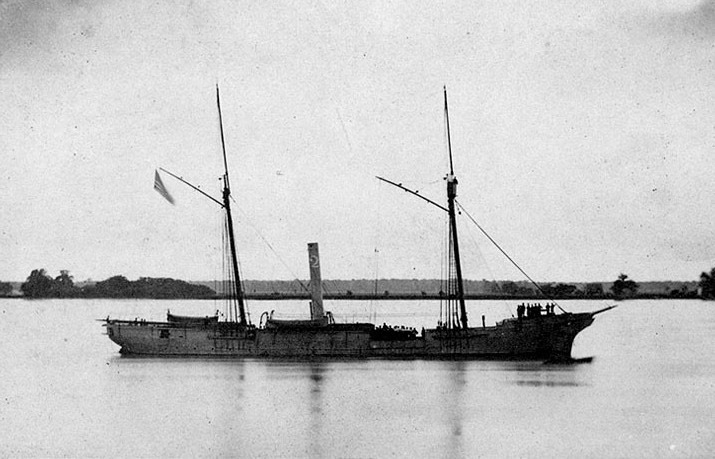

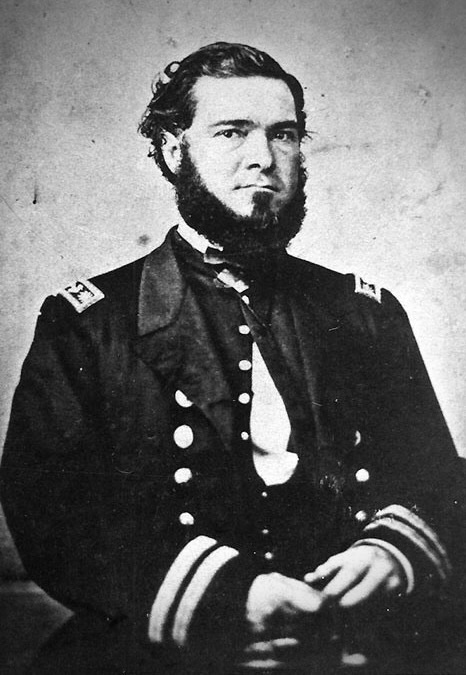

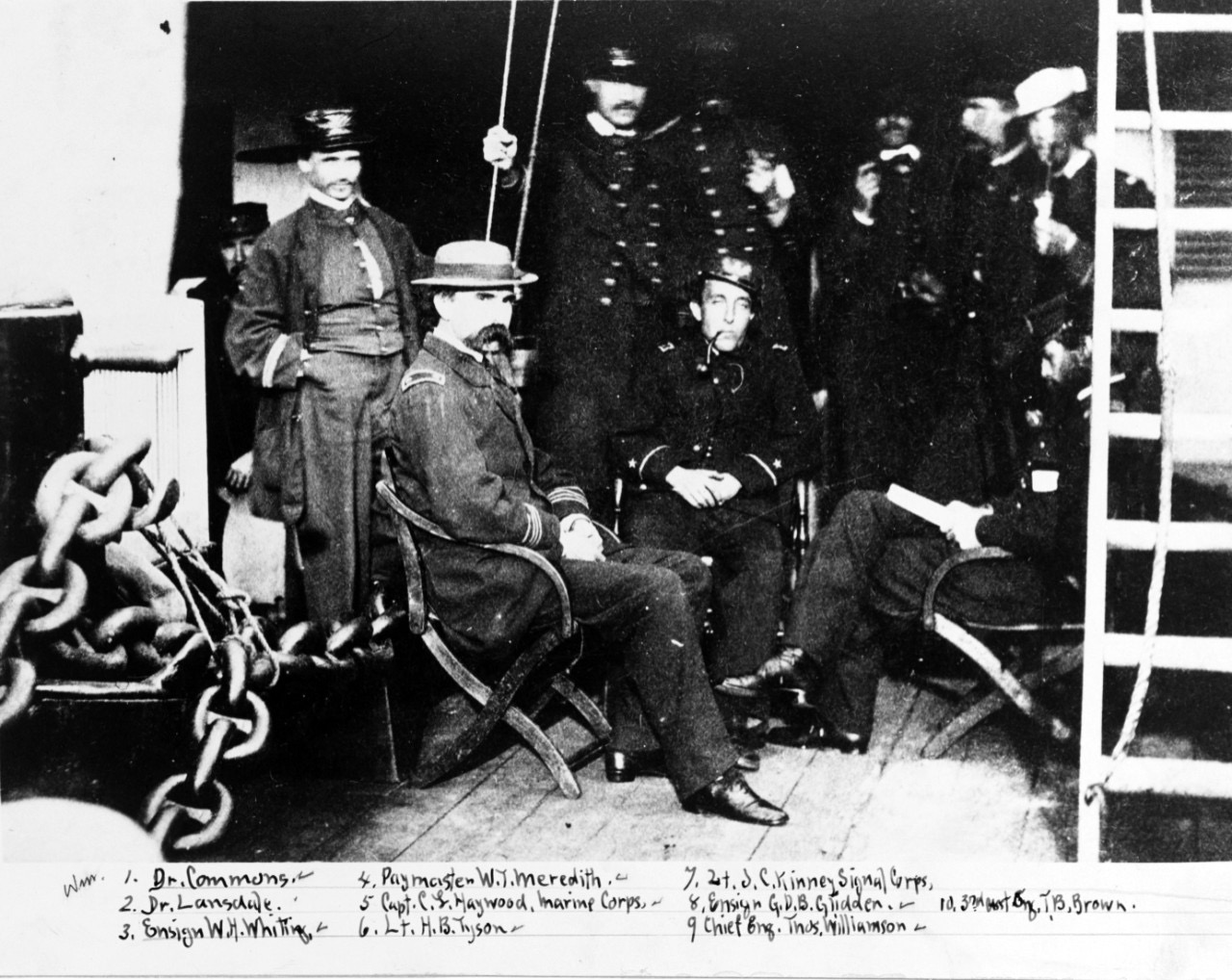

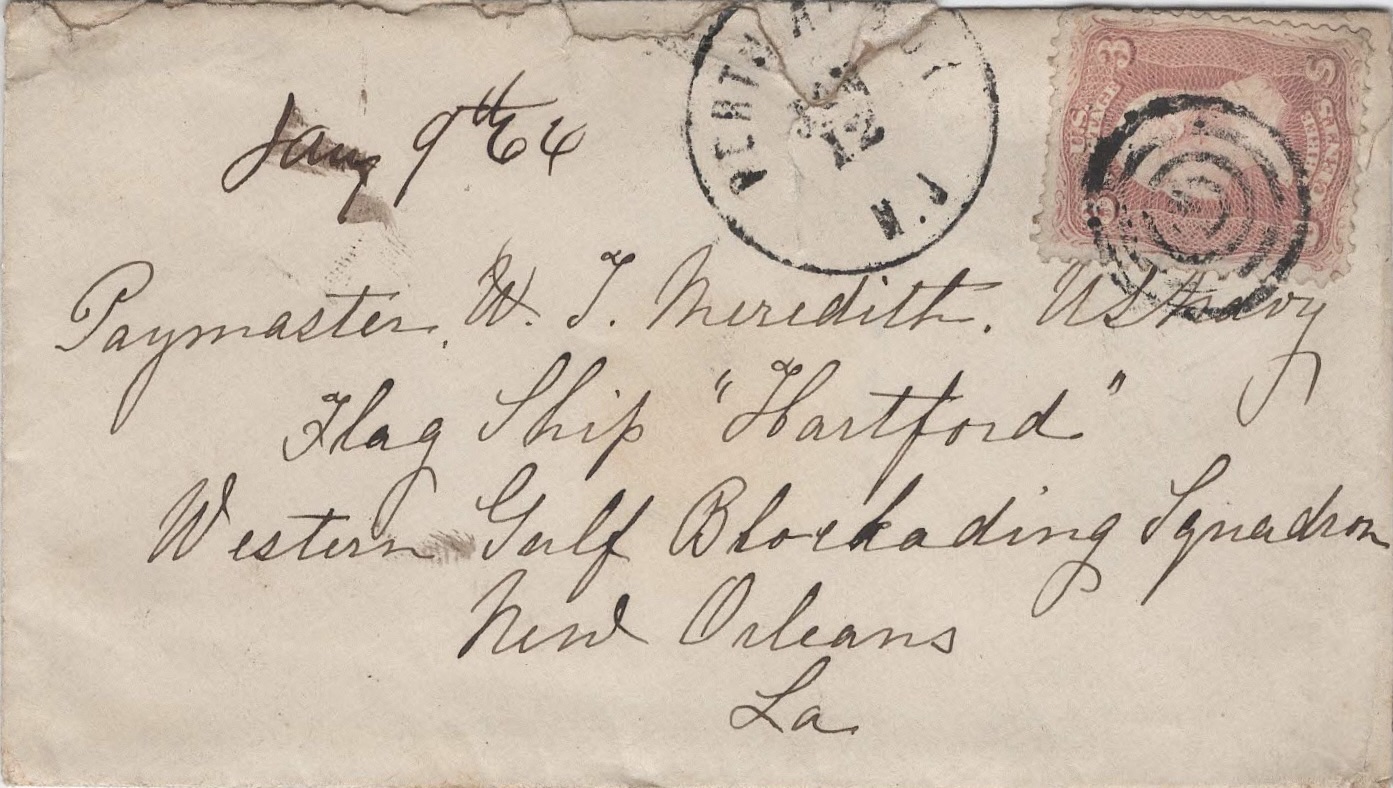

The following letter was written by US Navy Assistant Paymaster William Tuckey Meredith (1839-1920) who received his appointment from President Abraham Lincoln in September 1861 and was eventually assigned to serve under “Damn the Torpedoes” Admiral David Farragut aboard the USS Hartford—the Admiral’s flagship.

William was the son of Joseph Dennie Meredith (1814-1856) and Sarah Emlen Scott (1818-1909) of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. William (or “Willie”) was named after his grandfather (died in 1844) who was a successful attorney and president of the Schuylkill Bank. Willie’s uncle was William Morris Meredith, a Whig, who served as the Attorney General of Pennsylvania and as the 19th US Secretary of the Treasury under President Zachery Taylor.

Willie’s letter informs his mother of a recent passage down the Mississippi to New Orleans and of his return to the Flagship USS Hartford. He tells her of being fired on by Confederate guerrillas near Donaldsonville, Louisiana, and that he is convinced commerce cannot be safely restored simply by capturing Vicksburg and Port Hudson.

After the war Meredith would write poetry including the poem “Farragut” memorializing the taking of Mobile Bay by Farragut’s fleet in August 1864.

“Farragut”

Mobile Bay, 5 August, 1864, by William Tuckey Meredith

FARRAGUT, Farragut,

Old Heart of Oak,

Daring Dave Farragut,

Thunderbolt stroke,

Watches the hoary mist

Lift from the bay,

Till his flag, glory-kissed,

Greets the young day.

Far, by gray Morgan’s walls,

Looms the black fleet.

Hark, deck to rampart calls

With the drums’ beat!

Buoy your chains overboard,

While the steam hums;

Men! to the battlement,

Farragut comes.

See, as the hurricane

Hurtles in wrath

Squadrons of clouds amain

Back from its path!

Back to the parapet,

To the guns’ lips,

Thunderbolt Farragut

Hurls the black ships.

Now through the battle’s roar

Clear the boy sings,

“By the mark fathoms four,”

While his lead swings.

Steady the wheelmen five

“Nor’ by East keep her,”

“Steady,” but two alive:

How the shells sweep her!

Lashed to the mast that sways

Over red decks,

Over the flame that plays

Round the torn wrecks,

Over the dying lips

Framed for a cheer,

Farragut leads his ships,

Guides the line clear.

On by heights cannon-browed,

While the spars quiver;

Onward still flames the cloud

Where the hulks shiver.

See, yon fort’s star is set,

Storm and fire past.

Cheer him, lads—Farragut,

Lashed to the mast!

Oh! while Atlantic’s breast

Bears a white sail,

While the Gulf’s towering crest

Tops a green vale,

Men thy bold deeds shall tell,

Old Heart of Oak,

Daring Dave Farragut,

Thunderbolt stroke!

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

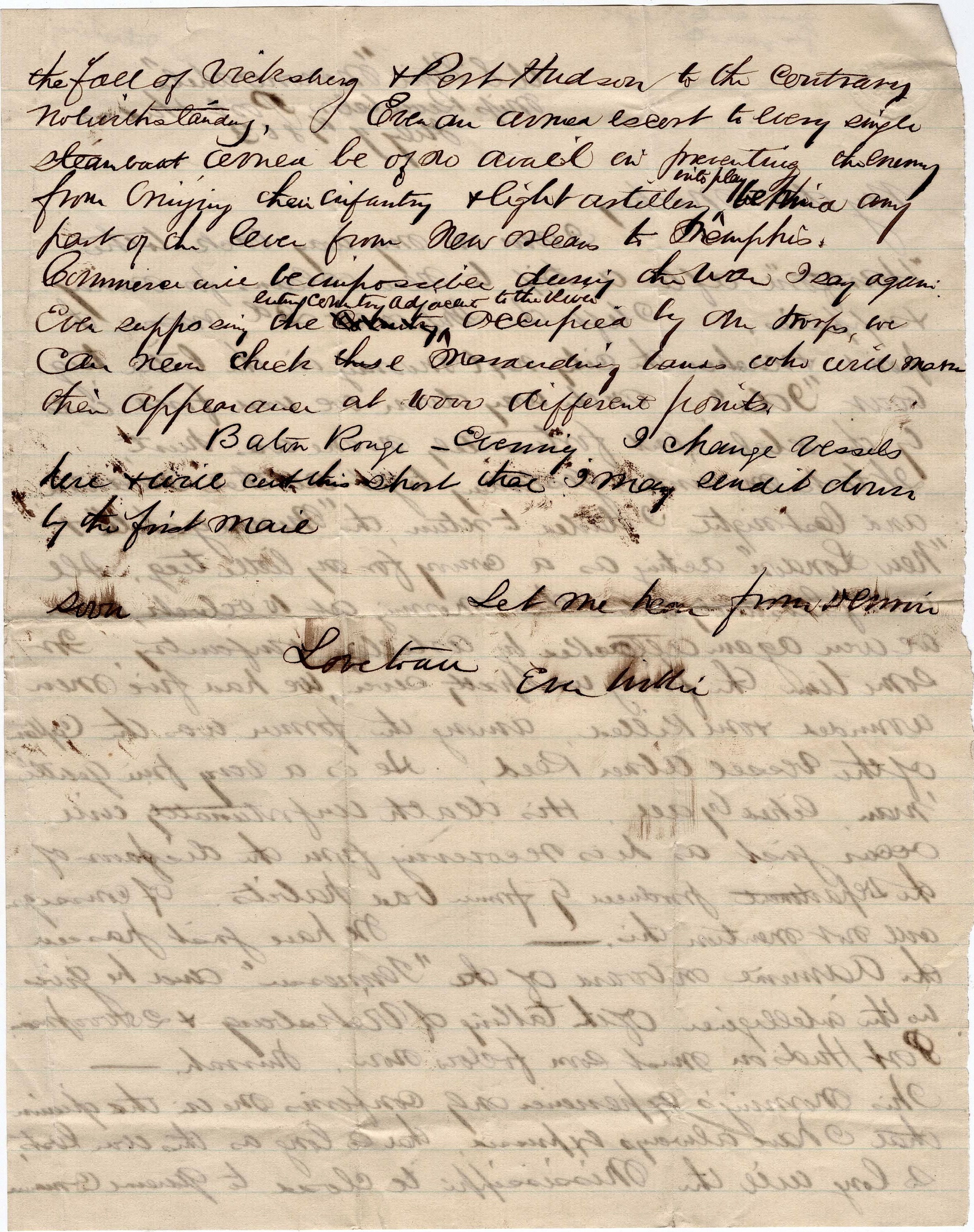

U. S. Steamer Monongahela

Mississippi River below Port Hudson

July 7th 1863

My dear Mother,

I am on my way back to the Hartford after a trip to New Orleans for money & supplies. I left the ship on the 2d, crossed the point and reached the city next morning in the little tug boat Ida. On the way down we were fired into by the rebels but fortunately no one was hurt. It took me until yesterday to get all that I wanted and last night I started to return, the Monongahela and New London acting as convoy for my little tug. All went pleasantly until this morning at 10 o’clock when we were again attacked by artillery & infantry. For some time the firing was pretty severe. We had five men wounded and one killed. Among the former was the captain of the vessel, Abner Reed. He is a very fine gentleman, liked by all. His death unfortunately will occur just as he is recovering from the disfavor of the Department produced by former bad habits. Of course you will not mention this. 1

We have just passed the Admiral on board of the Tennessee and he gives us the intelligence of the taking of Vicksburg & 25,000 prisoners. Port Hudson must soon follow now. Hurrah!

This morning’s experience only confirms me in the opinion that I have always expressed, that as long as this war lasts, so long will the Mississippi be closed to general commerce, the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson to the contrary notwithstanding. Even an armed escort to every single steamboat could be of no avail in preventing the enemy from bringing their infantry and light artillery into play behind any part of the levee from New Orleans to Memphis. Commerce will be impossible during the war. I say again, even supposing the country adjacent to the river be occupied by our troops, we can never check these marauding bands who will make their appearance at 10,000 different points.

Baton Rouge. Evening. I change vessels here and will cut this short that I may send it down by the first mail. Let me hear from home. Love to all.

Ever, — Willie

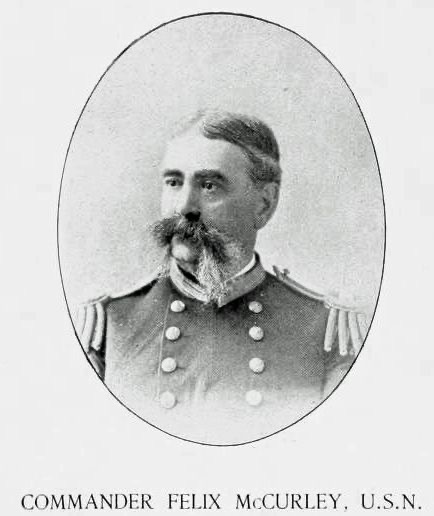

1 Willie clearly gives the commander of the tug as Abner Reed but this surname is either misspelled or other official records are in error for he most certainly was the same Abner Read (1821-1863) who’s career is thoroughly laid out in the following Wikipedia biography—See Abner Read — and whose death is reported as: On the morning of July 7, 1863, Southern forces opened fire on the ship with artillery and musketry when she was about ten miles below Donaldsonville. A shell smashed through the bulwarks on her port quarter [says USS Monongahela] wounding Read in his abdomen and his right knee. He was taken to a hospital at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he died on the evening of the next day.“

In an article appearing in the New York World on 20 July 1863 under the heading “On the River,” it was stated that, “Last week there was but one rebel battery on the river below Donaldsonville—now there are three, viz. one three miles below that place; a second at College Point, twenty miles nearer this city; and a third ten miles below and nearer New Orleans than College Point, armed, as represented, with smooth9-pound and rifled 10-pound guns. Scarcely a boat going up or down has escaped a shot from some or all of these batteries. The St. Mary, the Monongahela, all the river boats, tugboats, steamboats, and what not, have been fired at, and some of them have been hit. The gunboat Monongahela, July 8, received six shots, one of which disemboweled her commander, Abner Reed, who has since died, and another man on board was killed. For a quiet river, it is a singular state of things, surely. The levee furnishes a ready-made earthwork, the embrasures are dug, and it is said that negroes are collected on the top of the levee for the gunboats to fire at in return, if they choose. The water is so low in the river that it is almost impossible for the gunboats to fire at the batteries with any effect, while the batteries have every advantage…”