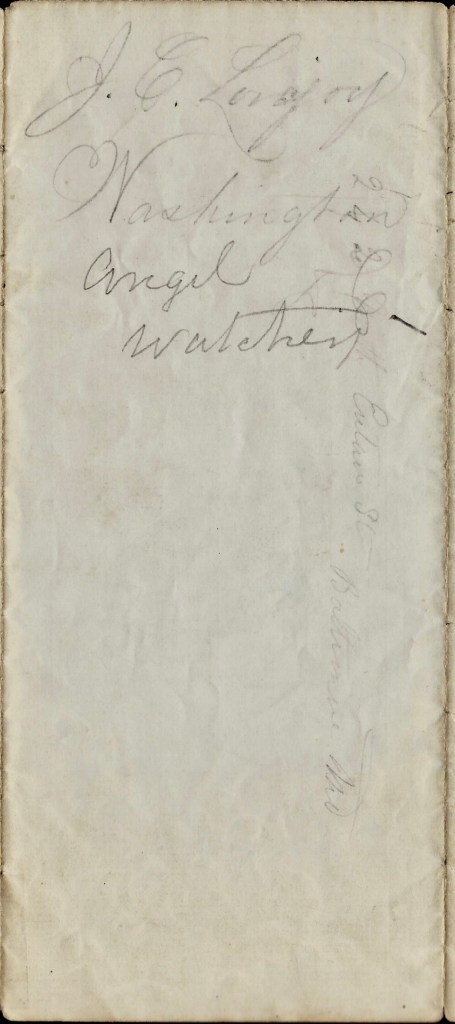

The poem titled “The Angel Watchers” comes from a private collection and is a precious piece of history. It was penned presumably in July of 1863, as indicated at the top of the page. On one of the pages, the name “J. C. Lovejoy” is inscribed, sparking curiosity about the author’s identity. Months after I posted this poem on Spared & Shared, I received a solid clue (see comments) from Eric Pominville who suggested the poem was written by Joseph Cammett Lovejoy (1805-1871), the older brother of Congressman Owen Lovejoy. According to Eric, who has been researching Armory Square General Hospital, he reports that Amanda Akin Stearns (1909) memoir, The Lady Nurse of Ward E, Mr. Lovejoy was a frequent visitor at Armory Square and was well known to the hospital staff. Writing under the date May 14, 1863: “A gallant old gentleman in Congress (brother of Owen Lovejoy, the noted Abolitionist) was introduced to us by Mrs. [Henrietta Crosby] Ingersoll. He says, “We can take care of the soldiers, and he will take care of us,” so he comes quite often to accompany us in a walk after supper through the Capitol grounds. He writes verses, and is a friend of Mrs. Sen. [Henry Smith] Lane. Tomorrow for diversion, he is to take a party of us to another hospital, where they have theatrical entertainments.” Akin, The Lady Nurse of Ward E, (1909), p. 27-28.

I have searched the internet extensively to look for evidence that this poem was published at some time but could not find it. That search included newspapers and “Google Books,” etc. The Armory Hospital was established in 1862. It was constructed on land adjacent to the Smithsonian Institution, approximately where the National Air and Space Museum is today. There was an anniversary celebration at the hospital in August 1863. Perhaps that is when this photograph was taken and was the occasion for the poem.

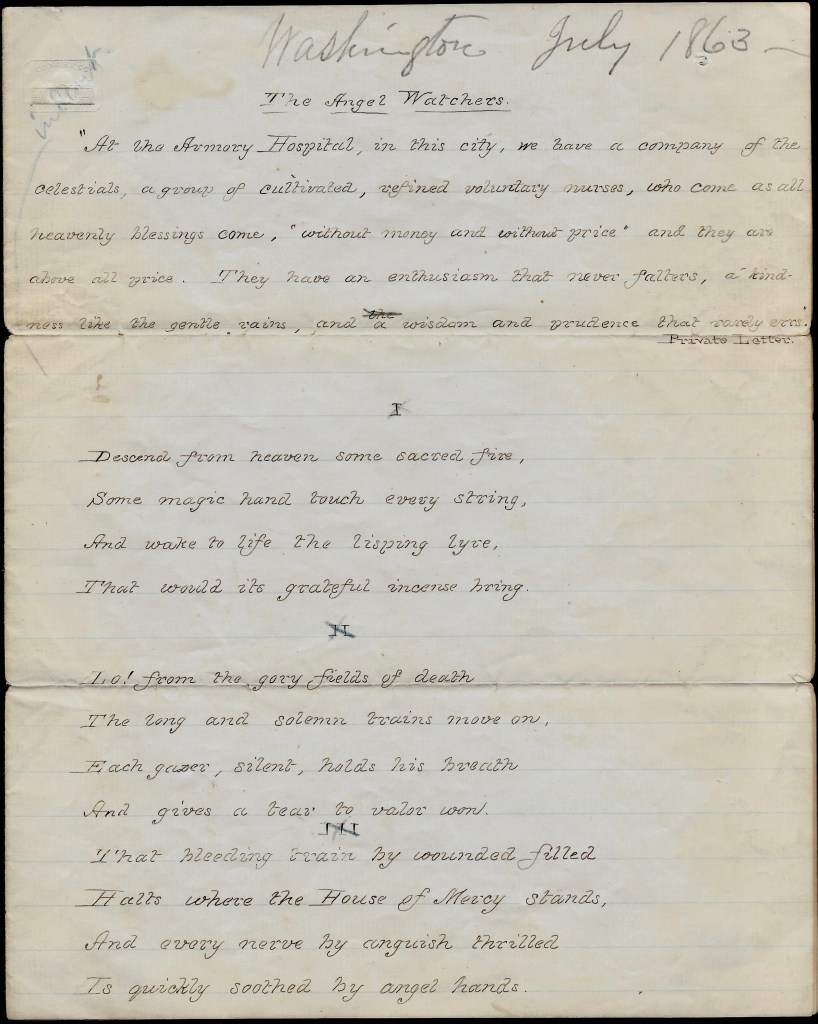

The Angel Watchers

At the Armory Hospital, in this city, we have a company of the celestials, a group of cultivated, refined voluntary nurses, who come as all heavenly blessings come, “without money and without price” and they are above all price. They have an enthusiasm that never falters, a kindness like the gentle rains, and a wisdom and prudence that rarely errs. Private Letter.

Descend from heaven some sacred fire,

some magic hand touch every string,

And wake to life the lisping lyre,

That would its grateful incense bring.

Lo! from the gory fields of death

The long and solemn trains move on,

Each gazer, silent, holds his breath

And gives a tear to valor won.

That bleeding train by wounded filled

Halts where the House of Mercy stands,

And ever nerve by anguish thrilled

Is quickly soothed by angel hands.

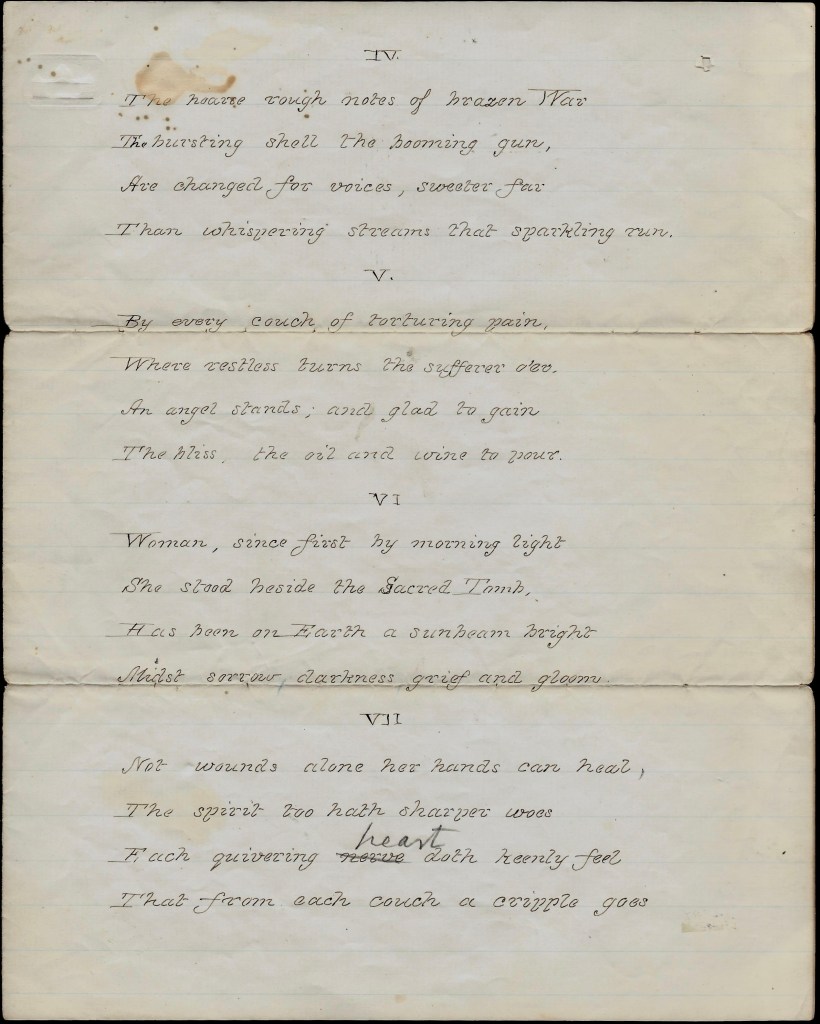

The hoarse rough notes of brazen war

The bursting shell the booming gun,

Are changed for voices, sweeter far

Than whispering streams that sparkling run.

By every couch of torturing pain,

Where restless turns the sufferer o’er,

An angel stands, and glad to gain

The bliss, the oil and wine to pour.

Woman, since first by morning light

She stood beside the Sacred Tomb,

Has born on Earth a sunbeam bright

Midst sorrow, darkness, grief and gloom.

Not wounds alone her hands can heal,

The spirit too hath sharper woes

Each quivering heart doth keenly feel

That from each couch a cripple goes.

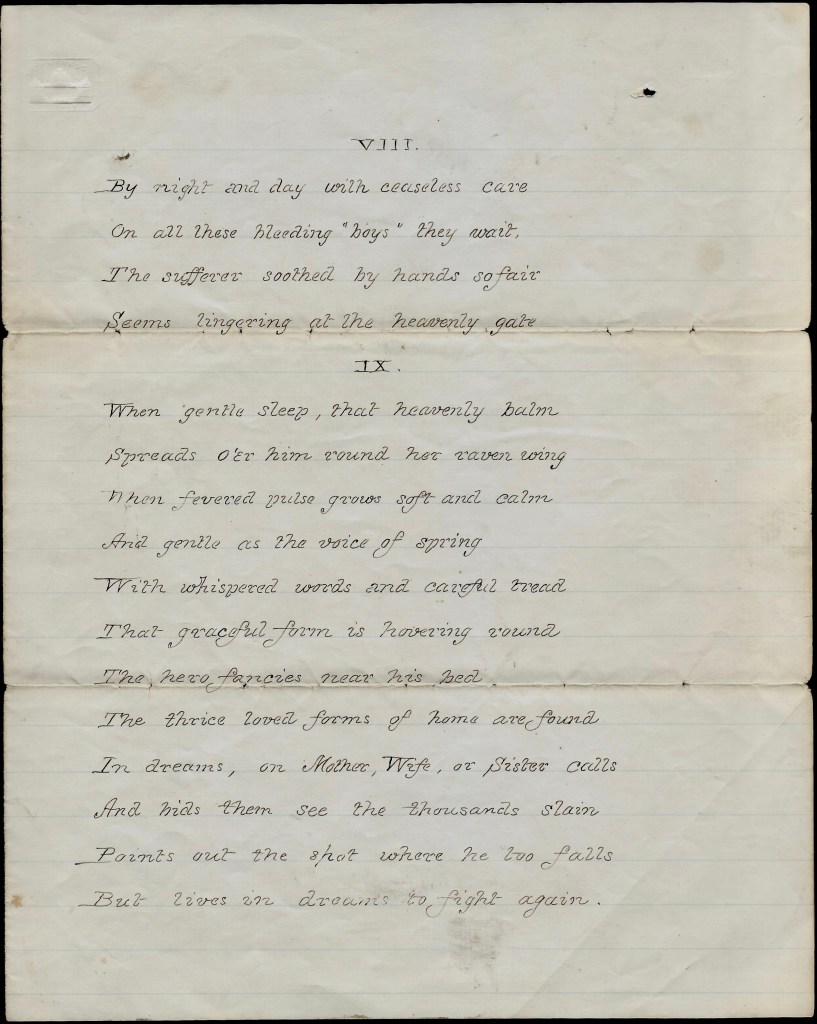

By night and day with ceaseless care

On all these bleeding “boys” they wait,

The sufferer soothed by hands so fair

Seems lingering at the heavenly gate.

When gentle sleep, that heavenly balm

Spreads o’er him round her raven wing

When fevered pulse grows soft and calm

And gentle as the voice of spring

With whispered words and careful tread

That graceful form is hovering round

The hero facies near his bed

The thrice loved forms of home are found

In dreams, on Mother, Wife, and Sister calls

And bids them see the thousands slain

Points out the spot where he too falls.

But lives in dreams to fight again.