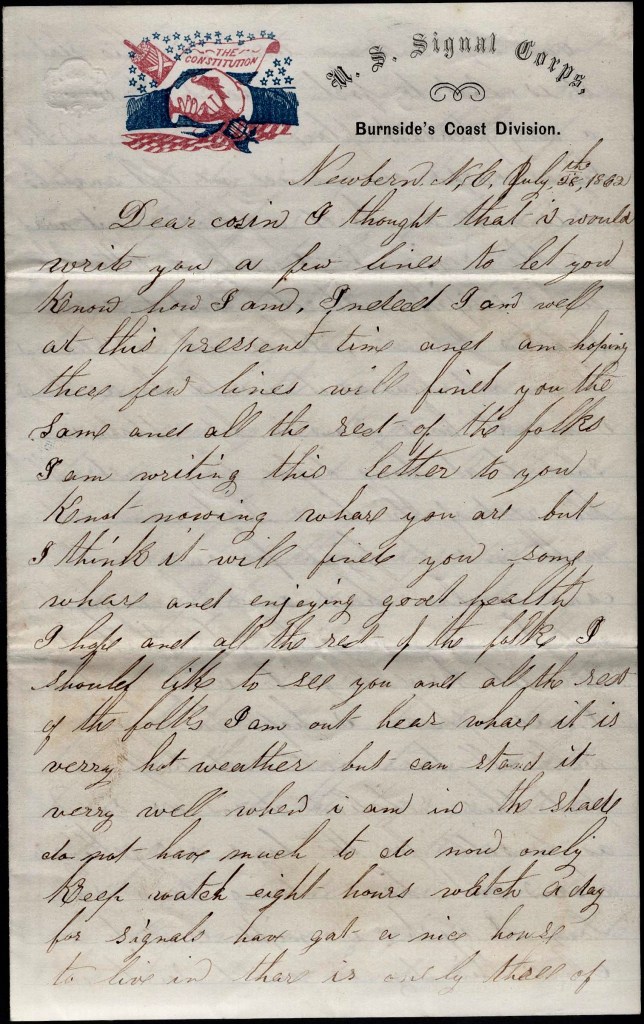

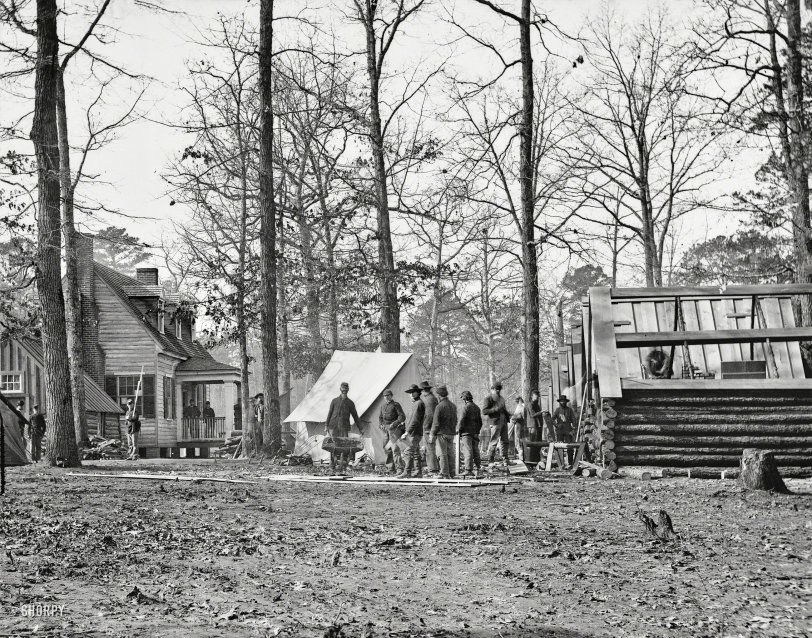

The following letter was only signed “John” and leaves us with too few clues to confirm his identity but he was most certainly a member of the U. S. Signal Corps attached to Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James which was encamped on Bermuda Hundred.

“Although telegraphy was used extensively during the Petersburg campaign, signal trees, towers and buildings remained vital tools for each army to observe the movements of the enemy from an elevated vantage point. Information gained from such observations could then be relayed through all available means of communication, including signaling by flag or torch. Military uses of these locations included artillery spotting, mapping, and photography. The fourth estate also climbed these posts as special artists drew the siege lines and battlefields and reported war news.”

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

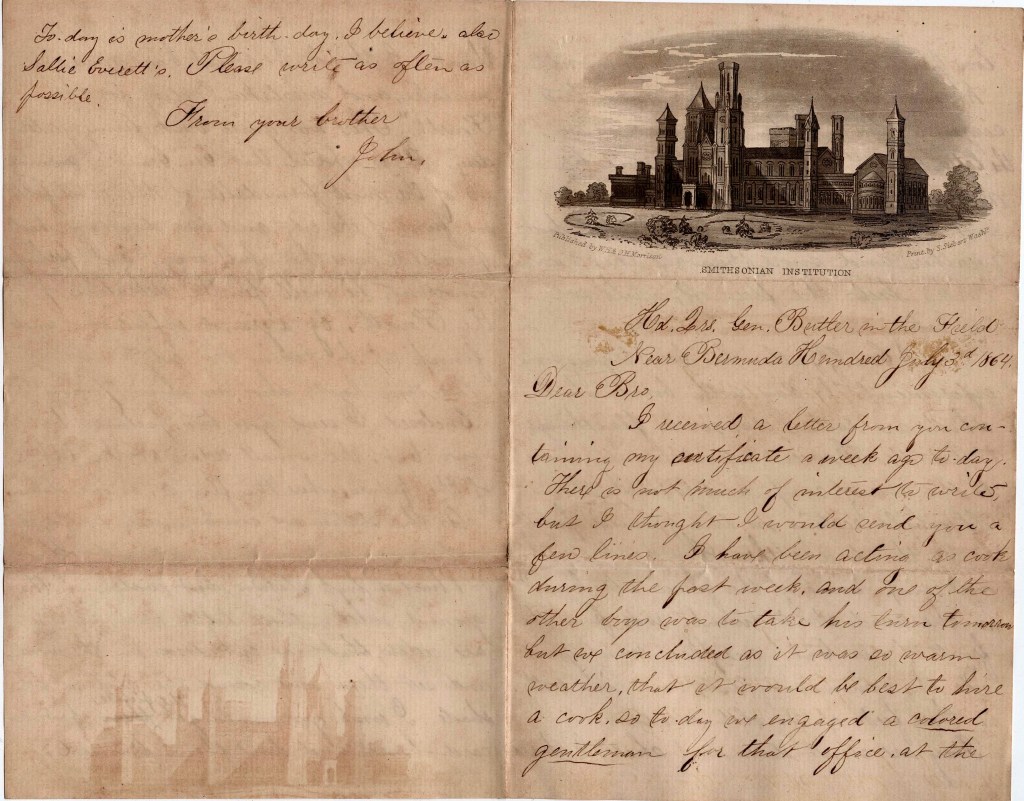

Headquarters Gen. Butler in the Field

Near Bermuda Hundred

July 3rd 1864

Dear Brother,

I received a letter from you containing my certificate a weeks ago today. There is not much of interest to write but I thought I would send you a few lines.

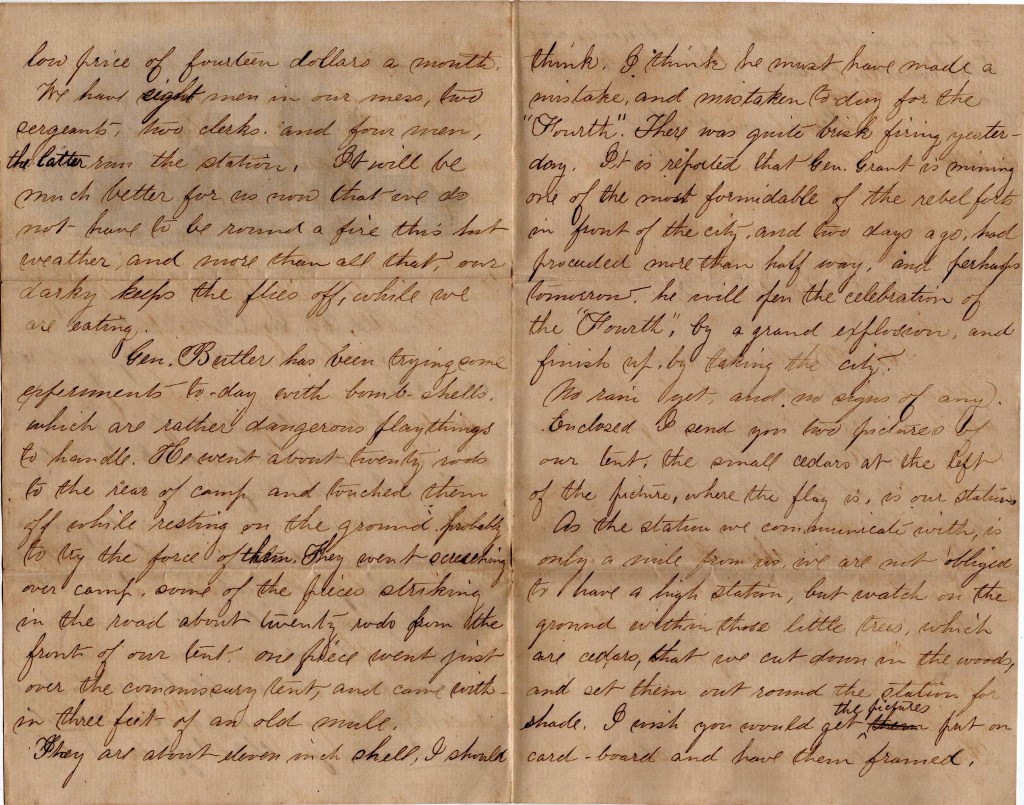

I have been acting as cook during the past week and one of the other boys was to take his turn tomorrow but we concluded as it was so warm weather that ut would be best to hire a cook, so today we engaged a colored gentleman for that office at the low price of fourteen dollars a month. We have eight men in our mess—two sergeants, two clerks, and four men. The latter run the [signal] station. It will be much better for us now that we do not have to be round a fire this hot weather and more than all that, our darky keeps the flies off while we are eating.

Gen. [Benjamin F.] Butler has been trying some experiments today with bomb shells which are rather dangerous play things to handle. He went about twenty rods [110 yards] to the rear of camp and touched them off while resting on the ground, probably to try the force of them. They went screeching over camp, some of the pieces striking in the road about twenty rods from the front of our tent. One piece went just over the commissary tent and came within three feet of an old mule. They are about eleven inch shell, I should think. I think he must have made a mistake and mistaken today for the “Fourth.”

There was quite brisk firing yesterday. It is reported that Gen. Grant is mining one of the most formidable of the rebel forts in front of the city and two days ago had proceeded more than half way 1 and perhaps tomorrow he will open the celebration of the “Fourth” by a grand explosion and finish up by taking the city.

No rain yet and no signs of any. Enclosed I send you two pictures of our tent. The small cedars at the left of the picture, where the flag is, is our station. As the station we communicate with is only a mile from us, we are not obliged to have a high station, but watch on the ground within those little trees, which are cedars, that we cut down in the woods and set them out round the station for shade. I wish you would get the pictures put on cardboard and have them framed.

Today is mother’s birthday. I believe also Sallie Everett’s. Please write as often as possible. From your brother, — John

1 Digging the mine for the Battle of the Crater started on June 25, 1864. The Union miners, primarily from the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, including many experienced coal miners, made rapid progress, sometimes digging 40 feet a day. By July 17, 1864, they had excavated a shaft reaching 511 feet (510.8 feet according to one source), bringing the mine to a point 20-22 feet below the Confederate position at Elliott’s Salient. Although the exact date when the mine was “half done” is not specified, it can be inferred from the available information that the main shaft, which extended under the Confederate lines, was approximately completed by mid-July, around July 17th. The lateral tunnel was then dug and completed by July 23rd, and the mine was packed with explosives by July 27th. The explosives were detonated on the morning of July 30, 1864.