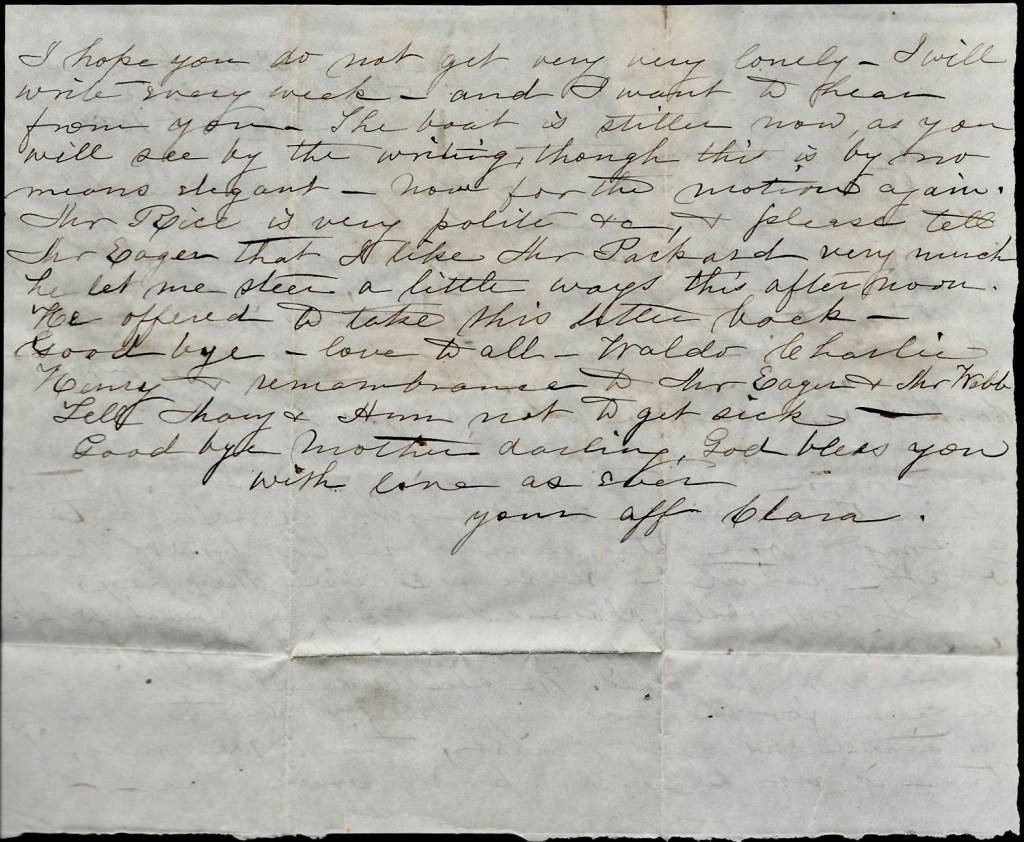

This letter was written by Clarissa (“Clara”) Dwight Marsh (1834-1899), the daughter of Henry Marsh, Jr. (1797-1852) and Sarah Whitney (1796-1883). Clara’s father was an 1815 graduate of Williams College and lived in Dalton, Massachusetts from 1821 to 1840 where he was a lawyer, a merchant, a farmer and wool grower, and a wool dealer and manufacturer. In 1840 he moved with his family to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he lost his savings with the failure of the Ashuelot Manufacturing Company. In 1843 he went to Racine, Wisconsin, in 1846 to Sandusky City, Ohio, and in 1850 to St. Louis, Missouri, engaging in the mercantile and produce business. He died of cholera in June 1852 but had managed to put three sons through Williams College and afforded his daughters, Clara, and Elizabeth (“Lizzie”) Willard Marsh (1829-1882), some outstanding educational advantages as well.

Lizzie “was educated at Maplewood, Pittsfield, Mt. Holyoke and Bradford Seminaries, and spent her life in teaching. She had a school in St. Louis and at Batavia, Illinois, and afterwards taught in private families in Pittsfield, Mass., Batavia, N. Y., and Hudson, Wisconsin. At the latter place on Lake St. Croix she made her home with her life-long friend, Susan (“Sue”) Ellen Lockwood (1830-1915), the wife Charles Wendell Porter and the daughter of Judge [Samuel Drake] Lockwood of Batavia, Illinois. She died at Hudson, Wisconsin, on 23 April 1882.”

Clara attended the Cooper Female Academy in Dayton, Ohio, in the early 1850s. She married Samuel Watkins Eager, Jr. of St. Louis, Missouri, in May 1857.

Clara does not state her destination in this letter but she was clearly heading east—or up-river—on the Illinois river on her way from St. Louis to LaSalle, Illinois, where we learn she expected to catch the Illinois Central railroad to Chicago and from there to points East. Most likely she was going east to the Cooper Female Academy in Dayton, Ohio. In those days, young ladies did not travel alone so she was probably being escorted by the “Mr. Rice” who is mentioned in the letter.

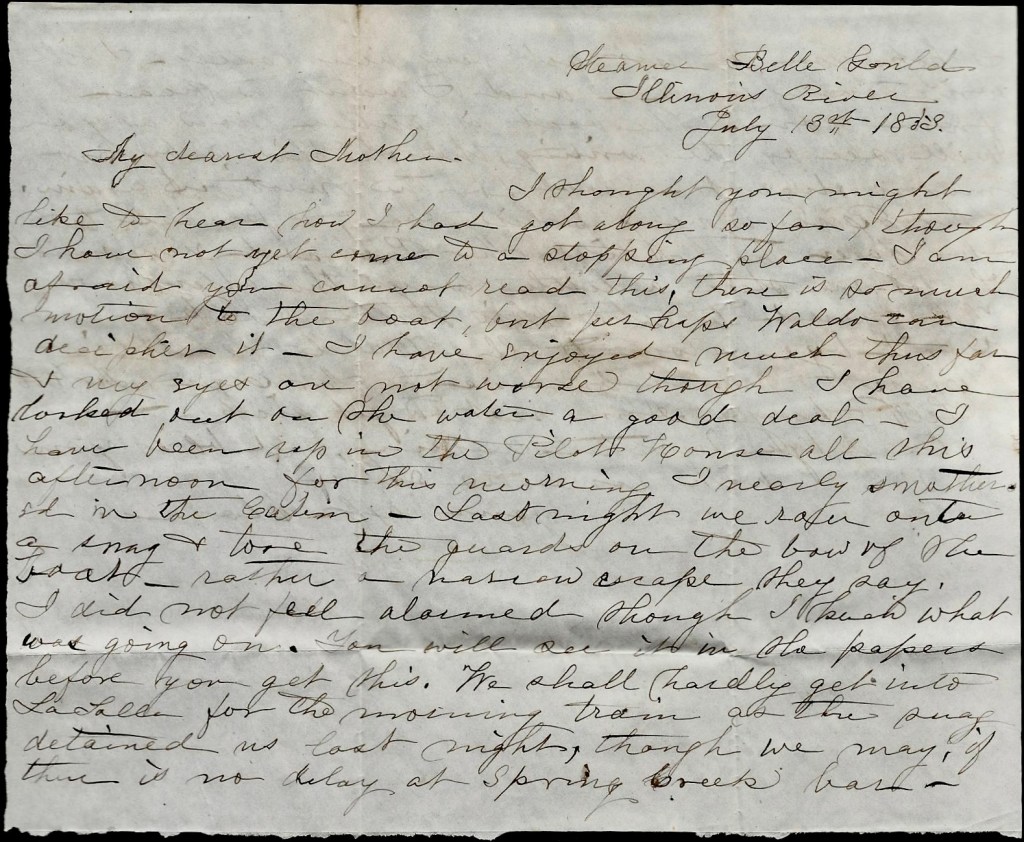

Transcription

Steamer Belle Gould 1

Illinois River

July 13th 1853

My dearest Mother,

I thought you might like to hear how I had got along so far though I have not yet come to a stopping place. I am afraid you cannot read this, there is so much motion to the boat, but perhaps [brother] Waldo can decipher it. I have enjoyed much thus far & my eyes are not worse though I have looked out on the water a good deal. I have been up in the pilot house all this afternoon for this morning I nearly smothered in the cabin.

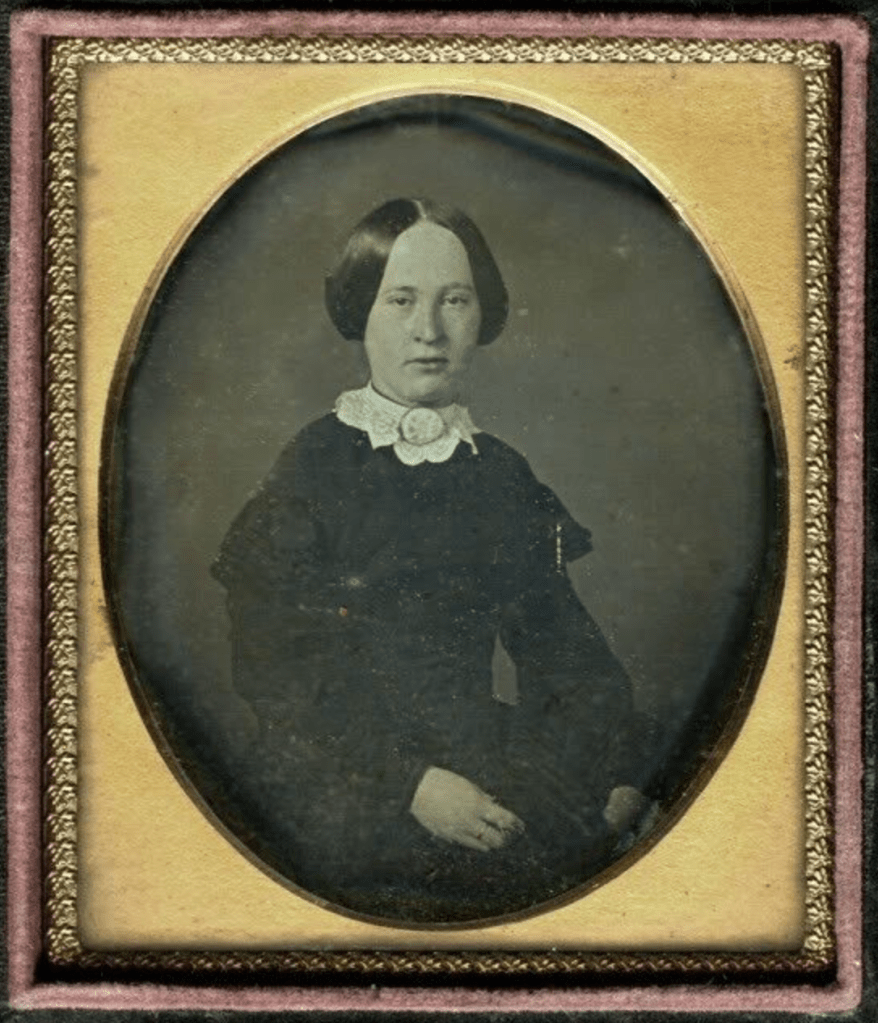

Last night we ran onto a snag & tore the guards on the bow of the boat—rather a narrow escape they say. I did not feel alarmed though I knew what was going on. You will see it in the papers before you get this. We shall hardly get into LaSalle for the morning train as the snag detained us last night, though we may if there is no delay at Spring Creek bar.

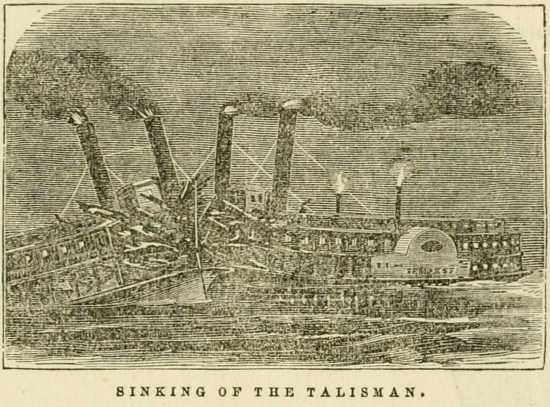

I hope you do not get very very lonely. I will write every week and I want to hear from you. The boat is stiller now, as you will see by the writing though this is by no means elegant. Now for the motion again.

Mr. Rice is very polite &c., and please tell Mr. Eager that I like Mr. Packard 2 very much. He let me steer a little ways this afternoon. He offered to take this letter back. Goodbye. Love to all—Waldo, Charlie, Henry, & remembrance to Mr. Eager and Mr. Webb. Tell Mary and Ann not to get sick. Goodbye Mother darling. God bless you. With lover as ever, your affectionate Clara

1 The Belle Gould was a side-wheel steamboat built in New Albany, Indiana, in 1852 for the St. Louis-Keokuk trade. She ran the Illinois River in 1853 and was the first steamboat to arrive in Peoria. She was snagged and sank at Island 25 below Cairo, Illinois on 3 March 1854.

2 I believe “Mr. Packard” may have been Capt. Bryant Rogers Packard (1821-1869) who was a steamboat captain residing at 1409 Papin Street in St. Louis, Missouri. He named his daughter “Belle Gertrude Packard (1858-1864).”