This incredible and lengthy letter provides us with a vivid account of Fort Monroe, Yorktown, and Williamsburg from the perspective of a female civilian who was a native of Virginia and held strong secessionist views. Her name was Allie Catesby Jones (1836-1874) and I feel confident she was the same woman by that name who would later become the wife of Caleb Clapp Willard (1834-1905), possibly her cousin. Caleb, the son of Joseph and Susan (Dorr) Willard, was born in Vermont but came with his family to Washington D. C. about 1850. His older brothers, Henry and Joseph C. Willard, were then the proprietors of the Willard Hotel. After attending Washington Seminary, Caleb was schooled in the hotel business and sent, for his first assignment, when he was but 19 years old, to take charge of the Hygeia Hotel at Old Point Comfort which had a capacity of 1,000 guests and was the only summer hotel south of New York.

A yellow fever epidemic closed the hotel in the 1850s for a time but Caleb returned to partner with John Segar to purchase it and he had the exclusive management of the hotel until 1862 when the government ordered the hotel to be torn down because it interfered with military and naval operations. According to his obituary, Caleb was offered the privilege of superintending the destruction of the building which took two weeks. He then stayed on as a commissary storekeeper until 1864 when he went back to Washington, purchased the Ebbitts House, and became one of the wealthiest men in the District of Columbia.

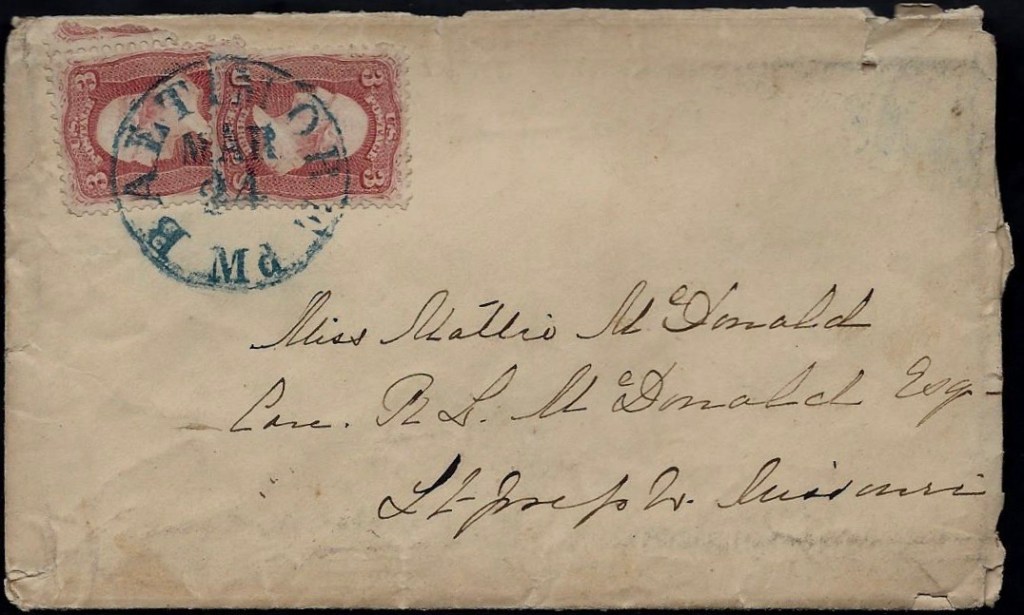

I’m not certain of Allie’s parents but I believe she was the 13 year-old child named “Alice Jones” residing with Joseph and Catharine Weisiger in Hampton, Virginia, in the 1850 US Census. From her letter we learn that just prior to making the trip to Fort Monroe where this letter was datelined, she was living in St. Joseph, Missouri. She was married to Caleb on 8 September 1863 and the couple had two children, Katherine Dorr Willard who was born on 19 November 1864, and Walter Jones Willard born 1 December 1868.

Transcription

Near Fort Monroe

March 22nd 1863

My dear friend,

There has not been an hour since I left you but my promise to write you has come up before me & I have not intended or wished to defer it so long. I have though been in one constant whirl of excitement & confusion & I did not think I could bring order out of such confusion & write such a letter as i should desire or you deserve. I am very far from being settled here now but my anxiety to hear from you all prompts me to write at all hazards. I need not tell you of our journey homeward—it consisted of the usual (no, I think ours was very unusual) amount of railroading, omnibus, shaking steam boating, & hotel stopping, of sight-seeing & shopping. So it was after being through all, after many tears and much sorrowing at leaving all all in dear St. Joe. we arrived in Baltimore on the Thursday following.

After we left Missouri, I sent a card to one very dear friend & she came at once to see me. We went shopping & such a world of lavishly beautiful goods—enough to make ones mouth water. Silks of the loveliest hues, laces fine as webs, & delicate as frost [ ] flowers which look as if they did have an odor—everything so tempting & such fabulous prices. I purchased a handsome black silk only and took to my friend Miss Fall’s, dressmaker. She only took a few measures and came out with the dress lining, fitting to perfection. I left the dress with her. I will give you an idea how fashionable dresses are made. It has four quillings, not flounces, on the shirt confined with velvet. The waist is plain. Two [ ] in front a deep point behind….Silks are very high $4.50 & 5.00 per yard.

After doing my shopping and seeing the secesh—and by the way, one of my purchases was a tiny gold microscopic view of Mr. Davis, Jackson, Bragg, Price, Lee, Morgan, Semmes & Beauregard—I left on Saturday evening and then was on the lovely Chesapeake, one side of whose waters have the shores of “My Maryland,” the other my own Virginia. We came down the bay in the lovely steamer Adelaide whose facsimile you have seen in my picture of Fort Monroe & we arrived at the fort on Sunday morning, three weeks ago today. Mr. Willard’s carriage was there for us & we came over to the Hotel—one of the loveliest places you can imagine.

This morning I just wish I had you here to examine the scenery. Fort Monroe is just a few hundred yards distant with its high stone walls & grim war dogs with the mouths pointed inland. The blue waters sparkle & dance in the sunlight. The first harbingers of spring are singing—the trees in foliage—a few flowers blooming, and everything looks bright & cheerful. But then I turn & look from another window into the country. Here lie fertile fields a waste, trodden hard by the vandals instead of growing crops, dotted all over with pitched tents, negro huts, no enclosure of any kind, lovely homes desecrated & occupied by the vandals. Many the tears I’ve shed over the desolations of my home. I find some friends here who being unable to leave have taken houses in the country. Everyone is glad to see me & this somewhat compensates for the regrets I had at leaving you all.

I have not been idle since coming here. Sister and myself & our Coz [cousin] procured a Pass from our “Old Massa”—Gen. Dix—and started to Williamsburg to see our old Aunt & her family. Coz Williard went so far as Yorktown with us. We went on a splendid steamer & arrived at Yorktown—the famous Yorktown—in the afternoon. There we procured another pass and walked around the fortifications—the same our brave Southerners had created. These were the same battlements over which the flags of our Young Confederacy had waved—the same paths where their feet had trodden—the same bold road which they had jogged upon. I must confess a thrill of joy shot through me as I remembered our Davis was here & his brave followers. I went to the house in which the “war council” was held when Davis and Lee said, “We can’t fight here, Magruder.” & he replied, “If I can’t whip them here, I can’t anywhere.” I took a piece off a tree from the yard, a piece at the gate through which they passed, and as bush overhung the gate, no doubt it has been touched by the sacred garments of our generals. We surveyed the place & after getting a few relics, returned to the boat where we remained all night.

Early next morning we took an ambulance kindly loaned by one of Gen. Keyes’ staff officers, & bidding Mr. Willard adieu, we started for Williamsburg—12 miles distant by the same road over which McClellan’s grand army pursued. I can’t describe my feelings as we passed through forests which I knew had echoed the tread of my friends over bridges which I knew had borne them. All along the road were entrenchments which my friends had thrown up—some only to mount one cannon & that to command the road.

After riding 10 miles we came to the battle ground, to “Fort Magruder”—only 3 miles from Williamsburg. Here stood the same fort but also how changed—not in outer appearance but in occupants. There lay the battlefield stretched out before me—trees shattered by cannon ball & everything quiet, as if no shrieks of dying men had risen from the earth. There is no vestige of the bloody conflict left—only a few large mounds beneath which lie some of our best men. We passed near enough to Fort Magruder to get some leaves from a tree on the parapet. We rode on and soon came in sight of the antique town, the first Capitol of Virginia. I did breathe freer to feel I was only a few miles from our capitol. Williamsburg is only about 80 miles distant.

As we passed through the streets, everything was familiar & here we see the splendid old Manor Houses built of imported brick, with high gable roofs, small windows, circular stone steps and mahogany stairways, large halls and [ ] so ancient and aristocratic one almost looks [ ]. Ladies in stiff, rustling brocades & gentlemen in shorts & powdered hair, descending the steps and promenading the halls.

We found our dear old Aunty’s family well—herself and two daughters. Our boy Jim to the wars. They have a fine large comfortable & well furnished house & plenty to eat, but everything so high. In them we saw secessionists indeed. I can’t hold a light to them & I cannot wonder when they tell us the outrages. They were in Williamsburg the day of the battle. Our army was retiring towards Richmond & the rear guard fights the battle. They tell me how our poor wounded were brought injured to the Ladies to care for. My two cousins went out & took two poor fellows to their home—almost every house had someone wounded in it. The churches were filled.

Our army left their wounded in Williamsburg & of course the Yankees coming in & taking possession found them. The Ladies of the place took linen sheets and pillow cases, fine bandages & everything for their comforts to them and carried everything for them to eat. Our wounded were badly treated by the Yankees. In the old church yard are about 60 graves, each one labeled. On each one is grown over with flowers and evergreens & hung with fresh wreaths everyday which tells the vandals who now possess the soil that they can never quench the spirit of the woman.

We went out to see the town. There stands, fast falling to ruin, our “William & Mary College” where some of our bravest officers & men have received teachings. The college was burned by the Yankees 1 —now the blackened walls alone are there—no professors, no pupils. I took a piece of slate from the roof. In front of the college on the green is a splendid statue of Sir Norborne Berkeley, Gov. of the colony. This statue which has stood for years & never been defaced by her sons, is now shattered by her invaders, the hands broken off, the form defaced. 2

We go then to the “Lunatic Asylum” and here I saw the first genuine Confederate persons I’d ever seen. A Capt. Jeffreys, CSA. The lunatics are still there & though our people wish to take care of them, the Yankees won’t allow it. Capt. Jeffries was wounded in the Williamsburg battle & has never been well enough to move. He is so handsome and so warm-hearted. All of the old families are in the town & are very bitter against the Yankees. There are the Tuckers, the Southalls, the Douglasses, Wallers, Byrds & other of the FFV [First Families of Virginia]. There are no men in the town—only a few lazy villains who want to stay at home & enjoy after awhile the liberty our brave men are periling all for. The young ladies scorn them and call them Jeff’s girls, send them tiny articles of ladies wearing apparel. nibs, napkins, &c.

The Yankees say “the women of Williamsburg ain’t afraid of the Devil himself.” They tell me when the Confederates retreated through Williamsburg, the air was rent with sobs and cries of the ladies. As they would pass, they’d take off hats and say, “Goodbye ladies. God bless you. We hate to leave you.” and the girls cried themselves sick in bed. Sad the day, all tell me, to have them go & then have the despicable wretched come in. One yankee rode up to my cousin’s front window where she stood & pointed a pistol at her head. She ran from him & he followed on horseback [as she went from ] the house into the garden. She ran and he pursued until finally she dropped from fear and exhaustion and he then went off. Everyone has tales of horror to tell. We remained one week, visited all the noted places and came home laden with relics.

I must tell you of the late Confederate raid. Three weeks since one morning a body of rebels came in town. The Yankees fled as they came through. All the doors and windows long closed were opened & the ladies, old & young, welcomed them. The men said, “Good morning, ladies, how are you? You are looking very well considering the bad company you’ve been in.” Ladies asked, “Where are the Yankees? We are looking for them. Tell us where they are?” And all such fun. Tis said the Yankees ran away so fast, they did not ever mount their horses. We had a delightful visit & enjoyed the secesh talk. I heard on Sunday prayers for the “President of the Confederate States” & a southern sermon at the house of the Reverend Mr. [Thomas M.] Ambler, his church having been closed. 3

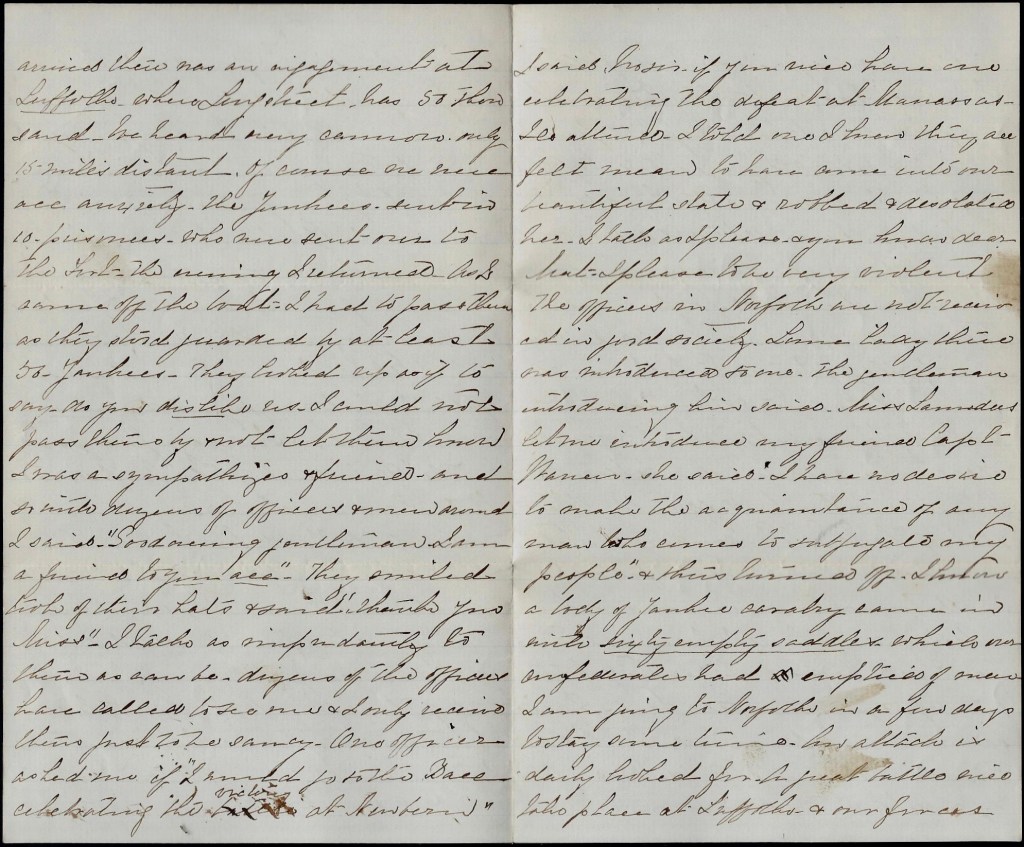

Since our return, I have been up to Norfolk to see my Mother’s family—such delight you never saw. They complain bitterly of the evacuation. I saw the obstructions in the harbor & all the forts around. Everything is quiet on the city but on the day after I arrived, there was an engagement at Suffolk where Longstreet has 50 thousand. We heard heavy cannon only fifteen miles distant. Of course we were all anxiety. The Yankees sent in 10 prisoners who were sent over to the Fort the evening I returned. As I came off the boat, I had to pass them as they stood guarded by at least 50 Yankees. They looked as if to say, do you dislike us? I could not pass them by and not let them know I was a sympathizer & friend and so with dozens of officers and men around I said, “Good evening gentlemen, I am a friend to you all.” They smiled, took of their hats, and said, “Thank you Miss.” I talk so impudently to them as can be—dozens of the officers have called to see me & I only receive them just to be saucy. One officer asked me if I would go to the Ball celebrating the victory at Newbern. I said, “No sir. If you will have one celebrating the defeat at Manassas, I’ll attend.”

I told one I knew they all felt mean to have come into our beautiful state and robbed & desolated her. I talk as I please & you know, dear Mat, I please to be very violent. The officers in Norfolk are not received in good society. Some lady there was introduced to one. The gentleman introducing him said, “Miss Saunders, let me introduce my friend, Capt. Warner.” She said, “I have no desire to make the acquaintance of any man who comes to subjugate my people!” and thus turned off. I know a body of Yankee cavalry came in with sixty empty saddles which our Confederates had emptied of men. I am going to Norfolk in a few days to stay some time. An attack is daily looked for. A great battle will take place at Suffolk & our forces victories will push on to Norfolk. Semmes has sent to the President today. He must have a port opened to take his valuable prizes to and Norfolk must be the one. An attack is daily looked for here. Batteries are moved. Gunboats in readiness & our Merrimack is dreaded. I hope to see the fight. I have seen some 50 prisoners sent by flag of truce to Richmond.

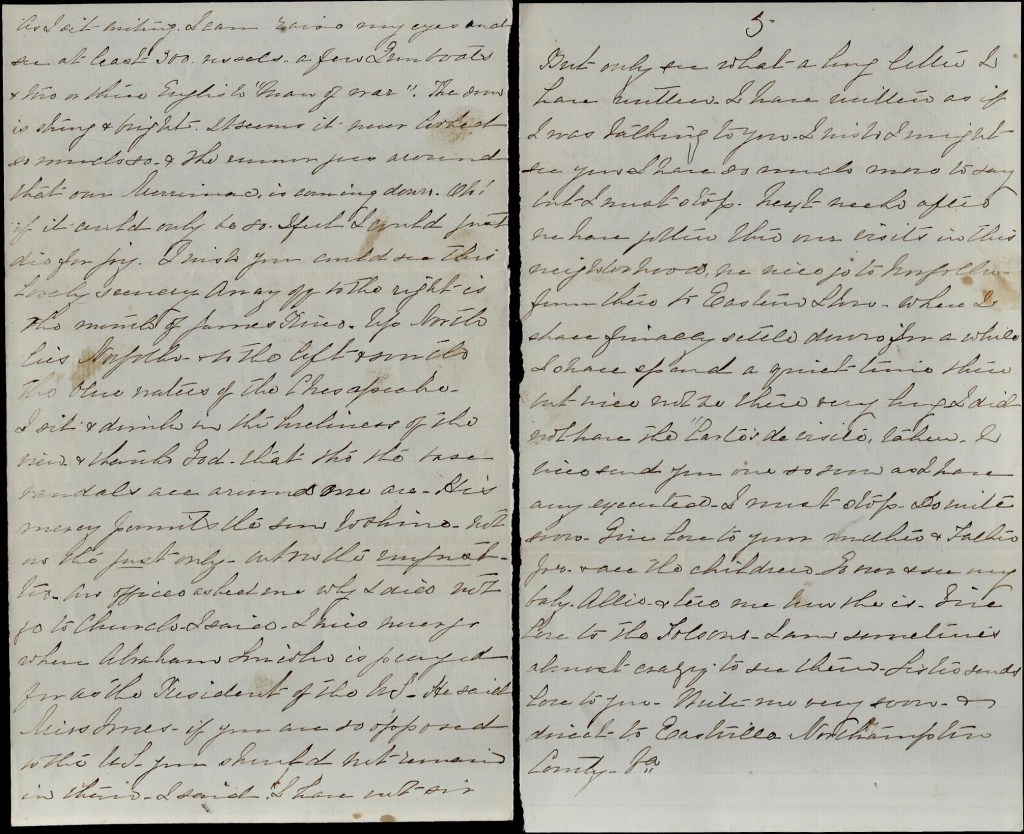

Your letter is too voluminous. It can’t fly twice but my brother in Norfolk tells me he can send a letter to Greensboro without difficulty. They talk of the USRR “underground railroad as if it was a fixed institution. I have seen several letters from the rebel army since I arrived. We are not ready yet to give up & prisoners tell me Davis scorns a compromise. Don’t believe newspaper stories. We are well off and determined as ever. But only see what a long letter I have written. I have written as if I was talking to you. I wish I might see you—I have so much more to say but I must stop.

Next week after we have gotten this our visits in this neighborhood, we will go to Norfolk [and] from there to Eastern Shore where I shall finally settle down for awhile. I shall spend a quiet time there but will not be there very long. I did not have the “carte-de-visite” taken. I will will send you one as soon as I have any executed. I must stop. Do write soon. Give love to the Folson’s. I am sometimes almost crazy to see them. Sister sends love to you. Write me very soon and direct to Eastvilla, Northampton county, Virginia.

As I sit writing I can raise my eyes and see at least 300 vessels, a few gunboats, and two or three English “Man of War.” The sun is shiny and bright. It seems it never looked so much so & the rumor goes around that our Merrimack is coming down. Oh! if it could only be so. I feel I could just die for joy. I wish you could see this lovely scenery. Away off to the right is the mouth of James river. Up north lies Norfolk. To the left & south the blue waters of the Chesapeake. I sit and drink in the loveliness of the view & thank God that though the base vandals are all around me, His mercy permits the sun to shine, not on the just only, but on the unjust too.

Two officers asked me why I did not go to church. I said, “I will never go where Abraham Lincoln is prayed for as the President of the U. S.” He said. “Miss Jones, if you are so opposed to the U. S., you should not remain in them.” “I have not, sir, I am in the Confederate States. Virginia is one of them & I think it best for invaders to leave & let those [alone] who will build her up.” I am going out for a ride this afternoon along the whitest and loveliest of shores. Again let me beg you to write soon. I am with all love and a kiss in my heart for you. Your affectionate friend, — Allie

I send you a piece of lox from the yard of the Nelson house where the Council of War was held & a piece from Fort Magruder. The first one at Yorktown. The last at Williamsburg.

1 The Wren (or Main) Building of the College of William & Mary was burned in September 1862, the fire started by Union soldiers from the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry in retaliation for the surprise raid and capture of the provost marshal.

2 In 1797 the President and Professors of the College of William & Mary purchased the statue for $100. It was removed to the College in 1801, partially repaired, and placed in front of the Sir Christopher Wren Building in the College Yard, where, as a student of the day commented, “it cut a very handsome figure indeed.” There it remained for 157 years except for a brief period during the Civil War when it was placed for safekeeping on the grounds of Eastern State Hospital. [William & Mary Special Collections]

3 Rev. Thomas M. Ambler served the pulpit in the Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg. His church was ordered closed in February 1863 by the provost marshal when Ambler refused to pray for the President of the United States.

Amazing reading…amazing woman…

LikeLike