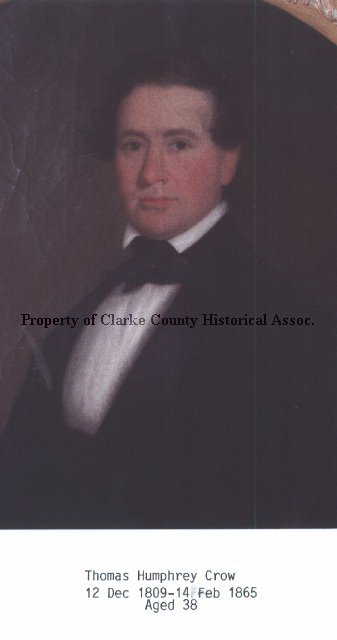

When the Civil War began in 1861, 51 year-old Thomas Humphrey Crow (1809-1865) was a prominent merchant in Berryville, Clarke county, Virginia. He had been married to Frances Amelia Shepherd (1811-1879) for nearly thirty years and their youngest child was at least ten years old. His oldest living son was Henry Clay Crow (1846-1865). But the war disrupted Thomas’s household and the lives of most of their neighbors. Union and Confederate troops passed through, bivouacked, and fought in Berryville so many times that by 1865, the town was in ruins.

Thomas was too old to pick up a musket himself but he led the county’s war effort by serving as the Chief Commissary, collecting taxes from its citizens to procure arms, tents, wagons and provisions for the volunteers who offered their services to the State of Virginia—one of whom would be his 16 year-old son Henry Clay Crow (1846-1865). Of course these commissary duties that Thomas engaged in were considered “treasonous” by the U. S. Government (having never recognized the Confederate States of America) and he was eventually rounded up with other “traitorous” citizens and sent to Fort McHenry where he was held until December 1862, 1 probably with an admonition not to engage in further such activities.

Thomas must have continued to wear on Gen. [Robert H.] Milroy like an ill-fitting shoe, however, for the following order—issued just a month before the Battle of Gettysburg—informs us that from his headquarters in Winchester, Gen. Milroy decided to have Thomas and his family exiled further “South.” Apparently he didn’t care where so long as he was gone from the district he was responsible for.

I haven’t learned where Thomas took his family but he did not live to see war’s end. He died on 14 February 1865 at the age of 55 and was buried in the Grace Episcopal Church Yard in Berryville. Census records indicate that Thomas owned 9 slaves prior to the war.

Transcription

Headquarters 2nd Vision, 8th Army Corps

Winchester, Virginia

June 2, 1863

Colonel,

You will send Mr. [Thomas H.] Crow living in Berryville through the lines immediately with his family. Send then South not to return during the war, under pain of being treated as deserters.

They will be permitted to take such articles of apparel and furniture as will be necessary to their comfort. A guard will be placed over the house and furniture left to prevent its being destroyed or removed until the Government Agent comes to receive it. An inventory must be taken of the effects left.

By command of Maj. Gen. Milroy

(signed) Jno. O. Cravens, Maj., & A.A.G.

Col. A[andrew] T[homas] McReynolds, Commanding 3rd Brigade

Headquarters 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, 8th A. C.

Berryville, Va., June 2nd 1863

Official Jas. H. [ ], AAAG

1 It’s not clear when Thomas Crow was arrested and taken to Fort McHenry but a newspaper notice appearing in the Alexandria Gazette on Friday, December 12, 1862, states: “By order of the Secretary of War, Thomas H. Crow and William H. Carter, citizens of Berryville, Clarke county, Virginia, have been released from Fort McHenry and returned to their homes.”

It isn’t treason to defend your home.

Tom

LikeLike

But the US Govt. never recognized the CSA and so Henry was considered to be raising arms to fight his own government—a “treasonous” act in the eyes of the US Govt. Virginia and the other states were considered to be in “armed rebellion.” Of course your opinion may vary.

LikeLike

Well, sure, but its much more than that, isn’t it? Secession – then and now – was not prohibited by statute or Constitutional provision. The act of secession in itself is not an act of treason. Maj-Gen. Robert H. Milroy was from Indiana. Crow was a resident in Berryville, Virginia. Clearly, Milroy was the invader, not Crow. Crow resisted the invader, as best he could. In this case, Milroy was the worst. It took little for Maj-Gen. Milroy to over-react. He occupied the nearby town of Winchester for months in 1863.

Maj-Gen. Milroy exiled “scores” of families, sometimes simply for voicing support for the Confederacy, sometimes for more tangible support of the Confederates. But, since many young men from the Shenandoah Valley were serving in the Confederate army, it is hardly surprising that the locals would support some Confederates. Milroy was said to have exiled the Logan family from their home because they “harassed” a Jessie scout. A Jessie scout was a Union soldier who would dress as a Confederate to gain information. But, the townspeople believed he truly exiled the Logans, because his wife wanted their house. “Exile” in Milroy’s practice meant they would take the family some 20 miles from town and deposit them to find their own way. “Treason” in Crow’s case likely meant he simply annoyed Milroy in some way.

Maj-Gen Milroy issued this order for Crow just a couple of weeks before Milroy allowed himself to be surrounded and forced to make a disastrous retreat.

Tom

LikeLike