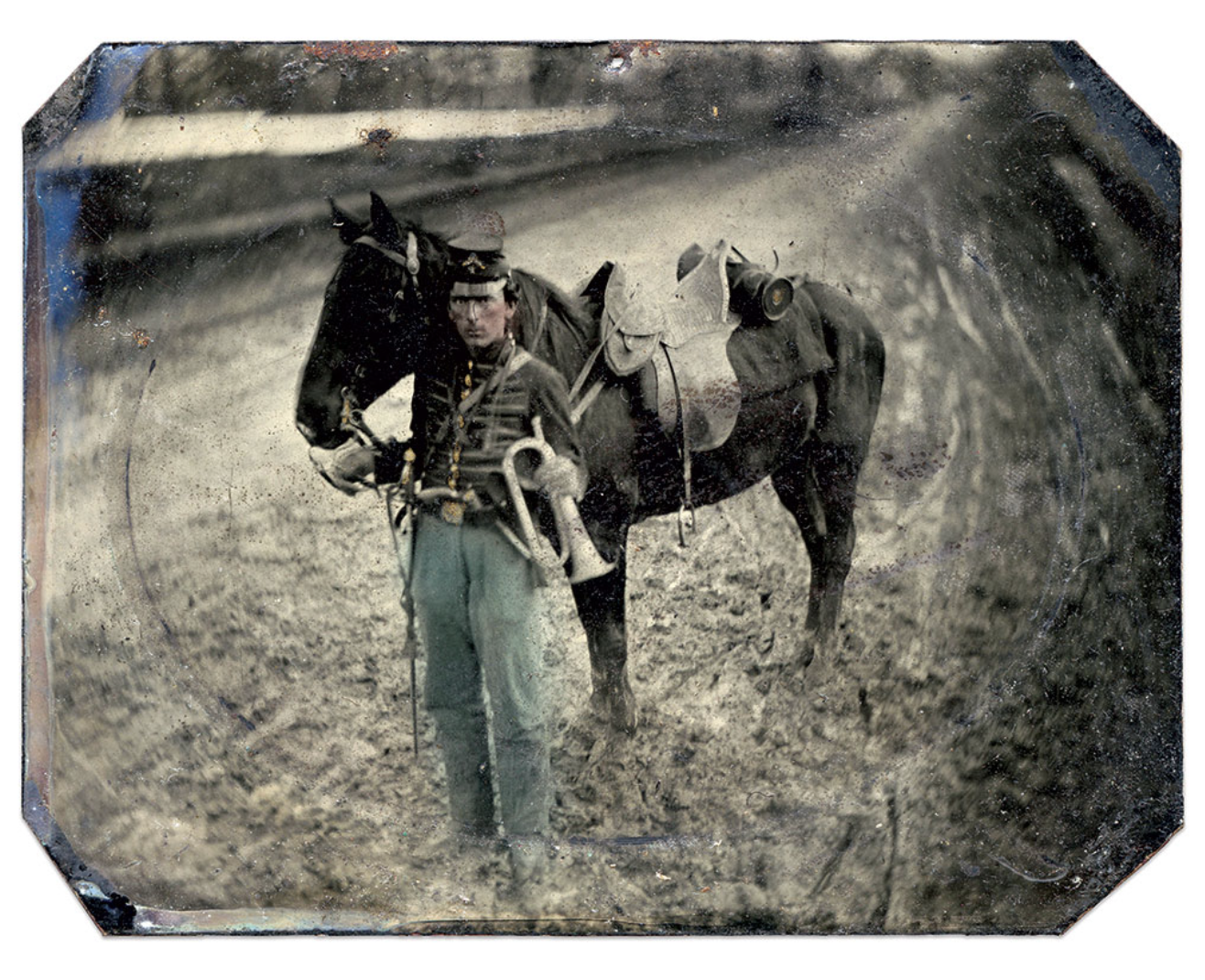

The following letter was Reuben Wheeler Coy (1843-1896), a former student of Genessee Wesleyan College, who enlisted on August 5, 1862, when he was 19 years old as a private in Co. K , 1st New York Mounted Rifles. He was appointed as company bugler and served in the regiment until June 12, 1865, when he was mustered out at Richmond, Va. After the war, he came to Michigan and settled in Elk Rapids where he taught school for one year. He then entered the employ of Dexter and Noble, as a salesman in their store. In 1870, he resigned his position, opened a general store in Helena Township and platted the village of Spencer Creek, now called Alden. A few years later, he built a gristmill at the site of the old gray building on the southeast side of Spencer Creek at Coy Street and subsequently a sawmill. Three years later he married Helen M. Thayer, the daughter of Lucius and Helen Thayer of Clam River. Helena Township was named for Coy’s mother-in-law Mrs. Thayer, the first woman pioneer in the area.

Reuben was the son of Benjamin Chambers Coy (1806-1897) and Caroline Reed (1811-1899) of Livonia, Livingston county, New York. Reuben wrote the letter to his older brother, Justus F. Coy (1840-1920) who enlisted as a sergeant in Co. G, 1st New York Dragoons, and later rose to Captain of his company. He was wounded on 11 June 1864 at Trevillian Station, Virginia. but survived and mustered out of the service in June 1865.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Camp 1st Mounted Rifles N. Y. Volunteers

Point of Rocks, Virginia

June 20th 1864

Dear brother Justus,

Where under the sun are you, I wonder. You are somewhere under the sun I suppose but that is about as far as my knowledge extends for I have not heard from or about you since the first of May. Grant’s army is here and part of Sheridan’s cavalry also dismounted. I have read about the Dragoons in the papers and suppose now that you are left on the north side of the James to look after prowling bands of rebels.

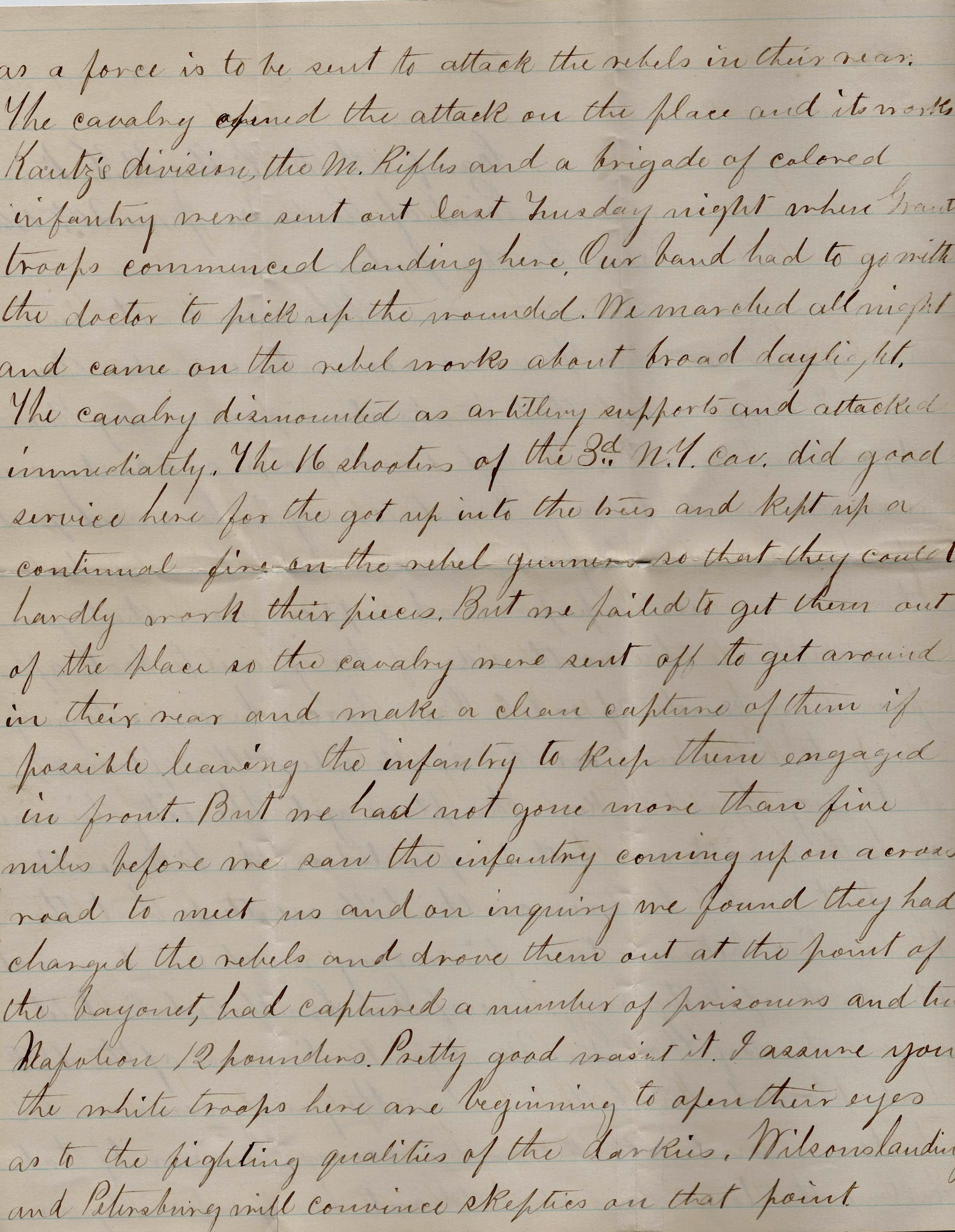

The cavalry opened the attack on the place and its works. Kautz’s division, the Mounted Rifles, and a brigade of colored infantry were sent out last Tuesday night where Grant’s troops commenced landing here. Our band had to go with the doctor to pick up the wounded. We marched all night and came on the rebel works about broad daylight. The cavalry dismounted as artillery supports and attacked immediately. The 16 shooters of the 3rd New York Cavalry did good service here for they got up into the trees and kept up a continual fire on the rebel gunners so that they could hardly work their pieces. But we failed to get them out of the place so the cavalry were sent off to get around in their rear and make a clean capture of them if possible leaving the infantry to keep them engaged in front.

Our forces here are laying siege to Petersburg on the south side of the Appomattox but they haint taken the place yet. The city lies in a hollow with our batteries planted on the hills south and the rebel batteries on the hills north so that the town lies between two fires very much as it was at the Battle of Gettysburg. One of Gen. Smith’s orderlies told me yesterday that Gen. Martindale’s division of the 18th [Army Corps] had planted their batteries where they easily commanded the town and all the bridges across the river. If that be true, the town cannot hold out long—especially as a force is to be sent to attack the rebels in their rear.

“I assure you the white troops here are beginning to open their eyes as to the fighting qualities of the darkies. Wilson’s Landing and Petersburg will convince skeptics on that point.“

— Reuben Coy, 1st New York Mounted Rifles, 20 June 1864

But we had not gone more than five miles before we saw the infantry coming upon a cross road to meet us and on inquiry, we found they had charged the rebels and drove them out at the point of the bayonet, had captured a number of prisoners, and two Napoleon 12-pounders. Pretty good, wasn’t it? I assure you the white troops here are beginning to open their eyes as to the fighting qualities of the darkies. Wilson’s Landing [see Battle of Wilson’s Wharf] and Petersburg will convince skeptics on that point.

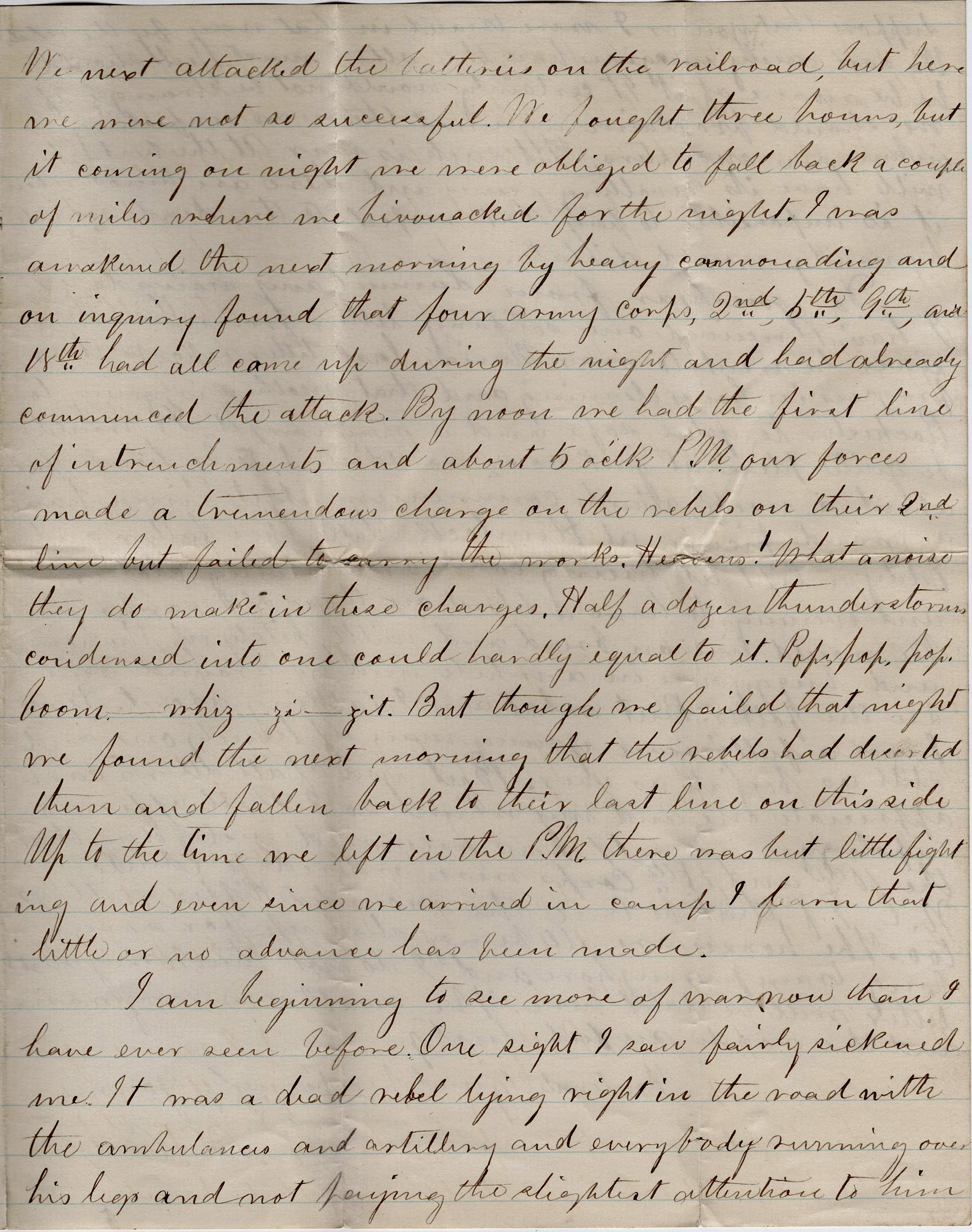

We next attacked the batteries on the railroad but here we were not so successful. We fought three hours but it coming on night, we were obliged to fall back a couple of miles where we bivouacked for the night. I was awakened the next morning by heavy cannonading and on inquiry, found that four Army Corps—2nd, 5th, 9th, and 18th—had all come up during the night and had already commenced the attack. By noon we had the first line of entrenchments and about 5 o’clock p.m. our forces made a tremendous charge on the rebels on their 2nd line but failed to carry the works. Heavens! What a noise they do make in these charges. Half a dozen thunderstorms condensed into one could hardly equal to it. Pop, pop, pop, boom—whiz—zi—zit. But though we failed that night, we found the next morning that the rebels had deserted them and fallen back to their last line on this side. Up to the time we left in the p.m., there was but little fighting and even since we arrived in camp, I learn that little or no advance has been made.

I am beginning to see more of war now than I have ever seen before. One sight I saw fairly sickened me. It was a dead rebel lying right in the road with the ambulances and artillery and everybody running over his legs and not paying the slightest attention to him. Suppose that you or I were treated in that way by the rebels. We can easily imagine how the other must feel should he be aware of it. It certainly would not be strange if we should proclaim against them as unfeeling, inhuman monsters. Yet such is war. At the best it will have its revolting scenes and there are times when it is impossible to pay that respect to the dead which humanity would dictate.

Do you hear from Samuel any nowadays? I haven’t received one solitary letter from him since he went to war. Maria’s last letter reports their progress in house cleaning and that Mother is going to Rochester to get a sofa and a new carpet. It would be quite pleasant just now, wouldn’t it, to be home for about a week, attend commencement at Lima, have a grand picnic at Hemlock Lake, give Father and Eddy a life at hoeing corn or mowing clover, and evening have a blow on those old saxhorns. We would live on bread and milk, hitch up the horse and buggy once in a while and go around and see the folks. But what am I talking about. Here I am a full grown young man of twenty-one and still as boyish as ever. But you of all others can appreciate me and my whims so I shall offer no apology.

It was rumored yesterday that the 10th and 18th Corps were ordered to Edenton, North Carolina. If that be true, the Mounted Rifles will go too. The horses are all being shod up for some long tramp anyhow and I do not think my next letter will be dated here. The weather is very warm and the roads awful dusty. Fraternally and perspiringly yours, — R. W. Coy