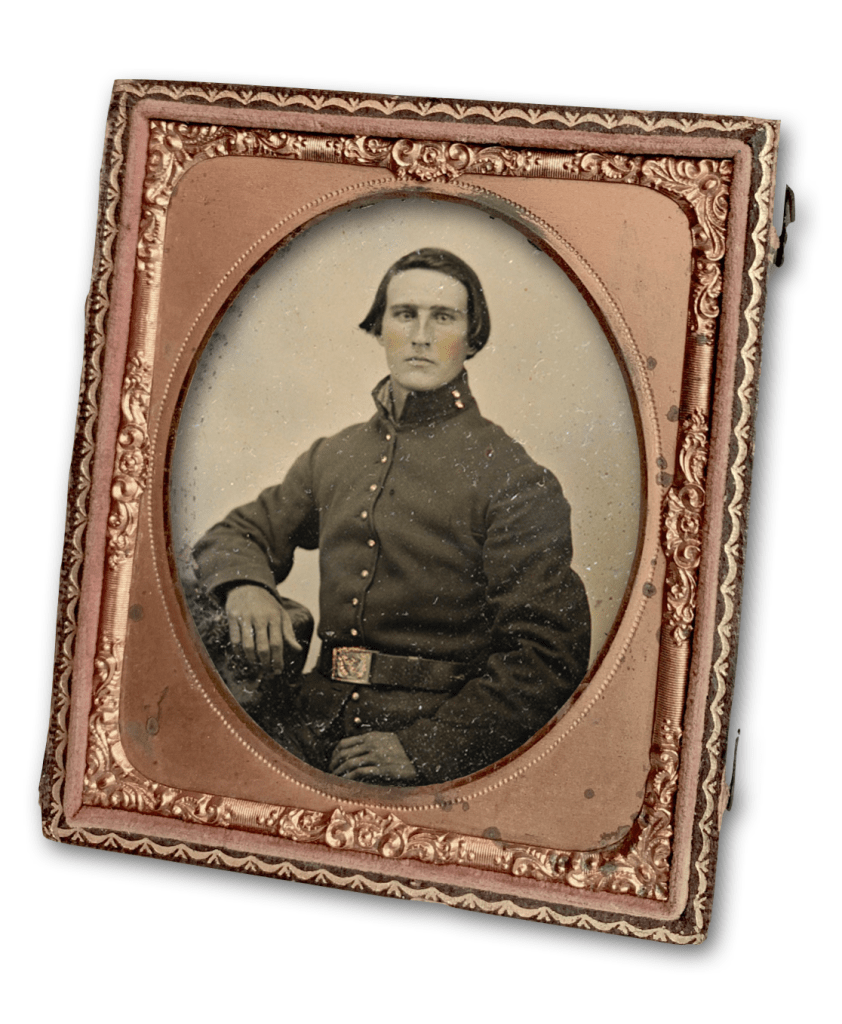

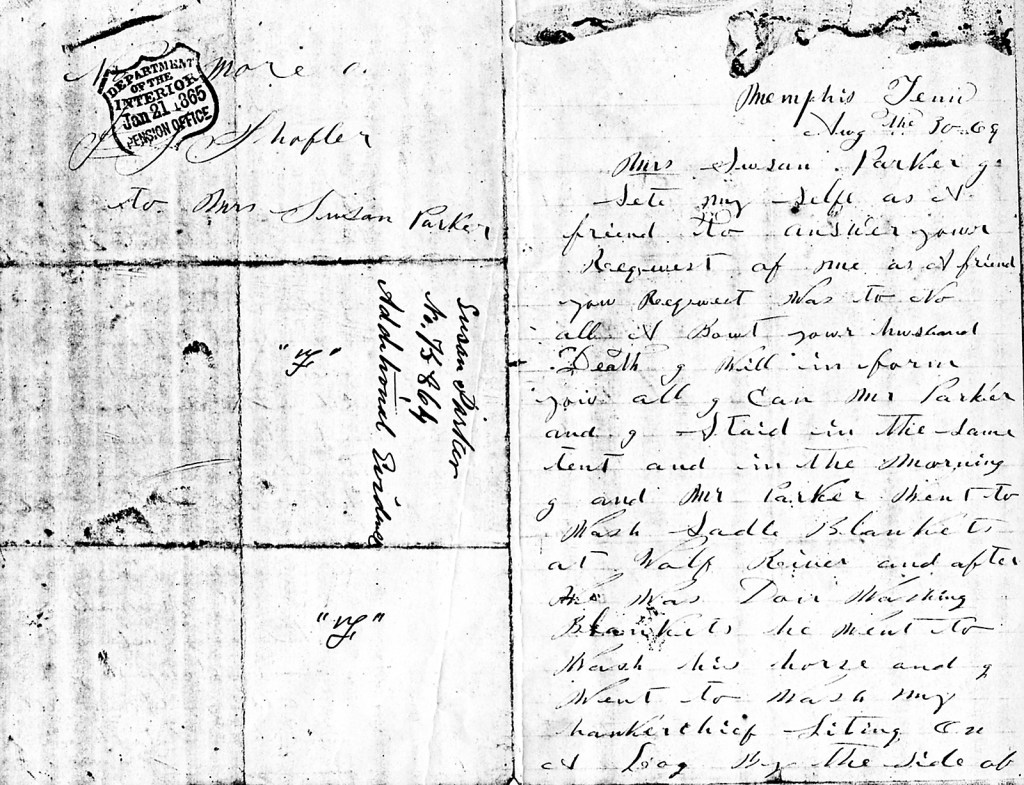

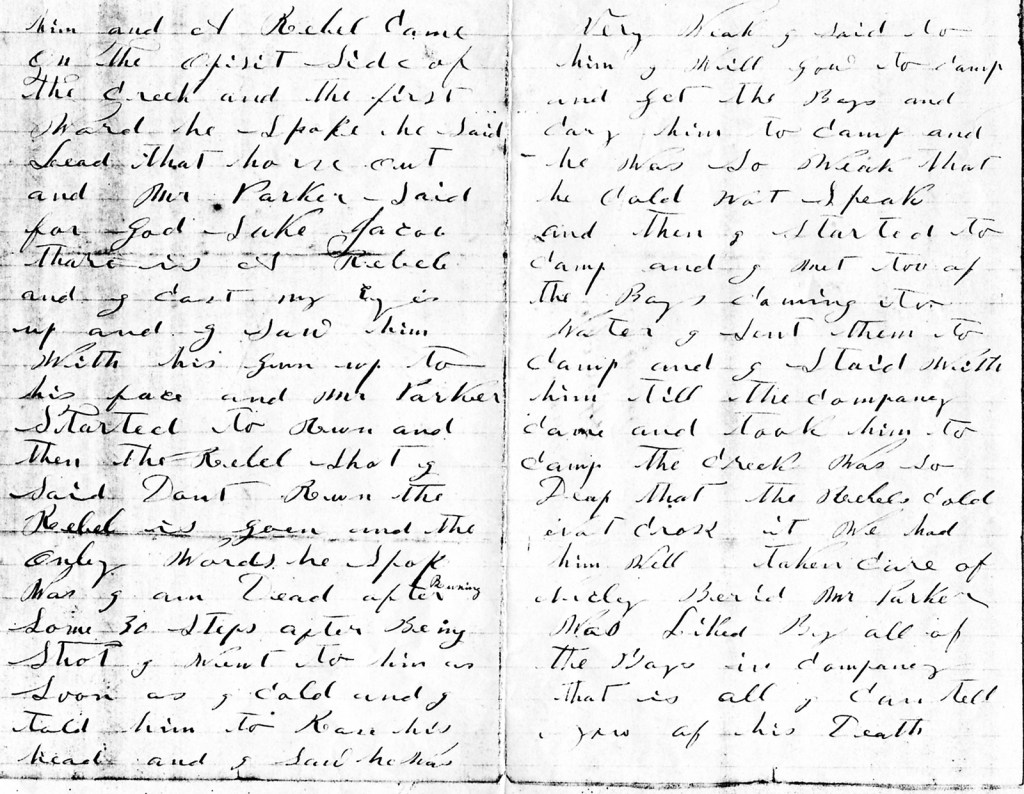

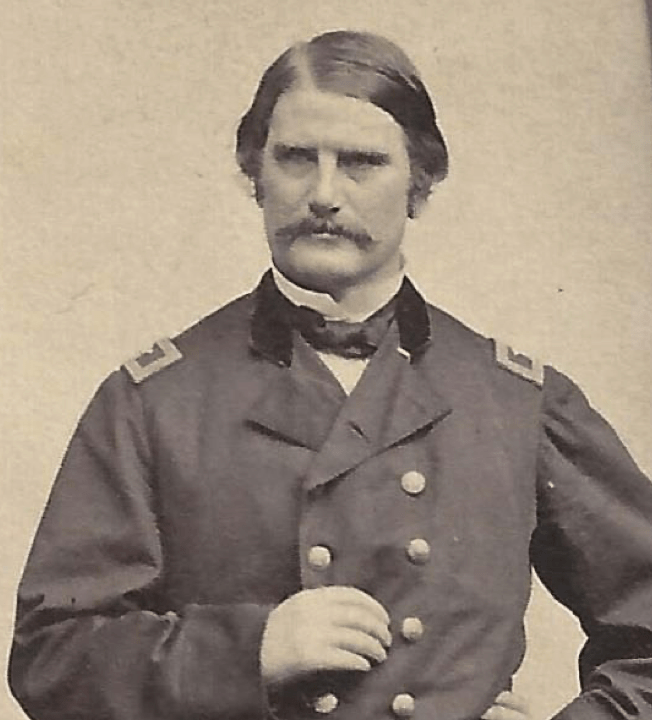

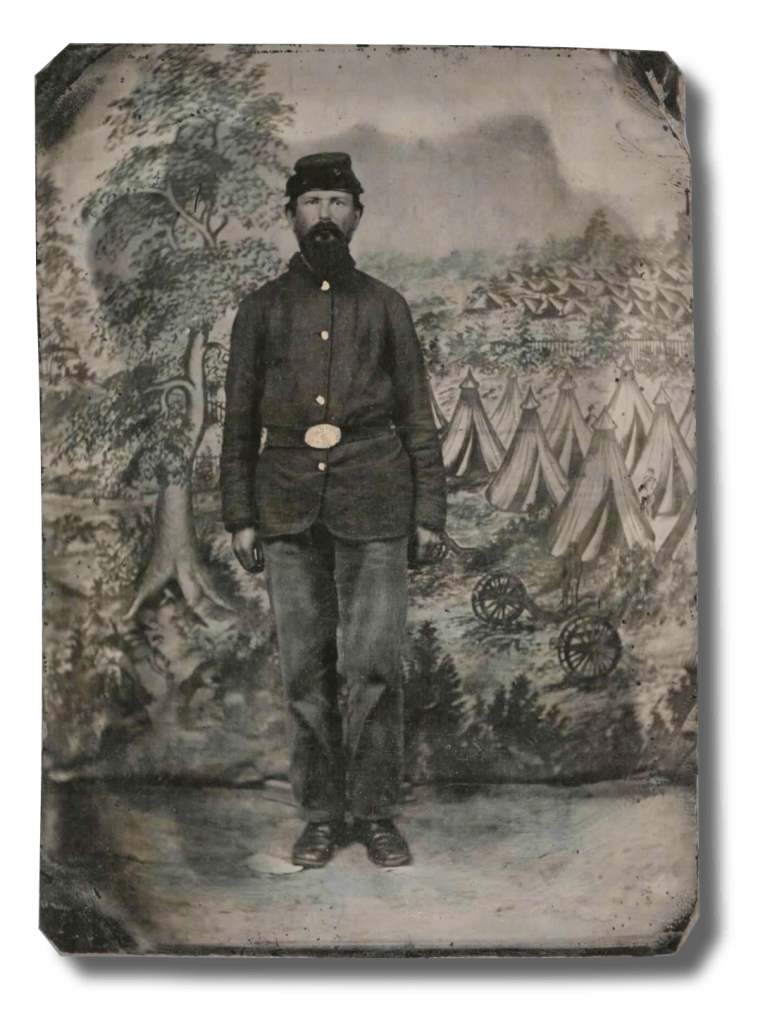

The following letters were written by William F. Carman (1827-1863) of Co. A, 115th Pennsylvania Infantry. According to the pension application, he “died from wounds received at Chancellorsville, Va., May 3, 1863. He left a widow, Emma Carman, and a fifteen year-old daughter, Josephine Carman, of Philadelphia. “Mr. Carman was a shirt cutter. He was a respectable, active, and industrious man, and always took good care of his family.”

I have not been able to find a biographical sketch for William that tells us anything about his parentage but from what I have been able to cobble together, it appears he was born and raised in Baltimore, Maryland. He was, it seems, the oldest child of William Carman (1785-@1855) and Susanna Townsend (1801-1862). The couple were married in the Methodist Church in Baltimore on 23 January 1825. William (the father) was a cripple and made a meagre living cutting hair. Besides William, there were two younger sons—John (“Jack”) F. Carman (b. 1835), and Thomas J. Carman (b. 1837). Thomas, the youngest, was the only son still living at home in 1862 when these letters began, though he enlisted in the US Navy in August 1862 and was assigned to the Steamer United States. Thomas must have been well suited for the Navy for he could apparently drink and fight with the best of the Baltimore rowdies.

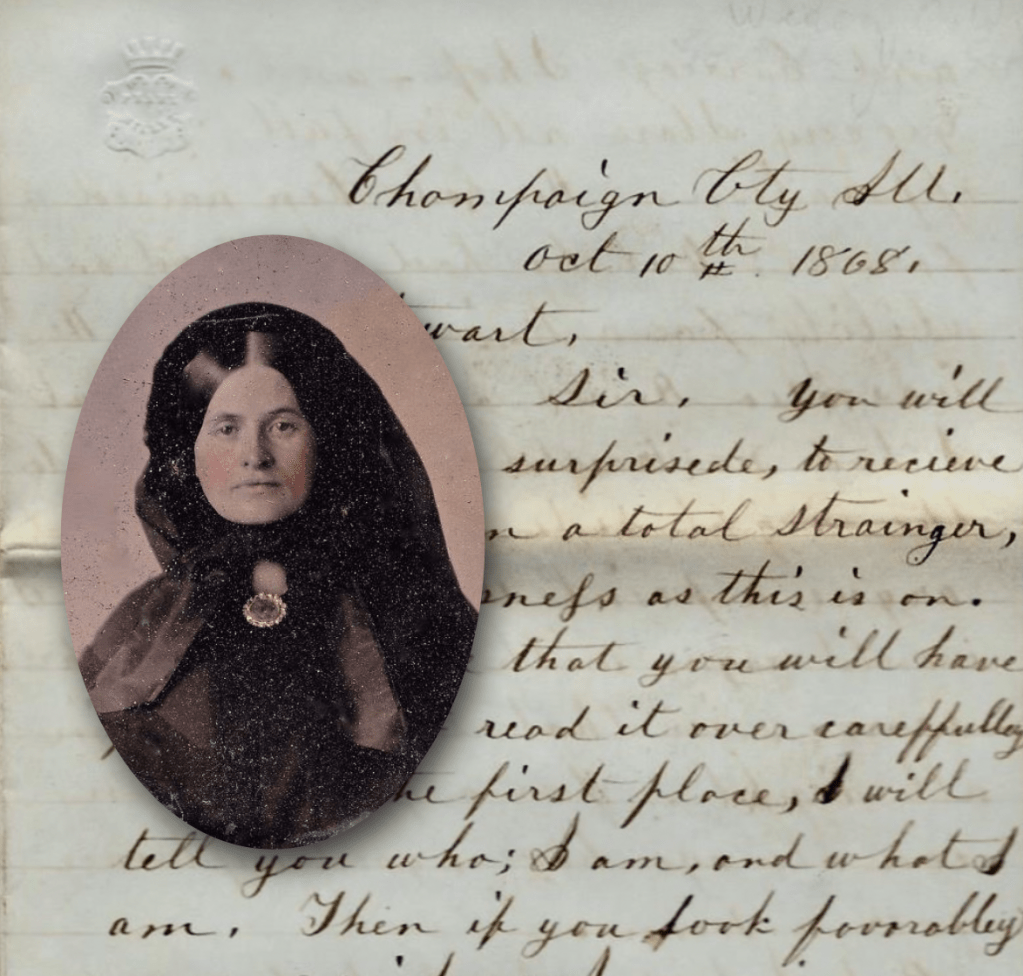

“William F. Carman called his new bride ‘Emma’ when they were married in Baltimore, Maryland in May 1848. Their daughter, Josephine, arrived soon after. By the time the 1860 Federal census was taken, the family had moved from Baltimore to the 3rd Ward of Philadelphia. William worked as a shirt cutter before enlisting on April 2, 1862 to serve a three-year term in the Union army. This left Emma alone to raise their teenage daughter and eventually find a means of support as the Army was slow to pay the soldiers.

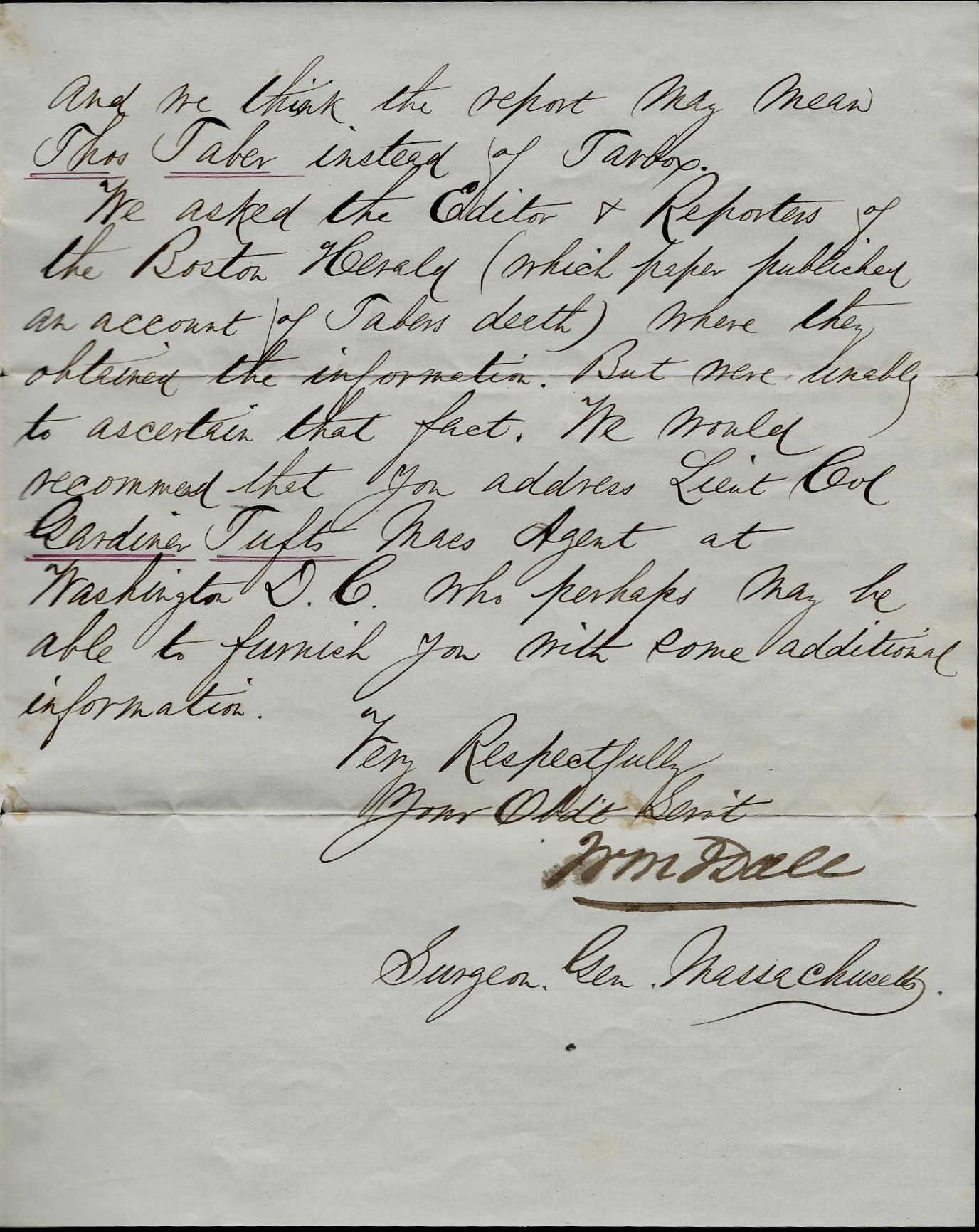

William was devoted to Emma. Emma’s pension file contains thirty-two handwritten letters from William spanning eleven months, the earliest one dated July 1, 1862…The last from William letter is dated June 6, 1863 and appears to be the last one Emma received from him. His death came three days later on June 9.

Emma’s pension file does not provide information on how – or even if – she and Josephine were notified of William’s death, but it does document Emma’s struggles to survive without him. As her mental state spiraled downward, we see her lose grip of William’s letters and his “likeness” in an effort to establish herself as his “legal widow” within the strict bureaucratic government system brokered by the Pension Bureau, only to be overturned in the end by a Special Agent with his ear to a churning neighborhood rumor mill.”

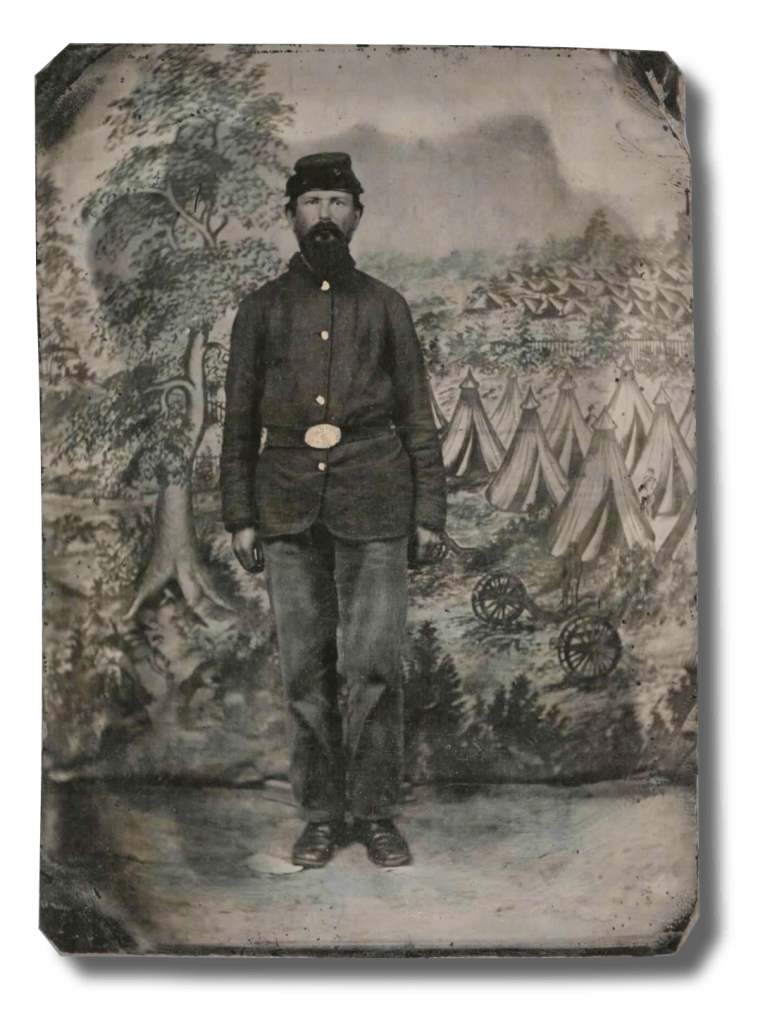

Jackie Budell, an Archives Specialist at the National Archives has meticulously researched Emma’s twenty-year struggle to obtain and maintain a pension for her husband’s service. It is far too long to repeat here so I will merely refer readers to her article entitled, “Why William Carman’s Tintype was in his Widow’s Pension File.”

Suffice it to say that Emma may have had a checkered past and there is evidence that the home William and Emma kept at No. 4 Bath Street in Baltimore before moving to Philadelphia may have been disreputable too. I was able to find an article published in the Baltimore Sun on 15 February 1858 in the “Local Matters” column that was titled, “Another Murderous Affray—Four Men Stabbed and One Shot” described as “one of the most sanguinary affrays without resulting in the death of either of the parties that has occurred in this city for some time.” The article describes the drunken attack and stabbing of William Carmen by his brother Thomas. “The house is occupied by a man named William Carman and his wife, and is notorious as a place for the resort of the dissolute.”

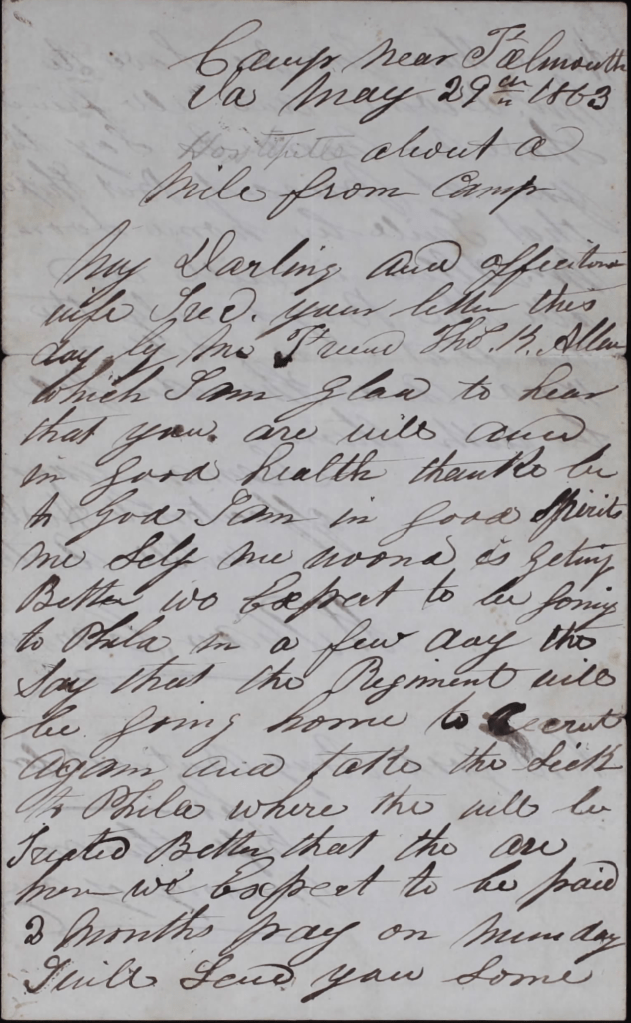

Letter 1

Camp Hamilton

Fortress Monroe, Va.

July 1st 1862

My dear and affectionate wife,

It is with pleasure I write to you to let you know that I am well at present and hope these few lines will find you the same.

We left Harrisburg about a week ago and [have] been traveling ever since. I arrived in Baltimore the same day and seen Tom Carman and George Elliott and Reddy also. Went and seen my mother. She didn’t know me. She took me for Jack and began to cry. But Tom knew me and told her that it was me. He has two fine children. I hadn’t many minutes to stop with them. I was on guard, We left Baltimore the next day in the steamboat for Fortress Monroe. Got there the next day and we have been busy ever since…

We were mustered in for pay today and soon as we get pay, I’ll send you some money. Tom and Mother send their love to you and Josephine. Write soon as you get this and let me know how you are getting along.

Direct your letter to Fort Hamilton, Fortress Monroe, Va.

— William Carman

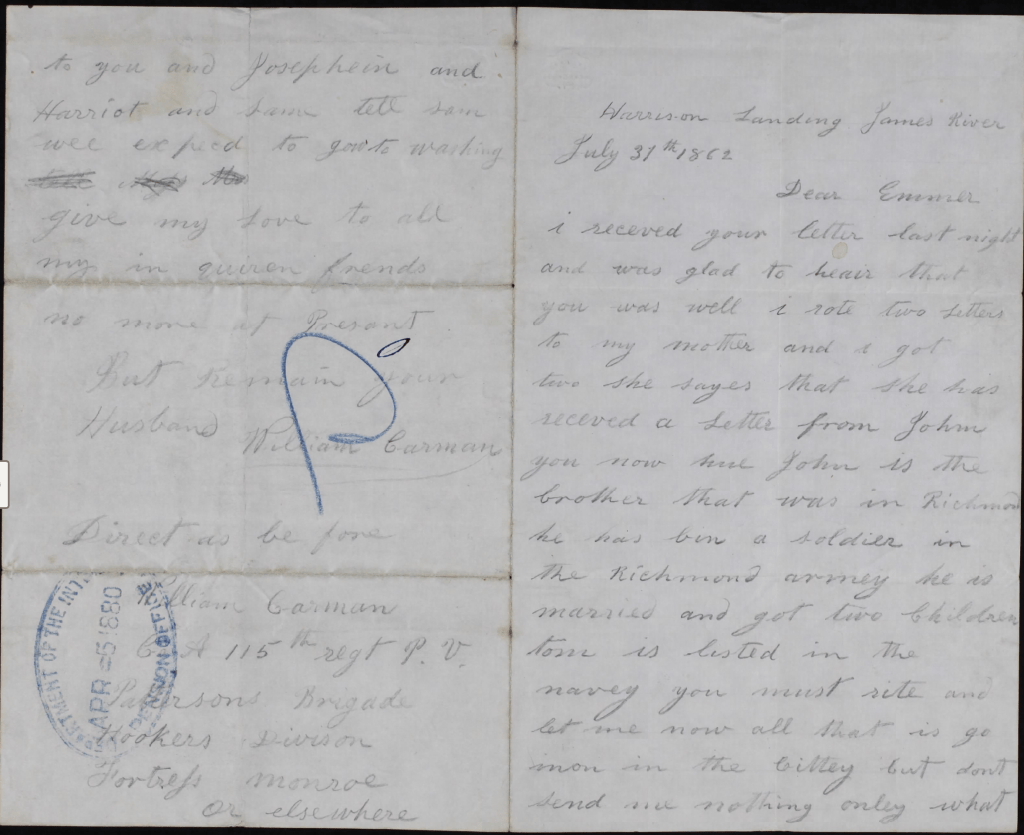

Letter 2

Harrison Landing, James River

July 31, 1862

Dear Emma,

I received your letter last night and was glad to hear that you was well. I wrote two letters to my Mother and I got two. She says that she has received a letter from John. You know her John is the brother that was in Richmond. He has been a soldier in the Richmond army. He is married and got two children. Tom is enlisted in the Navy. You must write and let me know all that is going on in the city but don’t send me nothing—only what I write for.

We are under marching orders and now more boxes are received at the landing. You must tell me in the next letter whether the relief money has stopped or not and also send me a sheet of paper in the letter. I was very glad to find the postage stamps that I wrote for. The five cents I bought some tobacco with. I wanted it very bad.

I hope by the next letter I write to you that I will be able to send you some money and if they pay me all, I can send you a good sum of it.

I send my love to you and Josephine and Harriet and Sam. Tell Sam we expect to go to Washington. Give my love to all my enquiring friends. No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman

Direct as before. William Carman, Co. A, 115th Regt. P. V., Patterson’s Brigade, Hooker’s Division, Fortress Monroe, or elsewhere.

Letter 3

Harrison’s Landing

James River

August 8th 1862

Dear wife,

Your kind letter come to hand last night. Was glad to hear that you was well. I also received one letter from my Mother. She says that she ain’t very well at present. Tom thinks he will come to Fortress Monroe. If he doesm he will have something to do.

On last Monday evening we had orders to march about half past four o’clock. We marched nearly all that night till we came to a place called Malvern Hill. Here we sat down and rested for an hour, then got ready for to go into the field for a fight. Our men marched up bravely. The fight lasted one hour. The artillery and gunboats done all the work. Our men were only drawn up in line. The shot and shell fell very thick for awhile [and when] the Rebels could not stand it any longer, they retreated. We took two hundred and fifty prisoners, five hundred head of cattle, killed and wounded about fifty. There was some of our men killed and wounded—about twenty-five. We stayed there all that day and all that night nearly when we took up the line of march for camp. We arrived next morning. There was nobody hurt in our regiment.

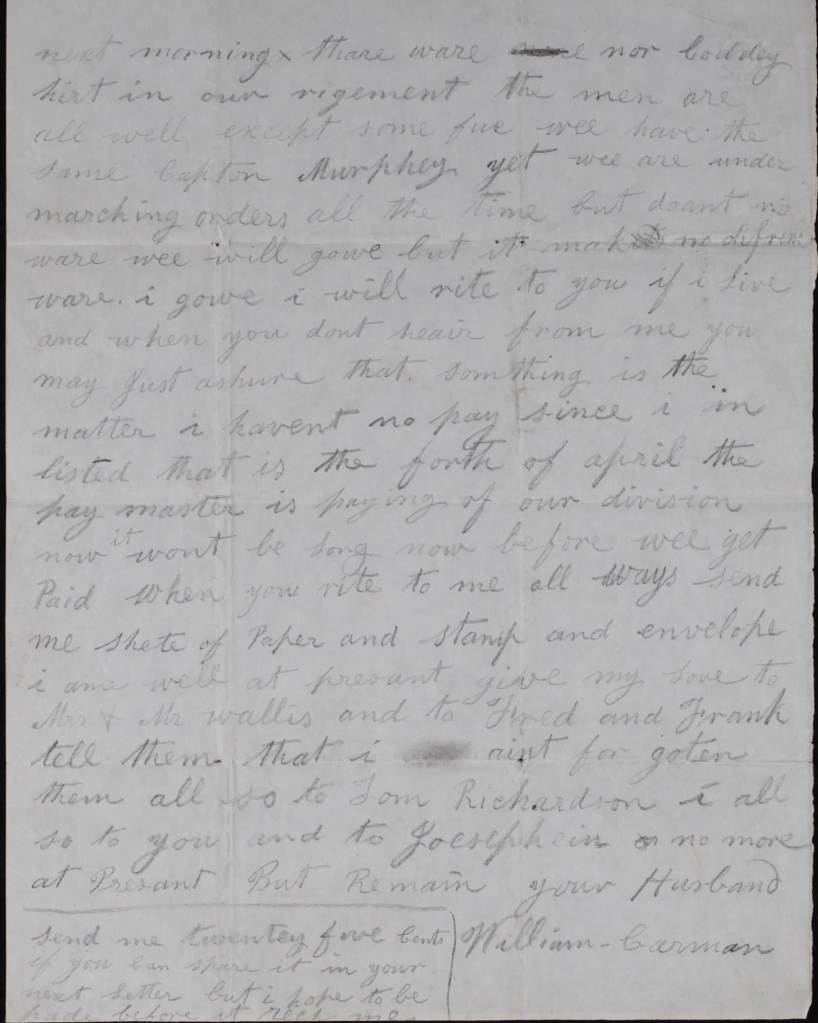

The men are all well except some few. We have the same Captain [Patrick O’]Murphy 1 yet. We are under marching orders all the time but don’t know where we will go but it makes no difference where I go. I will write to you if I live and when you don’t hear from me, you may just assure [yourself that something is the matter. I haven’t [received] no pay since I enlisted—that is the 4th of April. The pay master is paying off our division now. It won’t be long now before we get paid. When you write to me, always send me a sheet of paper and stamp and envelope.

I am well at present. Give my love to Mrs. and Mr. Wallis and to Fred and Frank. Tell them that I ain’t forgotten them. Also to Tom Richardson and also to you and to Josephine. No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman

Send me twenty-five cents if you can spare it in your next letter but I hope to be paid before it reaches me.

1 Patrick O’Murphy served as the captain of Co. A, 115th Pennsylvania Infantry from the time the regiment was mustered into service on 21 April 1862 until he was discharged on 25 June 1863. From William’s letters it does not appear that O’Murphy sent much time in the field with his company.

Letter 4

Alexandria, Virginia

Sunday, September 14th 1862

My dear and affectionate wife, Emma Carmans,

Your kind letter came to hand last night and I was glad to hear that you was well. We are still encamped near Alexandria but there are nothing new going on here at present. We don’t know how long we will stay here. I also received a letter from my Mother. She says things is very dull in Baltimore. She got a letter from Tom. He is on board the United States Steamer now laying in Norfolk, Va.

Dear Emma, I am very much obliged to you for sending me the silk and needles, Also the stamps and paper for I hadn’t none for to write on. Give my love to Josephine. Tell her that in 48 hours after the pay master comes, she will receive it. We are expecting him every day now.

Dear Emma, I send my best love to you. Also give my best respects to Mr. and Mrs. Wallis and to Fred and Frank. Tell them that I am well but I feel very sassy at present. No more at present but remain your affectionate husband, — William Carman

Please send me three envelopes as I haven’t got none. I have paper. Direct your letter as before.

Letter 5

Camp Hooker near Alexandria, Va.

September 23rd 1862

My Dear Wife,

Your letter I received this day after coming into camp after a week’s absence and was glad to hear that you was well at present but I was very sorry that I could not go to Philadelphia on account of having no money.

Dear wife, you speak about Fanny the dog. I suppose he thought he would see me for I ought to have been there at the same time because I had a furlough for one week and couldn’t get no further than Washington. There I had to stop on account of having no money. There I remained a week till it was time for me to go to camp.

The first day I got in Washington I come across my old friend, Robert Rainey, and I stopped at his house the whole time. He sends his best respects to you. When I was in Washington, I went three days to the General Paymaster Office for to see our paymaster and they told me he was paying our regiment but he ain’t come to camp yet. But I hope he will be here this week for I am getting tired of waiting for him.

I am very glad you seen Capt. O’Murphy. I suppose he told you all about the [Second] Bull Run fight. Give my respects to Fred and Frank. Tell them that I am well. Also to Mrs. and Mr. Wallis [Wallace?] and to Mrs. Laws. I don’t hear anything about the regiment that James is in at all.

Tell Josephine that I hope to send her present next week if the pay master comes.

Letter 6

Camp Hooker near Alexandria, Va.

September 24, 1862

Dear Wife,

After writing my letter, I received one from my sister bringing me the melancholy news of my Mother’s death. She died on Sunday, half past three o’clock which makes me feel very sorry. I was the only one she wished to see. My sister got a letter from me just in time to read it to her before she died for she was looking every minute to hear from me before she died. There wasn’t one of the boys at home to see her.

I send my best love to you and to Josephine. Also to Mr. and Mrs. Wallace. Also to all my inquiring friends. Give my respects to Harriet Laws and Ginny and Sissy. Don’t forget to give my respects to Fred and Frank. Tell them that they must write.

Dear Emma, please to send me a few postage stamps as soon as you can for I have none at present. I think we will be paid this week or the first of next. No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman

Direct your letter to me, William Carman, Co. A, 115th Regt. P. V., Patterson’s Brigade, Washington D. C. , or elsewhere.

Letter 7

Camp Hooker near Alexandria, Va.

September 29, 1862

My Dear Wife,

Your kind letter dated 26th inst. came to hand on Saturday night and I was glad to hear that you was well but I feel very sorry to think that the people impose on you since I left. But dear Emma, try and keep quiet till I get paid and if I get all that is coming to me, I will send you the biggest half of it and then you be careful how you spend it because we don’t get paid when we want to.

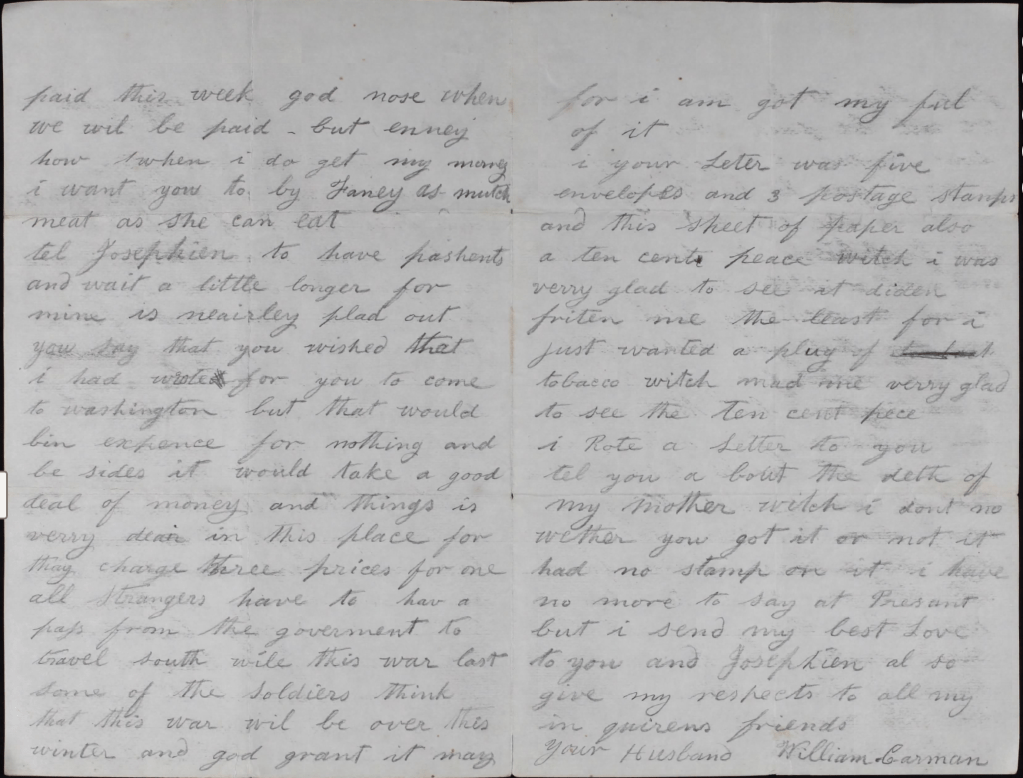

Dear Emma, when I was in Washington, I didn’t enjoy myself one bit although I had all I wanted to eat and drink. But that didn’t satisfy me for I wanted to get home to see you and Josephine. If we don’t get paid this week, God knows when we will be paid. But anyhow, when I do get my money, I want you to buy Fanny as much meat as as she can eat.

Tell Josephine to have patience and wait a little longer for mine in nearly played out. You say that you wished that I had wrote for you to come to Washington but that would have been an expense for nothing. And besides, it would take a good deal of money and things is very dear in this place for they charge three prices for one. All strangers have to have a pass from the government to travel south while this war lasts. Some of the soldiers think that this war will be over this winter and God grant it may for I am got my full of it.

In your letter was five envelopes and three postage stamps and this sheet of paper. Also a ten-cent piece which I was very glad to see. It didn’t frighten me the least for I just wanted a plug of tobacco which made me very glad to see the ten-cent piece.

I wrote a letter to you to tell about the death of my mother which I don’t know whether you got it or not. It had no stamp on it. I have no more to say at present but I send my best love to you and Josephine. Also give my respetcs to all my inquiring friends.

Your husband, — William Carman

Letter 8

Camp Hooker near Alexandria, Va.

October 4th 1862

My Dear Wife,

The pay master has come and paid us and the men were all glad to see him but they didn’t get as much as they expected for they took some money to pay for the clothing they had drawn.

Dear Emma, I enclose you twenty-five dollars which five of it you must give to Josephine for the present I promised to her. I intended to send Josephine more but couldn’t. You can tell her [it was] on account of helping to pay the funeral expenses of my mother.

Dear wife, you must answer this letter as soon as you get it for I have a little more money to send you. I didn’t like to send it all in one letter for fear that it might not come to you. I want you to send me twenty-five cents worth of postage stamps and nothing else.

I had to send twenty dollars to Baltimore which leaves me five after I send you some more. We will get paid every two months now so the paymaster says and that won’t be long a coming now and I can send you more money. Don’t forget Fanny. Be sure to get some meat for her. I send my best love to you and Josephine. Give my best respects to Fred and Frank and to Mr. and Mrs. Wallace. You can tell them that I am well and if I live to come home, I mean to have a good time of it. No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman.

Direct to me: Co. A, 115 Regiment P. V., Grover’s Division, Patterson Brigade, Washington D. C. or elsewhere.

Get your coal and wood for the winter and be careful that nobody cheats you in making change.

Letter 9

Camp near Alexandria, Va.

October 9th 1862

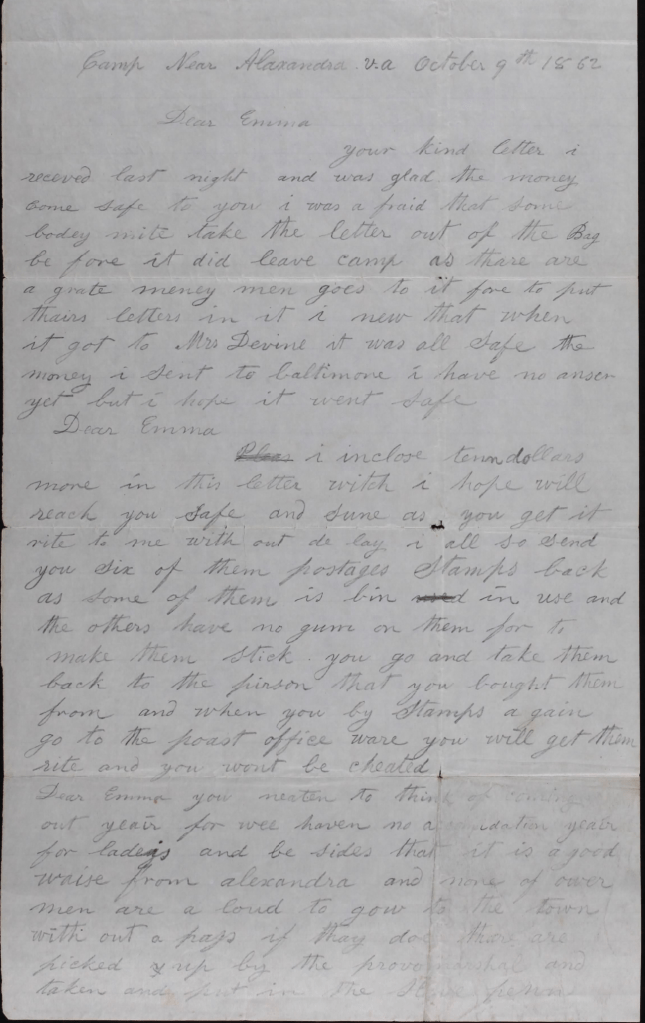

Dear Emma,

Your kind letter I received last night and was glad the money came safe to you. I was afraid that somebody might take the letter out of the bag before it did leave camp as there are a great many men goes to it for to put their letters in it. I knew that when it got to Mrs. Devine, it was all safe. The money I sent to Baltimore I have no answer yet but I hope it went safe.

Dear Emma, I enclose ten dollars more in this letter which I hope will reach you safe and soon as you get it, write to me without delay. I also send you six of them postage stamps back as some of them has been in use and the others have no gum on them for to make them stick. You go and take them back to the person that you bought them from and when you buy stamps again, go to the post office where you will get them right and you won’t be cheated.

Dear Emma, you needn’t to think of coming out here for we haven’t no accommodations here for ladies. And besides that, it is a good ways from Alexandria and none of our men are allowed to go to the town without a pass. If they do, they are picked up by the Provost Marshal and taken and put in the slave pen where they stay for two weeks before they get out.

We are under marching orders and we don’t know how long we will be here but I hope they will countermand them for I don’t care about going to fight anymore this winter. I would like to stay here or somewhere about the neighborhood this winter.

I am very glad to hear that Sam Laws is well for he must have seen a hard time of it.

Now Emma, don’t you go and spend all your money in furniture that ain’t one bit of use to you. It will be six or seven weeks before I get anymore but soon as I get paid again I will send you some more. Send Fred and Frank my best respects. Also give my respects to Mr. and Mrs. Wallace. You can tell them I am well, I also send my love to you and Josephine. And tell Josephine I was very sorry I couldn’t send her more of a present that I did. I have no more to say but remain your husband, — William Carman

Direct your letter as before.

Letter 10

Camp Kearny, Va.

October 15, 1862

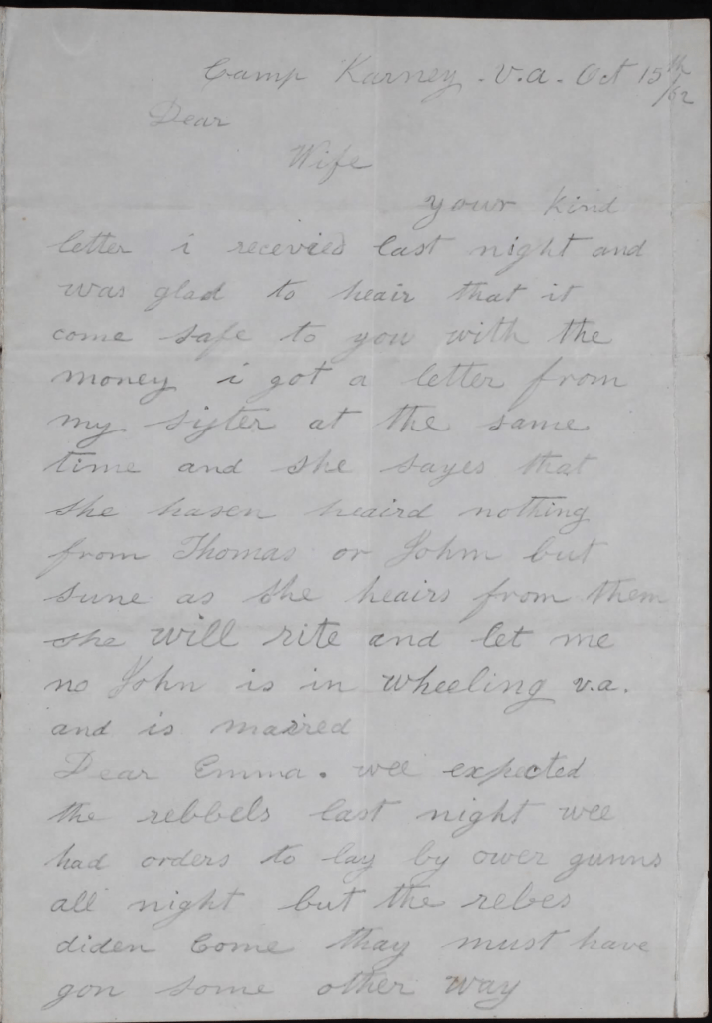

Dear Wife,

Your kind letter I received last night and was glad to hear that it came safe to you with the money. I got a letter from my sister at the same time and she says that she hasn’t heard nothing from Thomas or John but soon as she hears from them she will write and let me know. John is in Wheeling, Virginia, and is married.

Dear Emma, we expected the rebels last night. We had orders to lay by our guns all night but the rebs didn’t come. They must have gone some other way.

Dear Emma, I am very much obliged to you for sending me the postage stamps and envelopes and I am very sorry that I haven’t nothing for to send you in return but as soon as I get paid, I will send you some more money which I hope won’t be very long. I don’t want you to send me anything for I don’t want nothing at present, but I feel very thankful for what you have already sent me. I am well and I hope these few lines will find you the same. You must giver my kind respects to Mr. and Mrs. Wallace and to Fred and Frank if you see him anymore. And you tell Frank that he won’t find sailor life like home.

Dear Emma, I send my best love to you and Josephine. Is Josephine doing anything now or is she living home with you. Reason I ask the question, I seen her name in one of the Baltimore papers where she was to dance. I haven’t no more to say at present but give my respects to all my enquiring friends.

Very respectfully your husband, — William Carman

Letter 11

Camp Van Lear, Virginia

October 29th 1862

My dear Emma,

Your kind letter come to hand and I was glad to hear that you and Josephine was well. I am very much obliged to you for your kindness for sending me the postage stamps and paper. I have enough to last me some time and I don’t want nothing else now at present.

You say that you would like to come down here but you take a fool’s advice and stay home for this is no place for ladies for there ain’t nothing but men and boys down here and some of them ain’t got no manners about them whatever. Besides that, it would be a great deal of trouble and expense for nothing. You would have to get a pass just as a negro before you could go anywhere and there ain’t no accommodation whatever for there ain’t no place that you could stay at night at and it is very disagreeable weather just about this time of the year for the roads are knee deep with mud. We have had a very rainy week of it.

Dear Emma, I can only send you my likeness but if there are any way of getting a furlough or [my] getting to Philadelphia this winter, I will try to come. You needn’t to take this likeness around for a show nor laugh at it for the man that took it [did] the best he could out here.

Give my respects to Mr. and Mrs. Wallace and to Fred. Also to Cody Carlson when you see him. I would like very much to see Fred and Cody. I haven’t heard nothing from Baltimore since I wrote you last. Don’t neglect Fanny.

We will be mustered in for pay in a week’s time. I send my love to you and Josephine and very much obliged to Josephine for her kind offer but I shan’t write for nothing at present. Write soon as you receive this. No more but remain your husband, — William Carman

Direct your letter as before. Let me know how Sam Laws is when you hear.

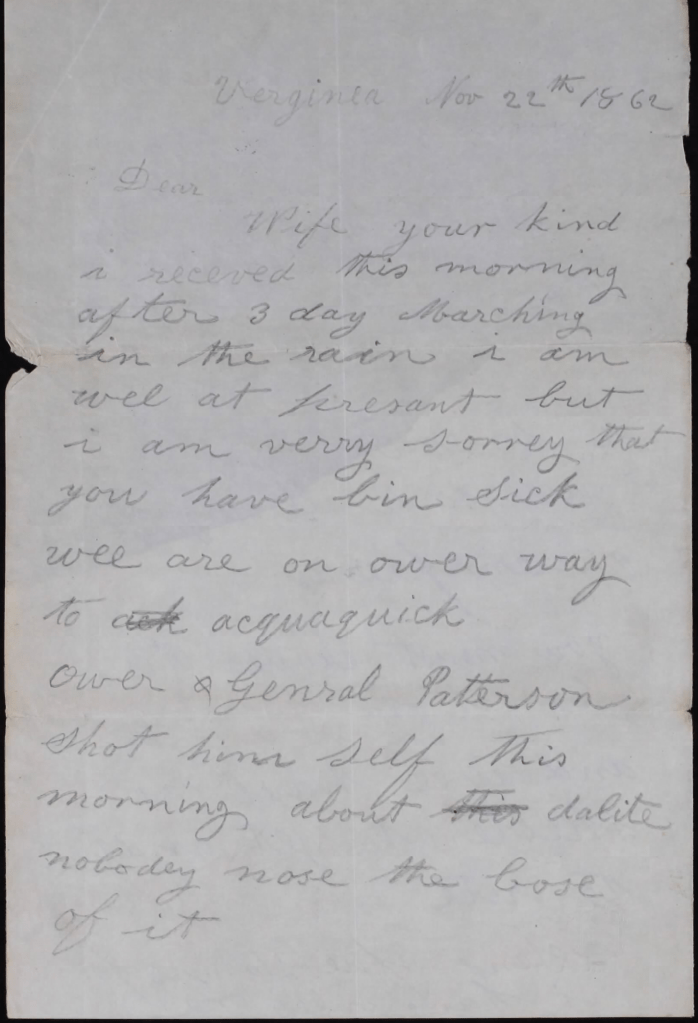

Letter 12

Virginia

November 22 [should be November 2], 1862

Dear wife,

Your kind [letter] I received this morning after three days marching in the rain. I am well at present but I am very sorry that you have been sick.

We are on our way to Aquia Creek. Our General [Frank] Patterson shot himself this morning about daylight. Nobody knows the cause of it. 1

No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman

I send my love to you and all my enquiring friends. You must excuse this for it is raining and we have no shelter to get under to write. Send a few stamps for I have only one.

1 Patterson was at Catlett’s Station when he withdrew his brigade upon hearing unconfirmed reports of a Confederate troop presence nearby. Sickles accused him of retreating without orders and called for a military board of inquiry to court-martial him. However, on November 2, Patterson was found dead in his tent of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Initially it was not clear whether his death was accidental or a suicide. But an article in The Baltimore Sun from 29 November 1862 cites an eyewitness, Capt. Vreeland of the 8th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry who was with him in his tent at the time. Vreeland states that Patterson “committed the act while under a temporary insanity … so suddenly was the rash act committed that (I) could not stay his hand.”

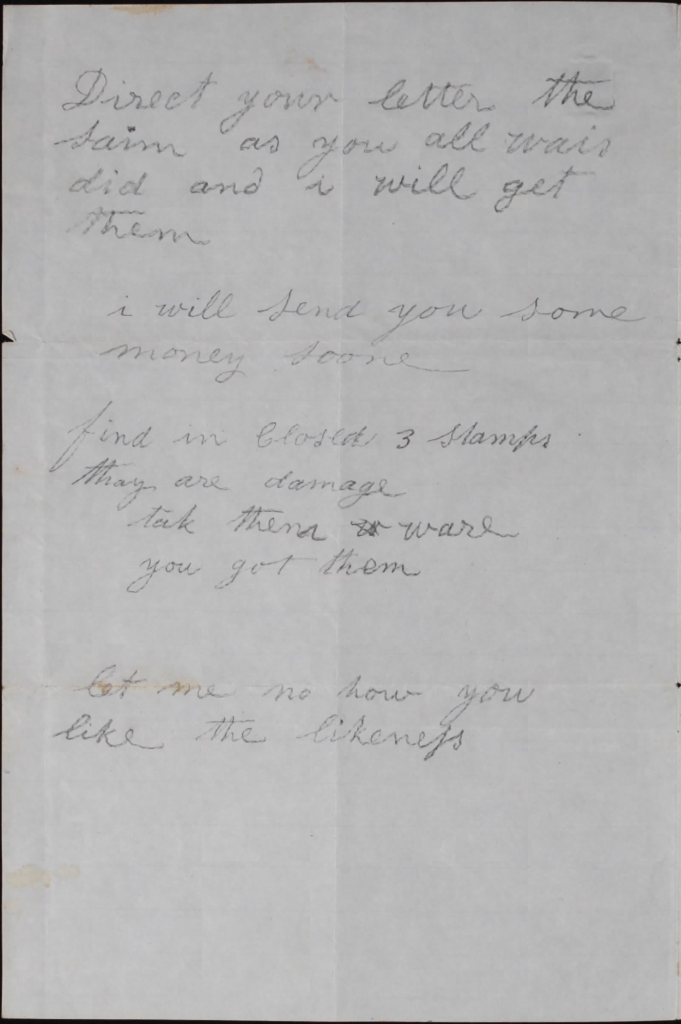

Letter 13

Bristoe Station, Virginia

November 5, 1862

Dear Emma,

What is the matter you don’t write? I would like to hear from you.

We expect to have a battle soon. The whole army is moving towards Richmond. I am well at present and we will get paid in a few days. The weather is very cold and it is snowing very fast at present.

I send my love to you and Josephine and to Mr. and Mrs. Wallace. Also to Fred and Cody Carlson. No more at present. Your husband, — William Carman

Direct your letter the same as you always did and I will get them. I will send you some money soon. Find enclosed 3 stamps. They are damaged. Take them where you got them. Let me know how you like the likeness.

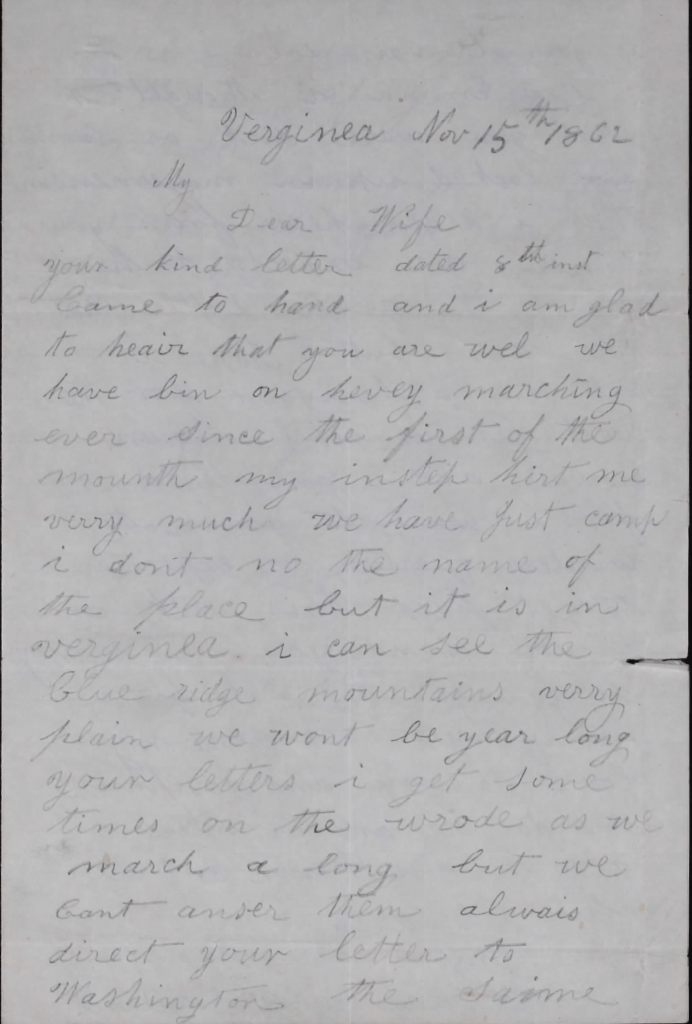

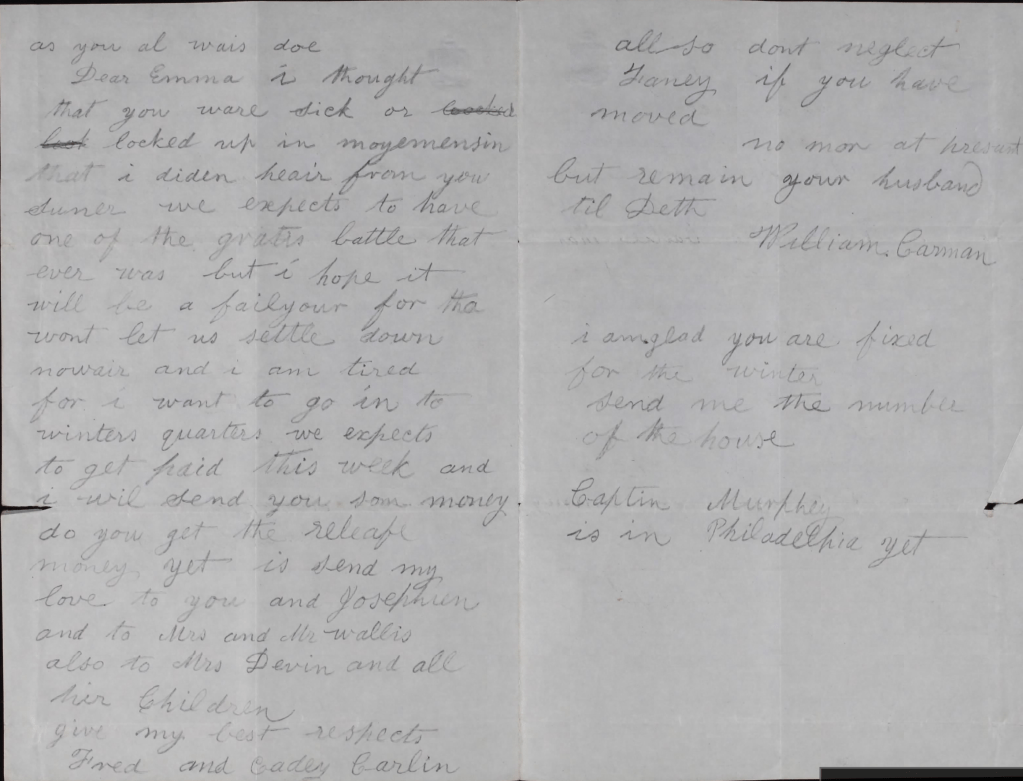

Letter 14

Virginia

November 15, 1862

My dear wife,

Your kind letter dated the 8th inst. came to hand and I am glad to hear that you are well. We have been on heavy marching ever since the first of the month. My instep hurt me very much. We have just camped. I don’t know the name of the place but it is in Virginia. I can see the Blue Ridge Mountains very plain. We won’t be here long.

Your letters I get sometimes on the road as we march along but we can’t answer them always. Direct your letter to Washington the same as you always do.

Dear Emma, I thought that you were sick or locked up in my imagination that I didn’t hear from you sooner. We expect to have one of the greatest battles that ever was but I hope it will be a failure for they won’t let us settle down nowhere and I am tired for I want to go into winter quarters.

We expect to get paid this week. I will send you some money. Do you get the relief money yet? I send my love to you and Josephine and to Mr. and Mrs. Wallace. Also to Devin and all his children.

Give my best respects to Fred and Cody Carlin. Also don’t neglect Fanny if you have moved. No more at present but remain your husband till death. — William Carman

I am glad you are fixed for the winter. Send me the number of the house. Captain O’Murphy is in Philadelphia yet.

Letter 15

Camp near Fredericksburg, Va.

November 30, 1862

My dear wife,

Your kind letter dated the 20th inst. came to hand this morning and I am glad to hear that you are all enjoying yourselves. We have been on the march ever since the first of the month. We are near Fredericksburg, Virginia. Here we expect to have a great battle before long. I think they will shell the city before they can take it. The rebels are on one side of the river and we are on the other.

The weather is very nice but I don’t think I can get home for some time yet for our pay master ain’t made his appearance yet. I wish he would come so I could send you some money before Christmas.

Dear Emma, I wish you would send me twenty-five cents and soon as I get paid I will send you some money.

Our pickets talks to one another across the river. There are three hundred thousand rations drawn here every day for the soldiers.

I send my best love to you and Josephine. Also to Mr. and Mrs. Wallace. Give my best respects to Fred and Frank. Also to Cody Carlin when you see him. I haven’t hear nothing from Baltimore yet.

Write soon as you get this and don’t forget to send me twenty-five cents for I want to get some tobacco. No more at present. Your husband, — William Carman

Direct your letter as before.

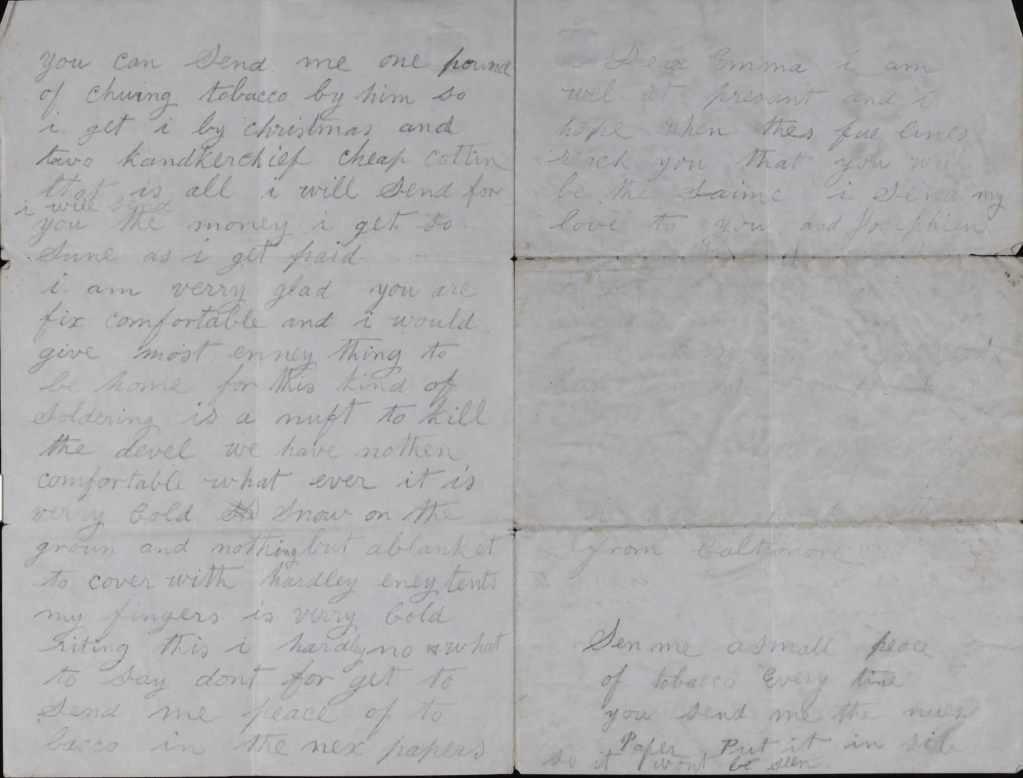

Letter 16

Camp Front of Fredericksburg, Va.

December 7, 1862

Dear Emma,

Your kind letter I received this morning and I am very sorry to hear that you were sick. The papers all came to me and the stamps. Please send me one small piece of tobacco in the next papers you send me so I get it this day week.

There is a young man in our company named Allen who told me that his son would come out with Captain O’Murphy in about two weeks and his name is Allen. Lives at 505 Catherine Street. He will call to see you. You can send me one pound of chewing tobacco by him so I get it by Christmas and two handkerchiefs of cheap cotton. That is all. I will send you the money U get as soon as I get paid.

I am very glad you are fixed comfortable and I would give most anything to be home for this kind of soldiering is enough to kill the Devil. We have nothing comfortable whatever. It is very cold, snow on the ground, and nothing but a blanket to cover with, hardly any tents. My fingers is very cold writing this.

I hardly know what to say. Don’t forget to send me a piece of tobacco in the next paper.

Dear Emma, I am well at present and I hope when these few lines reach you, that you will be the same. I send my love to you and Josephine. Send me a small piece of tobacco every time you wend me the newspaper. Put it inside so it won’t be seen.

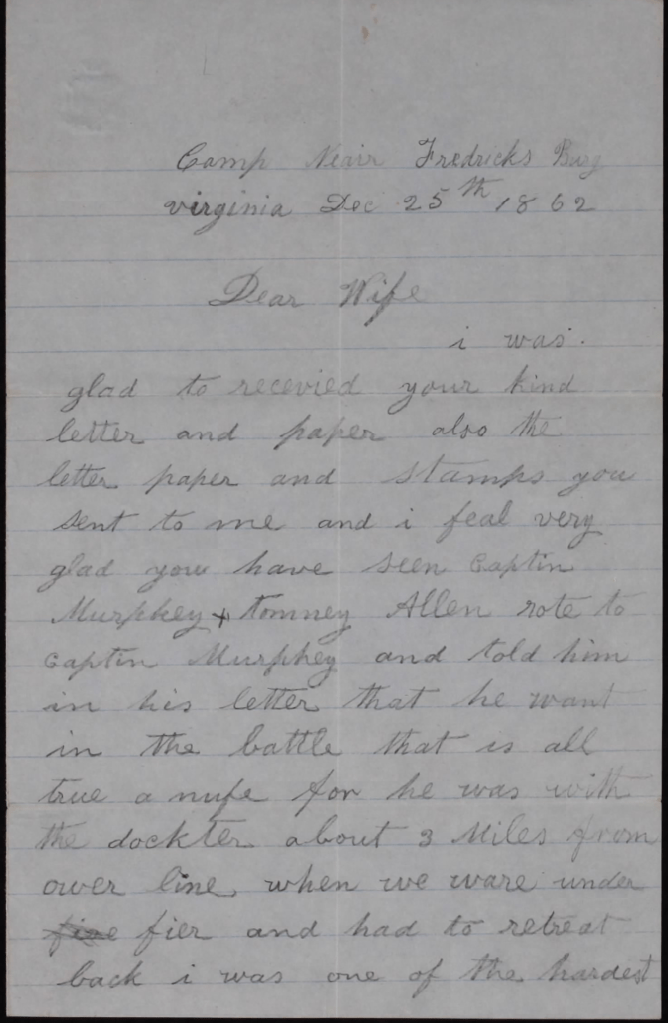

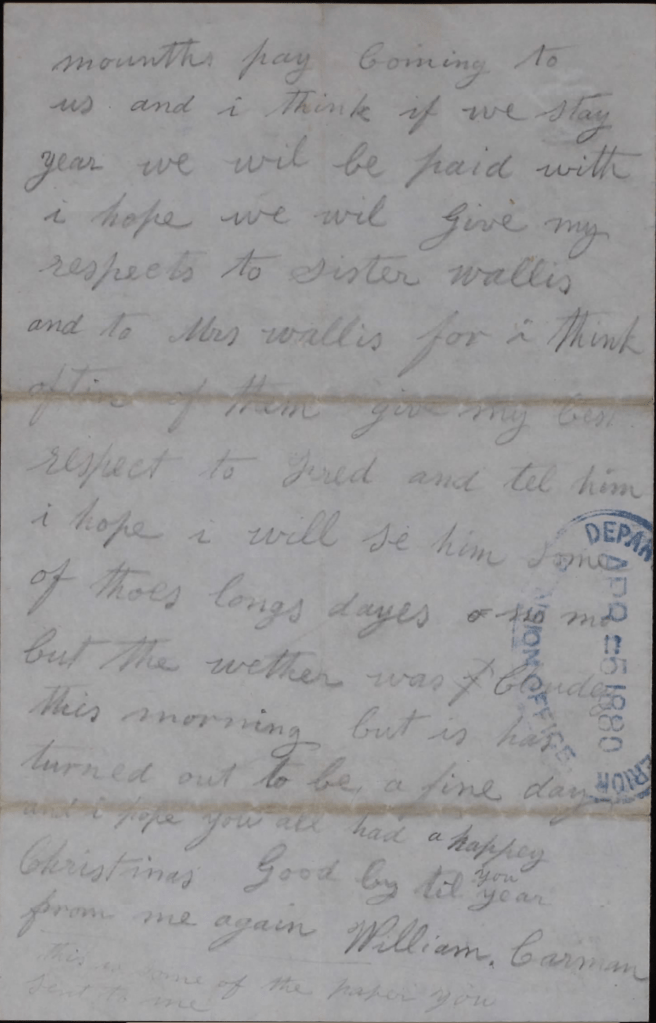

Letter 17

Camp near Fredericksburg, Va.

December 25, 1862

Dear Wife,

I was glad to receive your kind letter and paper. Also the letter paper and stamps you set to me. And I feel very glad you have seen Captain O’Murphy and Tommy Allen wrote to Captain O’Murphy and told him in his letter that he wasn’t in the battle. That is all true enough for he was with the doctor about three miles from our line when we were under fire and had to retreat back. It was one of the hardest fought battles we have had yet. Men that had been in all of the battles said it was—-just at this moment the Sergeant brought me another letter dated the 22nd inst. from you. Don’t send me no gloves for I have got a pair from the government. Don’t rob yourself to send me anything. You can send me a pipe as I lost the one you bought me and the handkerchiefs. Don’t send me any more papers that cost 8 cents for it is too much to pay for them.

I have been very sick since I wrote to you last but thank God, I have got well once more. This is Christmas Day and all we have for breakfast is one cup of coffee and hard crackers is all we got. It is a very poor Christmas for the soldiers. They can get nothing for love nor money for there are no places to buy anything.

You can give my best respects to Captain O’Murphy when you see him. The men would all like to see him. Our Col. [Robert Emmet] Patterson ain’t been with us for some time and I don’t think he will be with us anymore. Our Colonel’s name is [William] Olmstead now. 1

I send my love to you and Josephine and soon as I get paid, I will send you some money. There is four months pay coming to us and I think if we stay here we will get paid. I hope we will. Give my respects to sister Wallace and to Mr. Wallace for I think often of them. Give my best respects to Fred and tell him I hope I will see him some of these days. The weather was coudy this morning but it has turned out to be a fine day and I hope you all had a happy Christmas. Goodbye till you hear from me again, — William Carman

This is some of the paper you sent me.

1 Lt. Colonel William Omstead commanded the 115th Pennsylvania at the Battle of Fredericksburg due to the absence of Col. Patterson.

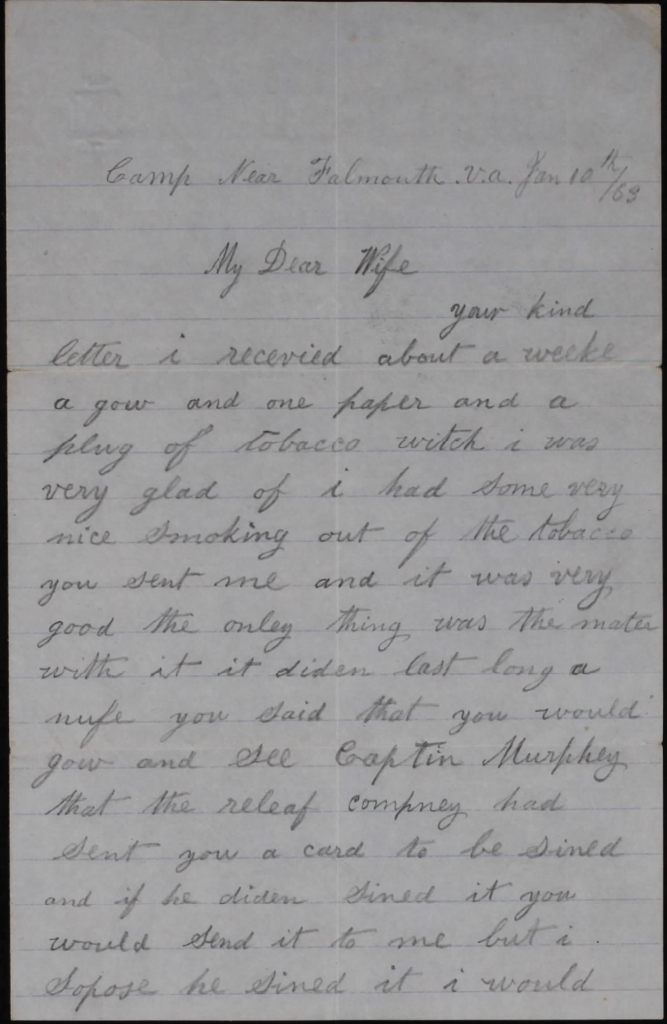

Letter 18

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

January 10th 1863

My dear wife,

Your kind letter I received about a week ago and one paper and a plug of tobacco you sent me and it was very good. The only thing the matter with it was it didn’t last long enough. You said that you would go and see Capt. O’Murphy that the relief company had sent you a card to be signed and if he didn’t sign it, you would send it to me. But I suppose he signed it. I would have wrote to you sooner but I was waiting to hear from you about the card. You must try and learn when Capt. O’Murphy is coming out so I will get the tobacco he has. I don’t think he will be out here for some time and if he don’t come soon, you can get it and send it by Express if they will bring it. Also send me a pipe to smoke.

Our lieutenant is sick and he is going for to leave us and go home. I think he got enough of soldiering. 1

I wrote in the last letter to send me the Inquirer or the Sunday Dispatch whenever you could. They are cheaper than those other papers and just as much news in them. I send you a letter I got from my sister which you can read, Fred Edwards is very lucky in getting home.

I am well at present and we expect to get paid soon and I will send it to you for I know that you must want some money. I send my love to you and Josephine and to sister Wallace and to Mr. Wallace. I think of you all every day and night.

Mrs. Devine is very good to you in answering your letters. Give my best respects to her. Please send me a postage stamp in your next letter as I haven’t none. No more at present but remain your affectionate husband, — William Carman

1 Probably 2nd Lieutenant William H. Lechler who was discharged on 30 January 1863, although 1st Lieutenant Michael J. Dunn was also discharged on 11 February 1863. John Blair was promoted to 1st Lieutenant from Commissary Sergeant on 1 May 1863.

Letter 19

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

January 16, 1863

My Dear Wife,

Your kind letter dated the 10th inst. I just received this morning and I was very happy to hear that you was well. I received the tobacco you sent me and was very glad of it. We are now building our log cabins for to go into winter quarters but I don’t think we will remain in them very long.

Dear Emma, I know it is very hard to get money and it seems harder to me that they don’t pay the soldiers so they could send their money home to their wives. But as soon as I get paid, I will send it to you for I know you must want it now. It is nearly five months since they paid us and I think it is pretty near time that we were paid as they promised to pay every two months which they don’t.

Don’t forget to send me the pipe. If Capt. O’Murphy don’t come out soon, you send it by mail in a paper. Get a nice light one like the one you got before and I am a thousand times obliged to you for sending me the twenty-five cents and four postage stamps for I had none.

I am well and send my love to you and Josephine…No more at present but remain your husband till death, — William Carman

P. S. If Captain O’Murphy ain’t out in ten days time, you will please send the pipe to me by mail and fill it full of tobacco so I will have a nice smoke when I get it and be thinking of home at the same time and the one that is so dear to me.

Letter 20

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

February 9, 1863

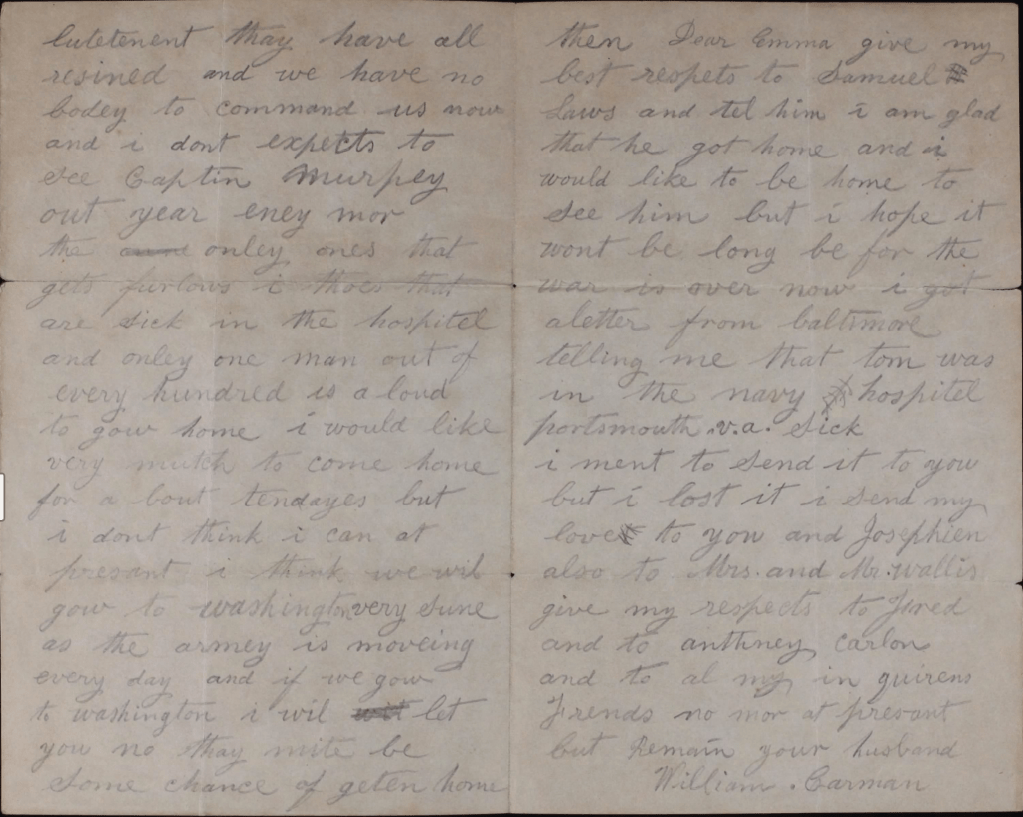

Dear Wife,

Your kind letter reached me this morning and I was glad to hear that you were well. I also got the paper and tobacco and the postage stamps and I am very thankful to you for sending them to me. Our pay master ain’t paid us off yet but soon as he does, I will send you some money for I know you want it.

Dear Emma, it is very hard to get a furlough in our company as we have no captain or lieutenant—they have all resigned—and we have nobody to command us now. I don’t expect to see Capt. O’Murphy out here anymore. The only ones that get furloughs is those that are sick in the hospital and only one man out of every hundred is allowed to go home. I would like very much to come home for about ten days but I don’t think I can at present. I think we will go to Washington very soon as the army is moving every day and if we go to Washington, I will let you know. There might be some chance of getting home then.

Dear Emma, give my best respects to Samuel Laws and tell him I am glad that he got home and I would like to be home to see him but I hope it won’t be long before the war is over now.

I got a letter from Baltimore telling me that Tom was in the Navy Hospital at Portsmouth, Va. [N. H.] sick. I meant to send it to you but I lost it. I send my love to you and Josephine…No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman

Letter 21

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

February 17th 1863

My dear wife,

Your kind favors came to hand this morning and I am always glad to hear from you and to know that you are well and also I hope that Josephine will take good care of herself and save her money and not spend it foolish for money is very hard to get now—even when earned. For my part, I think they treat the soldiers very bad for they only pay the men when they see fit where they ought to get paid every two months. However, don’t send me anything more that will cost so much postage till I send you some money which I hope won’t be very long.

We are still in our log houses yet. We expect to move shortly. We have very little time for ourselves as our company is very small—only 12 men. I heard from Capt. O’Murphy yesterday saying that he would leave on Monday night at 11 o’clock for to take charge of his company but I don’t think he will. The weather is bad for it is snowing and I got to be out all night.

Dear Emma, I’m very much obliged to you for sending the handkerchief but I would [have] liked it much better if it had been colored. But it is a good handkerchief.

You give my respects to Sam and tell him I am very glad he has got home.

I send my love to you and Josephine…No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman

Letter 22

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

March 1, 1863

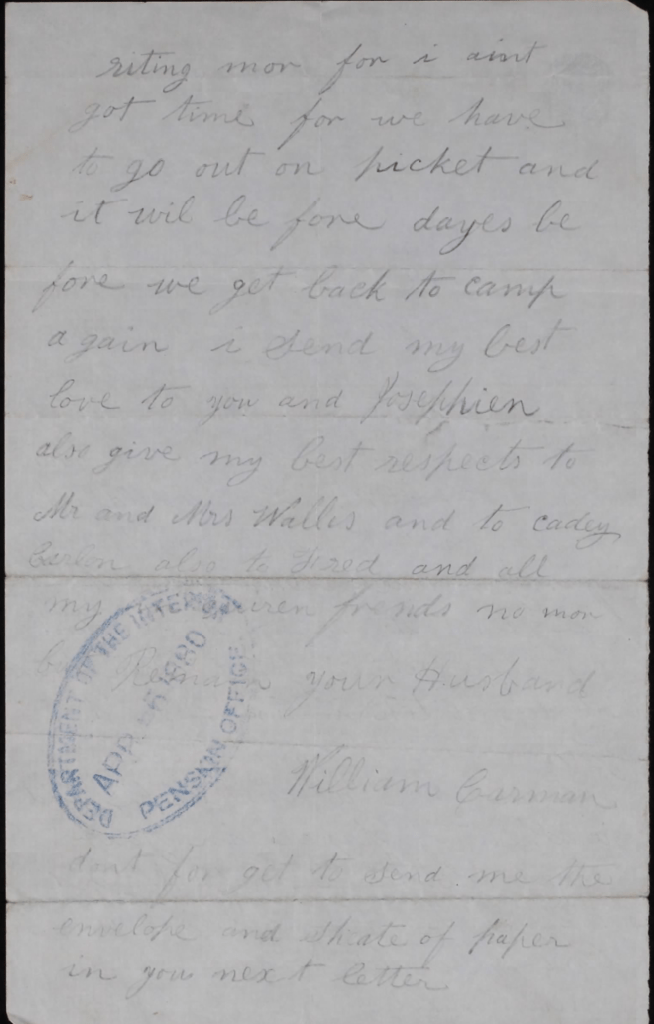

Dear wife,

We got mustered in for pay yesterday and we will get paid about the middle of this month and then I will send you some money so you can get what you would like. I dreamed the other night that [our dog] Fanny came running into the tent to me and I couldn’t get her out. I got a letter from sister which I enclose to you.

Dear Emma, please send me an envelope and a sheet of paper in your next letter. I am well and I hope these few lines will find you the same. You must excuse me for not writing more for I ain’t got time for we have to go out on picket and it will be four days before we get back to camp again.

I send my best love to you and Josephine…No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman

Letter 23

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

March 14th 1863

Dear Wife,

Your kind favors I received and was glad to hear from you and all of my friends and would like to be at home for to see you all once more but we have no captain and we have no chance to get a furlough at present. But soon as we get paid, I will try to get one for ten days. There are very few men get furloughs in our regiment. They are most all officers that get them.

Dear Emma, I heard from [brother] Thomas. He has got home but didn’t get no pay yet. He says he is going to work. He sends his best respects to you and Josephine.

I think we will move soon as it is all the talk but we don’t know where. We are kept very busy. Hardly any time to wash a shirt. We are all the time doing something. The roads is very bad. I will have to stop for I got to go after wood. I send my love to you and Josephine. I will send you some money next week if the pay master comes. Give my best respects to all my friends. I’m very sorry that Frank Spicer drank himself to death. If he had been out here, he might have been living yet. I don’t drink any more. No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman

I think you may look for some cash in your next letter.

Letter 24

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

March 23, 1863

Dear wife,

I received your kind letter and was glad to hear from you and all my friends and to know that you are well.

Captain [Patrick] O’Murphy is out here but hasn’t taken command of his company yet. He come on the 14th of March. His leg is very bad. I don’t think he ever will be able to take command of us. I would have wrote sooner but thinking the pay master would be here every day so I could send you some money. I hope by the time this reaches you that I may be paid for it has been seven months since I got any money and I know that you must stand in need of some. No more at present but I send you my love to you and Josephine….Very respectfully your husband, — William Carman

P. S. I also send my best respects to Mr. and Mrs. Wallace. Some of the soldiers is betting that the war will be over in two months but I hardly think it will. Write soon as you can and let me know how the times is in Philadelphia. No more. — William Carman

Letter 25

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

April 11, 1863

Dear wife,

It gives me great pleasure to have the chance to write to you and let you know that I am well at present, hoping these few lines will find you the same. I haven’t much to say but I would like to be home and see you for it seems to me a long time and it will be as long again before I get my discharge.

Our regiment has been just eighteen months in service but I will try to get a furlough soon as the pay master pays us. He ought to have been here long ago but hasn’t come yet. They will owe me eight months pay this month and I think it very hard that we don’t get paid. But I hope they will pay us soon now as they say they will.

Mr. Allen’s little boy is out here with Capt. O’Murphy and will leave for home next week and will call and see you.

Dear Emma, please send me two or three postage stamps as they are hard to get here and as soon as I get paid, I will send you some money for I know you want it for it vexes me every day for to think that they don’t pay me. I only can send my love to you and Josephine and all my enquiring friends. No more at present, but remain your dear and affectionate husband, — William Carman

My letter hereafter will be directed to you as Mrs. William Carman.

Letter 26

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

April 17, 1863

Dear Wife,

I received your letter with the likeness last evening as we were getting paid and was glad to hear you are well as I am to be able to send you some money. I send you $30 by Adams Express which you will call and get at the Office as soon as you receive this. I would have sent you more but we did not get paid in full. We are to get paid every two months from this time.

We are to march every hour and know not where we are going to. I am on guard and cannot get a chance to write myself.

I cannot send it by Express so I will enclose it in this letter. I am well as usual. Yours, &c. — Wm. Carman

Write soon. Very seldom I get ink.

Letter 27

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

Monday morning, April 27, 1863

My dear wife,

Your kind letter I received and was glad to hear you got the money I sent you. They didn’t pay me only one half that was coming to me. If they had paid me all, I could have sent you seventy-five dollars but as it is, I couldn’t. They say they will settle up with me the first of January but if I live I will be home before that. I didn’t keep no money for myself for I knew that you must stand in need of all I sent…

We have got to go on picket this morning at 7 o’clock and it is near that time. Now write soon as you get this. No more at present but remain your husband, — William Carman

Thee is no news yet but expect to mover every hour.

Letter 28

Hospital 2rd Division, 3rd Army Corps

Potomac Creek

May 16, 1863

Dear Wife,

I received your letter of the 30th yesterday. I was wounded in the Battle of Chancellorsville on the 3rd of the month by a gunshot in the left hip besides three slight wounds on the same leg. I am in no danger and not much pain. I expect this hospital will be broken up and we will be sent to our respective states in a short time.

You mention that you sent me a handkerchief and some papers, I have not got them yet.

Out of our company we lost 2 killed and three wounded and two missing. I will close by sending my love to you and Josephine. I hope to see you soon. I remain yours, — Wm. Carman

Write soon. Direct to the regiment. I will get it.

Letter 29

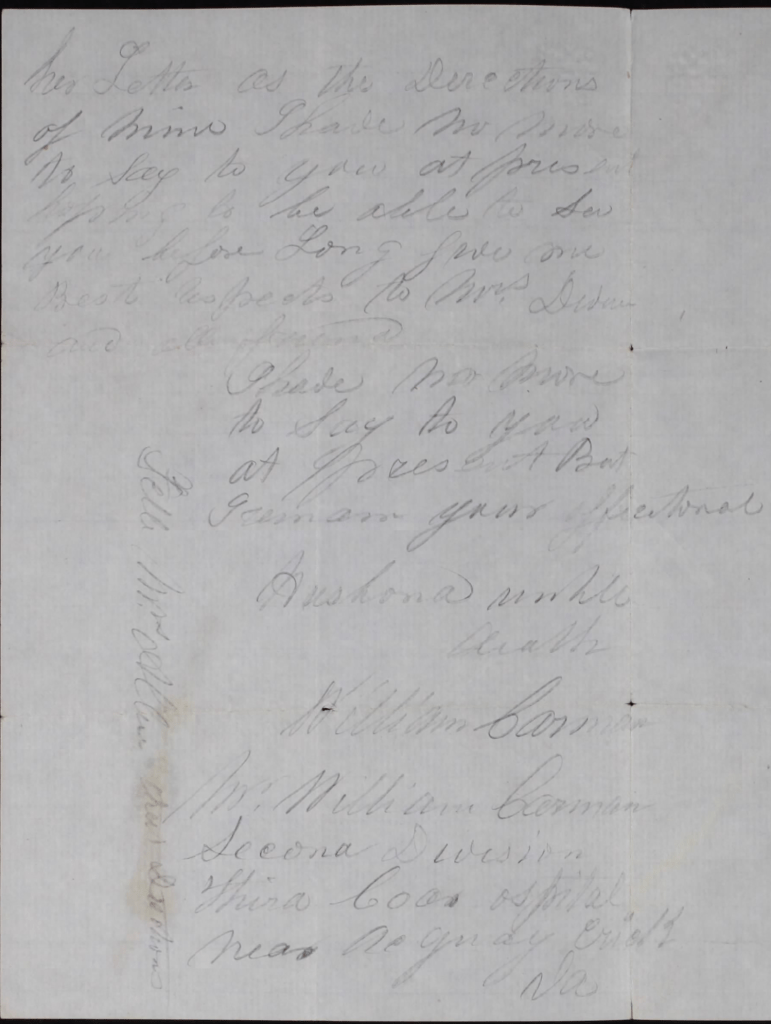

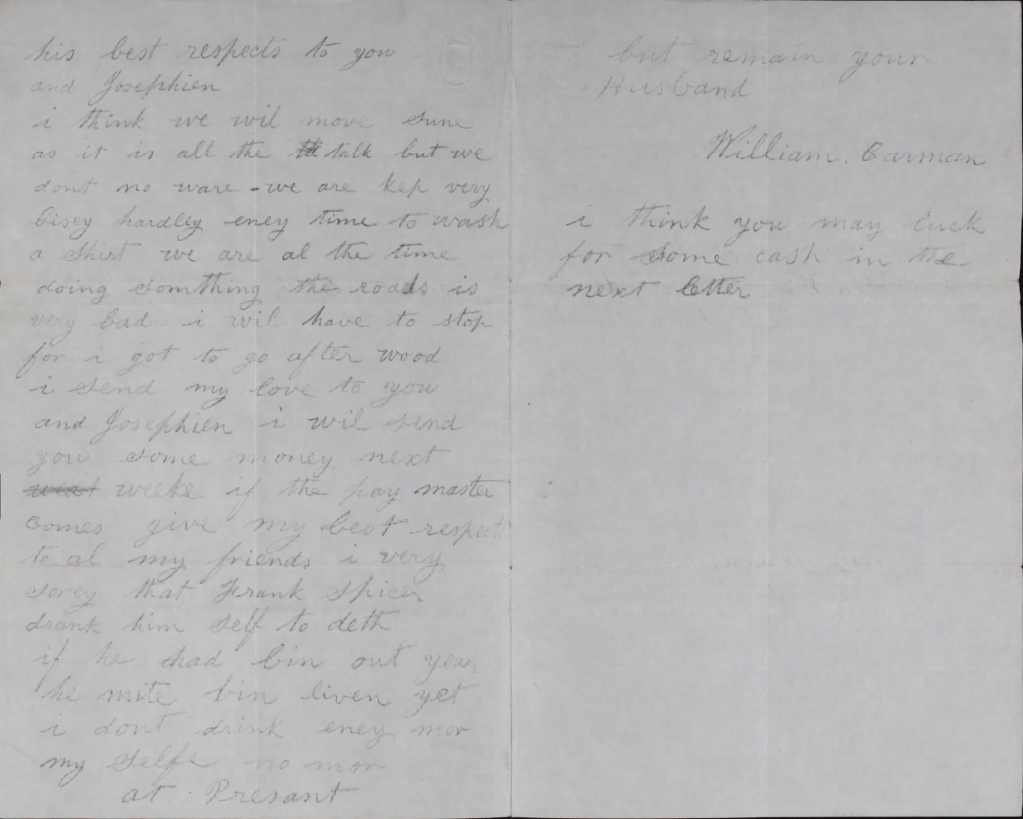

[written by some hand other than William’s]

Camp near Falmouth, Va.

Hospital about a mile from camp

May 29th 1863

My darling and affectionate wife,

I received your letter this day by my friend Thomas K. Allen which I am glad to hear that you are well and in good health. Thanks be to God, I am in good spirits myself. My wound is getting better. We expect to be going to Philadelphia in a few days. They say that the regiment will be going home to recruit again and take the sick to Philadelphia where they will be treated better than they are here.

We expect to be paid 3 months pay on Monday. I will send you some home then…I have no more to say to you at present but I hope that I will be home soon. Mr. Allen is well and all the boys—only the two that was killed—[Patrick] Ward and[Richard] Thunder. God be with them.

I am your affectionate husband until death, — William Carman

N. B. Goodbye but not for ever. Kiss this in memory of me.

Letter 30

[written by some hand other than William’s]

Second Division, Third Corps Hospital

Near Aquia Creek, Va.

June 6th 1863

Dear Wife,

I write these few lines to you hoping to find you in good health only I am not out of bed yet. My furlough I have ready to put in and I hope to get home in a few days. There was two of our regiment went home this day. I have not received them handkerchiefs. I do not know what is the reason, I do not know. Thomas K. Allen is here doing duty at the Provost Marshall’s. He is a great comfort to me. He comes twice a day to see me. Tell his wife he is here and tell her to direct her letter as the directions of mine. I have no more to say to you at present. Hoping to be able to see you before long. Give my best respects to Mrs. Diven and all friends.

I have no more to say to you at present but I remain your affectionate husband until death, — William Carman