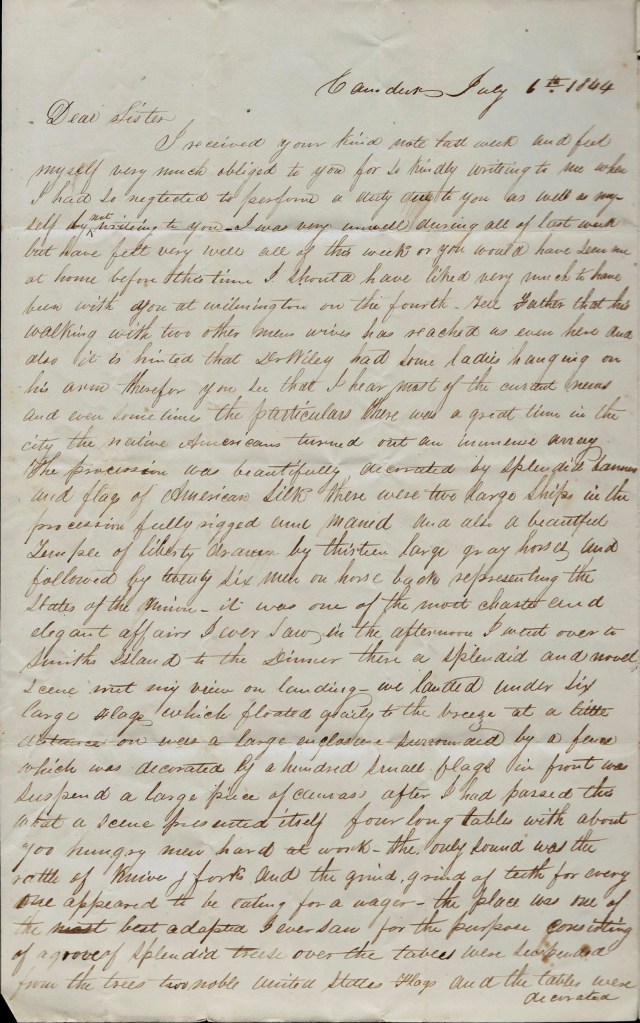

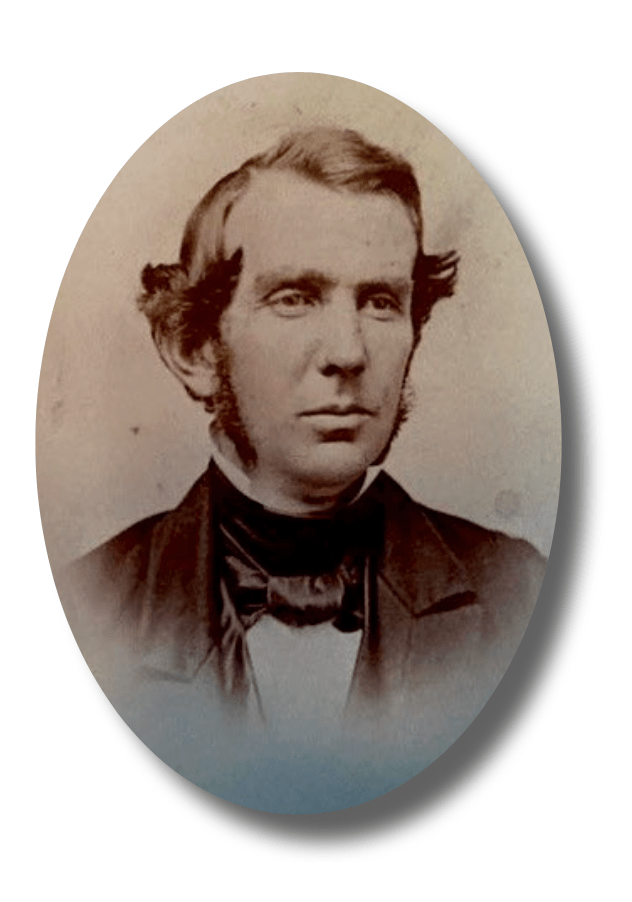

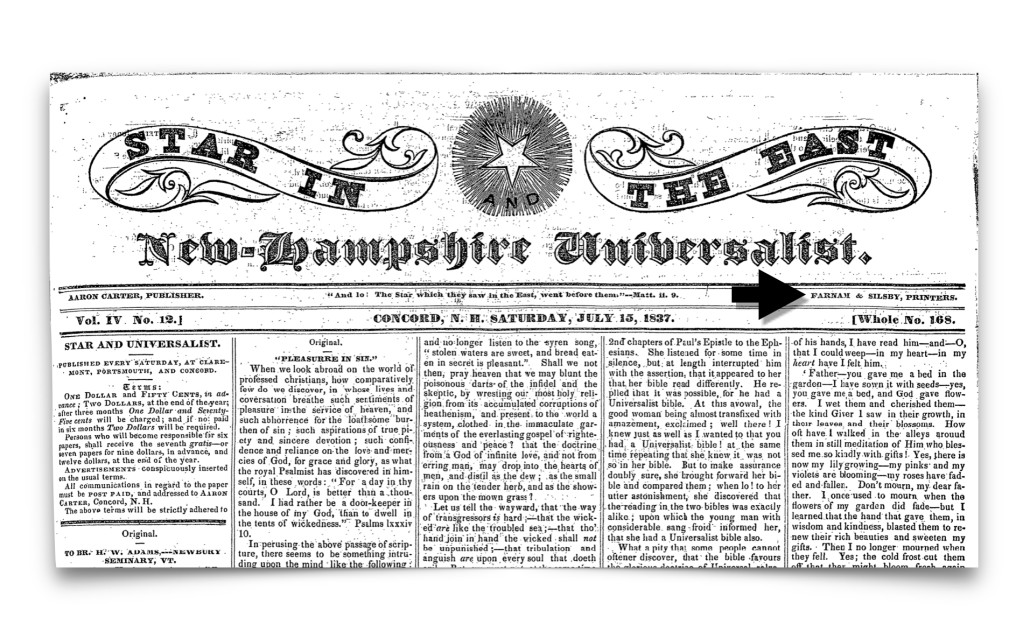

The following letter was written by Henry Simpson Mesinger Farnam (1815-1878), the son of Roger and Susan (Everett) Farnam of Attleboro, Massachusetts. Henry wrote the letter to his friend, George Henry Hough Silsby (1817-1892), the son of Ozias and Francis (Jones) Silsby of Hillsboro county, New Hampshire. We learn from the letter that Henry and George were former partners in the publication, “Star in the East“—a religious newspaper out of Concord, New Hampshire. The letter was written in the midst of the financial depression that occurred in 1837 so my assumption is that the newspaper failed as did many small businesses at that time.

From what little I could find on both young men, George remained in Concord all of his life. He ran for the position of town clerk in Concord, N. H. in 1849 but was defeated. In the 1850s he was a partner in the printing firm of Morrill & Silsby on Main Street in Concord. George was a stationer, printer, and bookbinder, and followed that business during the active period of his life.

Henry left Concord and attempted to earn a living in the District of Columbia, in New York City in the early 1840s. He may have been the same Henry S. M. Farnam (Farnam & Osgood) groceries and dry goods, who was listed in the 1867 Concord, New Hampshire.

Henry’s letter is a tantalizing treasure trove of historical tidbits delving into the social and political scene of the District of Columbia in the late 1830s. Within its pages, he regales us with colorful depictions of Henry Clay, James Buchanan, and John Quincy Adams, shedding light on the excessive alcohol consumption among Congressmen and the proliferation of brothels in the city.

Transcription

Washington D. C.

April 23, 1838

Friend Silsby,

“God bless you!” is just such a salutation as I should greet you with were I to meet you in person or perhaps might “run in this wise”—“God bless you, Squire, give us your hand.” But as it would be useless and vain for me to add the request here, I will content myself with invoking the blessing.

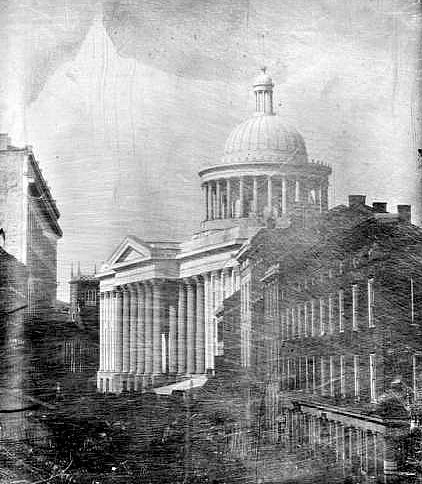

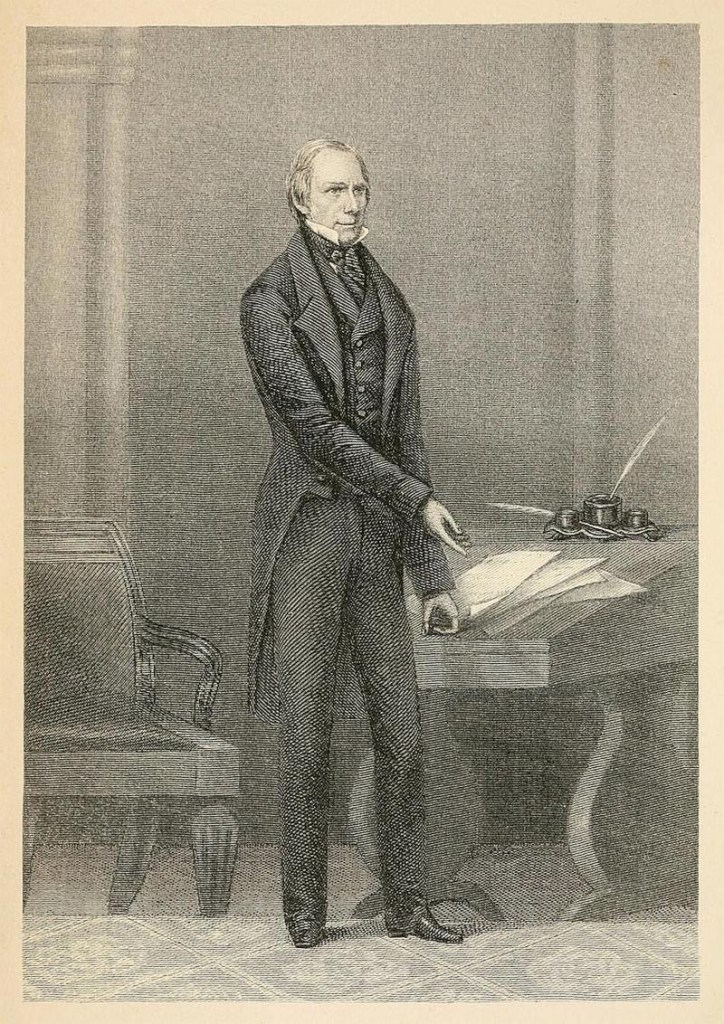

I am on a furlough this afternoon which you know is a very desirable respite to a jour[neyman] printer—especially when he has the consolation of knowing when Saturday night comes round that he shall find his bill docked at the rate of 20 cents per hour during his absence. But I shall be called on duty again tomorrow morning, while three poor devils received the gratifying intelligence when they come into the office this morning that that their services were no longer required. Four of us were furloughed for this afternoon only, one of whom concluded that it would be a good time to take a “round turn” as they call it here—what we at the North usually call a “bust“—and he has probably arrived at the corner and capsized before this; while two others and myself took a “B-line” for the Capitol where we hear Henry Clay make one of his best speeches, a short one however, and a reply to it from Buchanan of Pennsylvania. Clay is a noble-looking fellow, and his eloquence when speaking exceeds all the lofty opinions I had ever formed of it from what I had read and heard of his greatness as an orator and debater. the likeness in his biography, which you have seen, is a good one. Buchanan too is one of the finest speakers in the Senate. I have heard the most of the distinguished men in the Senate speak a few minutes each, and some of the most talented ones in the House. 1

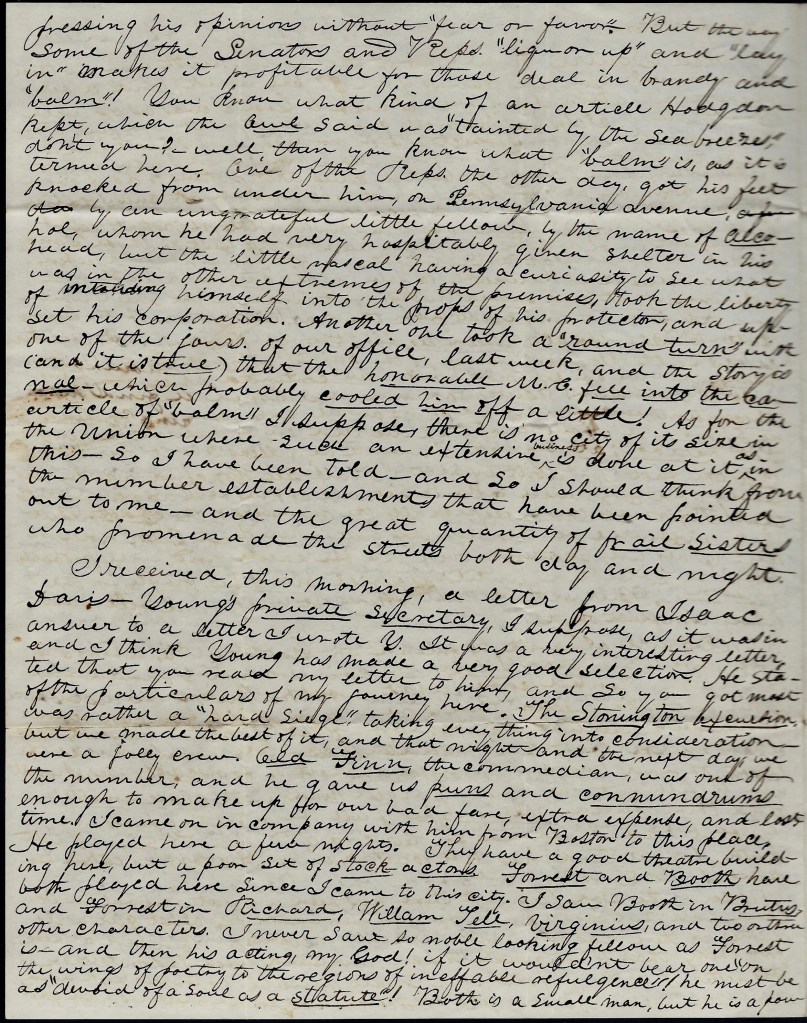

I went into the House a few moments this afternoon. Old Johnny Q. [John Quincy Adams] had the floor, and, as usual, expressing his opinions without “fear or favor.” But the way some of the Senators and Reps. “liquor up” and “lay in” makes it profitable for those [who] deal in brandy and “balm!” You know what kind of an article Hodgdon kept, which the owl said was “tainted by the sea breezes,” don’t you? Well then you know what “balm” is, as it is termed here.

One of the Reps. the other day got his feet knocked from under him on Pennsylvania Avenue by an ungrateful little fellow by the name of alcohol whom he had very hospitably given shelter in his head, but the little rascal having a curiosity to see what was in the other extremes of the premises took the liberty of intruding himself into the props of his protector, and upset his corporation. Another one took a “round turn” with one of the jours. of our office last week and the story is (and it is true) that the honorable M. C. fell into the canal which probably cooled him off a little! As for the article of “balm”, I suppose there is no city of its size in the Union where such an extensive business is done at it as in this—so I have been told—and so I should think from the number [of] establishments that have been pointed out to me—and the great quantity of frail sisters who promenade the streets both day and night.

I received this morning a letter from Isaac Davis—Young’s private secretary, I suppose, as it was in answer to a letter I wrote Young. It was a very interesting letter and I think Young has made a very good selection. He stated that you read my letter to him and so you got most of the particulars of my journey here. The Stonington Excursion was rather a “hard siege” taking everything into consideration but we made the best of it and that night and the next day we were a jolly crew. Old Finn, the comedian, was one of the number, and he gave us puns and conundrums enough to make up for our bad fare, extra expense, and lost time. I came on in company with him from Boston to this place. He played here a few nights.

They have a good theater building here but a poor set of stock actors. Forrest and Booth have both played here since I came to this city, I saw Booth in Brutus and Forrest in Richard, William Tell, Virginians, and two or three other characters. I never saw so noble-looking fellow as Forrest is—and then his acting, my God! if it wouldn’t bear one “on the wings of poetry to the regions of ineffable refulgence!” He must be as “devoid of soul as a statue!” Booth is a small man but he is a powerful actor.

Well, Squire, how “wags the world” with you in these hard times? You are having you $7 per week and a permanent situation, I suppose. I wish to God I was as well off. It is true, I am having pretty good wages just now, but then in a month from now. I expect to be on my oars when I shall have to make tracks for some other region and spend what I have earned in traveling and lounging about in cities with nothing to do. A good cit. [situation] in Concord at 7 per week is not to be sneered at and I advise all who have got such an [one] to hold on to it as long as they can.

The blues crawl over me sometimes when I think of the pleasant days I have spent in Old Concord, and among the best of those I may reckon my sojourn at the “Star” office, with you as a comp[anion], when our names went forth weekly to give character and influence to the important and sacred truths contained in the sheet which bore them; scattering light from the darkest corners of the Grany State, to “Bluffsdale, Green county, Illinois”—the residence of that believer “in the faith and delivered to the Saints,” Abram Coon!! 1 It is strange that we could not have been contented while enjoying such a distinction! But man is never satisfied, you now, until contentment would be of no avail, and then he only thinks he should be. However, I think we did enjoy ourselves during that period; at any rate, I would be willing to try it over again. But the fact is, I don’t expect I shall see Concord again very soon, but I should like to see all of the old acquaintances that I formed there—especially the members of the craft. But that never will be “this side of the gate whereof St. Peter holds the key.” They are scattered over the earth and will probably never be collected until Gabriel blows his bugle for the last time. But without any joking, it akes me feel melancholy to reflect on it.

Squire, I haven’t a friend on God’s earth whom I would give more to see than Silsby! If you were here, I should feel perfectly contented, come what would. But as that is altogether out of the question, there is one way in which you can render me a very essential service—and that is—as you cannot “shed upon me the light of countenance“—-to “shed upon me the light of your mind,” through a sheet of foolscap! Yes, I want you to fill out one of the largest kind, with close matter, and thin-spaced (minion type) of all the interesting events, &c. that have transpired in Concord and vicinity since I left. Winter, I understand, has left Barton’s and Foster has taken his place. What was the trouble?

I see by the Bap[tist] Reg[ister] that there has been a great revival in Concord, and that great numbers have been added, &c. Just give us the names, if there has been any remarkable instances. There are at least forty things that I intended to have mentioned when I commenced this letter I have forgotten. I shall probably go to New York when I am out here and if I don’t get work there, I don’t know whether I shall go to Boston or to the West! Oh, by the way, I received a letter from Sherman the other day. He says he is in the paper-making business yet. Fisher is with him. He didn’t say whether they were in the money-making business or not. Tell Isaac that I will endeavor to answer his letter before long. Tell Elder Morse if he goes to New York to let me know it.

Now Squire, I want you to answer this without delay. Don’t be afraid of exposing your penmanship to my criticisms, although it may not bear a comparison with mine!! Give my respects to all who recollect me. I must wind up by subscribing myself your everlasting friend, “in the bonds of the gospel” — H. S. M. Farnam

P. S. I dare not read this over, and, shall have you to correct the errors. I will endeavor to a more interesting next time, that after I receive one from you which I shall expect soon. I suppose you are freezing in New Hampshire yet. We have had it hot enough to “scorch a feather”—peach trees blossomed a week ago. We have pretty good living here—poultry a plenty of it, from turkeys down to robins, blue birds, and even yellow birds—four to the mouthful. Possums too brought into market every morning! Oh, I’ve left off chewing tobacco–[ ] today! and take but 3 glasses of ale a day! — H. S. M. F.

1 In 1837, Henry Clay was hard at work in a successful effort to organize and strengthen the new Whig party. In his attempt to provide for it an ideological core, he emphasized restoration of the Bank of the United States, distribution of the treasury surplus to the states, continued adherence to his Compromise Tariff Act of 1833, and federal funding of internal improvements. The achievement of these goals, Clay reasoned, would mitigate the severe impact of the Depression of 1837 and sweep the Whigs into the White House in 1840. A review of the newspapers at the time of this letter suggests Clay’s speech probably had something to do with the distribution of the treasury surplus.

2 Abraham Coon (1810-1885) was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.