The following letters were written by Joseph Litchfield Locke (1841-1899) of Co. I, 33rd Massachusetts Infantry. Joseph was the son of Rev. William Sherburne Locke (1808-1896) and Caroline Dame Tibbets (1809-1893).

According to his obituary, appearing in The Inter Ocean of 17 July 1899, Joseph was born in Canada in 1843 and came to Chicago twenty-five years ago. He was a member of the firm J. L. Locke & Co., cap manufacturers, at No. 254 Monroe Street. During the war, Mr. Locke served as a lieutenant in the 33rd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, gaining his promotion from the ranks by gallantry on the field. He was a charter member of the Menoken club. A widow, two brothers, and two sisters survive him. His brothers are Judge James [William] Locke of Jacksonville, Florida, who has been on the U. S. Supreme Court bench for many years, and Eugene O[lin] Locke, clerk of the United States Supreme court [should be the US District Court of the Southern District of Florida] in the same city.”

Joseph’s military record informs us that he mustered in to the regiment as a corporal in early August 1862. He was promoted to sergeant in early March 1863, and commissioned a lieutenant in September 1864. He mustered out of the regiment on 11 June 1865 at Washington D. C.

[Note: These letters are from the private collection of R. J. Ferry and were transcribed and published on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Related Reading:

Civil War Lowell: 33rd Massachusetts infantry. RichardHowe.com Lowell Politics & History, May 30, 2011

Letter 1

Camp near Stafford Court House, Va.

February 20th 1862 [should be 1863]

This sheet of paper is rather dirty and soiled but soldier’s things will get so & it must go. We are in our new houses, there being 14 for the company and five in each house. Their dimensions are as follows: 12 feet long, 6 wide, walls 4 feet high. Facing the street the door and fire place occupy the whole end. Our bunks are crossing at the rear, the lower one 6 inches from the ground, upon which 3 lie, the upper one 2.5 feet above that. They are made of small poles laid across larger ones and covered with boughs. Our fireplace is built up of sticks laid up in Virginia mud and lined with ditto two or three inches thick which bakes as hard as a rock—a perfect brick in a short time.

There is one piece of good news to me and will probably interest you. My friend Jacob Aling has received an appointment to the Military Academy at West Point and received his discharge and gone home. I was sorry to have him leave but am glad for his part. He is a young man who will make his mark.

I received a letter yesterday from home saying you would get my box off before long. Yes, I have received my old stocking, a lot of postage stamps, the paper in a paper besides a number of other papers which are very agreeably received in this out of the world place. I haven’t much of anything new to write and have a number of other letters to write. I got Letta’s letter and was glad to hear from her and to see that she can write some if not in writing letters.

I write to Gene and give him a talking to when I get time. Why doesn’t he like Mr. Wheeler? I’m most afraid the fault is a good deal on his own part. Ask any questions about soldier’s life, military affairs, &c. that any of you would like to know & I’ll try to give you what information I am able on any subject.

[Shoulder straps sketch]

We were reviewed a few days ago by General Hooker, Sigel & a number of other Major Generals were present.

Letter 2

The 33rd Massachusetts Infantry, part of the XI Army Corps, arrived on the field at Gettysburg on the first day of battle. Most of the XI Corps was deployed north of Gettysburg in an attempt to hold the Rebel advance in check. However, two brigades of the Corps (von Steinwehr’s Division), which included the 33rd Massachusetts, were ordered to remain on Cemetery Hill as a reserve to support the Federal artillery being placed there. For details of their actions over the course of the battle, see 33rd Massachusetts Infantry at Gettysburg by Patrick Browne posted on Historical Disgression on 11 May 2013.

Battlefield of Gettysburg, Pa.

July 3d 1863

Dear folks at home,

We are into it tough and tight. We arrived here the p.m. of the 1st. Part of our Corps was in. Our Brigade laid on a hill supporting a battery and were only shelled some. There were but two Corps in on the first against the whole number of rebs. Yesterday a.m. was mostly taken up getting positions. We shelled them some but could not draw any fire from them till about 3 p.m. when they opened on us and attacked us on the left with great force, but we held them there, held our position, and repulsed them with greater slaughter.

Just as the hardest fighting on the left, our extreme right held by the 12th Corp & our Brigade of the 11th was attacked by Ewell’s entire force, massed, and they seemed determined to force our position & turn our flank. Had they done it, it would have been all up with us but we held it handsomely & being reenforced by the 6th Corps about 6, kept our position & repulsed them & small [loss] to us as we were in good rifle pits. Our regiment has had quite a number killed and many wounded. ‘Tis uncertain how many.

I have remained with and helped the Surgeon of our regiment. We were (and are) in a stone barn a short [distance] to the rear of the regiment. Shell and shot are falling thick and fast around the barn [and] a number have struck it. 1

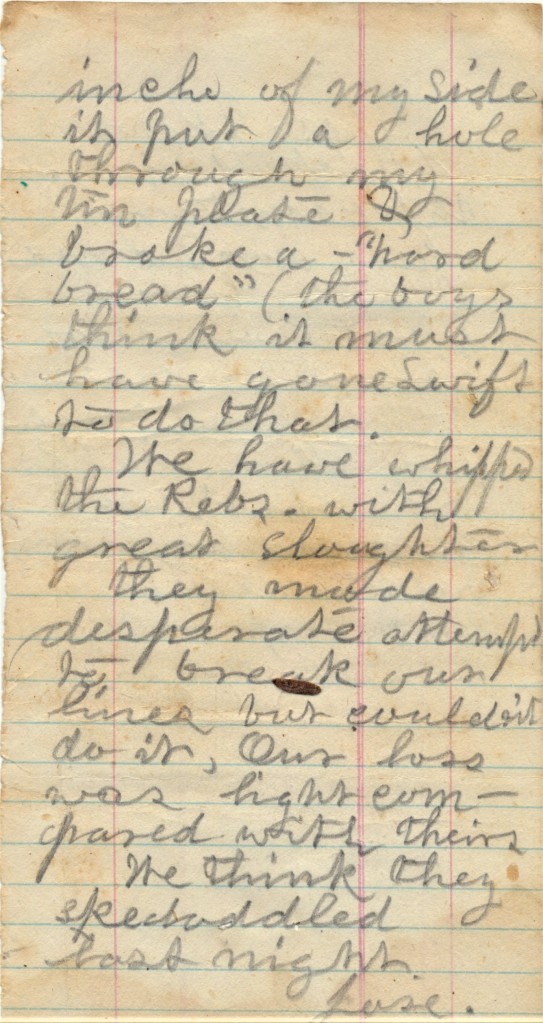

July 5th, 10 a.m. Since writing the last, I have been with the regiment & under some hot fire. Have probably had 50 men wounded & killed. I got a bullet through my haversack & blankets yesterday within an inch of my side. It put a hole through my tin plate & broke a “hard bread” (the boys think it must have gone swift to do that). We have whipped the rebs with great slaughter. They made [a] desperate attempt to break our lines but couldn’t do it. Our loss was light compared with them. We think they skedaddled last night. — Jose

These flowers I picked in the cemetery where some of our heaviest batteries were planted & which were used rough by them shells & which was charged by them and defended by our Corps in which was our regiment.

1 The XI Corps Hospital took over the George Spangler farm in the middle of the afternoon on 1 July 1863 and remained there through the next two days of fighting and for several days afterward. “The wounded soon began to pour in, giving us such sufficient occupation that from the 1st of July till the afternoon of the fifth, I was not absent from the hospital more than once and then but for an hour or two,” said 26-year-old Dr. Daniel G. Brinton, surgeon-in-chief, Second Division, XI Corps, U.S. Volunteers. “Very hard work it was, too, & little sleep fell to our share. Four operating tables were going night and day. Many of them were hurt in the most shocking manner by shells. My experience at Chancellorsville was nothing compared to this & and I never wish to see such another sight. For myself, I think I never was more exhausted.” A Spangler surgeon who was approaching total exhaustion called the work “too much for human endurance.”

The hospital would use almost every inch of that Pennsylvania bank barn. Dr. Brinton estimated that 500 wounded and dying men filled it. A hospital worker guessed 400. Men were crammed so closely together that they passed deadly infectious diseases such as typhoid fever to one another. Many men died of these diseases rather than the battle wound that brought them to the hospital. Pvt. Reuben Ruch, age 19 of the Easton area, 153rd Pennsylvania, said: “This barn was full of wounded men from one end to the other. Where there was room for a man you could find one. The hay mows, the feed room, the cow stable, the horse stable and loft.” The hospital grew to about 1,900 wounded on July 4-5 after the Confederates retreated and it was safe for ambulances to search on and around the battlefield for wounded men left behind. Even though the hospital served the XI Corps and its 26 regiments at Gettysburg, it hosted Confederate and Union wounded and men from more than 50 regiments altogether. Many Confederates were placed in the barn’s wagon shed to separate them from the Army of the Potomac wounded. The barn and other outbuildings quickly filled, so men were then placed in the open because not enough tents were provided after the battle.

“At the doorway I saw a huge stack of amputated arms and legs, a stack as high as my head!” said Pvt. William Southerton, age 21, 75th Ohio. “The most horrible thing I ever saw in my life! I wish I had never seen it! I sickened.” Wounded Pvt. Justus Silliman of the 17th Connecticut said, “The barn more resembled a butcher shop than any other institution. One citizen on going near it fainted away and had to be carried off.” [See Restored George Spangler Farm tells grim stories of Gettysburg dead and wounded.”]

Letter 3

Camp near Berlin Station, Virginia

July 12, 1863

Dear folks at home,

We are stopping here for a day. We may stay a little longer before recrossing into Dixie. We have expelled the invader from Loyal soil! Many blame Gen. Meade for not bagging Lee’s force. Such persons are no judges of military forces or movements. Often our best officers are wronged & that shamefully by reporters who can judge nothing of the movements of an army. ‘Tis well enough to talk of cutting off the retreat of the Rebs but ‘twoud have been risking too much to have divided our forces so as to have undertaken it. We only gained the victory at Gettysburg by holding a very short line and making the most of all of our forces and acting on the defensive at that.

We are about 5 miles below Harper’s Ferrry. (I don’t know where I wrote you last but when we left Gettysburg, we marched back through Emmettsburg on over the mountains to Middleton, back to South Mountain, through to Boonsboro, on to Hagerstown, where [we] waited two days and fortified expecting another fight, but the Johnnies ran away. The morning after they retreated, our Corps marched down to Williamsport, saw that they were all well across and returned coming on here through Hagerstown, Middleton & Jefferson.

I am in very good health. Have had a horse since the fight at Gettysburg. I “picked up” a good one there (“picked up” is a very significant word in the army and accounts for the possession of anything a person may have). This one is a very good horse. I was going off to get rations up to the regiment about 3 the morning of the 4th when I came across him loose on a part of the battlefield with a good bridle and saddle on so I mounted it. I picked up a horse at [the] Beverly Ford fight but he had been used hard & gave out at Centreville so I walked to Gettysburg.

This is a splendid country, here and up into Pennsylvania. It is one continuous wheat field. It was the finest view I ever had from the mountains we crossed near Middleton. Hagerstown is the finest place we have been in on the march (I didn’t see much of Frederick) and the men, women, and young ladies & children came out in great numbers to see us pass just as you would at home to see a circus pass, in the porer parts of the city. Many exerted themselves to keep pails and tubs full of water placed where we could snatch a drink as we passed in the more worthy part of the city. The ladies waved their handkerchiefs very gracefully as we passed. The best way to serve the soldiers on a march is to have plenty of fresh cold water where they can snatch a cupful without falling behind.

I suppose you have had good accounts of the battle at Gettysburg but I can give you an idea of where our corps & regiment laid.

Our position, you see, was supporting the batteries near us and Battery 1 & 2 doing considerable damage. A number of Reb batteries from points 3 and 4 opened on them, bringing us under a crossfire which was very severe. The worst of our loss was sustained here.

But the mail goes in a few minutes & I must close. Send me two skeins of black silk & a few needles in your next. Also a silk pocket handkerchief. — Jose

Letter 4

Bristoe Station, Va.

September 20, 1863

Dear folks at home,

We still remain at this place and probably shall for some time to come as our Corps is considerably scattered at present and we are doing duty which some one must do—viz: guard the railroad. Our Corps (what is here) now guards the railroad from Manassas Junction to the Rappahannock. One Division (the 1st) is at the siege of Charleston [and] one Brigade of our Division is in Alexandria.

I have been quite anxious lately for fear you did not receive my letter containing $50 in which I told about my box as I have not heard from you concerning it. We have received no boxes since the 10th inst. and I understand there is a lot of them now at Culpeper which will be sent here soon and probably mine is in it, if everything is right.

I got a letter from Gene a few days ago. He had not been there long but seemed to like.

We get but little news lately from anywhere but think everything is going on right. Our army has been for a long time and is now receiving great reinforcements. A great many conscripts besides over 30,000 men have lately returned from New York City who have been there from this army protecting and enforcing the law during the draft. We have received no conscripts and ’tis doubtful whether we get any for some time at least. Tis strange how a regiment will get reduced. Our regiment numbered (without the two companies which went into the 41st) 1,000 able bodied? men. We have had but few men killed in battle and we now draw rations for 461 men. Hardships pick off men faster than bullets. You may well believe that the most of the men we have now are tough.

Our regiment does a good deal of scouting now-a-days and under the direction of a boy 18 or 19 years old are quite successful. This young fellow (Doughty) came with the family when but five years old from the North somewhere so are good Union people. His father is in Richmond a prisoner. Young Doughty’s mother & sister live about 4 and a half miles from here. 1 He went as guide of a part a few days ago and alone took two cavalry Rebs prisoners and led our men to a house where there were 13 large trunks belonging to Reb officers and packed with their uniforms, &c. All of these our men opened and took everything out they wanted. There was a good deal of valuable property in them and our men came in loaded with booty.

We are having the weather very cool now and have had a long, cold storm for a few days past. Meg, postage stamps have “played out” as you may see by the envelope.

The bushwhackers are very bad and saucy around here. Not long ago they took a captain, five men and four horses—not long before they took Lieut. [Arthur C.] Parker of our regiment (he came out as Orderly Sergt. of Co. I) detailed on Gen. Meade’s staff as aide-de-camp. He visited the regiment, started off, and has not been heard from since. 2 They also took three teams out of a train of sutler’s wagons when the train was guarded by cavalry before & behind. They are very bold.

Write soon & I’ll let you know as soon as I get the box. — Jose.

1 My hunch is that the young man named Doughty was James R. Doughty (1842-1875), the son of Abraham Doughty (b. 1800) and Eunice Reynolds (180801872). This family came from New York to farm in Prince William county, Virginia, prior to 1850. After the war, James worked as a clerk in the Treasury Department for a time but in 1875 he was killed while working as a flagman on the Baltimore & Potomac Railroad when he fell under the wheels of the cars near Bowie Station. [Still need to verify his identity]

2 Arthur C. Parker was a 21 year-old student when he enlisted on 23 July 1862 as a 1st Sergeant in Co. I, 33rd Massachusetts. He was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant on 3 March 1863 and was killed by guerrillas on 16 August 1863 at Catlett’s Station, Virginia.

Letter 5

The following letter provides us with a riveting account of the 33rd Massachusetts’ participation in the Battle of Raccoon Ridge, Lookout Valley, Tennessee on 29 October 1863.

Camp near Lookout Mountain

November 3rd 1863

Dear Folks at home,

I wrote you a few lines the morning after the gallant charge and heavy loss of the 33rd [Massachusetts] on the 29th ult., but you of course would like to hear further particulars. I’ll tell you how we came here from Stevenson.

On October 24th, we marched back to Bridgeport, staid one night, and then marched across the river and went about five miles to Stuart’s Store where we staid till the morning of the 27th when we went on. About noon we stopped two hours at Shell Mound where is a very large cave. A small river runs out of it of splendid cool and clear water. It is as large as the one running from the Massebesic to the Merrimack at Goffs Falls. I went into it most a mile. Boats can go up the stream a good many miles.

We kept on and staid that night among the mountains and the next p.m. came in sight of Lookout Mountain, advanced, drove in the reb pickets & kept on but were soon opened on from the batteries on the mountain & they shelled us pretty sharp before we fell back. We lost Sergt. Adams of Co. F from Lowell here. He was killed on the spot. This was at “4” on the map. From here we fell back round the hills and marched on towards the river & went in camp at “10.” Here we all went to sleep quietly (excepting Companies A, B, & G which went off scouting so were not in the fight).

At 1 o’clock we were all [awakened by] firing about a mile off and soon we were turned [out] by the bugle and the regiment ordered off at double quick. The Chaplain & I followed hard after keeping close up to pick up any wounded. It was very dark—about 1:30 o’clock—and as we advanced up the hill in line of battle, there was some confusion and some of the officers thought the 73rd Ohio was partly ahead of us and when near the top of the hill, the adjutant hallowed and asked if the 73rd was ahead and the rebs cried out, “Yes! 73rd. Don’t shoot your own men!” and then gave us a terrible volley, wounding our Colonel, killing our Color Sergeant, and killing & wounding many more.

We then fell back to the road at the foot of the hill amid the shower of bullets. Here we formed anew, fixed bayonets, and steadily advanced under their heavy fire—reserving our fire till on top of the hill and then giving them the bayonet alone. This the rebs couldn’t stand but scattered like sheep and we went into their pits with such a yell as is only heard where a bayonet charge is made. We had only a part of two regiments in the charge, ours and the 73rd Ohio—not more than 500 men. But the rebs allow that they had five regiments with over 2,000 men. 1

The hill is about 200 feet high and very steep in most every place—45o—with a growth of oak and considerable underbrush. And the men went in with knapsacks & everything on & I didn’t see one thing thrown off. They didn’t know they had them on. The victory was ours but dearly won. I was at work hard all the time helping the wounded off and as it grew lighter, it was a sad sight to come across intimate friends dead and cold as they fell or just breathing their last.

Our adjutant—a young man almost idolized by every man in the regiment, two 2nd Lieutenants, and our Color Bearer all lay dead not far apart. We lost four officers killed and four wounded, 25 men killed, 56 wounded, and two missing—probably killed. None of the Normals were hurt. Our Colonel is very badly wounded but may recover.

I send you a rough map of the country as near as I could make it out. Also a rough sketch of the hill we took & Lookout Mountain beyond. By timing sound, we make it 1.75 miles from the top of Lookout [Mountain] to the top of the hill we are on. Lookout is impregnable from the front, being 1400 feet hight—very steep & a perpendicular wall or ledge all round the top.

Write soon & often. I got the letters but have not got my box but consider it safe and sure sometime. We are shelled every day from Lookout but they don’t do much damage.

1 Locke’s account squares well with Samuel H. Hurst, 73rd Ohio Infantry. “When we had approached within 2 or 3 rods of the enemy’s breastworks there opened upon us a most murderous fire from a force on our right flank, completely enfilading our line. The appearance of this force on our flank seemed to forbid our farther advance. I knew we had no support on our right, and we had not held communication with the 33rd Massachusetts at any time during the engagement. Regarding the Seventy-third as the directing battalion, I had paid no attention to our support on the left, and it was impossible for me to learn whether Col. Underwood was advancing or not, while heavy and irregular firing, with cries of “Don’t fire upon your own men,” coming from the left of our front, only increased the confusion. Under the circumstances I deemed it rash to advance farther until I knew that one, at least, of my flanks was protected. I ordered the regiment to retire a few rods, which they did in perfect order, and lay down again, while I sent Capt. Higgins to ascertain the position and movements of the 33rd Massachusetts. Learning that, though they had fallen back, they were again advancing, I was preparing to go forward also, when information came that the 33rd had turned the enemy’s flank, was gallantly charging him in his breastworks, and driving him from the left crest of the hill.”

Letter 6

This letter describes in detail the action of the 33rd Massachusetts and other regiments in their brigade during the Battle of Peachtree Creek that took place on 20 July 1864. It was a desperate hand-to hand struggle in which both sides incurred heavy losses.

Four miles north of Atlanta, Ga.

July 23rd 1864

We are still with the wagon train and have escaped one hard fight by being on duty at the rear—the first fight we have kept out of on the campaign. On the 20th inst. our Corps and one Division of the 4th Corps had a desperate open field fight. The Rebs under their new commander (Hood) made a charge on our lines intending to break them at all hazards. Our men were just forming after crossing a deep creek (Peachtree Creek). Our men were in one line of battle and had they been broken through they must have nearly all been captured but they rallied for a good position and met the Rebs with a terrible volley mowing them down and then there come a fight where every man fought on his own “hook”—loading and firing—or charging bayonets. Some used the butts of their guns ad others had it hand to hand.

A man in the 136th New York made for a color bearer—he was shot through the hand but kept on—knocked the color bearer down with the butt of his gun and brought the colors off 3 or 4 rods but was shot dead—when one of his comrades brought the colors safely off. 1

The 26th Wisconsin also captured a stand of colors 2 and 7 officers swords (from killed and wounded officers). With such fighting the rebels were repulsed with great slaughter and left their dead, wounded, and many prisoners besides in our hands. 153 dead rebels were buried where our Brigade alone fought and our Brigade only lost 147 men in killed and wounded (one-fifth of killed and wounded are generally killed—sometime more, sometimes less).

Our front lines are now two miles from Atlanta but it is hard telling how long they will hold out. Our left is already on and across the Atlanta & Augusta Railroad and it is reported that the Atlanta & Macon Railroad is cut. Gen. McPherson was killed a few days ago. It was a heavy loss to our [ ] for he was a fine General and has commanded the flanks of the army whenever a flank movement has been made. Sherman put a great deal of confidence in him.

I got my shirt today. It is very nice and suits me to a “T.” Many a thanks to Aunt Mary for making it. How is Aunt’s health now? and is she staying at home? I have received no writing paper yet and can’t think why they don’t come. But someone made a great bull in paying 84 cents on this bundle. A new postal law allows any package less than two pounds to go for 2 cents per ounze. Many shirts come from Massachusetts by mail for 12 to 15 cents apiece. But don’t send letters in it. Send them separate. Don’t put more than that or the post master must be a fool or a knave to charge on that.

1 Locke’s post-battle rendition of this incident corresponds favorably to other post-war accounts, one of which states: “The men of the 136th New York Regiment bore an honorable part in this battle, during which one of their number, Private Dennis Buckley, of Co. G, captured the battle flag of the 31st Mississippi, knocking down the Confederate color bearer with the butt of his musket and wrenching the colors from his grasp. While Buckley was waving the captured flag defiantly at the ranks of the enemy a bullet fired at him struck the flagstaff, glanced, and hit him in the forehead, killing him instantly. A year or more after the war closed the War Department gave a Medal of Honor to be delivered to the mother of Dennis Buckley, in recognition of his heroism at the battle of Peach Tree Creek and the capture by him of one of the enemy’s flags.”

2 The 26th Wisconsin has always laid claim that they captured the colors of the 33rd Mississippi at the Battle of Peachtree Creek. Certainly Locke’s post-battle account confirms that claim though he does not provide any specifics. It has become a matter of dispute through the years as to who actually captured that flag. [See The Capture of the 33rd Mississippi Infantry’s Colors on Civil War Talk, 14 October 2013.]

Letter 7

The following letter was written soon after Sherman’s Army had passed through Milledgeville, Georgia, on its March to the Sea. [See Week 31: The sack of Milledgeville, by Michael K. Shaffer in the Atlanta Journal Constitution.

[Early December 1864]

Dear Mother

A few days ago I sent a small box home by Express. It contained two books which I had on hand and a few other trinkets which I thought would [be] worth what the express would amount to for relief alone. The big knife I took from the State Arsenal at Milledgeville. It is a sample of what Georgia armed her soldiers with in the first of the war. There were hundreds of them in the Arsenal, but this one was of a superior kind—probably for an officer. The others were longer with wooden handle. The powder flask (U.S.) and wad pouch also came from there—plunder Uncle Sam + also the cap pouch, but the cavalry cartridge box (leather) I got at the Beverly Ford fight in Virginia. I took it from a captured rebel. The C.S.A. waist belt plate came from Resaca. The lead fuse of a shell was thrown at us from Atlanta by the Rebs.

The money and other papers came from the State House at Milledgeville. Of the money, keep a sheet of each kind for me and do with the other as you please—only give Fannie some of it. Preserve the Adjt. Gen. Report & the Governor’s Message. To fill up [the box], I put in some specimens of the trees &c. found here and a piece of Spanish moss. I never saw a more splendid sight in nature than a live oak tree hung full of that long trailing moss—the tree a dark green and the moss hanging down from six to ten feet long and proportionally thick and heavy. But the branch with buds on it I marked as Magnolia. It is a ge-pon’ icar (I have spelt it as pronounced) It is a splendid shrub and I have seen several in bloom now in the middle of January. We are having splendid weather, mild and comfortable.

But I must close. Goodbye. — Jose

[to] Mother