The following letters were written by Otis Whitney (1821-1901) who served in Co. H, 27th Iowa Infantry. The following biographical sketch summarizes his life very well.

(Iowa Civil War Images)

Otis Whitney, Jr., was born 13 Jun 1831, in the town of Seneca, Ontario County, state of New York, where he lived till nearly thirty years of age, working on the farm, attending school and studying law; was admitted to the practice in the supreme court of the state of New York at a general term of the court held in the city of Auburn, county of Cayuga, on the first day of November, 1847, but never engaged actively in practice, having no relish or respect for it. He traveled and taught school for three years, and then went into partnership with his brother-in-law, Tyler H. Abbey, who was a successful merchant at Watkins, Schuyler County, state of New York, and continued in business up to the fall of 1854, when he caught the western fever and decided to take the advice of Horace Greeley to “go west and grow up with the country.”

Before leaving he was united in marriage with the daughter of Dr. Enos Barnes, in western New York, a well known and popular physician and surgeon, and one of the earliest settlers on the west side of Seneca Lake. The newly married couple started immediately on the journey west, and finally located in Quasqueton, Buchanan County, state of Iowa, where he purchased two hundred acres of land, intending to make a farm of it, but finding more satisfactory employment in town never settled on the land. Most of the time up to 1862 was spent in clerking, overseeing flour and saw mills, and acting justice of the peace, for which office his previous study of law was especially helpful. In the fall of 1862 he went into the army as first lieutenant of Company H, Twenty-seventh Regiment Iowa Volunteer Infantry. In camp of instruction he was familiar with the drill, etc., as he had been studying the tactics from the commencement of the war and in command of and drilling a company of home guards for more than a year. In a few weeks the regiment was ordered to the field, or as the popular phrase is, to the front, and not more than half drilled or disciplined. On 10 Apr 1863, he became captain of the company by reason of resignation of Captain Jacob M. Miller, the previous captain, who became disabled and unable to endure active field service. Whitney was captain of the company up to the close of the war, and was discharged with the company and regiment at Clinton, IA, 8 Aug 1865.

He returned to his home in Quasqueton, which he had not seen in three years, worn out, run down, and weak from constant for three years, and which continued for more than fifteen years after the war. Finding no place of business obtainable he with his family, wife and two children, went on a visit to the old folks at home in the state of New York. While on this visit he was induced to engage in an enterprise to be consummated at Richmond, VA, in the establishment of a dairy farm. The project was a complete failure, and mindful still of the advice of Greeley he again went west with his family to grow up again, locating on government land in Oswego Township, Labette County, Kansas, in the spring of 1867. Upon this place he lived seventeen years, when he sold out and moved into the city of Oswego, two and a half miles distant.

[Note: These letters are from the private collection of Greg Herr and have been transcribed and published on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Letter 1

Camp Gilbert

6 miles above St. Paul

October 15, 1862

My dear wife,

It is now one hour past midnight of the 14th. I am in a room with eight others (one sick with a fever) trying to pass away the night. No beds in the room. The reason why I am here is because I happened to be chosen to act as one of the clerks of election which we held on the boat and came here to canvass the votes. Our camp is about half a mile above Fort Snelling. Our tent is up but no arrangements made for sleeping & the weather is so cold we did not like to occupy it tonight. Ice froze half an inch thick last night in pails that were sitting on the hurricane deck of the steamboat we four companies came up on.

We embarked Sunday morning & had a pleasant trip with some little adventure. Sunday night, just at dark, a snag (a large tree trunk) smashed through the guard deck near the bow of the boat & came very near throwing some of the boys overboard. A few minutes before there were several standing on the very spot where the crash was made. Last night a steamer coming down undertook for some unexplained reason to run our boat down but by the skill of our pilot, we avoided being struck but in doing so, the stern of the boat was thrown so near the shore that a tree on the shore crashed through the side of the boat & tore out the entire side of the barber shop to the great fright of several men who were sleeping on the floor & in chairs. The fright was not without cause as it came near sweeping off several men.

The affair I spoke about when I wrote Saturday night was more serious than I then supposed as you have probably learned by the papers before this time. We brought the corpse of the young man with us to McGregor’s Landing. It is hard to see stout young men killed in that way. It is feared the affair will not end so but that more blood will be spilt. Tomorrow 6 companies of our regiment are ordered north to guard the U S Paymaster in paying off the Chippewas their annuity. My company H remains here. 1 Some think we shall be called out to fight the Sioux. It is thought we shall be sent to Kentucky within three weeks.

You need not be alarmed at any stories you hear. I am now enjoying good health and shall probably live out my allotted time.

I got the comforter you sent & it was very acceptable. I ought not to write any more as I would like to sleep a little if I can on the floor. Kiss Emma & little Eddie for me. Much love to yourself. — O. Whitney

P. S. SEnd me the description of lots where the house stands. The deed is in the top part of the box you keep in the drawers. — O. W.

1 Companies “A,” “B,” “C,” “E,” “F” and “G.” Moved to Mille Lac’s, Minn. October 17, thence moved to Cairo, Ill., November 4. Companies “D,” “I,” “H” and “K” at Fort Snelling, Minn., till November 1. Moved to Cairo, Ill., November 1.

Letter 2

Camp Defiance

Cairo, Illinois

November 19th 1862

My Dear Wife,

I have just received your letters & all the articles. The socks are particularly acceptable as those I have on hand are getting the worse for wear.

I have not opened the can to see what is in it. The corn will be very good if I can get it cooked. That is the great difficulty in the way of enjoying any such thing that may be sent us. It is impossible to get any cooked unless it goes into the general mess. The bandages will be carefully preserved against time of need. I hope I shall have no occasion to use them.

You say you hope we will go into winter quarters here. If you could look around & see the position we occupy, you would soon change your mind. It would be difficult selecting as bad a place for quartering soldiers in the state of Iowa as this. It is mud everywhere and such mud as you do not see in Quasqueton. It sticks fast to ones boots until they are completely loaded down. But this is not the worst of our position. It is very unhealthy. Dr. Hastings is afraid there will not be well ones enough by Saturday night to take care of the sick.

Several of us officers occupy an old shanty on the top of the embankment that keeps the Mississippi and Ohio from overflowing the town in high water. The boys and many of the officers sleep on a level with the Mississippi in ordinary stage of water. The place, Cairo, is one of the most God-forsaken places it has ever been my misfortune to visit. Almost every place is a drinking saloon. The place boasts a theatre all on the ground floor. Steamboats and gunboats swarm.

Yesterday 750 secession prisoners embarked for Vicksburg to be exchanged—forlorn God-forsaken wretches—they breathe out blasphemy & threats against the Union.

My quarters are within six feet of one of the sentinels around the battery that defends Cairo. At daylight our quarters are shaken by the thunder of a great cannon.

The sick, wounded and crippled are all around us. War is a horrible thing. I had intended to close my letter with this page but as I have just heard a rumor that we are to go to Memphis soon, I will fill up the fourth page.Our regiment is in most miserable condition to meet the enemy. Poorly supplied with poor guns and many of them unfit for us. God have mercy on us if we have to go into battle in our present condition.

I thank Alice for her kindness with kind regards. Hand over to crooks all of Mt. Buell’s notes with orders to put them into Judgments after requesting payment. Also all other notes except mine. Take his receipt for them. Those charges of Elie’s are correct. Keep the piano. Take William’s word. I shall write to Father & Columbus today. Give my love and respects to Mr. Henry’s family. I will try and write often. Don’t send stamps.

With a kiss for Emma and Eddie, I bid you goodbye for the present. With much love, — Otis

P. S. It is not certain we go to Memphis. Direct to this place care of Col. Gilbert, 27th Regt. Iowa Vol.

Letter 3

State of Mississippi

November 29, 1862

My dear wife,

I write you a few lines upon a camp chest, my candlestick a bayonet stuck in the ground.

I am now about thirty-three miles from Memphis. The camp is on a great broad flat, mostly covered with timber. The locality of the 27th Iowa is in a cornfield together with several other regiments. Our whole force I do not know but probably not far from 40,000. It may be more & may be less. On three sides are hills, mostly covered with timber. The fourth side is a continuation of the flat, heavily timbered & inaccessible by a large force. Batteries are posted on the hills around.

Our march from Memphis was very tedious yet I endured it very well—much better that I expected. The first two days I was able to relieve the men by carrying their guns for them. The third day I had all I could do to get along myself well as I could. You may think it a small matter to march only 33 miles in three days but it was not so.

The first day we did not start until in the afternoon but was on foot all day. We reached camp about nine o’clock p.m. Pitched tents, got supper, and got to bed about midnight. The next morning was on the march before sunrise [and] encamped about sun down. Troops were arriving till 2 o’clock in the morning. The third day were up before daylight but did not march till nearly noon. Waiting, waiting, waiting—more tedious than marching. We reached this camp sometime after dark. We marched by a round about course so that we have actually come more than 33 miles.

The tedium of the march is partly owing to repeated halts—some not lasting a minute. I presume we were over an hour passing over the last mile. The men were mostly exhausted, some miserably footsore. Others were weak with sickness. I was troubled with both. Today we have lain in camp. Tomorrow morning we have to march at 7 o’clock without bag or baggage except what we can carry on our backs.

We have an object in view. That is to cut off Van Dorn and Price from forming a junction with Bragg. We look for a battle tomorrow or next day—a severe one. We have had pale cheeks in camp already. I do not intend to say anything to excite your fears. This may be the last letter I can write you & yet I may be spared to write many more & come home to stay for many happy years. God only knows.

It is very possible that Price may run too fast to be caught. If we do intercept him, we shall have a battle. If I survive or am able, I will write as soon as possible. If I go down, I commit you and the children to God & such friends as you can find. I intend writing a short letter home asking their sympathy in your behalf. I send you an order on P C. Wilcox from his nephew for ten dollars. My wages due from the government some $200, you may get after awhile. I cannot tell how now.

It grieved me to leave you in such straightened circumstances but it cannot be helped. I must not write more now. I need strength for te march. Forget and forgive my many failings since we have journeyed together. God bless you and Emma & Eddie. A kiss for them & much love for you. — Otis

Letter 4

State of Mississippi

December 6th 1862

My Dear Wife,

I have not heard from home since leaving Cairo & it is hard telling when letters will arrive. As usual we are in suspense & uncertain of our future movements. One thing, however, seems probably certain and that is that we are not very likely to have an action with Price’s forces for the present. I dare say you are glad of it & so am I, although I would try not to flinch from any duty. Price seems to be the prince of Generals at retreat & a middling good fighter when he can engage an enemy far inferior to him in numbers.

The cannonading I wrote you about was Gen. Grant shelling Price out of some fortifications on the Tallahatchie river about four miles from our present camp. Price evacuated in the night precipitously leaving sixteen of his heaviest guns spiked. His night retreat saved his army from being cut off ot our division from a defeat. We make no calculations for defeat & with an equal force numerically I think we need not. We expected to move some nine miles this morning but owing to a scarcity of provisions the march was postponed one day. So we march tomorrow or expect to on Sunday, of course. Almost all of our movements are begun on Sunday.

We are encamped in the woods on good dry ground & are very comfortable although deprived of many conveniences of home. You would be surprised to see the water we drink for common. It is about a good straw color, mostly caught in mud puddles. Sometimes the boys go to the river after water which is much better though highly colored with the yellow clay of the banks. It is no small job to go one and a half miles through clay mud after water. All our cooking is done with water except occasionally a fry. It is very difficult to cook rice, beans, mush, or anything of that kind without burning. Yesterday they commenced cooking a kettle of beans and had made great calculations on a cup of bean soup for breakfast but when I tasted, it was burnt & bitter with smoke & fire. I got hold of a piece of beef & roasted it on a stick.

The next move we make we may be situated where we can get sweet potatoes, sugar, and some chickens but a stay of two or three days exhausts the supply and then we come down to bare army rations which are how reduced to through greater rations & counting a 42 lb. box of crackers at 52 lb. I am feeling middling well though not strong. Night before last we had a visit from several of the boys in the Iowa 5th—Wm. Brown, Henry McWilliams among them. They are well & in good spirits.

I wish you would write me about the cistern, the house painting, and the floor in the shanty. The bills, &c.

The sergeant major was just here to notify us that we move in the morning at 7:30 for a place called Oxford 10 or 15 miles down the river. Our last camp was about a mile from a little place called Chulahoma. With a kiss for Emma and Eddie, as usual, yours with love, — Otis

P. S. Direct to Cairo, Illinois

Co. H, 27th Regt. Iowa Vols.

Letter 5

Holly Springs, Mississippi

December 23rd 1862

You see I am in the famous place called Holly Springs—a place I little expected to see when we passed it some 12 miles west in chase of Price. I have sent you two letters within ten days. As one or both have probably been taken & destroyed by the secessionists, I shall have to go back a little further than I would otherwise.

Our third camp before this was at Waterford from which place we moved down the railroad 5 or 6 miles on the Tallahatchie where we (the regiment) was divided up and posted along the railroad to guard it. My company and another was posted something like a mile above and towards Waterford & ordered to throw up breastworks which we endeavored to do with all alacrity & perseverance but before they were half completed, we obliged to leave under the following circumstances.

On Saturday morning (the 20th, I believe) report came into camp that Holly Springs was attacked and taken by the secesh and that a body of their cavalry were on the way to either attack us or pass nearby to destroy a bridge below us. We were accordingly hurried out of quarters with no baggage or provision to march some mile or two, resist the passage, and then return to stay over night. It was afternoon when we started. Reached the post, formed line of battle, stacked arms—built a great high rail fence 30 or 40 rods long (of old rails handy by) then took positions by companies & waited for the enemy. No enemy came, and after waiting two or three hours, word was received to march for Holly Springs by way of Waterfordm whole distance about 15 miles.

We trudged on for Waterford which we reached just at dark where we found troops pouring in by the wholesale. We camped—or rather lay out at Waterford over night, for our blankets & overcoats did not reach us until about 12 p.m.

Before going any further, I will go back & relate a little incident exhibiting the varied fortunes of war.

On Satirday morning at daylight, 14 secession cavalrymen rushed upon a hospital a mile from our camp, made prisoners of the guards—some 12 in number, took what horses they could find (among them Doctor Hasting’s horse) and left in a hurry. No one in our company had the misfortune to be taken. Doctor Hastings can owe his freedom to the comfortable habit of waiting for the sun to rise first. However, the boys are all paroled as we hear today—out of the service until exchanged.

On Sunday morning early we commenced the march for Holly Springs, nine miles distant, which we reached about 2 p.m. The rebels fled Saturday night after destroying immense army supplies, railroad cars, and burning some of the best blocks in the town. They also destroyed a heavy mail and ransacked the Post Office. They also took some 1000 [prisoners], most of who, they immediately paroled, not having time to parole all. Several were killed and wounded. We cannot learn how many. You can learn by the papers long before we shall know. That is the only way we have of learning what we have done,

Yesterday morning my company was called out for picket guard. Slept in the woods over night. Had my blankets so that I got along very comfortably. As Lieutenant, I stay at the reserve & can usually rest most of the night. Sleeping on the ground in fair weather is not so very bad after one gets used to it but in wet weather it is decidedly uncomfortable. Our future destination is not yet disclosed. Some say our tents and camp equippage will be brought to us tonight.

Holly Springs is a beautiful place of some 2,000 inhabitants. The beauty of the place consists mostly in the ornamental trees, evergreens, surpass anything I have ever seen in the North. They elicit the unbounded admiration of the boys. There are some very fine dwelling houses equal to anything we see at the North. The planters’ houses are generally off some distance from the road. Generally very comfortable and capacious, flanked on either hand by negro huts, also in the rear. The impression the boys get is that the planters live very well—in fact, much easier than northern farmers.

I can’t tell you anything more now. I am getting tired sitting on the ground leaning against the sharp end of a board. The boys have plundered all they could since coming to this place—against orders. Preserves, jelly, marmalade, and many fancy articles. I am writing with a splendid five dollar pen [made by] A. L. Shurtleff, found on paper jayhawked, all supported upon a splendid quorto quill & Morocco-bound volume entitled, National Portraits, 1836, also with ink that was not bought.

The boys seize many fancy articles of no earthly use to them and which they destroy or throw away when they march. Yesterday I went over the battlefield. The most noticeable feature was broken guns—broken purposely by the victorious party. The dead and wounded are out of sight. The newspaper paragraph recording the fight should be headed, Disgraceful Surrender at Holly Springs, or as Artemus Ward has it, “words to that effect.” There was criminal carelessness on the part of the commander of the post—or treachery.

I do not know when I can send this as our communication is cut off. If you have received the trunk I sent home, open it immediately and air the things. One of the boys gives me a paper of uncle’s to send home. Direct to Holly Springs.

Love to all, remembering the kiss for Emma and Eddie. Yours with love, — Otis

Letter 6

Jackson, Tennessee

January 10, 1863

My Dear Wife,

I have lately received 12 or 15 letters of yours so I concluded I have received all you have written. I have not written you for nearly or quite two weeks. You must not expect letters every two or three days as it is impossible for me to write so often. Today we may have nothing to do & so it may be for several days & then we may be put on a march for several days when it is utterly impossible to find time to write [even] if I had the material for writing.

The last few days of 1862 we were moving from one point to another until on the last day of the year at 2 o’clock a.m. we were landed at this place. Got two hours sleep before morning. After breakfast I lay down and slept two hours more when orders were received to change camp to another part of town. Camp was changed & we had fixed up a very comfortable bed with leaves. The boys being very tired and sleepy, went to bed early but not to sleep for at 7 p.m. orders were such that none took more than a canteen, haversack without plate, knife, or fork, and one blanket. Orders were left with the cooks to have breakfast ready for our return in the morning.

Daylight in the morning found us 14 miles distant on the road to Lexington and night (9 p.m.) found us 33 miles from our tails, bedding and provisions. Thus we spent the last night of the old year & new years day marching most of the time for 24 consecutive hours with 1 and a half hours stop for sleep & that in the open air without fires as they were forbidden to be built. You must not suppose it took 22 hours to march 33 miles. Marching is done by hitches and starts. The stopping is more tedious than marching unless the stop is long enough to allow of siting down. The marching is very different too from taking a walk down street. Everyone must carry a blanket & heavy overcoat besides his arms. A soldier’s weighs not far from 25 lbs. (a little more than a pail of water; the whole load more than two pails of water.) These overcoats and blankets when wet are very heavy.

The 2nd day of January at 4 a.m., up and at 5 on the march making 30 miles this day by 8 p.m. Fixed a comfortable bed of corn stalks & got nearly asleep at 12 p.m. when orders came for Company H to fall in & report at the General’s Headquarters. Did so, the captain too sick to go with the company. Gen. sent is with another company to check an expected attack. Just as we were falling into line to go to the General Headquarters, two volleys of musketry were heard out on the picket line we were going to guard. The firing was two companies of the 18th Illinois firing into each other—one company mistaking the other for rebels. The result was two killed on the spot, one mortally wounded, and nine others wounded. Before we reached our post, it commenced raining & continued most of the night. Our post was close by the road in a grove of cedar. The ambulances passing by us for the dead and dying & wounded. I got a little sleep on the rocks & did not get very wet. Were relieved a little after daylight. Returned to camp & got a little sleep.

About 10 a.m., cannonading was heard over on the Tennessee river and word was given to fall in. Now commenced one of the most serious marches we have yet had. The distance is 12 miles to a point on the river we wished to reach.

The soil is a miserable kind of clay—sometimes red, sometimes yellow, and sometimes a mixture of red and yellow, ochre, but in places ledges of rocks. The mud was indescribable, soft, slippery, sticky and deep, and yet under the excitement of the cannonade the soldiers, 3 regiments of infantry, our battery, and a part of a regiment of cavalry, made the march to within 2 and a half miles of the river in two hours, as near as it was safe for us to approach, the enemy having the advantage of us in cannon and position. Besides, they had effected a crossing & we could not get at them if we would. The cannonading was all on the rebel’s side. We now commenced a retreat for our position was one of great danger, exposing us to a surround in a position impossible to defend.

It was dark long before we reached our old encampment. Some of the men came in with one shote on, some bare foot, and some did not come in at all that night. Capt. Miller must have been 3/4 of an hour passing the last quarter quarter of a mile. So passed the 3rd day of the New Year.

The 4th, Sunday, we were permitted to lie in camp except to go through with battalion inspection. The 5th at daylight were on the way for as we supposed Jackson by way of Lexington. Made 18 miles. Rained in the night. Most got very wet. 6th at daylight on the march. Made 18 miles. Camped 3 or 4 miles from a place called Henderson on the Memphis and Corinth Railroad, 17 miles from Jackson. The march today very hard owing to blankets being wet & more gave out than usual.

7th, on the march before daylight and made Bethel on the Memphis & Corinth Railroad (32 miles from Jackson) at about 2 p.m. Were then marched to the railroad to take the cars for Jackson. Waited by the railroad track 3 or 4 hours before the cars came along. Reached Jackson about 11 p.m. safe and sound. Cars stopped by two girls who had extinguished a fire built by the rebels to throw the train off. Conductor gave the girls $5.

Boys are very glad to get back to their tents and cooking utensils. Some nights parts of companies would have to be up all night to cook mush enough to eat. Many had to leave in the morning without a breakfast.

9th, lay in camp undisturbed except to clean off camp ground. 10th, writing letters and battalion drill. So you see we have been pretty generally employed for the last 8 or ten days. Soldiers in the service 18 months say it was the hardest trip they have had.

You wish me to answer your questions, &c. Let Dr. Hastings’ account stand. There must be some mistake about it. Let Mr. Hyde, Mr. Alford, and all others wait till I get money & then if they have not done the fair thing, let them wait. I am sorry you wrote to Frank Smith. My charges were only made as a means of defense in case she should sue me on the note I signed which she holds against Ed….Do not trouble yourself to write more than once a week. With a kiss for Emma and Eddie, I remain yours with love, — O. Whitney

Letter 7

Camp Reed near Jackson, Tenn.

February 1st 1863

My Dear Wife,

I have just returned from picket duty & find a letter from you of the 25th together with the directions for making an allotment. I have seen the system before & had Mr. Lakin to explain the business. I did not think it worth while to make an arrangement to have any part of my wages sent home for the reason that no money will be sent only while or at the time we are paid & probably not until after the paymaster should make his returns to the War Department. We can probably find opportunities to send money home when we get it to send.

I find you are sometimes mislead by the papers as to our position, &c. I have already written you that we are under Col. Dunham acting as Brig. General, The brigade is made up on the 103rd Illinois, 50th Indiana, 1st Tennessee, and 27th Iowa. We are at present in Gen. Sullivan’s Division. Now that I think of it, I will say that you can shorten your direction of letters to me. Direct them to Cairo, Illinois, 27th Regt. Iowa Vols. Writing to the care of Col. Gilbert does not amount to anything. we are supposed to be still in Grant’s Army.

I wish you would send me F. N. Shurtleff’s letter as soon as possible. If it is what I have looked for, I am more than usually interested. I should like to hear from Ed again but I am afraid it will be some time first. I don’t know but he may be disappointed about the Thompson notes. I sent him two two notes I had taken up from which he could see the amounts, yet I am afraid he had the impression that I had taken up the large note that Thompson still holds against him and being so disappointed does not feel inclined to write me anymore. You know he owes me $100. It is very possible he would not have sent that if he had not supposed I was paying off the large note. I never gave him to understand or never intended to do so that I was paying or should undertake to pay it.

One thing is certain, if I ever return from this war, I must have better paying business than I have had in Quasqueton or my friends or the town will have to support us. I dare say there will be time to talk of these things hereafter if at all necessary to talk of them.

Our cook is hurrying up the supper and I must hurry out of the way. Our chaplain is now holding a meeting within ten rods but I shall not go to hear him. This is the second time I have known of his preaching.

You speak about my coming home as if you did not want me to come home until my time is out or the war closed. If that is the case, I am afraid I shall hardly come home again. You look upon this war differently from what the soldier does. He—or most—can see no end & but few feel able to endure the three years. As to seeing the hand of God on our side, I can’t. He may favor a great principle we may have in view but He must certainly abhor the principles of the men endeavoring to sustain that principle. I see no end unless a new policy is adopted. How will the North like another call next fall for 600,000 more?

I must go out to dress parade. Kiss the children for me. Affectionately yours, — O. Whitney

Letter 8

Camp Reed near Jackson, Tennessee

February 5th 1863

My dear wife,

As it is a stormy, snowy day 7 not much to do, I will improve the opportunity to write you a few lines, in other words & perhaps a less hackneyed expression—write you a short letter.

as you see, we are still in the old camp at Jackson and are making a long stay for the 27th [Iowa]. We have just experienced another Tennessee snow storm & it is now raining which may terminate in another snow. Residents and those familiar with the country say February and March are the winter months, If so, we shall probably yet be subject to considerable exposure and inconvenience from inclement weather.

Our military operations are now confined to camp guard and picket duty of which we have enough & to spare. Once in about four or five days the 27th furnishes from 300 to 350 men for picket duty. Picket duty runs like this. Our camp is some mile and a half north of town from which the guard formed in line march to Gen. Lawler’s Headquarters in town where the guard is detailed in squads of from ten to twenty, each squad with a commissioned officer and are stationed on the several roads leading into town. These squads are posted out on these several roads from a mile and a half to two and a half miles out of town. The quad is posted at some convenient place to observe the road outwards & have to keep posted on the lookout from one to five, who are relieved every two hours, ready to give the alarm if the enemy should appear. They have to examine papers and take them up of persons leaving town and make those coming in show their oath of allegiance. In the night, none but soldiers are allowed to pass out or in on giving the countersign. Citizens with the countersign are to be arrested and handed over to headquarters in the morning. The regular time for picket is 24 hours but they cannot leave the station until relieved if it is nor in a week or more.

On most of the picket stations there is a rude shelter, or some the “heavens with a blanket for a cover.” The most disagreeable part of standing picket is in the probability that in case of an attack, the picket will be either shot or taken prisoners. There is one consolation—that the enemy will not come in on more than two or three of the ten or a dozen roads leading into town.

Co. H is not called upon to furnish very heavy guards for the very good reason that we have only 18 men reported fit for duty. Yesterday we had 35 men reported sick. today we have 38. The addition consisted of the orderly Wilcox, Charles Coulson, & Jim Haskin. The orderly cut his foot (not very bad) with an ax. Jim said he had the cramp colic through the night. Charles Coulson had the ball of his thumb cut with a butcher knife. Day before yesterday the Captain [Jacob M. Miller] went to the hospital in town. He has done nothing but give orders in the tent since returning from the Tennessee Expedition. [William G.] Donnan has been with Col. Dunham of late—will probably stay there.

Day before yesterday morning, five companies were sent by rail to Henderson 18 miles toward Corinth to forage, &c. At present we are without the prospect of an immediate change & yet the change may come all the sooner. If there is any move, I must lead the company. I don’t like the way things go. Capt. M[iller] is considered by the men a wonderful good man while for myself, I don’t think I am very well liked. Difference. Capt. M[iller] has never been on battalion drill but two or three times, has not drilled the company an hour, & has been away from it nearly half the time. [Lt. William G.] Donnan has represented the company on company & battalion drill not over five days—the time I was at home & with you in Dubuque. I have never been reported sick, have never been absent from company or battalion drill or dress parade except when at home or with you except once—[that was] dress parade on Sunday when the hour was changed without my knowledge.

Out of 13 non-commissioned officers, we have but two to act. I might say some things more pointed but will not for fear it may come back. Our sutler, Mr. Candy of Independence, has just come and I shall probably have to pay him $15 for a pair of boots. Alf[red] and A[lbert] Cordell, Henry Turner, Jacob Glass, E. F. Porter, A[lonzo] L. Shurtleff, A[dam] Hoover, Henry French, B[enton] F. Colburn, & one of the Chase boys are on the sick list of those from Quasqueton.

My health is good except a bad cold. I am satisfied I cannot endure much exposure. Tell me the news when you write. Give my respects to Alice and the girls. Kiss the children as usual. Yours as ever, — O. Whitney

Letter 9

Camp Reed, Jackson, Tennessee

March 6th 1863

My dear wife,

Our regiment is now obliged to do picket duty every other day & expecting to be gone on such duty tomorrow, I conclude to write you a few lines now for fear I may not do it under several days if I neglect doing it now.

The 50th Indiana left this morning, their destination said to be Lexington, some 35 to 40 miles east and north of Jackson. Their tents were left behind & I should think they had not more than one blanket apiece & many no overcoats. It was raining when they marched out of their camp. I expect we shall be called upon to leave in the same way one of these days. In such exposure there is necessarily much suffering & those who are delicate run the risk of losing life. One great difficulty the soldiers experience on such expeditions it that of getting wholesome food. For want of that, many become sick. A regiment, as today, may be accompanied with but four teams which with almost impassable roads allows of but scanty supplies for only a few days. Each company may have not to exceed two camp kettles & two spiders. With these must get all they have to eat & you may be assured it frequently makes lively work & many got to bed hungry after a long march. In the morning, if the march is renewed at an early hour, many commence the day’s march hungry. There are always some of the men ready to find fault with any kind of usage they may receive. Such curse and swear at their officers & blame them as the sole cause of all their trouble, while there are others who do not grumble at any kind of usage in the unavoidable line of duty.

You have written several times about sending some things to me. From what I have seen, I am content to let you & my kind friends keep their good things to eat or wear them at their leisure. The two boxes Mr. Candy (our sutler) brought with him from Buchanan county cost $24 just to get across the Mississippi & then after the things (food mostly) reached here they were eaten in such quantities as to make many of the boys sick. Some parents were so foolish as to send liquor to their sons. It is needless to say the liquor was drunk with the usual effects & results. The inducements to drink in the army are so great that friends and relatives need not be to the trouble of sending intoxicating liquors. After the Mississippi is fairly open to navigation, the expense of transportation will not be probably one half what it is now.

For myself, I want no boxes sent or consigned to me until I get a supply of money. You will find one one of my letters directions about strawberries and raspberries.

Our, or this brigade, is broken up for the present, but the direction of letters will be the same as heretofore. Give my respects to all friends. Remembering the children as usual. Affectionately, — O Whitney

Letter 10

Camp Reed

Jackson, Tennessee

March 19th 1863

My Dear Wife,

Yesterday morning I went out on picket guard & did not return till noon today & found a letter from you. Some things in yours are more interesting than agreeable. For instance, the report nuisance circulates of you & Mrs. H. It is needless to take any notice of his slanders. No one that knows him believes anything he says unless they first know it to be true. I could name certainly one more of the same stripe.

I cannot learn anything definite about pay. It will probably come some time unless the government breaks down in which case greenbacks will be of no account. Although we are doing nothing in a military view, I am for one kept busy almost all the time. So many sick to visit & then the dead or their effects to attend to. Two more of my company have died within a week—Joseph Moore and B[artimeus] McGonigil. The latter died yesterday. A[lonzo] L. Shurtleff is thought to be getting better. Warren Chase is at the post hospital. The left top of his lungs is said by the doctors to be entirely consolidated. [The] Cordell boys [Albert & Alfred] about as usual. Witten doing duty. Henry French has a large swelling on his neck. I can only send you a short letter now but will try and write often. We know nothing of going to Vicksburg.

I have just received the papers & bundle of linens. Respects to friends, &c. Kisses for the children. Love for you. — O. Whitney

Letter 11

Medon, Tennessee

May 6th 1863

My dear wife,

You see I am in a new place (Medon). It is 13 miles from Jackson, southeast on the Ohio & Mobile Railroad. It is the rout taken by the cars to and from Memphis. The cars at Corinth are 93 miles from Memphis by the Charleston & Memphis Railroad but there is a link out from Corinth to what is called Grand Junction which is not in repair so the cars have to run to Jackson some 64 miles and then they are still 92 miles from Memphis. The roads run somewhat like the following diagram. Corinth is lower down than I have represented.

Yesterday we moved everything from Camp Reed to a new campground much nearer Jackson & a very pleasant place. We had pitched our tents and were beginning to provide for something besides the bare ground to sleep on & were getting along finely when word came that we were to move in the morning. The morning came, this morning, & by 8:30 a.m.we—the whole regiment—were at the depot of the Ohio & Mobile Railroad. Co. H & B were under the charge of Major [George W.] Howard [and] ordered to Medon. Other companies went farther down towards the Junction. We moved off about 10 a.m. & reached Medon about 11:30 a.m. where I am at present with most of, or, a part of the men. After landing here, a very heavy detail was made for the purpose of relieving the pickets that were then out. I will give as near as I can a diagram of roads and picket stations. The men stay at the stockades three days before they are relieved. The pickets regular are relieved each day in the morning.

8 o’clock p.m., May 7, 1863

Last night I was too tired to finish this letter & contrary to my usual practice, I did not burn it up but left it to finish tonight. And if I do not finish it this evening, I may leave it for some other time. Notwithstanding we are moving here & there & do not know from day to day when we shall be the next, the soldier’s life has a sort of varied monotony about it that makes a diary less interesting than you at home would suppose.

Yesterday we landed in the little dilapidated town of Medon, sent out pickets, & relived 11 stations. Then I mounted a horse and rode 8 hours to visit the picket stations after which, attempting to write you a letter, failed from fatigue, made up my bed on the floor and went to sleep dreaming of home & everything else that one ever thought of—and more too. And that makes up about the sum total of the day’s labors & though other days may be different, the difference is in quantity & not in kind.

This place seems to be built for the sake of having a place to look at or name, I could not say which. It must have contained not to exceed one hundred and fifty people in prosperous times, and there must have been 8 or 10 stores. Most every house holds a widow and a few darkies attached in the little darkey houses. I have called on two of these widows in this place, one just before dark of whom I purchased two pair of cotton socks for $1. She is a great raw-boned double-jawed woman, has two married & three unmarried daughters living with her, & the usual complement of negroes. I did not fall in love with her or her daughters nor the wenches. The other widow is something more of a personage. She is accounted to be rich but she says she is nearly ruined by the soldiers. I was Officer of the Day yesterday & as such she sent to have me come & see her. A new set of soldiers coming in, she felt a great anxiety to see what kind of Yanks were to guard the town & if possible conciliate them so that safe might be safe from pecuniary loss. I did the best I could to assure the lady that she need not fear harm from our detachment of the 27th Iowa if she would preserve a strict neutrality which of course she promised to do. Today I called on her & found her in good spirits, safe & sound to all appearances. She keeps a piano but does not play it. Has a little daughter called Peter something (I don’t recollect what now). The last name is Swink. The daughter is some 11 years old, goes to school, does not play the piano. The widow has a few wenches. The balance are in Texas. The widow is smart but too old to captivate. Southern women vary very much in what constitutes female charms, &c. Some are somewhat attractive, and some are somewhat otherwise. Most of the ladies in this part of Dixie either chew tobacco or dip snuff. You probably know what chewing means, Dipping snuff is in this fashion. They take a stick of Dogwood & split one end up fine, then dip into snuff, then chew & suck it. Sweet pretty-looking young ladies will spout tobacco spit like a barroom loafer.

I have not smoked since the 22nd of February. I will not try to write more now. It ia very hard work for me to think of anything. Kisses for the children. Yours with love as ever. — O. Whitney

Letter 12

Camp Opposite Little Rock, Arkansas

October 4th 1863

My Dear Wife,

Yesterday I was gratified at the reception of three of your letters dated August 30th, September 6th, and September 13th. It had been nearly or quite a month since receiving any intelligence from you. I was anxious to learn whether you have received the money I sent by the chaplain although I had previously been informed that the money was left at Independence [Iowa].

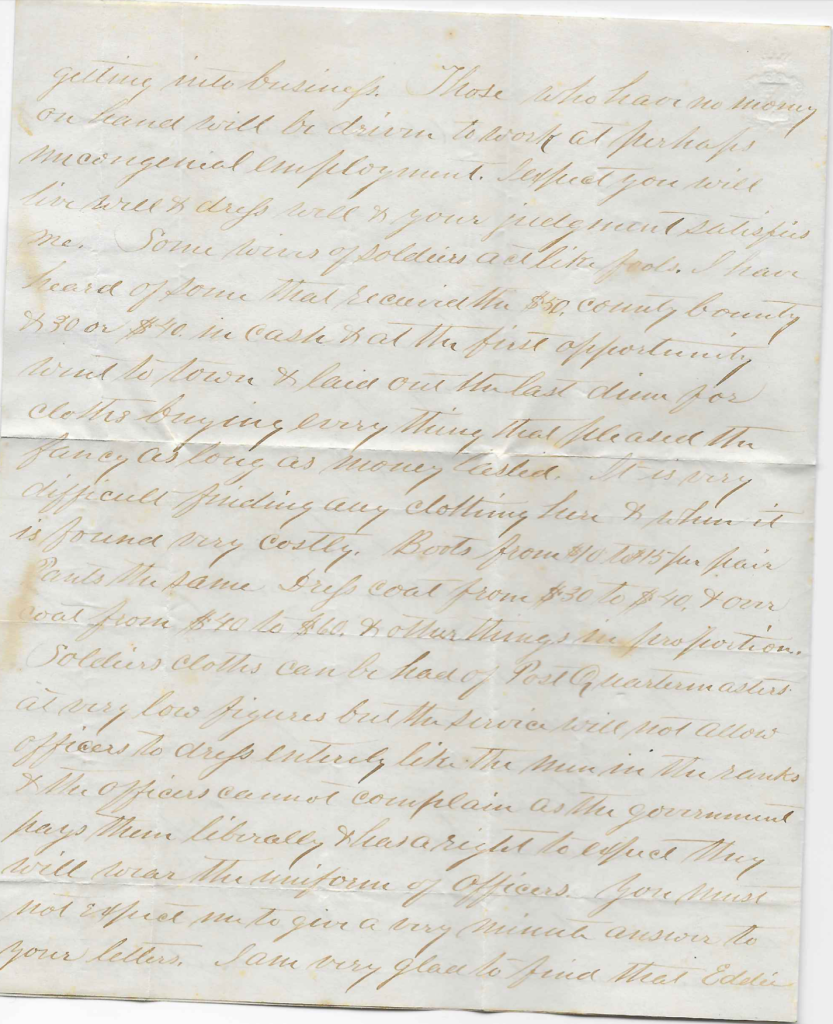

I hope you will keep the money as safely as possible for I send you all but what I spend for my own personal expenses. I wish you would let me know when you answer this how much you have on hand. I would like to know that I may make some calculation as to the amount I can save. When I leave the service, I shall be out of any income and also out of business & as there will be thousands in the same situation, it may be difficult getting into business. Those who have no money on hand will be driven to work at perhaps uncongenial employment. I expect you will live well & dress well & your judgment satisfies me. Some wives of soldiers act like fools. I have heard of some that received the $50 county bounty & 30 or $40 in cash & at the first opportunity, went to town & laid out the last dime for clothes, buying everything that pleased the fancy as long as money lasted.

It is very difficult finding any clothing here and when it is found, very costly. Boots from $10 to 15 per pair. Pants the same. Dress coat from $30 to $40. And overcoat from $40 to $60, and other things in proportion. Soldiers clothes can be had of Post Quartermaster at very low figures but the service will not allow officers to dress entirely like the men in the ranks & the officers cannot complain as the government pays them liberally & has a right to expect they will wear the uniform of officers. You must not expect me to give an very minute answer to your letter. I am very glad to find that Eddie recognized me & now that I think of it, I will enclose the other likeness in this letter. It is so small I think Eddie will be puzzled to make out the original.

I hope you will not allow yourself to become nervous on account of my absence. The soldiers wives are much worse situated than you are for when furloughs are being granted, only five in a hundred can go home at once and generally by the time one set gets back, the order granting furloughs is revoked or the regiment is under marching orders & then it costs a soldier several months pay to go home & return. It costs an officer more than a private as it is customary to charge them higher fare on the river and full fare on the railroad. If the order should be renewed allowing leaves of absence, I shall make an immediate application but I do not expect any opportunity for some time. It will depend entirely upon what is intended to be done with us. If we should be posted here, we shall be allowed furloughs & leaves of absence. You must make no calculation on seeing me until I let you know. Now that you have a house full of friends, I dare say you wil not be lonesome.

I have no news of interest. We go to bed at night without any fear of enemies or of being disturbed. There are more Union people here than we have found at any other place. The Arkansas River is very low—so low that the boys wade it in places. The evenings are very cold, not freezing, but if anything worse. One feels the cold here more than in the North. The atmosphere is different here from Iowa, rendering a slight degree of cold very penetrating & uncomfortable. I wish you could make me a couple of good shirts—fine woolen of some delicate tasty color. If you should make them, have them made very large, a fold & buttons in front with a band round the neck. You could send them by mail. Others have them sent by mail. You need not send me paper as I can get it readily. Postage stamps cannot be had for money. I will close this prosy letter but not with the promise of doing any better next time. With love as ever, — Otis Whitney

Letter 13

Camp near Little Rock, Arkansas

October 20, 1863

My Dear Wife,

As it has been a number of days since I have written to you, I conclude to write you a few lines now although I have nothing to communicate but the old story—as well as usual & doing nothing of any account. A soldier’s life is one the most calculated to make anyone reckless & lazy. I have stopped writing long enough to eat breakfast & now that we are about prepared to to put up a log cabin. I must be very brief for we must move the tent to another place to make way for the cabin. I shall not have an opportunity to work today as I have quarterly report of ordnance and ordnance stores to make out.

In some respects we are living very well & comfortably. For breakfast we had nice white fish, corn meal, quick cakes with melted sugar and coffee. I get our supplies from the Division Commissary & do not have to pay as high as you do at home. Sometimes we get potatoes but generally go without for the best of reasons. We have been well supplied with sweet potatoes lately at $1.50 per bushel. Chickens are to be had occasionally at 50 cents apiece. We now have very nice persimmons. I wish the children could have some. They cannot be transported because when fit to eat, they are as soft as a thoroughly rotten apple. They are very harmless & the saying is that no one can eat too many.

The 50th Indiana have been removed fifty miles up the river. We have received no mail a long time. The occasion of the long delay is that the White River is getting unprecedentedly low and the fleet sticks on the sand bars for days at a time.

I have just stopped long enough to move the tent & everything is covered with dust half an inch deep or less. The wind has been blowing for two or three days is the reason of so much dust. There are yet no signs of leaves of absence & I begin to thing the expense from this point too much. I should not think so if it were not that I may be holden by the government for $200 or $300 worth of company property that has been lost, destroyed, & thrown away. I could not afford both now. The government hold captains [responsible] for every article put into mens hands.

I cannot write more now. I hope to hear from you soon. Love to all & yourself, — O. Whitney

Letter 14

[Note: The following letter is from the collection of Greg Herr and was transcribed and published on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Camp near Little Rock, Arkansas

November 1st 1863

My Dear Wife,

I have before me your letters of the 5th, 8th & 12th of October & I suppose it will not be out of order to answer them all at once—especially as i have sent you one letter since receiving these. It was sealed up and stamp on envelope or I should have opened & at least acknowledged the receipt of these last letters. Your stamps & photographs came safe & are very welcome—the first because it saves me considerable inconvenience & the latter because it places your image before me in the best possible form. I think it is a fine likeness and those of your acquaintances to whom I have shown it pronounce it perfect. It seems to me you are thin—more so than usual. You do not take after your Father i that respect, but rather imitate your worthy stepmother, who I believe was not remarkably adipose. I believe, however, she was a slippery creature if not very greasy. But I will turn the leaf & change the subject.

It is now nearly 3 p.m. & I have just completed a muster & payroll having worked continually on it today. I have not a complete set of muster & pay rolls made out for the months of September & October & am ready for the pay master to come along as soon as he pleases which he may do in two weeks, a month, 2 months, or longer. Every two months we are and all the forces are mustered & the periods are stated to wit: the 31st of October, 31st December, 28th or 29th of February, 30th of April, & so on through the year. Those that are not mustered lose their pay for that term unless they get an order which restores them to pay.

Mustering is this—after we are in the U. S. Service, the muster roll is made out with all the names of those belonging to the company, their date of enlistment, where enlisted, by who enlisted, when mustered into the U. S. Service, for what period, where mustered, by whom mustered, by whom last paid, to what time paid. Then the company is paraded & the names of all answering present are put down in a column as present & all those absent. Their absence must be explained in a column of remarks. That is what is called mustering for pay. Muster and pay rolls are just alike with the exception that the payroll extends to the right 6 or 8 inches further with columns for amount of pay, time to be paid for stoppages, &c. &c. &c. a column for each man to sign his name as a receipt to his pay, and then a column for a commissioned officer to witness the receipt of each man. I will not take up more room with this.

Last night I had the pleasure of spending the evening in the company of Mr. & Mrs. Hastings at the St. Anthony Hotel in Little Rock. They reached the place Thursday night & got tipped over before crossing the river. Tipped over in the sand in an ambulance from the depot to the hotel. They came as all have to come, by the river to DuVall’s Bluff, thence to this place on platform railroad cars. They had proceeded down the river as far as the famous place Vicksburg—the doctor being on his way to join the Engineer Corps—when McPherson’s adjutant ordered him to report at Helena, Arkansas, and from there proceed to his regiment, the 27th Iowa, at Little Rock. Yesterday the doctor was very busy trying to find a place to live. I think Mrs. Hastings will not find it very agreeable here.

I have been writing so much that I will stop with this page. My health is very good as usual. One of our captains started home this morning for Iowa to get recruits. He will probably have an opportunity to stay some months and get better acquainted with a wife he married a month or two since when home for a few days on leave of absence.

If you send me shirts, you can send by express as there is an agency here. With respects to all and love to yourself & the children, goodbye for the present. — O. Whitney

Letter 15

Memphis, Tennessee

January 1, 1864

My dear wife,

I wish you a Happy New Year—also Emma and Eddy. I am trying to have a comfortable New Year’s day if not a happy one. I am writing with my paper on a book called Order Book & am sitting close up & almost over the little sheet iron stove. Yesterday towards night the weather became very cold (for this latitude), blowing the snow like a regular Iowa storm. It is to me the severest storm I have experienced in the South. This morning it is very cold—the ground frozen hard. My ink froze up in the night. We should perish if out in the open field as we were last year unless in the woods where the trees break the wind and where we could build up large fires. Day before yesterday I was field officer of the day. The morning was fine and I thought I should have a pleasant day but I was disappointed.

Just after dark it commenced raining and rained more or less all night. A little after 12 p.m., I started out & went twice along the picket line & returned a little before 5 p.m. The distance around the picket line is about 5 miles. It is not a very agreeable job in the night. I have blankets that I can keep warm nights & when the wind does not blow & it is not so excessively cold, I can keep warm enough.

We are having disagreeable times with the field officers of the regiment. Charges & specifications have been drawn up & served upon Col. [James I.] Gilbert, also upon Lieut. [William G.] Donnan. I think Dr. H. is at the bottom. The worst of it is they have my name down as a witness against the Colonel & the first witness against Lieut. Donnan. I do not know what they expect to prove by me. Lieut. Donnan thinks I am interested in the prosecution against him when I cannot think what they want me to testify to & knew nothing of the charges until they were drawn up & did not know I was a witness until after the charges were handed in. The result of the thing is I shall have no friends on either side. I wish we had at the head of the regiment some men who understood military a little better. I have not yet called to see Mrs. D. and now I shall not. We have hitherto had very good feeling among the line officers of the regiment, but I am afraid it will not continue long.

I expect you will exercise your own judgement in the conduct of your affairs. If you choose to give Henry’s family the cold shoulder, I have no objections, or if you wish to become somewhat isolated from society. When I wrote about your coming down here I had intended or expected if you come you would stay 3 or 4 months or perhaps so long as the regiment remained here, or at any rate until spring. You probably noticed on the envelope of the letter of the 28th that my application for a leave of absence was not granted. I did not much expect it would be, My chances for getting one are less now than at any previous time because Lieut. Wilcox is Acting Regimental Quartermaster & Lieut. Donnan is Acting Adjutant of the Regiment so that if I should go away, there would be no commissioned officer with the company. Lieut. Donnan has never been with the company but a few days at a time since we left Dubuque & I do not expect that Lieut. Wilcox will ever be with the company again to do duty.

Mr. John Smyser, Orderly’s father, made us a first rate visit. He brought a lot of sausages, butter, honey, & so on. We have plenty of butter and honey yet. With love to you and kisses for the children. As ever, — O. Whitney

Letter 16

[Note: Whitney refers to Fort De Russy throughout this letter as Ft. La Rogue for some reason.]

At Alexandria, Louisiana

On board Steamer Diadem [a sternwheel packet]

March 19th 1864

My dear wife,

We have been at this place three days and how much longer we shall stay, I doubt if anyone knows. The next day after the taking of Ft. La Rogue [Fort De Russy] , we went aboard the fleet & moved up to this place meeting no opposition. Gen. [A. J.] Smith with some gunboats & 5 transports remained at Ft. La Rogue to finish up the job by removing the cannon and blowing up the works. They came up last night having accomplished the object. In the bursting of one of the cannon which they purposely burst, several men were killed & wounded. One Lieutenant had his head completely blown away. One man had both legs cut off. Another both arms. All the result of carelessness.

The same day after reaching this place, the men were disembarked & all but the sick have been shore since. Many are getting the ague & fever & it seems to be very unhealthy. When we marched upon Ft. La Rogue we left behind some said to be sick with the small pox. Most if not all of the soldiers have been vaccinated so that I think they will not be likely to have more than the varioloid. I have been vaccinated twice since being in the army. Almost all of the river towns have more or less cases of small pox in them.

It is the expectation that we shall be joined here by Gen. Banks who has a large force of mounted infantry & that after a little, we shall advance up to Shreveport, distant by land 184 miles & nearly 300 by water. I hope we shall not attempt to go if we have to walk for I do not feel like walking 368 miles now & in this climate.

We have some 22 gunboats along and I suppose the good people at home think the infantry will not have much to do with such help—especially where some of those gunboats carry as high as 30 cannon, but a little observation would correct some mistaken notions with regard to the supposed invincibility of gunboat fleets. The little Fort La Rogue defied our whole fleet of gunboats & persons said they would have driven back our fleet or sunk it. Certain it is that the gunboats fired but our shell to my knowledge, & that bursty directly over the heads of Co. H, 27th Iowa Infantry.

Living is rather expensive on the boat for the line officers $1.50 per day. I am in hopes the expedition will do up its business as soon as possible & return. I believe we were ordered to report at Memphis or Columbus. This country is full of sugar. 100’s of hogsheads of sugar have been found. The gunboats are very busy taking on cotton, When sold, they get a part of the proceeds as prize money. With love as usual. Yours affectionately, — O. Whitney

Letter 17

Camp back of Memphis, Tennessee

June 17th 1864

My dear wife,

I received yours of the 5th and 8th on the 13th and 14th—one on my birthday and the other the day after. You must know pretty near how old I am for when we were married, I was several years the older or elder. At any rate, I am so old it hurts my feelings to talk about it. Where the years have gone to & how they went is a mystery to me.

My sister Martha 2 years younger than I am is now a little old maid & I can think of her as only a girl just home from school. Well, it can’t be helped. Neither can I help thinking of myself as an old fool. But I hope if I am permitted to live for years to come, I can do something more for my family that I have yet done or shown any ability to do. Those children are not at all provided for and in less time than we have been in Iowa, Emma become a married woman when I presume she will expect a setting out, & in a few years Eddie will want a farm or some other substantial evidence of his Father & Mother’s economy and thrift. My wish is to be able to do something for them. But to do it, things must prosper more in future than in the past. One of the great desires in my life is to live to see the children grow up.

You write to me about resigning. Now that is a thing that cannot be done very easily. If I should undertake it & be successful, I could not probably get around under 3 or 4 months & perhaps much longer. I have been tempted often to undertake it. One consideration that has kept me back is that I might be drafted. When I hear from Mr. Shurtleff’s folks in Oregon & how successful they are, I wish myself there away from the commotion & uncertainty of war. They, from accounts, appear to be doing well and like the country much.

The condition of things & the prospect in this country is very dark to me & I begin to feel as if I would prefer to have rest. Notwithstanding the noble & continual efforts of many at home & in the army, I begin to feel as if we do not deserve success in this struggle. The northern towns & cities swarm with those who do not wish our cause success and the army is almost controlled by those who wish the war prolonged indefinitely. Favoritism & partiality are carried to that extent as to become disgusting & disheartening. True patriotism is scarce & many of our most prominent men are ready to barter the best interests of the country for some prominent office or for money. I am not sure but the taunts of the South that the mercenary spirit of the North would prove its ruin. While the South is sacrificing everything for its cause, the North is reveling in wealth the profits of the war. Those who contribute most are least able to contribute. I wish you would keep an eye on this & not be too liberal for when the war closes, or even before, I expect there will be a reaction that will grind the face of the poor into the very dust.

The swimming times that now prevail in the North will not last always and not even as long as the war has already continued. It looks to me as if the wheels are getting clogged. These 100 days men called out is the beginning of temporary expedients—the drowning man catching at straws. If Grant is successful in taking Richmond, all will go well. If he is not, then the botch work will appear.

My health is improving. We are under orders to be ready to march at an hour’s notice—after [Gen.] Forrest I suppose. I received Martha’s letter and will write to her soon. The annual interest of $10 has not yet been paid Father. We expect pay soon. There is no use in applying for leave of absence. Remember me to the children. Yours affectionately, — O. Whitney

Letter 18

Holly Springs, Mississippi

August 11, 1864

Dear Father,

As I have an opportunity, I am trying to improve it by writing some short letters to my friends. I with my company, regiment, & brigade (2nd Brigade, 3rd Division) have been camped at this place since the 4th waiting for the railroad bridge to be built across the Tallahatchie River, To build that bridge the rebels had to be driven back from the opposite bank where they were entrenched—that was done yesterday by Gen. [Joseph A.] Mower who commands the 1st Division, 16th Army Corps. He is a fighting general & is undoubtedly working for the 2nd Star as he only wears one now. Waterford is 10 miles farther south on the railroad & the bridge crossing the Tallahatchie River is some 7 or 8 miles further on.

This expedition consisting of 15 or 20, or 25,000 men is under command of Major General [Andrew J.] Smith. I think on the whole everything considered, he is a safe commander of such number of forces as we have here. He is a fighting man & seems to delight in the thunder of artillery. I have seen him sit on his horse where the shot and shell and Enfield rifle bullets were howling and whistling all about, as cool & unconcerned as most persons could be sitting down to eat in his own house. Gen. Mower the same. And Col. [David] Moore who commanded our [3rd] division in the late expedition & Battle at Tupelo is a perfect savage. He will order his men to charge without any preliminaries upon a battery regardless of men or guns. For example, he ordered us to charge upon the battery at Lake Village on our return up the Mississippi River from the Red River expedition & after we had got up to within close canister range, we came to a bayou that we could not cross. Their lines of infantry was also in ambush on the opposite bank from 10 to 15 rods off. As might be expected, our men were slaughtered. But we outnumbered them so that we should soon have cut off their retreat & they fled after they found our men would not fall back.

As yet my clothes even have not been touched but I have had many very close calls—too many to specify in a letter. At the Battle of Tupelo, however, I had one so strange that I must tell it that you may see by what singular circumstances one’s life is saved. Our brigade was supporting the front line within about 15 rods & was by order lying down. The bullets, shot and shell struck the ground just behind us mostly so that if we had not lain down, hardly a man could have escaped untouched. Most of the time while laying there, I had rested upon my elbow so as to look around & see what was going on, but getting tired, I dropped my head down flat on the ground which I had hardly done before a 6 lb. solid shot passed over me lengthwise within three inches of my back and heels, bounded out & stopped within two rods. The only man who was fidgety & got up in the heaviest of the fight had his right forefinger shot off. In some places our brigade suffered more severely than the front line.

The next day we charged on a battery and might have been easily used up if the enemy had not run when they heard the order for us to fix bayonets. We had to charge so far that not more than one quarter of the line of the 27th Iowa Regiment was able to come up to where the enemy had their line. The rest were exhausted or struggling along as their strength would permit. It was very hot & many fell down blind & sun struck. But I will not continue this letter further in this strain.

The country is full of Rebs & they seem to love to fight. The country is full of corn with some cotton. When we subjugate this country by force of arms, I shall expect to be an old man. If the backbone of slavery is broken, there is no excuse for continuing the war to free the slave. If the freeing of the slave is not the object, but independence on the part of the South, who has counted the cost of subjugation? And can it be done? But I will stop.

My health is good. I hope to hear from you & that you & mother & all are well. I have heard nothing of Olive in a long time. With love to Ma and all the rest, I remain with the greatest respect your affectionate son, — Otis Whitney

Letter 19

Camp at Nashville, Tennessee

December 6th 1864

My dear wife,

I have seated myself on my roll of blankets & commenced a letter to you not knowing whether I shall have an opportunity to finish before having to fall into line to repel Gen. Hood’s army. We are entrenched behind strong temporary works which we have thrown up since the 3rd inst. We are on a high and commanding hill with a section of a battery planted on it. Cannonading has been going on almost all the time since we took our position with the exception of part of the night & it has just now commenced again 8:30 a.m.

We have no fears of an attack in the daytime, nor much in the night. But a night attack would to a great extent deprive us of the use of our artillery. It is no doubt the intention & policy of the rebels to attack us in the night & then by force of numbers to overwhelm us—precipitating themselves upon us in massed columns with insane and reckless fury, hoping to break our lines. We have a force large enough to whip the rebels in the field, I think, but it is not the intention of our commander to move outside our works to fight. Gen. Hood cannot afford to remain long before the city & if he attempts to retreat, that retreat must soon be converted into a flight. The rebels do not reply to our artillery & have not except once the first afternoon when they planted a section of a battery (2 guns) and attempted to shell us but soon gave up the attempt as useless as they could not reach us with their shell. Judging from appearances, they are short of artillery ammunition. We have a line of entrenchments 7 miles long that is the outside line. Inside are rifle pits and two formidable & very commanding forts full of heavy siege guns.

Yesterday Gen. Hood under a flag-of-truce sent in a demand for an unconditional surrender of the place with all the men, arms, munitions, &c. as a means of saving the needless effusion of blood. I do not know what reply was returned to the demand, but we are still here & still unattacked except that lively skirmishing is going on all the time night and day. Tonight my company go on picket—or rather into the skirmish line. We were on the first night after taking this position but there was no skirmishing that night. The skirmishing has been almost entirely on our left. On our left to the river above Nashville where our lines touch the river, it is upwards of three miles.

Nashville is a rough, to me, not very pleasant place. There are quite a number of fine houses in town & some very fine residences just outside of town. The Capitol is built on a hill overlooking the city and is a fine structure, said to have been at one time the finest Capitol in the U. S.

Lt. Smyser has been sick since reaching this place—that is, he has not attended to any company duty in the field. I do not think he will be sick long. At any rate, I hope not, as I expect we shall soon have a long march to make either after Hood, or away from him. Our men are all in good spirits & I believe would rather have an attack from Hood than not. The weather has been quite comfortable since our arrival here with a slight rain at two different times. Today I expect to get a dog tent & then I shall be as comfortable as a dog can well be in a strange place away from home. The other day I saw Lt. Johnson who brought the doll for Eva Scott. He said it cost only $5. I would have bought one for Emma if I had had a chance. I am Officer-of-the-Day & must be looking around. Accept love and kisses for the children and yourself, — O. Whitney

Letter 20

Camp 12 miles from Columbia, Tennessee

December 20th 1864

My dear wife,

I avail myself of a few minutes leisure, or rather respite from marching, to send you a few lines. You have probably heard long before this all the particulars of the two days fight before Nashville & how the Federal forces defeated Hood’s forces. The battles were on the 15th and 16th. On the 17th our forces commenced the pursuit—that is, the infantry. The cavalry were in pursuit the night after the fight. The roads were very bad & it rained most of the day. The 18th continued the chase & camped long after dark on the battlefield of Franklin with the evidences of the sanguinary contest all around us—cast away knapsacks, haversacks, blankets, cartridge boxes, and various kinds of small arms. Dead horses lay scattered around and new made graves were in the midst of our camp & long rows in sight near our fortifications.

The 19th yesterday we were up prepared for the march at 8 a.m. Left encampment at 8:30 a.m. but did not make a half mile before noon—raining all the time and weather cold. We had a very disagreeable march of 12 miles to this encampment. We are now resting in camp for one or two reasons. Our division supply team is not yet up although wagons were coming up all night. Besides, we are within 10 or 12 miles of Duck River over which it is reported our forces cannot cross—the late heavy rains having swelled the river too much to be forded. Hood’s forces are across & he is probably making every effort to reach and cross the Tennessee River. Our march thus far has been on what is called the Franklin Pike. The Pike or road is nothing more or less than a graded macadamized road. It would be entirely out of the question to march on a common earth road. On such, I do not think our army could make two miles a day. The Pike is getting out of repair which delays our march very much, at times obliging us to stand hours waiting for teams to get past a broken place in the road. I rained part of night before last and all day yesterday.

We may be ordered to move any minute so that I must hurry up. I passed through the battles unharmed but was dreadfully fatigued. In the charge on the 16th, I had a full haversack & canteen, a rubber blanket, and my overcoat which was wet and very heavy. Although not carrying near so much load as many others, I gave out with fatigue for a time and fell behind apiece but regained the front before the line permanently halted. I am feeling very well—better than one could expect after being exposed to so much inclement weather & especially sleeping under & on wet blankets.

I received yours of December 12th with a few lines from Uncle Nathan. I had written him a letter. Randolph I have observed does not feel very much inclined to carry on correspondence except on business.

There is a sound of heavy skirmishing on the left & it may be possible the cavalry are trying to pen up some of the rebs. I do not know when I can send this. Love and kisses for you and the children, — O. Whitney

December 23, 1864 I have not had an opportunity to send this till today and now I only put it into the hands of our postmaster. We are camped on the banks of Duck River near Columbia. The weather has been very stormy but now it is fair but very cold. I am well. Yours with love, — O. Whitney

Letter 21

[Note: The following letter is from the collection of Greg Herr and was transcribed and published on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Camp 27th Iowa Infantry

6 miles below New Orleans, La.

February 22d 1865

My Dear Wife,

Here we are at last in the mud & rain waiting for further orders & on the identical ground where the British army was defeated by Andrew Jackson some 49 years ago. We reached New Orleans yesterday afternoon, lay on the opposite side of the river an hour os so, and then moved down to this encampment. Yesterday we were amused & interested in watching the scenery on either bank of the river as moved along down. After passing Baton Rouge, the banks present the appearance of fine residences in the suburbs of a great city. All the time there were from one to a dozen sugarhouses in sight. There were many beautiful mansions and nearby the negro quarters gave the appearance of fine little villages. On some of the plantations there must have been fifty or sixty negro houses generally painted white—sometimes yellow. One house the main part had 15 windows in a tier & was three stories high making forty-five windows in front and then one each side were wings, themselves fine houses. All around were heavy pillars. The grounds around were planted with large evergreens, live oak most conspicuous. Orange trees in profusion shining with golden colored oranges, but they are not fit to eat being as sour as lemons. Among the large shrubbery, the dark green foliage of the fig was prominent. Notwithstanding these beautiful sights, there is an unsatisfactory feeling pervading that I can account for in no other way than that one does not like the location of a residence nearby a vast river several feet higher than all the surrounding country.

The river is dammed up on both sides or the whole country where those large mansions are would be overflowed so that river steamers might float at pleasure. We have seen no sunshine for two or three days and last night the regiment debarked in the rain. I was brigade officer of the day & remained on the boat over night.

It is expected that we shall be on board Gulf Steamers within a few days. We shall no doubt have a touch of that nautical complaint sea sickness. Out destination is said to be Mobile. There we shall have a new experience in warfare. Dr. Hastings has gone into a hospital in the city or expected to last night when I last saw him. He may get an order to proceed North as Lt. Snyder did at Vicksburg. I suppose he—the Dr.—has written to Mrs. Hastings. If not, and this should be the first she hears of his being sick, say to her that the Dr.’s trouble is neuralgia in the head. I think he will be about in a few days and perhaps accompany us to Mobile.