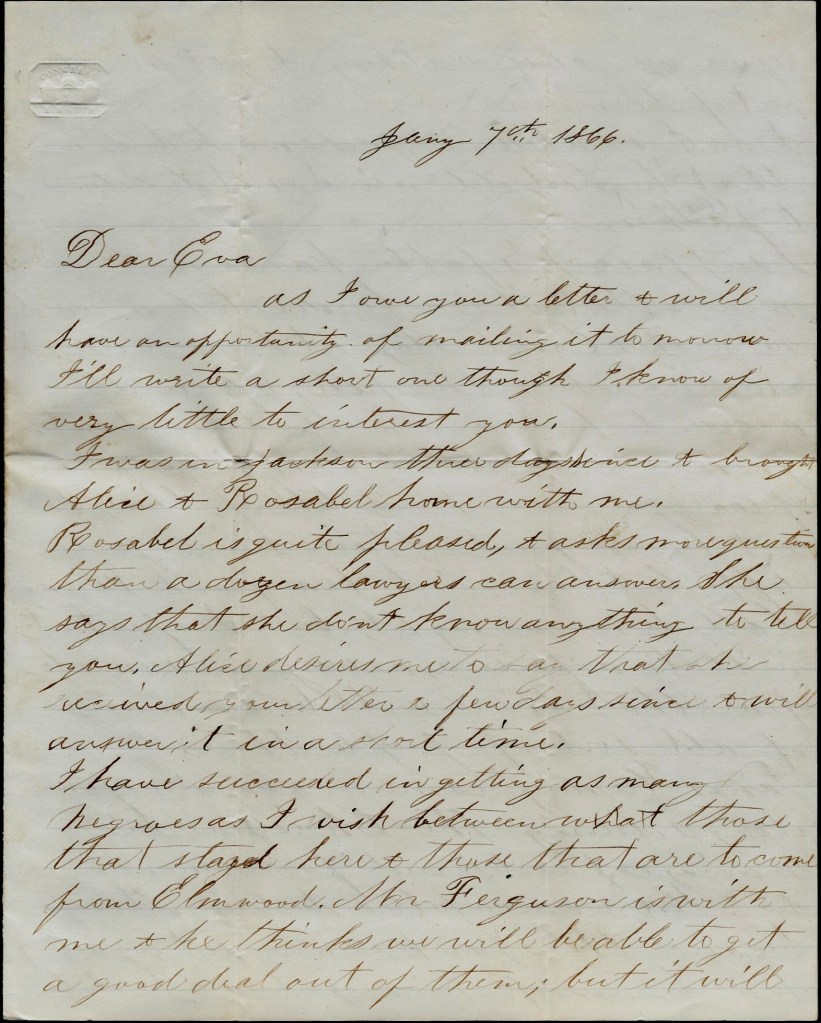

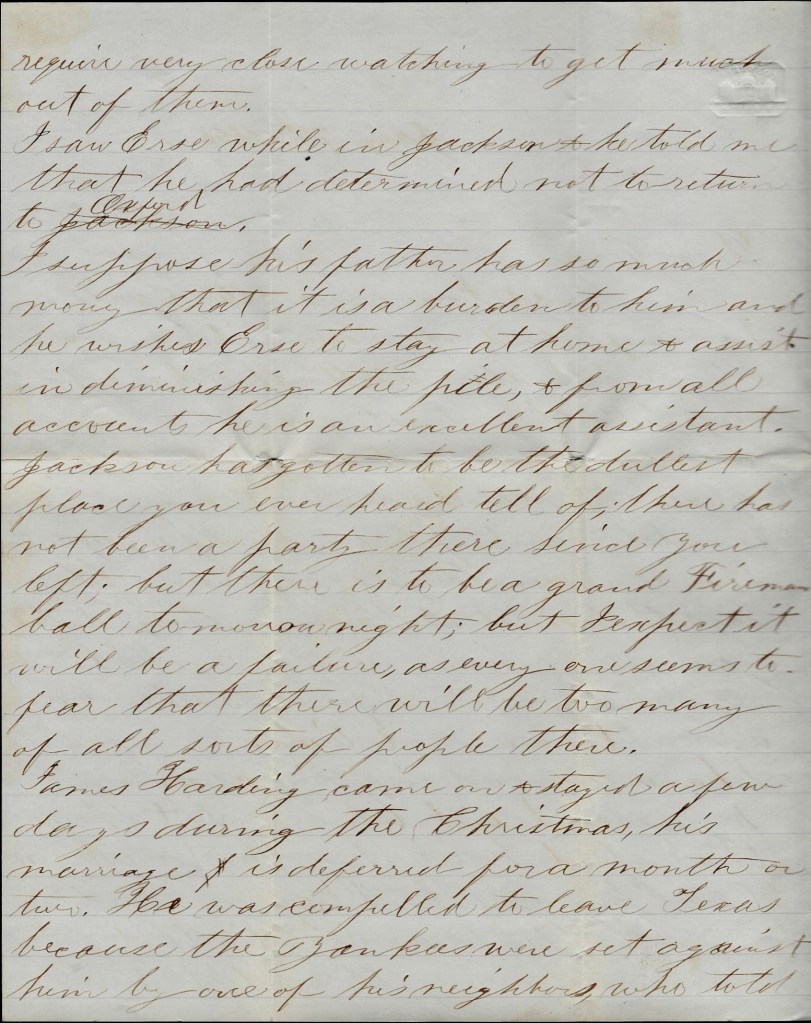

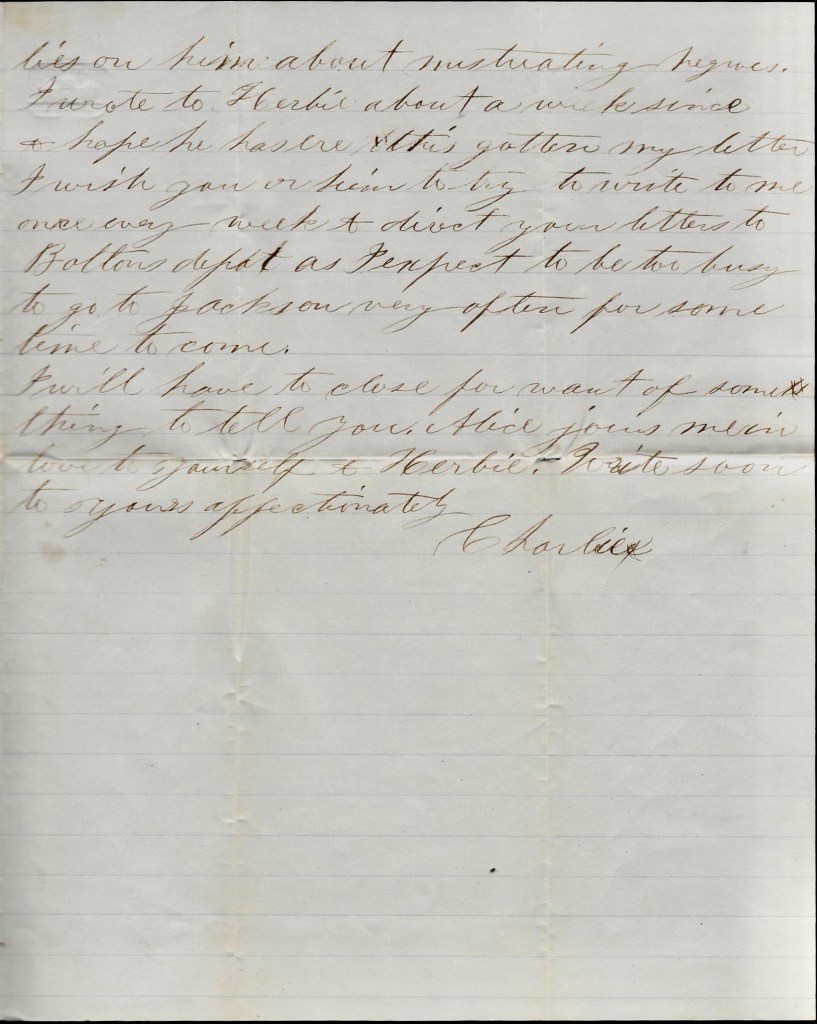

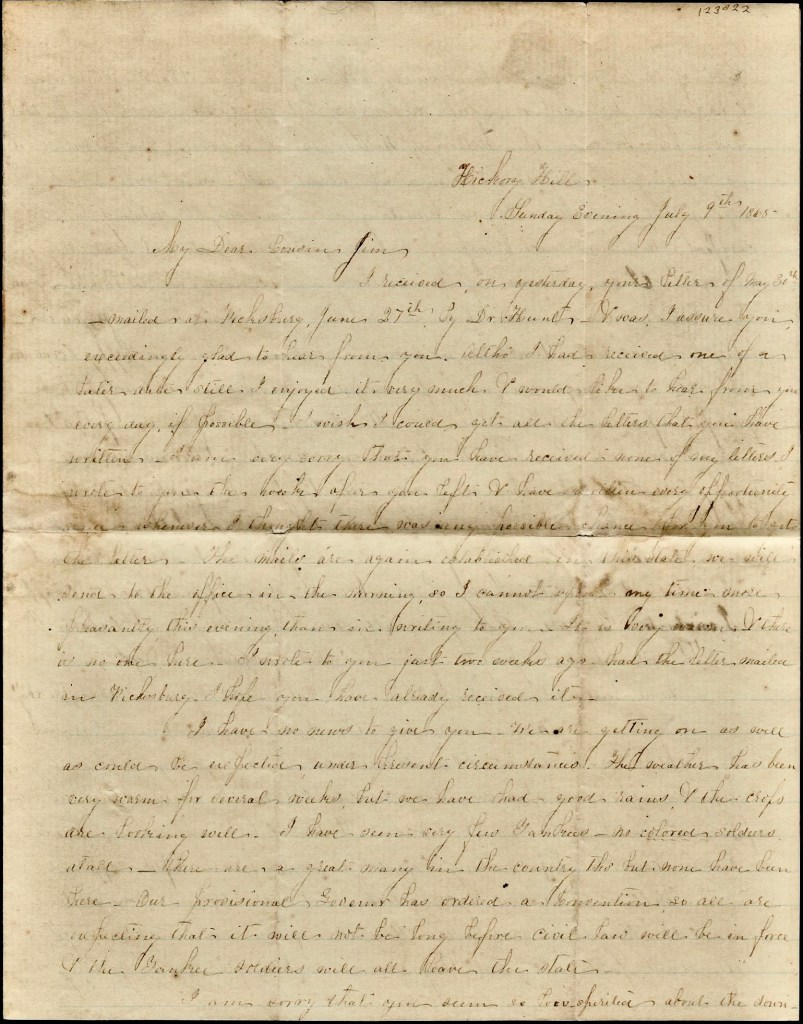

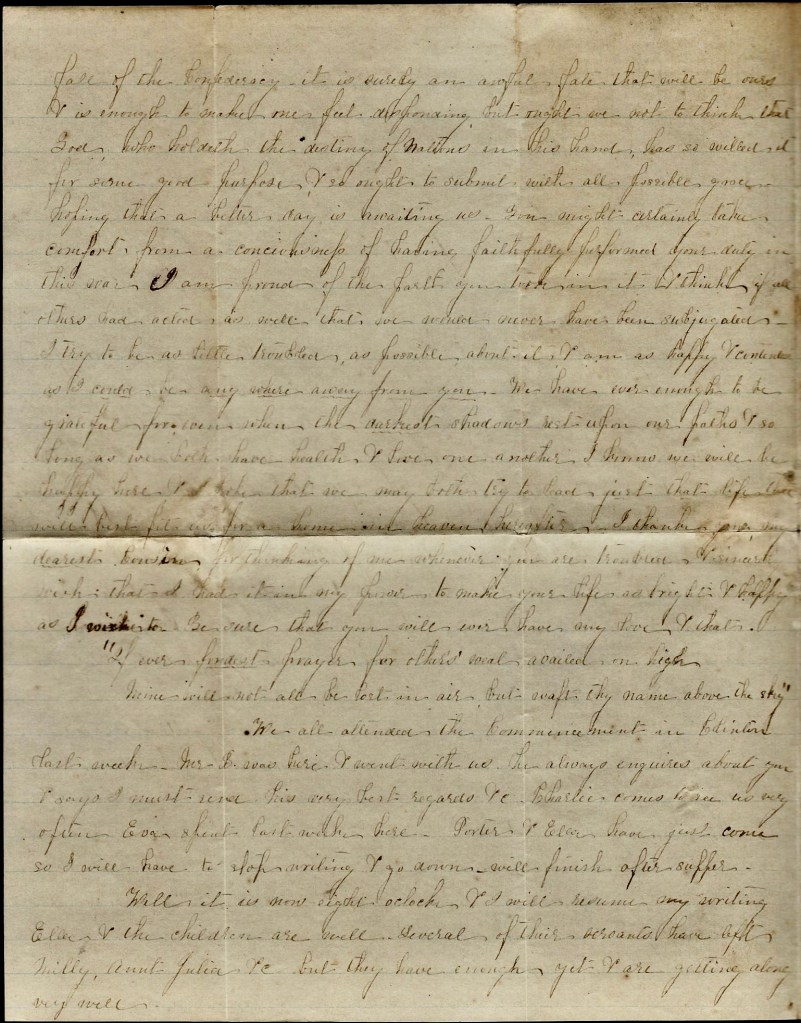

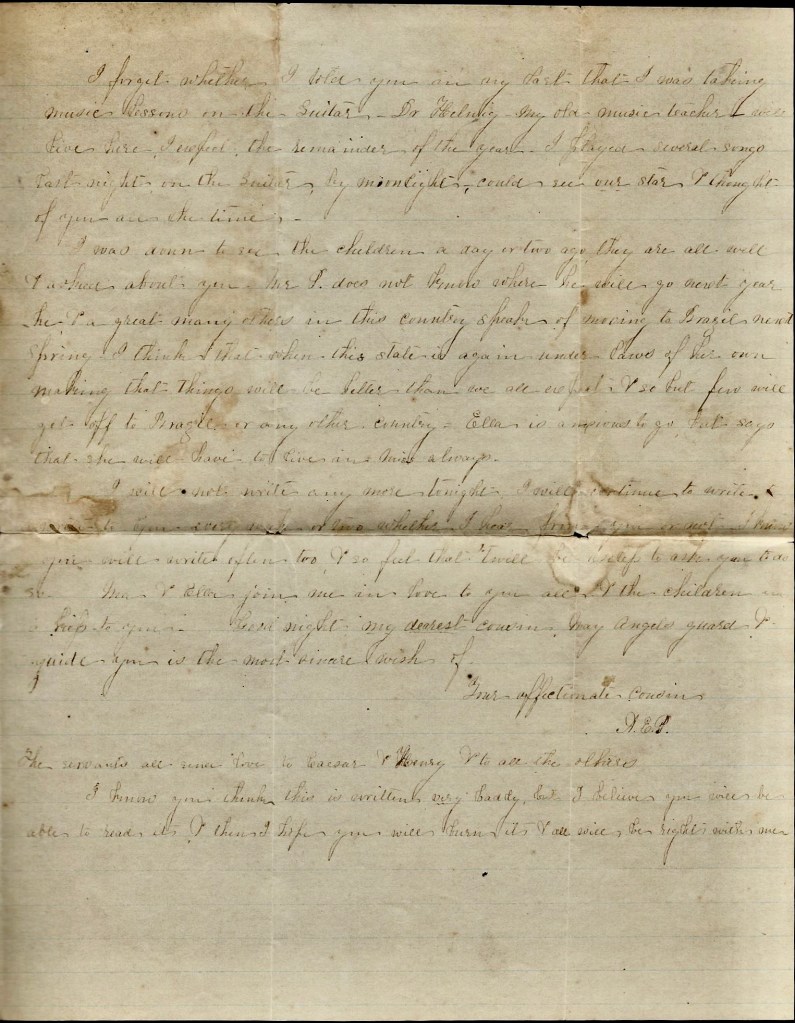

The following letter was written by David Hopkins (1838-1895), the son of William Hopkins (1805-1863) and Emma Hopkins (1808-1868) of Richland county, South Carolina. David wrote the letter from his farm in Canton, Madison county, Mississippi, to his widowed mother in South Carolina. After her husband William Hopkins died in 1863, his wife struggled to get by and to take care of what was left of the plantation. The Federal troops burned much of it but did not burn the main house when they saw a Masonic plaque on the wall. The sons were kept busy trying to run the other family plantations, including those in Mississippi.

David was married in 1859 to Adeline (“Addie”) M. Rembert. David’s obituary reads: David Hopkins was born at the old family homestead near Hopkins, on November 11, 1836. When the war came on he went forth to fight for the beloved Southland in Capt. Meighan’s Company C, Second South Carolina Cavalry, commanded by Col. Thomas J. Lipscomb. He fought throughout the war, distinguishing himself for his bravery. Mr. Hopkins was always a planter. Just after the war he removed to Mississippi, where he remained for fourteen years and then returned to the old homestead, where he has since resided. He married early in life a Miss Rembert of Sumter county, who with his only surviving child, Dr. James Hopkins, the county auditor, remain to mourn the loss. His only other child, a son, died several years ago.

This letter is from a private collection (RM) and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent. See also 1861: James Hopkins to William Hopkins from the same collection.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

April 20, 1868

Dear Mother,

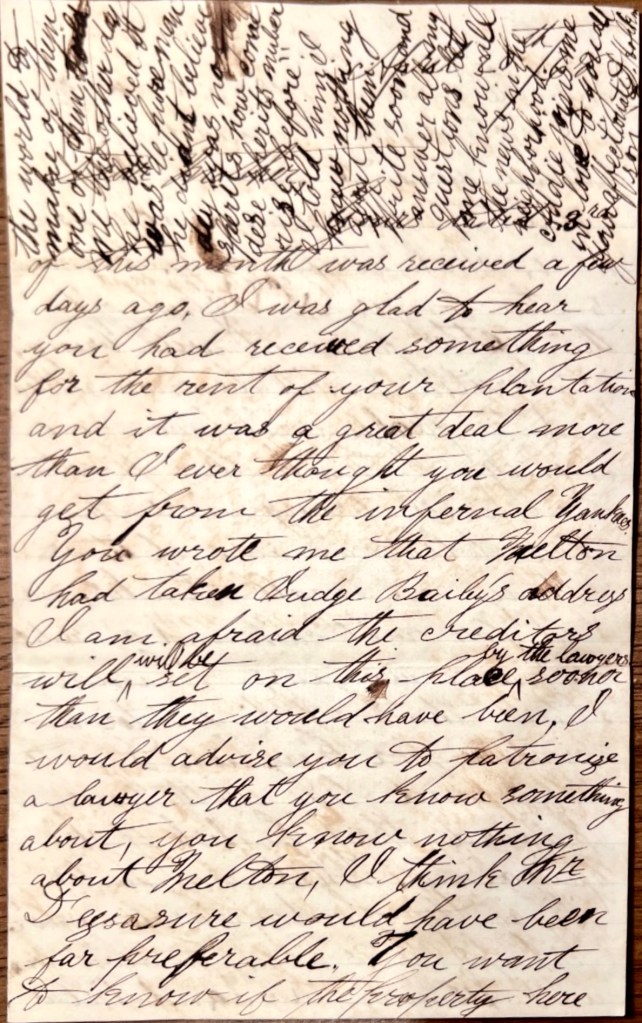

Yours dated 3rd of this month was received a few days ago. I was glad to hear you had received something for the rent of your plantation and it was a great deal more than I ever thought you would get from the infernal Yankees. You wrote me that Melton had taken Judge Bailey’s address. I am afraid the creditors will be set on this place by the lawyers sooner than they would have been. I would advise you to patronize a lawyer that you know something about. You know nothing about Melton. I think Mr. D’ysasure would have been far preferable.

You want to know if the property here has been administered on. It has not, and I would not advise you to have it done until the creditors make you do so which will be time enough as the longer the sale of this land is put off, the better the price will be more settled and the people will have more money. I think the plantation will bring more than three dollars an acre if it is cut up in small tracks and sold for part cash and a credit of one or two years.

I understand that Ned Gunter has written for [brother] English to go to Alabama and live with him. I heard that English [Hopkins] spoke of going. What is Gunter going to South Carolina for? Perhaps he is going to close down with his four thousand dollar bond. I would find out what that bond was for and see if father’s name is to it. Is Dr. Diseker living with you this year?

How many freedmen are you working? and how many brother I___? What negroes have you got? Is Glasgow with you yet? I hope you have got rid of Silvy and her mulatto set. Who cooks for you? What has become of Monday and my friend Josh? I expect Tom Robertson will have him for one of his aide-de-camps mounted on a long-eared Jack[mule]; wisdom personified.

The days of miracle have come again in this country. The Confederate dead are rising from their graves and walking out of the graveyards from two or three to fifty in a band, and this happens all over the country. They are called the Klu Klux Klan and nobody knows who belongs to the Klan. They are over the whole country. One of them rode up to house and asked a negro for a cup of water. He drank it and several more. Finally he called for a bucket full. He dispatched that and several more buckets full. Said he was very thirsty as he had just risen from his grave and had not drank any water since the Battle of Corinth where he was killed. The negro run off as hard as he could, bellowing with all his might to save him.

I heard that a white man was killed about 7 or 8 miles from here two or three days ago. He was a notorious horse thief and had just stolen one. Nobody knows who killed him but it is thought the Klu Klux Klan did it. They have also ordered another man off that I knew. He lives about 6 miles from here. He had a negro wife and had perjured himself in court. He is going to leave as quick as possible. The negroes do not know what in the world to make of them. One of them told me the other day he believed it was “de foreman. He didn’t believe dey was no spirits. How come dese spirits nuber rise before.” I told him I knew nothing about them.

Write soon and answer all my questions. Let me know all the news in the neighborhood. Addie joins me in love to you all. Your affectionate son, — D. Hopkins