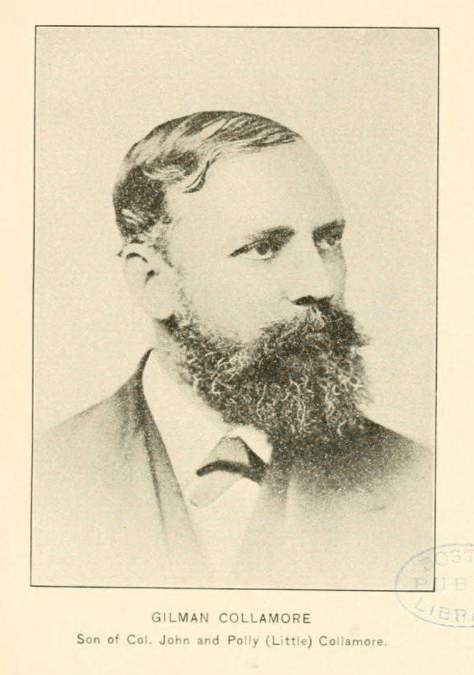

These letters were written by Gilman Collamore (1834-1888), the son of Col. John and Polly (Little) Collamore of Boston, Massachusetts. He wrote the letter to his brother John Collamore who was living in Paris, France, during the American Civil War. The Collamore family rivaled Tiffany’s as New York City importers for the wealthy of fine British porcelain, china and glass, as well as elegant American cut-glass and pottery.

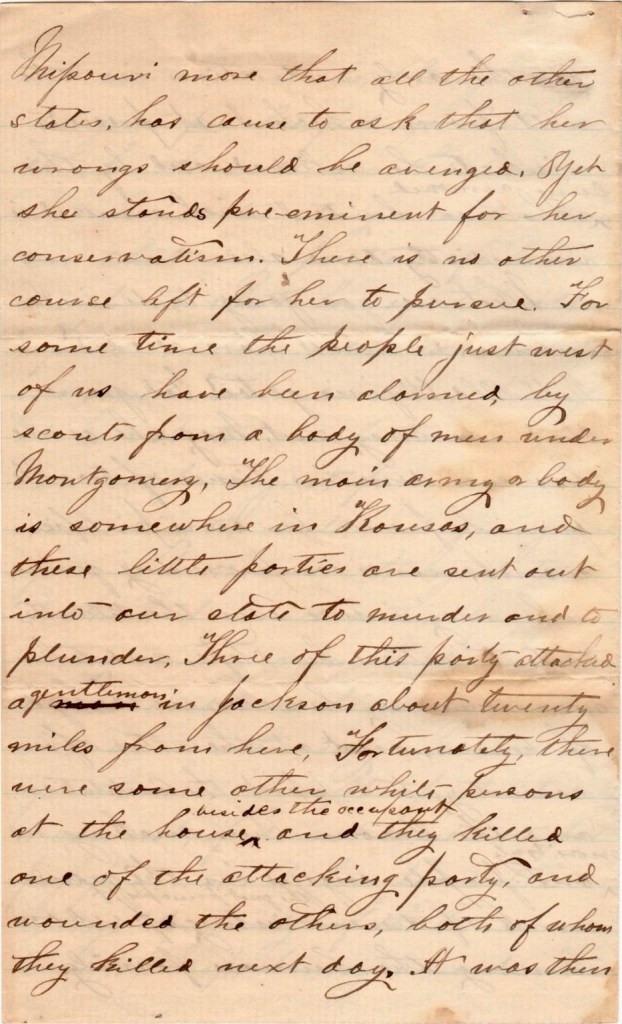

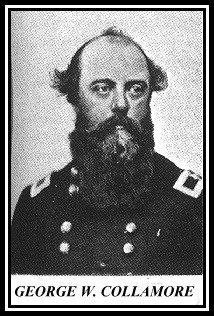

But Gilman and John Collamore’s older brother, George Washington Collamore (1818-1863), chose a distinct path from his siblings. George became a Boston lawyer, forming a partnership with John A. Andrew—the future Civil War Governor of Massachusetts. Like Andrew, a fervent Abolitionist, Collamore relocated his family to “bleeding Kansas” in 1856 and assumed the role of agent for the New England Kansas Relief Committee, which provided essential supplies to Kansas emigrants amidst their violent struggle against pro-slavery forces. With the onset of the Civil War, George was commissioned as a brigadier general and tasked with equipping Kansas volunteer regiments for the Union Army. Subsequently, he was elected Mayor of Lawrence, Kansas—a pro-Union stronghold for anti-slavery emigrants. He believed that the town, with its staunchly pro-Union populace, would be sheltered from the hostilities that had plagued the state. However, on August 21, 1863, Confederate Raiders—criminals and outlaws organized into a ruthless guerrilla force by William Clarke Quantrill, a pre-war slave-catcher—assaulted Lawrence, resulting in the deaths of 150 men and boys while targeting the despised Collamore.

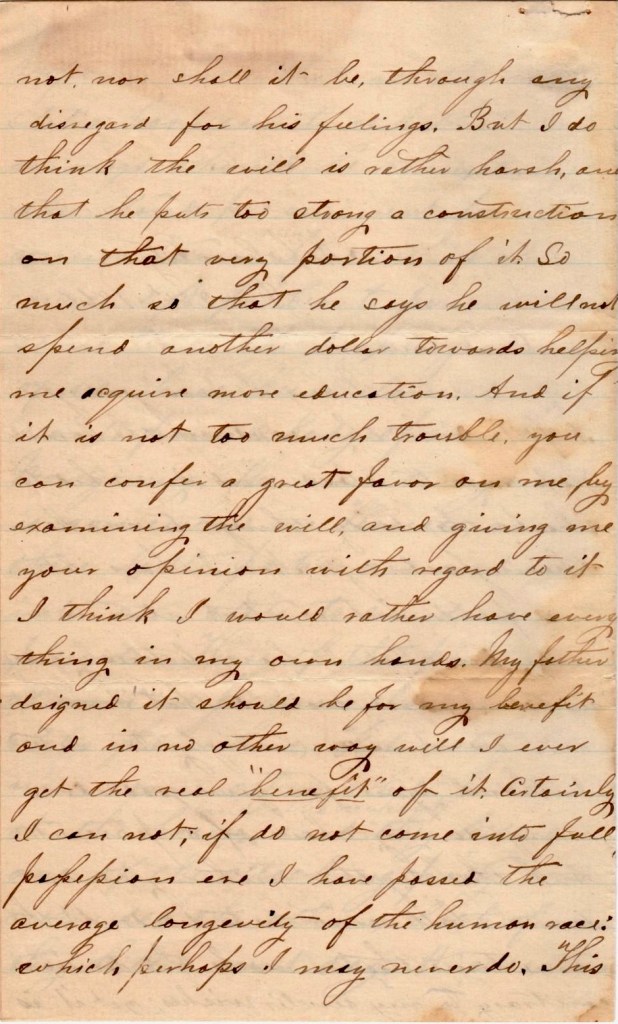

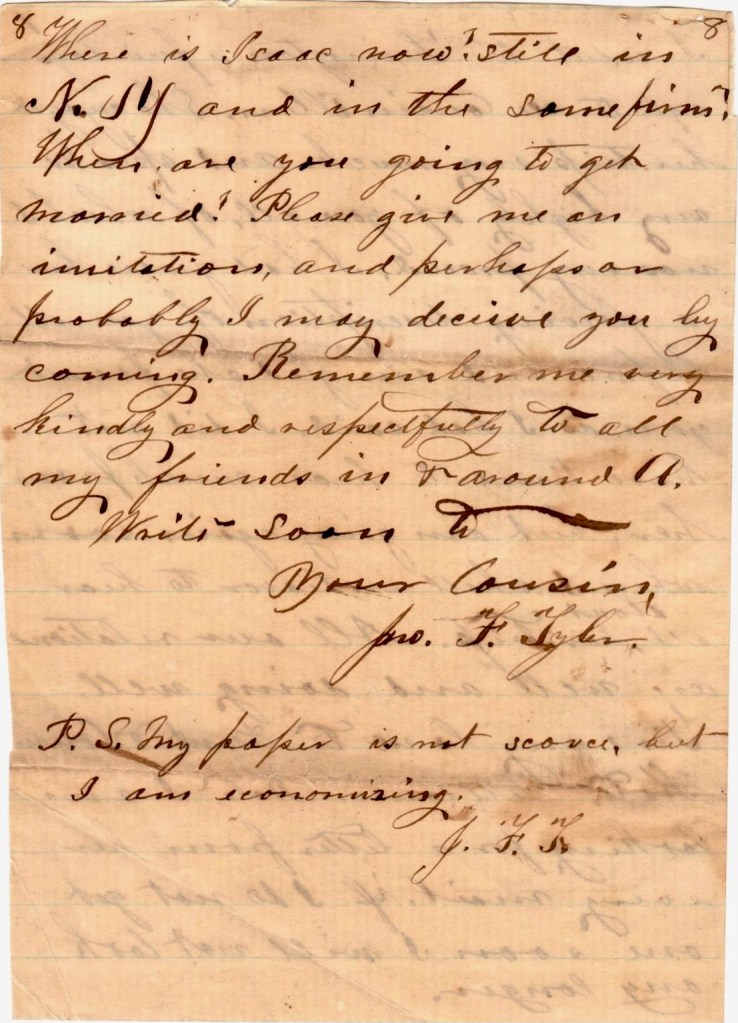

On August 26, Gilman conveyed the first of a series of somber letters to his brother John in Paris, delivering the “sad and distressing” news, conveyed by Governor Andrew, regarding the death of their brother George. George’s son Hoffman had sustained serious injuries and their property had been devastated. “This loss has completely unmanned me,” Gilman expressed, “I cannot believe we could be called upon to mourn his loss so soon.” A week later, Gilman wrote once more, filled with sorrow and bewilderment, recounting the “sad, sad day” of George’s funeral after his remains had reached Boston, accompanied by his widow and wounded son. He provided a brief account of George’s demise, suffocated while hiding in a well dug into the cellar floor as his house was engulfed in flames by “ruffians.” Having seen him only a few weeks prior, Gilman had implored George not to return to Kansas, but George was resolute, insisting he had business there that required his attention. In a third letter, composed at the end of September, Gilman delivered a long, detailed, and tragically dramatic account, detailing the “full particulars” of how George’s son, shot from his horse, narrowly escaped death at the hands of 20 guerrillas masquerading as Union troops, sent with the intent to locate and murder his father, followed by Mrs. Julia Collamore’s personal account of how her husband met his untimely end.

See also—1863: Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence

[Note: These letters are from a private collection (RM) and were offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Letter 1

Boston [Massachusetts]

August 24th 1863

My dear brother John

I was very glad to get the letter of June & July & should have answered them before but was in the country at the time for my health which of late has not been what I could wish. I note particularly the contents but they are at home. I will answer them in my next for I am too unwell & sad to do so now.

My purpose in writing at this time is to give you the sad & distressing news of the death of our brother George in Kansas, the particulars of which we only know from the enclosed paper and also two telegrams received—one from Lawrence & another from Leavenworth, Kansas. I have seen Gov. Andrew & he showed me the telegrams which are to the purport that George was killed & his son Hoffman seriously wounded & would probably die, & that their property has been destroyed.

Six weeks since our brother was in Boston perfectly well & happy & he and I were together several hours & was to return to Kansas the next day. I cannot reconcile myself to this severe loss, taken out of the world in perfect health & without warning. I had talked to him a great deal about going back. I wanted him to stay here until the troubles in that part of the country was settled, but he told me that he did not fear anything serious in Lawrence. Gov. Andrew has telegraphed to Kansas to know what is needed & I have suggested someones going on, & tomorrow or next day we shall decide what is best to be done.

The family has our sympathy in this their sad misfortune. I shall tender to them all the aid I can do and hope they will try to bear up under the severe affliction. Oh my dear brother, this loss has completely unmanned me. I cannot believe we could be called upon to mourn his loss so soon. All send their love while in distress. Your affectionate brother, — Gilman

Letter 2

Boston [Massachusetts]

September 4, 1863

My dear Brother,

Yesterday was a sad, sad day to us all. We paid the last tribute to the remains of our dear brother; how can I write to you in any intelligent way when my heart is so full of sorrow & my mind so bewildered. But I must nerve myself to the task. Oh God, spare me from the lot.

The remains of our dear brother arrived here day before yesterday with his family which I was expecting hourly. I called upon them at once to sympathize with them in their sore affliction. It was a speechless meeting for some time. We could but give vent to tears & lamentations; the recital of brutal murder which is announced in the papers cannot but faintly give you the horrors of the scenes enacted at Lawrence.

Our dear brother did all he could do to protect himself and family and at last went into his well for safety where he would have been safe if his home had not been fired. The ruffians set fire to his house which was contiguous to the well & there he was suffocated. Oh can it be possible that I am not to see him again? Only two months since he was with me & spent some two hours with me. I told him not to go back to Kansas. He said their home is there which I must attend to. “Oh George,” said I, “I would not go there if you were to give me the whole of Kansas.” He said he should be back again in three or four months. Oh how little he thought of the mysterious ways of Providence. We know not what a day may bring forth.

Oh my dear brother, I hope you will have strength to stand up under the severe trial & may God spare your life many years. I could write you much more if my strength would allow me but I must close as by another steamer. I only wish you was here that I might join in assisting you to bear up under this heavy burthen. God give you strength to do so. All send their love & sympathy in this our day of gloom. Your affectionate brother, — Gilman

Excuse this letter

Letter 3

Boston [Massachusetts]

September 24, 1863

My dear brother John,

I have this day received your letter without date acknowledging the receipt of mine of August 24th coneying to you the sad news of the death of our dear brother. I have written to you four letters, all of which I hope you have received before this, which will give you full particulars relating to our brother’s decease, burial, &c.

If a few should not reach you, I will write you again in full as you desire. The raid into Lawrence was made at day break on the morning of the 21st August. Hoffman, early on the morning of the 21st, went out on horseback a gunning and had proceeded about a mile from the house when he came up with 15 to 20 men on horseback dressed in U. S. soldiers uniforms riding into Lawrence and who he took to be U. S. soldiers but who proved to be guerrillas. They ordered him to halt, which he did, and at that instant they fired their revolvers at him, the balls whistling all about him, one of which took effect in his leg, wounding him severely & several striking his horse. He feigned being killed and fell from his horse, and as he was falling they fired again, but fortunately missed him. And again, while he was lying upon the ground, they fired point blank at him, but again missed him, and then went on supposing him to be dead. He lay some time upon the ground, when three to four hundred guerrillas came along and passed him, supposing him to be dead and fortunately without firing at him. Soon after they passed him, he crawled to a home nearby occupied by Irish people into which he went, going down cellar & there remained some five hours & from which place he came out from further being harmed.

Mrs. Collamore tells me that our brother attended a railroad meeting the evening before the raid and addressed the meeting for about an hour and that she retired to bed early & before our brother arrived home. But during the night she awoke and found him by her side. Before daybreak she awoke and heard guns firing at a distance. She listened for a time and again heard them, when she awoke our brother & while he was listening, the windows were raised by the guerrillas and demanded to know who lived there. She told them that no one but herself and children. They again demanded to know who lived in the house when she again replied, no one but herself and children, and for a short time they left, seemingly satisfied. When she got out of bed & went to the window and saw them murdering the people all around & told George of what was going on [was] when George jumped out of bed & requested her to give him his pistols while he dressed himself. She begged him not to use them, but told him to get into the closet. He replied that was no place for him, and again asked for his pistols. She then told him to get into the well. He then went down stairs and soon after she followed to see that he was safe, but he had not got into the well. She begged of him to get in. He replied he could not leave her and the children. She begged of him to save himself and she would look after herself and the children.

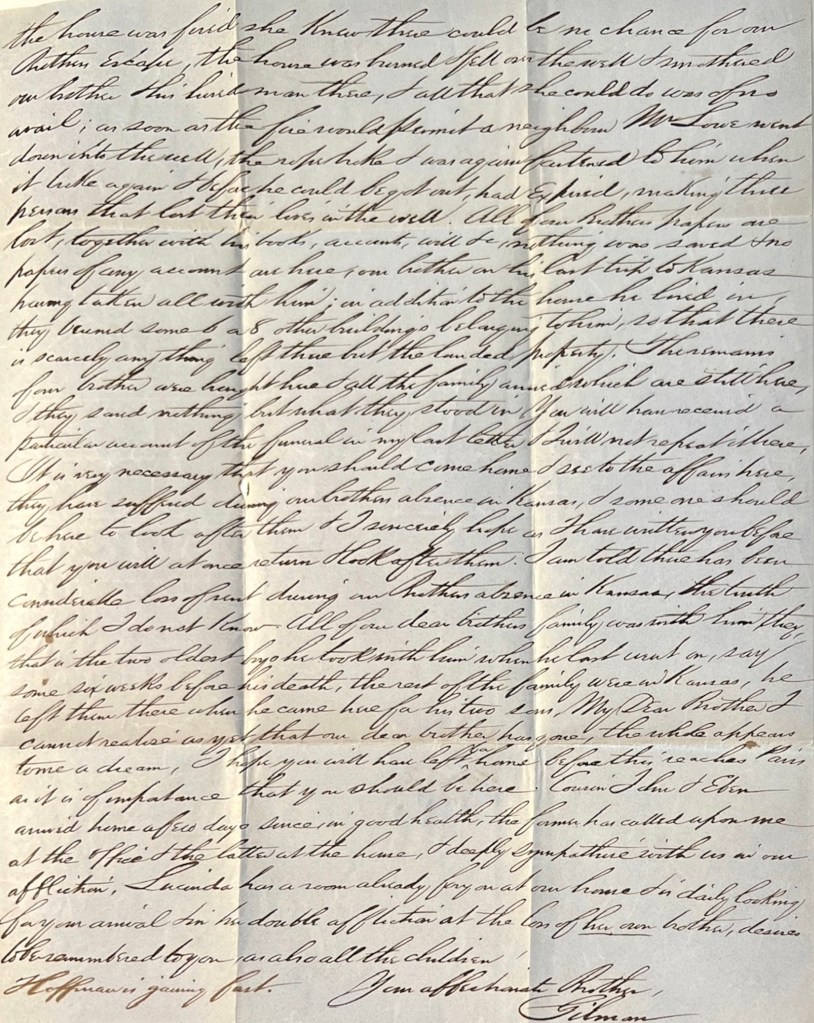

He went down and she returned four different times to see if he was safe and he answered her every time that he was. When they broke into the home—some 30 to 50—and pointed their pistols at her head and one of the children and demanded to know where Mr. Collamore was, she replied he has gone East. They told her she lied and with an oath demanded to know where Mr. Collamore was. She again replied that he had gone East. They then demanded the money & what was in the home she gave up. They then searched the house and turned things upside down and took what they wanted and down stairs piled up all the combustible things they could lay their hands upon and fired the house in a dozen different places and she and the children ran out as best they could. And from the time the house was fired, she knew there could be no chance for our brother to escape. The house was burned and fell on the well and smothered our brother and his hired man there, and all that she could do was of no avail. As soon as the fire would permit, a neighbor—Mr. [Joseph] Lowe—went down into the well. The rope broke and was again fastened to him when it broke again and before he could be got out, [he] had expired [too], making three persons that lost their lives in the well.

All of our brother’s papers are lost, together with his books, accounts, will, &c. Nothing was saved & no papers on any account are here, our brother, on his last trip to Kansas having taken all with him. In addition to the home 1 he lived in, they burned some 6 or 8 other buildings belonging to him so that there is scarcely anything left there but the landed property.

The remains of our brother was brought here and all the family arrived, which are still here, and they saved nothing but what they stood in. You will have received a particular account of the funeral in my last letter. I will not repeat it here. It is very necessary that you should come home & see to the affairs here. They have suffered during our brother’s absence in Kansas & someone should be here to look after them & I sincerely hope as I have written you before, that you will at once return & look after them. I am told there has been considerable loss of rent during our brother’s absence in Kansas, the truth of which I do not know. All of our dear brother’s family was with him. They—that is, the two oldest boys he took with him when he last went on, say some six weeks before his death. The rest of the family were in Kansas. He left them there when he came here for his two sons.

My dear brother, I cannot realize as yet that our dear brother has gone. The whole appears to me a dream. I hope you will have left for home before this reaches Paris as it is of importance that you should be here. Cousin John & Eben arrived home a few days since in good health; the former has called upon me at the office and the latter at the house, & deeply sympathetic with us in our affliction. Lucinda has a room already for you at our home & is daily looking for your arrival & in her double affliction at the loss of her own brother, desires to be remembered to you as also all the children. Your affectionate brother, — Gilman

Hoffman’s 2 gaining fast.

1 The location of George W. Collamore’s home has recently been determined to have stood at the northeast corner of Sixth and Louisiana Streets in Lawrence. It was totally consumed by fire according to Mrs. Collamore’s account. See Anniversary of Quantrill’s Raid.

2 John Hoffman Collamore (1846-1865) was wounded by a shot from Quantrill’s band of raiders. He was a target for many bullets as the raiders passed his body lying by the roadside and his clothing was full of holes, but the first shot was the only shot that penetrated his flesh. Soon after this event he enlisted as a private in a Kansas regiment. When 19 years of age he was appointed second lieutenant in the 3rd Regiment Massachusetts Heavy Artillery, mustering at Boston October 14, 1864. He was made first lieutenant September 1, 1865 and saw much rough service with the Army of the Potomac. On one occasion he succeeded delivering an important message, after six other men had been shot from their horses in making the same attempt. Being a large robust man he had no fears for disease that took away many of his fellow officers. However, he finally succumbed to a malignant fever and was sent North, where he died on September 17, 1865.