This letter was written by Francis (“Frank”) Markoe (1801-1872), the son of Francis and Sally (Caldwell) Markoe. Following his graduation from Middlebury College in 1823, Markoe studied law in the law office of John Sergeant in Philadelphia and practiced for two years. He then entered government service (1832-1861) serving as Chief, U.S. Consular Bureau and then in the Diplomatic Bureau. He married Mary Galloway Maxey in 1834. He died in Baltimore, Maryland.

An interesting vignette concerning Markoe involves his candidacy for the position as Secretary of the new Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C. in 1846. The following was said of Markoe:

In his mid-forties, Markoe was a clerk in the Diplomatic Bureau of the State Department, as well as the corresponding secretary of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, an organization based in Washington and founded with the hope of receiving the Smithson bequest to establish a national museum. Markoe had a botanical collection and was recognized as a mineralogist of some ability. But his most important qualification for the position of secretary was his extensive political connections. He claimed President James K. Polk, as well as current and former members of Congress and cabinet members, among his supporters. His selection would be a sign that the secretaryship was a post to be awarded on the basis of political patronage.

Markoe didn’t get the selection, however. He was passed over for Joseph Henry, a professor of natural philosophy & physics at the College of New Jersey.

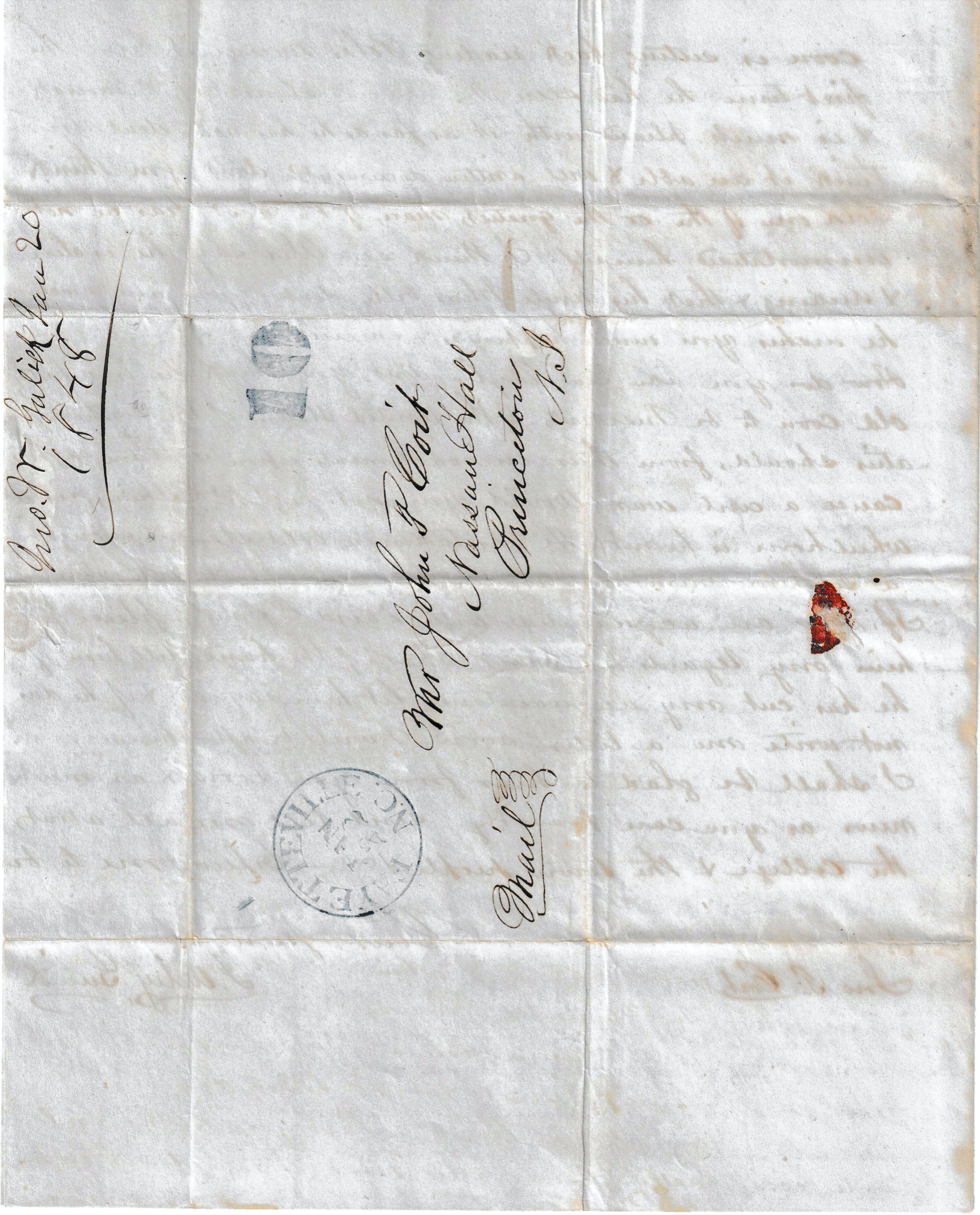

Frank wrote the letter to James McHenry Boyd. He was the first husband of Anna Eliza Boyd Barnard (nee Hall). He is mentioned by Fanny Adeline Seward in her 1862-1863 diary as “the groom” when she recounts the unfortunate story of his brief marriage: “the very day of her [Anna Barnard’s] wedding day, while on their tour, the couple stopped at a hotel, in Philadelphia, I believe. Both were preparing for dinner when the groom was stooping over his open trunk and a loaded pistol there went off and killed him!” Boyd died in December 1847.

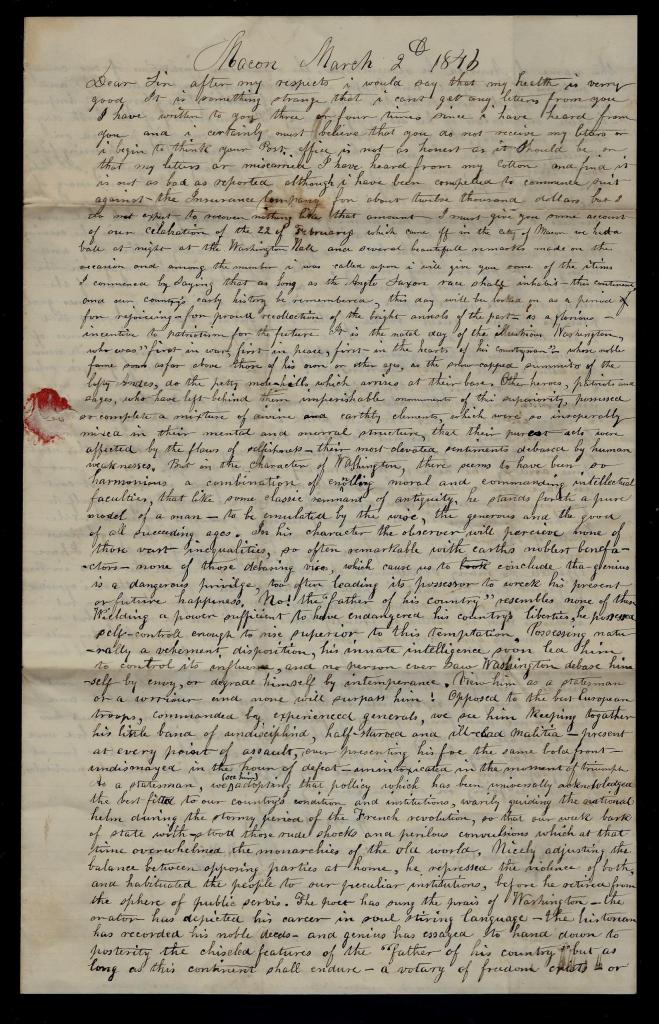

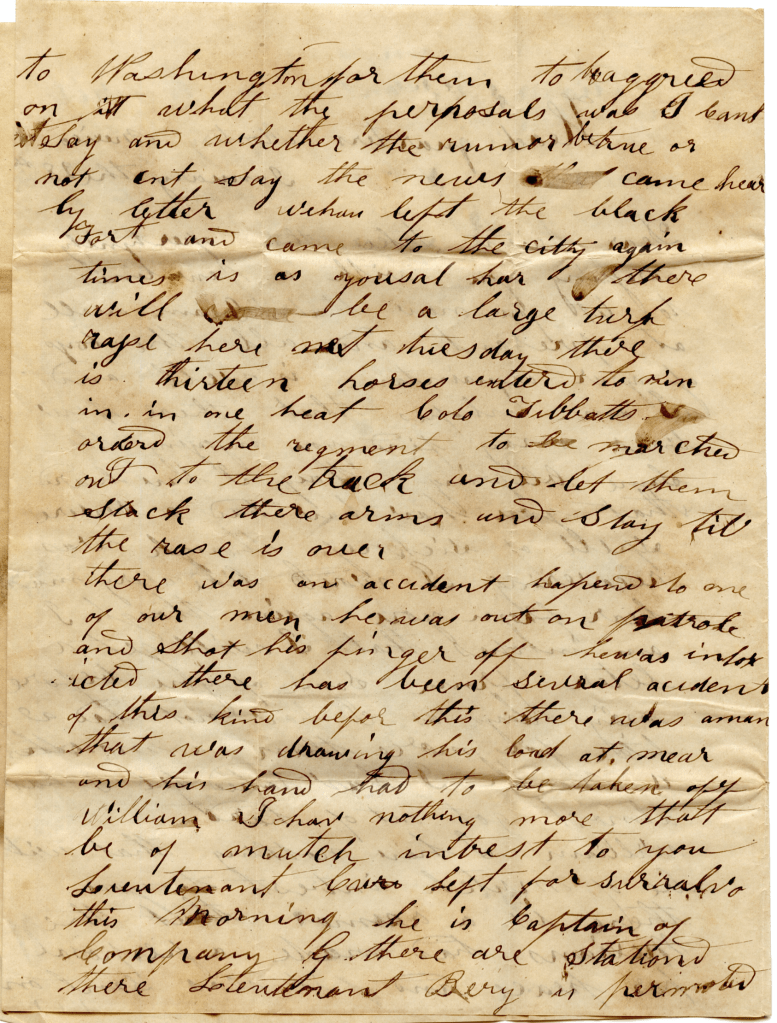

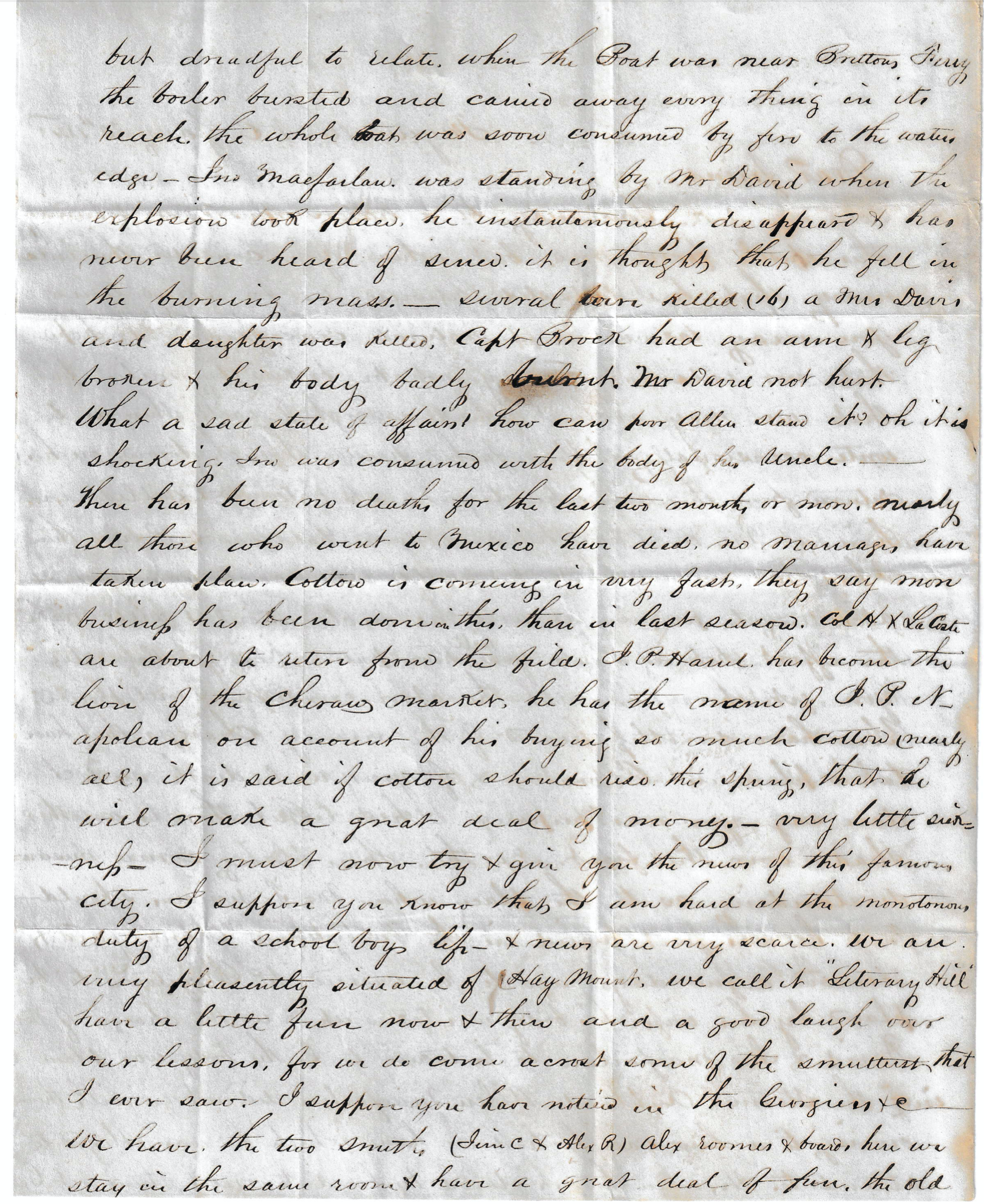

Transcription

Washington [D. C.]

21 May 1847

Mary & my father got here last night. They propose to go to W. River next Tuesday by railroad to Annapolis.

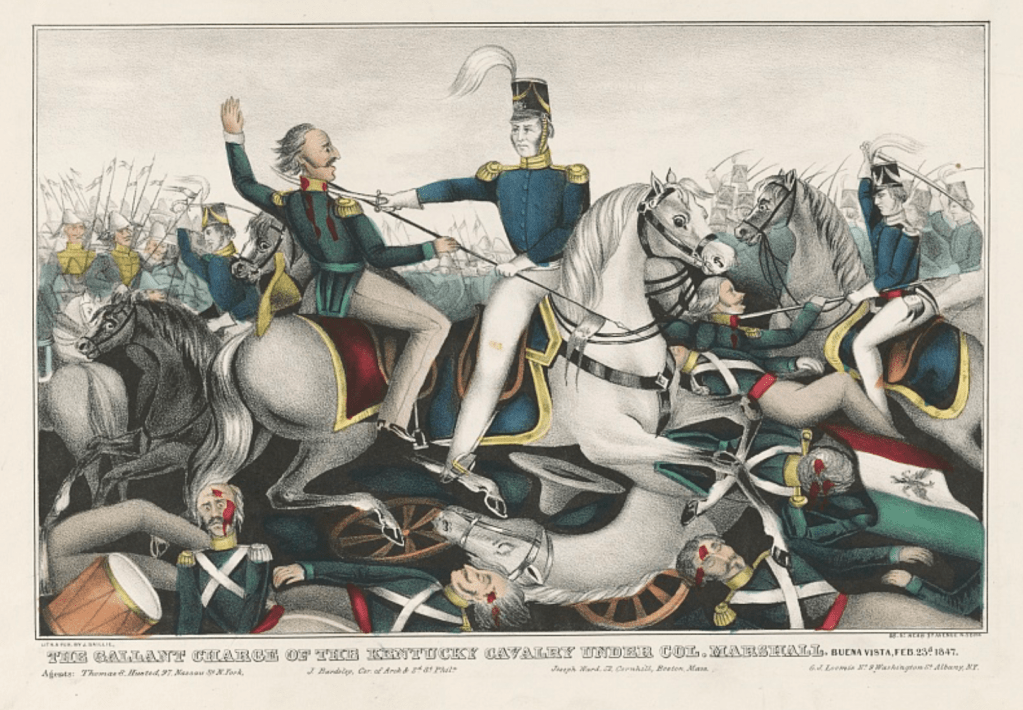

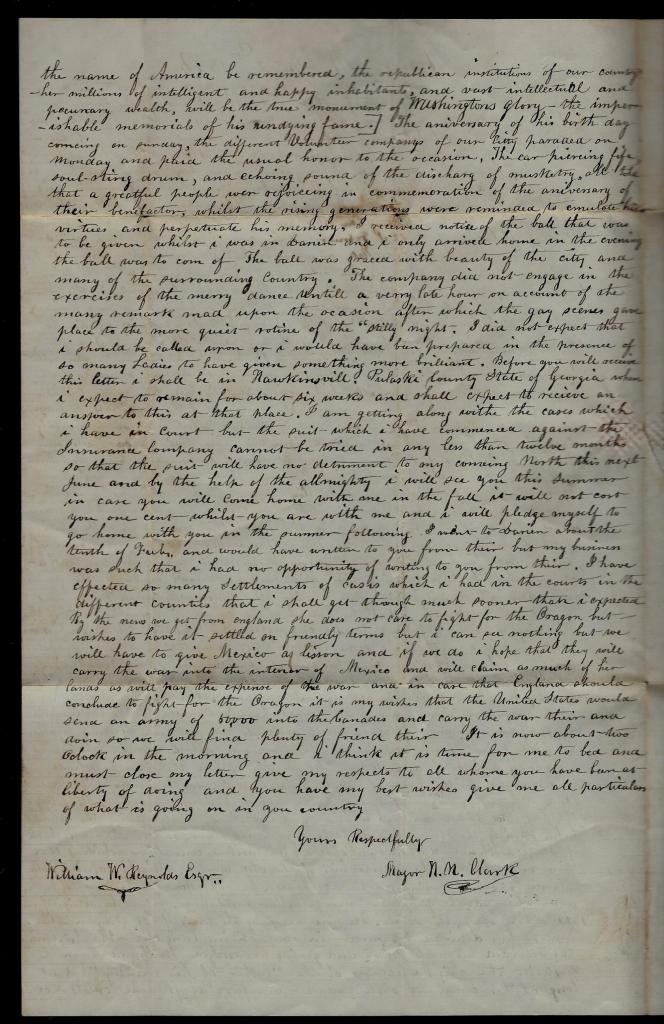

[George W.] Hughes 1 reached Washington Monday night last, stayed Tuesday & started for W. K. Wednesday morning. He will be back most likely next week, middle or end. My chief object in writing to you now is to impart a kind of secret which you may revolve in your own mind in connection with any remaining ambition you may have on the subject of going to Mexico. The President & [Secretary] Marcy have expressed a wish that he would take command of the Battalion that C. L. Jones expected to command but which was never intended to be given him. Hughes is willing to take it as Lt. Col., drill the body severely here for some time, & then proceed with them by [ ]. I spoke to him of you and he will be charmed if you will go with him. So you must see him as soon as you can. I let you know when he arrives here unless you choose to go down to W. River.

I was aware that something of the sort was in prospect before Hughes returned. When he returned he told me of it & desired me to say nothing about it because he meant to leave it to the President & Marcy to fix it their own way, but I spoke to him in reference to you immediately. Now, however, I think the matter will be generally known because this morning Major Scott, the Navy Agent, told me all about it as a thing known at the Department among many officers and I thought it well to drop you a line.

Hughes was carried to the field of battle Cerro Gordo in an ambulance & lifted into the saddle so he saw all & had a fair chance of being shot, as he was talking to General Scott when a ball knocked off a mule’s head close by them.

Henry, this letter writing is so unsatisfactory compared with talking. So find your way here somehow or other soon. I hope your knee is better. What do you hear from James & how is he? I got a letter two days ago from Ramsey in answer to the papers, &c. I sent him some time ago. He repeats your monstrous notion about the [ ] being Principles.

In haste. Affectionately yours, — Francis Markoe, Jr.

P. S. If you have any Revolutionary autographs, or such as you may have got in Europe & England [ ] may bring or send me some.

I. McH Boyd, Esq.

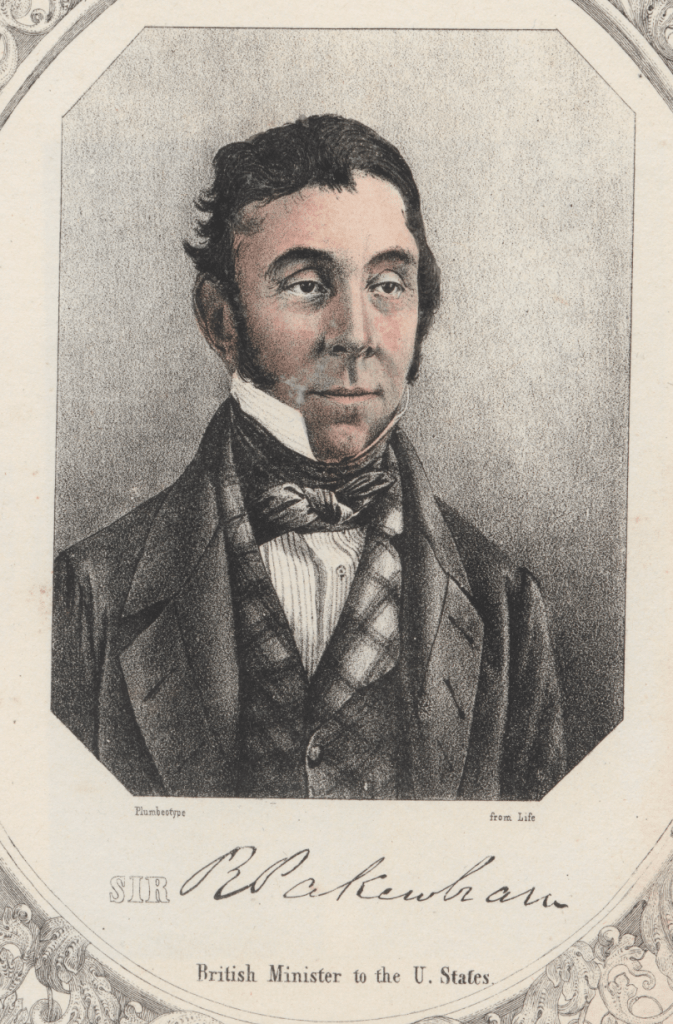

I have opened this letter to say that Mr. [Richard] Pakenham has just called in at my office to pay his final adieu. He goes to Baltimore tomorrow and says he will make it a point to see you & will inquire of your whereabouts from W. McLane whom he will see. He takes with him all our best feeling & wishes & hopes for a return to this country. Has leave of absence for two years & expects to return & will no doubt, unless promoted to some higher post.

1 George Wurtz Hughes (1806-1870) attended the United States Military Academy at West Point from 1823 to 1827, having been appointed by Caleb Baker, but was not commissioned and instead became a civil engineer in New York City. In 1829, Hughes began to work for the New York State Canal Commission. Hughes was appointed to the United States Army on July 7, 1838, as captain of Topographical Engineers. In 1840, he was sent to Europe by the War Department on an inspection tour of mines, public works and military fortifications. Hughes subsequently served in the Mexican–American War, acting as chief engineer on the staff of General John E. Wool in 1846 and General William J. Worth in 1847. He was brevetted major of Topographical Engineers on April 18, 1847 for gallant and meritorious conduct during the Battle of Cerro Gordo. Hughes was promoted to lieutenant colonel of a regiment of Maryland and District of Columbia Volunteers on August 4, 1847, and to colonel on October 1, 1847. In December 1847, he was appointed civil and military governor of the Department of Jalapa and Perote in Veracruz. Hughes was later brevetted lieutenant colonel of Topographical Engineers on May 30, 1848 for meritorious conduct while in Mexico. He was honorably mustered out of the volunteer service on July 24, 1848. From 1849 to 1850, he served as chief engineer of the Panama Railroad, resigning from the regular army on August 4, 1851.