This letter was written by Corp. Eben Peck Wolcott (1844-1863) of Co. E, 28th Connecticut Volunteers. Eben was the son of William Albert Wolcott (1810-1879) and Susan H. Peck (1812-Aft1870) of Lakeville, Litchfield county, Connecticut. Eben contracted disease during the siege of Port Hudson and died on 28 August 1863. Eben’s older brother, Samuel W. Wolcott (1842-1864) was killed in the fighting at Deep Bottom Run in Virginia in August 1864 while serving with the 7th Connecticut Volunteers. [The Manuscript Collection at Florida State University has a letter written from Samuel to his brother Eben, dated 26 May 1863] Eben wrote this letter to his mother, Susan (Peck) Wolcott.

The 28th Regiment was the last Connecticut regiment organized under the call for 9-month volunteers. It was composed of only 8 companies: five from Fairfield County and 3 from Litchfield County. Stamford men in the regiment numbered 188.

Eben’s lengthy letter gives us an incredible eye-witness account to the events leading up to the surrender of Port Hudson and of the surrender ceremony itself that took place on 9 July 1863. He also speaks of Rebel desertions and of the danger they faced attempting to enter Union lines manned by Negro soldiers of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards.

See also—1862: Eben Peck Wolcott to Josephine Darling Wolcott published on Spared & Shared 17 in August 2018.

The Special Collections & University Archives of Virginia Tech houses the Eben P. Wolcott Correspondence which contains 41 letters addressed to Eben by family members in Connecticut.

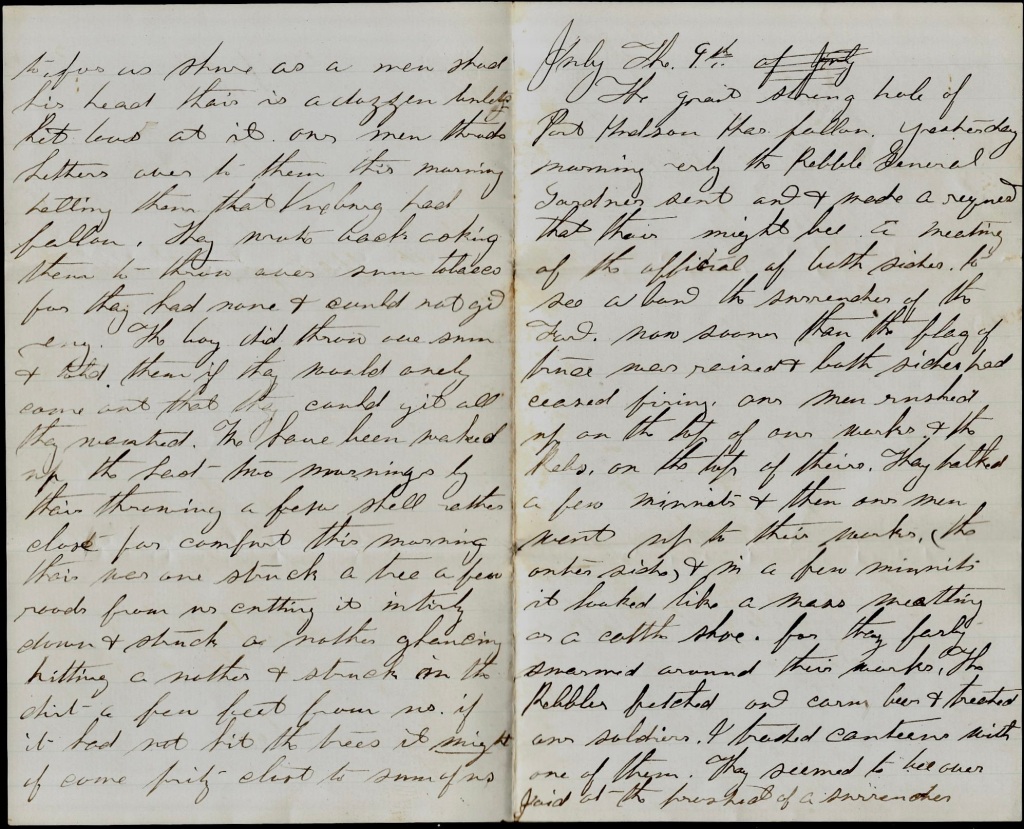

Transcription

Port Hudson, [Louisiana]

July 5th 1863

Dear Mother,

It is three weeks today since we made the charge on the fortifications. I think we have gained some on the Rebels since then. We have batteries closer than we had then & have dug trenches close up to their earthworks. There is now and then a gun (I mean one of the big ones) fired so we have plenty of music the most of the time.

I did not expect to spend the Fourth of July in front of Port Hudson 9 months ago. Then I thought if I was a living that I would be home. The boys claim that our time has already been out three different times. I guess when the government gets through with us, they will tell us of it. There is a possibility that we will be at home in August & then we may not. If this place is taken before long, I think we will be at home in August.

Our regiment has been out in front in the trenches now six days. I should of been with them if I had been well enough. But I am feeling much better than I have for the past few days. I shall go on duty in a day or two. We have no doctor in our regiment now—one being left at Brashear City in charge of a hospital and the one assistant left in charge of our sick, & doctor [Ransom P.] Lyon is sick now 1 so we have a doctor from another regiment. Wright & Burns are down today. They have drawed their new suits and look a little more like soldiers than we do for we are rather dirty and shabby. They start home on their furlough the 15th of this month—60 day furlough.

There is no use in my trying to describe what is going on here for I only see a small portion of 5 miles of earthworks & the papers will give a more correct account than I can & I have a most miserable pen—the only one I have—and it has been in use over a month & that all through the company for I am about the only one that has a pen and ink in the company. I was just a thinking where you was today—whether you was at home or with the friends down east. I shall wait very patiently for another mail but may not get another till we get back to New Orleans. I got two letters from Daniel the last mail. I have not written him in some time but I shall the first opportunity.

July 7th. I am feeling very much better—as well as I expect to till I get home again. We have heard most glorious news today (if it be true & it is said to be official news), that Vicksburg has fallen on the Fourth of July. 28,000 prisoners, 280 field pieces, 80 siege guns. I rather think the Rebs though there was something up for we had heard and played brass bands all the forenoon & then ended off with the salute (they were not blank cartridges as they are North). They are getting more guns in position every day. In a few days, I shall look for the downfall of this place. The last two men shot yesterday—shot out in the trenches. There is more or less lost every day. Our regiment has been very lucky since we have been in the trenches. But the Rebs are death on the Negro regiments here. 2 There is more in proportion of them killed than there is of the white soldiers. But in return, the Negroes are death on them. There doesn’t a Rebel get through near them alive. If there are deserters coming in, it makes no difference. They say that the Rebs will kill them if they get a chance & it is now more than fair for them to do the same to them, they think.

There was quite a number of deserters came out yesterday. Some of them got shot in coming out. They said there would be more come out but they was afraid to for as sure as a man showed his head, there is a dozen bullets let loose at it. Our men throwed letters over to them this morning telling them that Vicksburg had fallen. They wrote back asking them to throw over some tobacco for they had none & could not get any. The boys did throw over some & told them if they would only come out, that they could get all they wanted.

We have been waked up the last two mornings by their throwing a few shells rather close for comfort. This morning there was one struck a tree a few rods from us, cutting it entirely down and struck another glancing, hitting another & struck in the dirt a few feet from us. If it had not hit the tree, it might of come pretty close to some of us.

July 9th. The great stronghold of Port Hudson has fallen. Yesterday morning early the Rebel General [Franklin] Gardner sent out & made a request that there might be a meeting of the officials of both sides to see about a surrender of the fort. No sooner than the flag-of-truce was raised & both sides had ceased firing, our men rushed up on the top of our works & the Rebs on the top of theirs. They talked a few minutes & then our men went up to their works (the outer sides) & in a few minutes it looked like a mass meeting or a cattle show for they fairly swarmed around their works. The Rebels fetched out corn beer 3 & treated our soldiers. I traded canteens with one of them. They seemed to be overjoyed at the prospect of a surrender.

The commissioners met at 9 a.m. I know not the conditions of surrender except the officers retain their side arms. Yesterday afternoon at 4 o’clock there was one brigade of our men marched into the fort. 4 This morning the biggest part of the troops marched in at the right and left with the bands playing at the head. The Rebel troops was drawn up in line over near the river side—that being the only level place that I saw inside—and troops marched up in front of their troops so the two armies were a facing each other about 3 rods apart; our troops forming two lines of battle & theirs only one. After the lines formed, there was a company of marines fetched in a flag staff and it was raised right in the rear of the Rebel line upon a battery of theirs & the Stars & Stripes run up. And then our generals & their staffs rode up in front of the Rebel generals & staff. One of our aides rode up to [Maj. Gen. Franklin] Gardner and told him that all was ready. Gardner rode out, lifted his hat to our general, turned around, called for his troops to [come to] attention. They ordered them to ground arms. Then there was some conversation passed between the two generals that I could not hear & the surrender was over. 5

The surrender was not made to General Banks but to one of the other generals. I could not learn the name but probably shall see it in the papers. There is about 6,000 troops in the fort in all, between thirty-five and 40 hundred official soldiers at the breastworks. There was hardly a gun in the fort but what had been dismounted & in fact, our gunners would knock them over as fast as they could put them up. The most of the fortifications inside are natural, with a little artificial work added to them, making them very strong—ravines after ravines that was most impossible to get through. Our artillery created havoc with them & they was near starved out. The Rebels were very anxious to know what we was a going to do with them—if we was to parole them or keep them prisoners, and if so, where we would take them. 6

The air is very impure in the fort. There has been a great [many] men, horses, and mules killed & have not been buried. If I can get a chance, I mean to go in again but they have a guard on and will neither let a man in or out unless he can steal in through the lines. That was the way I had to do today. I spent 7 hours in the fort & did not go half way around it. It was so very warm in the middle of the day that got pretty near tired out & had to come in. But I saw what I went to see—the surrender. A part of our regiment is out doing guard duty and the rest is still in the woods. You will get the news of the surrender long ere this reaches you & all the particulars with it so I will not try to tell any more.

I think there is a prospect of our staying here a week yet and then probably we will start down the river. If I had of only been to home now, there would have been a good chance for me to of enlisted in the 6-month regiment and gone into Pennsylvania but I am not one of the lucky ones. I hear today that Arlo Wolcott of Norfolk was killed in the fight of the 14th of June. He was in the 49th Massachusetts Regiment. He was an orderly sergeant. 7

I should like to know what luck Lee had met with in Maryland & Pennsylvania. I hear that some of the 2 years and 9 months men have volunteered to go into Pennsylvania. We got a small mail yesterday but I got none from home. I got one from Daniel after he got to St. Augustine & one from David Curtis. I wrote to him while at Brashear & one from Ettie Wolcott. She wanted to know what was the matter with you all. She had not heard from you since she left Salisbury. Samuel was well when he wrote. If I have time, I must write him today for it has been some time since I have written him.

I haven’t much time to write and therefore have to hurry it off rather faster than I would like to. I take notice that the sick are getting well fast. They have done remarkably well for the last day and a half. It is possible that I shall not write again very quick for I am thinking we shall begin our way home before many weeks. I am as well as ever at present. I don’t know as I have time to write more today.

From your affectionate son, — E. P. Wolcott

1 Surgeon Ransom P. Lyon died of disease on 6 August 1863.

2 The two Negro regiments were the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards who had been used by Banks in a futile assault on the Rebel works at Port Hudson on 27 May 1863. Most of these soldiers were recruited in New Orleans and were underprepared for the attack but their enthusiasm impressed General Banks who praised them afterwards.

3 Due to the chronic shortage of drinking water during the hot summer months and the severe drought, the Rebels made a weak beer with corn, sugar and molasses which was kept in barrels at their entrenchments. [See Forty Days and Nights in the Wilderness of Death].

4 Though the surrender terms were hammered out and signed on 8 July 1863, Gardner requested that the official surrender not take place until the morning of the 9th. According to Edward Cunningham’s book entitled The Port Hudson Campaign, 1862-1863 (page 118), this delay was exactly what the Rebels wanted so that any who wished to try to escape during the night might do so, which many of them did by swimming downriver under cover of darkness.

5 Wolcott’s eye-witness account of the surrender ceremony at Port Hudson is consistent with that posted on the American Battlefield Trust which reads, “Port Hudson surrendered on July 9, 1863. At 7 a.m., General Gardner’s ragged army formed in line along the river by his headquarters. As the Federals marched across the shell-blasted soil to the river, they could hear the booming of the guns in Battery Bailey firing a 100-shot salute. Arriving at the river, the Union troop wheeled right and lined up facing their former foes. Gardner offered his sword in surrender to Brig. Gen. George Andrews. Andrews returned it to Gardner in honor of his brave defense of his post. The Confederate infantrymen then put down their arms. There were no cheers as it Stars and Bars were lowered, only proud, defiant silence on one side and respectful silence on the other. That changed when the Stars and Stripes fluttered from atop the flagpole. The ragged, gray-clad men were still quiet, but the huzzahs from the blue-clad ranks more than made up for their silence. Captain Jacob Rawles’ 5th U.S. Battery fired a salute of 34 shots as the American flag went up the pole.

Another account of the surrender ceremony appears in “Life with the Forty-Ninth Massachusetts Volunteers,” which reads: “The ceremony of surrender…was conducted by Brigadier-General Andrew, General Banks’s chief of staff. The spot chosen for the ceremony was an open area, near the flag-staff, opposite the centre of the river batteries, and very near the bank. Along the main street the soldiers composing the garrison were drawn up in line, having all their personal baggage, arms, and equipments with them. General Gardner and staff, with a numerous escort, occupied a position at the right of the line. By 7 o’clock our troops marched into the works, headed by the brigade which had volunteered, a thousand strong, to storm the place in the next assault. Colonel Birge, of the 13th Connecticut regiment, was in command of this storming party. It was fitting that they should lead the way with the flag of bloodless victory, who had volunteered to do so with bayonet and sabre. Artillery closed in with the infantry, and as the grand cortege swept through the broad streets of Port Hudson, with the grand old national airs for the first time in many months breaking the morning stillness, the scene was most impressive and soul-stirring. Never did music sound sweeter, never did men march with lighter step, or greater rejoicing, than our troops, as they came into the place which had cost the lives of many of their gallant comrades. All the sorrow for their losses, and all the joy for their present victory, came to the mind at once. But every private bereavement was instantly forgotten in the nation’s great gain, and every man justly seemed proud to have had a part in one of the greatest triumphs of the war. Passing directly across from the breastworks on the land side to the river batteries, the column then marched by the right flank, and afterwards halted and fronted opposite the rebel line. General Andrew and staff then rode up to receive the sword of the rebel commander. It was proffered to General Andrew by General Gardner, with the brief words: “Having thoroughly defended this position as long as I deemed it necessary, I now surrender to you my sword, and with it this post and its garrison.” To which General Andrew replied: ” I return your sword as a proper compliment to the gallant commander of such gallant troops—conduct that would be heroic in another cause.” To which General Gardner replied, as he returned his sword, with emphasis, into the scabbard: ” This is neither time nor place to discuss the cause.” The men then grounded their arms, not being able to stack them, since hardly one in ten of their pieces had a bayonet attached. They were mostly very rusty and of old style. Quite a number of the old Queen Bess pattern were included among them, having a bore half as large again as the ordinary musket. Most of the cartridge boxes were well filled, but the scarcity of percussion caps was universal. An officer of the garrison, in explanation of this fact, remarked, that this very scarcity of caps was the reason that the men were allowed to cease firing on the right and left for several days. The number of men surrendered is over five thousand. Of these nearly four thousand are ready for duty. The remainder are in the hospital from sickness or wounds. There were six thousand stand of arms, with full equipmnents. The troops are some of the best in the Confederate service; many of them were at Fort Donelson, and all have been at Port Hudson since the battle of Baton Rouge.“

6 Sometime after the surrender, Banks made the decision to parole the enlisted men and non-commissioned officers who were allowed to go home. Banks erred in releasing the prisoners, however, because the paroles were approved only by Gardner who was himself now a prisoner-of-war. Declaring the paroles illegal, Jeff Davis ordered the men to report for duty after a brief furlough and they were sent back into action. About half of the Rebel officers were sent to Johnson’s Island prison camp; the other half to the US Customs House prison in New Orleans. [Source: The Port Hudson Campaign, 1862-1863, page 120.]

7 Wolcott may have his facts wrong on this identity. The Orderly Sergeant in Co. H of the 49th Massachusetts was named Joseph B. Wolcott. He was killed by a sharpshooter on 23 June 1863 at Port Hudson.