The following bitter and heartrending letter was penned by Jonathan W. Larabee (1837-1914) about four weeks after the Battle of Fredericksburg to his aunt back home in Vermont. Jonathan was the son of Alexander Larabee and Sarah F. Williams of Addison county, Vermont. He was employed as a miller and farmer when he married Nellie Fogerty (1841-1909) sometime prior to his enlistment on 7 September 1861 as a private in Co. H, 5th Vermont Infantry. This Regiment was part of the Vermont Brigade, veterans of many battles and noted for its losses as well as for its heroism. In the Battle of Savage’s Station on 29 June 1862 (part of the Peninsular Campaign), the 5th Vermont lost 188 out of 400 troops in just one-half hour of fighting. Their most costly battle, in terms of overall losses, prior to when this letter was written, was Fredericksburg in mid-December 1862. This battle—in which Union casualties exceeded 12,000—was a humiliating defeat and further eroded the patriotic sensibilities and fighting spirit of the Union troops. In a letter written ten days after the Battle of Fredericksburg, one of Jonathan’s comrades in Co. H by the name of Robert Pratt captured the sentiments of the dispirited troops when he wrote, “Thousands after thousands of men being killed and made crippled for life —all for what? God only knows… This is not only what I think, but most every other soldier…A lot of them are deserting. Who knows who will be next.”

Larrabee, responding to a letter from his aunt which may have disparaged his lack of patriotism, rales against the purpose and the carnage of “such an unjust and unholy” war, singling out emancipation as a cause not worth fighting for. He goes on to state that if he is not discharged, he will for sure desert to Canada, and that he doesn’t care what his Aunt or any other family member thinks, or, for that matter, whether he even lives or dies. We learn that his aunt has talked his wife Nell from sending him civilian clothes to make good his thoughts of desertion. There is also a statement of his “playing off” (feigning illness) to avoid caring out his duties as a soldier—particularly going into battle. This is a poignant story of an angry and alienated man who just doesn’t want to fight anymore and, in the process, seems to be about to turn his back on his fellow troops, his family, and his country.

Despite their travail, neither Larabee nor Pratt deserted (though over a hundred others in the regiment did before the war ended). Larabee remained a member of Co. H and went on to fight many more battles as a Union soldier, being wounded on 19 September 1864 in the Battle of Opequan in Virginia. He was discharged as a veteran on 29 June 1865 after nearly 4 years of service. He lived many more years thereafter before dying in approximately 1890 in Rutland, VT.

[Note: This letter is from the private collection of Richard Weiner and was transcribed and published on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Transcription

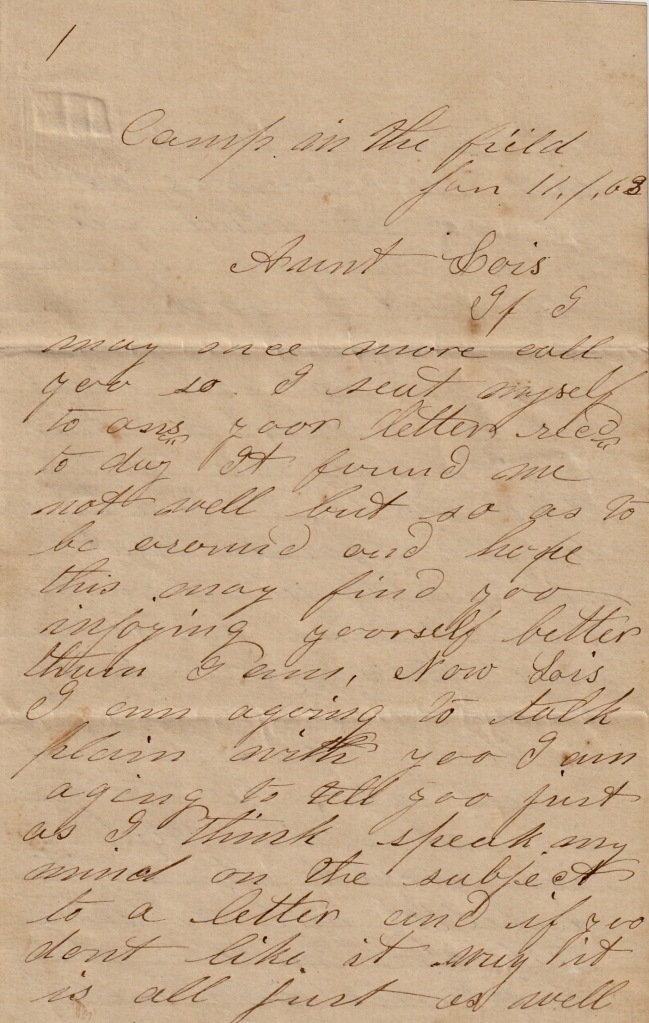

Camp in the field

January 11, 1863

Aunt Lois—if I may once more call you so, I seat myself to answer your letter received today. It found me not well but so as to be around and hope this may find you enjoying yourself better than I am.

Now Lois, I am agoing to talk plain with you. I am agoing to tell you just as I think speak my mind on the subject to a letter and if you don’t like it, why it is all just as well. Not that I wish to hurt the feelings of you or any other friends—if I may so call them—but that I wish to have you understand that there is not the least bit of honor in this unjust war. And more than that, it is a disgrace to the soldier that will fight in such an unjust and unholy cause. And there is no more signs of its being settled than there was a year ago. The thing of it is just here—there are men cooped up in cities perfectly out of danger that are making money. They are doing well. They cry, “Push on!” Well, we do and lose fifteen or twenty thousand men. [When] a dispatch is sent to Washington of our loss, it is looked over with a critic’s eye and then what do they say? “Why what is that? Twenty thousand men? That is nothing out of six or eight hundred thousand men. Oh, that is nothing.”

I suppose you had rather I would be murdered and cut up into pieces than see me get out of it any way only honorable. You don’t have to suffer the pain. You are alright. Go it down there in Virginia and you might as well say we are doing well enough here in Vermont. But I will ask you one question, what are we fighting for? It is impossible for you to answer that question unless you say to free niggers? That is all. There is no Union freed by it—no country saved. But there is an enormous amount of lives lost. But [that] is [apparently] of no account. That is what they enlisted for—to be shot. But never mind the soldiers. Save them cursed niggers, let it cost what it may in blood or treasure.

But there is one thing very certain—that is that it will not cost me much blood unless they catch me for I am bound to never go with them again near enough to the enemy to get shot. I had as leave they would catch me too as not. I don’t know as I have much to live for more than a wife. The rest seem to take up against me—some in one way and some in another. But it is all well enough. I can take care of myself without depending on Vermont. There is just as good people in Canada as there is in Vermont and they get as good living there as they do in the United States.

Nell said Mr. Catlin said he thought the war would be settled in three months. He made a sad mistake. He meant three years or longer perhaps. You may think I am rather hard on you but if I should write my mind, you would think this a very pliable letter. I am a full-blood Democrat myself and that is a rare thing in Vermont and it is not only me but all of the blue coat soldiers as you may call them (for you can’t call them Union—no, far from that, and every day on the decline).

“This murdering men for the fun of the thing don’t set on my stomach at all. But don’t never say any more about a man gaining any honor here I this unholy and unjust cause for there is none to be gained.”

–Jonathan W. Larabee, Co. H, 5th Vermont Infantry, 11 January 1863

Now you may take this letter as you will for I mean every word of it and more too. If I can’t play off and get my discharge, I shall go to Canada or start for there at least for I never can endure this long. This murdering men for the fun of the thing don’t set on my stomach at all. But don’t never say any more about a man gaining any honor here in this unholy and unjust cause for there is none to be gained. I can see it here but you only get the hearsay of the thing which probably sounds very well to you up there but here is where you can see it one day after another. If a man is sick and can’t go and falls out of the ranks, he is cashiered, his pay stopped, sent to Harper’s Ferry to perform so many weeks hard labor with ball and chain.

Well, I must close. Give my love to all the friends. This from, — J. W. Larabee

You have talked Nell out of sending clothes and it’s all right but I believe I can raise money enough to buy a suit of clothes when I get to some little town where they keep them.