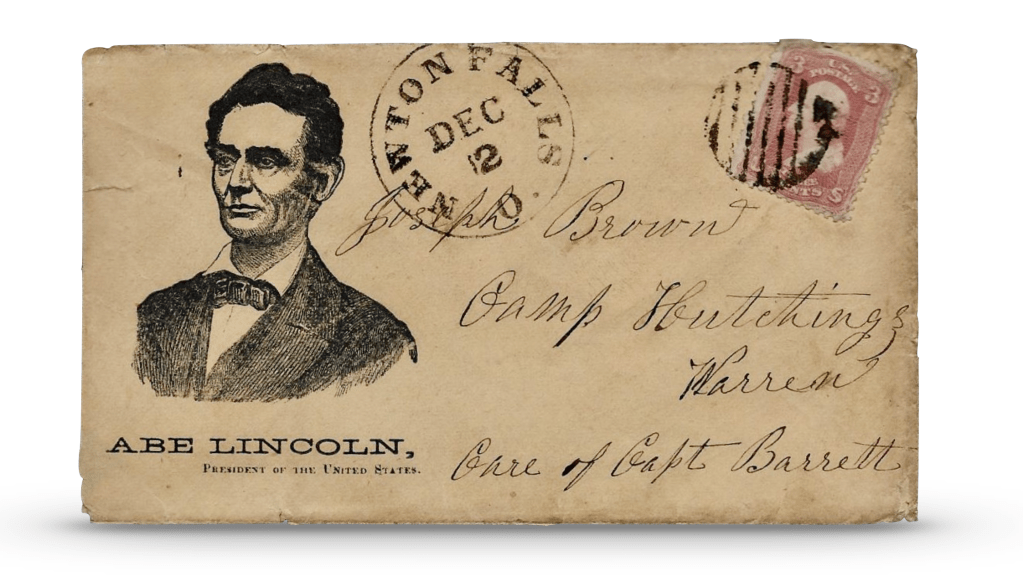

The following plaintive missive expresses the pangs of an anticipated long separation experienced by the wife of a Union soldier who has just enlisted for three years. It was written by 35 year-old Mary Gifford (Richmond) Brown (1826-1891), the daughter of Allen Richmond—who passed away on 1 November 1861—and his first wife, Betsey Dennison Jones (1799-1830). Mary and her husband were married in March 1844. Because she was under the legal age to get married in Ohio and her parents opposed the union, they eloped to Bedford, Pennsylvania where a local Justice of the Peace solemnized their marriage. Once hitched, they settled in Newton Falls, Trumbull county, Ohio, where Mary’s husband made a living as a wagon maker. By the time of the 1860 US Census, the couple had three children—Libbie (age 14), Allen (age 10), and Joseph Denison, or Denni (age 7 months).

Mary’s husband was 43 year-old Joseph Brown who enlisted as a sergeant in Co. D of the 6th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry (OVC) in October 1861. This unit was organized at Camp Hutchins in Warren, Ohio; its members drawn mostly from the Western Reserve. They remained in Warren until January 1862 when they were sent to Camp Dennison for drill instruction. In March they were assigned to Camp Chase to guard Confederate prisoners. In the spring of 1862, they operated in the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia, and in June participated in the battle of Cross Keys, and again at Cedar Mountain and second Bull Run. They joined Burnside’s advance on Fredericksburg and went into winter quarters, guarding the Rappahannock. In the spring of 1863, they fought under Hooker at Kelly’s Ford, joined Stoneman’s raid, and followed Lee’s movement into Maryland, having several severe actions. The regiment took an active part at Gettysburg and followed Lee’s retreat, capturing many men and wagons. They participated in many engagements in Meade’s advance on the Rapidan and spent the winter fighting Mosby’s guerillas.

Before the Overland campaign began in 1864, however, Joseph became ill. Apparently he was with his regiment until about the 15th of March when he was taken sick and left the company encamped at Warrenton, Virginia, for Lincoln Hospital in Washington D. C. In early May, Lincoln Hospital was ordered to relocate convalescents in order to open up bed space for the anticipated wounded arriving from the Battle of the Wilderness and Joseph was sent with others to Lovell General Hospital in Portsmouth Grove, Rhode Island. His military record indicates he died there of erysipelas on 19 May 1864 after 2 years and seven months of service and separation from his beloved Mary—just five months short of his term of enlistment.

Transcription

Postmarked Newton Falls, Trumbull county, Ohio, December 2, 1861

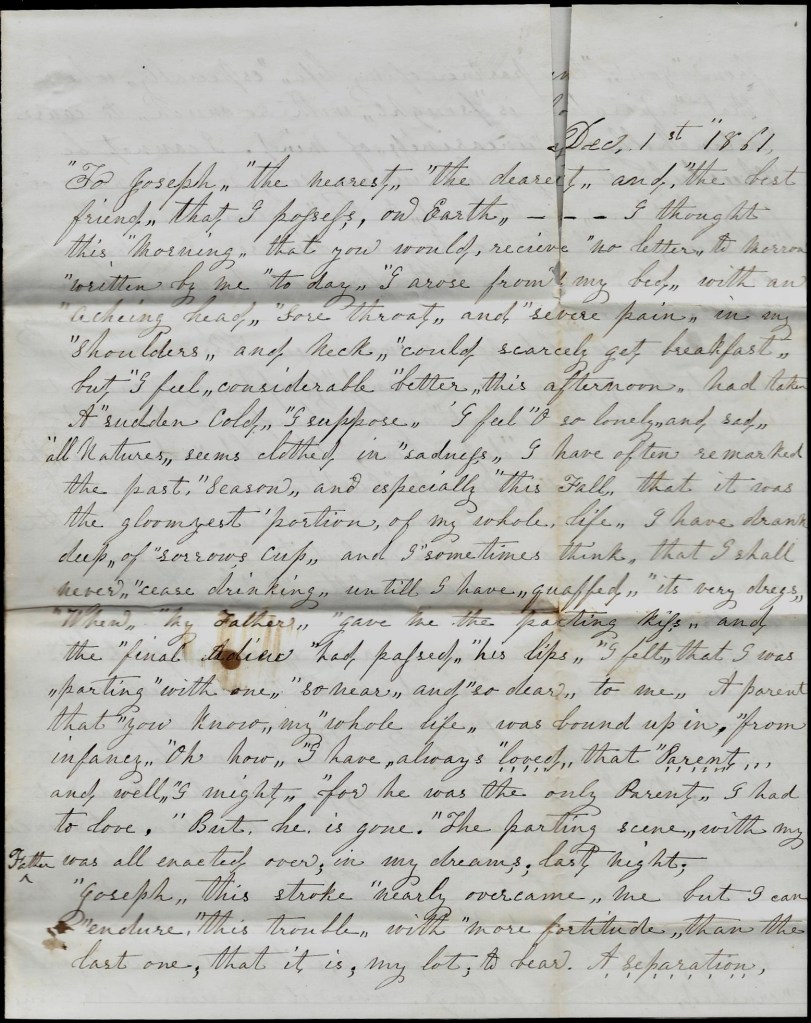

December 1st 1861

To Joseph—the nearest, the dearest, and the best friend that I possess on Earth,

I thought this morning that you would receive no letters tomorrow written by me today. I arose from my bed with an aching head, sore throat, and severe pain in my shoulders and neck, could scarcely get breakfast but I feel considerably better this afternoon. Had taken a sudden sold I suppose. I feel Oh so lonely and sad. All nature seemed clothed in sadness. I have often remarked the past season, and especially this fall, that it was the gloomiest portion of my whole life. I have drank deep of sorrow’s cup and I sometimes think that I shall never cease drinking until I have quaffed its very dregs.

When my father gave me the parting kiss and the final adieu had passed his lips, I felt that I was parting with one so near and so dear to me—a parent that you know my whole life was bound up in from infancy. Oh how I have always loved that parent I had to love. But he is gone. The parting scene with my father was all enacted over in my dreams last night.

Joseph, this stroke nearly overcame me but I can endure this trouble with more fortitude than the last one that it is my lot to bear. A separation from you—the partner of my life, especially where that separation is fraught with so much to cause melancholy and uneasiness of mind. I cannot be cheerful or enjoy life in any way when I know or feel that you are exposed to the inclemencies of the weather, to all the contagious diseases incident to camp life, and also to the fare which many of our soldiers are compelled to bear. You may fare tolerably well now whilst you remain in Warren, but you cannot always stay there. And Joseph, you cannot imagine with what awful dread I anticipate the time of your departure.

The old adage is that every back is fitted for its burthen, but I fear that mine will prove treacherous. I could endure it better if there was no compulsion. But to think that you are compelled to stay and endure the fatigue, the hardships, and the privations which I know you will have to endure, and if sick, left to the mercy or and care of others, no friend near to administer to your wants or to assuage in any way your mental or physical suffering. Oh Joseph, I cannot bear to think. It almost sets me crazy, and still I cannot stop thinking were it not for our children, it would be better for me were I in my grave than to life and suffer so much torture of mind.

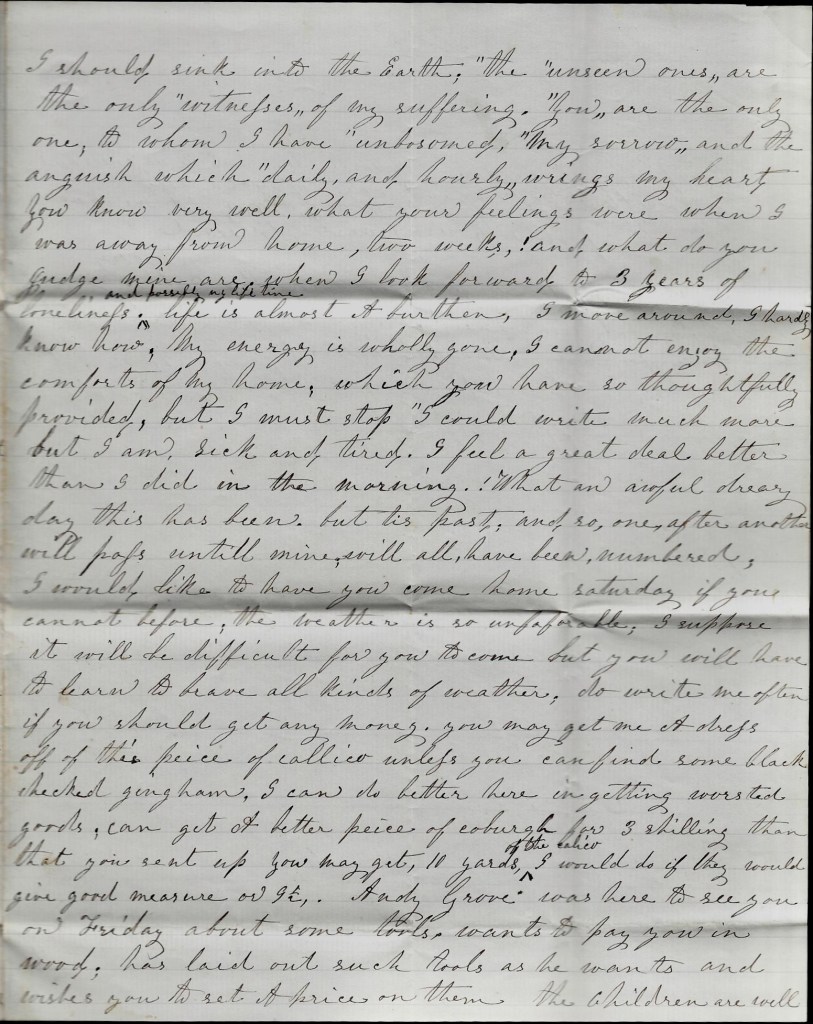

My nervous system has become so deranged that it is hard for me to govern myself. But I have managed to so far—have smothered and crushed down my feelings when it seemed as though I should sink into the Earth. The unseen ones are the only witnesses of my suffering. You are the only one to whom I have unbosomed my sorrow and the anguish which daily and hourly wrings my heart. You know very well what your feelings were when I was away from home two weeks! and what do you judge mine were when I look forward to 3 years of loneliness and possibly my lifetime.

Life is almost a burthen. I move around I hardly know how. My energy is wholly gone. I cannot enjoy the comforts of my home which you have so thoughtfully provided. But I must stop. I could write much more but I am sick and tired. I feel a great deal better than I did in the morning. What an awful dreary day this has been. But tis past, and so one after another will pass until mine will all have been numbered.

I would like to have you come home Saturday if you cannot before. The weather is so unfavorable, I suppose it will be difficult for you to come. But you will have to learn to brave all kinds of weather. Do write me often. If you should get any money, you may get me a dress off of this piece of calico unless you can find some black checked gingham. I can do better here in getting worsted goods. Can get a better piece off Coburgh for 3 shillings than that you sent up. You may get 10 yards of the calico. I would do it if they would give good measure or 9 and a half.

Andy Grove was here to see you on Friday about some tools. Wants to pay you in wood. Has laid out such tools as he wants and wishes you to set a price on them. The children are well.

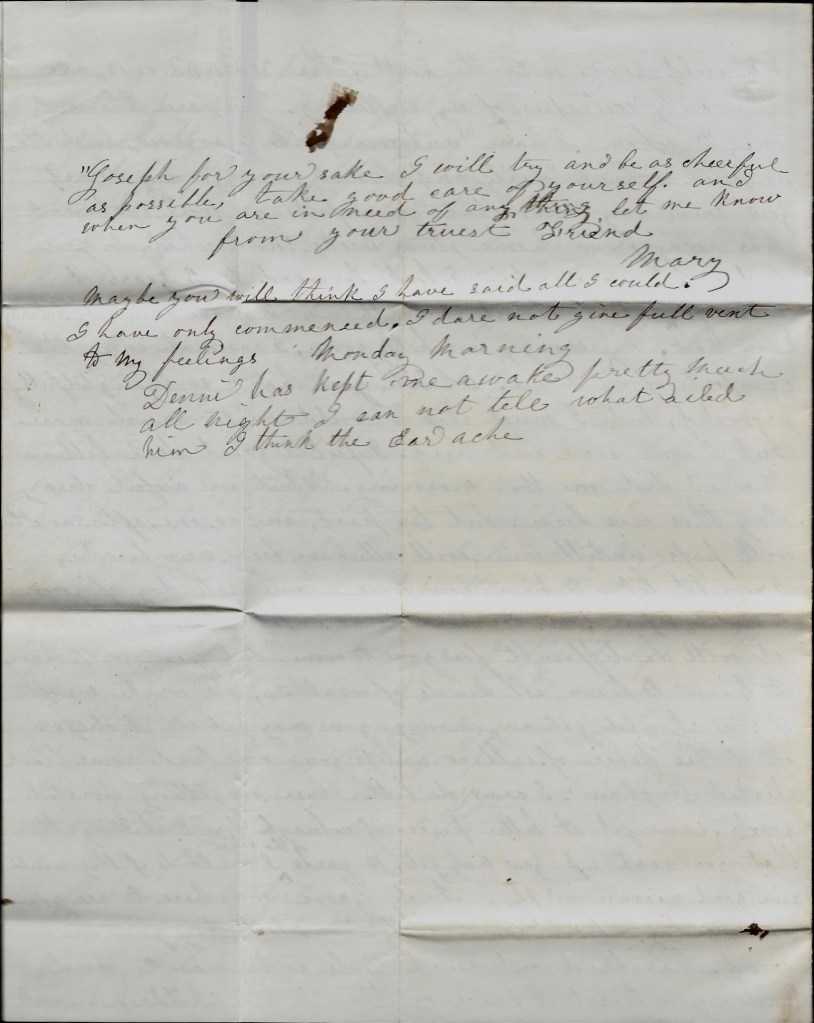

Joseph, for your sake, I will try and be as cheerful as possible. Take good care of yourself and when you are in need of anything, let me know. From your truest friend, — Mary

Maybe you will think I have said all I could. I have only commenced. I dare not give full vent to my feelings.

Monday morning. Denni has kept me awake pretty much all night. I can not tell what ailed him. I think the earache.

Fascinating letter,well written by a lovely , educated woman that expresses the concern and tribulations of mid nineteenth century life.Great read and God Bless the entire family…

LikeLike