These letters were written by Reuben T. Swain, the son of Capt. Henry Swain (1776-Bef1850) and Elizabeth A. Townsend of Cape May, New Jersey. Unfortunately I cannot find any record of Reuben serving in the US Navy but his letters indicate that he lost a leg while in the Navy and that he recuperated at the U. S. Naval Asylum in Philadelphia. He would have been a pretty old sailor as I believe he was born before 1810. He may have been the same Rueben T. Swain who was named as a runaway indentured apprentice by Richard Powell who was in the Philadelphia cabinet making business and offered a reward of “six cents” for his return. That advertisement appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer in 13 July 1831 and may coincide with Reuben’s enlistment in the U. S. Navy. He would have been 21 at the time and he was indeed an indentured servant runaway, he may have enlisted under another name.

We learn from his letters that Reuben had never previously married and it appears he spent his entire life at sea—possibly launching out of Savannah for some years.

Reuben wrote the letters to his nephew, Jesse Diverty Ludlam (1840-1909), the son of Christopher Ludlam (1796-1861) and Hannah Swain (1802-1882). Jesse was married in November 1861 to Emily Cameron Miller (1841-1912) and employed principally as a farmer in Cape May county.

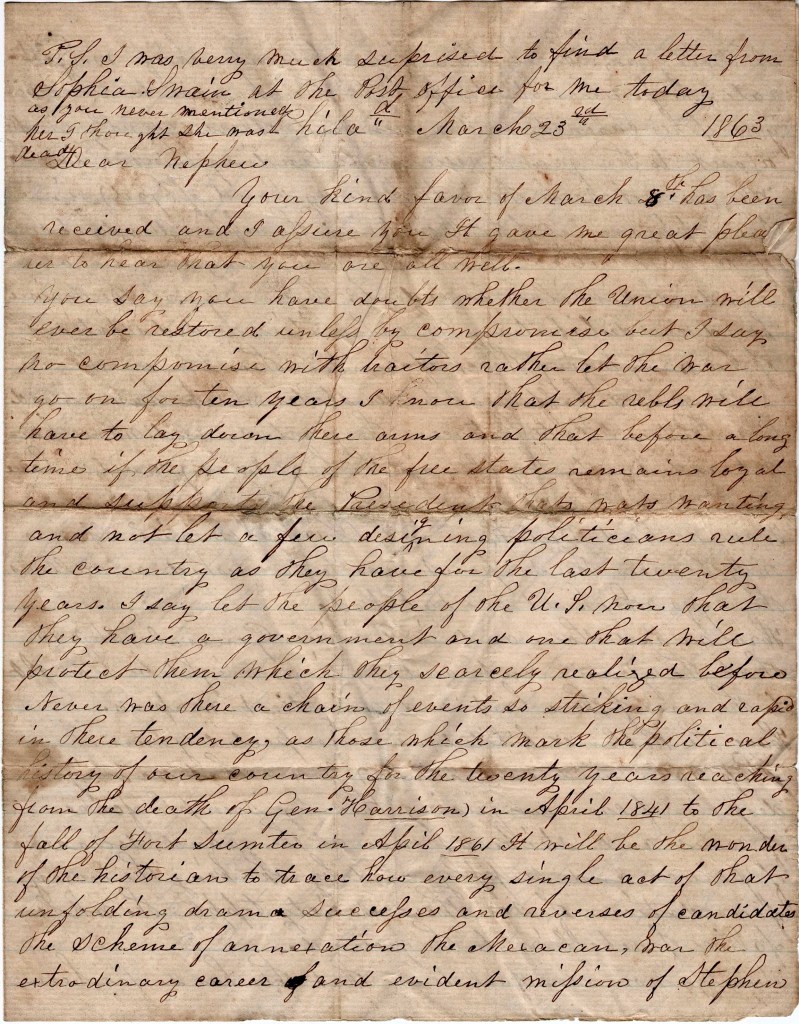

Letter 1

Philadelphia [PA]

March 23, 1863

Dear Nephew,

Your kind favor of March 8th has been received and I assure you it gave me great pleasure to hear that you are all well.

You say you have doubts whether the Union will ever be restored unless by compromise, but I say no compromise with the traitors. Rather let the war go on for ten years. I know that the rebels will have to lay down their arms and that before a long time if the people of the free states remain loyal and support the President. That’s what’s wanting, and not let a few designing politicians rule the country as they have for the last twenty years. I say let the people of the U. S. now that they have a government and one that will protect them which they scarcely realized before.

Never was there a chain of events so striking and rapid in their tendency as those which mark the political history of our country for the twenty years reaching from the death of Gen. Harrison in April 1841 to the fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861. It will be the wonder of the historian to trace how every single act of that unfolding drama, successes and reverses of candidates, the scheme of annexations, the Mexican War, the extraordinary career and evident mission of Stephen A. Douglas, the election of our present chief magistrate, the peculiar blindness of Mr. Buchanan to the designs of his cabinet, and a hundred other equally important to the grand result all tending this one issue.

Who has not seen the interposing hand of God in the appearance of the Monitor in Hampton Roads at one of the most critical moments of the war, and in a hundred similar incidents? How signal the divine hand in distributing the calamities and desolations of the war, laying the chief burden thus far on the halting and half loyal border states which have stood Pontius Pilate between the parties, and whose prompt and hearty loyalty in the beginning would have averted this war.

Have we had Bull Runs and Chickahominies—it was only because the serpent was to be crushed as well as the eggs which it has hatched. Have we had slow and decisive Generals—it was that the Government and Nation might be brought to the use of their last and weightiest weapons. Have the Rebels exhibited an unexpected generalship, valor and endurance—it was that we might despair of ever conquering them by simple force of arms and strike at once at the grand source of power and supply, and by shaking the very foundations of southern society society topple the whole fabric of rebellion to the ground.

Surely, none can fail to see that this has so far been the result toward which all the incidents of the struggle have conspired and that two with a uniformity and a constant baffling of human plans and expectations which evince an overruling hand.

This war shall prove a blessing, not only to our country, but the race in the ultimate and utter extinction of chattel slavery in this banner land of freedom, where it must be destroyed before the world can be free. I confess that they are not the means which should have been chosen, nor are they the means which God would have chosen had we been willing to cooperate with him. The offering should have been a voluntary one to God and the oppressed race.

But this the dream of Washington and the counsel of Jefferson and the labor of Franklin and Adams, and the confident expectations of all the Fathers of our Republic was not to be the shame of their degenerate sons be it spoken. And as we would not draw Gods chariot of liberty and progress, it has passed on to its goal of triumph over our prostrate forms.

You must not think Jesse, that I am a friend to the negro—far from it. I wish they were all in Africa where they belong. But you may rely that it was slavery that brought the country to this war and the extinction of slavery will be the end of this war and the Union preserved. I would sooner see this war last for years than to see those accursed traitors gain their ends.

What a sin lies at the door of hypocritical England for this loss of blood and treasure. You might have a different opinion, but I do honestly believe that the beginning of this war was mainly encouraged by the aristocracy of that bigoted race. You might blame me for being so down on that Nation, but I feel at present such a burning hatred for that Nation which has been the cause of our present trouble [and] that if I had children, after learning them to lisp their prayers, I would add a curse on that cross of St. George. What would they have done during that Trent Affair if Seward would have left a shadow of chance? They would have gloried in the downfall of freedom on this continent. But thank God we have a Navy now that they have every reason to dread. Our ironclads have caused such a revolution in the naval history of the world as was never dreamed of.

Jess, this difficulty cannot be settled by compromise otherwise than to let them go, and if they go, every state in the Union has the same right, and in a short time the U. S. would be cut up into small republics and none of them able to protect themselves. The next thing would be some European power would have to protect them and that would be worse than death to every true American. No, we have a government and a good one too. And let us support it and all will end well yet.

I must close as it is getting so dark that I can scarcely see. I remain your friend, — Reuben T. Swain, Philadelphia

to Jesse D. Ludlum, Dennisville, N. J.

P. S. I was very much surprised to find a letter from Sophia Swain at the Post Office for me today. As you never mentioned her, I thought she was dead.

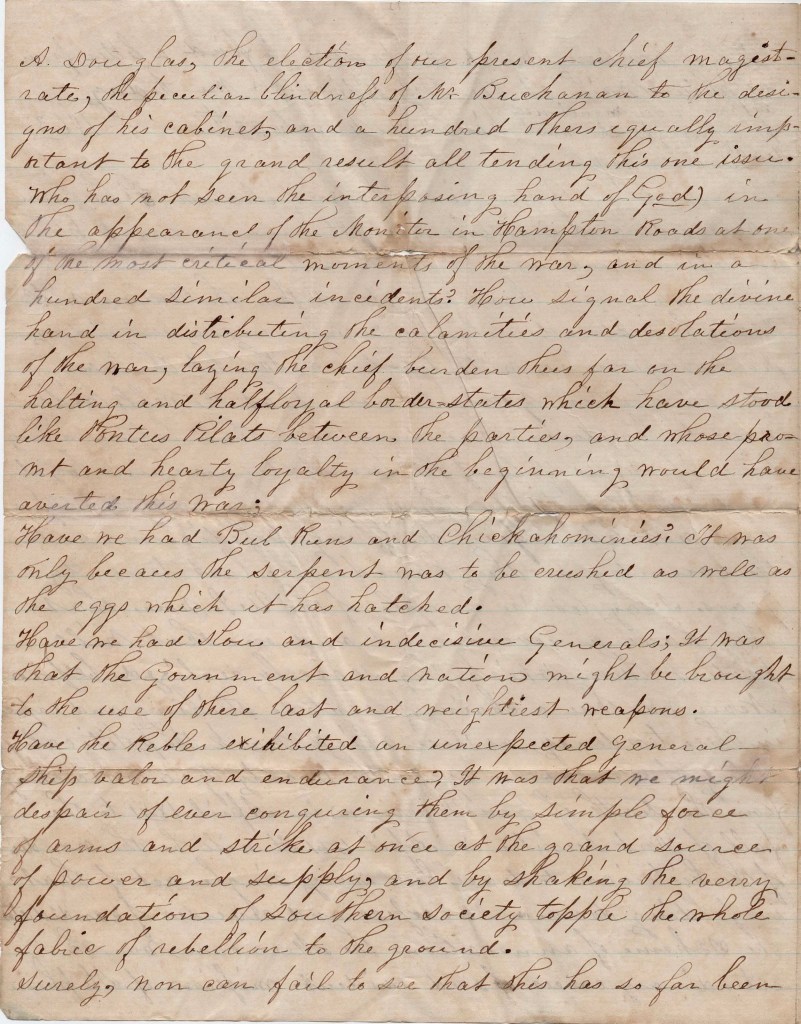

Letter 2

Note: This letter is from the personal collection of Greg Herr and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.

U. S. Naval Asylum

Philadelphia, [Penn.]

June 17, 1863

Dear Nephew,

I embrace the present opportunity of writing to you and to inform you that I will start for Dennisville on the 2nd of July, provided no unforeseen occurrence prevents. I suppose you will think that I want a great deal of coaxing but it is not so. There is nothing that would give me so much pleasure as to see Hannah and the children. I should have been to see you before only I expected to get a new artificial limb made before coming. There seems to be a great demand for the article at present and I could not get one made before the last of August so I concluded to come on the old one. I make a poor [job] out walking on the old one and are afraid that I will be in the way very much.

Oh! I saw Joshua and was surprised to see so large a man. It seems only the other day that he was a little boy. Oh how I wish I had my other understanding and I would be off to sea again and take Joshua with me to see foreign countries. But those days are passed and gone and I must be content myself within the limits of the United States, I suppose.

The letter you sent to the Philadelphia Post Office I have received. It was from Priscilla. They are all well and complain that they cannot hear from Dennisville. I should like to see Priscilla, and Robert. 1 Poor fellow! I suppose we will never see him again. Robert’s case is a hard one and I suppose he is secesh. We must make allowances for him under existing circumstances. He was a citizen of Louisiana. All his property was there. Also married, his wife’ heirs, and she belonged there, and woman has great influence over man you know—at least I suppose so. Why! if I had been married in Savannah, I suppose I would have been secesh too! But woman or no woman, I never would have consented to fight against the Stars and Stripes. I have sailed too long under the starry banner of our country to desert it in hour of danger.

Elizabeth Swain is coming down with me. I expect Sophia and Lib are well. Dick Townsend I have not seen for a long time.

The war news is so conflicting that I will say nothing about it, as I expect you get the same news as we have here—only that I wish the Abolitionists and the Niggers were pitted together and had to fight it out against the fire-eaters of the South, and I would be willing to abide the issue.

So I will close by adding my respects and best wishes for all of your present and future welfares, hoping soon to see you all.

P. S. If the weather proves unfavorable, I will postpone until good weather. Yours respectfully, — Reuben T. Swain, Philadelphia

To Jesse D. Ludlam, Dennisville, Cape May, N. Jersey

I have just seen an advertisement in the Philadelphia papers that the cars will commence running on the Cape May and Millville Railroad on and after the 22nd of June, to the Dennisville Station. So you may expect me on the 2nd of July. — R. T. Swain

I should have come down sooner but I just received a letter from Washington saying in answer to my application for a leave of absence that it cannot be granted until the first of the month. I suppose you will think strange that I am under Government orders but I will explain when I come. So you may expect me July 2nd 1863 Your Uncle, — R. T. Swain

1 I believe this is a reference to Reuben’s brother, Richard Swain (1800-1871) who married Anna Matilda McClure (18xx-1884) and was a resident of New Orleans when the Civil War began. He was employed as a ship inspector. Richard’s son, Richard D. Swain (1839-1900) was a 2nd Lt. in Co. E, 5th Louisiana Infantry (CSA) during the war. He spent some time at Johnson’s Island Prison after he was captured at Rappahannock Station in November 1863.

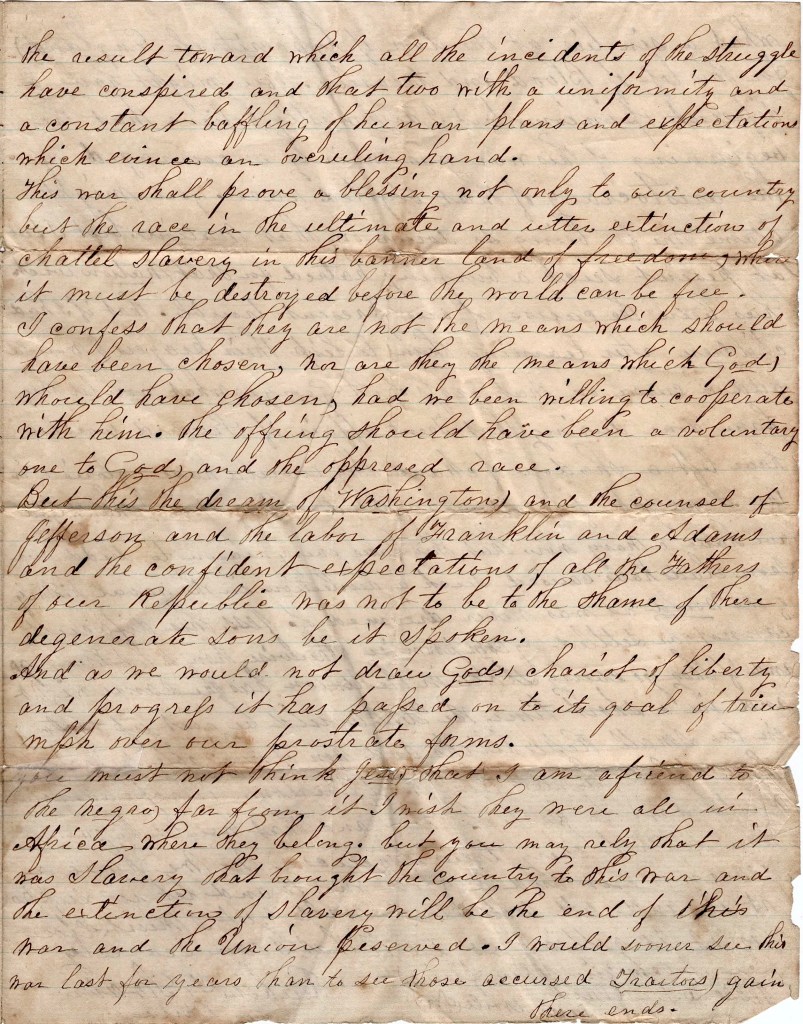

Letter 3

U. S. Naval Asylum, Philadelphia

April 18, 1864

Mrs. Emily C. Ludlum, dear Madam,

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication of the 17th inst. enclosing your thanks and opinions of the ship. I feel very much flattered and complimented at the honor conferred on me, and pleased you think it worth mentioning, yet sorry you should think it give me trouble. It is hardly necessary for me to assure you that rather than trouble, it gives me pleasure, and passed away many lonesome hours. You complain that everything is so high. Of this fact I am well aware and see no prospects of a change as long as this war continues. But I have hopes that the end is nigh. I suppose you will say you cannot see any prospects of the end being nigh and ask me to explain why I think there is prospects of the end being nigh. Well, I will give you my poor opinion and leave it to your option to form any idea you like on it.

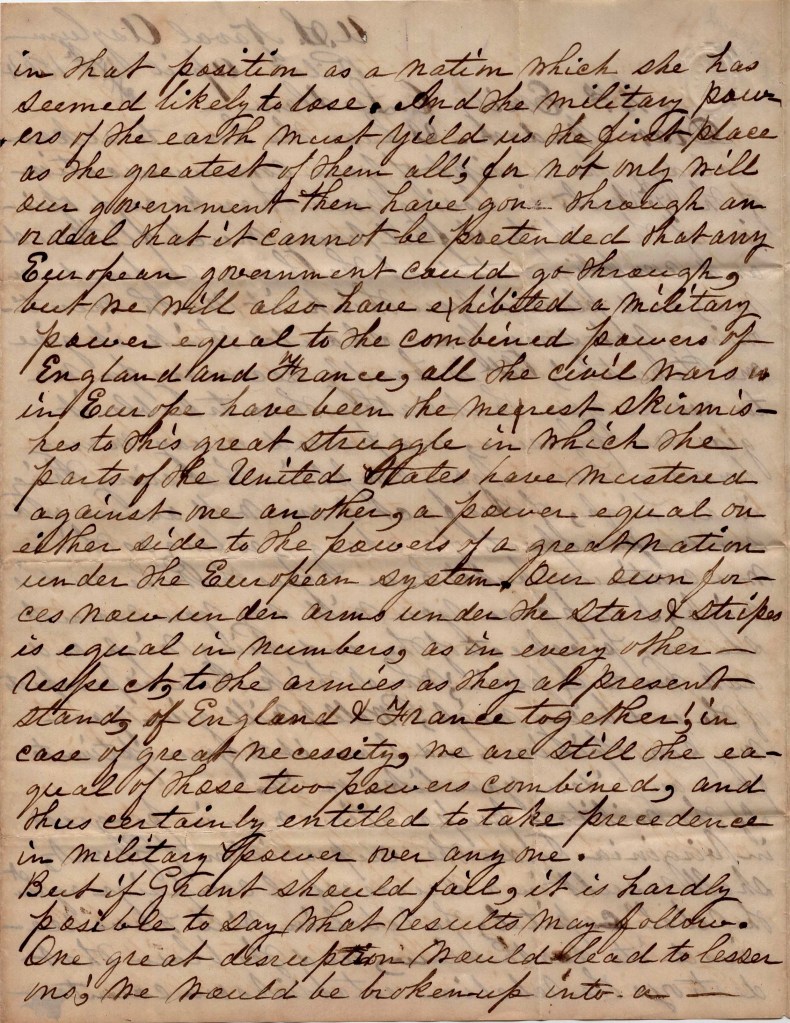

If the military preparations now in progress in Virginia under the supervision of Grant shall result in a successful campaign against the rebel capitol, the rebellion will have received its death blow, and the blow that destroys the rebellion establishes our country in that position as a nation which she has seemed likely to lose. And the military powers of the earth must yield us the first place as the greatest of them all, for not only will our government then have gone through an ordeal that it cannot be pretended that any Eurpopean government could go through, but we will also have exhibited a military power equal to the combined powers of England and France. All the civil wars in Europe have been the merest skirmish to this great struggle in which the parts of the United States have mustered against one another—a power equal on either side to the powers of a great nation under the European system.

Our own forces now under arms under the stars and strips is equal in numbers, as in every other respect, to the armies as they at present stand, of England & France together! In case of great necessity, we are still the equal of those two powers combined and this certainly entitled to take precedence in military power over anyone.

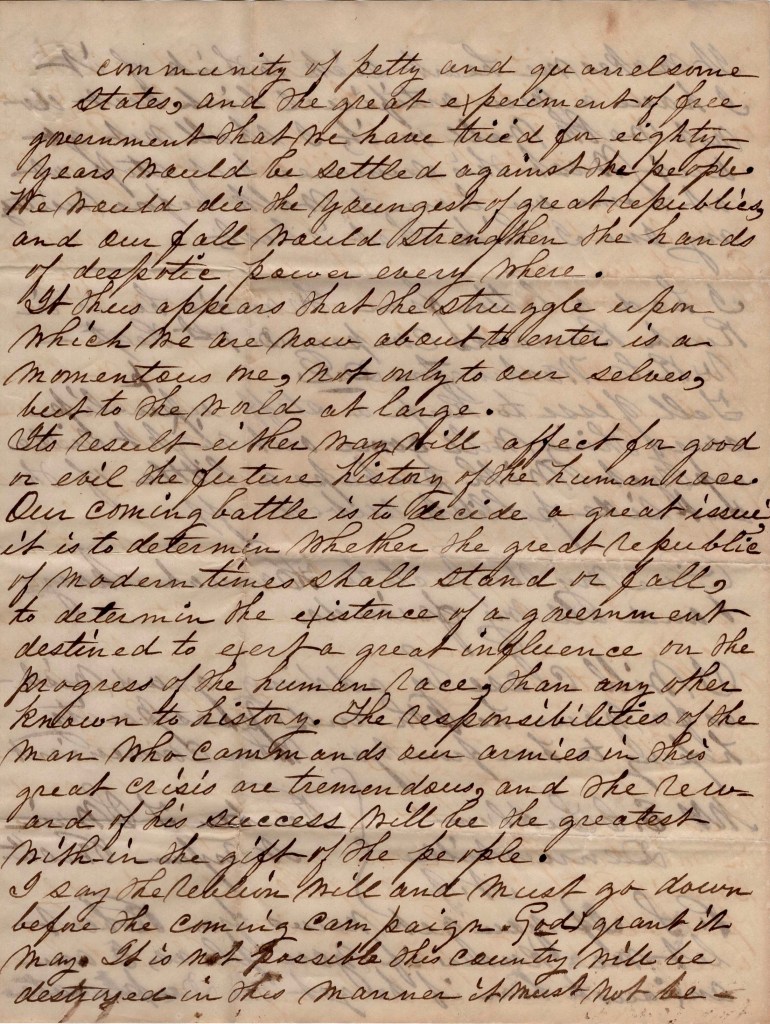

But if Grant should fail, it is hardly possible to say what results may follow. One great disruption would lead to lesser ones. We would be broken up into a community of petty and quarrelsome states, and the great experiment of free government that we have tried for eighty years would be settled against the people. We would die the youngest of great republics, and our fall would strengthen the hands of power everywhere. It thus appears that the struggle upon which we are now about to enter is a momentous one, not only to ourselves, but to the world at large. Its result either way will affect for good or evil the future history of the human race.

“Our coming battle is to decide a great issue. It is to determine whether the great republic of modern times shall stand or fall; to determine the existence of a government destined to exert a great influence on the progress of a human race than any other known to history. The responsibilities of the man who commands our armies in this great crisis are tremendous and the reward of his success will be the greatest within the gift of the people.”

— Reuben T. Swain, 18 April 1864

Our coming battle is to decide a great issue. It is to determine whether the great republic of modern times shall stand or fall; to determine the existence of a government destined to exert a great influence on the progress of a human race than any other known to history. The responsibilities of the man who commands our armies in this great crisis are tremendous and the reward of his success will be the greatest within the gift of the people.

I say the rebellion will and must go down before the coming campaign. God grant it may. It is not possible this country will be destroyed in this manner, It must not be. It makes me heart sick to think of it.

I have a new artificial limb but do not walk well on it. I shall not go out West this summer but stop at home and learn to walk before visiting anyone. I think that is best.

I had a letter from Francis. He is in Rush Barracks, Company D, 1st Regiment, V. R. C., Washington D. C. Tell Jesse to keep a stiff upper lip. Everything will come out right side up yet with perhaps a little of the outside polish rubbed off.

Give my respects to Hannah, Mary and all my friends. I will close by adding good wishes for your health and prosperity, hoping to hear from you when convenient. — Reuben T. Swaim, N. Asylum, Philadelphia

To Mrs. E. C. Ludlum, Dennisville, New Jersey

P. S. If you get news from Robert, let me know if you please. I am anxious to jear if he got the duplicates.

Letter 4

Naval Asylum

Philadelphia

July 15, 1864

Mr. Jesse D. Ludlum, dear sir,

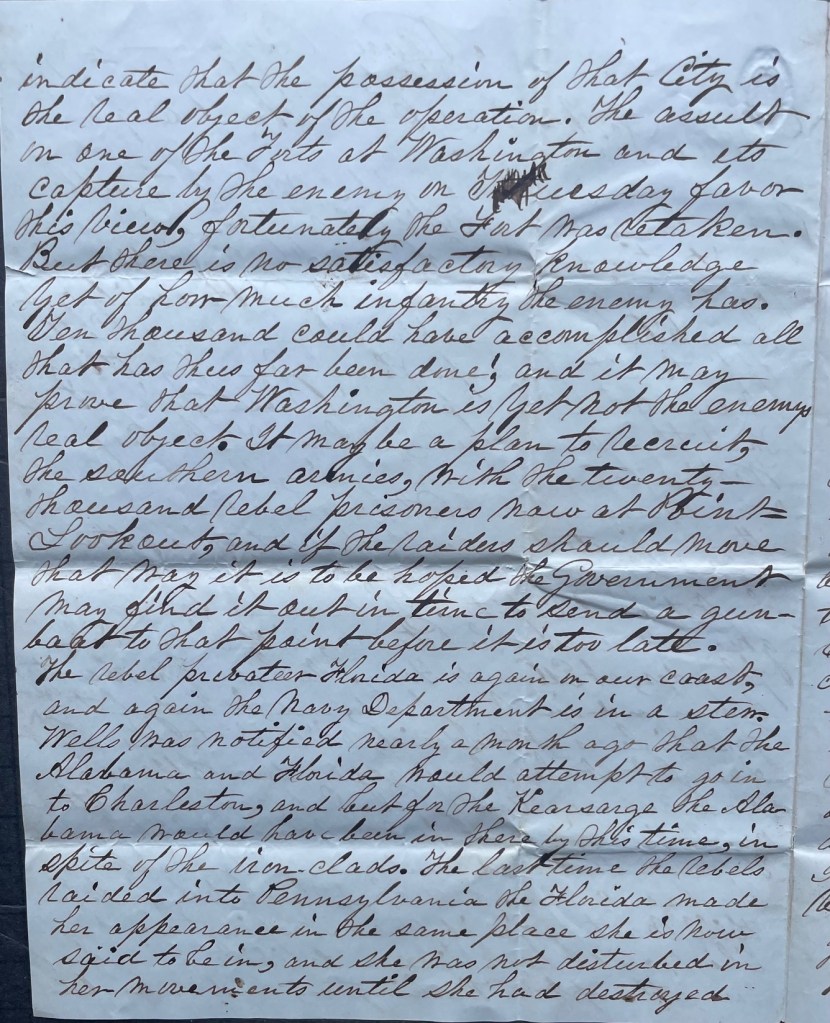

I thought I would trouble you too as well as Emily. I suppose she is quite tired with answering my letters. I certainly feel much obliged to Emily for her kindness, thinking I may have a better opportunity perhaps than you of getting news from the Capitol in those trying times that try mens’ souls. I have the news from Washington regularly again. It seems the rebels were driven from Fort Stevens on Tuesday evening after a spirited assault of our troops after which they seemed to abandon their attempt on the National Capitol. The morning found them gone and crossing the Potomac with their rich plunder at Edward’s Ferry. We have Gen. Hunter’s command in Maryland and the body lately under Gen. Sigel is at Frederick while the troops that fought at the Monocacy under Wallace, now commanded by Gen. Ord, are at Baltimore. It is said that the rebel force which passed through Frederick numbered thirty-eight thousand men and that the Corps of A. P. Hill was to join it near Washington. This would look like a definite plan for an attempt on Washington and would indicate that the possession of that City is the real object of the operation. The assault on one of the forts at Washington and its capture by the enemy on Tuesday favor this view. Fortunately the fort was retaken.

But there is no satisfactory knowledge yet of how much infantry the enemy has. Then thousand could have accomplished all that has thus far been done, and it may prove that Washington is yet not the enemy’s real object. It may be a plan to recruit the southern armies with the twenty thousand rebel prisoners now at Point Lookout and if the raiders should move that way, it is to be hoped the government may find it out in time to send a gunboat to that point before it is too late.

The rebel privateer Florida is again on our coast, and again the Navy Department is in a stew. [Gideon] Wells was notified a month ago that the Alabama and Florida would attempt to go into Charleston and but for the Kearsarge, the Alabama would have been in there by this time in spite of the ironclads. The last time the rebels raided into Pennsylvania, the Florida made her appearance in the same place she is now said to be in, and she was not disturbed in her movements until she had destroyed several of our merchantmen and broken up our fishing fleet for the season. There are several vessels here which can go to sea but they have neither the speed nor batteries fit to cope with those of the Florida.

One respectable vessel has been sent from Portland [Maine]. There are none in Boston, Philadelphia, or New York fit to go and it is more than probable that those in Rear Admiral Lee’s inactive flotilla which are fit for such service have been ordered up to Washington to protect the capitol. It is a crying shame that our commerce should be left thus unprotected and that Rip Van Winkle Wells should have nothing but a lot of washtubs which he is afraid to send out lest they be sunk or captured. Captain [Raphael] Semes is a fine specimen of Southern chivalry. He first surrendered himself and his vessel, and then escaped by turning his hat and coat inside out, swimming to the Deerhound, hiding under a sail, and giving out that he was drowned. Pity he was not drowned—the pitiful wretch.

I have been looking for a letter from Francis very anxiously. I expect he is busy and can get no time to write. The excitement is still great here. Regiment after regiment are leaving daily. I had almost a mind to go too. I am afraid they will be too late to intercept the rebels with their booty, but I think Grant will spare troops to meet them before they get back to Richmond. I do believe that this raid is the best thing that could have happened. It shows [Jeff] Davis that the people can raise a respectable force in a short time when the war is brought too close to their doors North, and there is every prospect that Lincoln will be reelected and Davis knows that the war will go on as long as the Republican Party is in power.

I will close by adding my respects to all and should be happy to hear from you at any time when you can make it convenient. Yours very respectfully, R. T. Swain

Letter 5

[U. S. Naval Asylum, Philadelphia]

[late August 1864]

[Dear Niece]

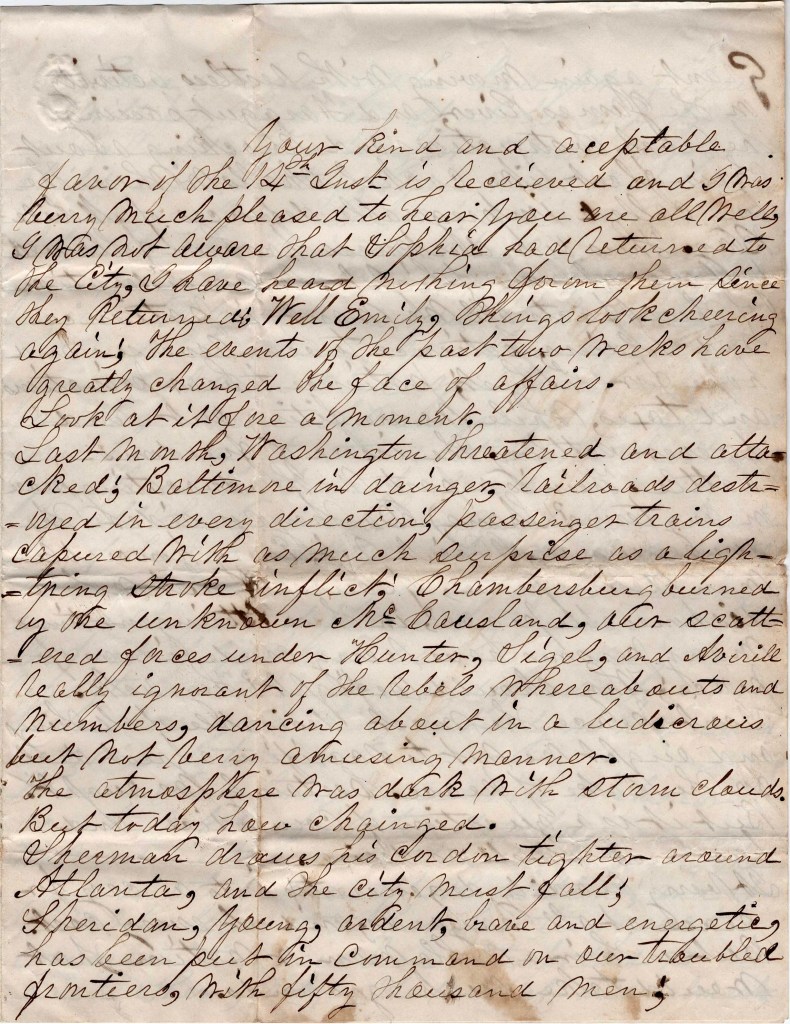

Your kind and acceptable favor of the 14th inst. is received and I was very much pleased to hear you are all well. I was not aware that Sophia had returned to the City. I have heard nothing from them since they returned. Well Emily, things look cheering again. The events of the past two weeks have greatly changed the face of affairs. Look at it for a moment.

Last month Washington was threatened and attacked; Baltimore in danger, railroads destroyed in every direction; passenger trains captured with as much surprise as a lightning stroke inflicts; Chambersburg burned by the unknown McCausland; our scattered forces under Hunter, Sigel and Averill really ignorant of the Rebels whreabouts and numbers, dancing about in a ludicrous but not very amusing manner. The atmosphere was dark with storm clouds.

But today, how changed. Sherman draws in cordon tighter around Atlanta and the city must fall; Sheridan—young, ardent, brave and energetic—has been put in command on our troubled frontiers with fifty thousand men; Grant again moving with restless activity on the James river; and Farragut passing the Rebel obstructions and knocking about their fleet liked cockle shells within the long called impregnable defenses of Mobile Bay. Thus our darkness has been followed by rare gleams of light. In consideration of these facts, all we want is patience and soldiers, patience to bear reverses, and hope for the best; patience to bear privations and taxes while we are fighting it out and forever settling the issue of freedom’s battle.

There is a party [in the] North advocating peace on any terms? (Shame) Do they consider the consequences? I think not. Every honorable man desires peace of course, but not a dishonorable peace/ In these stringent times, many persons have very crude ideas of peace. Why should we fight? they ask. Isn’t peace the most desirable of all things, and ought we not to sacrifice a great deal for the sake of peace? Certainly we ought. But it is a question of cowardice and baseness as well as desire.

It very readily degenerates into a cry for peace at all hazards, and at every cost. But is there a noble man or nation that would take such grounds. Peace can always be bought if you will pay the price. If a robber stops you on the road, if a burglar stands over your child and threatens, you need not break the peace. You have only to give them all they ask and there need be no blows. You may have peace if you will pay the price.

A man leads you by the nose through the streets, you have only to go quietly. A man kicks you, you have only to wait for more. A man grasps your throat, you have only to stand still. He throttles, you have only to drop dead. In all these cases there need be no breaking of the peace, if you cheerfully submit. No man is called upon to favor anarchy under the plea of preserving peace. In fact, if you would have peace, be ready to maintain it and defend it. Peace is a good thing, but only on honorable and manly terms.

When a man buys peace with dishonor, does he not buy it too dearly? We need a better understanding between the good and true men of nothing sections and it must be lamented that these two great communities have been interpreted to each other, not by the wisest and calmest but by the most extreme and hot headed agitators in both sections.

God has given us our guiding law and our moving mind, more deeply perhaps that we are conscious. We feel this twofold gift when we look at the flag of our Union, as we have done at late, and our hearts beat quicker, and our eyes fill with tears of joy and hope as we gaze upon its stars and stripes. Those stars speak to us of laws as fixed as the eternal heavens, and those stripes, as they wave in the breeze, tell us of that mysterious breath which moves through men and nations that they may be born, not of the flesh, but of God.

Give my best respects to Hannah, and Mary, and likewise to all enquiring friends. Hoping you are all well, I close by adding my respects to you, hoping for a continuance of your correspondence, but you must not put yourself to any inconvenience on my account. Very respectfully, your humble servant, — Reuben T. Swain

Letter 6

Naval Asylum, Philadelphia

[Wednesday] October 12th 1864

Dear Niece,

It being dull today after the excitement yesterday in consequence of the election 1 and feeling that I must do something to dispel the general gloom that seems to be gathering around my room, I seat myself to have a few moment’s conversation with you.

Everything passed off quietly yesterday. In fact, we never had a more quiet, peaceable, and good natured political contest in the tendering of every assurance that our old pilot must stand at the helm for four years more. Yesterday was unmarked by any breach of the peace whatever beyond some of the usual wrangling that takes place at street corners between petty politicians who are full of talk, full of certain sort of enthusiasm, full of whiskey, and utterly devoid of discretion. There was little to remind me what an important election was going on except the usual election day street salutations—“Have you voted yet?” [or] “How is it going in your ward?” &c.

Jess must not call me a turncoat when I tell you I voted the Republican ticket yesterday. Heretofore I have been in opposition to the present administration. But now I shall certainly give Abraham my vote. I am forced to choose between two evils and I think by voting for Lincoln, I choose the lesser one. An honest man who may vote for McClellan and Pendleton in the hope that they are thereby vindicating the supremacy of Union and law will find themselves cruelly betrayed when they see the government of their choice truckling at the feet of Jeff Davis and humbly suing for peace which a few months of manly effort might have commanded.

There is but one question before the people on the approaching canvas. Shall we prosecute the war with unabated might until the rebel forces lay down their arms, or shall we—to use the language of the Chicago Convention—make immediate efforts for a cessation of hostilities with view to a convention of all states, &c. Gen. McClellan, the candidate of the Chicago Convention, unfortunately is silent on the only question in regard to which the people cared. That after the election, they will find themselves despised and powerless.

Enough of this kind of talk. I have been going on with politics and foolishness that will not interest you one bit, until I had almost forgotten that I was writing a letter to my niece. Emelie, you must excuse me and I will try and make amends by saying the Rebellion is nearly crushed. Napoleon said Providence was on the side of the heaviest artillery. And so it is with us. God has furnished us with all we need, with His blessing, to crush this Rebellion and then meet any who may adopt her cause. Our most dangerous enemies are those Judases at hoe who are proclaiming their love of country and yet have all their sympathies with the enemy. God is waking His own good pleasure & the day is not far distant when the leaders will abandon their vain attempt & the men will lay down their arms as they did at Fort Morgan & the flag of our Union will wave uninsulted in Richmond and CHarleston, and that sweetest of national anthems—the Star Spangled Banner—shall be sung by North and South everywhere & forever, will send up one universal shout, Hallelujah! The Lord Omnipotent Reigneth. Respects, &c. — Reuben T. Swain

1 On October 11, 1864, Pennsylvania, along with Ohio and Indiana, held important state elections. These elections were considered “bellwether” contests that would indicate public sentiment and potentially predict the outcome of the upcoming presidential election.

Letter 7

Naval Asylum, Philadelphia

Friday afternoon, February 24th 1865

Dear Niece,

Feeling somewhat low-spirited and lonesome today, I take the responsibility upon myself—as Jackson said—of bothering you by writing to you. However, I will go on and say a few words about transpiring events. We had on the 22nd a sort of double holiday commemorating at once the birthday of Washington and the capture of Charleston! The stars and stripes was waving from every public building in the city and to complete the rejoicing came along the news announcing the capture of Fort Anderson, N. C., which added very naturally to the joyous ffeelings which were associated with the day. Fort Anderson is the only obstacle which prevents the capture of Wilmington and with its fall, the fate of the town seems to be assured.

The rapid succession of disasters which have attended the Rebels since Sherman’s march through Georgia are so many sureties of the final success of the Union arms; my opinion is that the loss of Wilmington will necessitate the evacuation of Richmond. I know too little of Sherman’s real designs to predict what he will do. That Hoke will endeavor to reach Florence, S. C., may be presumed, and that Schofield will be close after him rapidly so as to form a union somewhere in North Carolina with Sherman may be as confidently supposed. If Hardee & Hoke manage to join Beauregard, he may consider himself strong enough to face Sherman. And if he can only manage the important matter of feeding them, he may be able to do something in regard to checking Sherman’s march through North Carolina. And the question of ammunition is also important. It is possible that some supplies may have been carried away from Charleston but from the amount left when Gilmore took possession, it is not probable that any large amount could have been taken off by Hardee. What depots there may be in the interior of North Carolina can at present be only conjectured. These are matters which will have an important influence upon the campaign.

At present we can but speculate upon them and await the further development to which the course of events will bring out. At present, let us rejoice that according to all appearance, the Union armies are sweeping up the country clean as they pass on toward their final destination in Virginia.

The Rebels seem to hold on to the idea that if they hold out till the fourth of March next that France will recognize the Confederacy of which delusion our government has reason for complaint against France. The intervention in Mexico was a wrong to us as well as to the Mexicans, and it would not have been attempted had we not had our hands tied by the rebellion at home. These and other grievances that I might name have created an unpleasant feeling in the minds of the American people towards France. Our government is not yet in a condition to demand satisfaction but a day of reckoning must come. The capture of the only two important ports left to the Rebels relieves hundreds of fine war steamers from blockade duty and we could send to France a finer and more formidable naval force than any other power on earth could muster in years. I do not propose that we should go nust now upon any enterprise of this kind. But the knowledge that we might do it, and that we are everyday growing stronger and better able to do it, must make an impression abroad and add weight to any demands we may make upon France for satisfaction for the wrongs she has done.

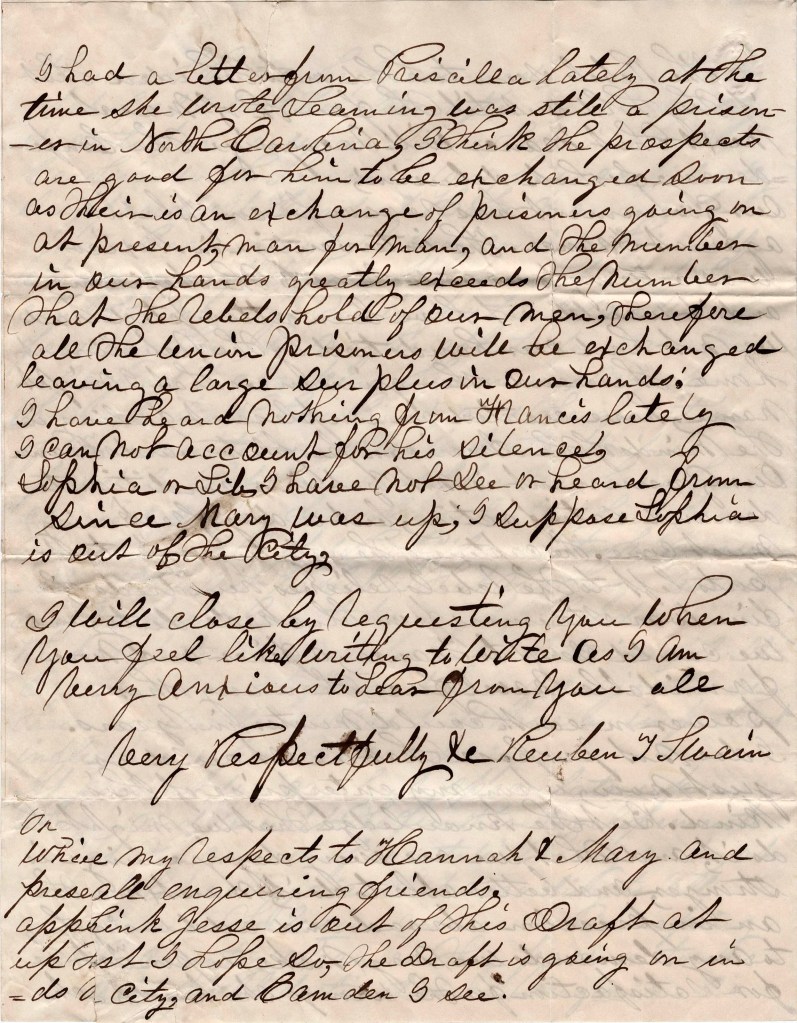

I had a letter from Priscilla lately. At the time she wrote, Leaming was still a prisoner in North Carolina. I think the prospects are good for him to be exchanged soon as there is an exchange of prisoners going on at present, man for man, and the number in our hands greatly exceeds the number that the rebels hold of our men. Therefore, all the Union prosoners will be exchanged leaving a large surplus in our hands. I have heard nothing from Francis lately. I cannot account for his silence. Sophia or Libs I have not seen or heard from since Mary was up. I suppose Sophia ia out of the city.

I will close by requesting you when you feel like writing to write as I am very anxious to hear from you all. Very respectfully, &c. — Reuben T. Swain

My respects to Hannah & Mary and all enquiring friends. It appears Jesse is out of the draft at last. I hope so. The draft is going on in this city and Camden, I see.

Letter 8

U. S. Naval Asylum, Philadelphia

April 1, 1865

Dear Neice,

I think I promised to write to you monthly and not wishing to make an April Fool of you, I seat myself to write to you according to promise. You see by the date it is the first of April and by the first of April, we ought to think of summer. Yet, if we did, we should go far towards proving ourselves April Fools. Even May which is the peculiar darling of poets, is a doubtful beauty, capricious and cold, leading her lovers into miry lanes and meadows, and sending them home with wet feet and colds in their heads. As for you at Dennisville [N. J.], you have no spring. Your climate shares a restless impatience of them permanent and leaps from the zero point straight up to boiling. When one unquestionably warm day burns you a little, you feel that summer has arrived. Then what a bursting out of roses and lilies and what a pulling fourth of muslin duck and drilling.

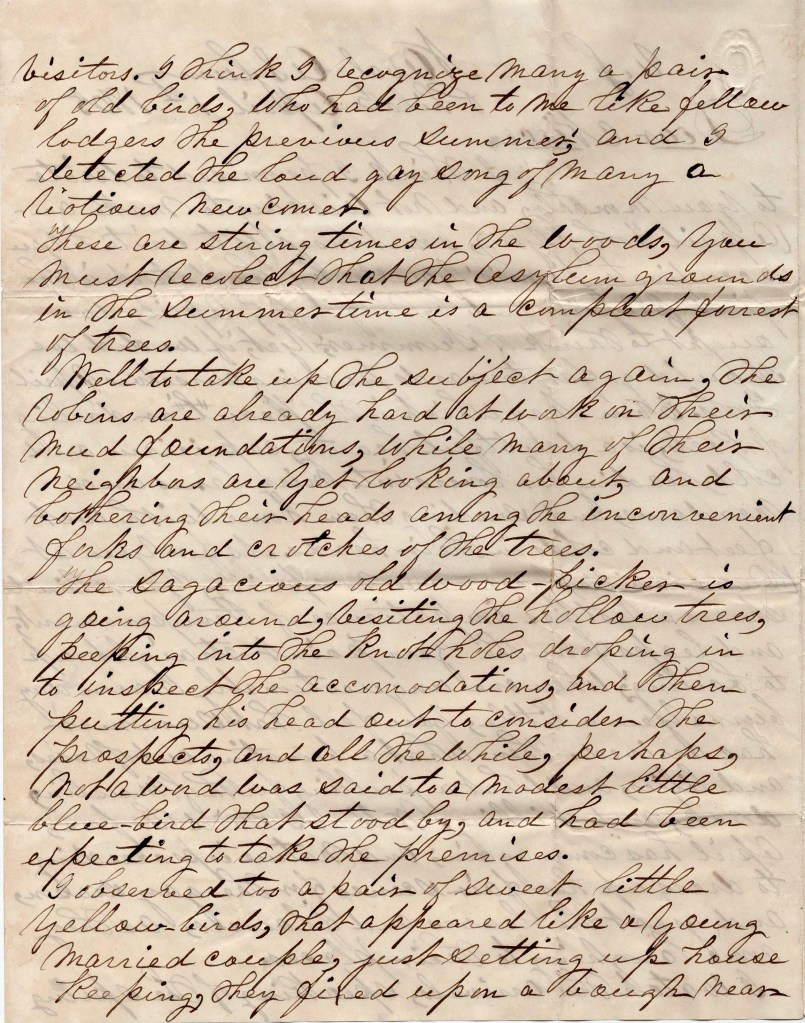

Well, as I said before, April has come again and nature is proceeding to dress up her fair scenes for the day season, and great the leaves and flowers as they come laughing to their places. I watch the arrivals, speaking of the spring visitors. I think I recognize many a pair of old birds who had been to me like fellow lodgers the previous summer, and I detected the loud, gay song of many a riotous new comer. These are stirring times in the woods. You must recollect that the Asylum grounds in the summer time is a complete forest of trees.

Well, to take up the subject again, the robins are already hard at work on their mud foundations, while many of their neighbors are yet looking about, and bothering their heads among the inconvenient forks and crotches of the trees. The sagacious old wood pecker is going around visiting the hollow trees, peeping into the knot holes, dropping in to inspect the accommodations and then putting his head out to consider the prospects and all the while, perhaps, not a word was said to a modest little blue bird that stood by, and had been expecting to take the premises. I observed too a pair of sweet little yellow birds that appeared like a young married couple, just setting up house keeping. They fixed upon a bough near my window and I soon became interested in their little plans and indeed felt quite melancholy when I beheld the troubles they encountered occasionally when for whole days they seemed to be at a stand still. This morning I see they are both at work again and I have not the least doubt that before the end of the month, they little honeymoon cottage will be fairly finished and softly lined.

Well, Emily, I suppose you will say you have had enough of such nonsense about April Fools, and yellow birds, &c. And I think myself I am too apt to run on with my nonsense a little too far, without once thinking of the bother I may give to others. But you must make allowances and come to the conclusion that I have a great deal of leisure time. I think I hear you say, you should find some other way of employing your leisure time.

Well, Emily, it was only yesterday I was comparing the industry of man with that of other creatures in which I could not but observe, that, notwithstanding we are obliged by duty to keep ourselves in constant employ, after the same manner as inferior animals are prompted to it by instinct, we fall very short of them in this particular; reason opens to us a large field of affairs, which other creatures are not capable of Beasts of prey, and I believe, all other kinds in their natural state of being, divide their time between action and rest. They are always at work or asleep. In short, their waking hours are wholly taken up in seeking after their food or in consuming it.

The human species only, to the great reproach of our natures, are filled with complaints, that we are at a loss how to pass away our time; how monstrous are such expressions, among creatures who have the labors of the mind, as well as those of the body, to furnish them with proper employments; who besides the businesses of their proper calling can apply themselves to the duties of religion, to meditation, to the reading of useful books, to the pursuits of knowledge and virtue, and every hour of their lives make themselves wiser or better than they were before.

You must not think that I am criticizing on your time; far from it. Common sense teaches me that anyone who has the care of a family has no spare time. It is myself that I have reference to and I promise hereafter that I will not bother you with such nonsense again.

I have nothing to say about the war further than the prospects are good for the Union. And that it is my earnest prayer that the Union may be preserved. I have not accustomed myself to hang over the precipice of disunion to see whether with my short sight I can fathom the depth of the abyss below. While the Union lasts, we have high, exciting, gratifying prospects spread out before us—for us and our children. Beyond that, I seek not to penetrate the veil. God grant that in my days at least, that curtain may not rise. God grant that my vision never may be opened what lies behind. When my eyes shall be turned to behold for the last time the sun in Heaven, may I not see him shining in the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union. Let their last feeble and lingering glances rather behold the gorgeous Ensign of the Republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, with not a stripe erased or polluted, not a single star obscured, bearing for its motto no such interrogatory as what is all this worth? But everywhere, spread all over, its characters of living light that other sentiment, dear to ever true American heart, “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseperable.”

“It has been said that a special Providence watches over children, drunkards, and the United States. They make so many blunders and live through them, it must be that they are cared for, for they take very little care of themselves.”

— Reuben T. Swain, April 1, 1865

But I am inclined to believe that the Union will last a little longer and that we shall have some good times yet, in time to come. It has been said that a special Providence watches over children, drunkards, and the United States. 1 They make so many blunders and live through them, it must be that they are cared for, for they take very little care of themselves. So I am disposed to trust to Providence, and not to worry.

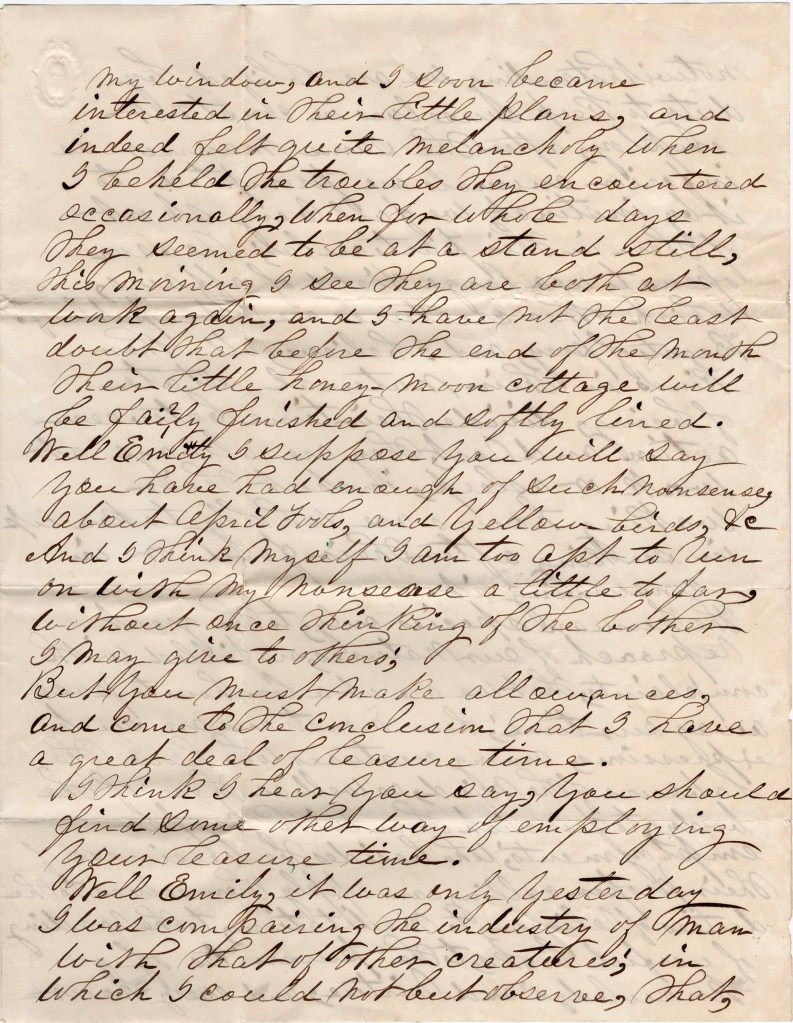

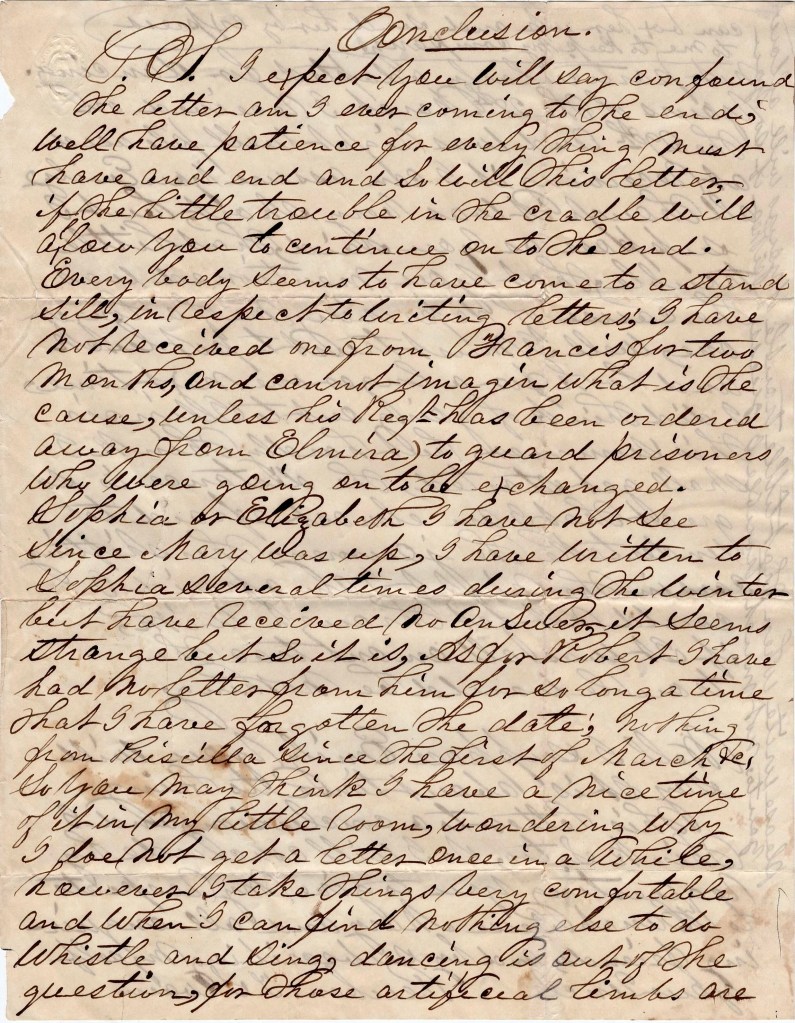

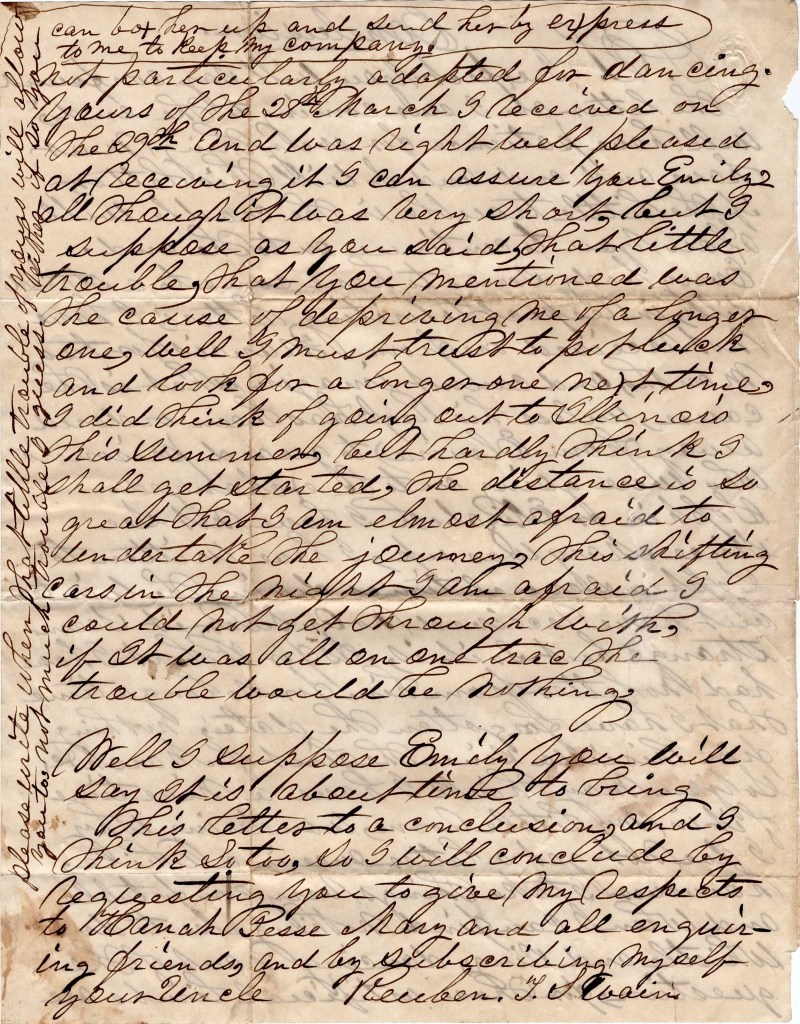

P. S. I expect you will say confound the letter—am I ever coming to the end. Well have patience for everything must have an end and so will this letter, if the little trouble in the cradle will allow you to continue on to the end.

Everybody seems to have come to a standstill in respect to writing letters. I have not received one from Francis for two months, and cannot imagine what is the cause unless his regiment hs been ordered away from Elmira to guard prisoners who were going on to be exchanged. Sophia or Elizabeth I have not seen since Mary was up. I have written to Sophia several times during the winter but have received no answer. It seems strange but so it is. As for Robert, I have had no letter from him for so long a time that I have forgotten the date. Nothing from Priscilla since the first of March, &c. So you may think I have a nice time of it in my little room, wondering why I do not get a letter once in a while. However, I take things very comfortable and when I can find nothing else to do, whistle and sing, Dancing is out if the question for those artificial limbs are not particularly adapted for dancing.

Yours of the 28th March I received on the 29th and was right well pleased at receiving it, I can assure you, Emily, although it was very short. But I suppose, as you said, that little trouble that you mentioned was the cause of depriving me of a longer one. Well I must trust to pot luck and look for a longer one next time. I did think of going out to Illinois this summer, but hardly think I shall get started. The distance is so great that I am almost afraid to undertake the journey. This shifting cars in the night I am afraid I could not get through with. If it was all on one track, the trouble would be nothing.

Well, I suppose Emily you will say it is about time to bring this letter to a conclusion and I think so too. So I will conclude by requesting you to give my respects to Hannah, Jesse, Mary and all enquiring friends, and by subscribing myself your uncle, — Reuben T. Swain

1 This saying appears as early as 1849 in the form “the special providence over the United States and little children”, attributed to Abbé Correa.