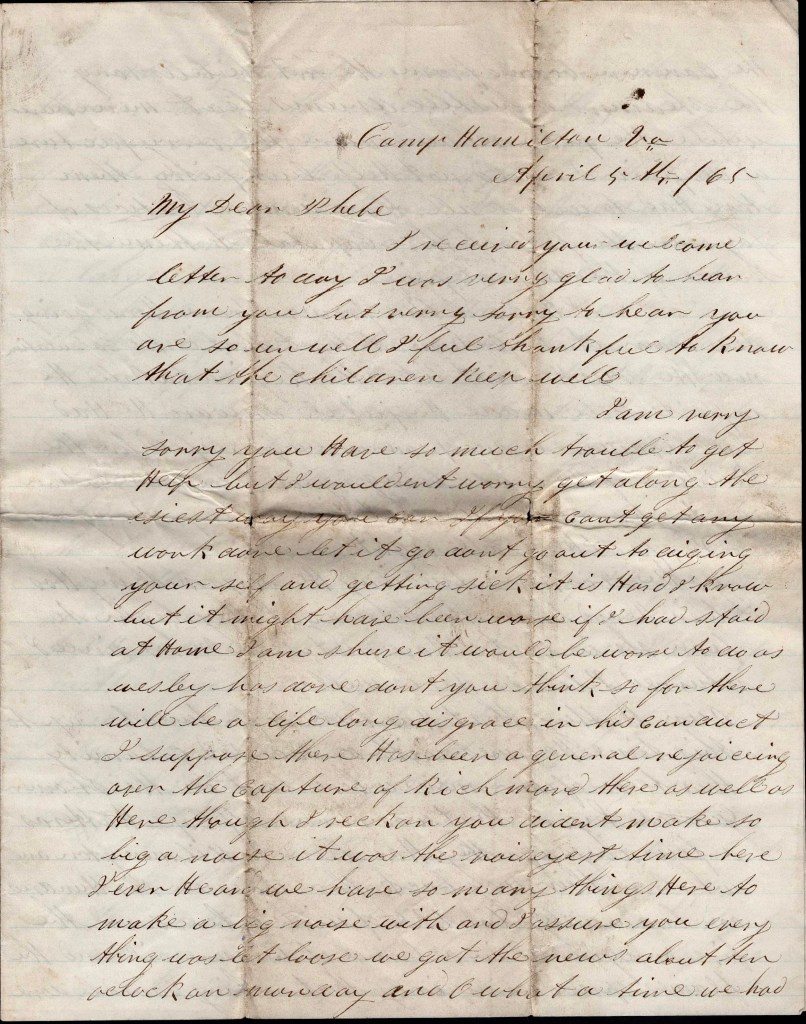

Letter 22

Camp Hamilton, Va.

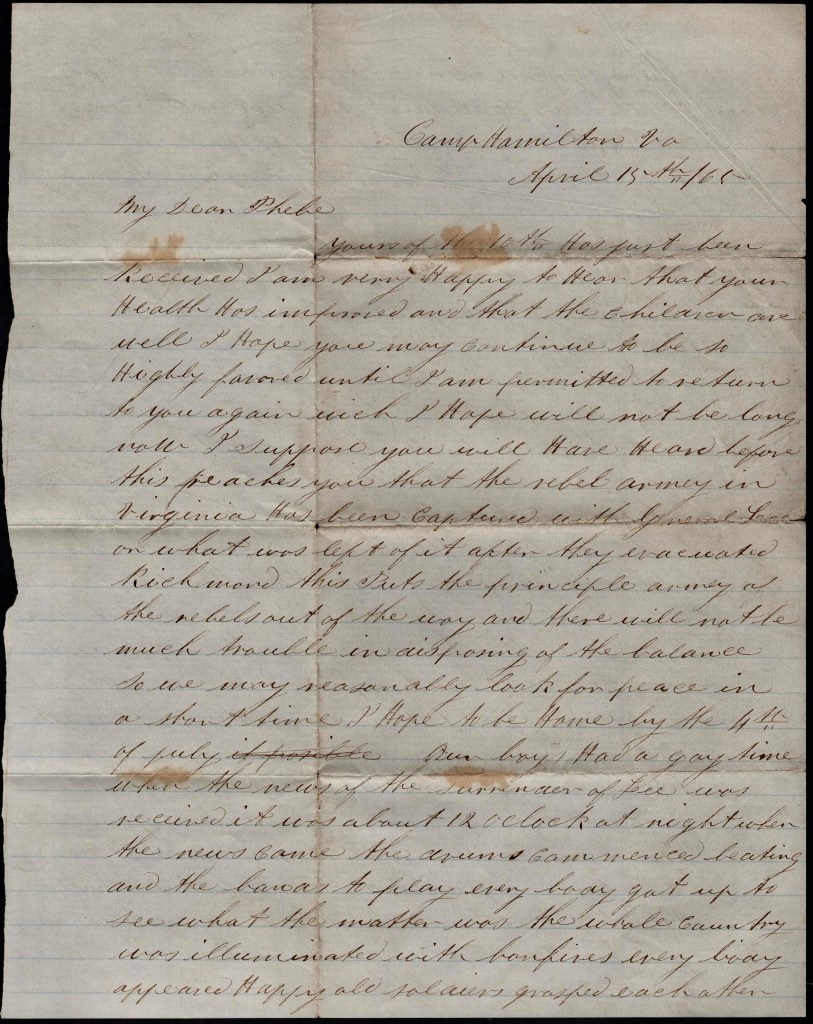

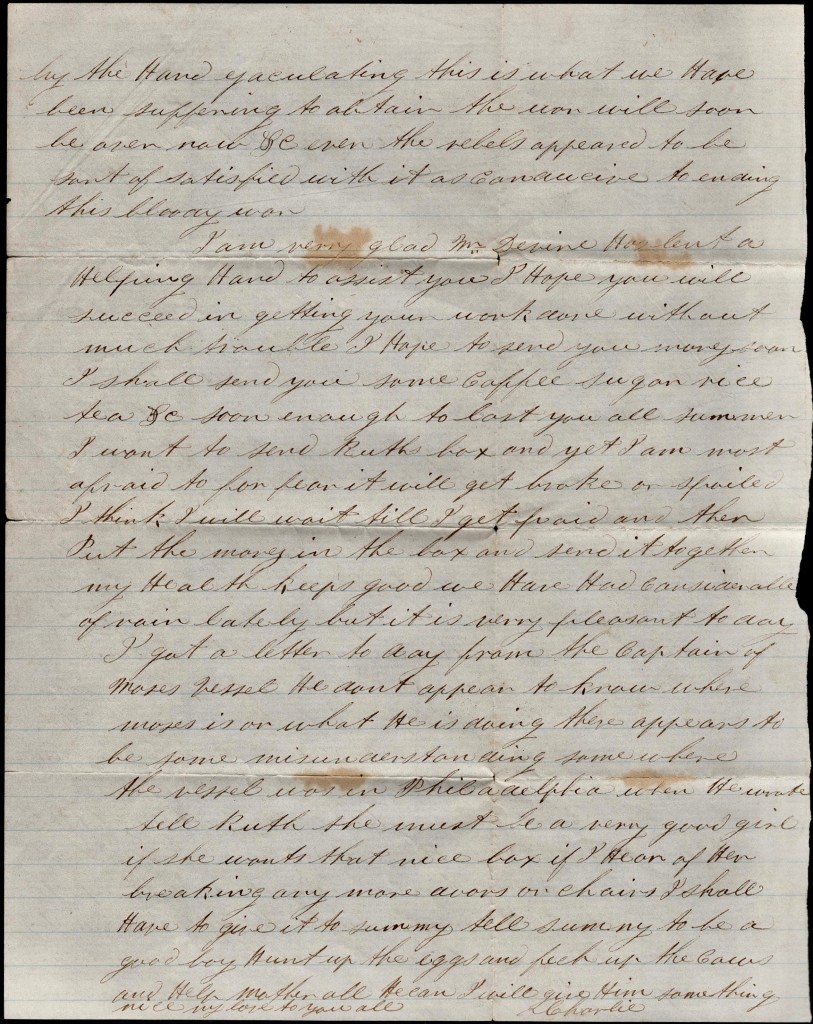

April 15, 1865

My dear Phebe,

Yours of the 10th has just been received. I am very happy to hear that your health has improved and that the children are well. I hope you may continue to be so highly favored until I am permitted to return to you again which I hope will not be long.

Well, I suppose you will have heard before this reaches you that the rebel army in Virginia has been captured with General Lee or what was left of it after they evacuated Richmond. This puts the principal army of the rebels out of the way and there will not be much trouble in disposing of the balance so we may reasonably look for peace in a short time. I hope to be home by the 4t of July.

Our boys had a gay time when the news of the surrender of Lee was received. It was about 12 o’clock at night when the news came. The drums commenced beating and the bands to play. Everybody got up to see what the matter was. The whole country was illuminated with bonfires. Everybody appeared happy. Old soldiers grasped each other by the hand ejaculating this is what we have been suffering to obtain. The war will soon be over now, &c. Even the rebels appeared to be sort of satisfied with it as conducive to ending this bloody war.

I am very glad Mr. Devine has lent a helping hand to assist you. I hope you will succeed in getting your work done without much trouble. I hope to send you money soon. I shall send you. some coffee, sugar, rice, tea &c. soon enough to last you all summer. I want to send Ruth’s box and yet I am most afraid to for fear it will get broken or spoiled. I think I will wait till I get paid and then put the money in the box and send it together. My health keeps good.

We have had considerable of rain lately but it is very pleasant today. I got a letter today from Captain of Moses’ vessel. He don’t appear to know where Noses is or what he is going. There appears to be some misunderstanding somewhere. His vessel was in Philadelphia when he wrote. Tell Ruth she must be a very good girl if she wants that nice box. If I hear of her breaking anymore doors or chairs, I shall have to give it to Summy. Tell Summy to be a good boy, hunt up the eggs, fetch up the cows, and help Mother all he can. I will give him something nice. My love to all. — Charlie