Following is a letter by 61 year-old Archibald Whyte (1800-1865) who was born in Argyle, New York, to Rev. Archibald Whyte, Sr. and Margaret Kerr Whyte. He graduated from Union College and studied at the Associate Presbyterian Seminary in Philadelphia, being licensed to preach by Cambridge Presbytery in 1826. After preaching in North and South Carolina in 1827, he chose to work with a new church in Baltimore from 1827 to 1833. He married Susan Grier from Steele Creek Associate Church around 1829, likely during his mission work.

In 1833, Whyte became the minister at Steele Creek and Back Creek Associate churches in Mecklenburg County and remained there for the rest of his life. He had a daughter named Margaret, born in 1833, but his wife, Susan Grier Whyte, died on December 8, 1834, leaving him to raise their infant daughter alone. During his ministry, his churches grew, but tensions over slavery arose in the late 1830s, as the cotton economy expanded and many began to see slavery as crucial. Those who disagreed often moved to free states. The Associate Presbyterians in the Carolinas faced difficulties since most of their members were in the North, where rules included freeing their slaves. In 1840, Rev. Whyte was suspended from the ministry, and many Associate churches in the Carolinas eventually faded away or joined the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church.

It is intriguing to consider why Archibald Whyte, a New Yorker, became a strong supporter of slavery, dedicating his life to defending the landed gentry. After fourteen years as a minister, at 40, he opted for a career change, not seeking a new position in another denomination like most Southern ministers. Instead, he moved to York County, bought a farm near the Catawba River, and became a successful community member. After his first wife died around 1838 or 1839, he married Mrs. Elizabeth Hart Campbell, likely influenced by her ties to the Campbell family.

Rev. Whyte’s farm covered 317 acres along Saluda Road, between the river and Steele’s Crossing. Today, this area includes parts of I-77, the Manchester Village shopping area, and the Manchester Meadows Soccer Complex. His home was near the southern edge of his property, where Dave Lyle Boulevard meets Springsteen Road. When Rev. Whyte arrived in eastern York County, SC, the region was called “Indian Land,” part of the Catawba Indian Nation’s territory, mostly leased to white settlers.

Archibald Whyte began a new life as a planter in a two-story Piedmont I-house with a front porch and chimneys at both ends, though it’s unclear if he built or bought it; local histories suggest construction was between the 1830s and 1840s. In addition to being a planter and Postmaster, Rev. Whyte preached and ran an inn at his home, teaching young men who came for lessons. By 1850, 50-year-old Whyte from New York lived with his daughter Margaret (17) and sons Thomas (10) and William (8). The Slave Census indicated he owned 12 slaves and his real estate was valued at $3,000, equivalent to about $82,000 today. He owned 200 acres of improved land and 114 acres unimproved, along with two horses, two mules, four milk cows, fourteen oxen, and other livestock, growing wheat, corn, and oats.

In 1856, Whyte began his political career, being nominated and winning a seat in the South Carolina Legislature to represent Indian Land. He served as one of four representatives from York District during sessions in late 1856 and late 1857. That year, he participated in planning the relocation of settlers to Kansas to support slavery and helped establish a voting precinct in Rock Hill, known for his skillful speaking.

The 1860 Census showed that Rev. Archibald Whyte was doing well as a planter, with real estate valued at $9,850 (about $248,000 today) and personal property worth $9,605. He owned eleven slaves, six of whom were over 18, and his address was “Coats Tavern,” located between Lesslie and Catawba, south of his home.

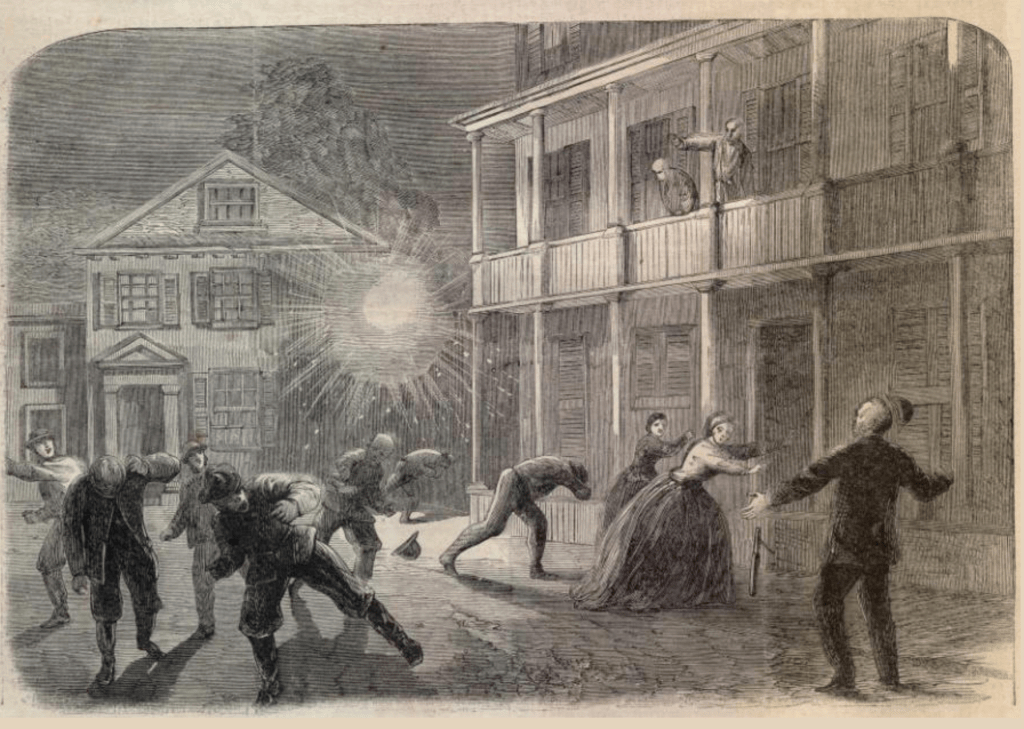

With the coming of the Civil War, Whyte supported the southern cause. In early 1861, A. E. Hutchison organized the first military unit in Rock Hill, named the Whyte Guards in honor of Archibald Whyte. They assembled on April 15, shortly after the firing on Fort Sumter, and Whyte accompanied them to Columbia. In August 1861, he was appointed as an agent for Rock Hill to solicit donations for the Confederate cause. [Source: Rev. Archibald Whyte, by Paul Gettys]

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

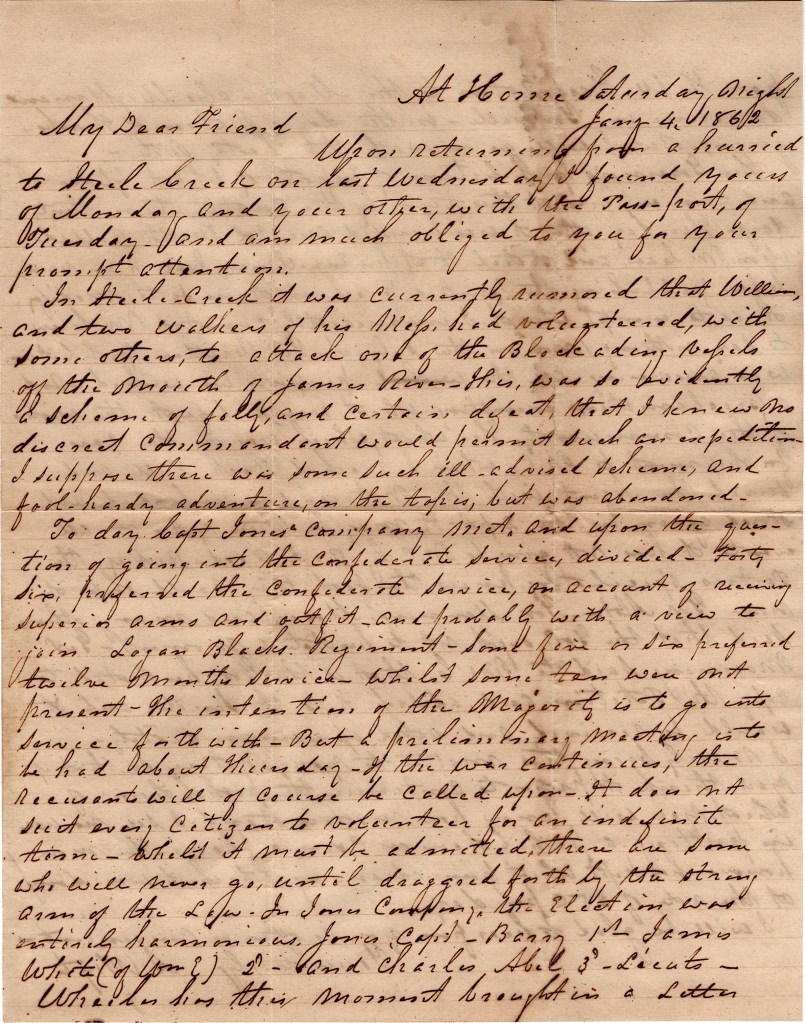

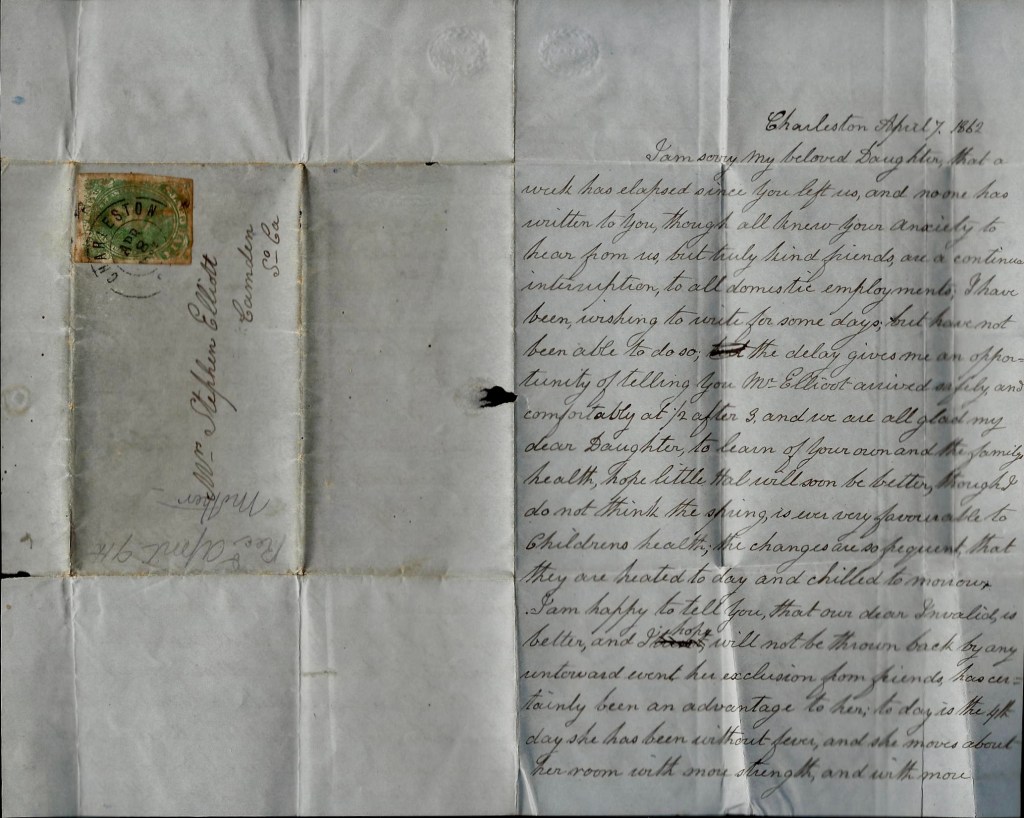

At home [York county, South Carolina]

Saturday night, January 4, 1862

My dear Friend,

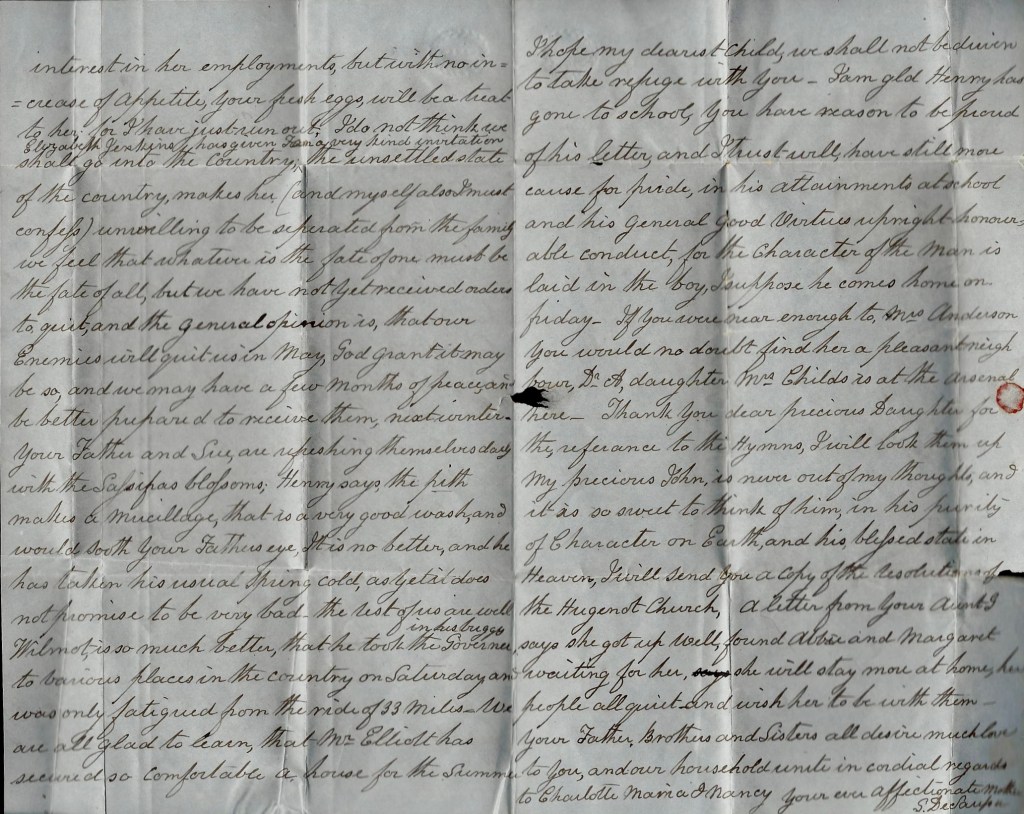

Upon returning from a hurried [trip] to Steele Creek on last Wednesday, I found yours of Monday and your other, with the passport, of Tuesday, and am much obliged to you for your prompt attention.

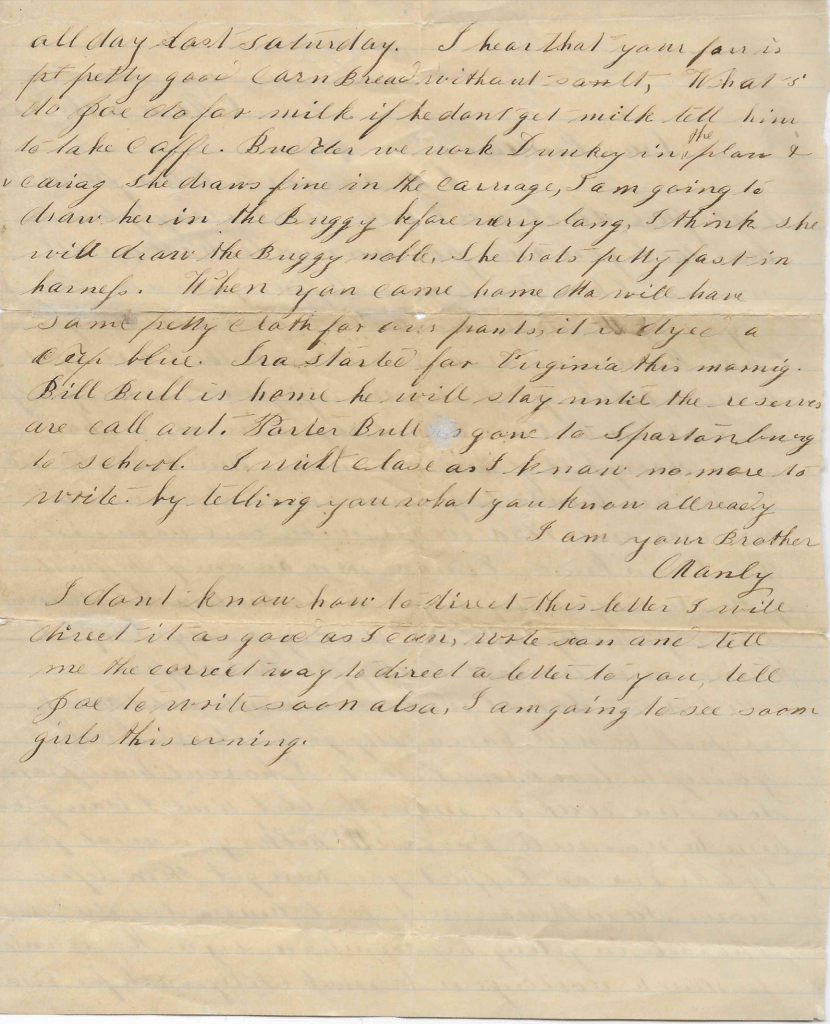

In Steele Creek, it was currently rumored that William and two Walkers of his mess had volunteered with some others to attack one of the blockading vessels off the mouth of James river. This was so evidently a scheme of folly and certain defeat that I knew no discreet commandant would permit such an expedition. I suppose there was some such ill-advised scheme, and fool-hardy adventure on the [ ]; but was abandoned.

Today Capt. Jones’s company met and upon the question of going into the Confederate service, divided. Forty-six preferred the Confederate service of account of receiving superior arms and outfit—and probably with a view to join Logan Black’s Regiment [1st S. C. Cavalry]. Some five or six preferred twelve months service whilst some ten were not present. The intention of the majority is to go into service forthwith, but a preliminary meeting is to be had about Thursday. If the war continues, the [ ] will of course be called upon. It does not suit every citizen to volunteer for an indefinite time. Whilst it must be admitted there are some who will never go until dragged forth by the strong arm of the law. In Jones’ company, 1 the election was entirely harmonious. [Robin C.] Jones, captain. [James H.] Barry, 1st. James White (of Wm E) 2nd. and Charles Abel, 3rd Lieutenants.

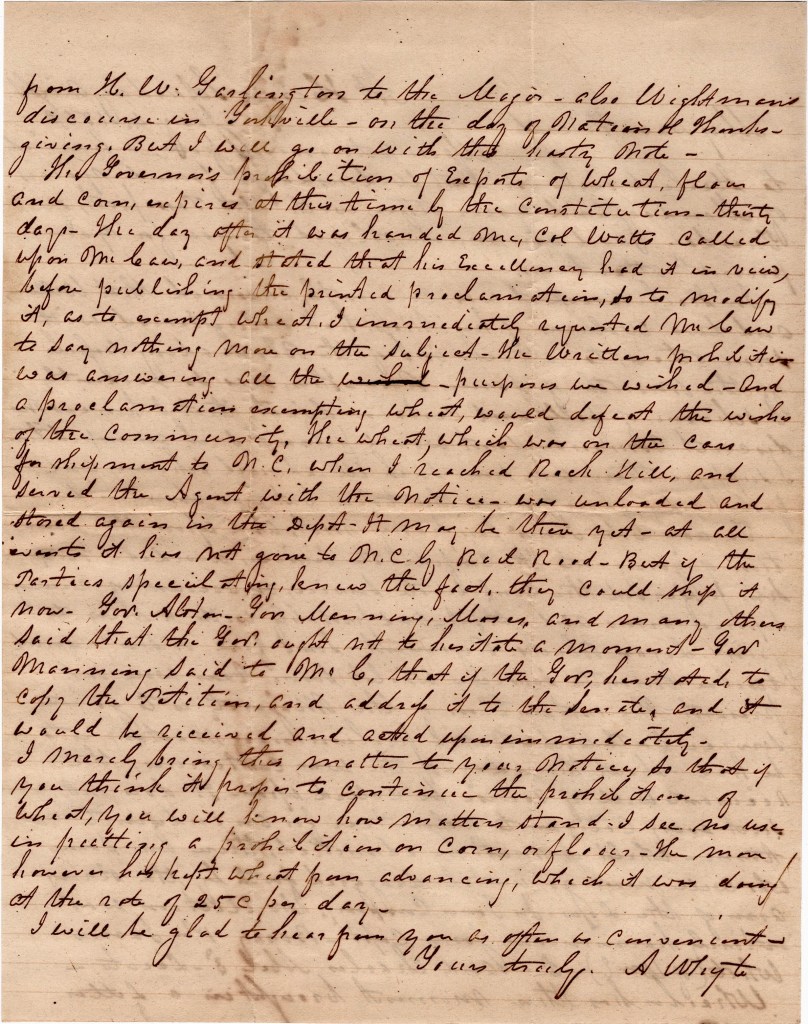

Wheeler has this moment brought in a letter from N. W. Garlington to the Major. Also [John T.] Wightman’s discourse in Yorkville [S. Carolina] on the day of National Thanksgiving. But I will go on with this hasty note.

The Governor’s prohibition of exports of wheat, flour and corn expires at this time by the Constitution—thirty days. The day after it was handed me, Col. Watts called upon McCaw and stated that his excellency had it in view, before publishing the printed proclamation so to modify it, as to exempt wheat. I immediately requested McCaw to say nothing more on the subject. The written prohibition was answering all the purposes we wished, and a proclamation exempting wheat would defeat the wishes of the community. The wheat, which was on the cars for shipment to North Carolina when I reached Rock Hill, and served the Agent with the notice, was unloaded and stored again in the depot. It may be there yet. At all events, it has not gone to North Carolina by railroad. But if the parties speculating knew the fact, they could ship it now. Gov. [Robert F. W.] Alston, Gov. [John Lawrence] Manning, [Franklin J.] Moses, and any others said that the Governor would not hesitate a moment. Gov. Manning said to McC. that if the governor hesitated, to copy the petition and address it to the Senate, and it would be received and acted upon immediately.

I merely bring this matter to your notice so that if you think it proper to continue the prohibition of wheat, you will know how matters stand. I see no use in putting a prohibition on corn or flour. The move however has kept wheat from advancing, which it was doing at the rate of 25 cents per day.

I will be glad to hear from you as often as convenient. Yours truly, — A. Whyte

1 This is a reference to Robin Jones’s Cavalry, which became Co. H of the 1st S. Carolina Cavalry, a.k.a, Black’s Regiment. Co. H. was composed of men from Rock Hill, SC in York District. According to the Yorkville Enquirer of February 13, 1862, the Company was organized the week before, on February 9, 1862, and left Rock Hill on February 12th. Capt. Robin Cadwallader Jones raised the Company and commanded it until he was killed on June 9, 1863 at the 1st Battle of Brandy Station, VA. One version asserted that he had captured several Union troopers, was collecting their weapons, and one of them shot him. Another version asserted that he attacked a dismounted trooper and cut off his thumb, but the wounded soldier managed to get off a fatal shot from his revolver as Capt. Jones rode past. James H. Barry succeeded him as Captain in September of 1863. He was wounded in the right foot on August 7, 1863 (incident not named) and part of his foot had to be amputated. He resigned on January 27, 1865 due to age and the fact that his three-year enlistment had expired on January 9, 1865. He then enrolled in the SC Reserves. It is not known who took over the company at that time.