The following letter was written by Wealthy Ann (Winchester) Anthony (1819-1886), the wife of Pvt. Francis Preceptor Anthony (1809-1884) of Co. L, 8th New York Heavy Artillery. 53 year-old Preceptor was working as a carpenter in Attica, Wyoming county, New York at the time of the 1860 US Census. The family must have relocated to Baltimore early in the Civil War, however, as Emily datelined her letter from Baltimore and the couple were enumerated there in subsequent census records. Preceptor began his service in Co. A, 105th New York Infantry but was discharged in February 1863 for disability. The 8th New York Heavy Artillery manned the Baltimore defenses; companies L & M joining the regiment in February 1864. In May 1864, the regiment was ordered to join the Army of the Potomac in the Overland Campaign and my hunch is that many members of the company left clothing and other unnecessary articles at the Anthony residence in Baltimore for safekeeping before going to the front.

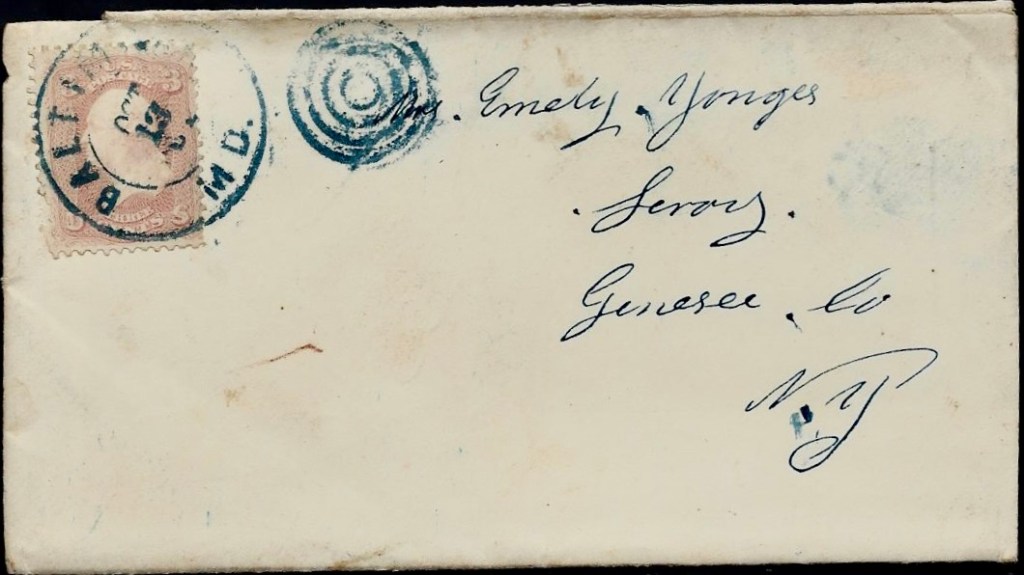

The letter was directed to Emily (Seevey) Youngs (1823-1883), the wife of Isaac Youngs (1817-1904), of Le Roy, Genesee county, New York. Emily’s oldest child, Charles J. Youngs (1844-1864) enlisted on 4 January 1864 as a private in Co. L, 8th New York Heavy Artillery, but became ill in before Petersburg and was sent to a Washington hospital where he died on 3 August 1864.

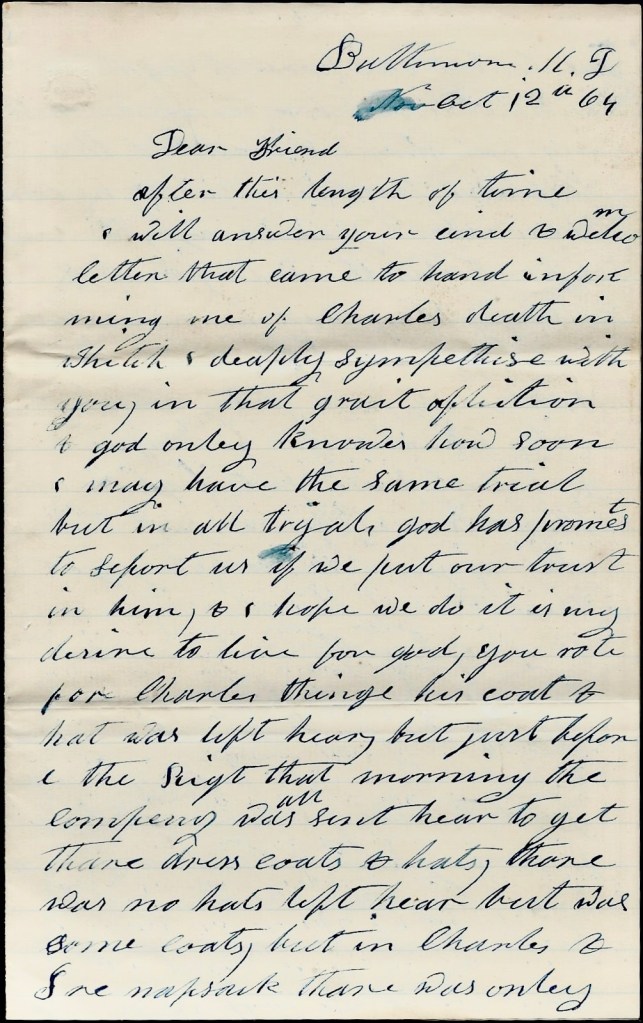

Transcription

Baltimore, Maryland

October 12, 1864

Dear Friend.

After this length of time, I will answer yours and Deliom’s letter that came to hand informing me of Charles’ death in which I deeply sympathize with you in that great affliction. God only knows how soon I may have the same trials. God has promised to support us if we put our trust in Him & I hope we do. It is my desire to live for God.

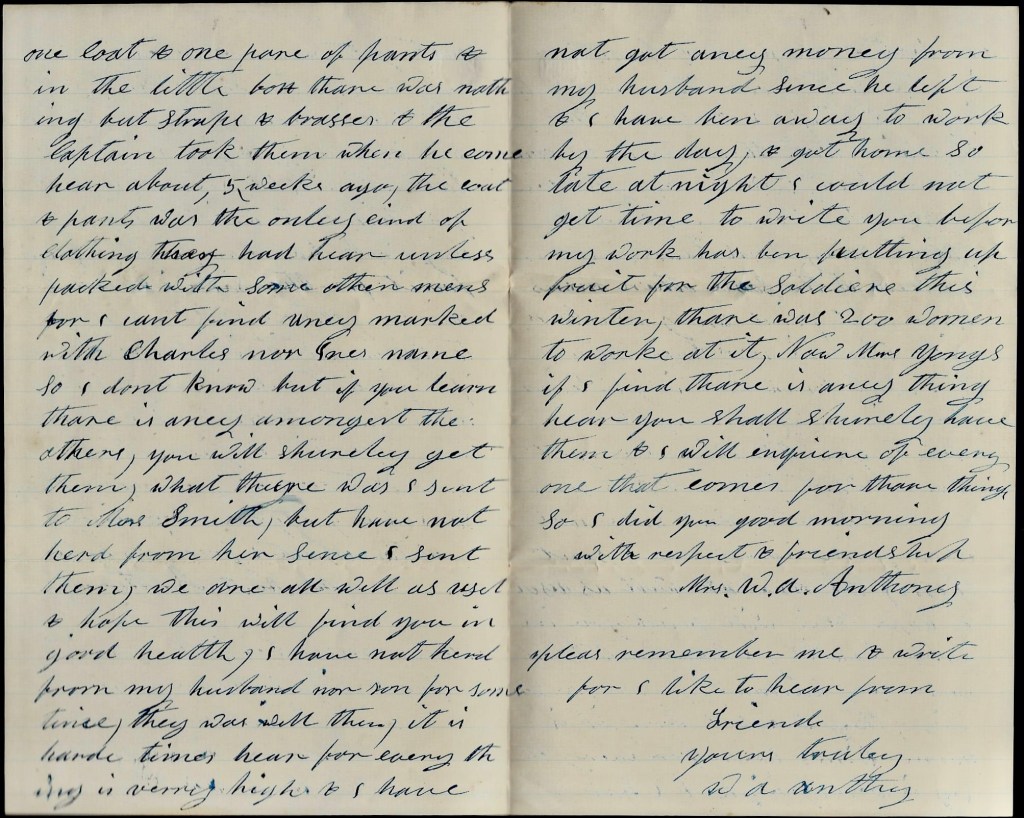

You wrote for Charles’ things—his coat that was left here, but just before the regiment [left] that morning, the company was sent here to get their dress coats & hats. There was no hats left here but was some coats. But in Charles’ knapsack there was only one coat and one pair of pants. And in the little box there was nothing but straps and brasses and the Captain took them when he come here about 5 weeks ago. The coat & pants was the only kind of clothing they had here unless packed with some other mens for I can’t find any marked with Charles’ nor other name so I don’t know. But if you learn there is any amongst the others, you will surely get them. What there was I sent to Mrs. Smith but have not heard from her since I sent them.

We are all well as usual & hope this will find you in good health. I have not heard from my husband nor son for some time. They was well then. It is hard times here for everything is very high & I have not got any money from my husband since he left. I have been away to work by the day & got home so late at night I could not get time to write you before. My work has been putting up fruit for the soldiers this winter. There was 200 women to work at it. Now, Mrs. Youngs, if I find there is anything here, you shall surely have them & I will enquire of everyone that comes for their things. So I bid you good morning with respect & friendship, — Mrs. W. A. Anthony

Please remember me & write for I like to hear from friends. yours truly, — W. A. Anthony