The following letter was written by William Henry Anderson (1836-1902), the son of Francis D. Anderson (1807-1866) and Jane Davidson (1808-1880) of Londonderry, New Hampshire. William attended primary school in Londonderry, before studying at the Pembroke Academy (Pembroke, New Hampshire, 1852-1853), Phillips Academy (Andover, Massachusetts, 1853), and Kimball Union Academy (Meriden, New Hampshire, 1854-1855). He considered attendance at Dartmouth, favoring instead Yale College, which he entered in 1855. An 1857 disciplinary action notwithstanding, Anderson graduated in the spring of 1859. [See: The Demise of the Crocodile Club: A Town/Gown Tragedy at Yale]

After graduating from Yale College at New Haven, Connecticut, William accepted a job as a private tutor on the Sligo Plantation near Natchez, Mississippi, teaching students from Sligo as well as the nearby Retirement Plantation from 1859 to 1860. Prior to the Civil War, it was a widespread practice for a wealthy southern planter, or planters banding together, to hire a college graduate from the North to teach the white children on the plantation. Public schools were virtually non-existent in the South. By the late 1850s planters monitored the schooling closely to make certain that tutors from the North did not attempt to introduce ideas about racial equality into the heads of their children.

During his time in Mississippi, William wrote numerous letters home to his parents and to his future wife Mary A. Hine. He arrived at Bennett’s Retirement Plantation in early September 1859, and shortly thereafter settled in at David P. Williams’ Sligo Plantation. In his letters from Natchez archived at the University of Michigan, William described his relative isolation, loneliness, teaching and wages, corporal punishment, thoughts on slavery and the enslaved men and women on the plantation, games he played with his scholars, travel between the Sligo and Retirement plantations, and leisure activities such as hunting and horseback riding. In late December 1859, he provided a lengthy description of a (largely) steamboat trip to New Orleans with his students for Christmas.

Anderson noted that no poor white people lived between Sligo and Natchez; he was uncomfortable with the aristocratic lifestyle of white people living in the south, and expressed this view on multiple occasions in his correspondence (see especially September 30, 1859). Although his father appears on list of members of the American Anti-Slavery Society, William H. Anderson did not write with disgust at slavery, but rather used racist epithets, accepted the “servants” who assisted him in various ways, and wrote unmoved about abuse doled out to children (see especially June 9, 1860). In one instance, he wrote about enslaved women who gathered near to the house in the evenings before supper to sing and dance (October 25, 1859). One of the highly detailed letters in the collection is William H. Anderson’s description of the use of the cotton gin on the Sligo Plantation, which includes remarks on its history, its functioning, the various jobs performed by enslaved laborers, and the rooms in which the jobs took place. He included calls made by enslaved workers between floors of the “gin house” and the roles of elderly men and women in the grueling labor (October 1859). In 1860, Anderson planned to take a summer break in Tennessee and then teach another year, but on the death of his oldest scholar Susie (14 years old) by diphtheria, Williams decided against having a school the next year (July 4, 1860).

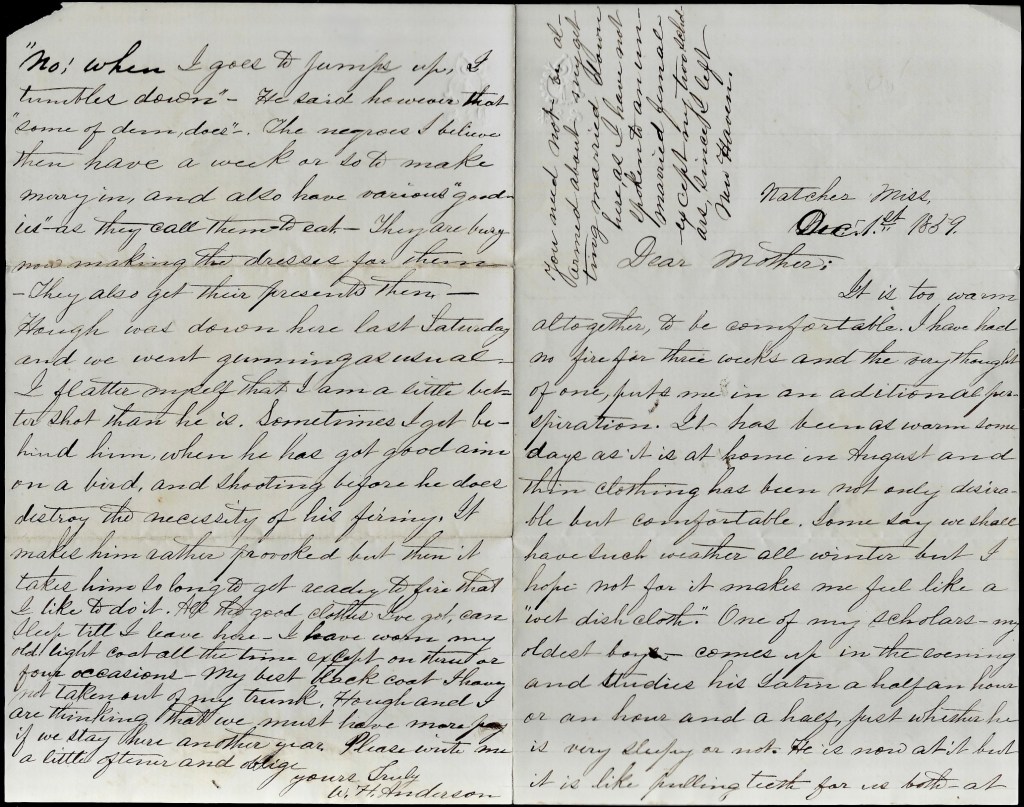

Transcription

Natchez, Mississippi

December 1st 1859

Dear Mother,

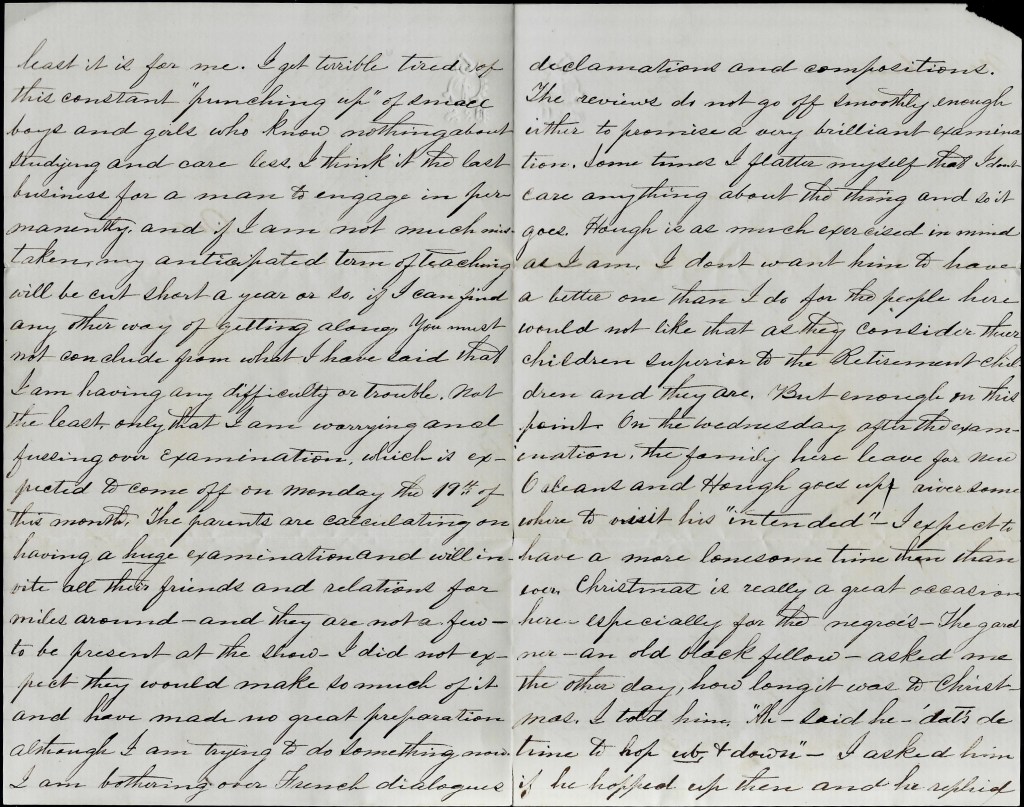

It is too warm altogether to be comfortable. I have had no fire for three weeks and the very thought of one puts me in an additional perspiration. It has been as warm some days as it is at home in August and thin clothing has been not only desirable but comfortable. Some say we shall have such weather all winter but I hope not for it makes me feel like a “wet dish cloth.”

One of my scholars—my oldest boy—comes up in the evening and studies his Latin a half an hour or an hour and a half just whether he is very sleepy or not. He is now at it but it is like pulling teeth for us both—at least it is for me. I get terrible tired of this constant “punching up” of small boys and girls who know nothing about studying and care less. I think it is the last business for a man to engage in permanently and if I am not much mistaken, my anticipated term of teaching will be cut short a year or so, if I can find any other way of getting along.

You must not conclude from what I have said that I am having any difficulty or trouble. Not the least. Only that I am worrying and fussing over examination, which is expected to come off on Monday the 19th of this month. The parents are calculating on having a huge examination and will invite all their friends and relations for miles around—and they are not a few—to be present at the show. I did not expect they would make so much of it and have made no great preparation although I am trying to so something now. I am bothering over French dialogues, declamations, and compositions. The reviews do not go off smoothly enough either to promise a very brilliant examination.

Sometimes I flatter myself that I don’t care anything about the thing and so it goes. [Joel Jackson] Hough is as much exercised in mind as I am. I don’t want him to have a better one than I do for the people here would not like that as they consider their children superior to the Retirement children and they are. But enough on this point.

On the Wednesday after the examination, the family here leave for New Orleans and Hough goes up river somewhere to visit his “intended.” I expect to have a more lonesome time then than ever.

Christmas is really a great occasion here—especially for the negroes. The gardener—an old black fellow—asked me the other day how long it was to Christmas. I told him. “Ah,” said he, “dat’s de time to hop ub & down.” I asked him if he hopped up then and he replied, “No! when I goes to jumps up, I tumbles down.” He said, however, that “some of dem does.”

The negroes, I believe, then have a week or so to make merry in, and also have various “goodies” (as they call them) to eat. They are busy making the dresses for them. They also get their presents then.

Hough was down here last Saturday and we went gunning as usual. I flatter myself that I am a little better shot than he is. Sometimes I get behind him when he has got good aim on a bird, and shooting before he does, destroy the necessity of is firing. It makes him rather provoked but then it takes him so long to get ready to fire that I like to do it. All the good clothes I’ve got can keep till I leave here. I have worn my old light coat all the time except on three or four occasions. My best black coat I have not taken out of my trunk. Hough and I are thinking that we must have more pay if we stay here another year. Please write a little oftener and oblige.

Yours truly, — W. H. Anderson

You need not be alarmed about my getting married down here as I have not spoke to an unmarried female except my two scholars since I left New Haven.