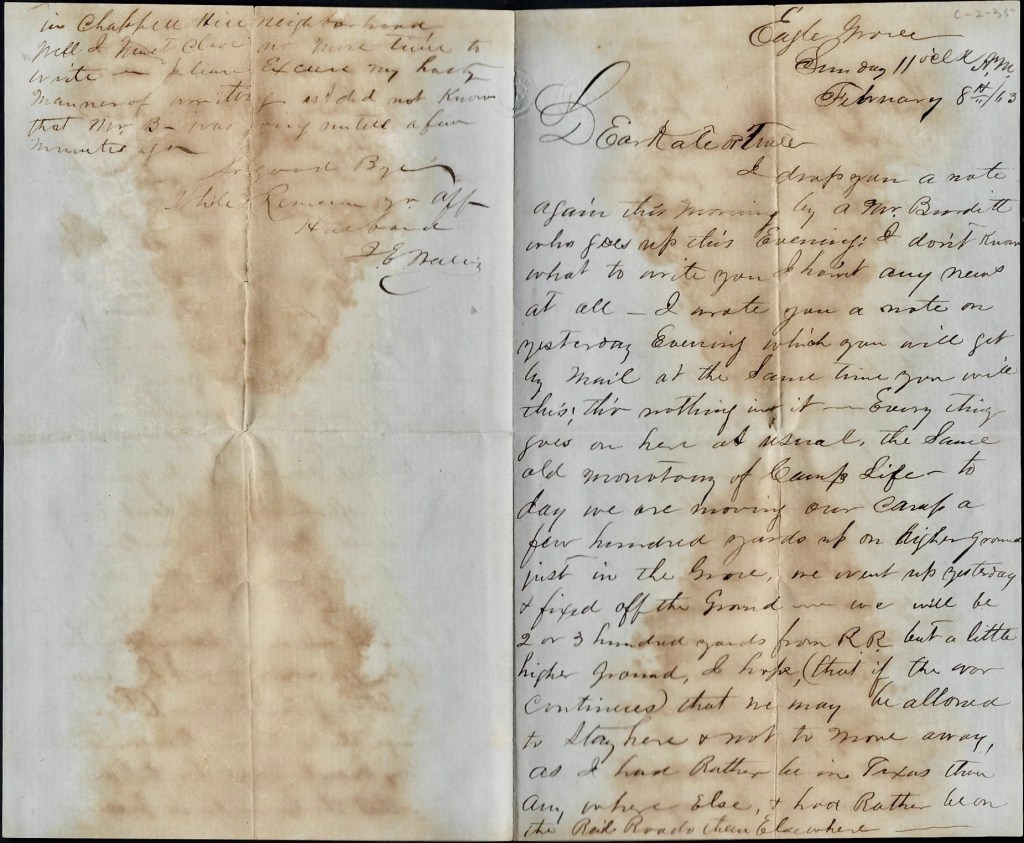

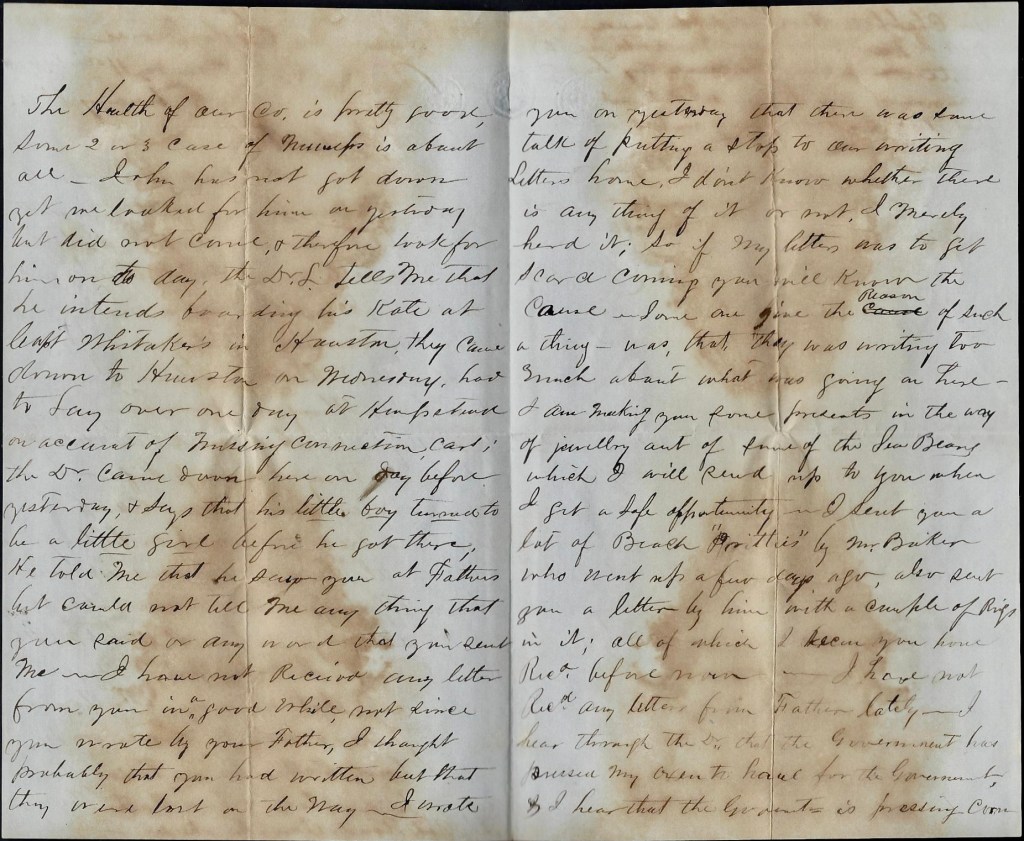

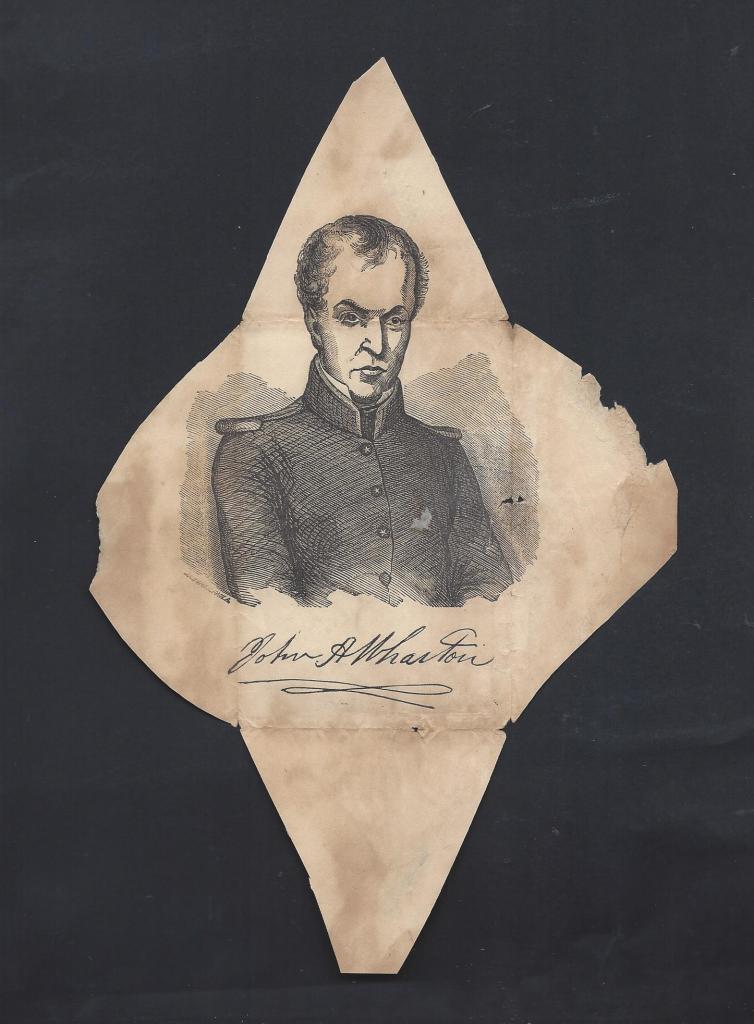

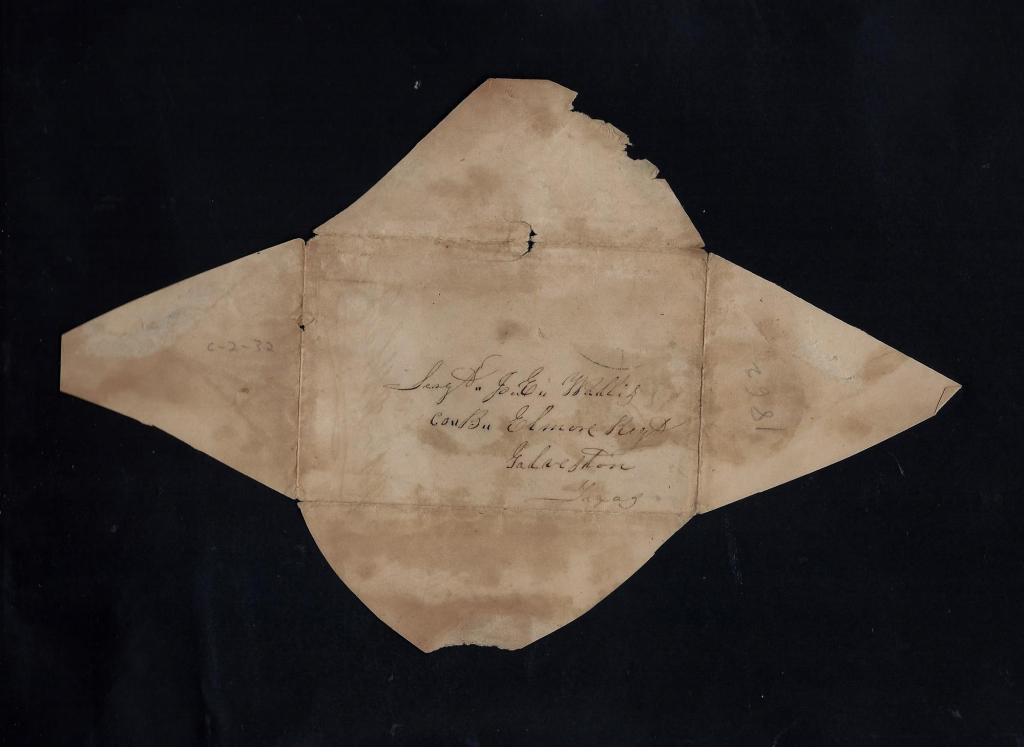

The following letter was written by 41 year-old Squire Green Sherman (1821-1869) who mustered in as a private in Capt. Claudius Buster’s Company, Elmore’s 20th Texas Infantry at Hempstead, Texas, in late April 1862. Muster rolls indicate that he enlisted in Burleson county. In January 1863 he was promoted to 2nd Sergeant of Co. C. and was later detailed as a a clerk to Gen. McCulloch’s Headquarters in Galveston and later in Houston—a situation held throughout the remainder of the war.

Sherman’s letter includes a description of the Confederate defenses at Galveston Bay in January 1863, which was blockaded by Union gunboats. “We are expecting an attack constantly & the probability is that but little resistance will be made on our part. The fact is, we cannot hold the city against their fleet, as it cannot be fortified so as to successfully defend it,” he wrote.

Sherman wrote the letter to Sarah (“Sallie”) Elizabeth Johnson (1843-1901) with whom he married in 1864 or 1865.

[Note: The family name was originally spelled Shearman.]

Transcription

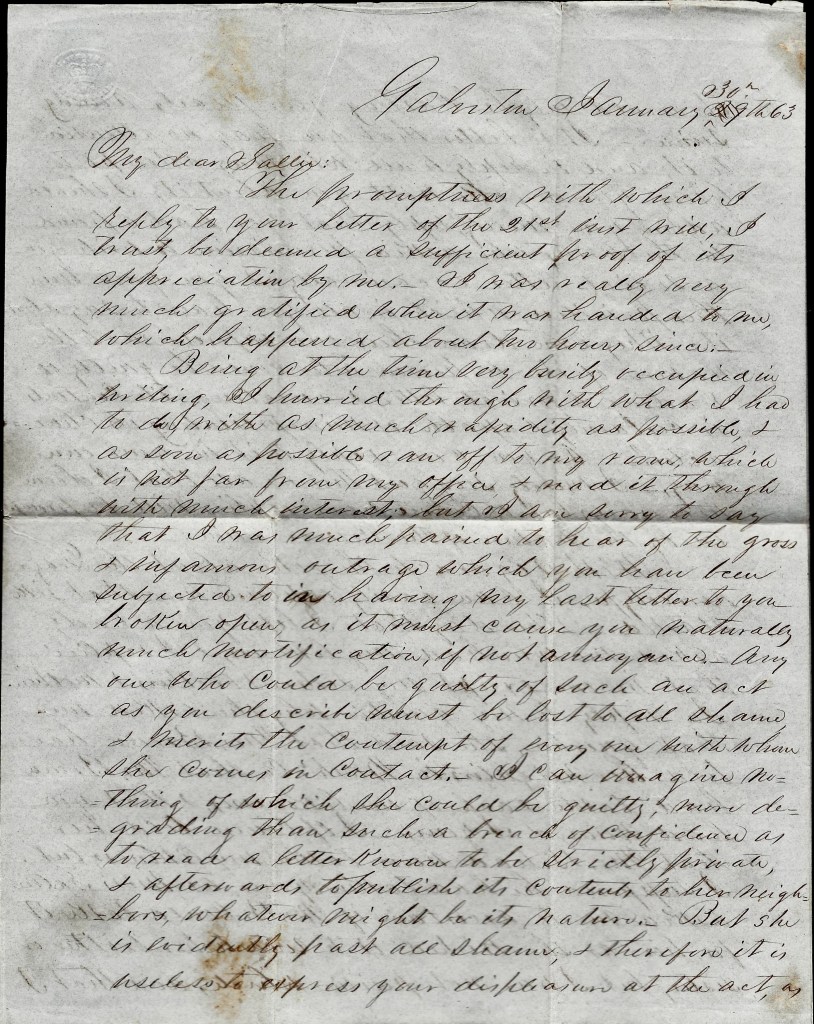

Galveston, [Texas]

January 30th 1863

My dear Sallie,

The promptness with which I reply to your letter of the 21st inst. will, I trust, be deemed a sufficient proof of its appreciation by me. I was really very much gratified when it was handed to me, which happened about two hours since.

Being at the time very busily occupied in writing, I hurried through with what I had to do with as much rapidity as possible, & as soon as possible ran off to my room which is not far from my office & read it through with much interest, but I am sorry to say that I was much pained to hear of the gross& infamous outrage which you have been subjected to in having my last letter to you broken open as it must cause you naturally much mortification, it not annoyance. Anyone who could be guilty of such an act as you describe must be lost to all shame & merits the contempt of everyone with whom she comes in contact. I can imagine nothing of which she could be guilty more degrading than such a breach of confidence as to read a letter known to be strictly private, and afterwards to publish its contents to her neighbors, whatever might be its nature. But she is evidently past all shame and therefore it is useless to express your displeasure at the act, as it would only be “casting your pearls among swine.” It is better that you pay no attention to it; and in reply to all who may attempt to quiz you or joke with you about it, I should advise you merely to reply that you had a friend in the Army who asked a permission to write you a social letter occasionally, & you gave him this privilege, which is all you have to say about it. A person who could be guilty of reading a private letter & revealing its contents is certainly capable of misrepresenting its character. Or you can reply to it in your own way. I merely suggest this as all that I deem necessary; but of course your replies will be prompted by the nature of the conversation.

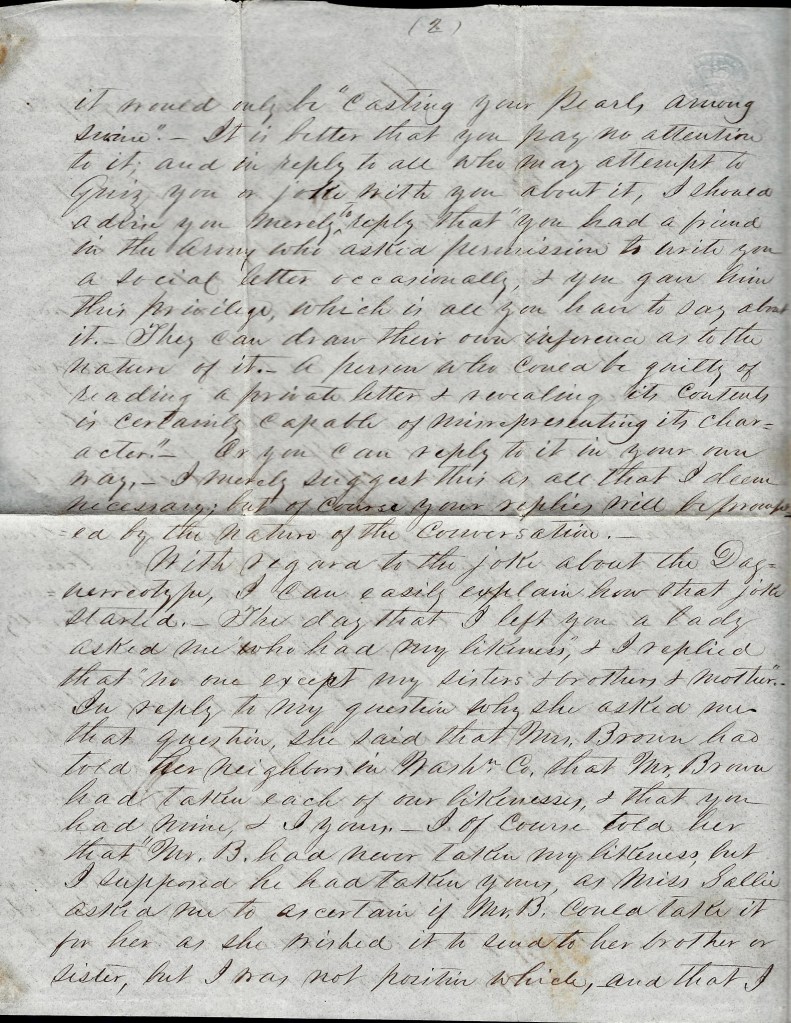

With regard to the joke about the daguerreotype, I can easily explain how that joke started. The day that I left you, a lady asked me “who had my likeness,” & I replied that no one except my sisters & brothers & mother. In reply to my question why she asked me that question, she said that Mrs. Brown had told her neighbors in Washington county that Mr. Brown had taken each of our likenesses & that you had mine, & I yours. I of course told her that “Mrs. Brown had never taken my likeness, but I supposed he had taken yours, as Miss Sallie asked me to ascertain if Mr. Brown could take it for her as she wished it to send to her brother or sister, but I was not positive which, and that I heard you afterward speak of it as having been badly taken on account of some defect in the chemicals.” I let the subject drop, after laughing at the absurd reports people would start, not even mentioning that I wait with you to get it taken. The best way is to let them talk on—it cannot hurt you, if you deem me worthy of your esteem, & are not ashamed to have me known as your affianced. I should like to know which of the Fullerton’s told about the likeness. They both love to talk, & say a great many things merely for the sake of talking. But enough of this. I have devoted already more space to it than you will consider it deserves—at least I hope so.

I had not heard of Mr. Beard’s death. I should like to hear what was the cause of it. I feel much sympathy for his large family who are left with but little means of support.

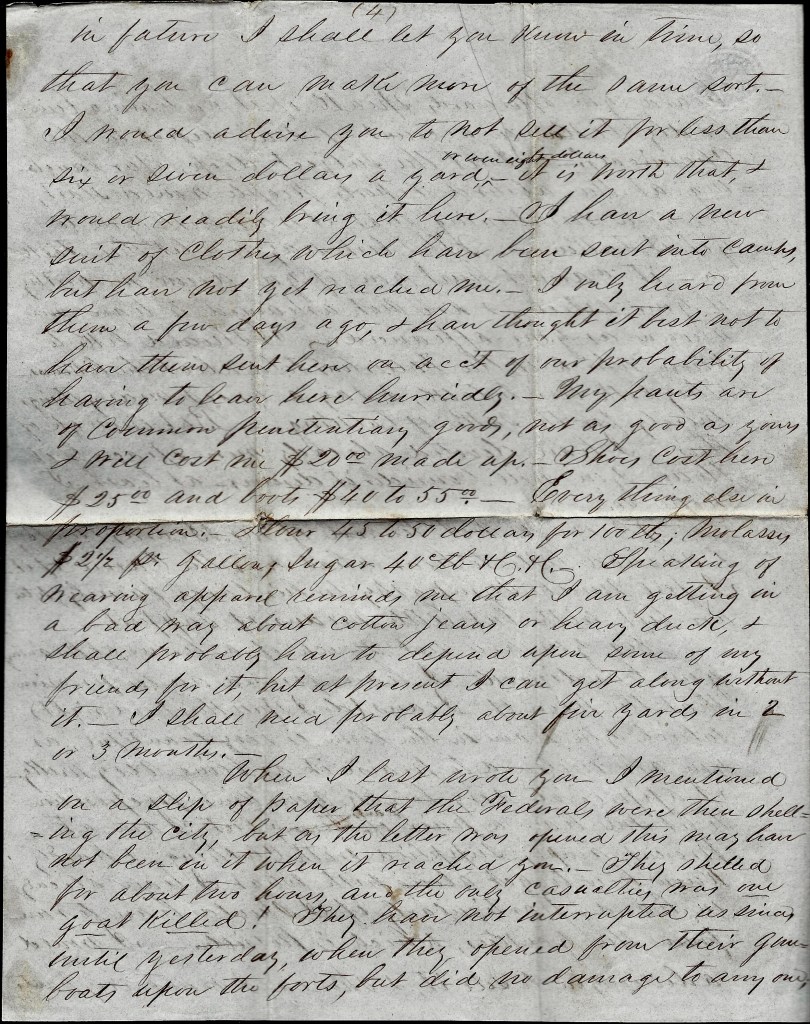

As you are not much of a hand at praising your handiwork, I have formed an impression that the piece of Jeans (do I spell this word right) which you have in the loom is very beautiful, as you are inclined to praise it as being very pretty. I appreciate very highly your kind proposition to me me have a pair of pants; but I am at present amply supplied with clothing & hardly know how to get along with what I have already on hand—particularly if I should have to run from the Yankees which is possible. I would advise you to sell it & should I want any pants in future, I shall let you know in time, so that you can make more of the same sort. I should advise you to not sell it for less than six or seven dollars a yard—or even eight dollars. It is worth that & would readily bring it here. I have a new suit of clothes which have been sent into camp but has not yet reached me. I only heard from them a few days ago & have thought it best not to have them sent here on account of our probability of having to leave here hurriedly. My pants are of common penitentiary goods, not as good as yours, & will cost me $20 made up. Shoes cost here $25 and boots $40 to 55. Everything else in proportion. Flour 45 to 50 dollars for 100 lbs., molasses $2.5 per gallon, sugar 40 cents a lb., &c. &c. Speaking of wearing apparel reminds me that I am getting in a bad way about cotton jeans or heavy duck, & shall probably have to depend upon some of my friends for it, but at present I can get along without it. I shall need probably above five yards in two or three months,

When I last wrote you I mentioned on a slip of paper that the Federals were then shelling the city, but as the letter was opened, this may have not been in it when it reached you. They shelled for about two hours and the only casualties was one goat killed! They have not interrupted us since until yesterday when they opened from their gunboats upon the forts, but did no damage to anyone. But we are expecting an attack constantly & the probability is that but little resistance will be made on our part. The fact is, we cannot hold the city against their fleet, as it cannot be fortified so as to successfully defend it. They threaten, I hear, to send “a fleet here that will teach us a lesson which we will not soon forget.” If a very large force is sent, the city will no doubt be left without resistance, as they otherwise would be enabled to claim a victory which we do not wish. Everything, however, is uncertain & what I state, of course, is only intended for you in confidence. One week may materially alter the aspect of affairs. There are now in sight four boats which are here merely to keep the city blockaded.

We have disastrous news from Vicksburg today to the effect that it has been taken by the enemy, but no particulars. Also that 8,000 of our army have been taken prisoners in Arkansas. I sincerely hope these rumors are false, but fear they are true.

You seem to constantly entertain the hope that the war will end soon, but my dear Sallie, I am sorry to say that I see things in a very different light. There is in my estimation no prospects—not the slightest—of a speedy termination of this struggle. This is only my opinion, but wait, & I doubt not you will find that I am right in these views.

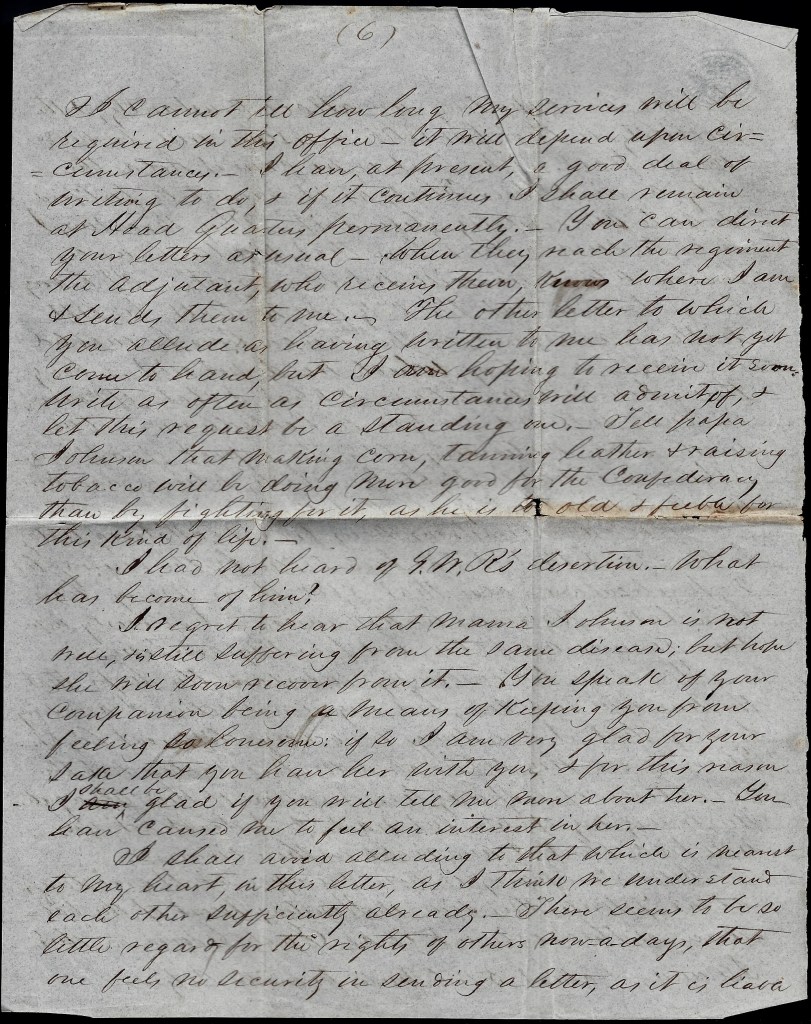

Our company is now camped at Harrisburg, about 7 miles this side of Houston; most of the balance of the regiment is at Eagle Grove on this Island, & about 5 or 6 miles from the city. I cannot tell how long my services will be required in this office. It will depend upon circumstances. I have at present a good deal of writing to do, & if it continues, I shall remain at Head Quarters permanently. You can direct your letters as usual. When they reach the regiment, the adjutant, who receives them, knows where I am and sends them to me. The other letter to which you allude as having written to me has not yet come to hand but I am hoping to receive it soon. Write as often as circumstances admit of & let this request be a standing one. Tell papa Johnson that making corn, tanning leather, & raising tobacco will be doing more good for the Confederacy than by fighting for it, as he is too old and feeble for this kind of life.

I had not heard of G. W. R’s desertion. What has become of him?

I regret to hear that mama Johnson is not well & is still suffering from the same disease; but hope she will soon recover from it. You speak of your companion being a means of keeping you from feeling so lonesome. If so, I am very glad for your sake that you have her with you, & for this reason I shall be glad if you will tell me more about her. You have caused me to feel an interest in her.

I shall avoid alluding to that which is nearest to my heart in this letter as I think we understand each other sufficiently already. There seems to be so little regard for the rights of others now-a-days, that one feels no security in sending a letter, as it is liable [remainder of letter missing]