The following letter was composed by Edward H. Johnston, an alumnus of Hamilton College from the class of 1837. Beyond this information, little else can be verified regarding his subsequent endeavors, although it can be reasonably inferred that he pursued a career in education in Virginia, a region characterized by a scarcity of public schools that necessitated the employment of private tutors. Such tutors were primarily recruited from the North and often resided with affluent families aiming to equip their sons for higher education. Furthermore, it is likely that he hailed from the vicinity of Sidney, New York, where his mother was still residing as of 1842.

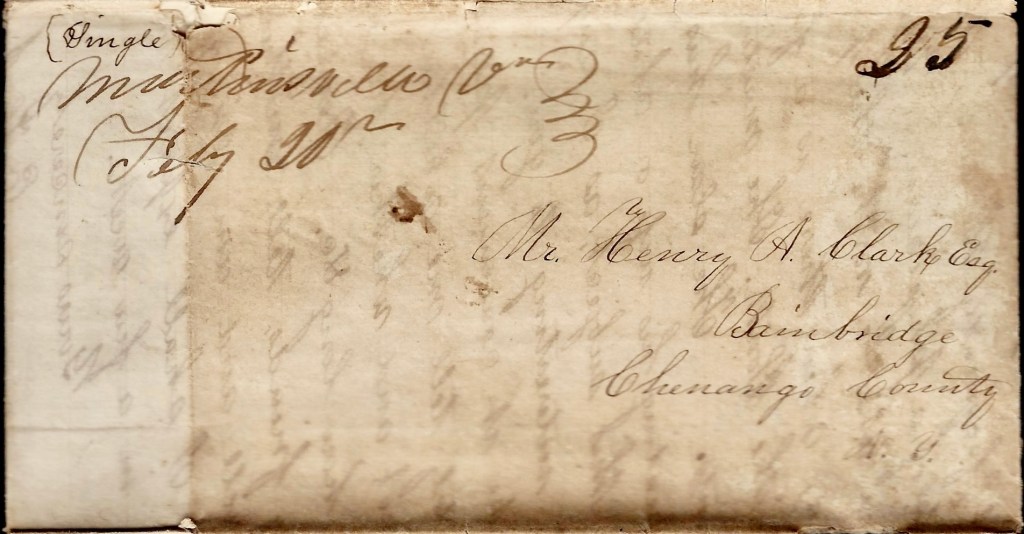

Johnston wrote the letter to his good friend Henry A. Clark (1818-1906), the son of Henry and Catherine (Brown) Clark of Sidney, Delaware county, New York. Henry attended Cazenovia Seminary in the 1830s and graduated from Hamilton College (Clinton, N. Y.) in 1838. He studied law in Buffalo and was admitted to the bar in 1841. By 1842, when this letter was written, he was living in Bainbridge, New York, working as a lawyer. He was a member of the New York State Senate in 1862-63. In 1865 he married Ellen A. Curtiss.

Edward’s letter succinctly addresses the opportunities for teaching in Virginia and recounts his recent visits to Washington City and New York City, where he reunited with former acquaintances. Among them was Horace Dresser, a graduate of Union College and one of the pioneering lawyers who offered his expertise in defending and aiding fugitive slaves. The residents of the Susquehanna River valley, where Edward was raised, alongside the students at his college, exhibited strong anti-slavery sentiments; however, it appears that his time spent in Virginia, witnessing the realities of slavery firsthand, has tempered Edward’s perspectives on the institution, which he articulated in his correspondence.

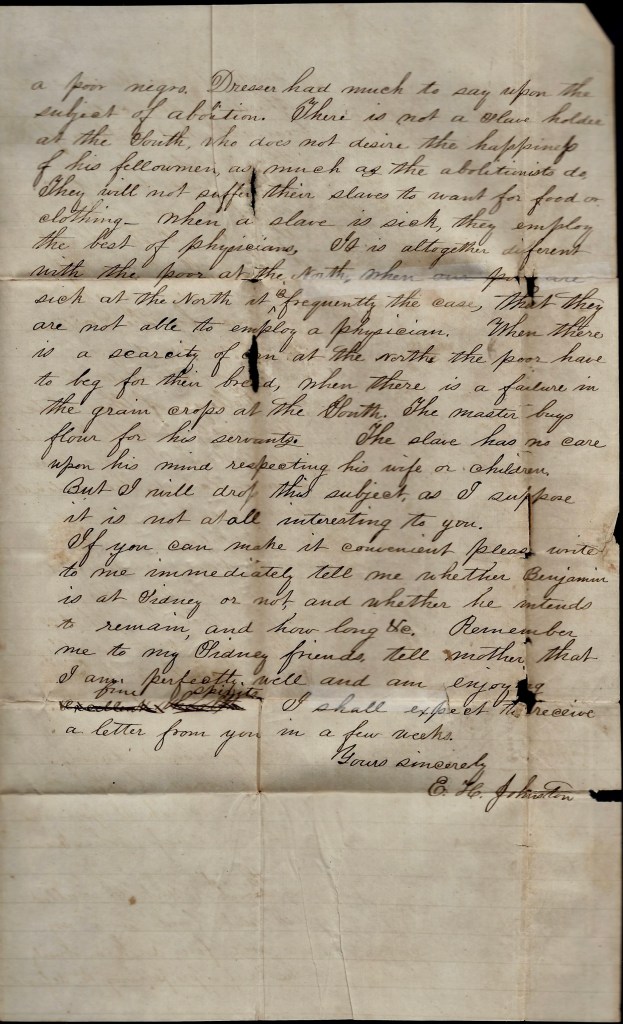

Transcription

Martinsville [Henry County, Virginia]

February 20th 1842

Dear friend,

I promised to write to Benjamin but I think that I shall not comply with the promise since it is somewhat doubtful whether my letter would find him at Sidney or not, if he is yet at Sidney. I can through you inform him respecting those things concerning which he wished to obtain information.

Respecting schools I wish that you would tell Benjamin that I should not think that it was advisable for him to come as far South as this unless he designs to teach longer than one year. If he wishes to teach two or three years, he would run no risk for I am very sure that he would in a very short time succeed in obtaining a school. A teacher is now wanted at Halifax Court House sixty-nine miles from this place. Salary $500 and only 13 students.

I had a very quick trip from Sidney down. I left Sidney Plains on the evening of the 1st of January and arrived at Martinsville on the evening of the 16th January. I spent one day at Kingston, Ulster County and one day at Philadelphia, thus I was only seven days coming a distance of 814 miles.

John B. Fry is at Washington City getting a salary of $1000 per year for officiating as a clerk in the general Land Office. I have received a letter from John since I returned and have answered him. John is doing well—remarkable well considering the advantages which he has enjoyed.

There has been much sickness in Martinsville since I returned. Two-thirds of the citizens of the place have been attacked with a fever which is peculiar to this country at this season of the year. There have been but few deaths yet. A young lady of the same family where I board has recently died. Both black and white are sick and the well being less in number than the sick are scarcely able to take care of them. Fine times for the doctors. They are making their fifty dollars per day.

I have sent two of my students to college—one to Washington College of this state, and the other to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The one whom I have sent to Chapel Hill possesses superior talents. He intends to study law. Remember me to your landlord’s sister and to Miss Davidson, Miss Patience Newell and Miss Adaline Bigelow. I have understood that I said something when at Esqr. Sayre’s which displeased Miss Adaline. Tell her that I now ask her pardon. My respect to Esqr. Sayre and his wife and children—especially to Horace. Remember me to Joseph Bush, Junior and to Mr. Rockwell, his tutor.

The weather has been very pleasant during the month past, during the most of the time it has been uncommonly warm, which, I presume has been the cause of the sickness which is now prevailing.

Returning through New York, I called at Gilbert’s office but did not find him in. I called at Dresser’s office [89 Nassau Street] and found him busily engaged in making out his Brief—preparing to defend a poor negro. Dresser had much to say upon the subject of abolition. 1

There is not a slave holder at the South who does not desire the happiness of his fellow men as much as the abolitionists do. They will not suffer their slaves to want for food or clothing. When a slave is sick, they employ the best of physicians. It is altogether different with the poor at the North. When our poor are sick at the North, it is frequently the case that they are not able to employ a physician. When there is a scarcity of corn at the North, the poor have to beg for their bread. When there is a failure in the grain crops at the South, the master brings flour for his servants. The slave has no care upon his mind respecting his wife or children. But I will drop this subject as I suppose it is not at all interesting to you.

If you can make it convenient, please write to me immediately. Tell me whether Benjamin is at Sydney or not, and whether he intends to remain, and how long, &c. Remember me to my Sidney friends. Tell mother that I am perfectly well and an enjoying fine spirits. I shall expect to receive a letter from you in a few weeks. Yours sincerely, — E. H. Johnston

1 Horace Dresser (1803-1877), the Vigilance Committee’s leading attorney, argued most of the cases before Riker. A graduate of Union College [in 1828], Dresser later became famous as the author of works on legal and historical subjects. When he died, in 1877, the New York Timesrecalled that “at a time when it was exceedingly unpopular,” Dresser had been “the very first lawyer to plead the cause of the slave in the New York courts.” In the 1830s, Dresser was indeed “called upon in all slave cases,” as the Colored American put it. His “services are abundant,” it added, “but [his] remuneration is comparatively nothing at all.”

Against formidable odds, Dresser occasionally won legal victories. Sometimes he was able to obtain writs of habeas corpus to bring to court and liberate individuals held in captivity by kidnappers. Regarding fugitive slaves, however, there was little Dresser or his associate Robert Sedgwick could do, given the attitude of local officials and the duty to return fugitives that was required by the Constitution as well as by both federal and state law. In one instance, Dresser learned that an alleged runaway was about to be taken before the recorder. He rushed to the office only to see Riker rule in favor of the claimant and remark, “I am glad the man has got his nigger again.” [Source: “Gateway to Freedom; the origins of the Underground Railroad” by Eric Foner, Harper’s Magazine, 2024]