The following letter was written by English emigrant Charles Shelling (1827-1887), a former chaplain in the 56th New York Infantry (serving from September 1861 to December 1862) from Newburgh, Orange county, New York. Charles emigrated to the United States in 1841 aboard the ship Wellington. By 1850, when he was only 24, he was already laboring as a Methodist minister in Concord, Erie county, New York. By 1860 he was married to Laura Jane Draper (1822-1869), the daughter of Rev. Gideon and Ella Elizabeth (Cronise) Draper.

In this incredible 1872 letter, Charles informs his brother Esmond of his safe arrival in Sacramento, California, and shares his observations of the journey which was made on the “Pacific Railroad” which was completed just three years earlier in 1869. Charles made the journey to accept an appointment as the pastor of the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Sacramento. He held the position there for two years and then returned East to accept the pastorate at the Main Street Methodist Episcopal Church in Nashua, New Hampshire. After two years there, he then requested to be transferred back to the Southern California Conference in March 1876 and he was pastor of Pasadena’s Methodist Church until he retired. He died in Alhambra, California, in December 1887, where he had settled prior to 1880.

Transcription

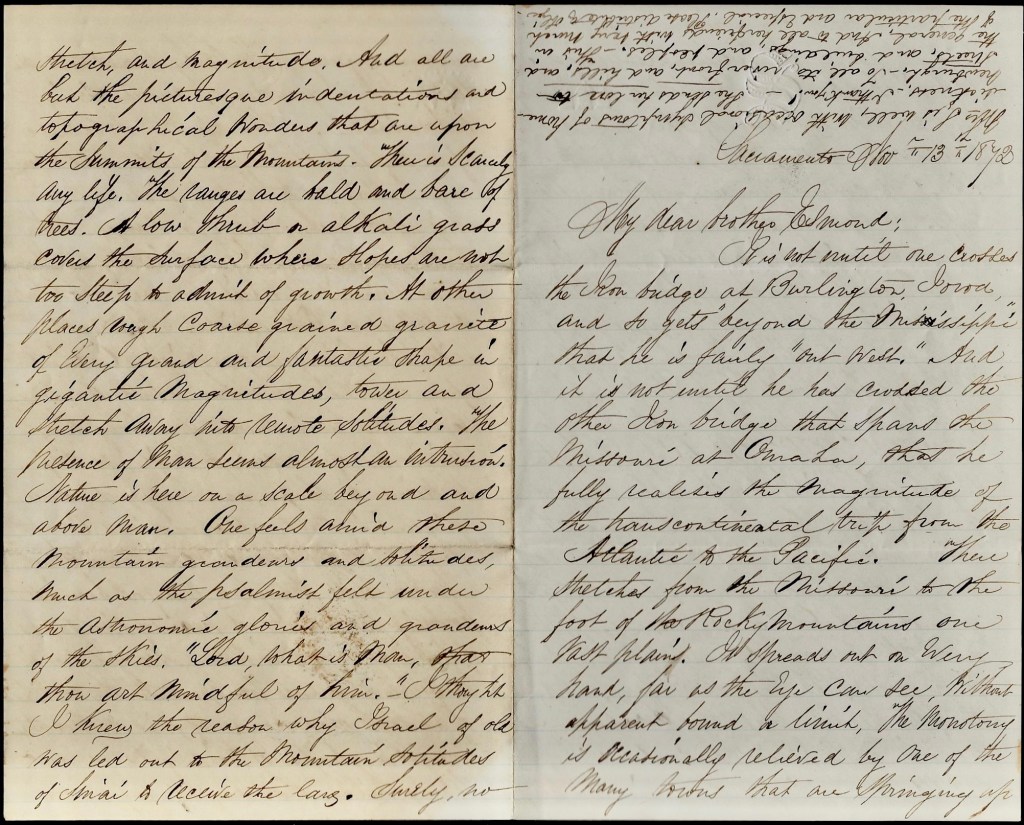

Sacramento, [California]

Nov 13, 1872

My dear brother Esmond,

It is not until one crosses the Iron bridge at Burlington, Iowa, and so gets “beyond the Mississippi” that he is fairly “out West.” And it is not until he has crossed the other Iron bridge that spans the Missouri at Omaha, that he fully realizes the magnitude of the transcontinental trip from the Atlantic to the Pacific. There stretches from the Missouri to the foot of the Rocky Mountains one vast plain. It spreads out on every hand, far as the eye can see, without apparent bound or limit. The monotony is occasionally relieved by one of the many towns that are springing up along the line of the Pacific Railroad.

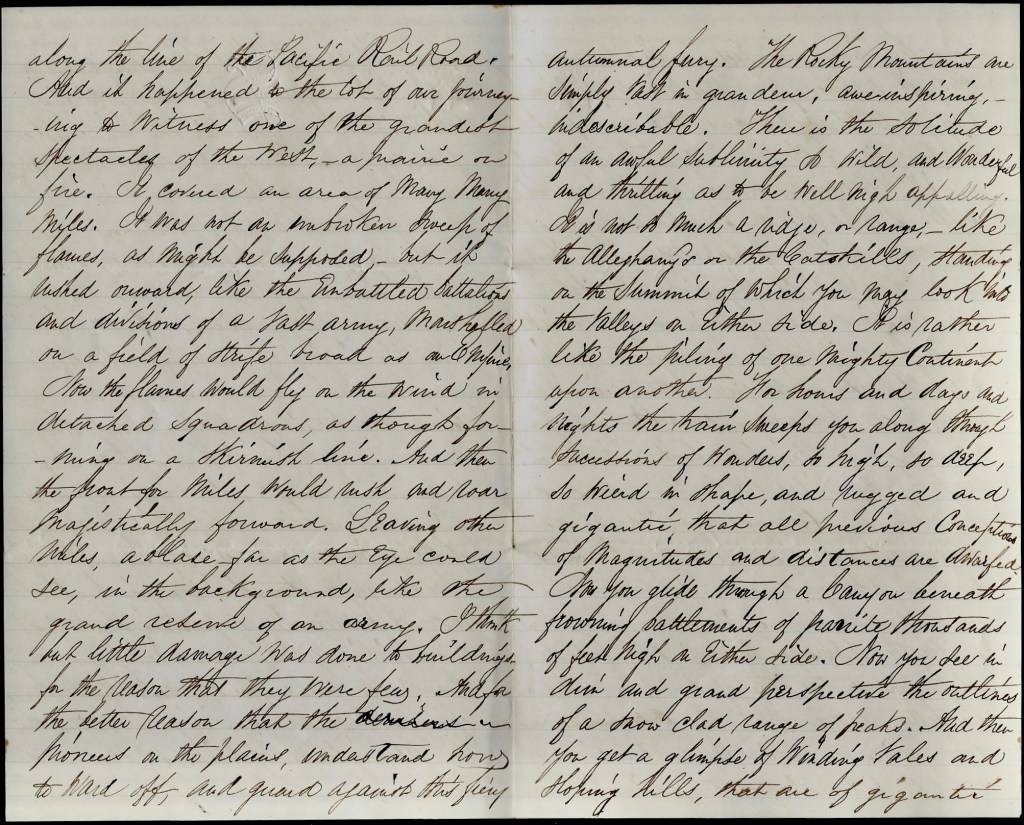

And it happened to the lot of our journeying to witness one of the grandest spectacles of the West—a prairie on fire. It covered an area of many, many miles. It was not an unbroken sweep of flames as might be supposed, but it rushed onward, like the embattled battalions and divisions of a vast army, marshaled on a field of strife broad as an empire. Now the flames would fly on the wind in detached squadrons as though forming on a skirmish line. And then the front for miles would rush and roar majestically forward, leaving other miles ablaze far as the eye could see, in the background, like the grand reserve of an army. I think but little damage was done to buildings for the reason that they were few. And for the better reason that the pioneers on the plains understand how to ward off and guard against this fiery autumnal fury.

The Rocky Mountains are simply vast in grandeur, awe-inspiring, indescribable. There is the solitude of an awful sublimity—as wild, and wonderful, and thrilling as to be well nigh appalling. It is not so much a ridge, or range, like the Alleghany’s or the Catskill’s, standing on the summit of which you may look into the valleys on either side. It is rather like the piling of one mighty continent upon another. For hours and days and nights the train sweeps you along through successions of wonders—so high, so deep, so weird in shape, and rugged and gigantic—that all previous conceptions of magnitudes and distances are dwarfed. Now you glide through a canyon beneath frowning battlements of granite thousands of feet high on either side. Now you see in dim and grand perspective the outlines of a snow-clad range of peaks. And then you get a glimpse of wending vales and sloping hills, that are of gigantic stretch and magnitude. And all are but the picturesque indentations and topographical wonders that are upon the summits of the mountains.

There is scarcely any life. The ranges are bald and bare of trees. A low shrub or alkali grass covers the surface where slopes are not too steep to admit of growth. At other places, rough coarse grained granite of every grand and fantastic shape in gigantic magnitudes, tower and stretch away into remote solitudes. The presence of man seems almost an intrusion. Nature is here on a scale beyond and above man. One feels amid these mountain grandeurs and solitudes much as the psalmist felt under the astronomic glories and grandeurs of the skies. “Lord, what is man, that thou are mindful of him.” I thought I knew the reason why Israel of old was led out to the mountain solitudes of Sinai to receive the laws. Surely, no other place, can be so befitting the throne and footstool of the great and dread Jehovah, as these bare, bald, and solitary sublimities. Here Bossuet’s confession in Notre Dame, is echoed in awe-thrilled whisperings—“God only is great.”

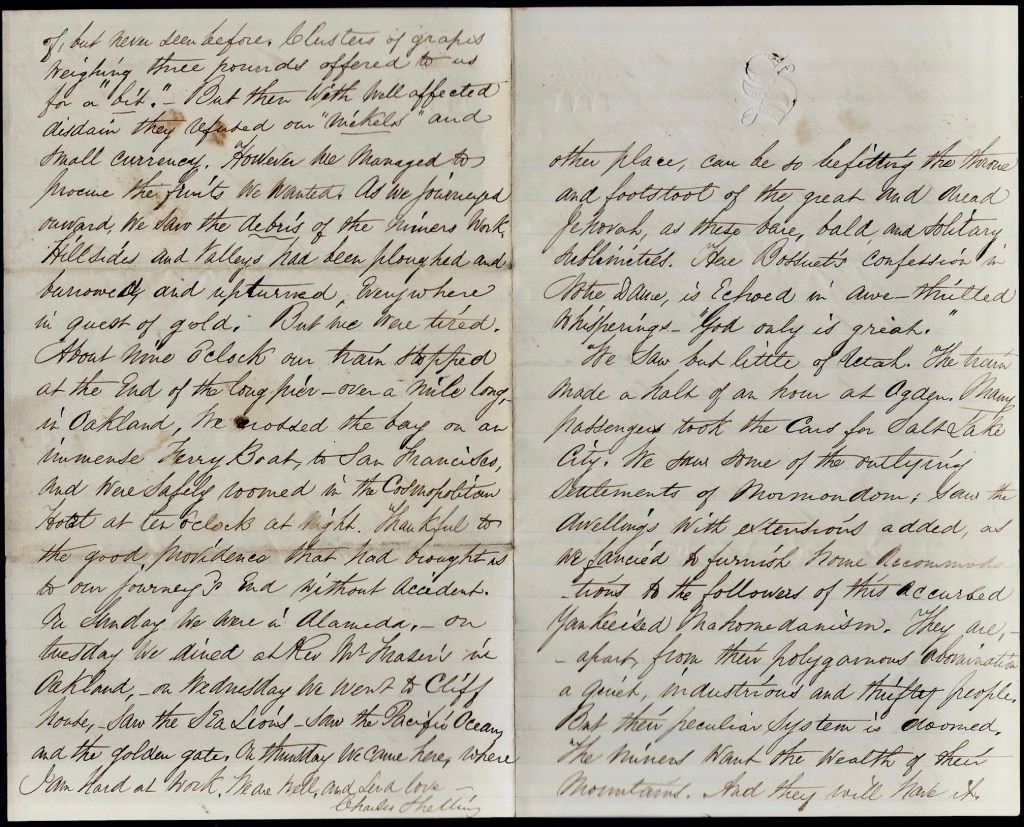

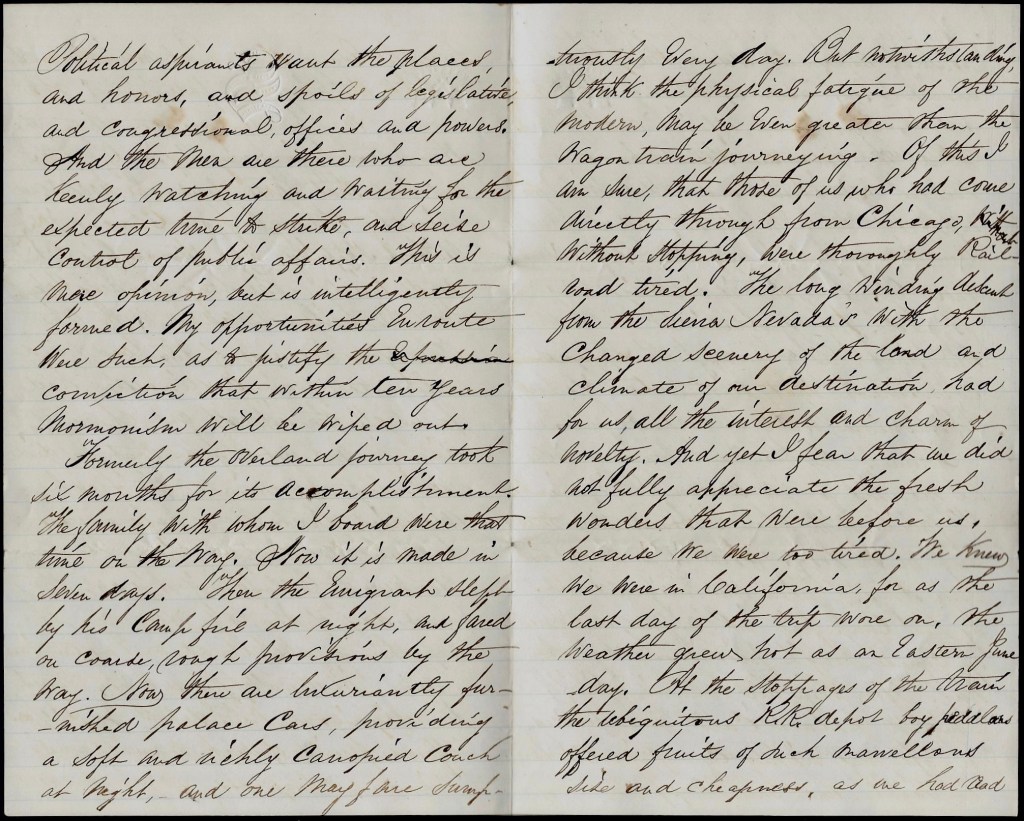

We saw but little of Utah. The train made a halt of an hour [stop] at Ogden. Many passengers took the cars for Salt Lake City. We saw some of the outlying settlements of Mormondom; saw the dwellings with extensions added, as we fancied to furnish home accommodations to the followers of this accursed Yankeeised Mahomedanism. They are—apart form their polygamous abomination—a quiet, industrious, and thrifty people. But their peculiar system is doomed. The miners want the wealth of their mountains. And they will have it. Political aspirants want the places and honors and spoils of legislative and congressional offices and powers. And the men are there who are keenly watching and waiting for the expected time to strike and seize control of public affairs. This is mere opinion, but it is intelligently formed. My opportunities en route were such as to justify the conviction that within ten years Mormonism will be wiped out.

Formerly the overland journey took six months for its accomplishment. The family with whom I board were that time on the way. Now it is made in seven days. Then the emigrant slept by his camp fire at night and fared on coarse, rough provisions by the way. Now there are luxuriantly furnished palace cars, providing a soft and richly canopied couch at night, and one may fare sumptuously every day. But notwithstanding, I think the physical fatigue of the modern may be even greater than the wagon train journeying. Og this I am sure, that those of us who had come directly through from Chicago without stopping were thoroughly railroad tired. The long winding descent from the Sierra Nevada’s with the changed scenery of the land and the climate of our destination had for us all the interest and charm of novelty. And yet I fear that we did not fully appreciate the fresh wonders that were before us because we were too tired. We knew we were in California for as the last day of the trip wore on, the weather grew hot as an Eastern June day.

At the stoppages of the train, the ubiquitous railroad depot boy peddlers offered fruits of such marvelous size and cheapness as we had read of but never seen before. Clusters of grapes weighing three pounds offered to us for a “bit.” But then with well-affected disdain they refused our “nickels” and small currency. However, we managed to procure the fruits we wanted. As we journeyed onward, we saw the debris of the miners’ work. Hillsides and vallies had been ploughed, burrowed, and upturned everywhere in quest of gold.

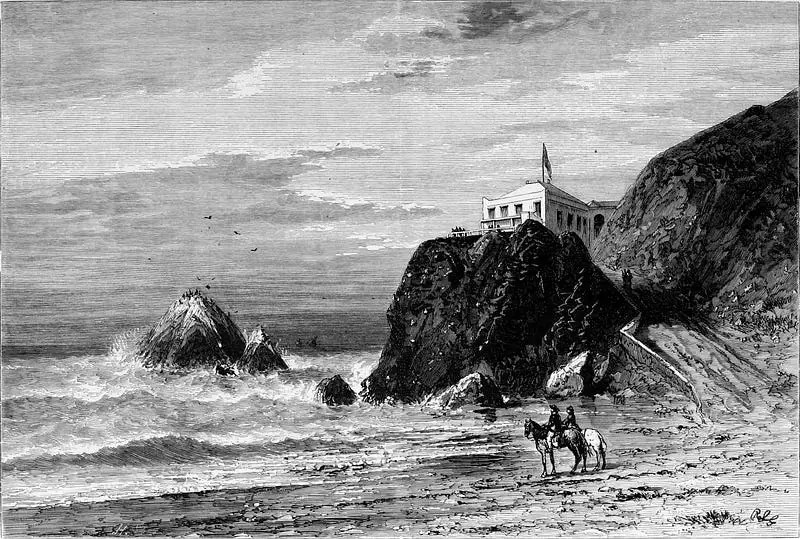

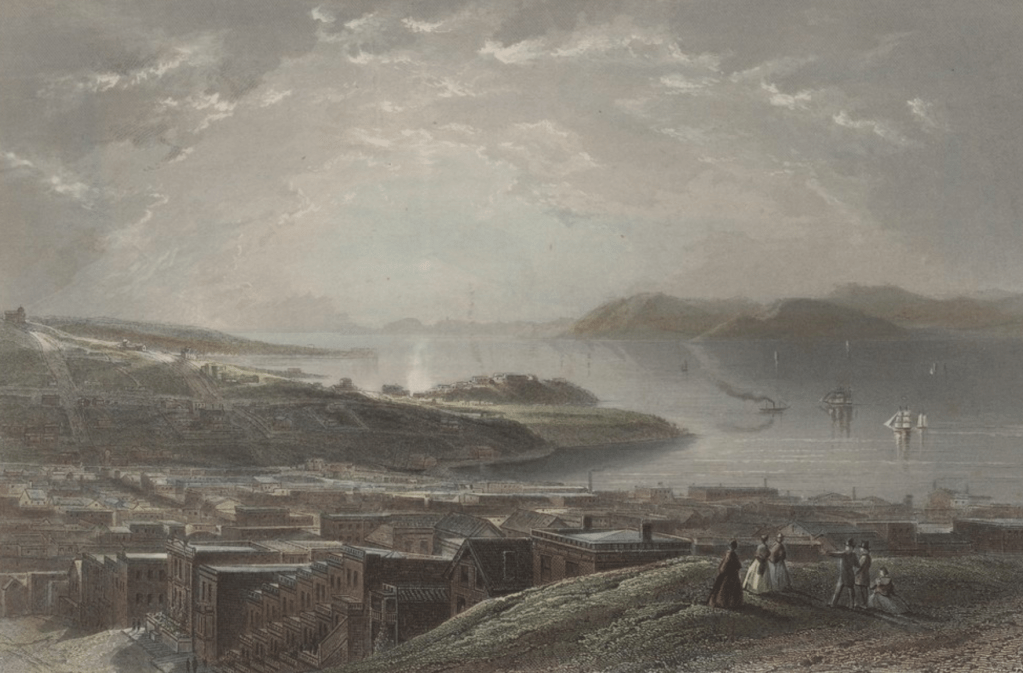

But we were tired. About nine o’clock our train stopped at the end of the long pier—over a mile ling—in Oakland. We crossed the bay on an immense ferry boat to San Francisco and were safely roomed in the Cosmopolitan Hotel at ten o’clock at night, thankful to the good Providence that had brought us to our journey’s end without accident. On Sunday we were in Alameda. On Tuesday we dined at Rev. Mr. Fraser’s in Oakland. On Wednesday we went to Cliff House, 1 saw the sea lions, saw the Pacific Ocean, and the Golden Gate. On Thursday we came here where I am hard at work. We are well and send love, — Charles Shelling

Mrs. S. is well, with occasional symptoms of homesickness. I thank you! She sends her love to Newburgh—to all its river front and hills, and streets and buildings, and peoples. This in the general. And to her friends with very much of the particular and especial. Please distribute and oblige.

1 According to the National Parks Service, the original Cliff House was built as a resort retreat for wealthy hunters and picnickers. It opened in 1863. Perched on a cliff above Land’s End, the Cliff House was originally very remote from downtown San Francisco, which was a small city at the time.