This journal was kept by Lavinia Murray (1818-1896), the daughter of William W. Murray (1784-1865) and Mary Crawford (1800-1853) of Middletown, Monmouth county, New Jersey. Lavinia commenced her journal on 24 May 1834 when she was 15 years old. Her last entry, on the last page of the journal, was dated in 1842 when she 23. She married James M. Hoagland (1818-1857), a New York Merchant, on 26 August 1847 and resided in New Jersey or New York City the remainder of her life, leaving no children. She died in 1896.

Lavinia was the oldest of three children. Her siblings were Eleanor Crawford Murray (1821-1858) and George Crawford Murray (1827-1884). George graduated from Yale in 1845, studied law in New York City and was admitted to the bar in 1849 but gave up law to manage two family farms. [Source: The Scott Family of Shrewsbury, page 20]

The following biographical sketch of the Murray family, most of it devoted to Lavinia’s younger brother, George, appears in Monmouth County Archives, published in 1917.

Lavinia’s father, “William W. Murray, son of William and Anna (Schenck) Murray, was born November 30, 1794, and died June 1, 1865. His education was the ordinary one of a country school, but he early displayed especial ability as a penman, bookkeeper and accountant. He became associated in business with his father in 1815, the firm name being William Murray & Son, and upon the death of the latter, continued the farming and mercantile interests alone. When the towns of Keyport and Red Bank were developed, all business was taken from Middletown, and the farm was rented to successive tenants, who allowed it to fall into bad condition. For many years Mr. Murray was postmaster of Middletown, and a trustee of the Baptist church, holding this office until his death. He and his wife greatly appreciated the value of a good education, and gave their children the best advantages that lay in their power.

Mr. William W. Murray married, November 20, 1817, Mary Crawford, born January 12, 1800, a daughter of George and Eleanor Crawford; great-great-granddaughter of the first John Crawford, of Middletown; and a descendant of Roelif Martinse Schenck, of Long Island; also of the Rev. Obadiah Holmes, of Rhode Island; and of Sheriff Daniel Hendrickson. Children: Lavinia, married James M. Hoagland, of the Dutch family of that name in Somerset county, New Jersey; Eleanor Crawford, married Henry G. Scudder, of Huntington, Long Island, a descendant of Thomas Scudder, the first emigrant of that name in Salem in 1635; George Crawford Murray, only son and youngest child of William W. and Mary (Crawford) Murray, was born in Middletown, Monmouth county, New Jersey, January 3, 1827, and died there, November 24, 1884. He was but three years of age when his education was commenced in the school conducted by Mr. Austin, in a small building located in Dr. Edward Taylor’s garden, opposite the east side of the Episcopal church, in Middletown. He also studied under Mr. Austin, in the old Franklin Academy. At the age of thirteen years he became a student at the Washington Institute, in New York City, and was there prepared for entrance to Yale College, now Yale University, under the preceptorship of Timothy Dwight Porter. He felt that his especial weakness was mathematics, and with the energy and ambition so characteristic of him from his earliest years, determined to pursue this study by himself. So successful was he in his efforts in this direction that, one year later (1841), he passed his entrance examination to Yale in this branch successfully. September 30, 1843, he received “Professor Playfair’s Works” from the President and Fellows of Yale to George C. Murray, for excelling in the Solution of Mathematical Problems.” In 1845 he was graduated as the youngest member of his class.

By means of living plainly and economically upon the competent allowance he received from his father during his college years, he was enabled to put aside a handsome sum of money which he devoted to the purchase of standard works for a well chosen library. Science and engineering would have been the branches chosen by Mr. Murray had

he followed his own inclinations, and he was eminently fitted to achieve success in these fields. But the wishes of his parents were ever a paramount consideration with him, and it was their desire that he fit himself for either a legal or medical profession. Having decided upon law, he studied for almost a year with Peter D. Vroom, of Trenton, New Jersey, and then with the Hon. George Wood, of New York City, and was admitted to practice in the latter State, January 8, 1849. He then returned to Yale College, and there took a post-graduate course in analytical chemistry, in the new scientific department of the college.

Returning to his home in August, 1850, he again yielded to the solicitations of his parents, who desired him to abandon professional work of any kind, and devote himself to agricultural pursuits. Repugnant as the idea was to his finely trained and developed mind, his filial devotion gained the day and he became a farmer. The energy and earnestness which had characterized his years of study did not fail him in this new field of industry, and he pursued all the distasteful details of farm life with thoroughness and a careful attention to detail, and applied to them original ideas, developed in his scientifically trained mind. Many of these ideas were adopted by others, and some of them changed slightly to meet altered conditions, are in use at the present time. While superintending some work in a marl pit, at Groom’s Hill, on his farm, Mr. Murray, in February, 1858, had one of his feet crushed by the caving in of a mass of frozen earth, and, as Dr. Willard Parker, the eminent surgeon of New York who was called in consultation, said: “Young man, your clean, temperate life will save you and prevent the loss of that foot.” The accident, however, caused a permanent lameness which necessitated the use of crutches for some time, and he was never able to walk without the aid of a strong cane. The larger part of his work on the farm was accomplished, thereafter, on horseback. Throughout his life he was an intense sufferer as a result of this accident, but bore his sufferings with admirable patience, and was always cheerful and uncomplaining.

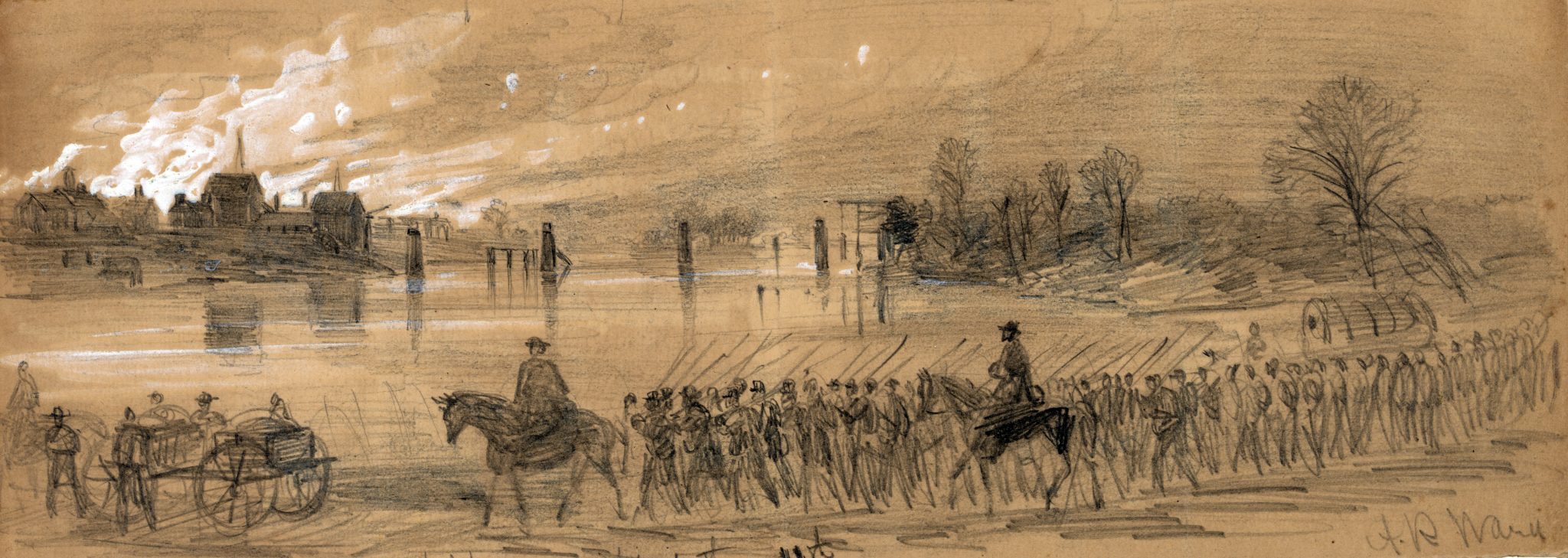

Mr. Murray was a keen observer of current events, and for some years prior to the outbreak of the Civil War he compiled several volumes of notes of speeches made by himself and others, having a bearing on the subject, and these are of great local interest to Monmouth county. He was frequently the orator of the day on public occasions, one of these, on which he delivered a particularly stirring and patriotic address, being May 26, 1861, when the people of Middletown erected a huge flagpole and raised a handsome flag. At the celebration, July 4, 1861, Mr. Murray made an eloquent and impassioned speech in favor of an undivided Union. On numerous other occasions he was equally convincing and patriotic.

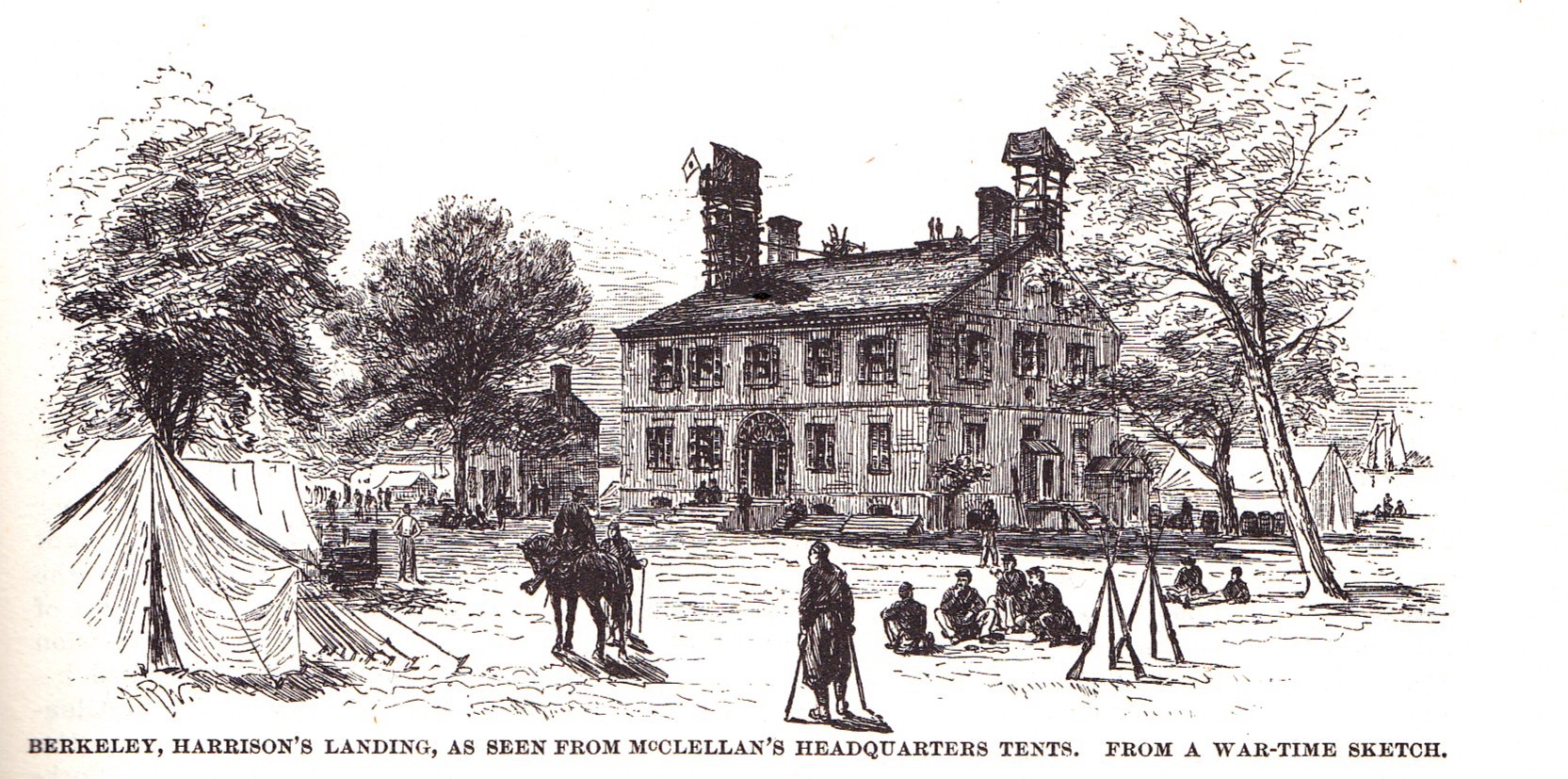

While a strong supporter of Democratic principles, Mr. Murray never allowed himself to be bound by party ties, but had the courage of his convictions, and did not hesitate to voice them, even at the expense of personal disadvantage. He was elected to the Legislature of New Jersey in the fall of 1861 and took an active part in the sessions. He served as a member of the committee on education, and the committee on the State Library. During this session the railroad companies were active in their efforts to obtain legislation which should be to their advantage, and in pursuance of this idea many fine dinners were given, to which Mr. Murray was also invited. After repeated and constant refusals on his part he was notified that if he did not come of his own accord, he would be compelled to attend by means of force. His reply was “that he would not accept the invitation; that he would be in his room at the appointed hour, but he wished to inform them that the first man who attempted to lay his hands upon him would do so at his own peril.” He remained unmolested until the close of the term of office. While he was debarred from active service in the army or navy by reason of his lameness, Mr. Murray was nevertheless an active worker in the cause of the Union. By means of public addresses, by public debate, in which he never lost his self control, his influence was wide spread and a beneficial one.

When the severity of the Draft Act of 1863 fell upon the poor men of his community, mostly upon the poor fishermen and the naturalized Irishmen, they appealed to him, their friend, for aid, knowing well that if there was help for them it would be found. In February, 1864, he obtained the endorsement of several prominent men of the town, and was thus enabled to draw a large sum of money from the Middletown Bank to be used for the purchase of substitutes for the poor men of the town who had been drafted, and whose families would be threatened with starvation were the only provider for the family taken from them. Mr. Murray strapped this “bounty money” securely about his body and set out for Washington, February 27, 1864. During this trip of nearly two weeks he was almost afraid to snatch a few moments for much needed rest, owing to the desperate character of men who followed him constantly, in the hope of securing this money. In spite of all his efforts, Mr. Murray was not able to secure the exemption of all the men for whom he pleaded, and upon his return to his home he made immense sacrifices in his endeavor to support the families who were left destitute. A large share of his crops was bestowed in charity of this nature, and upon him was bestowed the well earned and well deserved title of the “Poor man’s friend.” As a judge of election after the war, Mr. Murray accepted those voters who were eligible according to the laws then in force. This was against the ideas of some of the politicians and he was advised to leave his home, as his enemies would have him indicted for accepting illegal votes. He answered: “I will be right here on my place. If there is a grand jury in Monmouth county that will indict me for doing my duty, I am willing to stand my trial.” And he remained at home until notified that the grand jury had refused to listen to the complaint against him.

During his absence in Washington he had been elected assessor for the township of Middletown, an office he filled with ability for a number of years. When land became valuable along the Shrewsbury river for summer residences, Mr. Murray with his usual interest in behalf of the poorer classes, found that the small owners were bearing the larger share of the taxation, and he determined to rectify this matter. This resulted, as might have been foreseen, in the making of many enemies among the richer owners, but this did not deter Mr. Murray from carrying out his intention, which he did successfully.

Upon the death of his father in 1865, Mr. Murray succeeded him as trustee of the Middletown Baptist Church, being the third generation in a direct line to hold this office, and in 1872, he was elected clerk of the board of trustees. In order to carry out the provisions of the will of his father, Mr. Murray was obliged to mortgage the farm, and his fortune was further decreased by the development of farming interests in the south and west. He abandoned conservative farming as being unproductive of pecuniary results, and commenced raising products easy of culture and requiring the least amount of labor. In many instances he supplanted the labor of human hands by machinery of his own invention, and during the period of ten years following the Civil War he made many experiments along the lines of increasing the commercial value of the products of his farm. A number of the experiments which he then made have since that time been taken into practical use, and have been productive of excellent results. He was neither extravagant nor a speculator, but in the scope of his work he was too far in advance of the times. He foresaw the fact that New Jersey would become a residential and commercial State rather than an agricultural one, but the time was not ripe for the successful carrying out of his ideas. When Monmouth county suffered heavy losses by the embezzlement of some tax collectors, Mr. Murray was active in the prosecution of George W. Patterson and Alvan B. Hallenbeck, tax collectors of Freehold and Middletown townships. In this matter he was acting deliberately against his private interests, as he was one of the bondsmen of Mr. Hallenbeck, but it was one of his fixed principles to place the public welfare above his private affairs, no matter at what cost to himself. Few believed that he was honest in his conduct of this matter, but he was upheld by the courage of his convictions. Having sustained other losses about the same time, Mr. Murray was unable to pay off the mortgage on his farm, and this was foreclosed in 1880. Bereft of all but his household goods, he again bravely took up the struggle for an existence, handicapped as he was of lameness and approaching old age. This struggle, brave as it was, lasted but a few years,

as he died on Thanksgiving Day, 1884.

Mr. Murray married, February 27, 1855, Mary Catherine Cooper, born Mary 20, 1833, a daughter of James and Rebecca (Patterson) Cooper; granddaughter of George and Abigail (Oakley) Cooper, of Westchester county, New York…”

I could find no images of Lavinia; the woodcut depiction of a young woman standing on the outskirts of Middleton, New Jersey, in the 1830s is purely conjectural.

Index to Journal Entries

1834-1835 Entries are published below.

1836-1837-1838-1839 Entries

1840-1841-1842 Entries

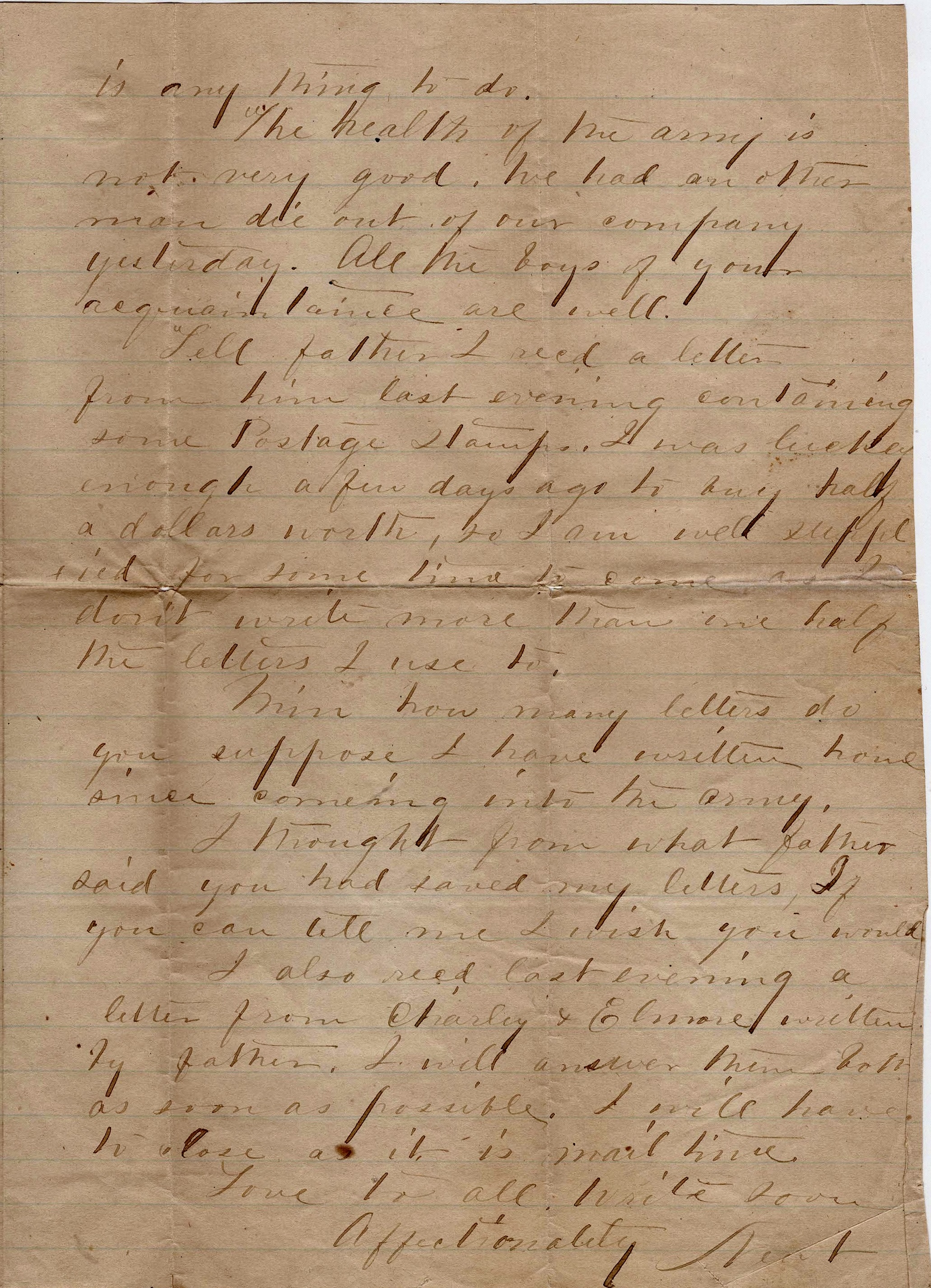

1834 May, Private Journal, Middletown, N. J.

What woman has done, woman may do.

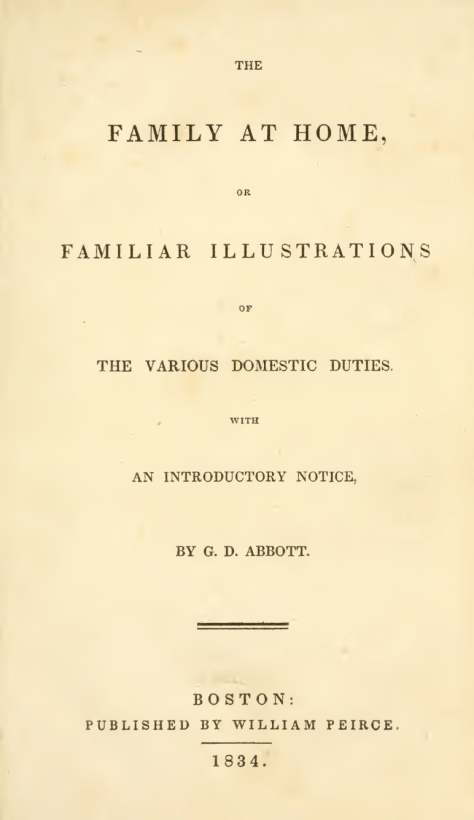

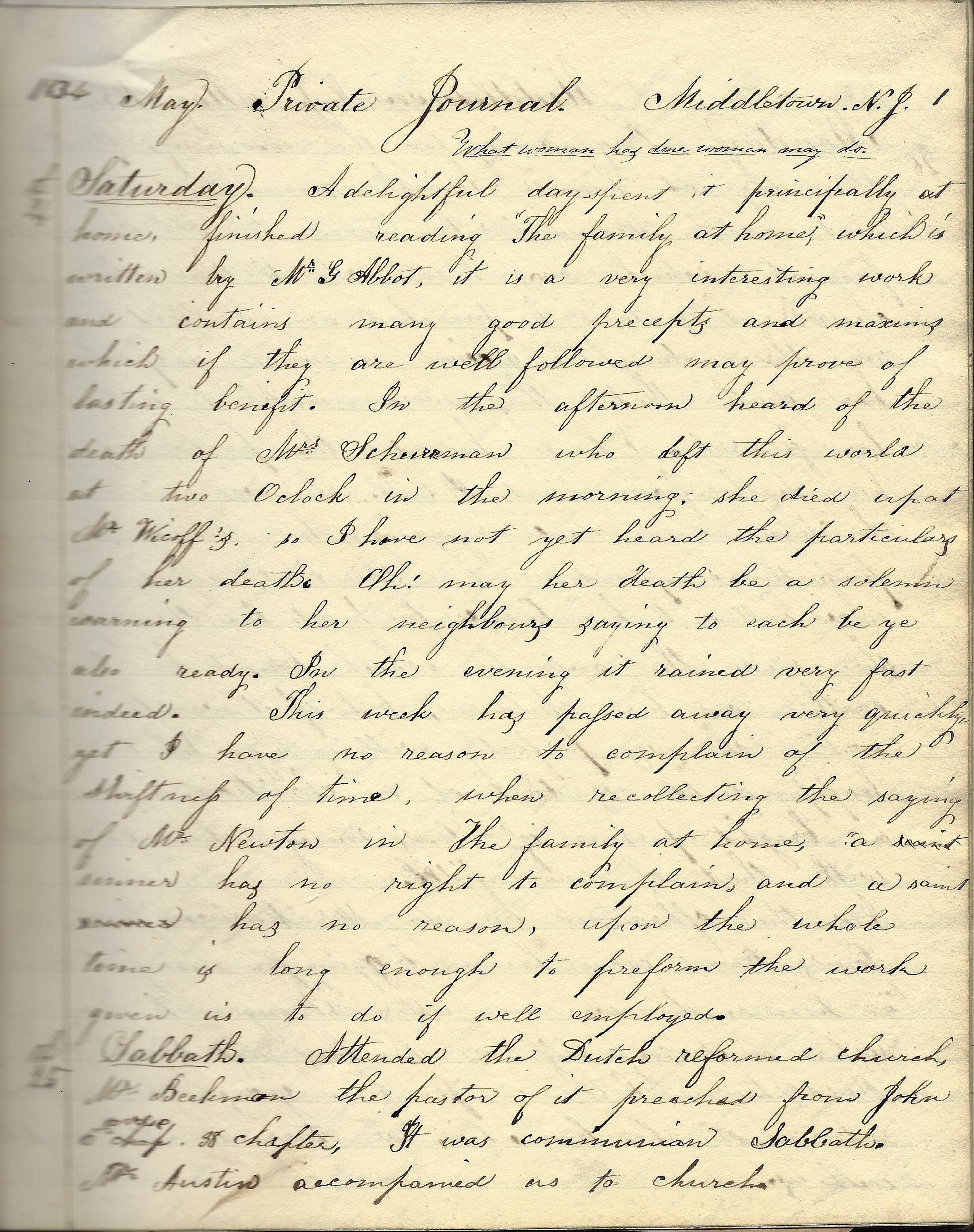

24th Saturday. A delightful day. Spent it principally at home. Finished reading “The Family at Home” which is written by Mr. G[orham D.] Abbott. It is a very interesting work and contains many good precepts and maxims which if they are well followed may prove of lasting benefit. In the afternoon heard of the death of Mrs. [Julia Anne Conover] Schureman who left this world at two o’clock in the morning. She died up at Mr. [Nathaniel S.] Wyckoff’s [in Freehold, N. J.] so I have not yet heard the particulars of her death. Oh! may her death be a solemn warning to her neighbors saying to each be ye also ready. In the evening it rained very fast indeed. This week has passed away very quickly yet I have no reason to complain of the shriftness of time, when recollecting the saying of Mr. [Mr. John] Newton in The Family at Home, “A sinner has no right to complain and a saint has no reason.” Upon the whole, time is long enough to perform the work given us to do if well employed.

25th Sabbath. Attended the Dutch Reformed Church. Mr. Beekman, the pastor of it preached from John, 6th Verse, 38th Chapter. It was communion Sabbath. Mr. Austin accompanied us to church.

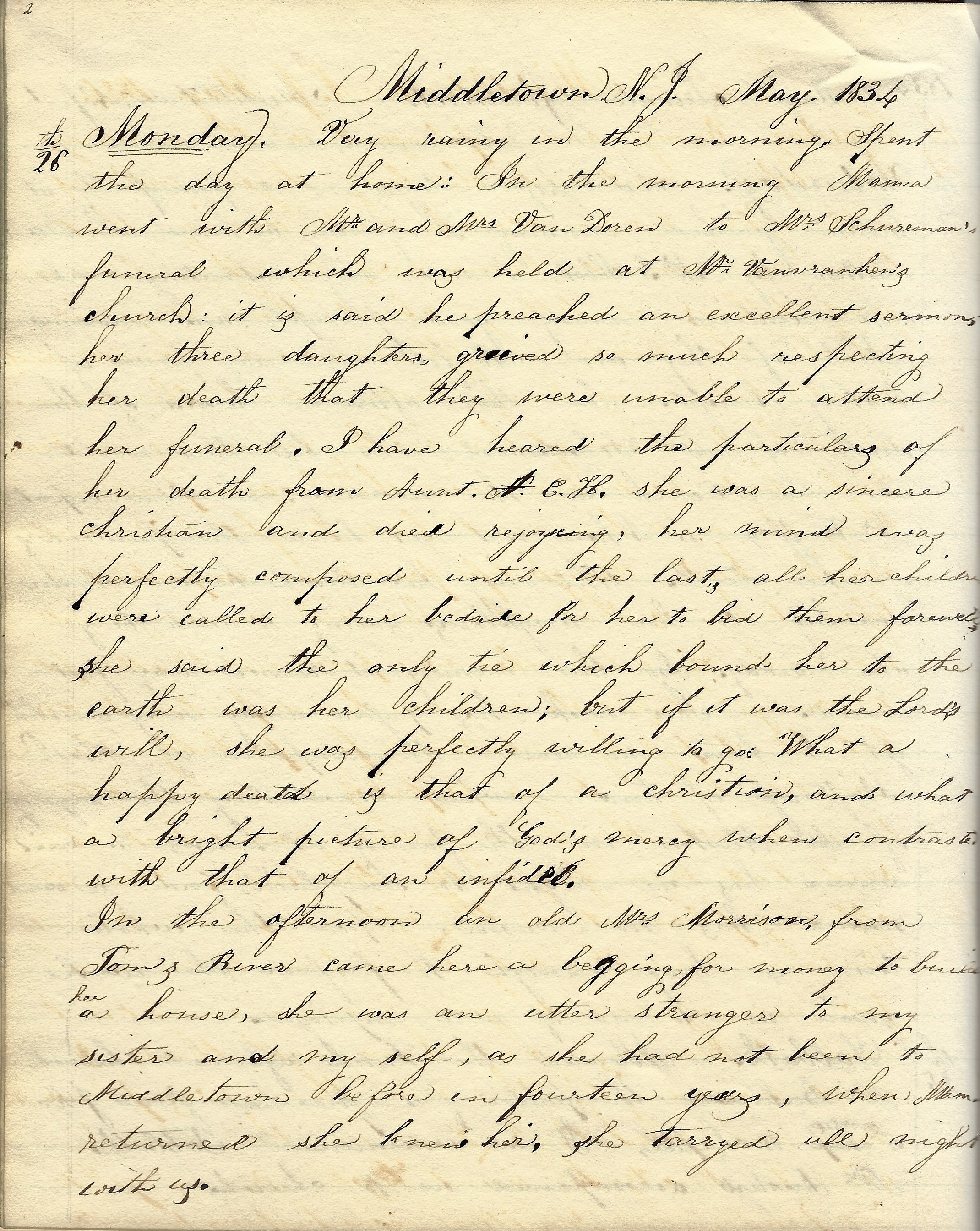

Middletown, N. J. May 26, 1845, Monday. Very rainy in the morning. Spent the day at home. In the morning, Mama went with Mr. and Mrs. Van Doren to Mrs. Schureman’s funeral which was held at Mr. Vanvranken’s church. It is said he preached an excellent sermon. Her three daughters grieved so much respecting her death that they were unable to attend her funeral. I have heard the particulars of her death from Aunt A. C. H. She was a sincere christian and died rejoicing, her mind was perfectly composed until the last. All her children were called to her bedside for her to bid them farewell. She said the only tie which bound her to the earth was her children, but if it was the Lord’s will, she was perfectly willing to go. What a happy death is that of a christian, and what a bright picture of God’s mercy when contrasted with that of an infidel.

In the afternoon an old Mrs. Morrison from Tom’s River came here a begging for money to build her a house. She was an utter stranger to my sister and myself as she had not been to Middletown before in fourteen years, When Mama returned, she knew her. She tarried all night with us.

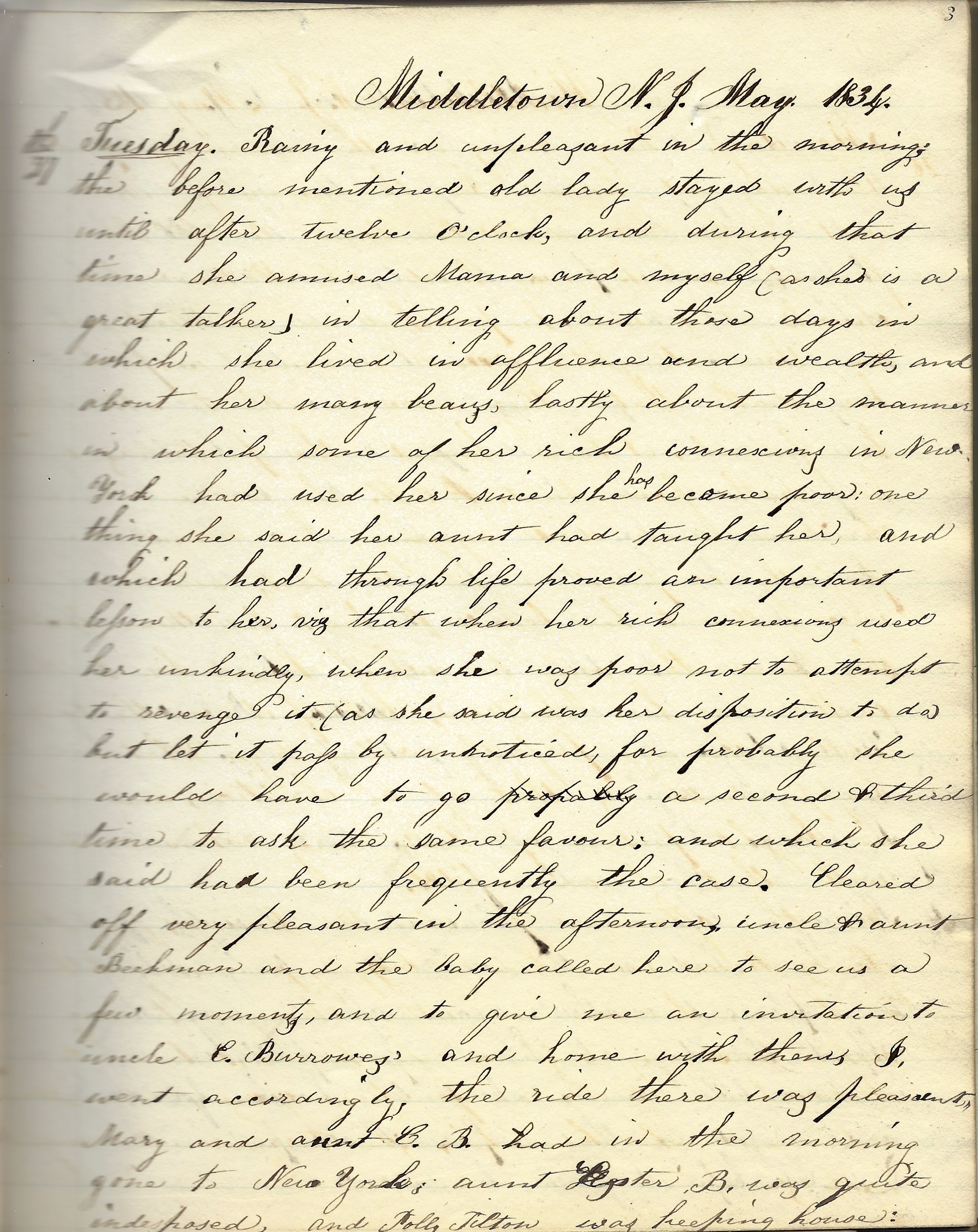

Middletown, N. J. May 27, 1834, Tuesday. Rainy and unpleasant in the morning. The before mentioned lady stayed with us until after twelve o’clock and during that time she amused Mama and myself (as she’s a great talker) in telling about those days in which she lived in affluence and wealth, and about her many beaus. Lastly about the manner is which some of her rich connections in New York had used her since she became poor. One thing she said her aunt had taught her, and which had through life proved and important lesson to her—viz. that when her rich connections used her unkindly when she was poor, not to attempt revenge. It (as she said was her disposition to do), but let it pass unnoticed, for probably she would have to go a second or third time to ask the same favor, and which she said had been frequently the case. Cleared off very pleasant in the afternoon. Uncle and aunt Beekman and the baby called here to see us a few moments and to give me an invitation to Uncle C. Burrowes’ and home with them. I went accordingly. The ride there was pleasant. Mary and aunt E. B. had in the morning gone to New York; aunt Ester B. was quite indisposed and Pollo Tilton was keeping house. We stayed there only a few moments and returned to Grand papa’s where I spent the afternoon. Aunt A. E. H. was there also. Grandpapa’s health is no better. Had a pleasant visit and returned home with aunt A. E. H. Shecalled sometime at our house.

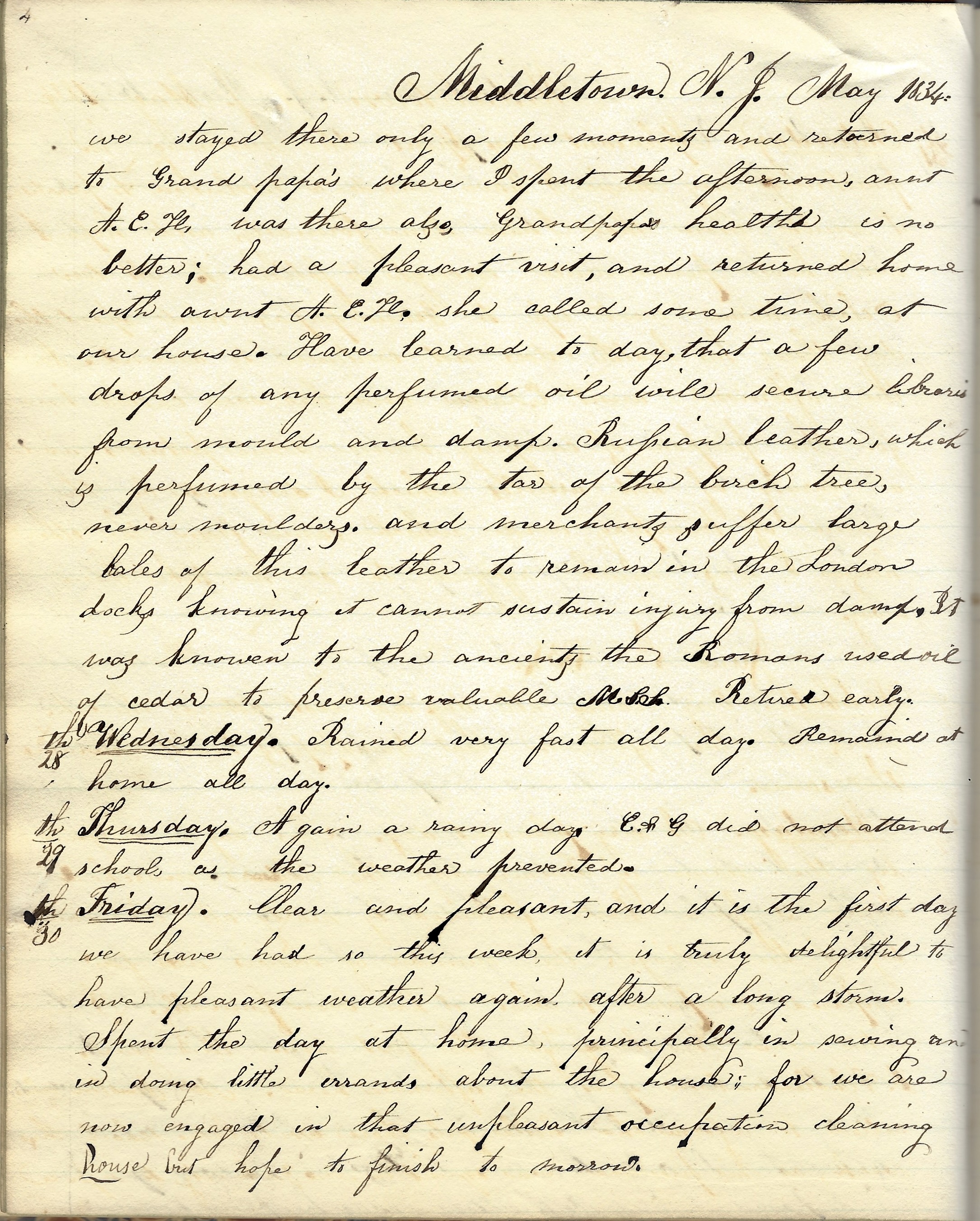

Have learned today that a few drops of any perfumed oil will secure [ ] from mould and damp. Russian leather, which is perfumed by the tar of the birch tree, never moulders, and merchants suffer large bales of this leather to remain in the London docks knowing it cannot sustain injury from damp. It was known to the ancients the Romans used oil of cedar to preserve valuable M. C. L. Retured early.

Wednesday 28th. Rained very fast all day. Remained at home all day.

Thursday 29th. Again a rainy day. E & G. [Eleanor & George] did not attend school as the weather prevented.

Friday 30th. Clear and pleasant, and it is the first day we have had so this week. It is truly delightful to have pleasant weather again after a long storm. Spent the day at home, principally in sewing and doing little errands about the house for we are now engaged in that unpleasant occupation cleaning house, but hope to finish tomorrow.

Middletown, N. J. May 31, 1834, Saturday. A pleasant day. Spent the morning in practicing my music. I have made a resolution to practice it much more that I have done formerly and hope I will have perseverance enough to follow it. At ten o’clock, Mama went up to Grand Papa’s and spent the day there. His health does not continue to amend. In the afternoon, Aunt E. Laten and her son called here for the purpose of carrying home some potatoes and a variety of old articles which I designate by the name of trumpery and which came from the other house, I was much rejoiced to see her take them away.

Sabbath, June 1st 1834. Very rainy all day. Did not attend church. Heard in the afternoon that grandpapa’s health remains the same.

Monday 2nd. A very pleasant day. This day is designated by the name of Training Day. The soldiers marched down as far as here followed by nearly all the small boys of the village. The number of soldiers were few compared to what it has been formally. I have eaten some strawberries for the first time this year. E. P. A. Hendrickson spent the afternoon here. Mr. Austin also called to inform the little girls there would be no school this week as his presence was requisite in New York City to sign a paper respecting his expected fortune which is coming from England. Walked nearly home with E. & A.H. Retired early.

Tuesday 3rd. A warm and pleasant day. The weather now really beginning to feel like summer. Mrs. [Rachel Bowne] Winter who died on Sabbath last was buried today.

Wednesday 4th. Received in the afternoon calls from Uncle Timothy and Aunt H. White, Catharine, Morford, and Aunt A. C. Hendrickson. Just at evening there fell a delightful shower of rain.

Thursday 5th. Rainy all day.

Friday 6th. Spent the morning in reading. Uncle Beekman and Miss C. D. spent the afternoon here.

Saturday 7th. Very warm. Have read today a description of Mr. Wort’s [?] death written in two long letters by his third daughter. They were very beautifully written. Mr. Austin who has returned from New York spent part of the afternoon here.

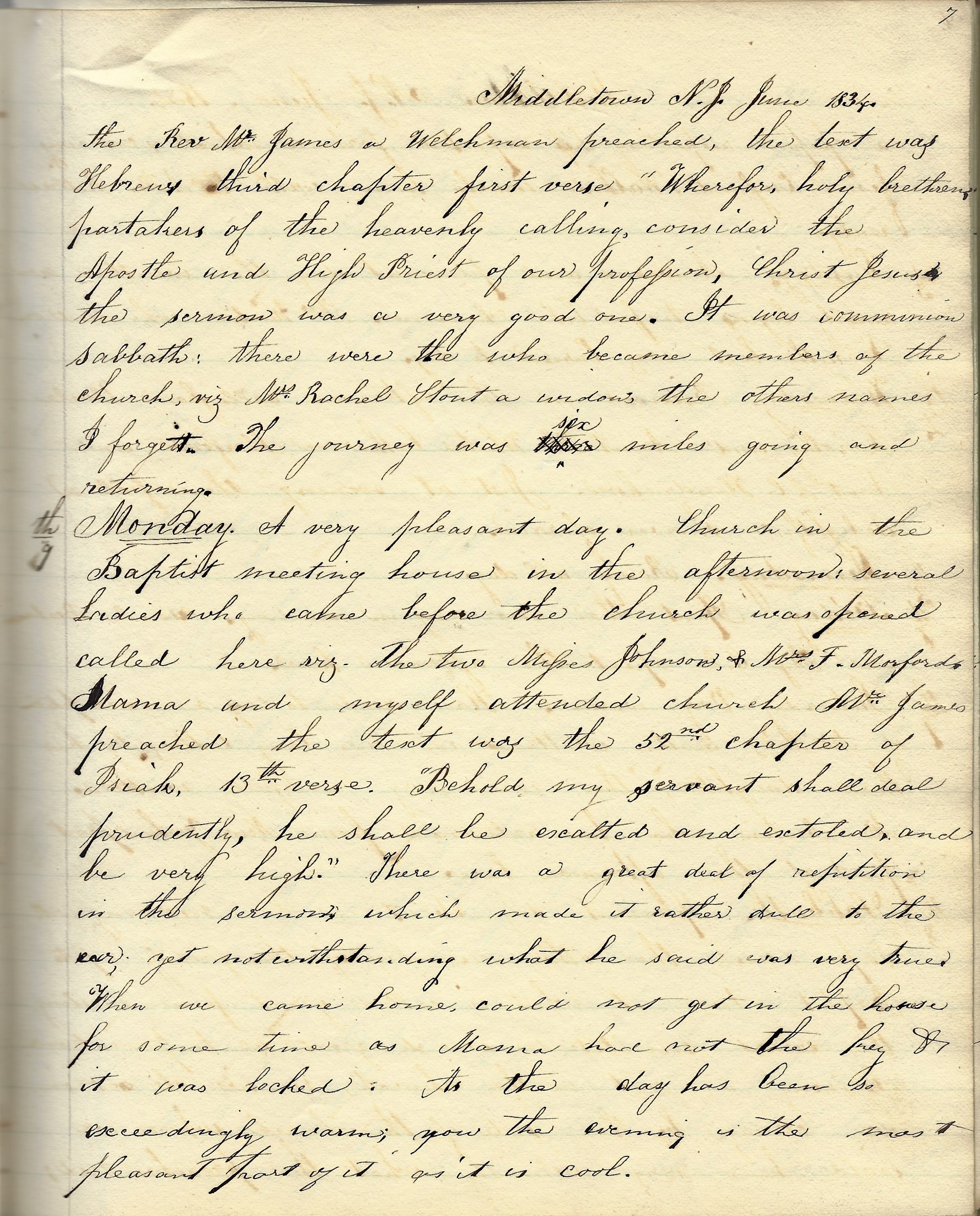

Sabbath 8th. A pleasant day. Went in the morning with Papa and the other members of the family up to Baptisttown [Later called Holmdel Village] to what is called Great June Meeting. The multitude was so great as to prevent our obtaining a seat in the church [the Upper Meeting House of the Baptist Church], so we all sat in our carriage by the side of the church where we could hear very distinctly what the preacher said. The Rev. Mr. James, a Welshman, preached. The text was Hebrews, third chapter, first verse. “Wherefore, holy brethren, partakers of the heavenly calling, consider the Apostle and High Priest of our profession, Christ Jesus. The sermon was a very good one. It was communion Sabbath: there were three who became members of the church, viz—Rachel Stout, a widow; the others’ names I forget. The journey was six miles going and returning.

Monday 9th. A very pleasant day. Church in the Baptist Meeting House in the afternoon. Several ladies who came before the church was opened called here, viz—the two Miss Johnsons and Mrs. F. Morford. Mama and myself attended church. Mr. James preached. The text was the 52nd Chapter of Isiah, 13th Verse. “Behold my servant shall deal prudently. He shall be exalted and extolled, and be very high.” There was a great deal of repetition in the sermon which made it rather dull to the ear, yet notwithstanding what he said was very true. When we came home, could not get in the house for some time as Mama had not the key & it was locked. As the day has been so exceedingly warm, you [know] the evening is the most pleasant part of it as it is cool.

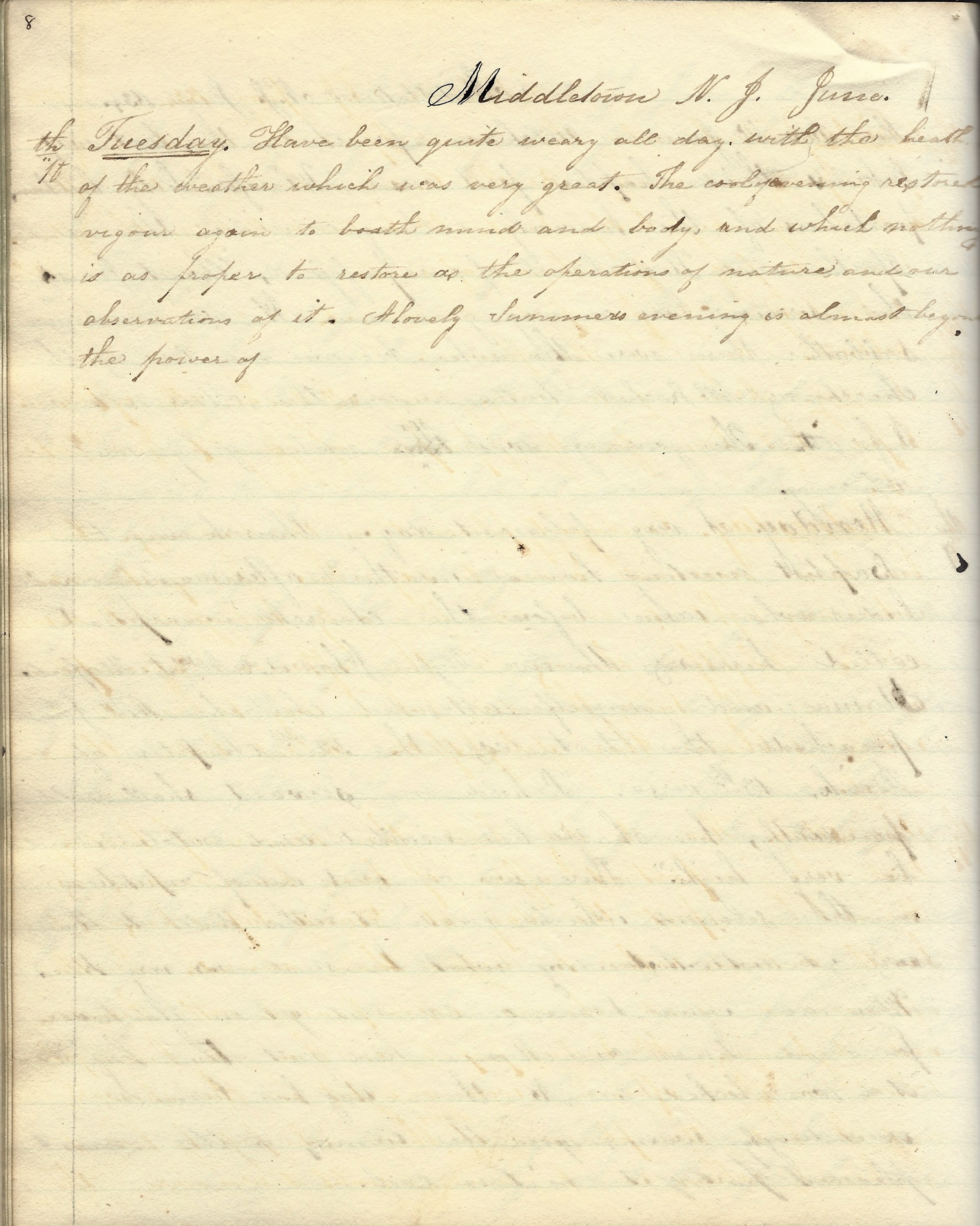

Tuesday 10th. Have been quite weary all day with the heat of the weather which was very great. The cool of evening restored vigor again to boost mind and body, and which nothing is as proper to restore as the operation of nature and our observations of it. A lovely summer’s evening is almost beyond the power of [unfinished thought; remainder of page blank]

Friday 13th. Much cooler than usual. Spent the day at home principally in sewing. Brother George came home in the afternoon with his eye very badly hurt. Mr. Austin called in the afternoon. There also fell a fine shower of rain.

Saturday 14th. Nothing particular occurred.

Sabbath 15th. Rainy in the afternoon.

Tuesday 17th. Arose quite early, Rainy all day. In the afternoon, Papa left home for the purpose of going to New York City.

Wednesday 18th. Exceedingly pleasant in the morning. The bees have swarmed again today. This was quite an interesting sight to me who had only witnessed it once before. Delightful showers in the afternoon accompanied by unusually heavy thunder which may be called rather sublime than delightful. Retired later than usual.

Thursday 19th. Have today had the honor of holding that very important office of being housekeeper as Mama has spent the day at Grand Papa’s house. His health continues rather to decline than amend. In the afternoon as usual, showers accompanied with thunder and lightning. Mr. Austin’s pupils on their way home from school in the afternoon were caught in the shower and I had the pleasure of having those who pass by hereto go home, calling in to remain until it was over. The following is the names of those who called—viz. E. A. & G. Hendrickson, M. and D. Willet, C. Truex who is Mr. Austin’s assistant in teaching the young idea how to shoot, and Edgar Henrickson. I was quite amused with their conversation. I have learnt that a bee hive should be rubbed with cream and sugar, or with molasses, salt, & peach tree leaves before the bees are put in it.

Friday 20th. As usual, showers accompanied with thunder and lightning. the bees swarmed again which makes four swarms we have had from the hive that came from the other house. In the afternoon papa returned home from New York. Learnt the melancholy news of the death of the illustrious General Lafayette, which news was received at the city on yesterday. He died at a quarter of five o’clock on the morning of May 20th 1834. The venerable general was born September 1st 1757 and was nearly 77 years old when he died. In him America loses an early, faithful, and disinterested friend and champion of her independence, and her children may well weep for a great man is departed.

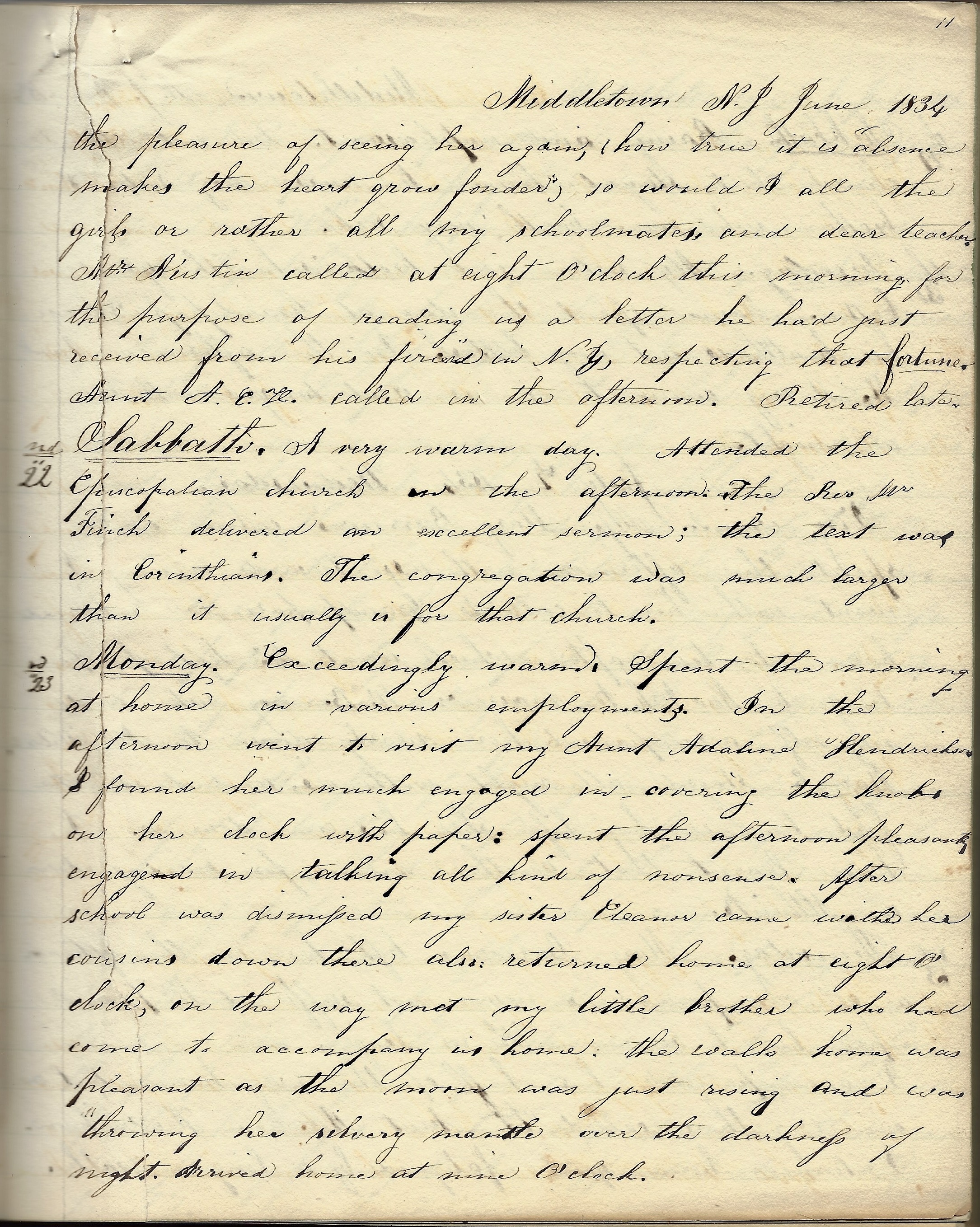

Saturday 21st. The first perfectly clear day we have had this week. Papa had his new articles carted up from the sloop. To mu great joy he brought me a note from my dear friend Amelia. She enjoys very good health. I would like very much to have the pleasure of seeing her again. How true it is—“absence makes the heart grow fonder.” So would I all the girls, or rather all my schoolmates and dear teachers. Mr. Austin called at eight o’clock this morning for the purpose of reading us a letter he had just received from his friend in New York respecting that fortune. Aunt A. E. H. called in the afternoon. Retired late.

Sabbath 22nd. A very warm day. Attended the Episcopalian church in the afternoon. The Rev. Mr. Finch delivered an excellent sermon. The text was in Corinthians. The congregation was much larger than it usually is for that church.

Monday 23rd. Exceedingly warm. Spent the morning at home in various employments. In the afternoon went to visit my Aunt Adaline Hendrickson. I found her much engaged in covering the knobs on her clock with paper. Spent the afternoon pleasantly engaged in talking all kind of nonsense. After school was dismissed, my sister Eleanor came with her cousins down there also. Returned home at eight o’clock. On the way met my little brother [George] who had come to accompany us home. The walk home was pleasant as the moon was just rising and was “throwing her silvery mantle over the darkness of night. Arrived home at nine o’clock.

Sabbath 29th. Rainy and unpleasant. Did not attend church but stayed home to nurse my sister and brother who were both very sick.

Tuesday 31st. My sister and brother’s health grew better. Mama spent the day at Grandpapa’s house. His health is not any better. In the afternoon Aunt M. Murray came to see us and tarried with us all night.

Wednesday, July 2nd 1834. Very warm. Miss Mary Burrowes came and spent the afternoon with us. Towards evening I went with her to call to Grandpapa’s. We returned home to tea, after which Aunt M. left purposing to go to New York tomorrow. Mary Burrowes, my sister, and myself accompanied her nearly down to Mr. Willet’s. Mary B. stayed all night with us and it is the first time in her life she has ever done so. I have learnt that another name for Roses of Sharon is Althea.

Thursday 3rd. Mary Burrowes left here in the afternoon as all our persuasions were not sufficient to prevail upon her to remain with us longer. I accompanied her half of the way home, but on our way there called upon Aunt Adaline Hendrickson. I returned home quite fatigued by so long a walk.

Friday 4th [of July 1834]. I am again permitted to see this great day on which 58 years past our forefathers declared themselves independent. What happy emotions rise in our breasts by taking a retrospective view of such a noble action, and also by keeping this day in remembrance of the fourth of July 1776. In the afternoon attended a Temperance Meeting held at the Baptist church. It was a meeting of the different societies meet together, which belong to our township of Middletown. There was an address delivered by J. Patterson, Esq., Rev. Mr Woodhull, and Mr. Goble. The latter was from Chesapeakes. He delivered a very good address. It was proposed by our pastor, the Rev. Mr. [Thomas] Roberts [pastor of the Lower Congregation Baptist Church in Middletown, N. J.], that every person belonging to the society would endeavor to induce one person at least to join between this and the first of January next, and bring an account of it to the Temperance Meeting which is held on that day. I think this is an very good proposition and hope every member will use their utmost influence in complying with it. It was also proposed there would be another meeting held on the 3rd Tuesday in August for the purpose of forming out of the different societies of the townships, a township society. There are 446 persons belonging to the different societies of the township. I hope the Temperance cause will continue to succeed.

Saturday 12th. Attended the funeral of my dear Grandfather who immortal soul left its earthly habitation on yesterday to land, we hope, on that fair shore where tempests never beat, nor billows roar. During his last sickness his bodily sufferings were very excruciating, but they were ended by death. Oh! what a destroying Angel he is, but we ought all to feel the “Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away. Blessed be His name.” Our dear departed had been a resident with us eighty years and we feel it is hard—very hard, to part. But may we from it take warning and be ready. The Rev. Mr. Roberts preached from Job, “If I am wicked, woe unto me. If I am righteous, I shall not hold up my head.”

Wednesday 17th [16th]. Received an account by our New York paper of a dreadful riot occasioned by a mob who have risen in that city to put down the doctrine of amalgamation which is supported by the Rev. Dr. [Samuel Hanson] Cox, Rev. Mr. [Henry Gilbert] Ludlow, the Tappans [Arthur & Lewis Tappan] and others. The two first mentioned persons have had their churches demolished by the mob and have been obliged to leave the city. They have also demolished many of the African churches. The idea of a mob is dreadful yet I think they act from right motives. It is hoped the above mentioned opinions will soon be abolished in our country.

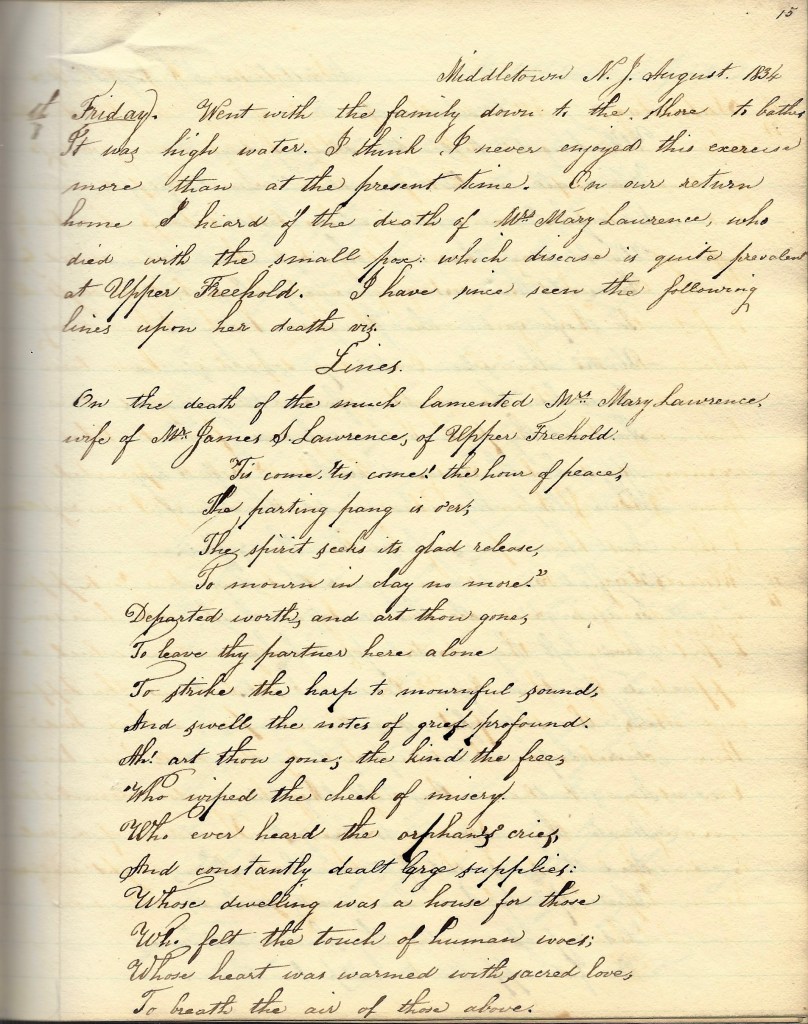

Middletown, N. J. August 8, 1834, Friday. Went with the family down to the shore to bathe. It was high water. I think I never enjoyed this exercise more than at the present time. On our return home, I heard of the death of Mrs. Mary Lawrence who died with the small pox which disease is quite prevalent at Upper Freehold. I have seen the following lines upon her death—viz:

Lines. On the death of the much lamented Mrs. Mary Lawrence, wife of James S. Lawrence of Upper Freehold.

These lines [in poem above] portray nothing but Mrs. Lawrence’s true character.

Middletown, New Jersey, August 19, 1834, Wednesday. Pleasant. I attended the funeral of Uncle and Aunt Beckman’s only child, Edwin. He died yesterday evening with the summer complaint [dysentery]. The Rev. Mr. Woodhull, a Dutch Reformed minister preached the funeral sermon. Text was in Genesis. His opinion was that infants when they leave this world go to a happy one. His Mother was so much grieved as to faint upon account of his death. It was the wise will of the Lord to call him from tis terrestrial world before he had tasted its pleasures or been seduced by its vices; and it is our duty to say, “Thy will be done.” I heard in the evening that Mrs. Eusebia Tilbons’ child was brought over on Monday from New York to Middletown and buried here.

Monday 24th. Saw an authentic account in the newspaper of the burning of the Ursuline Convent, Mount Benedict, Charlestown [Massachusetts], a Catholic Institution, by a mob and the [fire] engines when called out refused to help stop the flames. Their reason for burning it was they thought a young lady was confined there but it was not the case. The young lady had voluntarily taken the veil and her friends were permitted to call when they wishes. Her name was Miss Elizabeth Harrison, and she was a music teacher. She has a brother residing in the city. There were forty-six young ladies at the nunnery at the time of its demolition. Many of them owned much valuable property which was stolen at the time of the conflagration which took place the 15th of August [actually 11 & 12, 1834].

Friday, September 5, 1834. Rainy, as this week has been principally, and which we received from the clouds with thankful hearts, as before it came we had quite a drouth, but which did not do much damage here as in the upper part of the state. The cholera has again visited our country and the number of deaths today in New York were 24. It rages now in Detroit and Buffalo, but has ceased to in Montreal.

Sabbath 7th. Very warm but clear. Attended the Baptist church. Heard a very good sermon delivered by the Rev. Mr. Roberts. The text was, “Awake, wake; put on the strength, O Zion; put on thy beautiful garments, O Jerusalem, the holy city; for henceforth there shall no more come unto the uncircumscribed and unclean.” The subject of discourse was how much good a Christian could do and ought to do, for the world, and those who complain they have no talents, if they would only employ what they have for the good of their fellow men, do their duty and sometimes do astonishingly. In the afternoon had several showers.

Wednesday 10th. In the afternoon Mama and myself visited at Mr. Van Doren’s. The family was at home and well. Miss Lydia Stillwell was there also. The afternoon was spent in laughing and chatting, neither of which contributed to instruction or improvement in knowledge. Old Mrs. Van Doren continues well, but I think has grown more childish than when I last saw her.

Thursday 11th. Nothing of importance has occurred.

Friday 12th. So very cold. I should presume we were in the winter solstice, if I had lost my senses. I went in the afternoon to spend a week with my grandmother to entertain her as well as I know, as Aunt and Uncle B[eckman] with whom she resides. Left today for New Brunswick and intend spending a week at her Father-in-laws who resides north of New Brunswick. I expect to spend the week very happily.

13th, 14th, 15th. All passed away pleasantly. As we two are the only human beings in the house, we appear lonesome, but in reality are not so as my grandmother related to me incidents of her early life which to me are new and interesting, and it also give her pleasure to review them. I have spent some time in reading in Buck’s Theological Dictionary. The meaning of the wold “Catholic” is universal or general. Ruth, the colored woman, is recovering her health.

Tuesday 16th. Was called home to see Uncle James and Aunt A. Murray from Staton Island. Was very happy to see them. Returned to Grandmother’s in the afternoon.

Friday 19th. Rainy all day at intervals. I went with Sarah Ann Hendrickson and her brother to spend the day at cousin Th. Conover’s. I was there introduced to Miss R. McFarquor and Miss Castle, from my short acquaintance with both. I am most pleased with the last. I returned in the evening just before Aunt and Uncle B[eckman]. They were much fatigued with traveling; consequently we all retired early.

Saturday 20th. Returned home very early this morning to prepare for going to Trenton with Papa and Mama. The former is called there upon business, and we go for curiosity and visiting. Left home at ten o’clock in the morning. Reached Hightstown, our place of destination until Monday, in the evening after riding 30 miles and being much fatigued. We took our dinner at English town which is half way between home and Hightstown. We also passed through Millford. The country presented a very level appearance and also appeared fertile. Found Mr. Ely’s family well. They reside three miles from Heights town. Spent the evening in talking until eleven o’clock when I retired.

Sunday 21st. Attended church at Hightstown. Rev. Mr. Seers preached from these words. “In whom we have boldness and access with confidence by the faith of Him.” Ephesians 3rd Chapter, 12 verse.

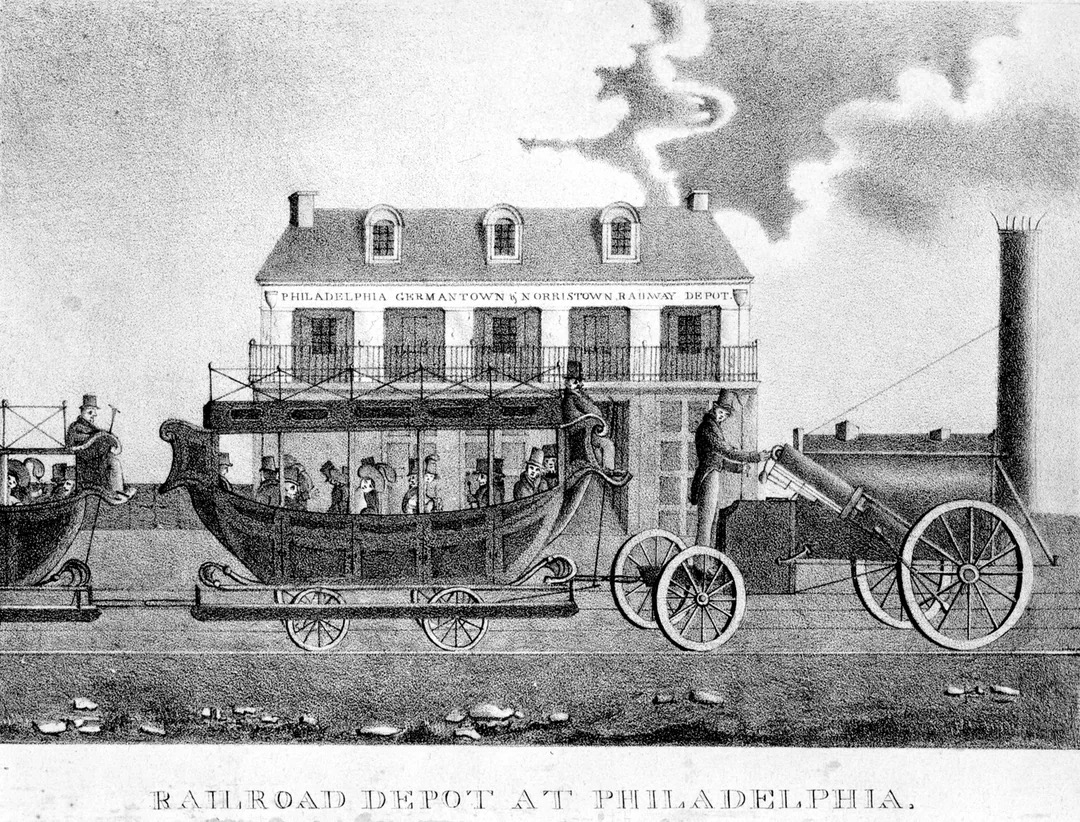

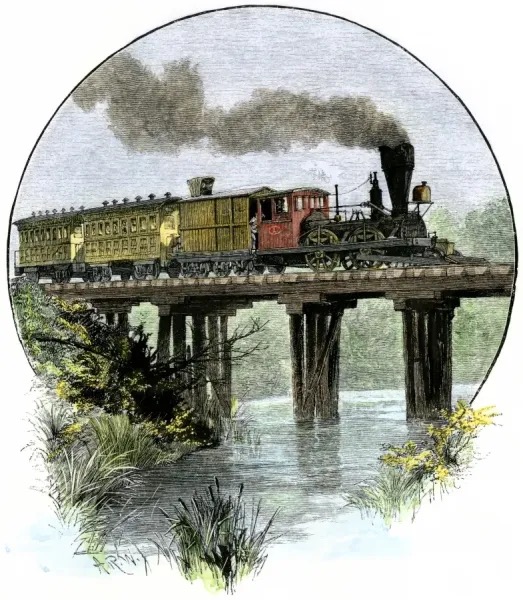

Monday 22nd. We left Hightstown in the morning accompanied by Mr. Ely’s for Trenton. The morning was very pleasant. Arrived at Trenton at nine o’clock in the morning after twelve mile ride. During our journey I had a beautiful view of the railroad which extends from Amboy to Philadelphia. This I think is truly a great invention. I had also a beautiful view of the [Delaware and Raritan] canal which we passed over just previous to entering Trenton.

Trenton is not a large city but very pleasantly situated. The principal public buildings are the State House and State Prison. The former is built oddly stone and quite large. the interior did not look very neat. The rooms that I was in were furnished according to the purpose for which they were used with desks, chairs, and a chair much higher and of mahogany for the Governor. There was also framed and hung up in the Assembly room Washington’s valedictory address to the People of the United States and the Declaration of Independence with the signers names. We were shown in the room where judgements were recorded and kept. It was not adjoining the State House. It was intended for fire proof being made with a brick floor. It contained some of the proceedings of parliament which was written during Queen Ann’s reign. The writing was very good and the paper appeared almost as well as new. I learn that during the King’s reign over America, each lawyer recorded their own judgements upon papers in the form of parchment rolls.

The State Prison was a large building of stone, white washed and enclosed with a large high yard. We first were shown in the work shops. In the first one the prisoners were wearing tablecloths, cloth carpets, &c. They were kept busily employed by a keeper who was with them constantly. In the shoemaker shop, many were employed making shoes. I soon saw none were allowed to be idle. The shops are upon one side of the yard and are not adjoining the prison. The prisoners had pointed hats on and shirts numbered in the breast with red. Their dining room is in the basement story. It contains two tables which reach from one end to the other. They are set out with small wooden tubs bound with iron hoops which the prisoners eat out of at intervals. A pail of water is placed. Their principal diet is mush made of yellow corn. It contains 120 prisoners, 7 of who are women. In the sick room or hospital were 7 or 8 indisposed.

The most interesting were those in solitary confinement of which there were four. One of them was a splendid writer and had written his name on the wall of his cell most beautifully which name was Philip Brockaway. He had also cut the whole name several times in German text with a pen knife on the wall which was also done elegantly. What a pity such talents should moulder in a prison. I requested him to write his name for me. This he did not do, but gave me a part of a letter which he had written, which contained nothing of importance. It is not written as well as he can write, owing to the weakening of his arms.

From the top of the prison I could see across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania, and also had a fine view of Trenton bridge. In the new prison which is building near this, every prisoner has a separate cell which will make it more solitary than this, where two prisoners sleep together except those in solitary confinement. Seeing the prisoners made such an impression on my mind, I will not attempt to describe it. Left Trenton at sunset and arrived at Mr. Ely’s at nine in the evening. Retired at 11 o’clock.

Tuesday 23rd. Left Mr. Ely’s at 9 o’clock in the morning for home. Traveling was not very pleasant as we rode through the rain three hours. At Englishtown, took our dinner and proceeded on our journey at three o’clock. Arrived at home in the evening. Found sister and brother well and also the other members of the family. Being much fatigued with my journey, retired early.

Wednesday 24th. Very pleasant. Spent the day at home in various employments.

Tuesday, October 21, 1834. This afternoon one of my schoolmates, Sarah Ann Hendrickson [1816-1843], is to be married to [Rev.] Mr. Garret [Conover] Schenck [1806-1888], a Dutch Domini. Uncle Beekman is to perform the ceremony. The number of the company invited is quite small. In the morning left home to visit New York City.

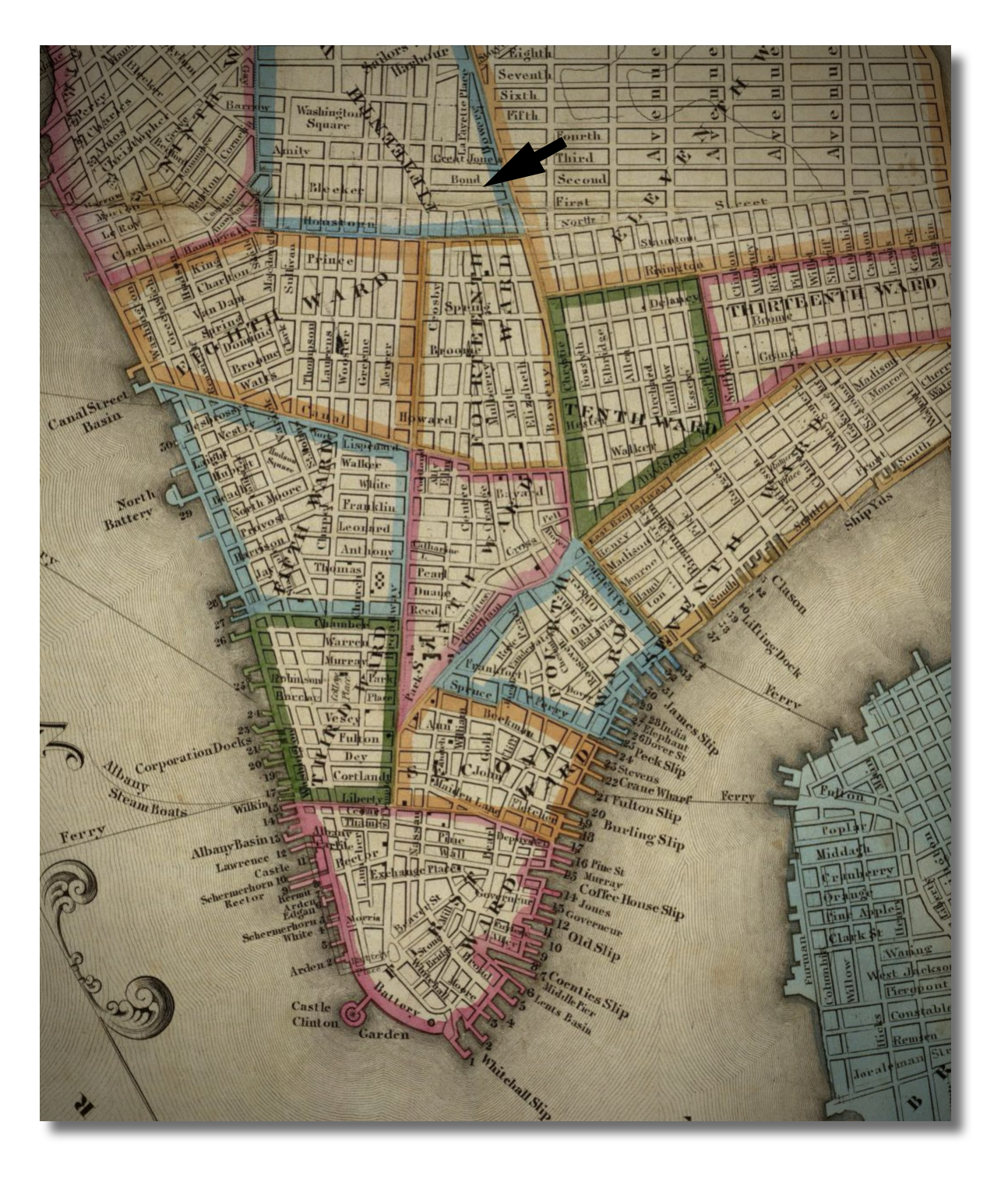

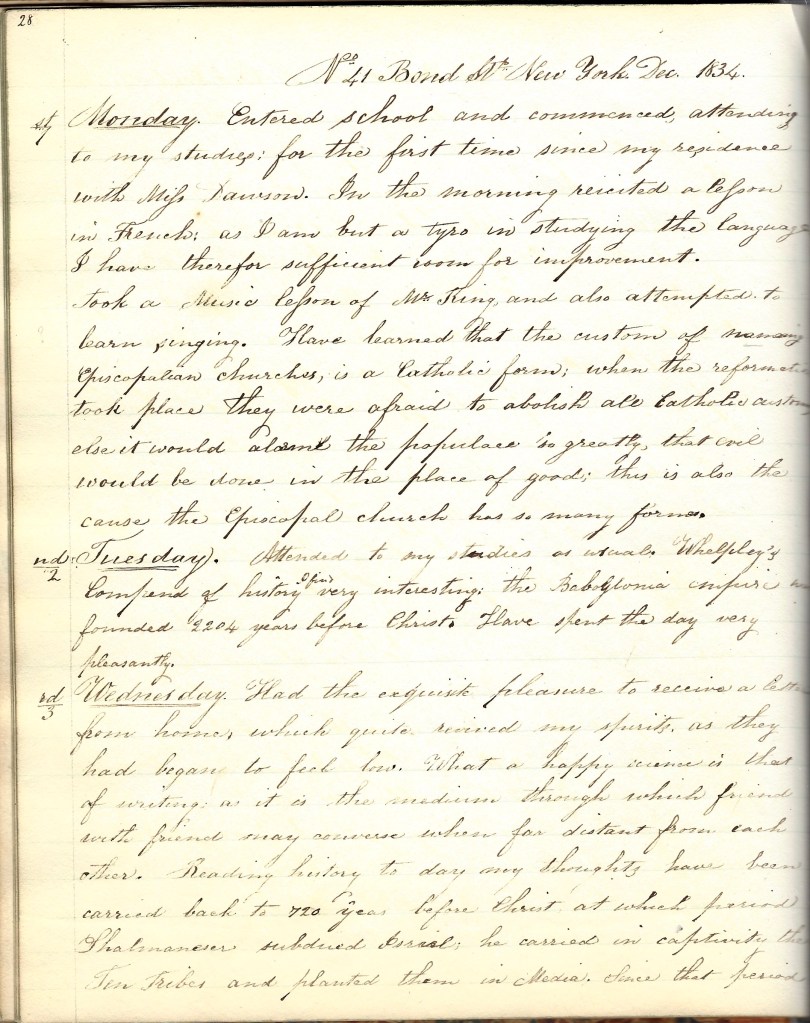

No. 41 Bond Street, New York [City]

November 27th 1834, Thursday. The sun shone delightfully upon our earth and distributed particles of much warmth upon us. In the morning I called upon Miss Julia Mallison, my wax teacher. I found her engaged as she almost constantly is with wax making flowers. She received this year the gold medal at the American Institute for superiority in wax work. Left my friends in the afternoon in company with Papa for Miss Dawson’s School. Papa left me in a short time after we arrived there to return home. Spent the evening in practicing my music and in conversation with Miss Dawson and her sister. I feel quite in love with them. They are so kind and pleasant. I think I shall be happy during my residence here.

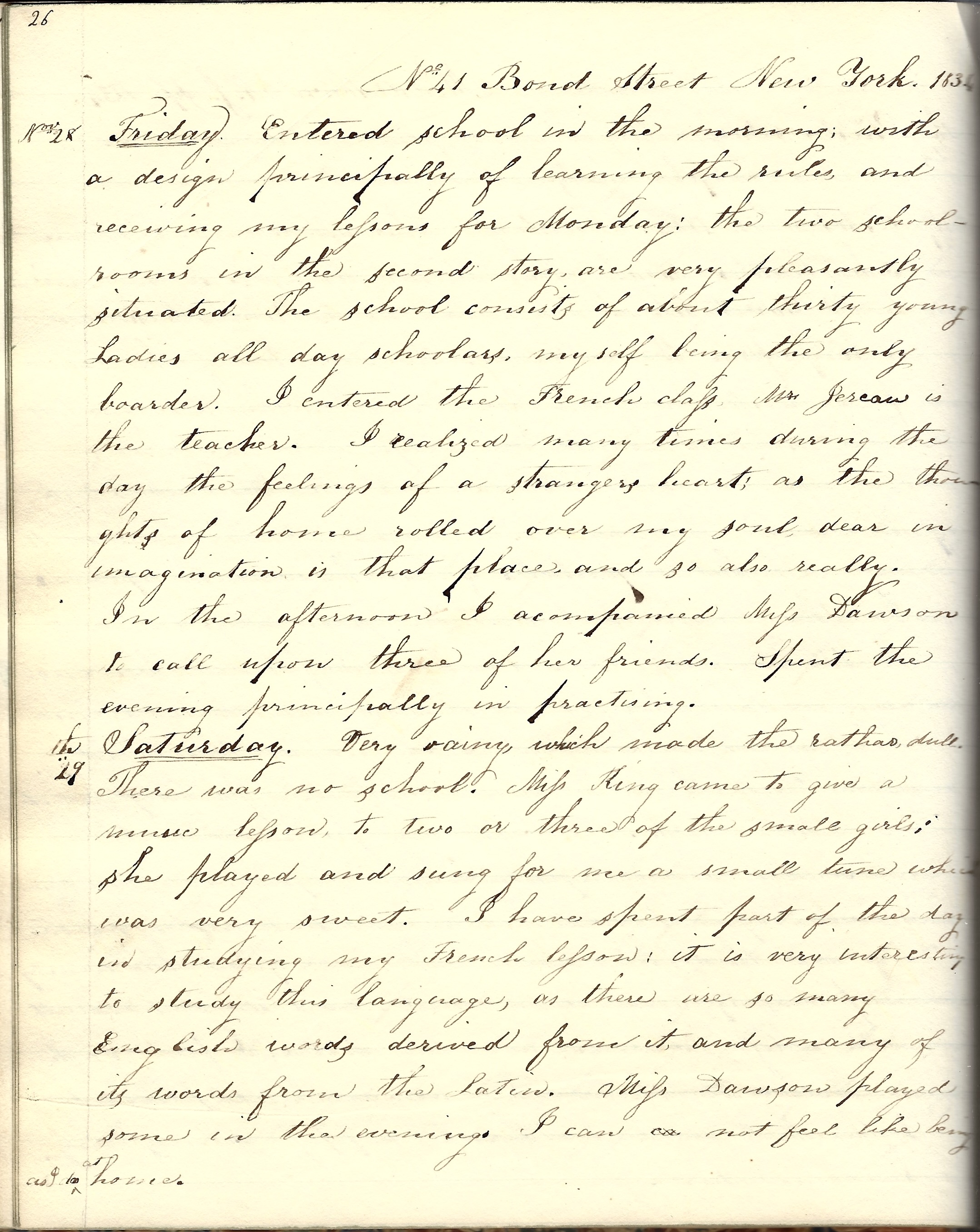

Friday 28th. Entered school in the morning with a design principally of learning the rules and receiving my lessons for Monday. The two schoolrooms in the second story are very pleasantly situated. The school consists of about thirty young ladies—all day scholars; myself being the only boarder. I entered the French class. Mr. Jereau is the teacher. I realized many times during the day the feelings of a stranger’s heart as the thoughts of home rolled over my soul. Dear in imagination is that place and so also really. In the afternoon I accompanied Miss Dawson to call upon three of her friends. Spent the evening principally in practicing.

Saturday 29th. Very rainy which made the day rather dull. There was no school. Miss King came to give a music lesson to two or three of the small girls. She played and sung for me a small tune which was very sweet. I have spent part of the day in studying this language, as there are so many English words from the Latin. Miss Dawson played some in the evening. I cannot feel like being as I do at home.

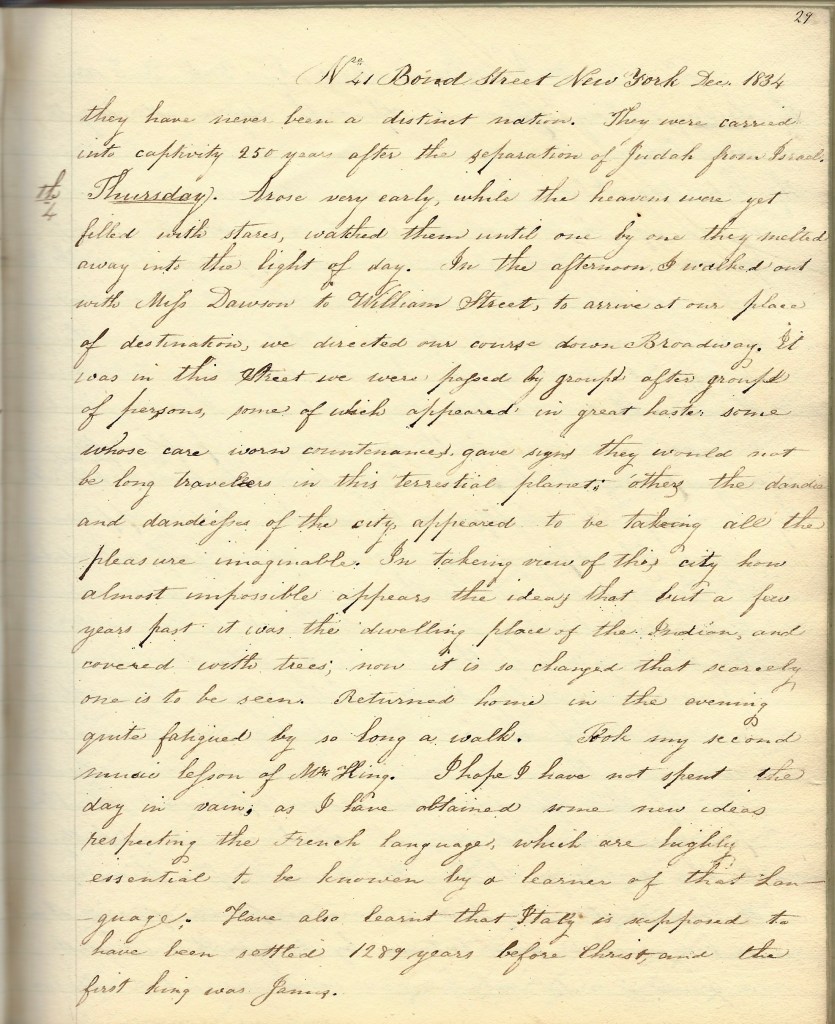

Sunday, November 30th. Pleasant. In the morning, Miss Dawson and myself attended the Episcopal Church in a hotel in Broadway. A stranger preached. The text was, “It is a true saying and worthy of all acception that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners.” At six minutes after 1 o’clock, the great Eclipse of the Sun commenced. The greatest obscuration was at 29 minutes after two o’clock. It ended 47 minutes after three o’clock. This was a sight worthy of attention from its singularity and more so, as we will not again have the moon’s shadow fall on any part of the United States for thirty-five years. I will then, perhaps, be sleeping in the chambers of the dust, and those who are with me at the present day—viz: Miss E. H. Dawson, M. Dawson, and Mr. Dawson. The sun was totally eclipsed at Charleston, S. C., at Augusta, Georgia, and at Tuscaloosa two minutes.

In the afternoon, attended with Miss Dawson St. Clements Church. The Rev. Mr. Biard preached from these words, “There is no respect of persons with God.” It was an excellent sermon. Spent the evening in learning a Bible lesson in Second Samuel. It gave an account of Uzza’s death & showed with what awe we should deal with sacred things. It also contained mush of the history of David. Retired to rest at nine o’clock.

Monday, December 1st. Entered school and commenced attending to my studies for the first time since my residence with Miss Dawson. In the morning, recited a lesson in French as I am but a tyro in studying the language. I have therefore sufficient room for improvement. Took a music lesson of Mr. King and also attempted to learn singing. Have learned that the custom of naming Episcopalian churches is a Catholic form. When the reformation took place, they were afraid to abolish all Catholic customs else it would alarm the populace so greatly that evil would be done in the place of good. This is also the cause the Episcopal church has so many forms.

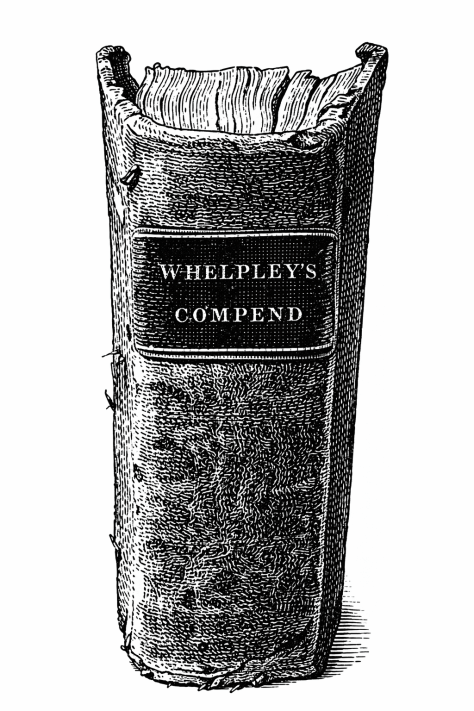

Tuesday 2nd. Attended to my studies as usual. [Samuel] Whelpley’s Compend of History I find very interesting. The Babylonia empire was founded 2204 years before Christ. Have spent the day very pleasantly.

Wednesday 3rd. Had the exquisite pleasure to receive a letter from home which quite revived my spirits as they had began to feel low. What a happy science is that of writing as it is the medium through which friend with friend may converse when far distant from each other. Reading history today my thoughts have been carried back to 720 years before Christ at which period [the Assyrian King] Shalmaneser subdued Israel. He carried in captivity the ten tribes and planted them in Media. Since that period they have never been a distant nation. They were carried into captivity 250 years after the separation of Judah from Israel.

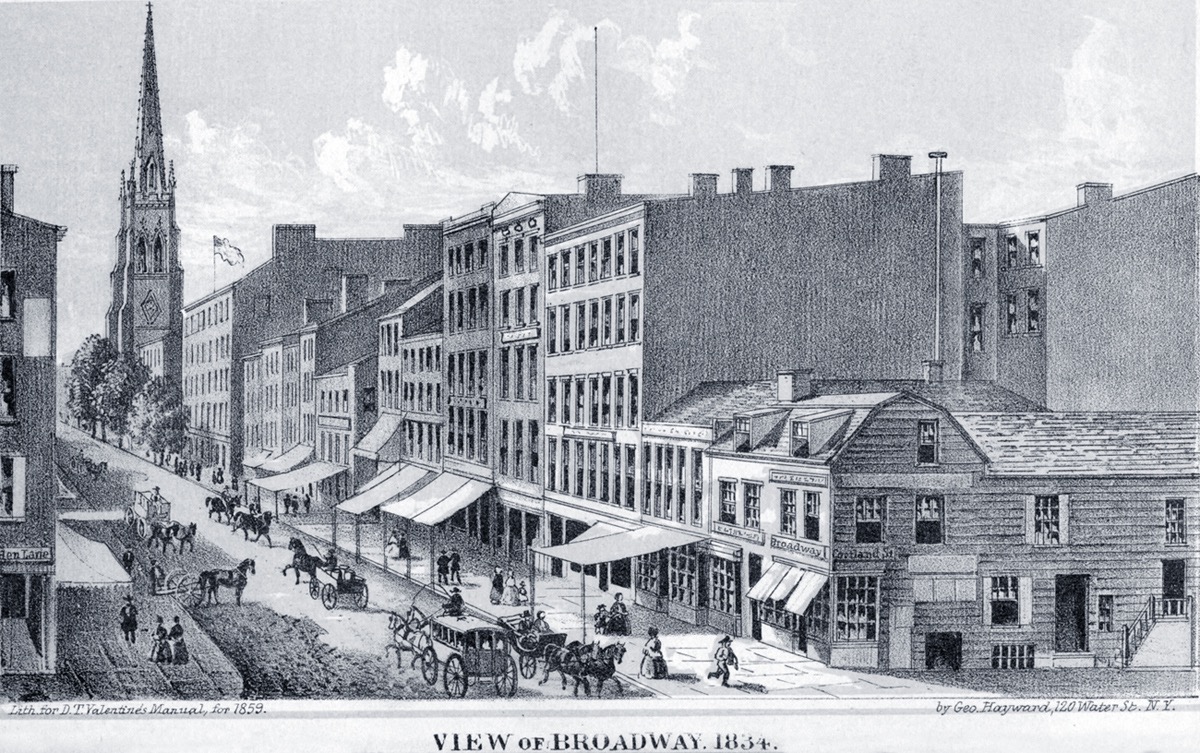

Thursday 4th. Arose very early while the heavens were yet filled with stars. Watched them until one by one they melted away into the light of day. In the afternoon I walked out with Miss Dawson to William Street. To arrive at our destination, we directed our course down Broadway. It was in this street we were passed by group after group of persons, some of which appeared in great haste, some whose careworn countenances gave signs they would not be long travelers in this terrestrial planet; others—the dandies and dandiesses of the city—seemed to be taking all the pleasure imaginable. In taking view of this city, how almost impossible appears the ideas that but a few years past it was the dwelling place of the Indian and covered with trees. Now it is so changed that scarcely one is to be seen. Returned home in the evening quite fatigued by so long a walk.

Took my second music lesson of Mr. King. I hope I have not spent this day in vain as I have obtained some new ideas respecting the French language which are highly essential to be known by a learner of that language. Have also learnt that Italy is supposed to have been settled 1289 years before Christ and the first king was Janus.

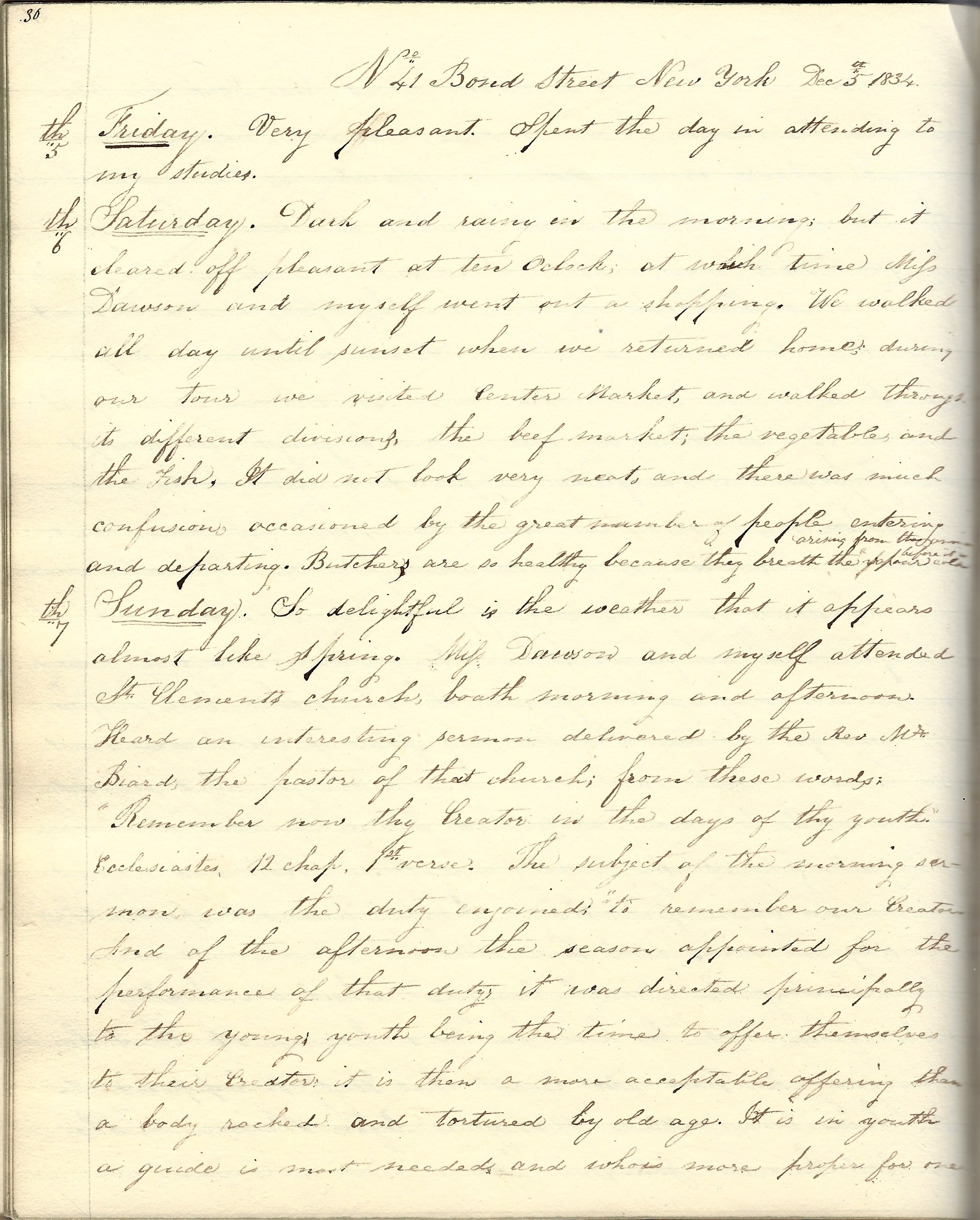

Friday, December 5, 1834. Very pleasant. Spent the day in attending to my studies.

Saturday 6th. Dark and rainy in the morning but it cleared off pleasant at ten o’clock at which time Miss Dawson and myself went out a shopping. We walked all day until sunset when we returned home. During our tour we visited Center Market and walked through the different divisions—the beef market, the vegetable, and the fish. It did not look very neat and there was much confusion occasioned by the great number of people entering and departing. Butchers are so healthy because the vapor arising from the [ ] before it is cold.

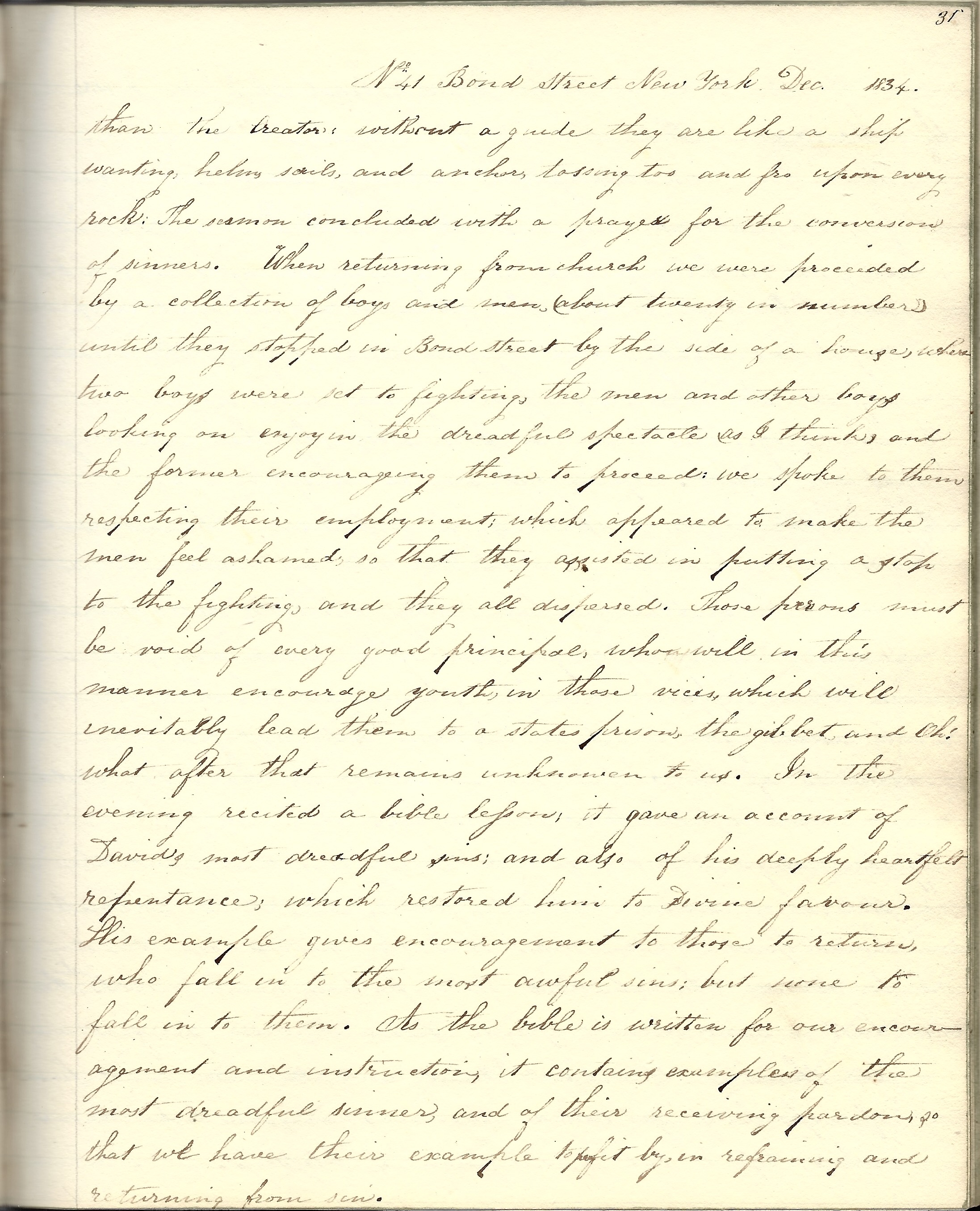

Sunday 7th. So delightful is the weather that it appears almost like Spring. Miss Dawson and myself attended St. Clement’s [Episcopal] church [108 Amity Street], both morning and afternoon. Heard an interesting sermon delivered by the Rev. Mr. Biard, the pastor of the church, from these words, “Remember now the Creator in the days of thy youth.” Ecclesiastics, 12th Chapter, 1st Verse. The subject of the morning sermon was the duty enjoined to remember our Creator and of the afternoon the season appointed for the performance of that duty. It was directed principally to the young; youth being the time to offer themselves to their Creator. It is then a more acceptable offering than a body racked and tortured by old age. It is in youth a guide is most needed and who is more proper for one than the Creator. Without a guide they are like a ship wanting helm, sails, and anchor, tossing to and fro upon every rock. The sermon concluded with a prayer for the conversion of sinners.

When returning from church, we were preceded by a collection of boys and men (about twenty in number) until they stopped in Bond Street by the side of a house where two boys were set to fighting, the men and other boys looking on enjoying the dreadful spectacle (as I think) and the former encouraging them to proceed. We spoke to them respecting their employment which appeared to make the men feel ashamed so that they assisted in putting a stop to the fighting and they all dispersed. Those persons must be void of every good principle who will in this manner encourage youth in those vices which will inevitably lead them to a state prison, the gibbet and Oh! what after that remains unknown to us.

In the evening recited a bible lesson. It gave an account of David’s most dreadful sins and also of his deeply heartfelt repentance which restored him to Divine favor. His example gives encouragement to those to return who fall into the most awful sins, but none to fall into them. As the bible is written for our encouragement and instruction, it contains examples of the most dreadful sinner, and of their receiving pardon so that we have their example to profit by in refraining and returning from sin.

Monday 8th. Pleasant and quite warm for the season. Have been much engaged with my studies but do not feel satisfied with my days labor as I have not been diligent in business fervent in spirit serving the Lord “but may I be led to see the manner in which to improve my time rightly and rejoice to perform the same. Spent the evening in practicing my music.

Tuesday 9th. Was aroused from sleep by the wanderings of my mind. Spent the day in study.

Wednesday 10th. Nothing of importance has occurred during school times. In the evening when the moon had thrown her silvery mantle over our earth, I had a beautiful prospect of a chimney on fire in a street opposite this. The flame and smoke continued to ascend for an hour, the one rolling up from the mouth of the chimney in dark clouds; the other casting light upon all adjacent objects.

Thursday 11th. A day of general thanksgiving throughout the state, so of course a holiday for us. It is the third one I have spent in New York. It is the custom on this day to attend church and have feasting and mirth as though the latter can never spring from a more perfect source than a thankful heart and this we must have if a spark of gratitude remains unquenched as our whole life is but a succession of blessings.

Friday 12th. Spent the day with Miss Dawson and was employed part of the time in writing a letter home.

Saturday 13th. Remained at home engaged in study and in practicing. I cannot feel contented as I have not received a letter from home in so long time.

Sabbath 14th. Attended Mr. Biard’s church in the morning. As I cannot remember the text, cannot relate much of the sermon. Returning from church Miss Dawson and I became nearly frozen—the weather is so tres tres cold. Did not attend church in the afternoon. Have learnt that the word Sheol or Hell means place of the departed and the word Hell when used to signify place of the damned, conveys an improper meaning of the original word which is derived from the Saxon word helan to cover. Recited a bible lesson in the evening.

Monday 15th. The cold is so great that the thermometer at eleven o’clock stood six degrees below the freezing point. Have learnt from Geology that the greatest excavations of earth only extend perpendicularly half a mile. The primitive rock is found always at the bottom of the greatest excavations and at the tops of the highest mountains—a fact which shows the wisdom of the Creator. Spent the evening in studying my lessons for the coming day.

Tuesday, December 16, 1834. Much warmer of which fact I was much pleased. The first lesson I recited was history which was interesting. It contained an account of the distinguished persons who lived from the period 752 years before Christ to the Battle of Marathon 490 years before Christ. The distinguished characters who lived during the period were Romulus who was the founder of the city of Roma. Aesop, a theologian philosopher and fableist. He is supposed to have been ugly and deformed in his person. Thales the founder of Ionic Philosophy which was distinguished for deep and obtuse speculations. Solon, a legislator and wise man of Greece. Pythagoras, a Grecian philosopher. Also Sappho, a poetess who drowned herself, leaving by her conduct an example not to be followed by posterity. In the evening Miss Dawson and myself walked down Broadway as far as Lockwood’s Book Store where we purchased some articles and returned home.

Wednesday 17th. My sixteenth birthday. I am really lost in amazement when I consider that I haves pent 16 years on the earth and have done scarcely anything for the good of the world. I must profit by past experience and from henceforth commence a life of more activity and usefulness. The ground has been partially covered with snow which I think adds much cheerfulness to winter. In the afternoon, the post man brought me a letter from home which formed an important ingredient in my mixture of happiness.

Thursday 18th. My intellect has become quite expanded with the news & ideas I have received this day, some of which were that rocks are composed of the following few simple minerals—quartz, mica, feldspar, limestone, gypsum or plaster of Paris, slate, and hornblende. Countries are named from the different strata which constitutes their basis or which predominate there, either primary, transition, secondary, tertiary, diluvial, or alluvial. Monsieur Girard related to the class an anecdote of Franklin, who with a Mr. [Silas] Deane and [Arthur] Lee was sent to France upon State affairs during the American Revolution. Franklin, during his stay there. became much beloved and respected, and received many presents, one of which was a box presented by the ladies which had embroidered upon, Le digne Franklin, which means the worthy Franklin. When the other two saw it they were jealous and appeared angry. Franklin, observing it, said the box was for them all, but the French people did not know how to spell English words so had merely the initials correct. This was one example of the nobleness of Franklin’s character.

Friday 19th. Warm and pleasant. Spent the day in study &c. Nothing of importance has occurred today as far as my knowledge extends.

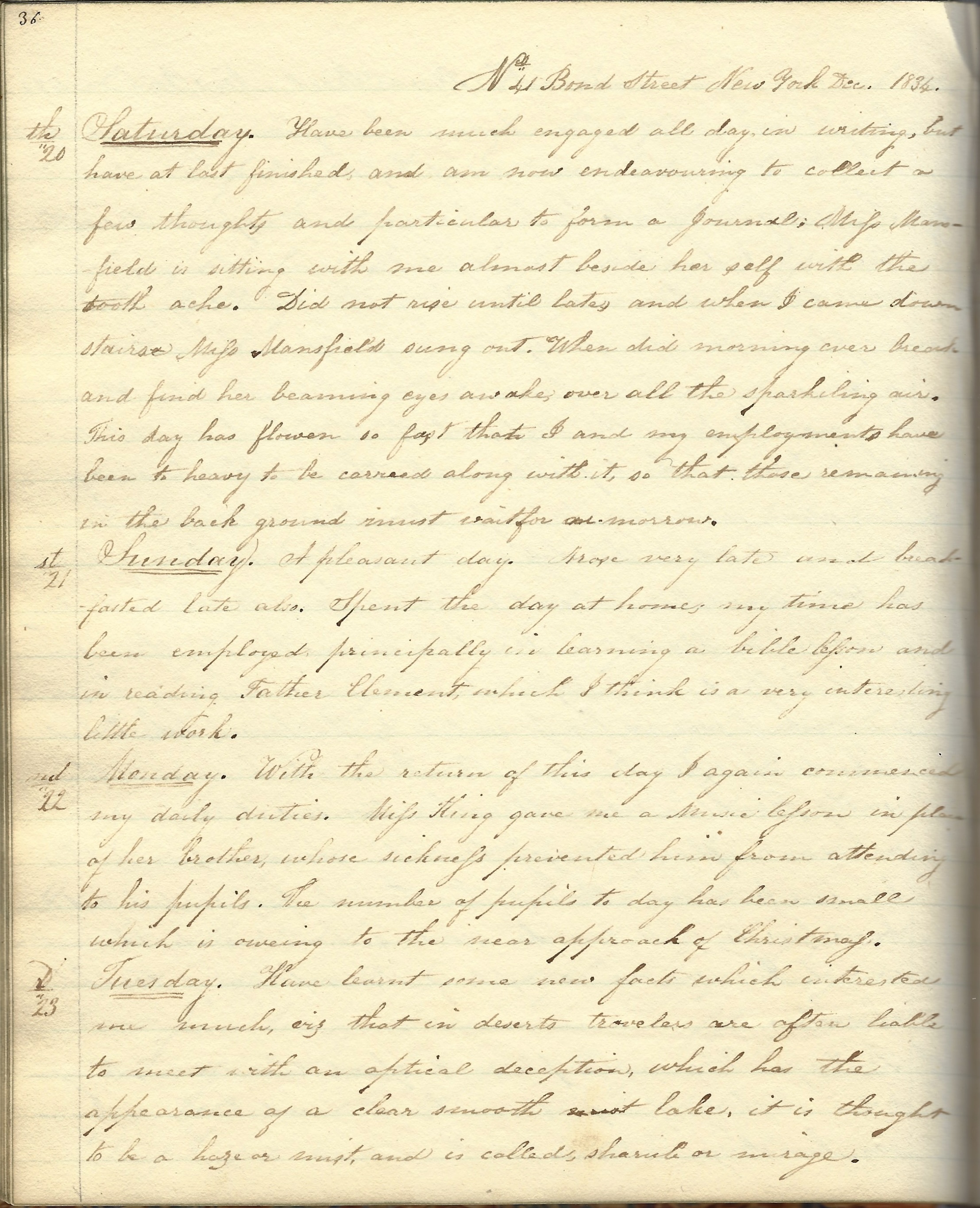

Saturday 20th. Have been much engaged all day in writing but have at last finished and am now endeavoring to collect a few thoughts and particular to form a journal. Miss Mansfield is sitting with me almost beside herself with the toothache. Did not rise until late and when I came downstairs, Miss Manfield sung out. When did morning ever break and find her beaming eyes awake over all the sparkling air. This day has flown so fast that I am my employments have been too heavy to be carried along with it so that those remaining in the background must wait for tomorrow.

Sunday 21st. A pleasant day. Arose very late and breakfasted late also. Spent the day at home. My time has been employed principally in learning a bible lesson and in reading Father Clement which I think is a very entertaining little work.

Monday 22nd. With the return of this day, I again commenced my daily duties. Miss King gave me a music lesson in place of her brother whose sickness prevented him from attending to his pupils. The number of pupils today has been small which is owing to the near approach of Christmas.

Tuesday 23rd. Have learnt some new facts which interested me much—viz, that in deserts, travelers are often liable to meet with an optical deception which has the appearance of a clear, smooth lake. It is thought to be a haze or mist and is called sharob or mirage.

Wednesday 24th. This afternoon commenced the Christmas holidays which was to continue until the first Monday after New Year’s day. I think I never saw the whole school taken collectively in better spirits.

Thursday 25th. Christmas. With pleasant weather is this day ushered in, although much like winter. In the morning it snowed until ten o’clock when it ceased and became very pleasant. I have remained at No. 41 Bond Street all day and have spent this Christmas with Miss Dawson and her sister. It touches the cord of melancholy in my heart when looking back at the past. I find myself separated far, far from all those with whom I spent this day last year. It proves the frailty of all human enjoyments and bids us prepare for another world, and more so as I am unable to penetrate the veil which conceals the future from my eyes.

Friday 26th. Snowed very fast in the afternoon but it did not prevent Miss Dawson, her sister, and myself from paying a visit at Mr. Hart’s in Fourth Street. We were there entertained with some delightful music which consisted of songs, marches, comical pieces, &c. among which was the A. B. C. Duet. We returned home at ten o’clock but not without breaking nearly our necks as the pavement had become covered with ice. It had also ceased snowing. I retired late, quite fatigued with walking and visiting.

Saturday 27th. Miss Dawson and myself ventured out to take the air and to do errand. We directed our steps down Broadway. It was quite amusing walking along to see the people twisting and turning in all directions to prevent themselves from falling as there was so much ice upon the pavements. We first visited the Intelligence Office, then the market which was crowded as usual with persons of all classes. We called upon Miss Stites in Amity Street but were disappointed in seeing her as she had returned to her home in New Jersey to spend the Christmas holiday.

Sabbath 28th. In the morning attended the Baptist church in Amity Street in company with Miss Dawson, the casual companion of my walking and visiting. I heard an excellent sermon delivered by the Rev. Mr. Williams. The text was, “It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.” He concluded with a few remarks upon the close of the year which will now soon take place. Spent the time between morning and afternoon service in learning a bible lesson. In the afternoon, attended a Presbyterian church in Thompson Street. A stranger preached. The text was, “We will not have this man to reign over us.” I was not pleased with the sermon as the preacher, I think, introduced some very inappropriate comparisons. Spent the evening in reading and in reciting my bible lesson.

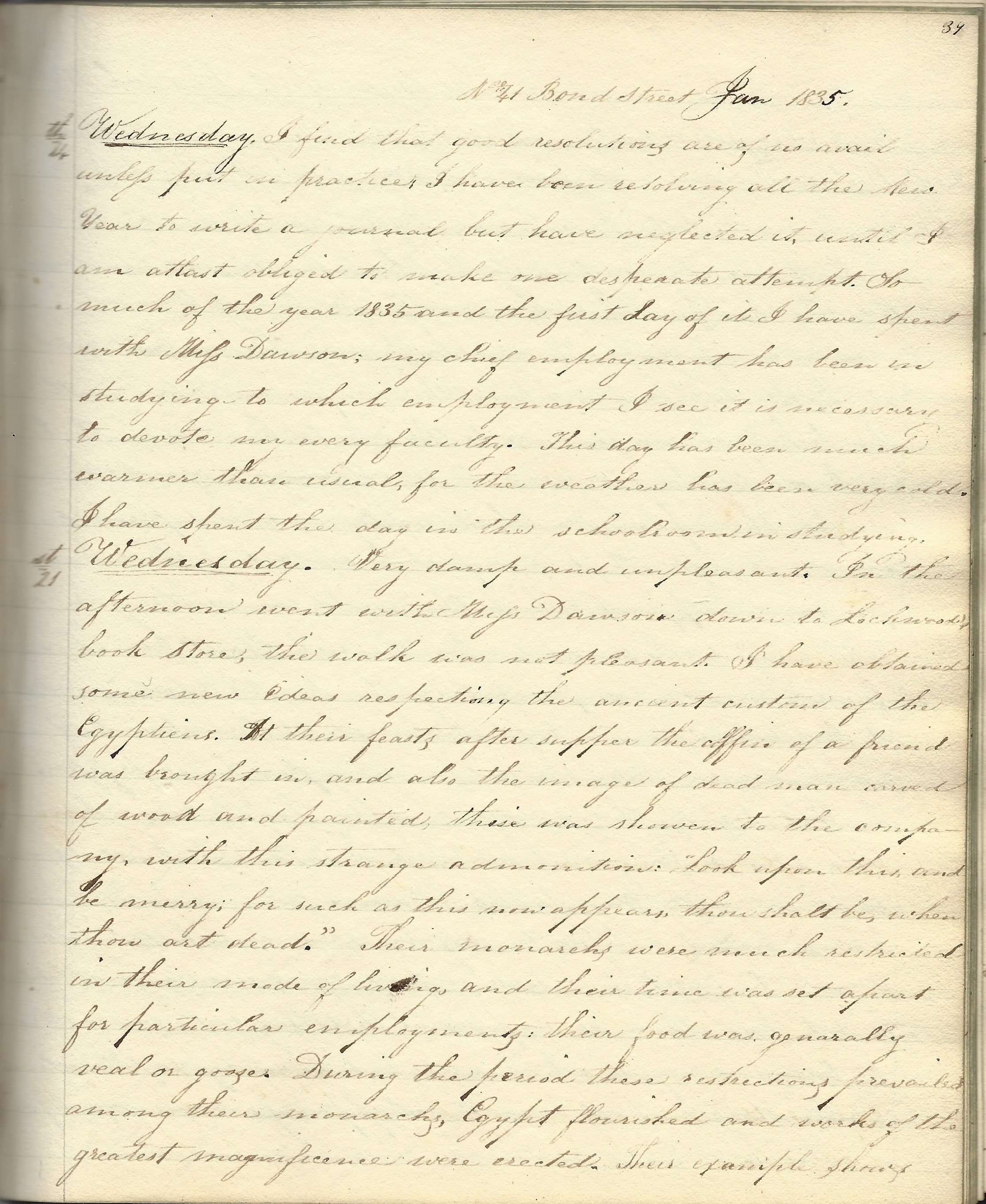

Wednesday, January 14, 1835. I find that good resolutions are of no avail unless put in practice. I have been resolving all the New Year to write a journal but have neglected it until I am at last obliged to make one desperate attempt. So much of the year 1835 and the first day of it I have spent with Miss Dawson. My chief employment has been in studying to which employment has been in studying to which employment I see it is necessary to devote my every faculty. This day has been much warmer than usual for the weather has been very cold. I have spent the day in the schoolroom in studying.

Wednesday 21st. Very damp and unpleasant. In the afternoon went with Miss Dawson down to [Roe] Lockwood’s Book Store [at 415 Broadway below Lispenard Street]. The walk was not pleasant. I have obtained some new ideas respecting the ancient custom of the Egyptians. At their feasts, after supper, the coffin of a friend was brought in and alsothe image of dead man carved of wood and painted. This was shown to the company with this strange admonition: Look upon this, and be merry, for such as this now appears, thou shall be when thou art dead.” Their monarchs were much restricted in their mode of living and their time was set apart for particular employment. Their food was generally veal or goose. During the period these restrictions prevailed among their monarchy. Egypt flourished and works of the greatest magnificence were erected. Their example shows the good effects resulting from self denial.

Friday 23rd. Received a call from P. Truex and his sister. The former brought me a letter from home. By it I was informed of the death of my old aunt Sally Shephard. She resigned her claims to earth on the 17th of this month after having been an inhabitant of it for 97 and a half years. She had lived until all earthly ties were dissolved. The companions of her youth she had seen all go down to the silent chambers of the tomb while she remained to see others—and again others occupy their places. in whose employments and pleasure she was too inform to take a part. Independent of this she possessed a happiness which the world can neither give nor take away. It was founded upon the rock Christ Jesus. Her funeral sermon was preached by the rev. Mr. Roberts (our pastor at Middletown) in the Baptist Church at Middletown, of which denomination she had for many years been a professor. The text of the sermon and also the hymn she had selected for years before, which was “Because I live, ye shall live also.” John, 14th Chapter, 19th verse.

I have learnt a lesson today by experience which I hope never to forget. It is so to improve our manners and habits as not have them so unpleasant that they will cause others to become enraged, which will lead to many unpleasant circumstances and much unhappiness and mortification.

Saturday 24th. In the morning received a call from the Misses Margaret and Mary Downing who were my schoolmates last winter. After having chatted half an hour, we went to see Miss Merry, another schoolmate of last winter. It was a truly delightful visit. We talked over past events and of absent friends. I returned home at two o’clock, spent the afternoon in practicing and in reading. The following lines which came under my observation I have committed to memory as the sentiment contained in them I think is very good.

“Above the lyre, the lute above;

Be mine thy melting tone,

Which makes the peace of all we love

The basis of our own.” [poem by William Hayley]

Sabbath 25th. Rainy. Spent the day at home in reading. An old revolutionary war soldier was buried today named Mr. [blank]. He requested to be buried in the military form and the soldiers were of course out. They passed up this street accompanied by a band of music.

Monday 26th. Took a music lesson of Mr. King. The remainder of the time I was engaged with my studies.

Tuesday 27th. A delightful day. Was called from my slumbers by the well known voice of Miss Dawson which I daily hear in the morning. I have seen in [her?] a good example of what diligence will do and upon that fact I have formed a good resolution.

Sabbath, February 1, 1835. Attended the Episcopal Church in Broom Street.

Middletown, New Jersey, Wednesday, June 10, 1835. In the morning our friends from Sing Sing, N. Y. called upon us. They were five in number including nurses and babe. It is five years since they last visited us. I have been deeply engaged in reading Ivanhoe which although a novel, is equal if not superior to any of its class. I have learnt that bodies in passing from solids to fluids must have an additional quantity of caloric, and in passing from fluids to solids the heat is given out. This is the cause we have it warmer before a snow storm—viz: upon the foregoing rule the heat given out by the water consolidating into snow flakes.

July 4, 1835. This is the 59th Anniversary of our national Independence. We (the inhabitants of the village) celebrated by assembling at the Baptist church in the afternoon where our good rector, the Rev. Mr. Roberts, delivered a good, practical address, one or two ideas of which were:

1st, he thought the day was not properly spent by ringing of bells, shouting, &c. Our God who is an Eternal Spirit is not pleased with such worships and the day ought to be spent in thankfulness to Him, from whom we have received the blessing of liberty and every other blessing we enjoy.

2nd, we must not talk too loudly of our liberty, else the nations will laugh us to scorn. We have at the present time 3 millions of Africans in bondage—as many persons as the white population of the United States at the time they declared themselves independent. After the address, the Temperance Society met. No one joined it.

Sabbath, July 26, 1835. Attended the Baptist church. The Rev. Mr. Kenniesta, stranger from Philadelphia preached. He was in ill health and preached, he said, contrary to the strict injunction of his physician. The text was “And I saw a great white throne, and him that sat on it, from whose face the earth and the heaven fled away; And I saw the dead, small and great, stand before God; and the books were opened and another book was opened which is the book of life. And until the 14 verse which concluded the text, the discourse was very solemn.

Monday, August 10, 1835. This day and Thursday in every week that I spend at home always affords me some pleasure as the mail arrives and brings the newspaper which I always take delight in reading. Have obtained some new ideas from Grimshaw’s History of England. I have made a resolution to be more diligent. In the morning, much of my time was spent watching Grandmama in whose mind the star of reason is quenched.

Tuesday 11th. Rained all day. I have spent the day at home engaged in sewing principally. My dear grandmother has been more composed than for weeks before, and has been much more reasonable. Her bodily health has not been so exempt from disease, but what is the body to the mind. She spent the evening with us in the sitting room and retired to bed very willingly. Papa departed in the afternoon for New York but returned as the vessel did not go on account of the rain. The hours have flown swiftly though silently past, showing thereby with what diligence the present one ought to be improved.

Wednesday 12th. Have been much interested with reading history. Dull and rainy. Spent the day at home.

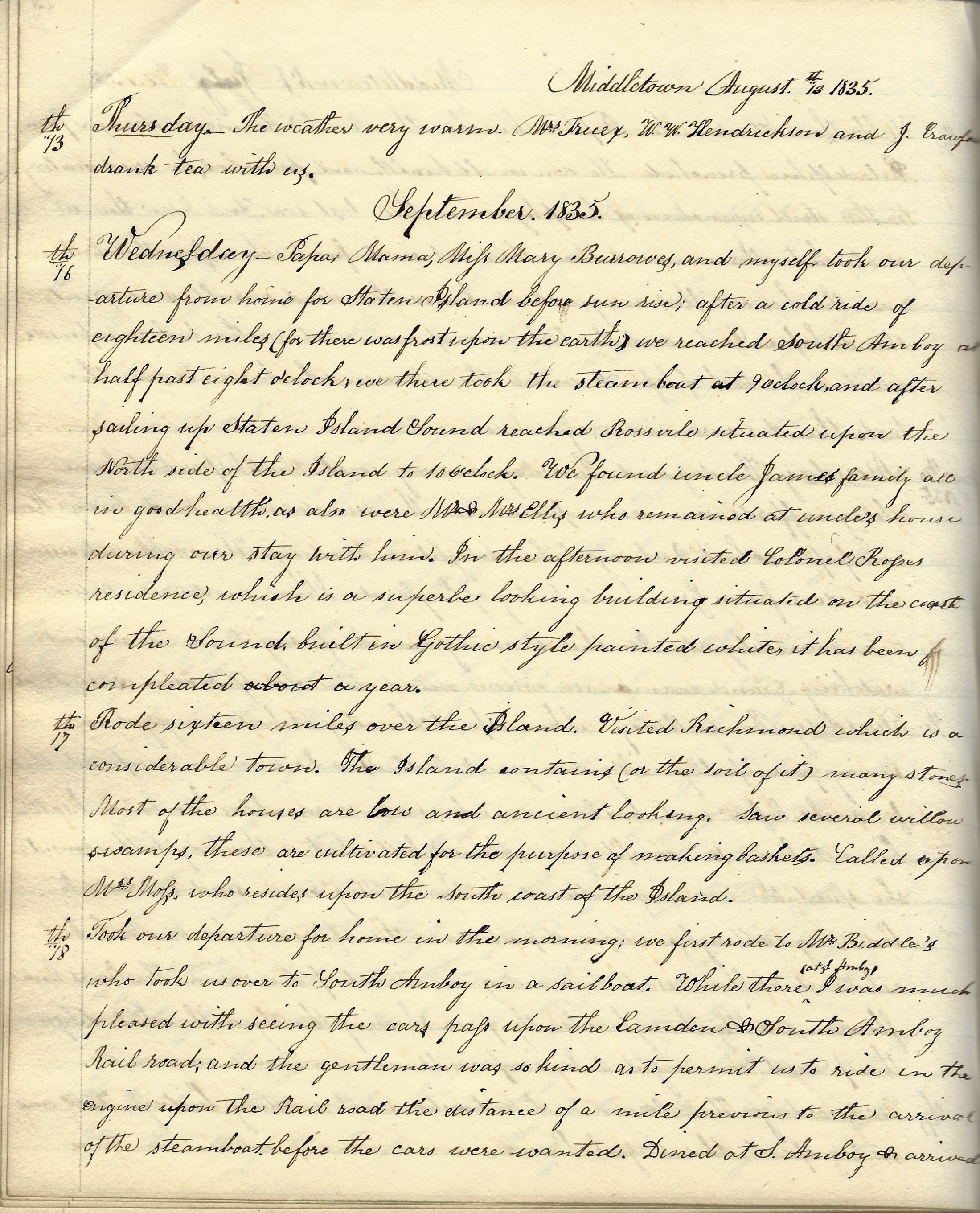

Thursday 13th. The weather very war. Mrs. Truex, W. W. Hendrickson, and J. Crawford drank tea with us.

Wednesday, September 16, 1835. Papa, Mama, Miss Mary Burrowes, and mysef took our departure from home for Staten Island before sun rise. After a cold ride of eighteen miles (for there was frost upon the earth), we reached South Amboy at half past eight o’clock. We there took the steamboat at 9 o’clock and after sailing up Staten Island Sound, reached Rossville situated upon the north side of the island to 10 o’clock. We found Uncle James’ family all in good health, as also were Mr. & Mrs. Ellis who remained at Uncle’s house during our stay with him. In the afternoon visited Colonel [William E.] Ross’s residence which is a superb looking building situated on the coast of the Sound, built in Gothic style, painted white. It has been completed a year.

17th. Rode sixteen miles over the Island. Visited Richmond which is a considerable town. The Island contains (or the soil of it) many stones. Most of the houses are low and ancient looking. Saw several willow swamps. These are cultivated for the purpose of making baskets. Called upon Mrs. Moss who resides upon the south coast of the Island.

18th. Took our departure for home in the morning. We first rode to Mr. Biddle’s who took us over to South Amboy in a sailboat. While there (at South Amboy) I was much pleased with seeing the cars pass upon the Camden & South Amboy Railroad, and the gentleman was so kind as to permit us to ride in the engine upon the railroad the distance of a mile previous to the arrival of the steamboat before the cars were wanted. Dined at South Amboy & arrived at home in the afternoon.

October 7, 1835. Mama and myself spent the day at Uncle Edward Burrowes’s; she returned in the evening. I tarried all night.

8th. Mary and myself spent the afternoon with the Misses Mary and Esther Stout and Mother. Spent a very pleasant afternoon. Returned home with Miss M. B. in the evening.

9th. Arrived at home in the morning accompanied by Mary B. In the afternoon we visite our pastor, the Rev. Mr. Roberts, and family. He mentioned that when he was among the Cherokee Nation at the South, he saw much of the Passion flower grow wild there in abundance. It bears a yellow apple filled with seeds and slime which children eat. Returned in the evening.

10th. M.B. and myself called upon Aunt Beekman after which we walked upon Mr. Osborn’s hill which commands a view of Long Island, Staten Island, The Narrows, &c. Called upon Mrs. Martha Thompson. Mary departed for her home in the afternoon.

Tuesday 22nd. I left home in the morning at 6 o’clock accompanied by Papa and my sister for New York City. We arrived there Wednesday morning, took breakfast at a boarding house in Courtland Street termed the Northern Hotel, Weather very foggy and unpleasant; the streets very dirty. Spent the day in shopping. In the evening we attended the American Institute—an Annual Fair held for the encouragement of the different arts; a mechanic after receiving a premium three times in succession receives the gold medal, It was held at Niblo’s Garden. Machines and articles of every kind are exhibited there, but the great crowd prevented me from viewing them half. Returned to our boarding house at nine o’clock.

Thursday 24th. Spent in shopping.

[October] 25th. Left the city at one o’clock for home. Took passage in a sloop, the same we arrived there in. Reached home at eight o’clock in the evening.

Wednesday, December 16, 1835. Very cold. In the evening had a view of what appeared a tremendous fire in the City of New York. It gave a splendid illumination but its effects were much to be lamented. It is stated to be one of the most extensive conflagrations that has happened to a City since the burning of Moscow. 624 buildings were destroyed, principally stores, situated in the most commercial and wealthiest part of the City, namely that part situated between Wall Street, Broad Street, and the East River. We have to mourn among extensive losses that of the statue of Hamilton and the Exchange. Its ravages were stopped by blowing up buildings before it, thus forming a vacancy. It ceased off Friday afternoon. The engines were prevented from working by the freezing of the water. Thirty millions of property were destroyed by it, thus showing the instability of earthly things. That which had employed the labor of years in collecting, destroyed in a few hours by the devouring elements. It is supposed the fire proceeded from the bursting of a gas pipe.

Thursday 17th. My seventeenth birthday. The arrival of this day recalls to mind past birthdays. Another year has been allotted me and how has it been improved? The answer wounds conscience, not to the utmost of my abilities. the incidents of the past have been various. I still retain hope of improving by past experience.

Friday, December 25, 1836. Christmas. This day was hailed as usually joyfully. Brother George up by twelve o’clock at night running around to all the bedrooms wishing each occupant a happy Christmas. The weather very rainy. I spent the day pleasantly at home. It is the first Christmas I have spent in that dear place in three years.

Tuesday 29th. Left home in the morning at 10 o’clock for New York City. Took passage in the sloop New Jersey, Captain Stony, sailing from Key Port. I was together with Papa on board all night and the unpleasantness of that night is past description. We arrived at the City in the morning. In the afternoon visited the ruins of the fire.