(Kevin Kilcommons’ Collection)

The following letters were written by Andrew J. Lane, Jr. (1841-1925), the oldest son of Andrew Lane (1818-1899) and Susan S. Simpson (1820-1894) of Rockport, Essex county, Massachusetts. Andrew had two brother who are mentioned in these letters—Ivory Lane (1842-1869) and Leverette Lane (1844-1929). His younger siblings included Horace (b. 1847), Franklin (b. 1852), John H. (b. 1855), and Susan (b. 1857).

Andrew enlisted on 27 November 1861 as a private in Co. D, 32nd Massachusetts Infantry. He was promoted to corporal prior to his being wounded at Shady Grove Church Road on 30 May 1864 and he was discharged on 1 December 1864. According to the regimental history, Company D was recruited in Gloucester, and was almost entirely composed of fishermen and sailors and had a reputation for unruliness. It was commanded by Captain James P. Draper. The late Adjutant-General James A. Cunningham was First Lieutenant, and Stephen Rich, Second Lieutenant.

[Note: There are reportedly sixty letters in this collection that I will be adding to this webpage as I get them transcribed.]

To read letters by other members of the 32nd Massachusetts Infantry that I have transcribed and published on Spared & Shared, see:

Luther Stephenson, F&S, 32nd Massachusetts (1 Letter)

Edmund Lewis Hyland, Co. F, 32nd Massachusetts (1 Letter)

William Litchfield, Co. F, 32nd Massachusetts (4 Letters)

Letter 1

Fort Warren, [Boston Harbor]

December 5, [1861]

Dear Father,

I take this time to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and hope you all are the same. I like it up here first rate now. The first day we came up here, we hadn’t much to eat. They marched us in and we scambled and get a piece of bread. That’s all we had. Dipped that in a pail of tea. That’s all we had that night. We have good grub now—corned beef and beans. We have got good places to sleep. Got a sack filled with straw. We lay in the fort. Have a fire all night. There is four companies up here now. We don’t drill much yet. We have to stand guard. We have to stand 3 days in a week; go on two hours then stay off 4 so that makes 8 hours out of 24.

There is about 1200 prisoners up here we have to guard. That is all we have to do. There is all kinds of prisoners here. Some of them are dressed up as nice as any gentleman you ever saw, Some looks like the Old Harry [the Devil]—Hatteras prisoners. I was on guard last night. I have seen Slidel & Mason. 1

No more at present. Give my best respects to Johnny and tell him I wish he could see us up her and see the rebels. I don’t know but we shall stay here until the war is over. If I find out that we are, I shall send home after some things. I suppose we shall know before long. Give my love to all the folks. No more at present. — Andrew Lane

Direct your letter to me Coo. D in 1st Battalion, car of Capt. [James P.] Draper.

1 Fort Warren at this time was occupied as a depot for Confederate war and state prisoners during the winter of 1861-62. In February 1862, a detachment of prisoners from Fort Donelson were sent to Fort Warren— “mostly long, gaunt men, given to wearing sombrero hats, and chewing tobacco. With this party came Generals Buckner and Tilghman.“ [The Story of the 32nd Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry, by Francis J. Parker, Colonel]

Letter 2

Fort Warren [Boston Harbor]

April 6th 1862

Dear Father,

I take this opportunity to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well. I received a box last Sunday by Joseph Sewall. The pillow case fits pretty well but it full large.

They put us through drilling now. Our parade ground is dry and hard and in good order now but it snowed last night but it’s gone now. It is my turn to go on guard tomorrow.

I was on guard a week ago last Saturday night and was laying on the bench asleep [when] one of the fellows came in and said the garrison was alarmed. I springed up and grab my gun from the rack. She was all loaded and capped. When I got out, there was all the company drawed up in a line of battle. I couldn’t think what was the trouble. I thought the prisoners had risen [up] or the [Confederate ironclad] Merrimac had come. Come to find out it was done to see how quick the men would be on hand. Most all our fellows were in their bunks asleep with their boots off. They were all equipped, fell in and out on the parade ground in line of battle in 4 and a half minutes, all ready for a fight. Some of the companies were longer than ours. All 6 companies were out in 6 minutes. It was work, I tell you.

I don’t know of anything about so I must close. I am going to put some rings in and you can do what you please with them. Give one to John, one to Frank. Give Mary Wade Smith one. Do what you have a mind to with the rest.

[Joseph H.] Wingood is going home tomorrow, he expects, so I will send it by him. From your son, — Andrew Lane

Write all the news.

Letter 3

Fort Warren

May 21st 1862

Dear Brother,

As I have plenty of time I thought I would write I am well, live and kicking and hope you all are the same. I received your letter last night and was glad to hear from you for I haven’t heard from home since [Joseph] Wingood came back.

You stated in your letter that Alexander was dead. What was it that ailed him? I received a letter from Solon last week. He didn’t say anything about the prospect down there. I guess it ain’t much.

We was paid off two months pay last Wednesday. We was paid up to the first of May. We have drawed more pants. There was new hats came for us last night. It has been hot up here inside of the fort drilling in the middle of the day.

Caleb Farr was up here last Monday with a load of sand. I was on guard outside and went down [and] board of him two or three times. He thought the war would soon close. Everything looks nice up here now. The grass looks green and forward around here. I shall be home on a furlough in about a week from next Monday if nothing happens. Bane will be at home the first of next week. I expect his turn comes before mine does. I don’t know of anything more to write now so I must close now.

Write soon. Tell Ivory to write. From your son, — Andrew Lane

Give my best respects to Rob and all the folks.

Letter 4

Fort Warren [Boston Harbor]

May 26, 1862

Dear Father,

I take this time to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well. We had orders come for us to be in Boston at 3 o’clock this afternoon to go to Washington. All six companies is going. Major Parker came down here last night at 2 o’clock. Our cooks are cooking 3 days rations. I am packing up some boxes to send home. Look out for them. Tell Mother to keep cool—not to fret about me for I shall do the best I can. This is quick notice for us, I tell you. They say that Gen. Banks has been cut to pieces and the rebels are advancing onto Washington.

Give my love to all the folks. We are getting ready for to go so no more this time. So goodbye. I will write as soon as I get there and tell you all the news.

From your son, — Andrew Lane

I haven’t got time to write any more. Have good courage for I have got [it]. Don’t worry about me. Goodbye. Bane [Vane? Cane?] was coming home tomorrow. I was coming next Thursday but orders some so we can’t. 1

1 After months of garrison duty at Fort Warren, most of the members of the 32nd Massachusetts were “glad to be out of jail, some said—glad to be moving to the front; all desiring to see that actual war for which they had passed through long and careful training, and anxious as new troops can be, for a share in the realities of the campaign.” [The Story of the 32nd Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry, by Francis J. Parker, Colonel]

Letter 5

Camp at Washington D. C.

Wednesday afternoon, [May 28th 1862]

Dear Father,

I take this time to write to you. We have just arrived here about 4 o’clock. We have been on the road since Monday afternoon. We haven’t stopped but twice since we started and that was in Philadelphia yesterday and got some dinner there [after which] we started again. We left our muskets in Boston and got Enfield rifles in Fall River. When we was at Philadelphia, we heard that there was a mob in Baltimore so we loaded our rifles.

We was accepted in Philadelphia tip top. We got into Baltimore at light this morning and marched through the same street that the Old 6th was attacked. We had no trouble. Flags was flying all around. They took us in and gave us a good breakfast. They cheered us all the way along. We are all hoarse cheering so much. I tell you that everything looks splendid out this way. Grass is almost high ready to mow. Peas all podded.

We had a good time coming out. We come from Fall River to Jersey City in a steamer. She had berths enough to accommodate 1,000. We are here close to the White House in a building. We are going to stop here to guard Washington. There is 8,000 troops here now [and] 5,000 more expected tonight. These are going off tomorrow. We are going about a mile and a half to the other part of the city on the Potomac to relieve troops to go South.

I can’t write anymore this time. I shall write again son. Direct your letter to Washington D. C., 32nd Regiment Infantry, Mass. Vols., Co. D.

Write to me soon and let me know how things are. I think this is a the nicest place in the world. — Andrew Lane

Letter 6

Washington [D. C.]

Monday, June 23rd 1862

Dear Father,

As I have plenty of time this morning, I thought I would write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and hope all of you are the same. I haven’t heard from you for some time now.

It is warm here. They say we are about to leave here. I think we shall go this week for the officers are packing up their things. They say we are to go to Alexandria. That is about fifteen miles from here. We are going there to guard a railroad track but it is hard telling where we are going. We ain’t doing anything where we are now. Our captain is gone on to Boston with a prisoner.

There was a lieutenant-colonel died in the city and out regiment had to go to escort him to the depot. He was way up by the White House. We had to march about five miles. There was a band there. We marched reversed arms—that is, under our arm, butts up. They all thought up in the city that we was Regulars. They told our officers that it was the best regiment they had seen for they were all young fellows.

When we first got here, we had rather poor grub but have better now. All of us Rockport fellows are all in one tent together. I think we shall leave here this afternoon or tomorrow for I just heard the Colonel tell the sergeants to get their things together so I think we are going right off.

I suppose you will begin haying before long now. I don’t know what to think of this war. I don’t think it will close very soon for they don’t seem to be doing anything as I can see. They don’t print anything in the papers here. I think we shall have to see some fighting before we get out of this.

There is seventeen hundred men to work on the Navy Yard making shells. 1 I don’t think of anything more to write so I must close now. When you write, direct to Washington to be forwarded to 32nd Regiment.

From your son, — Andrew Lane.

1 Members of the 32nd Massachusetts would have had an opportunity to view these activities at the Navy Yard from their encampment at Camp Alexander. The camp was pitched on a high bluff overlooking the eastern branch of the Potomac.

Letter 7

Camped somewhere, don’t know where

Somewhere near Fairfax [Virginia]

June 27th 1862

Brother Joe,

As i have got time now, I thought I would write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and all the rest of the Rockport boys and I hope all of you are the same. We are all of us in one tent together. we have moved since you heard from me last. We had orders to start last Wednesday which [we] did. We started in the morning and marched with our knapsacks on, the brigade train in the rear, 20 of them with six mules each. We had a good cool day to march. We arrived here about 5 o’clock in the afternoon. We came through Alexander. We are about three miles beyond Alexandria.

There is a lot of regiments here. The 99th Pennsylvania, some Indiana Regiment and [the 10th] Rhode Island, and they keep coming all the time. There is a regiment just came. There ain’t but two houses to be seen [and] them are all riddled to pieces. Everything looks deserted out here and everybody gone. Our army has cut all the wood around as far as you can see. Large oaks [have] been cut off here. We are about twenty miles from Washington. I think they are afraid that Jackson would come around this way and try to get into Washington—that is the reason we came here.

The Bloody 69th New York is here and a lot of batteries of artillery. They are practicing here now. They have got 6 horses to a piece. They go around here like lightning, fire, then off again.

When we came through Alexandria, I saw the house where Col. Ellsworth was shot. The house was all ripped to pieces. They say the same flag is flying that he put up there. I saw Henry Robinson the other day before we left and [illegible] and McLain’s brother. They belong to the 14th Mass. Regiment. If you only had such land as there is here to clear up, you would never work on that Dennis pasture—I bet you wouldn’t—for here it is level as a house. There is not a rock to be seen and mellow loam. But anyone wouldn’t want to live here, I shouldn’t think.

We belong to a brigade now—Sturgis’s I believe. I don’t know how long we shall stop here. I expect we are leaving now. I must close. Give my love to all the folks. Tell [illegible] to be good boys. Direct your letters to Washington to be forwarded to 32nd.

From your brother, — Andrew Lane

Letter 8

Fortress Monroe

Laying on board Steamer Hero awaiting orders

July 2nd 1862

Dear Father,

I take ths time to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and hope you all are the same. We had orders come last Sunday night for us to report in Alexandria on Monday and Monday morning we pitched our tents and started and marched to Alexandria—the distance about six miles. We waited there until sundown for a transport when we started for Fortress Monroe—the distance about 200 miles. We anchored in Hampton Roads at nine o’clock last night and went to the wharf this morning and [are] waiting for orders. I think we shall go to Richmond to reinforce McClellan as there is lots of regiments on the way.

Saturday and Sunday before we left, the cars was running night and day bringing troops from Harper’s Ferry to go on to Richmond. There is any quantity of steamers loaded with troops. I never began to see so many steamers and vessels and gunboats as there is here in the Roads loaded with everything. There is six lays here loaded with horses, some with cannon, some with wagons, and a great many with hay if we shall go up the James river.

I haven’t got much time to write for the mail is going off now. I will write as soon as we arrive at our destination. The officers don’t know where we shall go and we may stop off at Fort Monroe yet. We can’t tell. 1

If you write to me, direct to Washington to be forwarded to 32nd Regiment and it will come where we are. I must close now. Write to me soon. From your son, — Andrew Lane

1 “We arrived at Fort Monroe early on the 2d of July, and reported to General Dix, commanding that post. Here we heard of the seven days fighting across the Peninsula, and found the air full of exciting and contradictory rumors as to the incidents and result of the battles. Even General Dix had no precise information as to the whereabouts of General McClellan, but he knew that he wanted more men and wanted them quick, and we were directed without disembarking to proceed up the river until we found the army. Facilities were provided for cooking the necessary rations, and early in the afternoon, after receiving repeated injunctions to take 42every precaution against falling into the hands of the enemy, we weighed anchor and steamed away up the James. Our heavily-laden boat could not make the distance by daylight, and we passed the night at anchor in the river, with steam up and a large guard on duty, and with the early dawn were again underweigh, in search of the army.” [The Story of the 32nd Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry, by Francis J. Parker, Colonel]

Letter 9

Harrison’s Landing

Sunday, July 6th 1862

Dear Brother Joe,

I take this time to write to you to let you know where I am. All of us Rockport boys are all well—the same as we was when we left home. I wrote hime when I was at Fort Monroe.

We landed here the 3rd of July. I tell you, it looked dark when we landed. The army was on the bank of the river. They had retreated back from Richmond to here and the rebels followed them back and was fighting. When we landed we got eighty rounds of cartridges and started up, the mud up to our knees. I never saw such a time in my life there. The men was laying dead and wounded, horses and mules laying dead, and the shells bursting around. We went up to the edge of the woods. I thought we were going right into a fight. I felt just like it. We was drawn up in line of battle at the edge of the wood and halted. Just through this woods was a large field and they took the rebel battery by a charge. They was on the retreat. That was never known to be done before. 1

We stopped there until night when we moved away to the right in the woods and there we stopped. We have been here ever since. This division we are in is the 3rd Reserve. The army and two reserves have gone on before us but I don’t know how far they have gone. There is three regiments in this division that is cut up bad—the 9th Massachusetts, and a Pennsylvania Regiment. We are laying back for them to recruit up. I wish you could see the 9th Massachusetts Regimental flag all riddled to pieces with bullets. The men are all Irish. They only had two officers left in their regiment. They say the rebels fight like the devil. They would come up and put their hands on our cannon when they was firing grape and canister into them and our fellows would put in double charges of grape and canister and mow them down like grass. They all say here that they killed 5 rebels where they killed one of ours.

You folks at home that think that a half dozen men can go through the South had better come out here and try them. They ain’t no cowards. The men say that our batteries would cut regiments down and they would close up again and come steadily on. They wouldn’t flinch a bit for the bullets, but when they come to a charge bayonet, they leave.

There is regiments arriving here all the time now. The Maine 5th was drawn up in line of battle behind us that first day we came but I didn’t have a chance to go and see them but I saw one [illegible] and Steve Parker’s and the fellows are in. He sas the boys are all right but Benson for he is wounded and expects to be taken prisoner. The Maine 5th has gone on the advance. It was cut up pretty bad.

I don’t know what to think of this retreat that McClellan has made. They say that he done it to let Burnsides and Pope come in behind them to Richmond. The fellows say that the rebels are drunk—full of whiskey and gun powder. They [illegible] full of it.

When we come up the river, I saw the Cumberland and Congress that the Merrimac sunk. The Monitor lays off here. She took a rebel gunboat yesterday. All we had to eat the first day or two was hard bread and pork. Now we get beef, bread and coffee. I don’t know how long we stay here. We pitched our tents last night. I think we shall stop here some time yet. Direct your letters to Washington D. C., 32nd Mass. Volunteers. Write to me. — Andrew Lane

We are 16 miles from Richmond now. We are close to the James River. Give my love to all the folks.

1 Col. Parker had the following to say of the regiment’s arrival at Harrison’s Landing on the James river: “At the head of the wharf a mass of men were striving to pass the guard, hoping to get away on the steamer which had brought us. Passing them, we looked for the road up which we were ordered to move “direct.” In every direction, and as far as we could see, the soil which twenty-four hours before had been covered with promising crops of almost ripened grain, was trodden into a deep clay mud,—so deep and so adhesive as, in several cases, to pull the boots and stockings from the soldiers’ feet, and so universal as to have obliterated every sign of the original road. Everywhere were swarms of men in uniform, tattered and spattered with mud, but with no perceptible organization, wading through the pasty ground. On and near the river bank were open boxes, barrels, casks, and bags of provision and forage, from which each man supplied himself without the forms of requisition, issue, or receipt. Everywhere too were mule-wagon teams struggling in the mire, and the air resounded with the oaths of the drivers, the creaking of the wagons, the voices of men shouting to each other, the bray of hungry mules, and the noise of bugle and drum calls, with an accompaniment of artillery firing on land and water. To all these were added, when we appeared, shouts, not of hearty welcome and encouragement, such as we might naturally have expected from an overtasked army to its first reinforcement, but in derision of our clean dress and exact movements—warnings of terrible things awaiting us close at hand—questions as to how our patriotism was now—not one generous cheer.

Officers and men alike joined in this unseemly behavior, and even now when we know, as we did not then, the story of the terrible days of battle through which they had passed, and the sufferings that they had patiently endured, we cannot quite forgive their unmannerly reception of a recruiting force. Through all this we succeeded in finding General Porter’s headquarters, and by his direction were guided to a position a mile or more distant, and placed in line of battle with other troops in face of a thick wood, and then learned that we were assigned to the brigade of General Charles Griffin, division of General Morell, in Fitz John Porter’s, afterward known as the Fifth army corps. As soon as we were fairly in position our Colonel sought for the brigadier. The result was not exactly what his fancy may have painted. On a small heap of tolerably clean straw he found three or four officers stretched at full length, not very clean in appearance and evidently well nigh exhausted in condition. One of them, rather more piratical looking than the others, owned that he was General Griffin, and endeavored to exhibit some interest in the addition to his command, but it was very reluctantly that he acceded to the request that he would show himself to the Regiment, in order that they might be able to recognize their brigade commander.

After a time however, the General mounted and rode to the head of our column of divisions. The Colonel ordered “attention” and the proper salute, and said: “Men, I want you to know and remember General Griffin, our Brigadier General.” Griffin’s address was perhaps the most elaborate he had ever made in public. “We’ve had a tough time men, and it is not over yet, but we have whaled them every time and can whale them again.” Our men, too well disciplined to cheer in the ranks, received the introduction and the speech, so far as was observed, in soldierly silence, but months afterward the General told that he heard a response from one man in the ranks who said, “Good God! is that fellow a general.” We all came to know him pretty well in time, and to like him too, and some of us to mourn deeply when he died of the fever in Texas, after the surrender.

The officers of our Field and Staff found in the edge of the wood just in front of the Regiment, a spot somewhat drier than the average, and occupied it, but not without opposition. A long and very muddy corporal was gently slumbering there, and on waking, recognized his disturbers by their clean apparel as new comers, and thought they might be raw. Pointing to an unexploded shell which lay near him on the ground, he calmly advised the officers not to stop there, as “a good many of them things had been dropping in all the morning.” His strategy proved unsuccessful, for he was ranked out of his comfortable quarters and told to join his regiment. After all, the day passed without an engagement, and the sound of guns gradually died away, until near evening, when the Brigade was moved about two miles away and bivouacked in a wood of holly trees, the men making beds of green corn-stalks, and going to them singing and laughing.” [The Story of the 32nd Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry, by Francis J. Parker, Colonel]

Letter 10

Harrison’s Landing

July 12th 1862

Dear Father and Mother,

I take this time to write to you to let you know that I am well and was glad to hear that all of you were. I received your letter and paper yesterday and was pleased with them. We are laying back in the woods where we landed at first. We have pitched our tents at the edge of woods. It is a pleasant place, I tell you.

There is a plantation here that we are on. The night we came here the corn was up to our shoulders just as far as you could see. They turned in three thousand head of cattle into it the night we came here. I tell you they went into it good. It looked too bad to see them eat that corn. That is the drove that follows the army for them to eat and when they retreated back, they came in before the army. That is the biggest drove that I ever saw. You tell Joe that I should like for him to see them and pick him out a pair of steers for there are some of the best looking cattle I ever saw in my life. They have ate the corn all up and they have moved them over across the street into another corn field.

I don’t think it is so hot here as it is at home. We haven’t done the first thing since we have been here yet but I think we shall move soon. We are back as a reserve. The advance troops are out three or four miles beyond us. They are building forts and entrenchments and I think we shall have to go out and help them. The 5th Maine Regiment is out there. I and [Sylvanus B.] Babson, 1 [Joseph] Sewall, and Pickney went up there the other day to see the boys. We saw [Otis] Wallace & [Charles M.] Coburn and some more fellows. They was glad to see us. [Stephen] Perkins is taken prisoner [or] shot—they don’t know which, for he went out after his knapsack after the regiment had fallen back [and] they never saw him since. Scraper left his regiment before the fight commenced. They haven’t seen him. I saw a sergeant in his company. He says he hopes he never will come back. He thinks he has deserted.

Yesterday Otis [Wallace] and Coburn & Thomas was over here to our camp all day. It rained a little. They look just the same as ever. Some of our boys are gone out after some hogs. We saw four or five over the other side of the plantation and they went into the woods and they have gone to shoot them. Bane is gone with them. I don’t know whether they will get them or not. If they do, we shall have some fresh pork.

I like it out here tip top. It was a hard sight the first day we landed to see the stragglers down at the landing. I should think there was 10,000 that had lost their regiments. The mud was up to our knees and they was laying about in that—dead, wounded, and tired. I thought we was going right into a fight for the rebels threw shells over where we were. Killed horses but they took [their] battery in a short time after that.

Continued [sheet]

I don’t think there will be any more fighting until cool weather and they get more troops here. I think that Burnsides and Pope will get in the rear of them. Fort Darling is about 15 miles up the river from here and they say the gunboats are going to shell them out—that there is a slew of them here. I saw the Monitor that day we landed. The talk is here that they are drafting. I hope they will. That will bring them out. You tell Ivory not to think of going to war for if he knows when he is well off, to stay at home. I suppose if they draft, you and he will hope to stand a draft. But if you are drafted, don’t you come. I didn’t know but if they drafted that Ivory would be for coming in someone’s place for the rebels are careless. They will fire right at anyone’s face.

Old Abe & McClellan was here the other day reviewing the army. It was about 10 o’clock at night when he went by us. They cheered him good. It was so dark that we could not see him very well.

If you could only see the horses and mules there is here, I think your eyes would stick out some. I don’t see any grass out here. All wheat & corn. Fields of wheat that you can’t see the ends of them. I think you are right into the haying now. I heard some time ago that the grass was winter killed bad.

When we came up the James river, we saw the Congress and Cumberland that the Merrimac sunk. Their masts was out of the water.

Tell Ive [Ivory] mind not get cut by that machine when he is mowing. Tell Susan to be a [good] girl. How is Old Fide. He alive yet? Tell John to spread swaths. Write soon. — Andrew Lane

1 Sylvanus Brown Babson was 21 years old when he enlisted on 22 November 1861 as a private in Co. D, 32nd Massachusetts Infantry. He was promoted to sergeant in 1863 and was killed in action at Laurel Hill, Virginia, on 10 May 1864. He was one of the “Rockport Boys.” Babson was the son of Isaac & Mary (Whitman) Babson. He was married to Lucretia N. Sargent on 26 January 1864.

Letter 11

Harrison’s Landing

August 2nd 1862

Dear Parents,

I received your letter and two papers last night and was glad to hear that you was well. I am well and all the rest of the Rockport boys. I wrote a letter to you the other day stating that I and [Sylvanus B.] Babson was detailed for extra guard and we are there yet but expect to come up the first of the week. We went up to camp yesterday and signed the pay rolls and was paid off with two months pay.

We had quite an exciting time night before last. Just after 12 o’clock, the rebels opened fire upon us with shot and shell came where we was fast and [I] think they had a crossfire upon us. And as we was right on the bank [of the James River] and they was on the other bank, both about the same height, and all the army stores & provisions was there, I think they tried to destroy it. 1 We had five tents pitched on the edge of the bank. I and Vane had a shelter tent made of our rubber blankets a little one side from the rest. We was both asleep. The first thing I knew was that I heard something go over us—sounded like a rocket when it starts. I gave Vane a pull and out we went. And they was a coming right along, I tell you. Some of the fellows ran one way and some the other but there was a gang of us laid down flat in a little hollow place. Some went about ten feet beyond, some went into the bank behind. Some burst right over our heads. I expected every moment to get one in the back of the neck. There was four fellows that had been fishing come along close by us and stopped. One says to the other, “This is a dangerous place.” They started to come and lay down where we was [and had] just started when a 12 lb. shot struck where they left, sent the dirt all over us. Then the gunboats opened fire upon them and some siege guns that our folks had planted on the bank. But our fellows soon got the range of them and they left. They fired at us I should [think] an hour. It did not hurt any of our fellows. It killed one fellow a short distance from us. Cut him in two. They shelled the camp away back. There was one shot went through two tents up in our camp but did not hurt anyone.

The boys picked up 4 shots in the morning around our camp. They killed and wounded about twenty men—mostly Pennsylvania and New York men. They killed and wounded eight or ten horses.

Yesterday afternoon about 2,000 troops went across the river and burned eight houses and some small barns. They set them just before dark. They burned most of the night. They came back about 12 at night. This morning they have gone over again. They are cutting away the woods in front of the plantation and have gone away back in ythe woods a scouting. I don’t know how they will make out for they say that there is 40,000 or 50,000 troops above here across the river.

Oh, that night there was seven of our gunboats drawn up ready for the young Merrimac and ram as they was seen up the river. Some think that the firing was to draw the gunboats down but they did not come as there was two already down.

The way I look at it, I think we are pretty well bagged for they [are] in front and behind and all around. If they don’t do something soon, we shall have to cut our way out or surrender up. I call this war a real humbug. It is all a money-making business for the officers but the privates has to take it. I don’t blame the boys for not enlisting. If they knew as much as I do now, they wouldn’t. I pity professor if [he] comes out here where he can’t get a lunch and get only 4 small hard bread and a piece of pork. You tell them to come as an officer and then they can have anything they want—green corn and good hot loaves even. You folks don’t have no idea of this war. I pity Calvin Pool if he goes in the ranks. If a man is sick here, they don’t mind anything about him. I want to see all the men we can have out here and put this thing through and go home, but I wouldn’t enlist if I was at home and knew as much as I do now if they gave me five hundred dollars bounty. You may think by this that I am pretty sick of it. The thing of it is they don’t try to put it stop.

You said something about a box. If you have sent one, write how you sent it and how directed too. They send everything here by Adams Express. Write soon and tell me about it. Write all the news. — Andrew Lane

I enclose a twenty dollar note in this letter. You can use it if you want it or put it in the bank. Give my love to all the folks. Here is a little shiner for sister—one dollar. Tell her that is better than a nigger.

1 Most likely Andrew was detailed as a guard at the quartermaster stores on the banks of the James River. According to the regimental history, “eighty men and three officers were at one time serving as guards over the quartermaster’s stores, on the river bank. It was while they were there, that enterprising John Reb. brought some field pieces down to Coggins’ Point, just opposite to us on the James, and opened fire about midnight, first upon the shipping in the river, and afterward upon our camps. Two of the officers of our detached party, after the freshness of the alarm had passed, were sitting in their shelter tent with their feet to the foe, watching as they would any pyrotechnic display, the flash of the guns, and the curves described by the burning fuses, when one of the guns was turned and discharged, as it seemed, directly at our friends, who, dodging at the same moment, struck their heads together and fell, each under the impression that the enemy’s shell had struck him.

It was on this occasion that Colonel Sawtelle, the officer in charge of the transportation—our quartermaster said he was the only regular officer within his experience who could do his duty and be civil too—emerged from his tent at the sound 53of firing and stood upon the bank gazing silently and sorrowfully upon his defenceless fleet, among which the shells were exploding merrily. Soon his silence broke into a shout to his superior, “Look here Ingalls, if this thing isn’t stopped pretty quick, the A. P. is a busted concern.” In the regimental camp a half mile away, the shelling did no serious damage, but produced some commotion. One of the officers complained that every time that he got comfortably settled for sleep, a shell would knock the pillow out from under his head; in emulation of which story, a sailor in D Company declared that he slept through the whole affair, but in the morning counted twenty-three solid shot piled up against his back, that hit but had not waked him.” [The Story of the 32nd Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry, by Francis J. Parker, Colonel]

Letter 12

Near Arlington Heights

September 3, 1862

Dear Parents,

As we have stopped marching this morning and have got our mail once more, I will try and write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and I was glad to hear that you were. Now I have began, I don’t know what to write.

Anyway, it looks good to see Washington once more for we can see the Capitol all plain from where we are now. I should think it was about 6 miles off. I think we shall stop here for awhile and get rested and recruited up as General Porter rode through our lines this morning and they cheered him. He says now, “Boys, you are going to have a good rest,” so I think by that we are going to lay by for a spell and let them 300,000 take a turn. Porter’s Corps is pretty well used up. Some of the regiments can’t muster only 2 or three hundred men. His Corps done most of the fighting on that retreat from Richmond and it is pretty well used up.

There was fifty men in our company this morning. We haven’t got nary officer. Our lieutenant was taken sick the other day and has gone to Alexandria. A lieutenant from Co. G has got charge of us now. All of our Rockport boys stand it tip top and are well.

I suppose you hear and read and know more about [more] things than I can tell you for I can’t hear nothing. Haven’t seen a paper for twenty-two days since we left Harrison’s Landing and we have been going ever since. For a week past, we have been trying to catch Jackson but haven’t yet and don’t think we will either. He is a smart one. We haven’t had much of a brush with him but some of them has by what I have seen and I don’t think our folks got any the best of him by the loads of wounded that I see them hauling off the battlefield. Our whole army was after him. We have been all through Bull Run and everywhere else. We expected to attack him every day. We kept in the woods so we couldn’t keep the track of him. He would fight one day here, then that night he would start. The next day you would expect to have a great battle [and] the first thing we would hear, he has attacked somebody else 15 or 20 miles ahead. [Then] away we would go there [and] when we got there, [it would be] all over and don’t know where he is. So that is the way that they have kept us a going night and day, rain & shine. I tell you what, it is rough.

I haven’t seen a Southerner left on a plantation on the whole march—all niggers. Every [man] is in the Southern army, I expect. I thought I used to be tired sometimes when I was at home, but I wasn’t. I tell you what, let a fellow get a good soaking, then march 13 or 20 miles over this country. He won’t feel very nice. If men should live to home as we do out here, not much to eat, and nothing part of the time, hard bread and water the rest, then lay down in a puddle of water to sleep when you you could get a chance [and that wasn’t very often. For all that, I haven’t had cold feet first rate but I expect better times now. I hope that they will close this thing up pretty soon. Oh, if you could only see the property that has been destroyed in this war—cars blown up, engine stove up, provision strewn around.

Our new companies are down to Alexandria. They are coming up to join us now. They have found out where we are as one of the captains has been here. We haven’t had a chance to shoot our small guns at the rebs but we came pretty near if we had been nigh. We laid on a hill and the rebs was down across a hollow in the edge of the woods. They seen us on the hill and they put the shot and shell into us until Griffin’s Battery—the one that we was supporting—opened on them. There was a squad of graybacks showed themselves out of the woods when our battery put some shell among them. They left quick, you better believe. They killed 4 out of our brigade and wounded several but none of our regiment. But the regiment on the right of ours. They have took some of our regiment prisoners what couldn’t keep up. All I can say is that we have been lucky. There is plenty of new recruits in these forts here but they belong to New Jersey.

The letter I got from you was dated August 24. I couldn’t have wrote today if I hadn’t got this paper. I will write as often as I can but I don’t expect that will be very often. Some of us will manage to keep you posted. I must close now so goodbye. I feel tired. I expect to have some sleep.

— A. Lane

Letter 13

[Beginning of letter is missing. It was written probably sometime during the last full week of September 1862 following the Battle of Antietam.]

…these new fellows are sick of it already. I was talking with some of the 20th Maine that came just as we left Washington. He said if he had his bounty with him, he would burn it up. I told him he would have a chance to spend his bounty—that is all the satisfaction they get out of us. That shuts them up. We tell them they are paid for it and they have got to do the fighting.

Calvin Pool don’t look so slick as the first time I saw him at Arlington Heights. N. Burnham looks tough as any of them. You say you expect they will draft. I hope they will. I hope they will draft Young Allen Smith and Charley Pool and some others I know of.

How is the second crop and apples? You didn’t say anything about them. How is Ivory? Is he warrish? How did George & Charles get clear from going? You tell them boys at home if they knew when they are taking comfort, they are now at home. Out here you don’t know where you are or where you are going or what you are going to have to eat, nor where you are going to lay at night. Turned out nights at all times. Get your sleep when you can and when you lay down to sleep, you can’t sleep much on the hard ground. You have to do our own cooking. I have got a quart dipper that I do all my cooking in—make coffe, boil potatoes, squash meat, beans.

The 5th Maine was in that fight Sunday night back at Middletown but Otis and them boys come out all right. I don’t know whether they was in the big fight back at Sharpsburg or not. I haven’t found out. I expect they was.

Bane and Sewall went on picket last night [and] haven’t come off yet. All the Rockport Boys are well. Our company is small now. All we have got is 54 now. They are all strewn about sick. Capt. Draper has resigned and gone home. Lieut. Rich has command of the company now.

Tell Mother that she needn’t worry about me if she don’t hear from me for some time for we are marching about so much that there ain’t no chance to write and if there was, there [ain’t] no chance to send it. I will write as often as I can. I should think some of you would write as often as every Sunday. I get a letter about once a month.

We have just drawn some fresh beef. I am going to have some for supper. I wish I had a piece of your short cake too. I must close now. Give my love to all the folks. Write soon. We have got three months pay due. — A. Lane

Letter 14

Warrenton, Virginia

November 15, 1862

Dear Parents,

I write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and the rest of the boys are [too]. Since I wrote to you last, we have been on a march. We left Sharpsburg the 30th October. We came here last Sunday. Have been here a week. When we was at White Plains, we had a snowstorm. Since we have been here, we have been reviewed by McClellan and by Porter. Burnside [now] has command of the Army and Hooker has the Corps that Porter used to. So we are in Hooker’s Corps now. We are waiting here for clothes. The cars run here to Warrenton.

I received your letter & paper and the other bundle yesterday. I was glad of them. I don’t think we shall be paid off until January for I see by the papers that there ain’t no money in the Treasury. We haven’t seen anything of the rebs this time. The advance had a little skirmish with them at Snicker’s Gap. We held that Gap two days, They say the rebs are at Culpeper. I don’t know where we are a going. Some think we shall go to Richmond but I don’t know nor anybody else.

I must close now for the mail is going out now. I guess you had better send some money. Give my love to all the folks. From your son, — Andrew Lane

Letter 15

Camp of Potomac Creek about 5 miles from Fredericksburg, Va.

November 28, 1862

Dear Parents,

I take this time to write a few lines to let you know that I am well and hope you all are the same. Yesterday was Thanksgiving—the driest one I ever saw. We have been laying here a week now and our supply train hasn’t got up with us until last night so all we have had for six days was 14 hard bread. The day before Thanksgiving we had a half cracker dealt out to us. So I turned out Thanksgiving morning with nothing to eat. All we had the day before a half hard bread so I didn’t have no breakfast. So we waited [and] expected it would be here every moment but dinner time came—nothing to eat. The regiment was almost starved. You could hear the regiments holler “Hardtack!” all around but there wasn’t any to be had. So just at supper time the train came up. We had 15 given us apiece and some fresh meat and coffee. So we made out to have some supper. That was the hungriest I ever was in my life. All we had was one day’s grub in six.

I and [Joseph] Wingood is in one tent together. He had money but couldn’t buy anything. There is a large army here with us. We ain’t reserve now. We are in the 3rd Army Corps in the middle so if there is any fighting to be done now, we shall have to go in. As we have got Hooker for a leader and he is a fighting man, I feel tip top. I have got [as] good health as I ever had and look as well, so they tell me, but there is a great many sick. There was a fellow in our company died last night—Henry Pew, Jr. of Gloucester—with the chronic diarrhea. It is pretty tough laying around on the frosty ground. There is two fellows over here from the 35th Regiment—one of them I know [named] Sol Grimes. He says they lay about two miles from here. Wingood has gone over to see Burnham and the rest of the boys.

I received your bundle last night and was very glad of it. In two days more, we shall have 5 months pay due us. One year ago yesterday I enlisted. I hope they will settle this thing up so I shall be free once more. You won’t catch me into another scrape like this, I’ll bet you. I thought when I enlisted it would be settled up before this time, but I can’t see any prospect of its closing now.

Our mail has just come and one of our fellows has just handed me three letters. I am glad to hear that you are all well. We have had heavy rains here. The roads are hub deep with mud but yesterday was as pleasant a day as I ever saw. We are close to Aquia Creek where we landed when we came from Harrison’s Landing. We have traveled this road over three times. All the Rockport Boys are well. Give my love to all the folks. Write often. Accept this, — A. Lane, Jr.

They have just got the cars running from Aquia Creek now.

Letter 16

[Note: At some point in time, someone attempted to darken the ink of the handwriting and actually made it slightly more difficult to decipher the words and names. Contains a description of the Battle of Fredericksburg.]

Camped in our old camp about 3 miles from Fredericksburg

December 19th 1862

Brother Leverett,

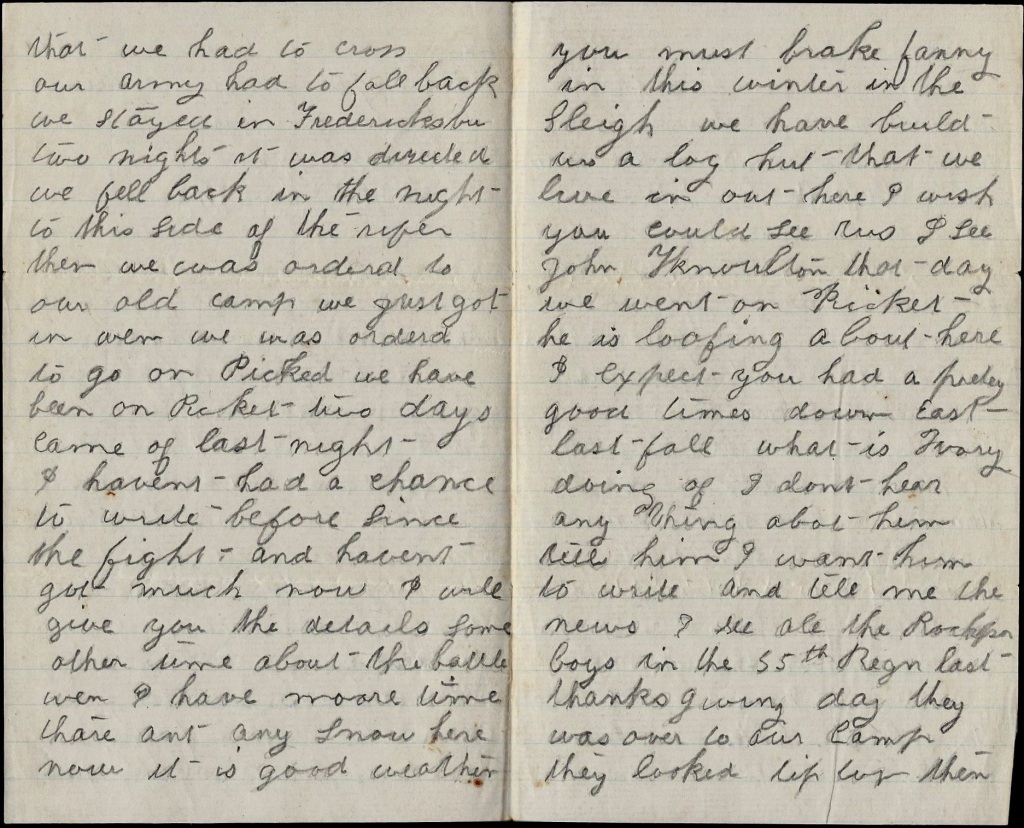

I received your letter last night and was glad to hear from you. We are all well. We have been in a tough old fight, I tell tell. But the Rockport boys come out all safe. We did not have any killed in our company. We had five men wounded. Our regiment went up on the charge bayonet. The rebels are on a hill entrenched and they can’t be drove out very easy as there is a clear field in front of them for half mile that we had to cross. 1

Our army had to fall back. We stayed in Fredericksburg two nights. It was directed we fell back in the night to this side of the river. Then we was ordered to our old camp. We just got in when we was ordered to go on picket. We have been on picket two days. Come off last night. I haven’t had a chance to write before since the fight and haven’t got much [time] now. I will give you the details some other time about the battle when I have more time. 2

There ain’t any snow here now. It is good weather. You must break Fanny in this winter in the sleigh.

We have build us a log hut that we live in out here. I wish you could see us. I see John Knowlton that day we went on picket. He is loafing about here. I expect you had pretty good times down East last fall. What is Ivory doing? I don’t hear anything about him. Tell him I want him to write and tell me the news. I see all the Rockport boys in the 55th Regiment last Thanksgiving Day. They was over to our camp. They looked tip top then. They was in this fight and I haven’t heard how they come out. Scraper [?] said that Crofert [?] Holbrook was wounded. Bane [?] just told me that he was over there yesterday afternoon and the Rockport boys—part of them—was left behind on guard.

You ask father to inquire of the expressman if there is any sight to get a box out here. If there is, to send me one. I want a pair of boots & some shirts. Our sutler has got boots but he asks $8 dollars for them. I heard that boxes were put through now. If that is so, I want one. I want some sugar & tea and something to eat. The mail is going so I must close now. — A. Lane

1 From the regimental history: “We recall the terrific accession to the roar of battle with which the enemy welcomed each brigade before us as it left the cover of the cut, and with which at last it welcomed us. We remember the rush across that open field where, in ten minutes, every tenth man was killed or wounded, and where Marshall Davis, carrying the flag, was, for those minutes, the fastest traveller in the line; and the Colonel wondering, calls to mind the fact that he saw men in the midst of the severest fire, stoop to pick the leaves of cabbages as they swept along. We remember how, coming up with the 62d Pennsylvania of our brigade, their ammunition exhausted and the men lying flat on the earth for protection, our men, proudly disdaining cover, stood every man erect and with steady file-firing kept the rebels down behind the cover of their stone wall, and held the position until nightfall. And it was a pleasant consequence to this that the men of the gallant 62d, who had before been almost foes, were ever after our fast friends. Night closed upon a bloody field. A battle of which there seems to have been no plan, had been fought with no strategic result. The line of the rebel infantry at the stone wall in our front was precisely where it was in the morning. We were not forty yards from it, shielded only by a slight roll of the land from the fire of their riflemen, and so close to their batteries on the higher land that the guns could not be depressed to bear on us. At night our pickets were within ten yards of the enemy. Here we passed the night, sleeping, if at all, in the mud, and literally on our arms. Happily for all, and especially for the wounded, the night was warm. In the night our supply of ammunition was replenished, and toward morning orders were received not to recommence the action.”

2 The 32nd Massachusetts was brigaded with the 4th Michigan Infantry and a few years ago I helped my friend George Wilkinson create a website entitled, Crossing Hell on a Wooden Bridge to showcase his large collection of 4th Michigan letters and diaries. One of the letters in this collection written by the Major of the 4th Michigan describes the movement of the battalion at the Battle of Fredericksburg in which both the 4th Michigan and 32nd Massachusetts were a part:

“About 1 p.m. the order came for our division to fall in. In a few minutes we were ready. Our regiment led — Lieut. Col. G. W. Lombard commanding — and in less time than I can write it, we were on our way. We hastily crossed the bridge, while our batteries on the hills this side of the river, threw shot and shell over our heads that screamed through the air like so many demons. But on we pressed, following our gallant leader, until we reached the main street running parallel with the enemy’s front. As we turned from this down the street leading to the front, their artillery — previously planted — opened upon us, and it seemed as though we were to be annihilated there. But it was of no use, on we went, following our brave Colonel (J. B. Sweitzer, as brave a man and officer as ever drew a blade or pulled a trigger), commanding our brigade, and our gallant Lieut. Colonel following closely upon him, with sword waving high over his head, cheering us forward.

But the brave 4th, taking a double quick and with a cheer, rushed forward with the spirit and enthusiasm which they only can do, hardly needing the encouragements which their officers gave them. Close behind came the brave and heroic 9th Massachusetts, and they followed by the 32nd Massachusetts, while the brave New York 14th, commanded by Lieut. Col. Davis — and for the last 18 months we have fought beside — brought up the rear. To march down those streets was like walking into the jaws of death. Shot, shell and bullets came crashing through our ranks, but not a man flinched but pressed forward, eager to get to the front where they might revenge themselves upon the enemy. We filed to the right around an old brick yard and proceeded to the extreme right, where we unslung our knapsacks and everything else that might impede our progress. And then, filling our canteens from a brook that was running near, we lay on our faces to escape the storm of lead that was hurled against us.

After resting for a few minutes, our colonel asked permission of our brigade commander to advance, but he wanted us to wait a few minutes. He asked him three times and the last time, in going to him, one of the 118th Pennsylvania, thinking he was going to leave us, drew his piece to shoot him. But before he had time to think, the soldier was seized by a squad of our men, disarmed, and I fear would have suffered for his folly only for the interference of our officers.. The order was then given to load. Every ball was rammed carefully home, guns capped, and we stood ready for the order forward.

About this time, General Humphrey led in his division in person accompanied by his entire staff, and bravely did they advance while the brave fellows fell by scores in almost every rod of the road. The sight was horrible and one I hope I may never see again. But — brave fellows — on they marched, bearing their breasts to the leaden hail that was poured into them. We moved our brigade to the left again and on the center. In a few minutes, all being ready, our brave Sweitzer, accompanied by his aids, Lieut. Cunningham, Plunket and Yates — as brave young officers as the world ever saw, and all [of] them mounted — rode to our front. The brigade lay at the feet of a small hill but not low enough to protect them, unless by lying down. We had to rise this little ascent, then cross an open space, but slightly ascending for some 25 or 50 rods. Then there was a small mound, as such as one as they build their fences on in Virginia, and the enemy some 30 rods from that protected by a strong stone wall, while the hills beyond were covered by their cannon. This open space the rebels swept with shot, shell, and cannister, while the musketry seemed almost to sweep everything before it.

As Col. Sweitzer rode to our front, and saw the energy and determination that was depicted on the countenances of his brave command, he took off his cap and waving it high above his head, in his clear and distinct voice, gave the command, “2nd brigade, forward — double quick — march.” With a cheer, we started — the brigade commander taking the lead. As we reached the crest of the hill, the leaden and iron hail was awful, and many a brave man fell. But quickly closing up our broken ranks, we marched into that terrible fire, and in a few minutes reached the little mound earth — fell behind it upon our faces — to escape the terrible fire we were exposed to. Our officers were everywhere, where their duty called them, and encouraged everyone by their own example. In a short time we were ordered to relieve the regiment on our front. As they fell back, our men took their places, and we opened fire on the enemy. And the men were ordered to keep down as much as they could. But as they became more and more excited they would get up and take deliberate aim as though they were shooting squirrel.

I was acting as Lieutenant Colonel, and had charge of the right wing. Captain Jeffords, of Company C, was acting Major, and had the left wing, while our brave and gallant Lieutenant Colonel had the center, commanding the whole. I cannot speak too highly of him — this being his first effort in taking the regiment into battle under his immediate command. But by his cool bravery and heroic bearing, he won the admiration of all — both officers and men — and the 4th need have no fears while under his command. He had established a name as a military man that will always follow him. And Captain Jeffords, although young in years, the prospect before him, if his life is spared, will be the envy of men older in military science and arts of war than he is. He is all we can wish for. Brave to a fault — cool in battle, he too is one of our favorites and the one that the boys will stick to.

The line officers all were heroes. Captains French, Hall, Lamson, Parsons, McLean, and Loveland. Lieut. Allen, commanding company G; Lieuts. Robinson, Gilbert, Vreeland, Gruner, Theil, Bancroft, and Rogers — all were everywhere where duty called them and acted nobly. But what shall I say of our lamented Adjutant, James Clark. But lately promoted to a Lieutenancy in the regiment and Adjutant of the regiment in full, and this being the first engagement he had been in as a commissioned officer, he was everywhere present, and by his cheerful voice encouraging his comrades on. He was the personification of heroic daring and cool bravery. After the action became general he came up on the right to company D of which he used to be a member, and smiling to his comrades and associates, says, “Boys keep your front ranks filled,” Sergeant Chester Comstock was between him and me. One of the boys told him to keep down, or so he would be hit. The words were hardly out of his mouth when a musket ball struck poor Jimmy on the third button of his overcoat, glanced to the left and went directly through him. He fell over toward where I was lying, and with a smile upon his countenance, he yielded up his young life without a struggle or a groan. I detailed four men from Company D to carry him to the rear, and put a guard over him, to protect his body from the robbers that follow in the wake of an army for no other purpose that to pillage the dead. Brave boy, although dead to us, your memory will live in our breasts. Kind and affectionate, to all, and by his gentlemanly ways he had won the respect and admiration of the whole regiment. I wish I had the pen to write his eulogy, but it is written in the hearts of all who knew him.

And what shall I say of Fred Wildt? He too, was instantly killed — shot nearly in the same place that poor Jimmy was. He was First Corporal in Company D, and one of the best and neatest soldiers in the regiment, ever ready to do his duty, which was always done cheerfully and willingly, and one who kept the neatest and cleanest equipments in the company. Brave boy! He too, has yielded up his young life upon his country’s altar. He too was carried to the rear and today Fred Wildt and James Clark lie side by side in Fredericksburg. Captain J. W. Hall, with the company and Chaplain of the regiment, Rev. Mr. Seage, buried them on a pretty little knoll in separate coffins, making their graves with a carved head board in order to find them again if necessary. Sleep on, brave soldiers and comrades, and while we who are left to fight our battles will revenge your death, sad hearts will be at home. Fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters will mourn your loss. But it will be consoling to them to know that they died brave and facing the enemy. How will this end? Am I not to lose all these brave and patriotic young men of Ann Arbor who left with me one year ago last May? I hope not. But it seems as though fate was against me. John Fisher was slightly wounded, but will be around in a short time. These are all the casualties in Company D. All the rest are here and well. I wish I could make mention of all this company, but suffice it to say they all did bravely. At last, night closed the scene, and the tired hosts of either army laid down and slept almost within hearing distance. The living laid down with the dead, and thus they slept. All night long could the groans of the poor wounded and dying soldiers be heard, as he wore the weary hours away in pain. One poor fellow belonging to 28th New Jersey was shot through both hips, and his groans for help were heart-rending. Our orders were to hold the position at all hazards. We were almost entirely out of ammunition, but about 12 or 1 a.m., that came, and we filled up anew, so as to be ready in the morning to renew the contest.

Sunday morning at last dawned upon us. The rebels during the night had dug some pits for their sharp-shooters, and if one of our men showed his head a dozen bullets would be after him. And thus they lay all the Sabbath, targets for each others sharpshooters. On that evening the regiment was relieved and fell back to the city, where they remained until about 3 a.m. on Monday, when the Division recrossed the river, being the last of the Grand Army of the Potomac to leave Fredericksburg….” — Major John Randolph, 4th Michigan, December 17, 1862.

Letter 17

Same old camp 1

January 3rd 1863

Dear Parents,

I received your letters and paper last night and was glad to hear from home. I am well and so are the Rockport boys. We have just had a hard march. The orders came in camp Tuesday noon for us to have three days rations and be ready to march in an hour’s time. So we packed up and got our rations and started. We couldn’t imagine where we were a going as the army was not on the move—only two of our brigades. One other division was with us. We started on the road leading to Warrenton. We marched until 10 that night when we halted for the night in the field, having marched 20 miles since 1 o’clock. It rained and the roads were muddy and bad. As it was my misfortune, I had to go on guard so I did not get any sleep. We were not allowed to kindle any fire. We had to go without our coffee.

We started at daylight and advanced 10 miles to Morristown without seeing the enemy as as part of our party had took another road and come here and had seen nothing, we were ordered back. It now being 12 o’clock and we being 30 miles from camp, we started. It began to snow and we thought we were going to have a storm. We reached our old camp at 7 o’clock having traveled 30 miles in 7 hours—the most we ever done, but we were pretty well used up when we got there.

(Heritage Auctions)

Our Colonel [Francis Parker] has resigned and gone home. The Lieut. Colonel [George L. Prescott] has command and a bully man he is too. He says, “Now boys, I want you all to try and get in camp tonight for I am going to muster you for pay in the morning and you shall have your whiskey after you get in,” and he done all he agreed to. There was some of the boys gave out [and] he let them ride his horse and he carried their gun for them. That is more the Colonel ever done.

The object of our expedition was to capture Stewart’s Cavalry as they say about 20,000 had crossed a ford but as we did not see anything of them, I guess they had recrossed again. And as we was out, I heard that they had made a dash to Alexandria and captured two of our regiment and killed a lot of our cavalry and captured a lot of our wagon train enroute for Centreville.

You wanted that I should state how bad I was off. I ain’t very bad off. I have got 2 shirts. Them I have on. The shirts that we draw are those white cotton shirts. The shoes are poor for they [are] nothing [but] old rags.

1 “After the disastrous attempt upon the heights of Fredericksburg, the Regiment had remained in their old camping-ground near Stoneman’s Switch, in the neighborhood of Falmouth. Excepting the reconnoissance to Morrisville and skirmish there, with that terrible march on the return when our brigadier, Schweitzer, led his “greyhounds,” as he termed them, at such a terrific pace for twenty-five or thirty miles, nothing occurred to break the monotony of camp life. The night of the 31st December, 1862—that of the march above alluded to—was extremely cold, and the men, in light marching order, without knapsacks or necessary blankets, compelled to fall out from inability to keep the pace, suffered terribly from exposure, and many lost their lives in consequence.” [The Story of the 32nd Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry, by Francis J. Parker, Colonel]

Letter 18

[Contains a good description of Burnside’s Mud March]

Camped in our old camp

January 25, 1863

Dear Parents,

I thought I would write you a few lines to let you know that I am well. I received your letter last week stating that there was a box about to start. I haven’t received it yet.

We had marching orders last Friday but did not start until Tuesday. We left camp Tuesday afternoon and marched about a mile and a half and camped for the night. It came up a rain storm. Rained all night. The next morning we started with mud over our shoes. We marched about 4 miles then camped and there we stayed until last night. We came back to our old camp. It has stormed all the time we have been gone.

We was to try a flank movement but Burnsides got stuck in the mud. Our brigade and others left our guns and went to work and cut trees and logged the road all the way so as to get our artillery back for they was stuck. They had to have 12 horses on a piece. We carried all the fences that the farmers had to make roads of. You would laugh to see them march a brigade up to a fence, then charge on every man with a rail on his back. I tell you, they take down the fences. It ain’t no use to tell about moving for they can’t.

Yesterday we signed the pay rolls for 4 months pay [to be] paid off tomorrow, I expect. The fellows say that there is a lot of boxes down to the depot. We shall get them soon. I didn’t take no peace on this last march thinking about them boots going over my shoes every step. When we got back, somebody had carried our house off and we have got to go to work and make another. I am on Police today. Been cutting wood for the officers. I expect today is Sunday but I shouldn’t know as it was.

I should like to see J. Graham just now. I expect he will be here today or tomorrow. The Rockford boys are well and anxious for their boxes. I must close now for they are after me to work. I will write again soon as I get the box. Accept this from your son, — Andrew Lane

Letter 19

Camped in old camp

January 28, [1863]

Dear Parents,

I take this time to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well. Mr. Marshall arrived here on Monday afternoon but his boxes were down to Falmouth but he went up to our headquarters and saw our Major and he started a six mule team off after them and they came about dark. We was building our house that afternoon so we just got her up that night in time. I gave him an invitation to stop with me which he accepted. He stopped here until about 9 o’clock when he and Cobson went over the the 35th. We was paid off Sunday night. Four months pay [or] 32 dollars, so we had a good chance to send it home by him. He took money for most everyone in our company. I had a fifty dollar bill so I gave him that to take home so if I get out, I shall send home.

I opened the box and found everything good in it and enough of it. I tried on the boots. They fit tip top. Yesterday I went down to the brook and had a good wash. Then stripped off my old shirts and socks, drawers, and put on new ones from head to foot. I feel like a new fellow. I think I shall gain a streak off of this box. That kettle is just the thing. When you nailed the box up, you drove a nail and it went through the side but I can stop that I guess.

You tell Susan that I tried her cake first one. It went good. Her molasses drops I haven’t tried yet. You return my thanks and best wishes to Mrs. Henigher for her cake. The same to Mrs. Smith for her cake and tea. I had a pot of her tea last night for supper. It was very nice. Tell Aunt Margret that the fish halibut is the best I ever tasted. Everything in th box was nice and just what I wanted. To mother and Susan, tell them they shall have a new dress when I get home and I expect to one of these days if nothing happens. It rained all night last night. It is snowing now today so it is nasty enough around here.

Oh, them stockings knocks all. I put on that long legged pair and they feel like stockings. My legs use to feel cold with them short legs on and no pants on. I guess I can stand it now.

We can’t move very soon now for it is storming and the mud is up to our ankles anywhere here. They say here that we are going to shift camp ground nearer to wood. I hope not now we have got our house built. There ain’t but two of us in it now. Yesterday Wingood went off on provist Guard over to General Griffin. If they like him over there and he does his duty, he won’t come back to the regiment again. It is a good berth—don’t have to go into any fights & get used better than we do. All they have to do is to go out on patrol twice a day and pick up stragglers that is out of camp. He is got a good place. I must close now.

So goodbye, — Andrew Lane

Letter 20

Camp near Falmouth, Virginia

February 14, 1863

Dear Parents,

I received your welcome letter tonight and was glad to hear that you were all well. I am well and the rest of the boys are the same. There is two hundred men detailed out of each regiment in our brigade. They went last Monday. They have gone, as I understand, about fifteen miles from here to a place called U. S. Ford. They [say] that our pontoons was left out there when we got stuck in the mud and they are building a road to get them back. I have been to work over to Gen. Switzer’s Headquarters building him a log house and a stable. He is home on a furlough and is going to bring out his wife when he comes back.

I don’t know what to think about our staying here. The Army is all leaving here. The 9th Corps has gone. I see a train start today loaded going down to Aquia Creek to take transports. They were ordered to report at Fort Monroe. They have been going now for ten days. The 33rd [Mass.] left about a week ago. Sigel’s Corps is going too. I think that they will all but this center division and they will either stop here and hold this place, or evacuate itor go nigher Washington. This thing is kept still for I don’t see anything about it in the papers. They are going up the Peninsula or to North Carolina. It is hard telling wher they are going to but time will tell.

Our Colonel is home on a furlough. They grant furloughs to privates [now]. There is one gone from our company to Gloucester. His name is James Murphy. He stops at Barnard Stanwoods when he is at home. There was two out of our company discharged the other day—Isaac Manwood and Carliss Stanwood [who] lives at Rockport. I heard that the high school gave an exhibition and tableaux. One of the tableaux was the boys in the 32nd Regiment receiving their boxes, some of them eating apples, one with a piece of salt fish, another trying on his boots. I should like to see the performance.

I heard that Ivory was down on the long beach hauling seaweed. He thought that was tougher than it was standing guard out here. Tell him I would like to swap with and let him try and see when it rains. He has somewhere to to go for shelter but out here he would find none. He would have to stand it wet or cold and lay down in the water that would come up to his hips.

There was five fellows came and joined the company [who have] been off sick. I don’t know those fellows that you told of in your letter. The weather out here is fine—warm for winter. The fellow in the tent with me had a ox come this week and has another on the way. I received a letter from Leverett last night which I will answer soon. I wish you had the oak timber that has been cut out here for fire.

Last Sunday I had them beans bakes for breakfast. They was nice. I baked them in the fireplace. They feed us better now [that] Hooker is in command than they used to. My rations of candles is about burnt out so I must close. Write often. Write all the news. From your son, — Andrew Lane

Letter 21

Camped near Falmouth, Virginia

March 7th [1863]

Dear Parents,

I received your welcome letter yesterday and was glad to hear that you was well as I am and the rest of the boys are. Capt. Rich came back last night. I haven’t seen him yet to speak to him. Our brigade has been on picket this week. They came in yesterday. I didn’t go for I was on guard over to General Headquarters the morning they went. I don’t know of any news to write. The furloughs of this regiment is stopped for the present. Our Colonel is under arrest for breaking his furlough. So is the Major. A captain has command now. They say this regiment is disgraced and I think it is.

I received a letter last night from George Simpson. He says the folks are all well. He says that they are going to draft down there. He says that the won’t stand it. He says there will be war at home. All the folks say so. Some of these folks would look pretty [sorry] if we had to be called home to put down a war. I am glad that law has passed. It serves them all right. I want to see everybody come and whip this thing out. There ain’t no use in keeping us out here three years. I want to see this thing put through. Then go home. I hope that some of them fellows I know of in Rockport will have to come. They have been blowing long enough. Let them come out and try it. I hear that they can’t hire no substitutes. They have to come themselves. It is raining here today. That fellow that is in the tent with me—his name is Charles Parsons. He belongs to Manchester. He is about my age. He has a carpenter’s trade. He is a pretty good boy. We was mustered the first of the month for pay but I don’t think we shall be paid very soon. If we don’t, I shall want a little money.

Tell sister I have eat them molasses drops. They were very nice. Tell her to be a good girl and keep the the dishes clean. It is all dull times here now. I don’t know of anything to write now. I will try and write more next time. I must close now and get ready for inspection. So goodbye. Write soon. From your son, — Andrew Lane

Letter 22

Camp near Falmouth, Virginia

April 10, 1863

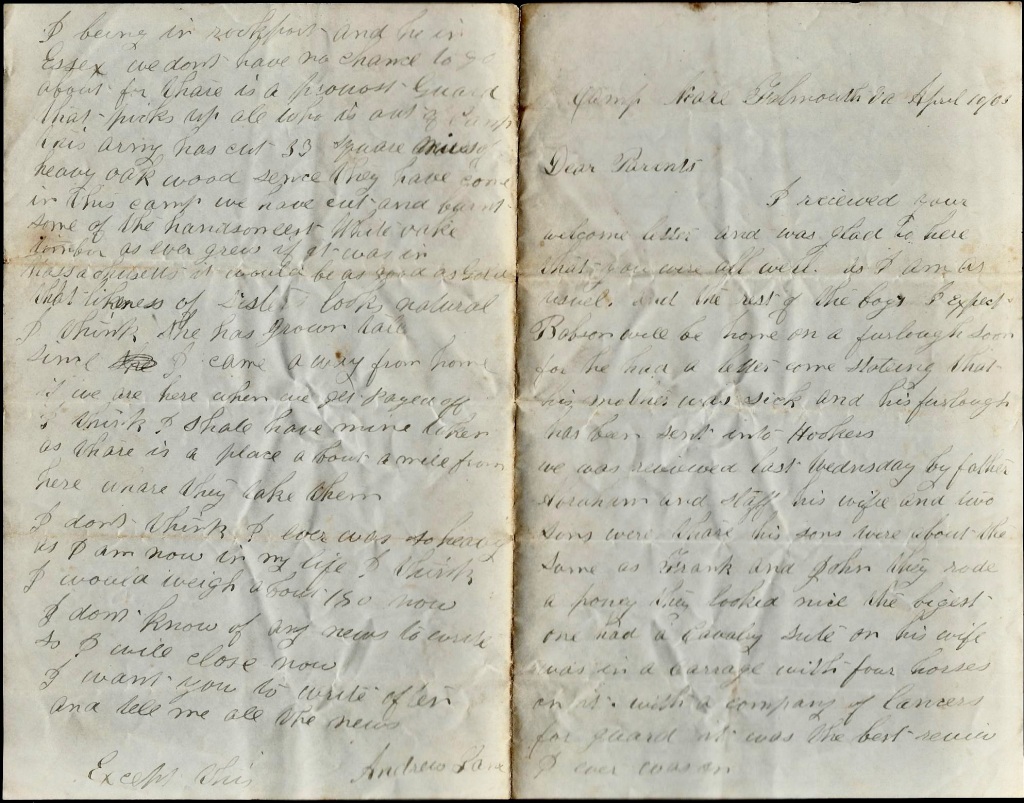

Dear Parents,

I received your welcome letter and was glad to hear that you were all well as I am, as usual, and the rest of the boys. I expect [Sylvanus B.] Babson will be home on a furlough soon for he had a letter come stating that his mother was sick and his furlough has been sent into Hooker’s [headquarters].

We was reviewed last Wednesday [8th] by Father Abraham and staff, his wife, and two sons were there. His sons were about the same as Frank and John. They rode a pony. They looked nice. The biggest one had a cavalry suit on. His wife was in a carriage with four horses on it with a company of lancers for guard. It was the best review I ever was on. He had acres of staff and guard with him. Them are regular government suckers. Old Abe looks rather poor. He don’t look as well as he did at Harrison’s Landing. He looks pale now. 1

The weather is pleasant and the roads are getting dry. I expect every day when we will move but I don’t see anything that looks like it yet. Where we went on review, we could look over to Fredericksburg [and] could see the rebel camps, enough of them, and could see their fires in the woods.

Solomon Pool was over here to see me about three weeks ago. He looks about the same as ever. He says he is third sergeant and is on the staff of the 1st Army Corps General but I don’t believe it the same time for he didn’t look so to me for he didn’t have hist stripes on and he wasn’t dressed up enough to be on a General’s staff for they have to look pretty well. Besides he had an old plug for a horse. Stephen Perkins and Henry Ferrel that used to drive team for Preston was over here to see [me] the other day from the 5th Maine. They are in camp at Belle Plains about ten miles from here.

We haven’t been paid off yet and I don’t know when we shall be. The last of this month we shall have six months due.

You stated in your letter that if I would like to get acquainted [with] Underhill and E. Young [but] I don’t know of any New Hampshire Battery about here. If he ain’t in this Corps, I shouldn’t be no more likely to see him for this army covers a great many miles. It is about like me being in Rockport and he is in Essex. We don’t have no chance to go about for there is a Provost Guard that picks up all who is out of camp. This army has cut 33 square miles of heavy oak wood since they have come in this camp. We have cut and burnt some of the handsomest White Oak timber as ever grew. If it was in Massachusetts, it would be as good as gold.

That likeness of sister’s looks natural. I think she has grown tall since I came away from home. If we are here when we get paid off, I think I shall have mine taken as there is a place about a mile from here where they take them.

I don’t think I ever was do heavy as I am now in my life. I think I would weigh about 180 now. I don’t know of any news to write so I will close now. I want you to write often and tell me all the news. — Andrew Lane

Accept this.

1 Noah Brooks, journalist for a Washington paper wrote that President Lincoln reviewed “some sixty thousand men,” representing four infantry corps. Brooks accompanied Lincoln’s party, and recalled, “[I]t was a splendid sight to witness their grand martial array as they wound over hills and rolling ground, coming from miles around . . . The President expressed himself as delighted with the appearance of the soldiery . . . It was noticeable that the President merely touched his hat in return salute to the officers, but uncovered to the men in the ranks.” [The Lincoln Log]

Letter 23

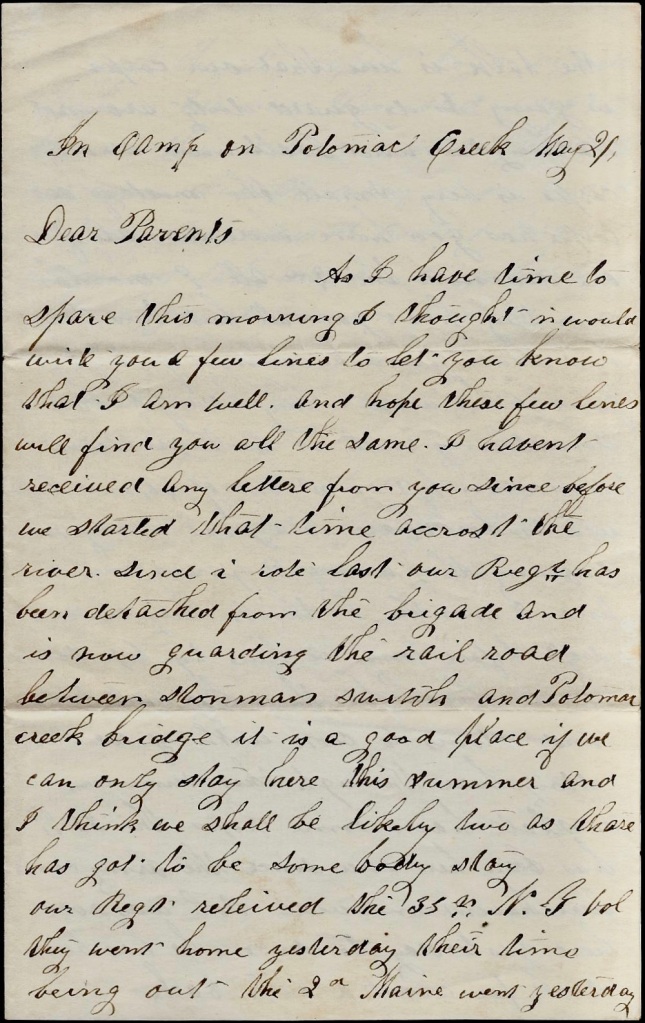

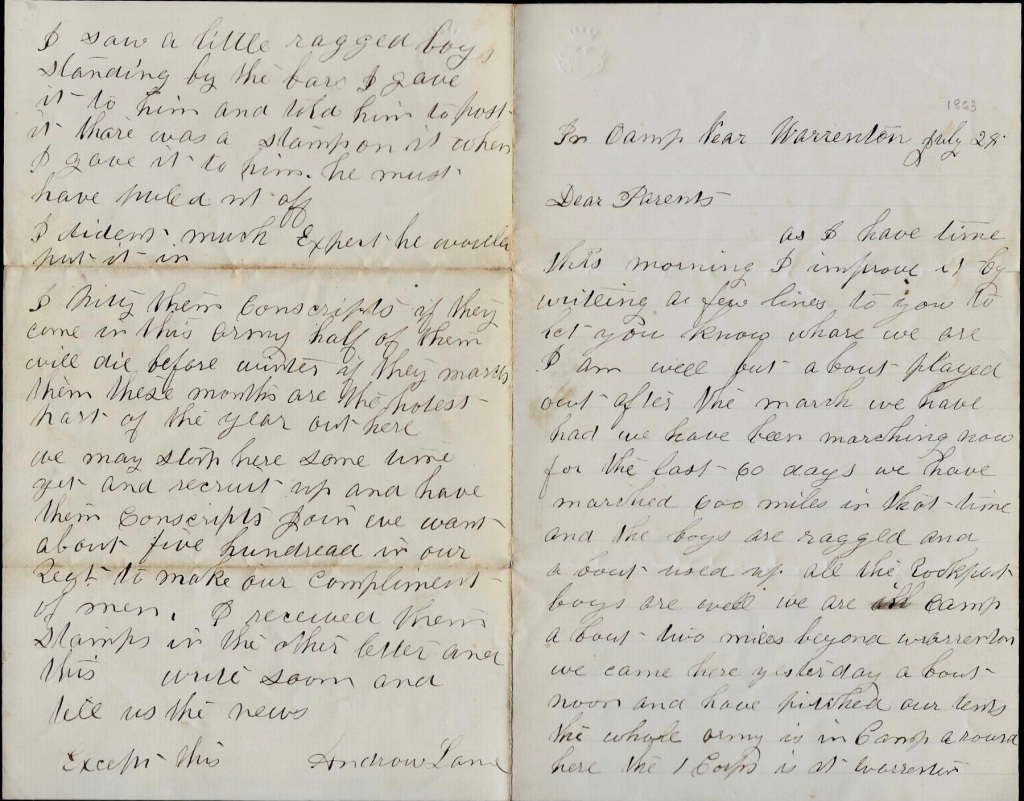

In camp near Falmouth [Virginia]

April 10, 1863

Dear Parents,