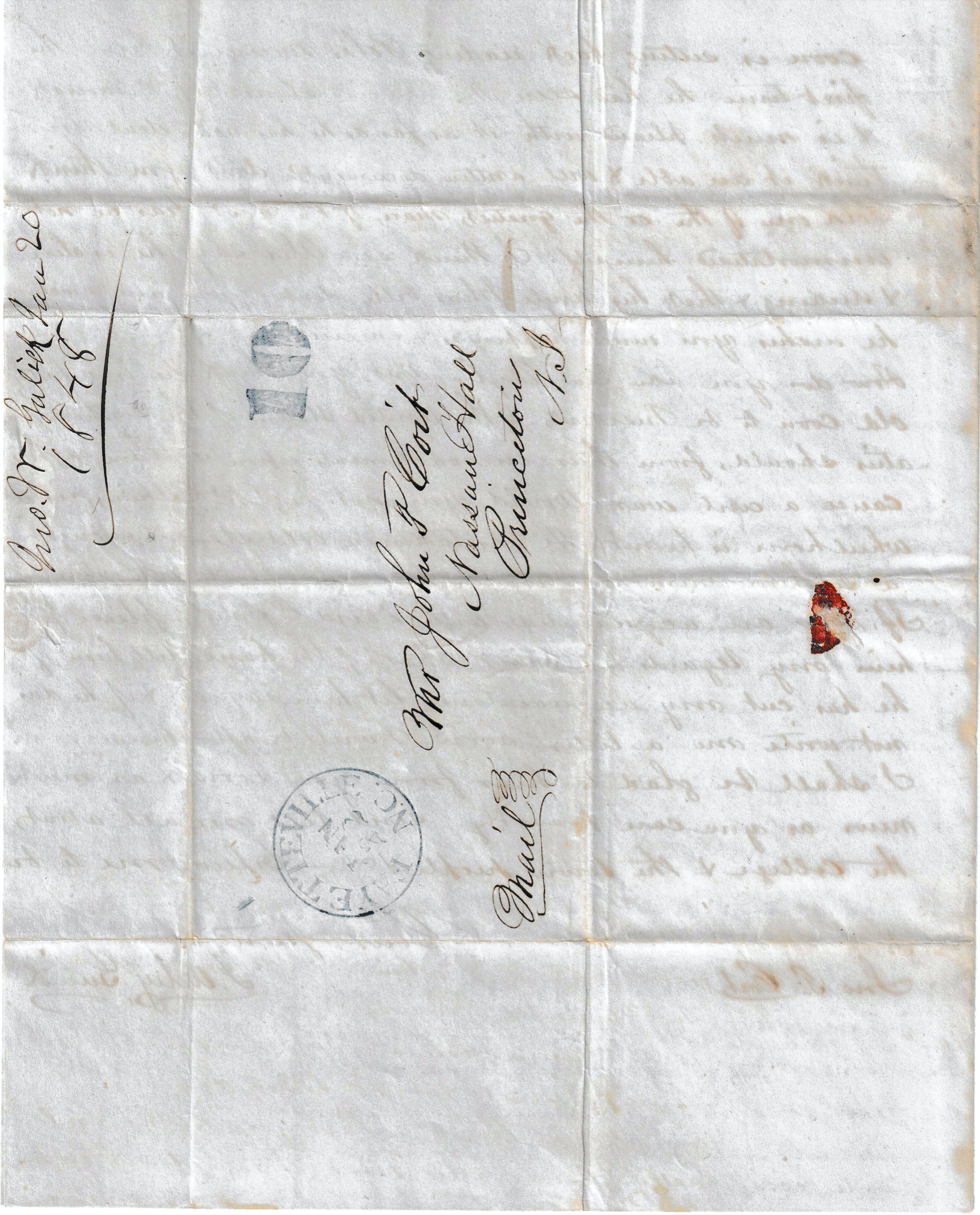

The following 1844 letter was written by James McMullin (1810-Aft1853)—a wood corder and local politician of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He wrote the letter to his sister Rebecca (McMullin) Engelbrecht (1802-1847) and her husband Michael Engelbrecht (1792-1886) in Frederick, Maryland. Rebecca and Michael were married in Philadelphia in August 1838.

This letter was written during the “Native American” Movement of 1844 which culminated in riots in Philadelphia. Those born in American, who referred to themselves as “Nativists” were generally opposed to foreign emigration, particular the Irish Catholics.

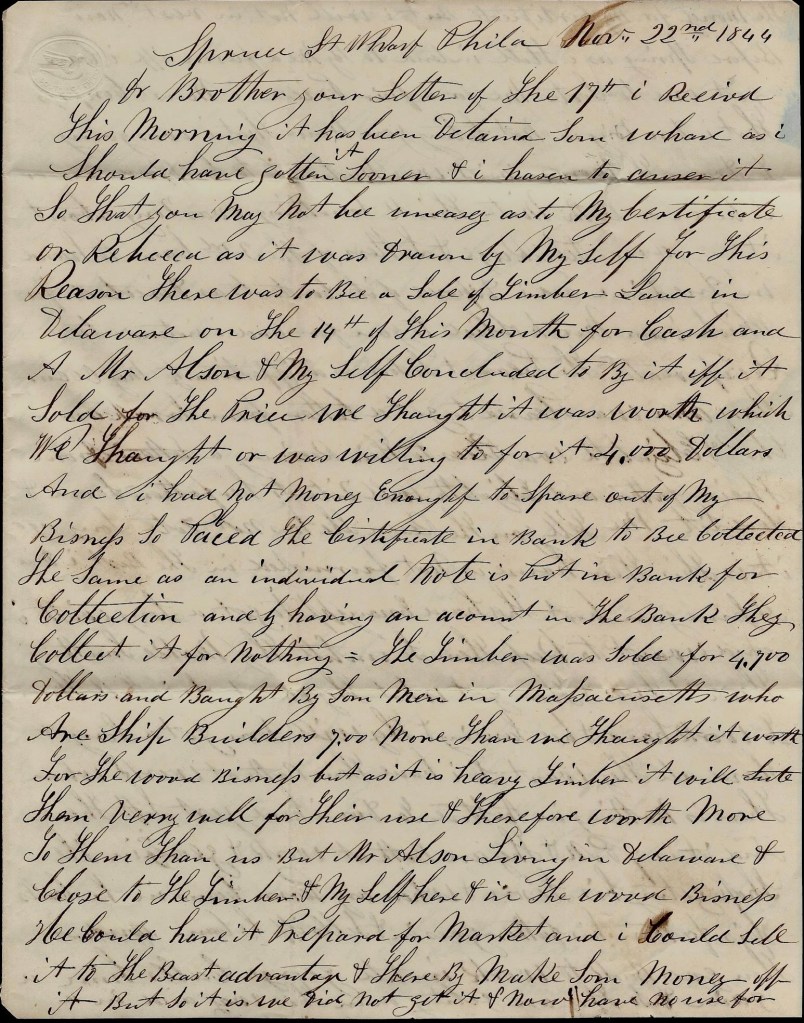

Transcription

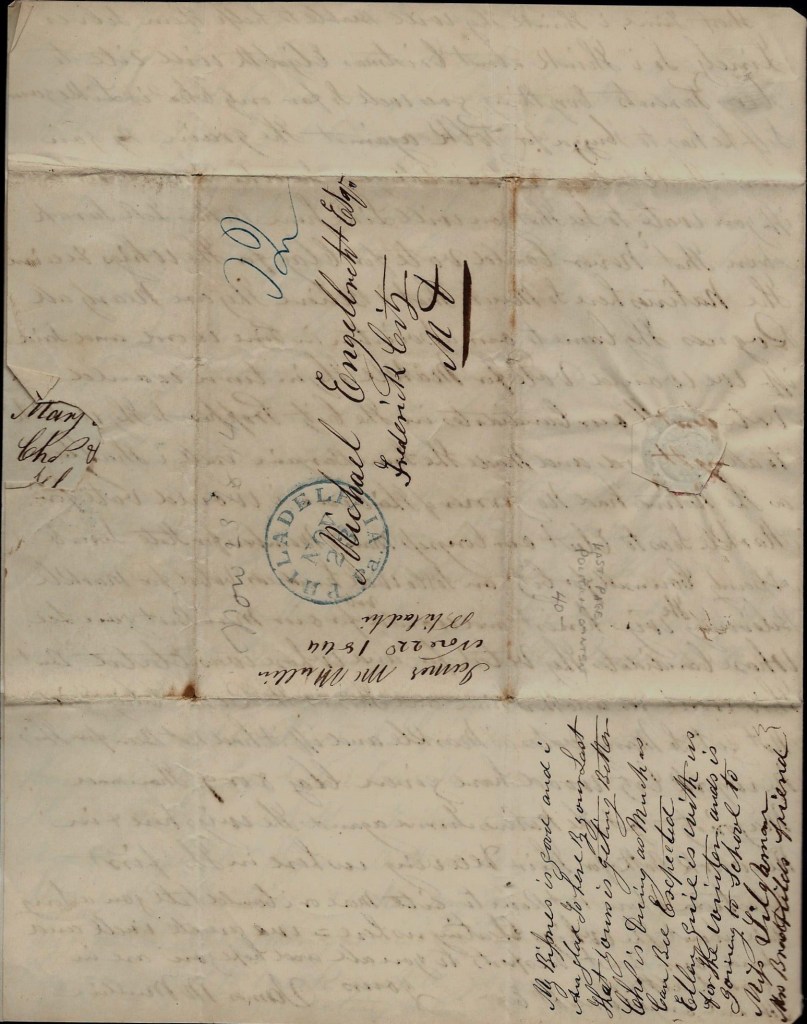

Postmarked Philadelphia, PA

Spruce Street Wharf

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

November 22nd 1844

Dear Brother,

Your letter of the 17th I received this morning. It has been detained somewhere as I should have gotten it sooner & I have to answer it so that you may not be uneasy as to my Certificate or Rebecca as it was drawn by myself for this reason. There was to be a sale of timber land in Delaware on the 14th of this month for cash and a Mr. Alson & myself concluded to buy it if it sold for the price we thought it was worth which we thought, or was willing to [pay] for it 4000 dollars. And I had not money enough to spare out of my business so asked for the Certificate in Bank to be collected, the same that an individual Note is put in bank for collection, and I having an account in the bank, they collect it for nothing. The timber was sold for $4,700 dollars and bought by some men in Massachusetts who are ship builders—700 more than we thought it worth for the wood business, but as it is heavy timber, it will suit them very well for their use & therefore worth more to them than us.

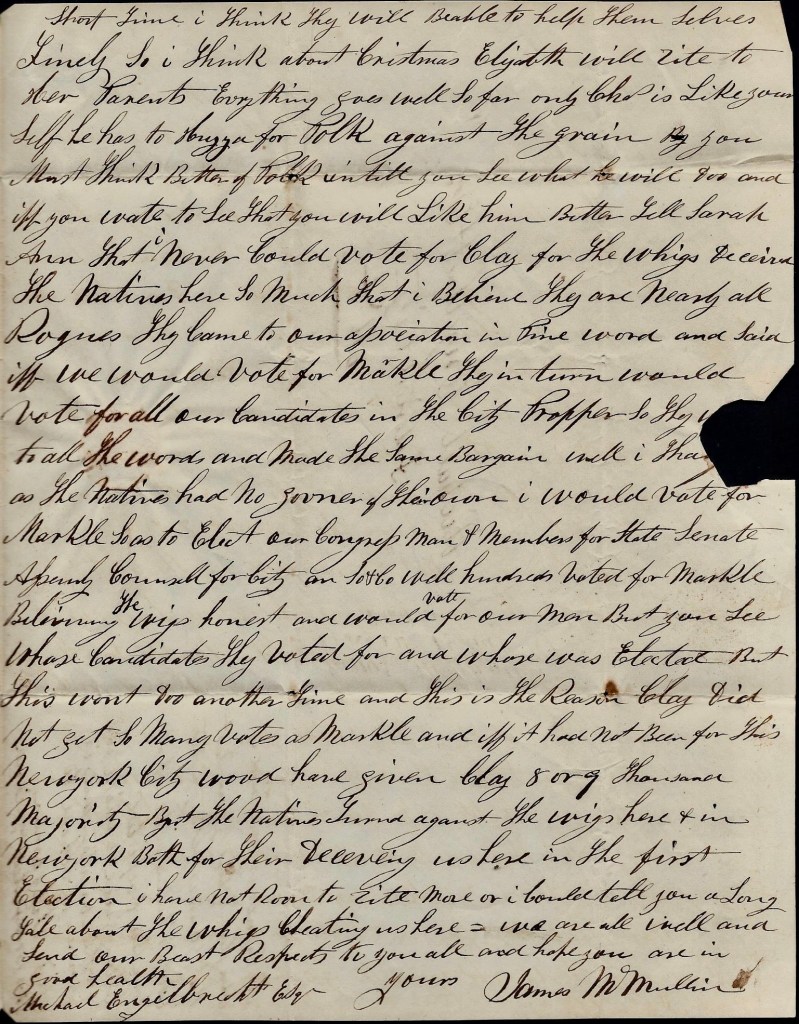

But Mr. Alson, living in Delaware and close to the timber & myself here & in the wood business, he could have it prepared for market and I could sell it to the best advantage & thereby make some money off it. But so it is, we did not get it and now I have no use for the money for my Certificate, but I will not invest it now before spring as I still intend to buy me a farm if I can get one to suit me for a fair price. I must confess that I done wrong in not telling you that I was going to draw the money as it was natural to suppose you or Rebecca or both might think something was wrong about it. Your package and letter of the 3rd came to hand in due time and I disposed of its contents as directed for which I am much obliged to you for I intend to reciprocate the present so soon as an opportunity may occur. Mary Ann was pleased to get a letter from Sarah Ann. Charles & Elizabeth was pleased to their receiving a letter from their father and Elizabeth will write to her father soon. And here let me tell you the reason she has not wrote long ago. It is this. Their house is not furnished in the best, I do assure you, but they have enough to get along with and I want to keep them so until they make something themselves & then get what they want. So I tell them to work hard and be saving & they will soon get along & have all they want. So I have them both at work when there is nothing in the store to do. I have just left there and it is 7 p.m. and they are both at work & George is in the shop getting his lesson & when any person comes in, he calls his father, goes in and sells if he can. Then goes back to work until George calls him again & so they are getting along in this way and in a short time I think they will be able to help themselves finely. So I think about Christmas Elizabeth will write to her parents.

Everything goes well so far—only Charles is like yourself, he has to Huzza for Polk against the grain. You must think better of Polk until you see what he will do and if you wait to see that, you will like him better. Tell Sarah Ann that I never could vote for Clay for the Whigs deceived the Natives here so much that I believe they are nearly all rogues. They came to our association in Pine Wood and said if we would vote for Markle, they in turn would vote for all our candidates in the city proper. So they went to all the wards and made the same bargain. Well, I thought as the Natives had no Governor of their own, I would vote for Markle so as to elect our Congressman & members for State Senate Assembly Council for City and &c. Well hundreds voted for Markle believing the Whigs honest and would vote for our man but you see whose candidates they voted for and whose was elected. But this won’t do another time and this is the reason Clay did not get so many votes as Markle and if I had not been for this New York City, would have given Clay 8 or 9 thousand majority. But the Natives turned against the Whigs here and in New York both for their deceiving us here in the first election.

I have not room to write more or I could tell you a long tale about the Whigs cheating us here. We are all well and send our best respects to you all and hope you are in good health. Yours, — James McMullin

To Michael Englebrecht, Esq.