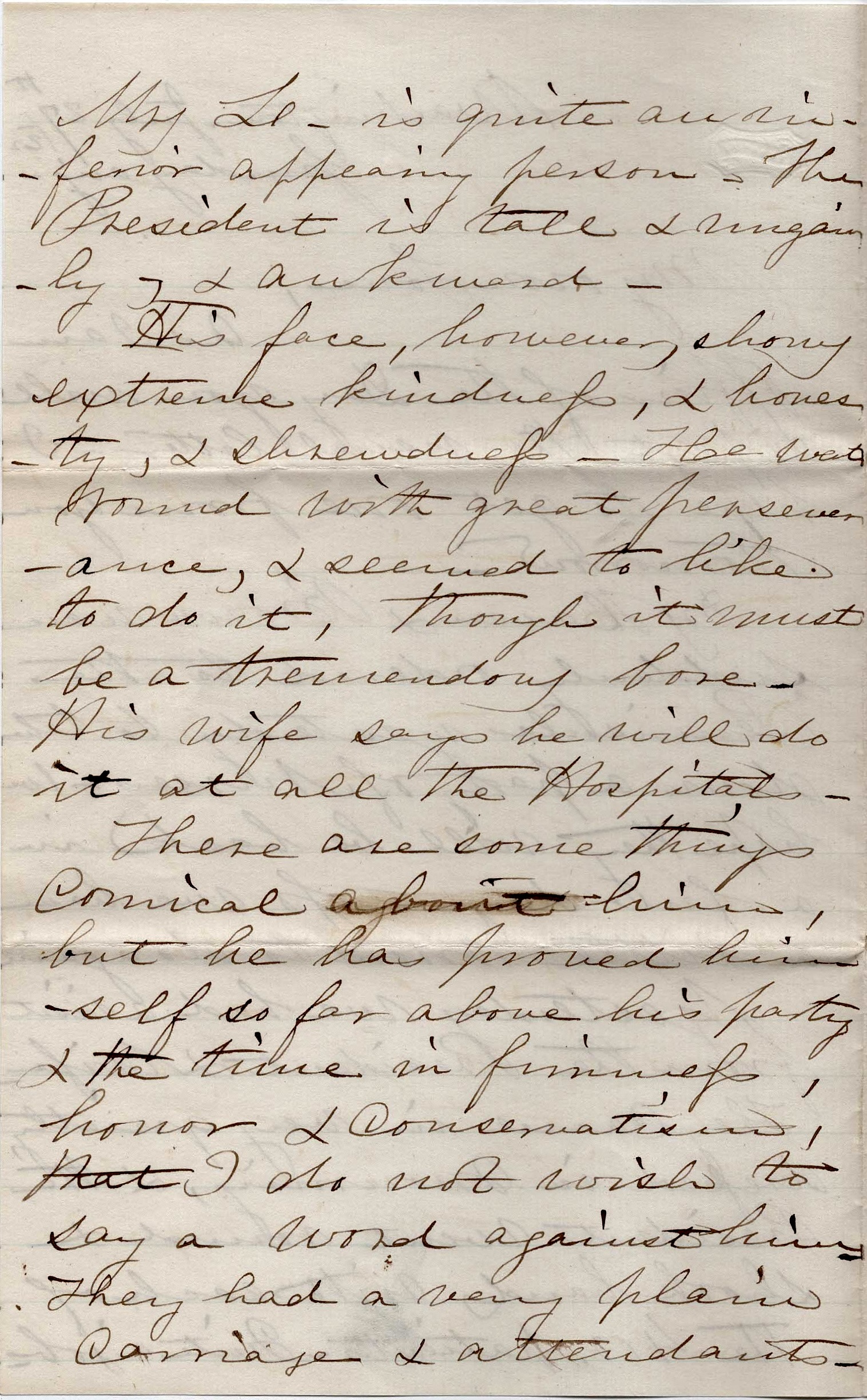

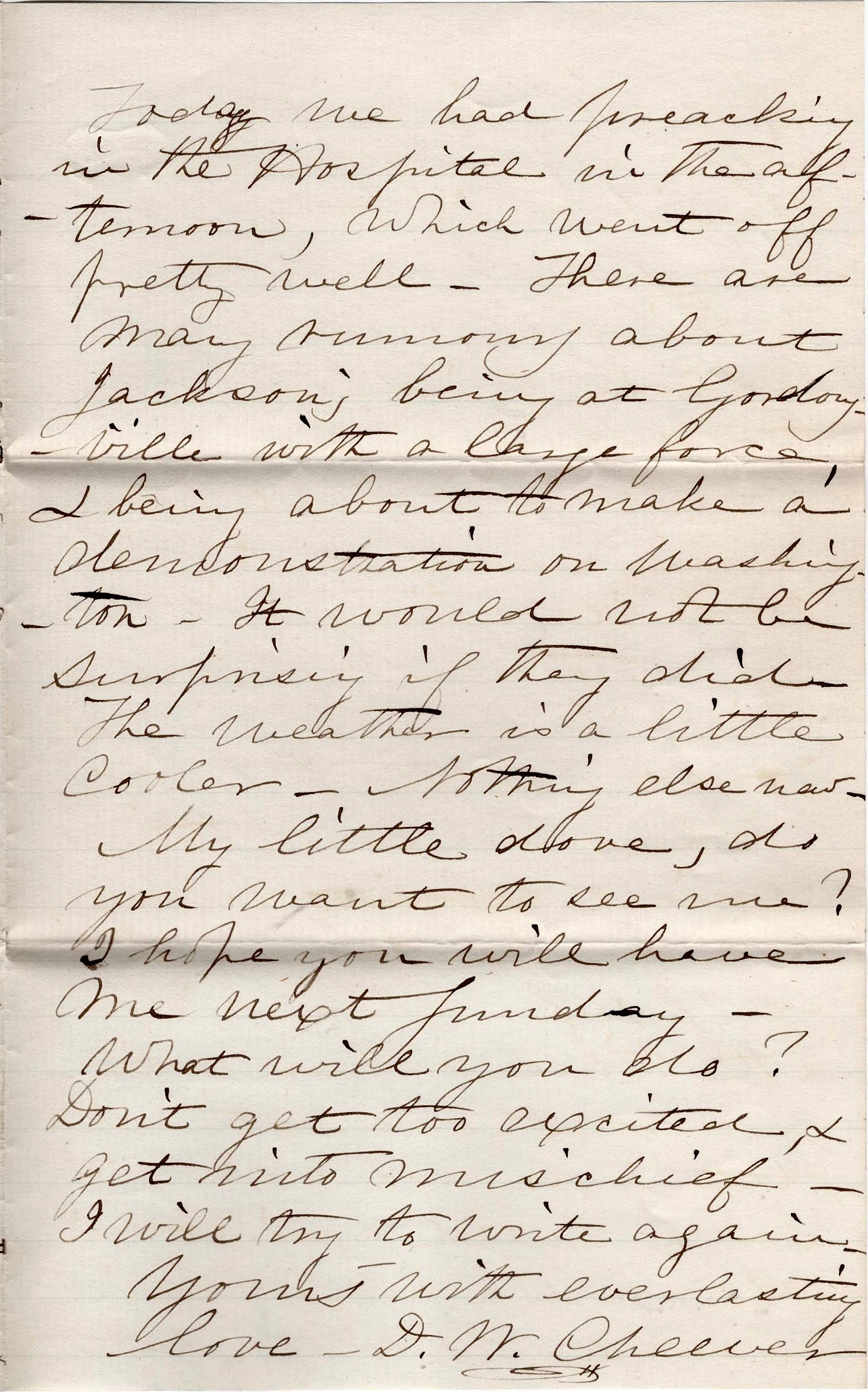

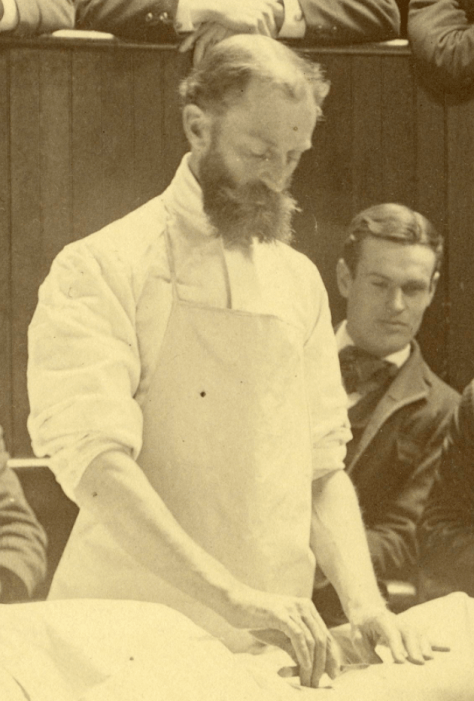

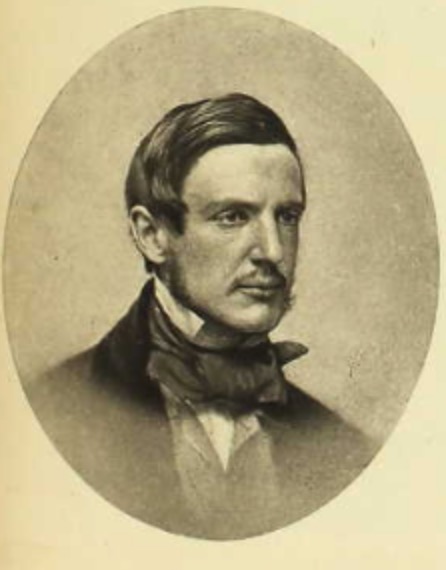

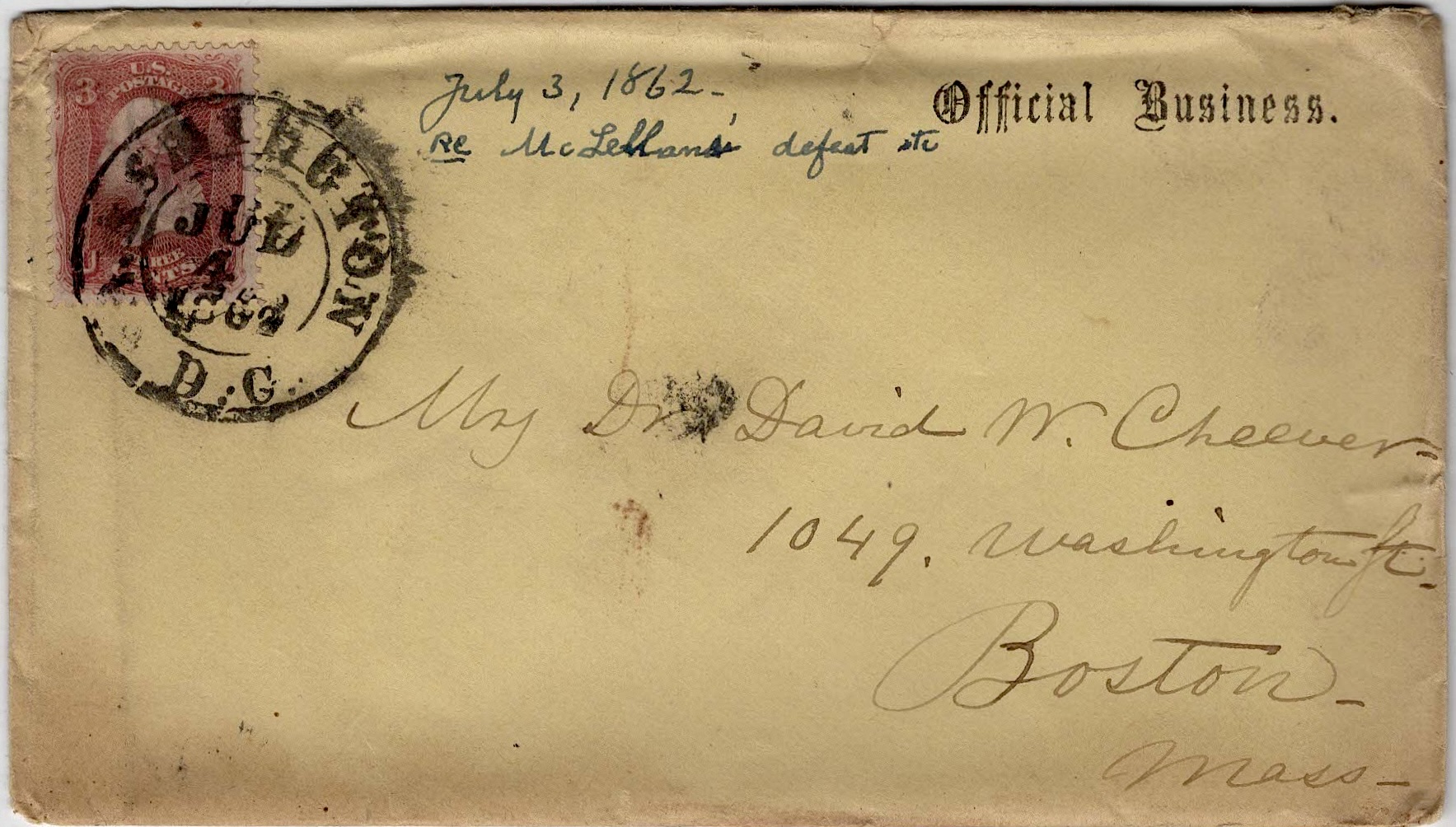

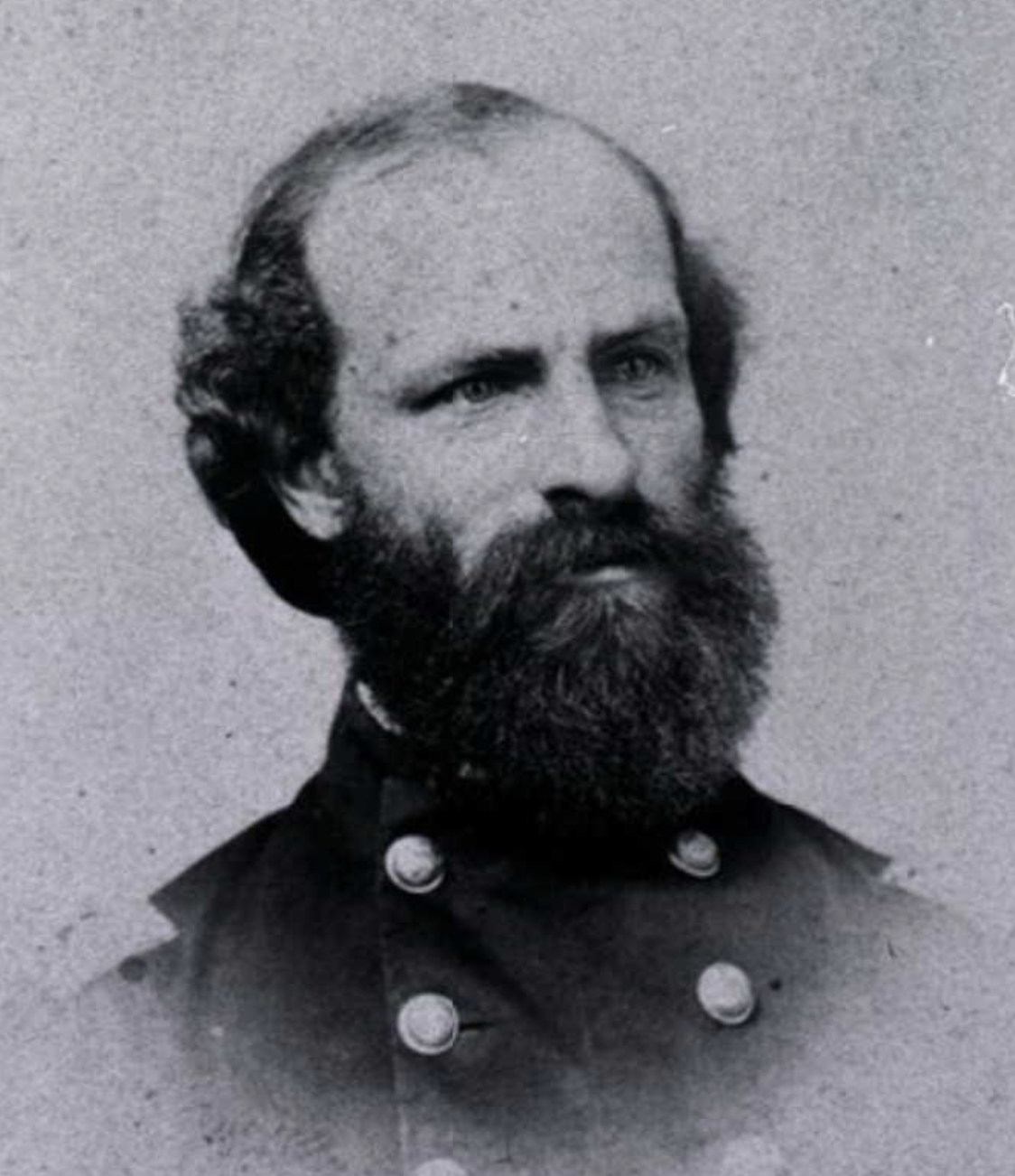

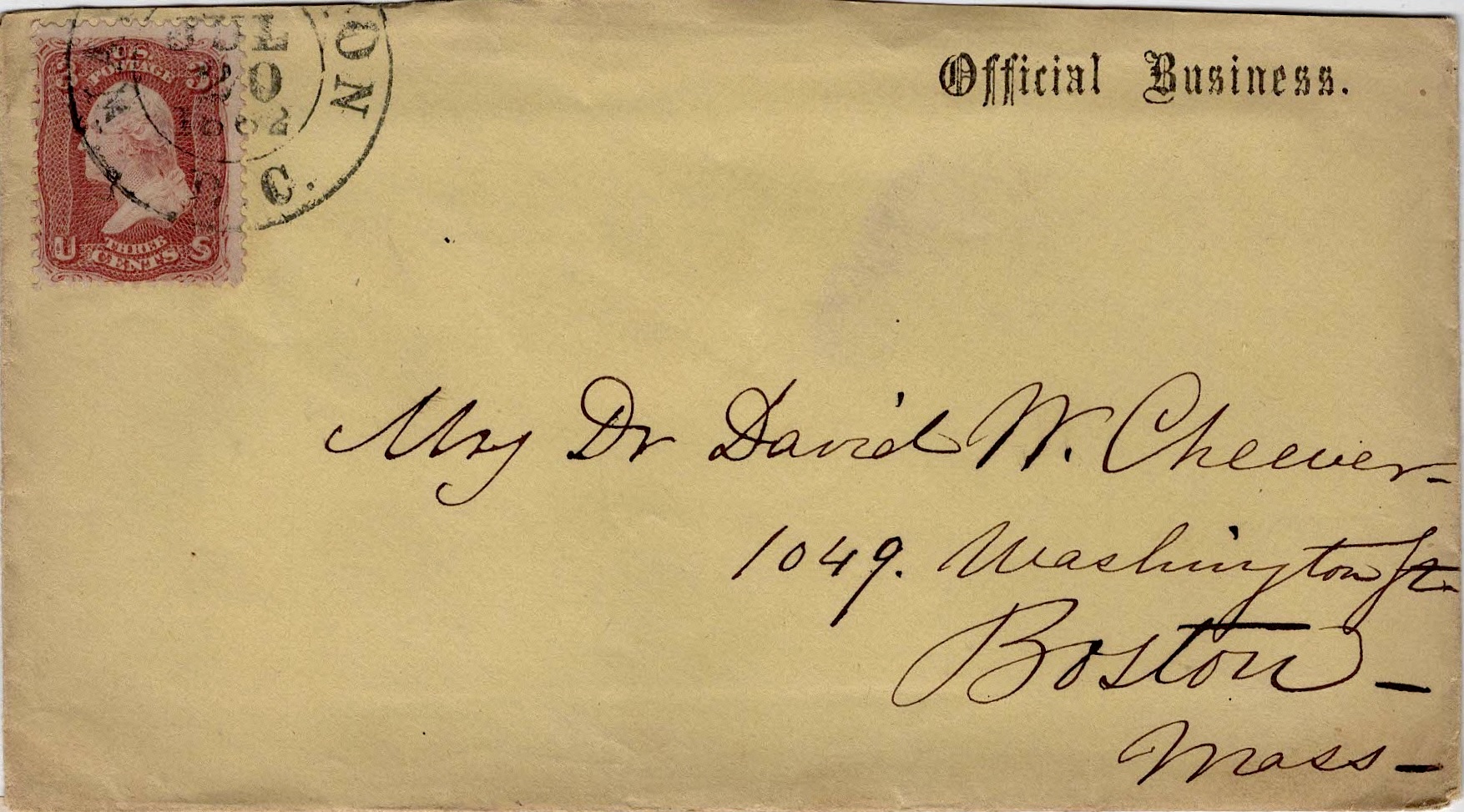

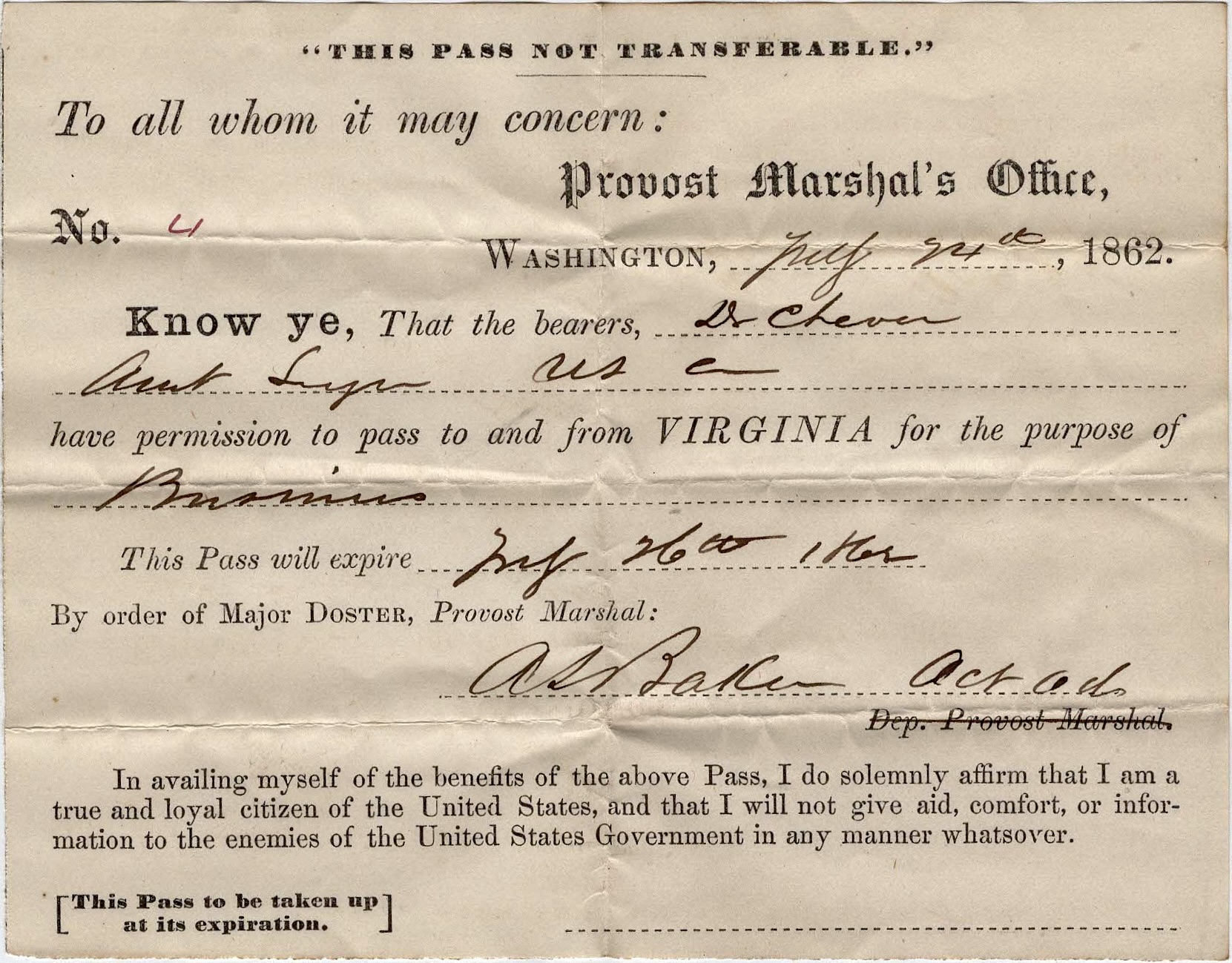

The following letters were written in 1862 by 31 year-old Dr. David Williams Cheever (1831-1915), a graduate of the Harvard Medical School where he later taught [see biographical sketch]. Cheever wrote the letters while serving as a surgeon at the Judiciary Square Hospital in Washington D. C. during the summer of 1862. This hospital was sometimes called the “Washington Infirmary.” It consisted of “commodious frame buildings” erected on the square after the burning of the first infirmary in November 1861. The new buildings were opened in April 1862.

In his letters, Cheever mentions a colleague, Dr. Frank Brown—an 1861 graduate of the Harvard Medical School. Brown mentions Cheever in a 16 June 1862 letter I transcribed in 2014 (see 1862: Francis Henry Brown to Charles Francis Wyman) which reads as follows: “Yesterday while at dinner, we received orders for one or two surgeons from our hospitals to proceed immediately to a church near the station to take charge of a large number of wounded from [Gen’l James] Shield’s Division near Winchester. So Dr. [David Williams] Cheever and I hurried our two ambulances with nurses, boys, orderlies of all kinds, instruments, soup, coffee & brandy, & went full gallop for the place. We found on arrival by some negligence our orders had been delivered too late and we had to come back. The wounded had been carried to other hospitals.”

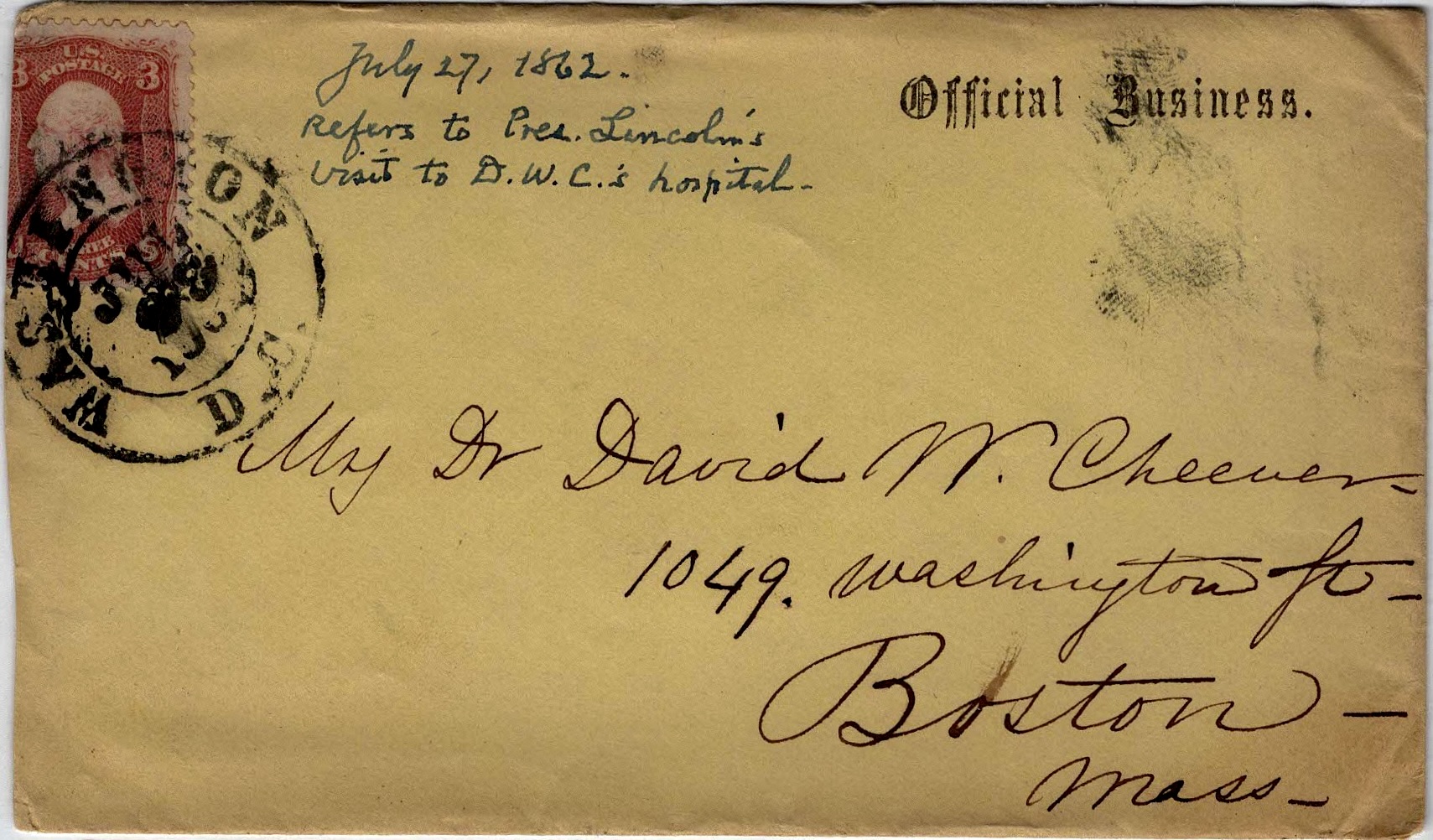

Though President Lincoln and his wife are frequently noted for their visits to various hospitals around Washington D.C. during the war, the specific account written by Cheever in his letter of 27 July 1862 is remarkable for its details on the President’s interactions with the soldiers and his impressions on both President and Mrs. Lincoln.

Dr. Cheever wrote these letters to his wife, Anna C. (Nichols) Cheever with whom he married in 1860.

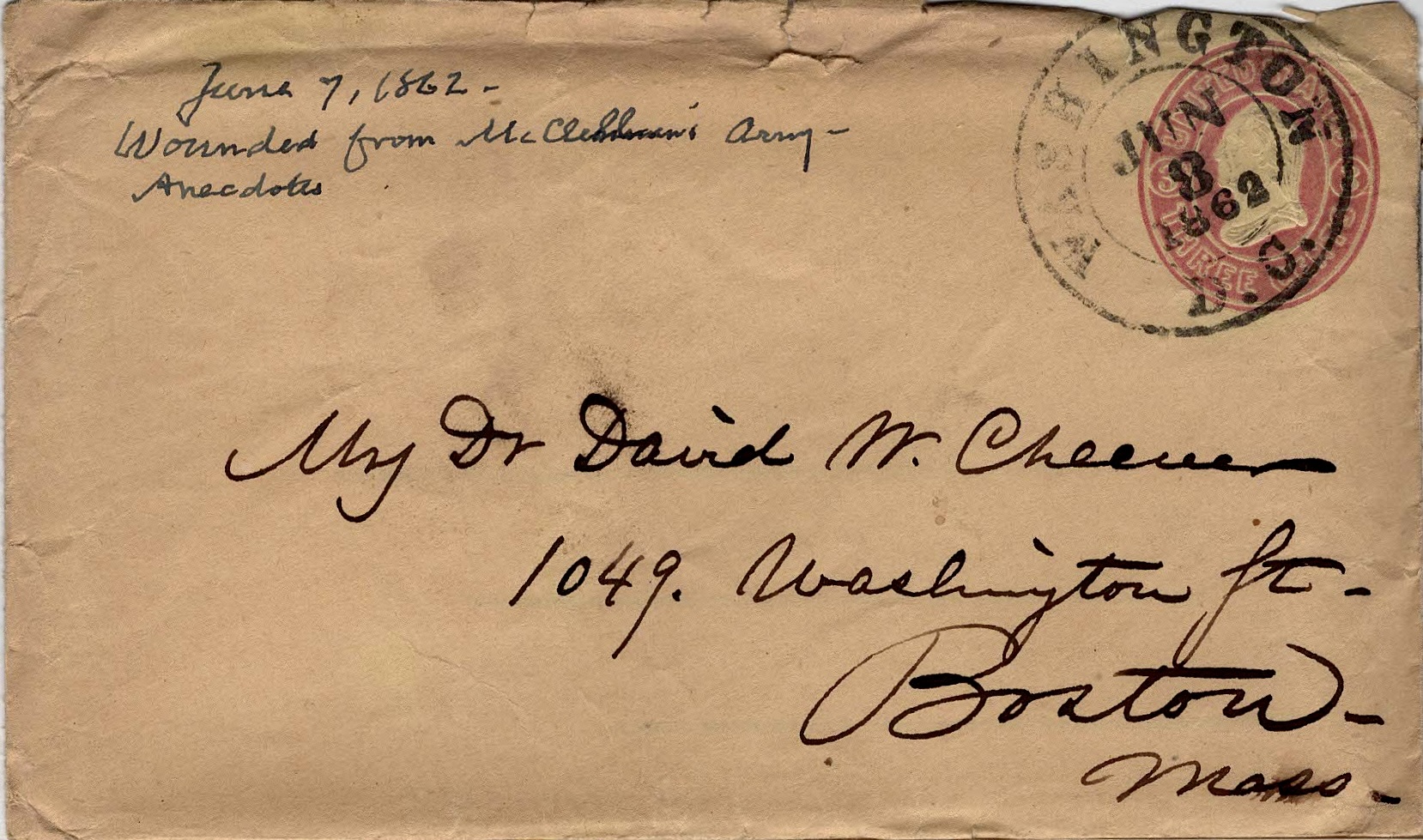

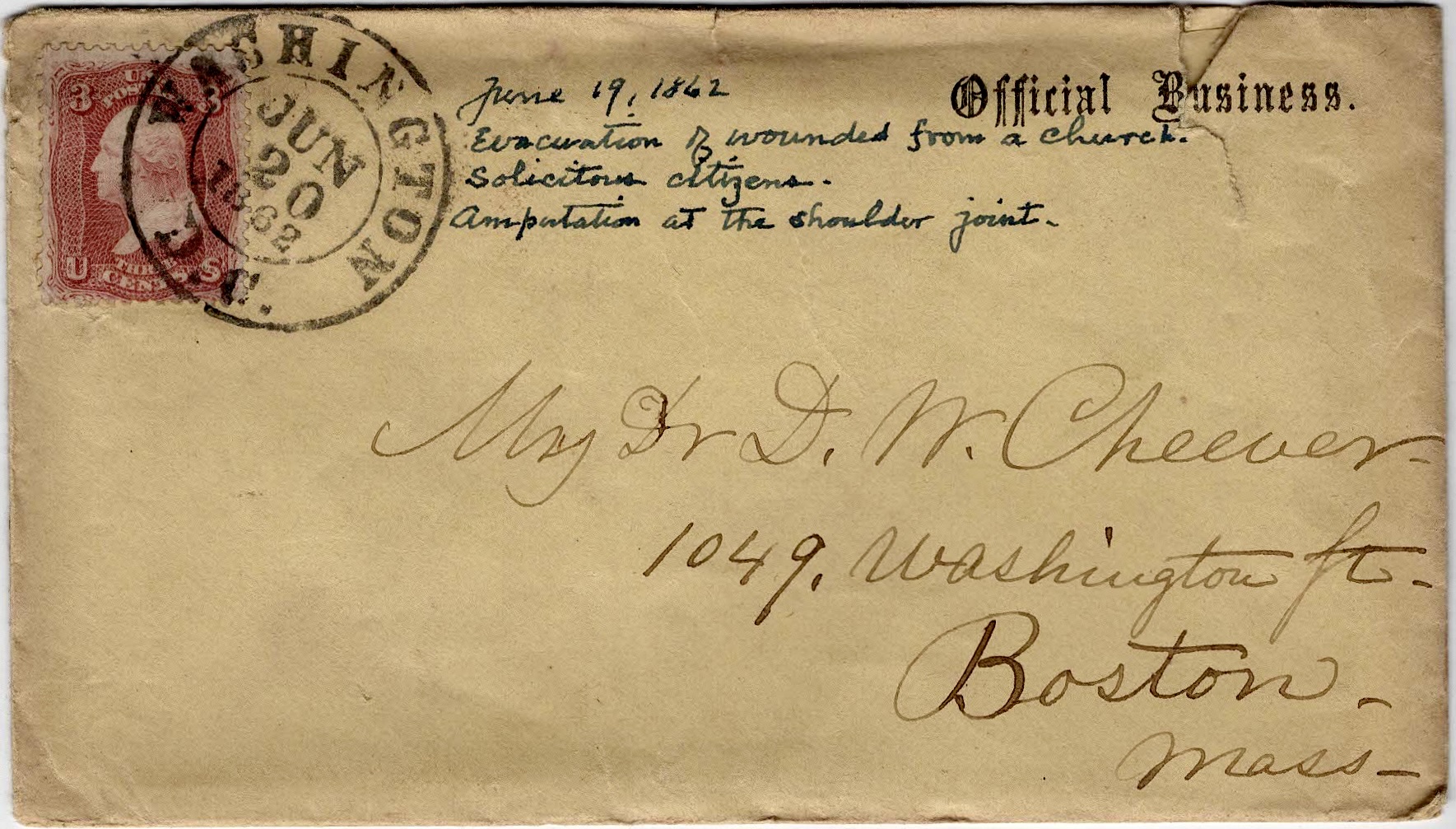

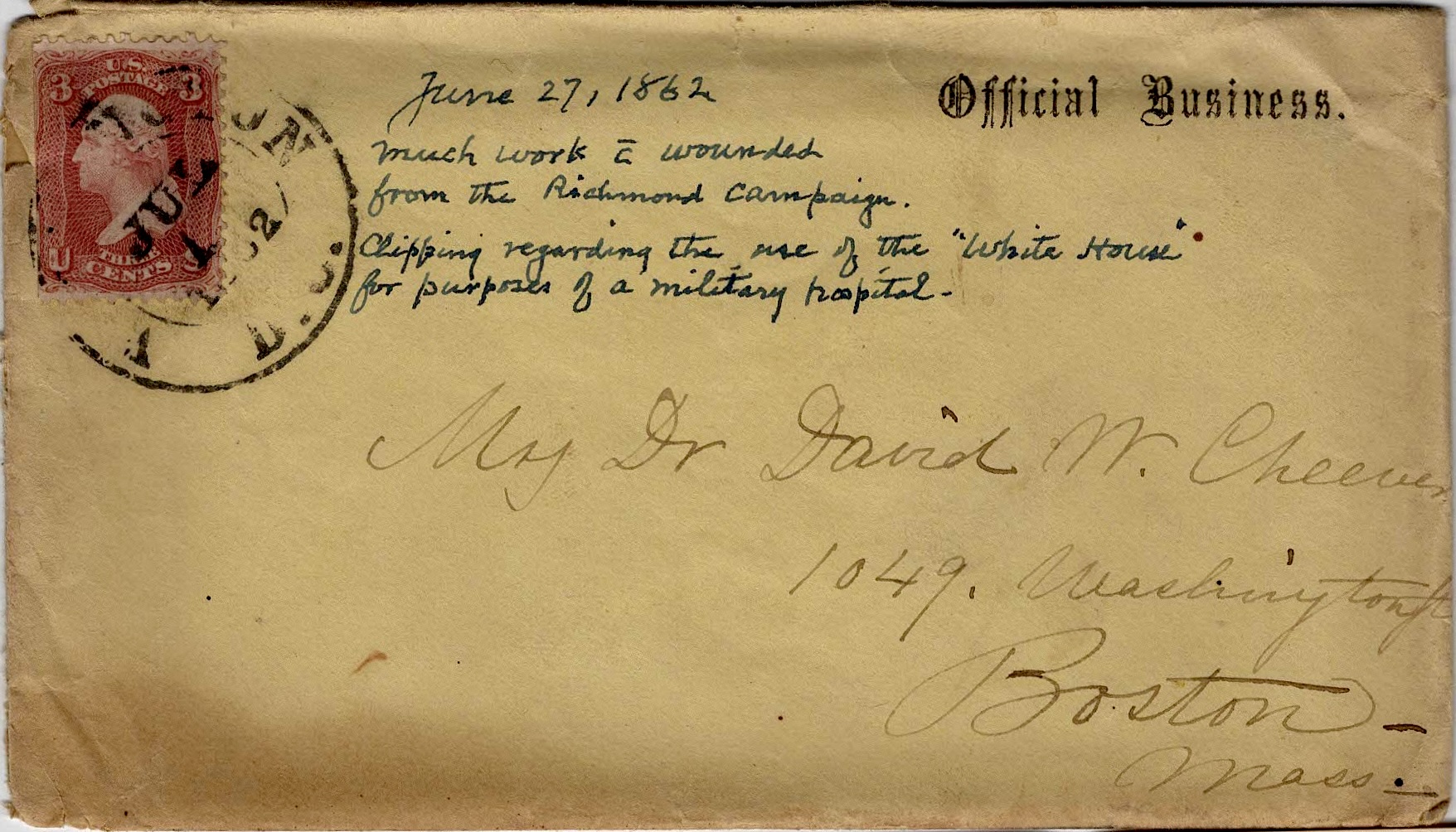

Letter 1

Washington

June 7th 1862

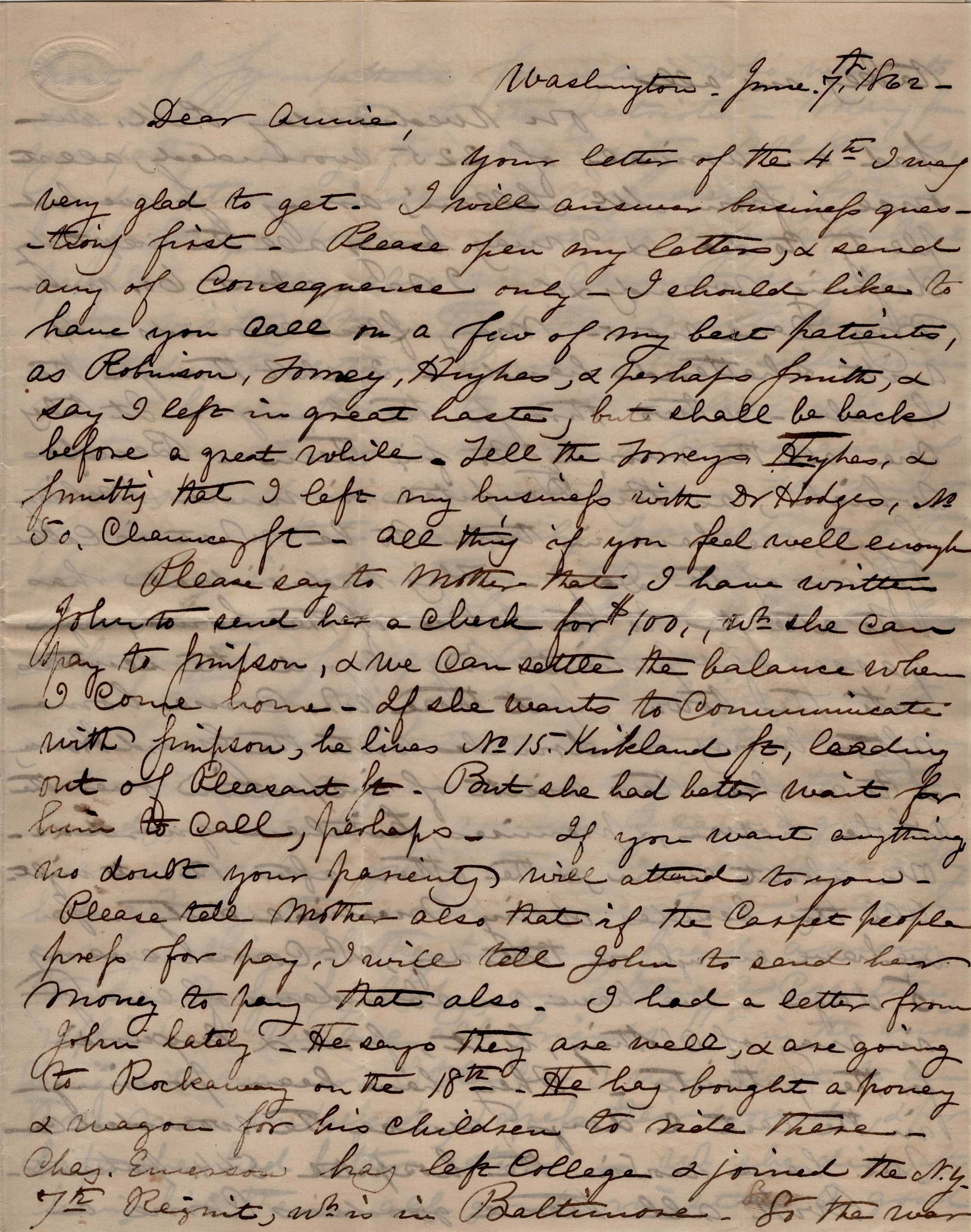

Dear Annie,

Your letter of the 4th I was very glad to get. I will answer business questions first. Please open my letters & send any of consequence only. I should like to have you call on a few of my best patients, as Robinson, Tomey, Hughes, & perhaps Smith, and say I left in great haste, but shall be back before a great while, Tell the Tomey’s, Hughes, & Smith’s that I left my business with Dr. Hodges, No. 50, Chauncey Street. All things if you feel well enough.

Please say to Mother that I have written John to send her a check for $100 which she can pay to Simpson & we can settle the balance when I come home. If she wants to communicate with Simpson, he lives No. 15 Kirkland St. leading out of Pleasant Street. But she had better wait for him to call, perhaps. If you want anything, no doubt your parents will attend to you. Please tell Mother also that if the carpet people press for pay, I will tell John to send her money to pay that also.

I had a letter from John lately. He says they are well and are going to Rockaway on the 18th. He has bought a pony and wagon for his children to ride there. Charles Emerson has left college and joined the New York 7th Regiment which is in Baltimore. So the war takes us all.

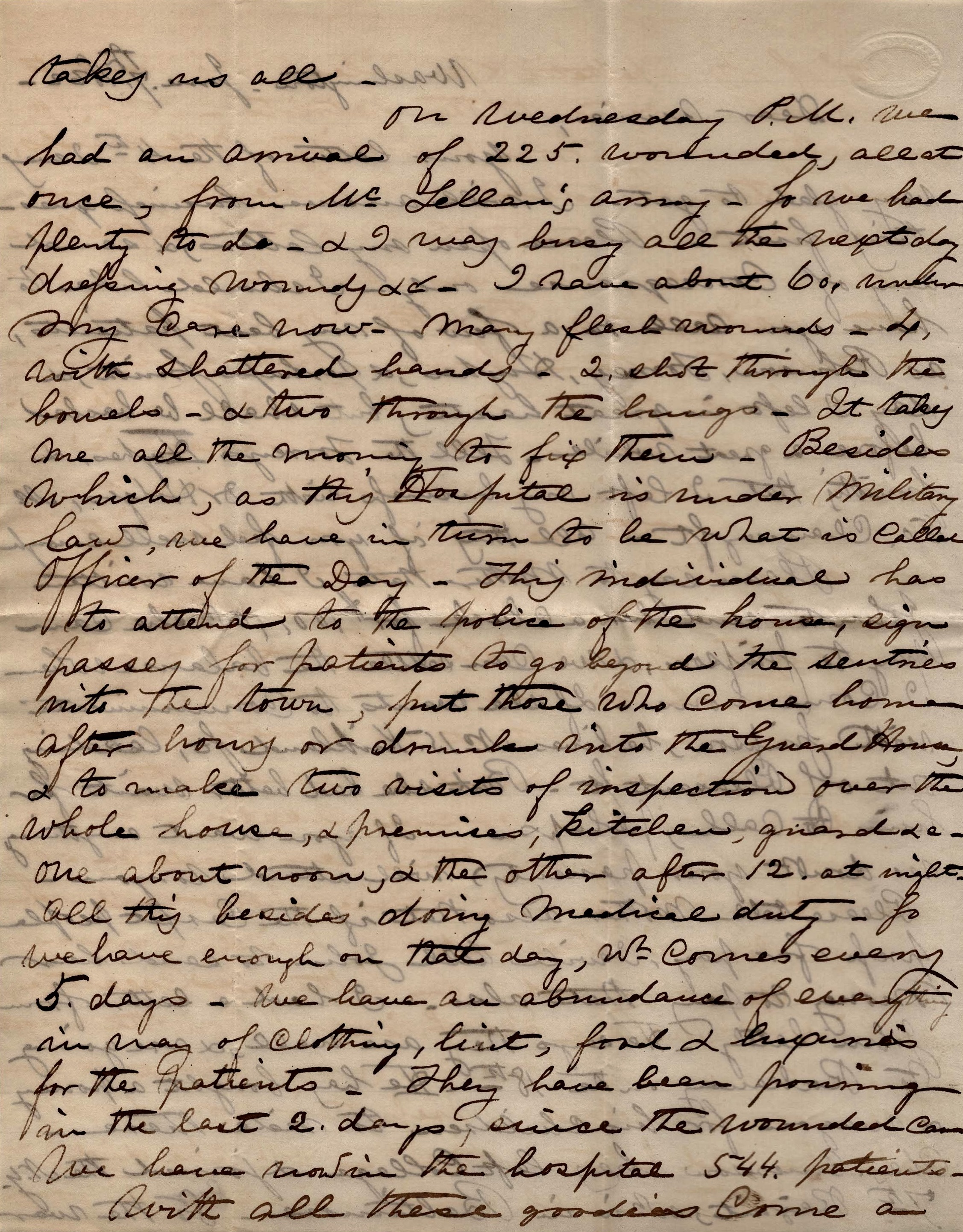

On Wednesday p.m. we had an arrival of 225 wounded, all at once, from McClellan’s army, so we had plenty to do & I was busy all the next day dressing wounds, &c. I have about 60 under my care now. Many flesh wounds—four with shattered hands, two shot through the bowels, and two through the lungs. It takes me all the morning to fix them. Besides which, as this hospital is under military law, we have in turn to be what is called Officer of the Day. This individual has to attend to the police of the house, sign passes for patients to go beyond the sentries into the town, put hose who come home after hours or drunk into the guard house, and to make two visits of inspection over the whole house & premises, kitchen, guard, &c.—one about noon and the other after 12 at night. All this besides doing medical duty. So we have enough on that day which comes ever five days.

We have an abundance of everything in way of clothing, lint, food and luxuries for the patients. They have been pouring in the last two days since the wounded came. We have now in the hospital 544 patients. With all these goodies come a host of sympathetic females who want to see and administer to the patriots—many from sympathy, many from curiosity—all kinds, good, strong, strong-minded, & impudent, from Miss Dix down. There are many excellent people. Many also who cannot understand that visitors to a hospital must be restricted to a certain hours—that sick men must have time to eat and sleep and be private sometimes, & not be a menagerie of curious & admirable wonders. The amount of flowers that are daily poured into the building is something astonishing. The wards are constantly fresh with garlands & bouquets of exquisite roses &c.

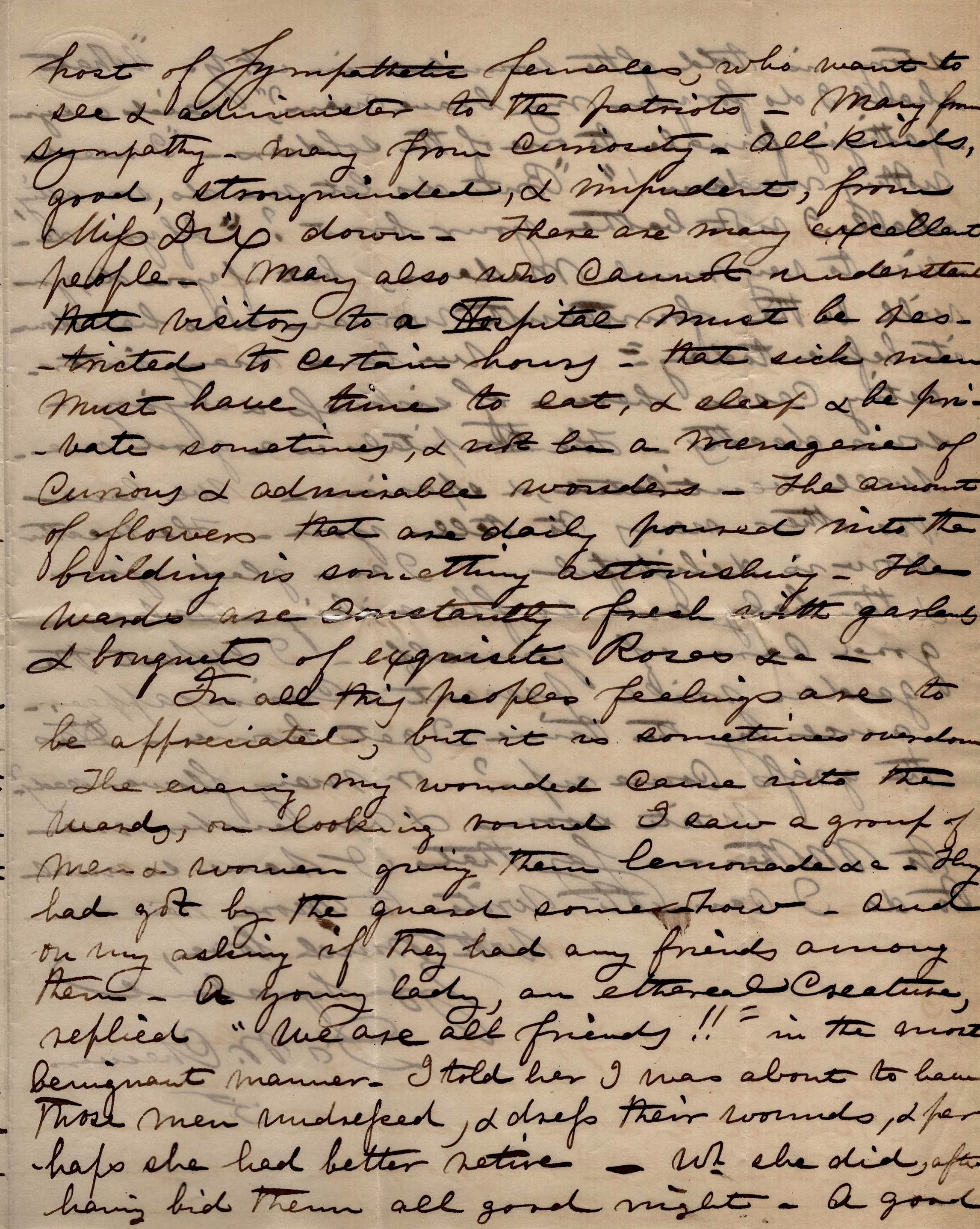

In all this, people’s feelings are to be appreciated, but it is sometimes overdone. The evening my wounded came into the ward, on looking round I saw a group of men and women giving them lemonade &c. They had got by the guard somehow, and on my asking if they had any friends among them, a young lady—an ethereal creature—replied, “We are all friends!!” in the most benignant manner. I told her I was about to have those men undressed & dress their wounds & perhaps she had better retire, which she did after having bid them all good night.

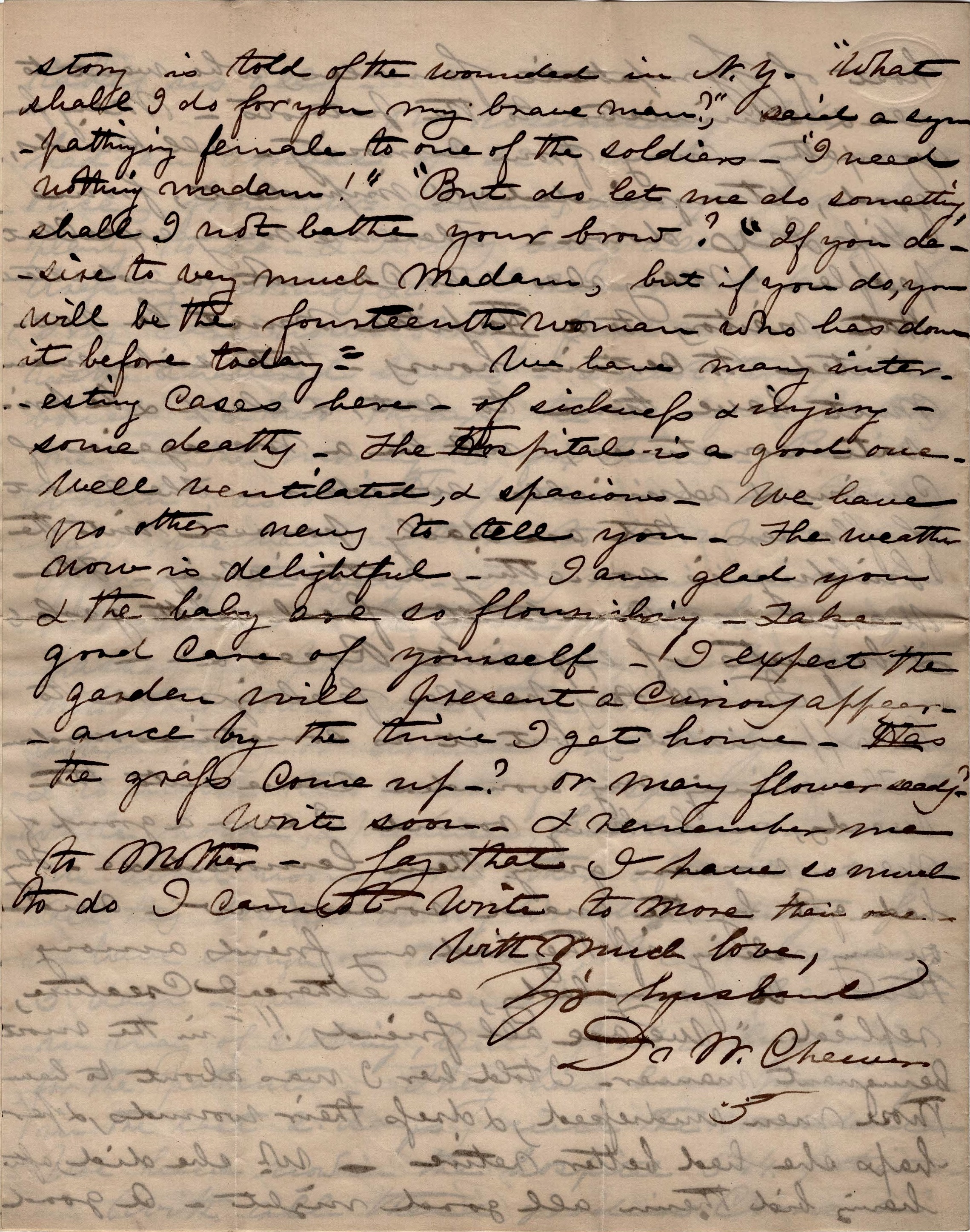

A good story is told of the wounded in New York. “What shall I do for you my brave man?” said a sympathizing female to one of the soldiers. “I need nothing, madam!” “But do let me do something. Shall I not bathe your brow?” “If you desire to very much, madam, but if you do, you will be the fourteenth woman who has done it before today.”

We have many interesting cases here of sickness and injury—some deaths. The hospital is a good one. Well ventilated and spacious. We have no other news to tell you. The weather now is delightful. I am glad you and the baby are so flourishing. Take good care of yourself. I expect the garden will present a curious appearance by the time I get home. Has the grass come up? or many flower seeds?

Write soon and remember me to Mother. Say that I have so much to do I cannot write to more than one. With much love, your husband, — D. W. Cheever

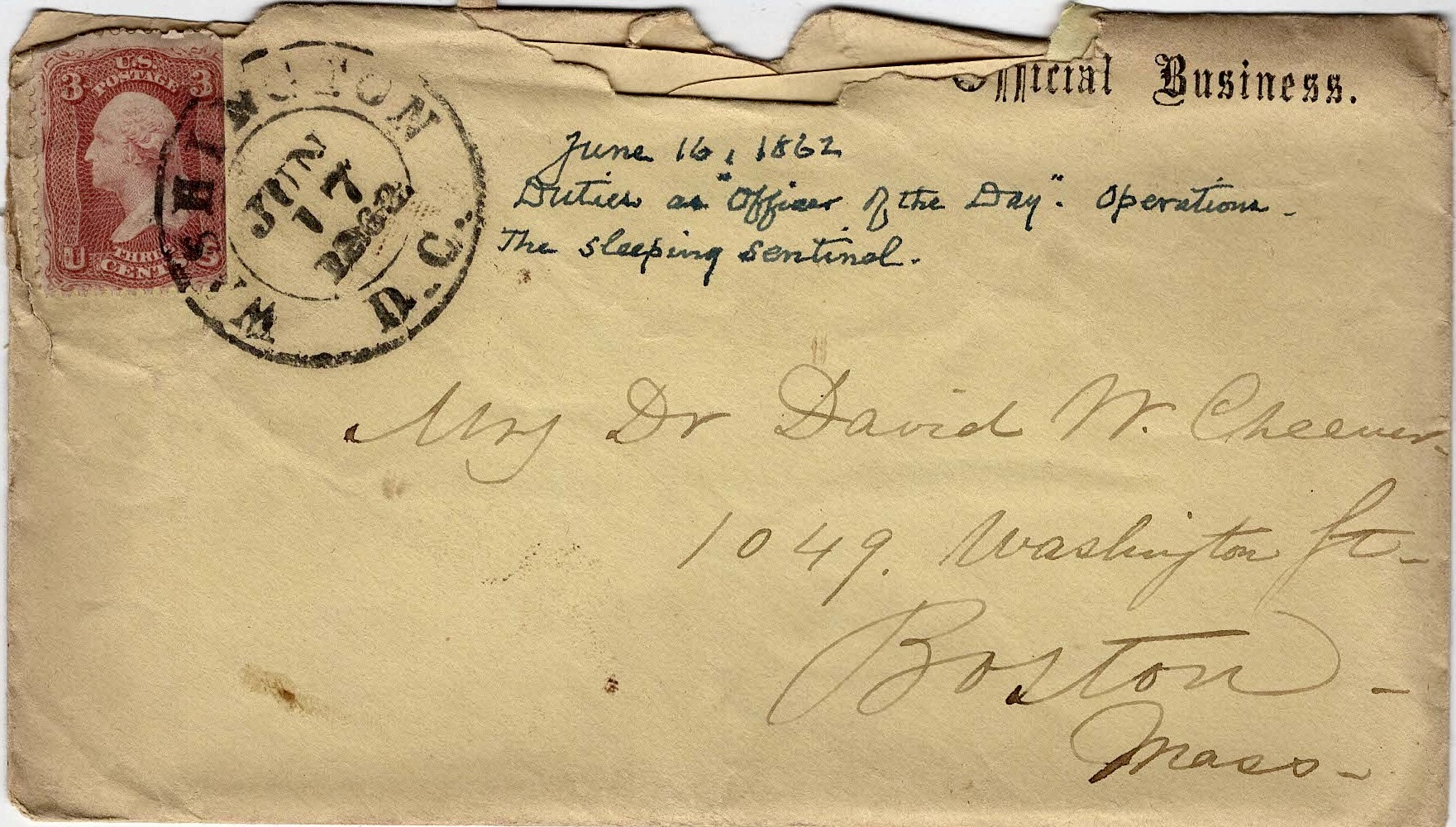

Letter 2

Washington

June 16, 1862

My dear love,

Your letters of the 11th and 13th are received. I am very much obliged to you for them both. I have delayed one day in replying, both because I have been very busy, and because I wished to give the question about my returning a mature consideration. This I have done & have come to the conclusion to stay here. Such advantages as I now have are unequaled elsewhere and I consider it worth the sacrifice of a new family to remain & improve them. I know that you are well willing to endure my absence, and as long as things go on well with you and remain advantageous here, I shall stay up to a certain time. You may, therefore, say to the gentleman that I feel it my duty to stay here just now, and cannot limit myself to return on the 1st of July, though it is not improbable that I may be back early in that month. I am very sorry & have thought a good deal of it, but it is decided now. Don’t tell Mother.

The government is making vast preparations for wounded from the expected battle of Richmond. Yet is may not come. If things become uninteresting, I may be back in two or three weeks after all. I shall not stay after the 1st of August.

On Saturday, you will be glad to learn I did my first operation. It was tying the carotid artery which is ranked among the capital or more important operations, as those are called, who success or failure involves life. I got along very well for a first time and the result promises to be successful. The case was that is a man shot through the neck and face in whom bleeding came on & could be checked in no other way. Two days before, Dr. Page tied the axillary & yesterday one of the other gentlemen amputated and arm, all for secondary hemorrhage., which comes on sometimes when the wound begins to slough.

We work hard. Fortunately a cool day has made us all feel better today. It was very hot Saturday and Saturday evening. To give you some idea of how we are kept moving, I will give you my experience from Friday night to Sunday night.

Friday night at 12, I was called to check the bleeding of this man which I did for the time. Saturday I was called by my boy at 6.30 as I have done every morning, & in order to get through my work, I make my medical visit to a medical ward before breakfast, and my surgical dressing visit in the forenoon. While at breakfast I was called again to my bleeding friend, when we tied the carotid. Then I had to make my surgical visit and dressing to 40, which with the amount of suppuration & heat going on is pretty laborious. I was Officer of the Day also and had to sign papers and all passes for the men who wanted to go out, visit the whole house, and inspect every scullery, ward, water closet & settle rows with the cooks, put the drunks &c. in the guard house, write up a hospital record of my cases, make an evening visit to my wards & wind up the day by making the grand rounds through every room, all round outside, to the guard, &c. after 12 at night.

It was a hot, but moonlight night, & going along to one place, I found the sentinel asleep & succeeded in taking his musket away unperceived & carried it off which is regarded as a great feat. I had another sentinel posted & the sleeper locked up & then went to bed. I was very sorry for the poor devil, but it was my duty to do it. He will be punished somehow. Our guard is growing slack and we are going to have a new one.

Sunday morning at 6.30 again, [worked] hard until near 12 at noon when the weekly General Inspection come, and all the officers go round together, following the head one and inspect and poke out corners and behind beds and blow up and find all the fault necessary. The hospital looks nice Sunday, I assure you, and indeed every day. It is scrubbed and mopped daily. The only difficulty is in getting clothes enough & washed fast enough to change 500 men often enough as many are wounded, &c. The way we use up bandages and supplies would astonish you. 500 loaves of bread, a keg of butter, and a barrel or 30 dozen of eggs every day, and other things in proportion. We have an abundance.

Sunday I was late at dinner because I was called off to do something in the ward. At dinner came an order to send a medical officer with nurses &c., to dress 300 wounded in a church, just arrived. I was sent with Dr. Brown as assistant, but on getting there found only five who had not been removed to other hospitals. Those five I took here and had three in my ward to attend to that evening. Then I went to bed.

Now I am going out for a little walk—first time for two days. I am very well. Love to mother. Yours affectionately, — D. W. C.

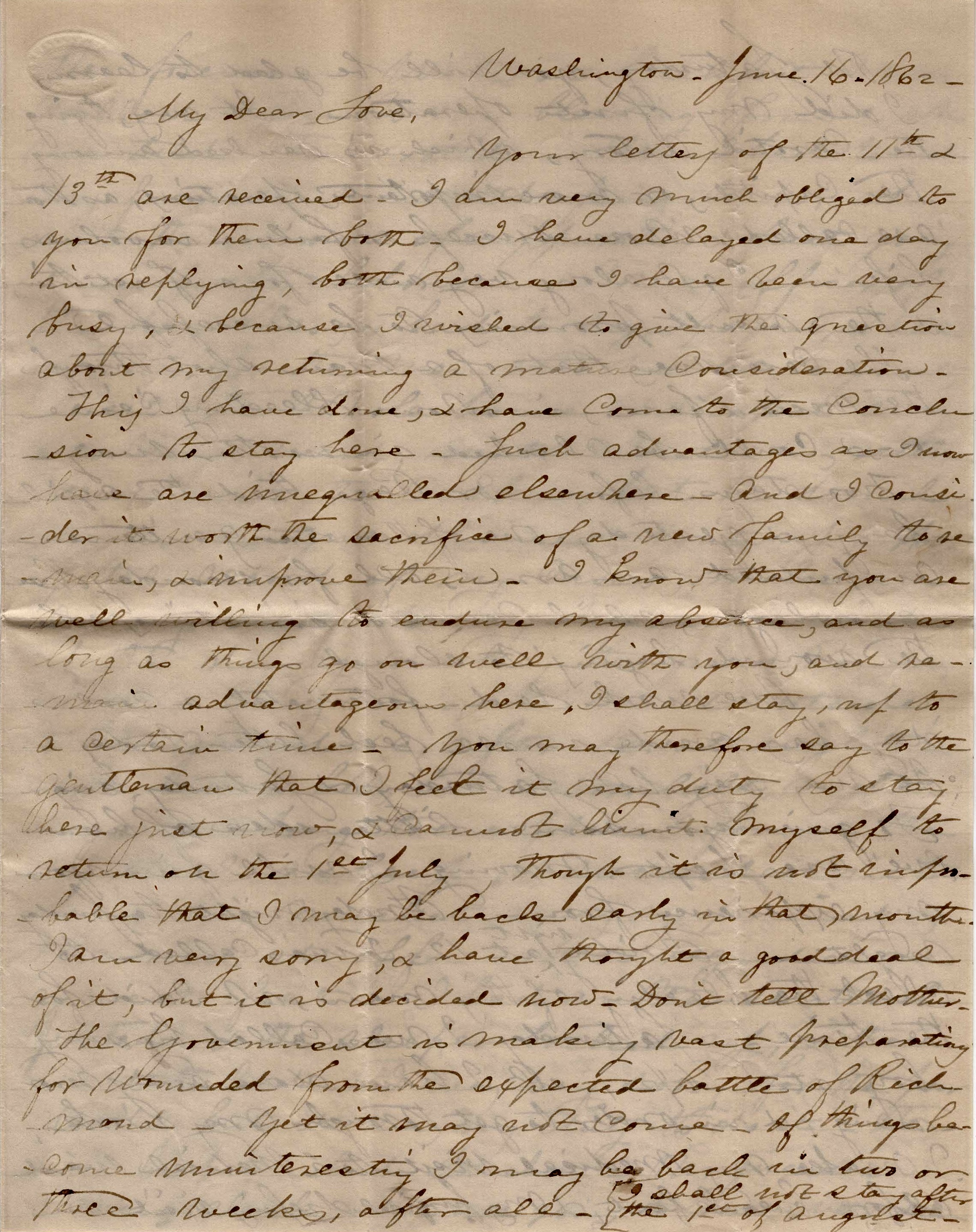

Letter 3

Washington

June 19, 1862

My dear little wife,

Here we are again, “Officer of the Day” and it is so hard to keep awake until 12 when one is tired that I am going to try the expedient of writing to you. Your welcome letter with the photography came duly to hand. I think one very good and have it pinned up over my table in my chamber. I am very glad to have even this memento of you to look at. I assure you, it is very pleasant to see when one is tired. It makes me feel very easy that you take my absence so bravely & that you are really getting along so smoothly. I trust you will continue to do so while I stay here.

I had a very pleasant letter from your brother Richard offering me any services in his power. I have answered it and also written to Demy [?] about the class supper. I don’t know of any other business that needs attending to now. Please keep me informed of how much I lose in calls, &c. and do not economize but make yourself comfortable.

I was going to tell you in my last of my experience in going to a church after wounded. We received orders to send an efficient medical officer at once with nurses, dressings, &c. to the church to take care of wounded. Dr. Page sent me with Dr. Brown as assistant, and three nurses, surgical fixings, a pail of soup, and one of coffee, &c. in an ambulance. As I have already told you, we found all had been removed but five, but we had a very ludicrous time removing them. We found a crowd extending out into the middle of the street composed mainly of ladies. Two of the patients were very sick. One laid out in front of the altar, one sitting up, and the next laid out on boards & mattresses laid over the tops of the pews. The persistence and wrath of that crowd against their being moved anywhere were astonishing. They wanted them kept there and to stay there & nurse them. All sorts of messes were around, including a huge saucepan with about a gallon of gruel. Wine and brandy were being poured into the sick in great profusion and the soldier who was sitting up with a ball through his arm began to feel so set up that he said he guessed he was well off where he was, and he would stay there.

I had two ambulances, stretchers, and a guard of six men with corporal. Those best off I put in the ambulance and had the two sickest carried up all the way by hand on the stretchers by the guard. The ladies besought me to leave them there for them to nurse all night, but finally yielded to my obedience to my orders, which told me to take all there were left to the hospital. All sorts of luxuries were forced upon the sick ones. Someone shoved a bed pan into our ambulance just as it started and one old lady tried to force upon me a bottle of lemon syrup with a rag stopper. However, off they went at last. I had to stay to see if any more were coming & detailed Dr. Brown to go up with the men on stretchers. Poor Brown! he had a sweet procession of citizens up through the streets of a Sunday afternoon following the cortege.

I stayed there two mortal hours & I answered about 500 questions in that time. There is no doubt these people were very kind & the soldiers have been shamefully neglected somehow. They arrived the evening before by railroad from Shields’ Division & no news of their coming being known, had to stay in the cars all night, or go into the church. All were fed by the citizens and many taken into private houses for the night. You have seen perhaps that the surgeon in charge of them has been dismissed from the service for alleged neglect. It is hard to say whose fault is was.

Congratulate me that I did a grand operation yesterday of amputation at the shoulder joint. It came out well & is thought one of the bigger operations—much more than a common amputation of arm or leg. I had the whole surgical staff to assist and a big fuss generally. There was no alternative for the man but amputation or death—gangrene having extended to within 6 inches of the shoulder.

Today Dr. Brown had a hemorrhage & may tie a big artery soon. So we go. We have received orders to hold all our convalescents & lighter cases ready to send away at any time to make room for others.

Love to all. Yours, — D. W. C.

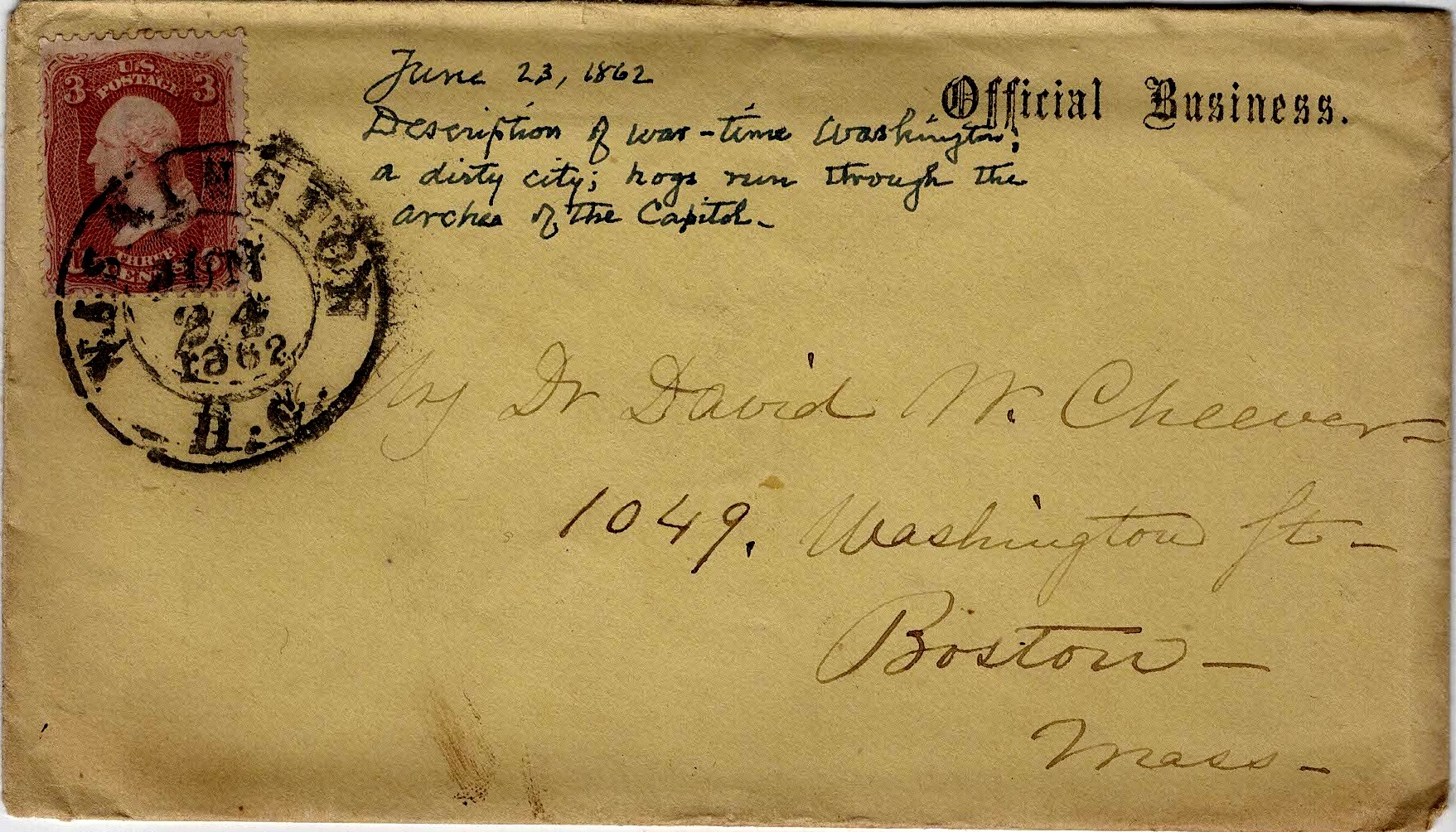

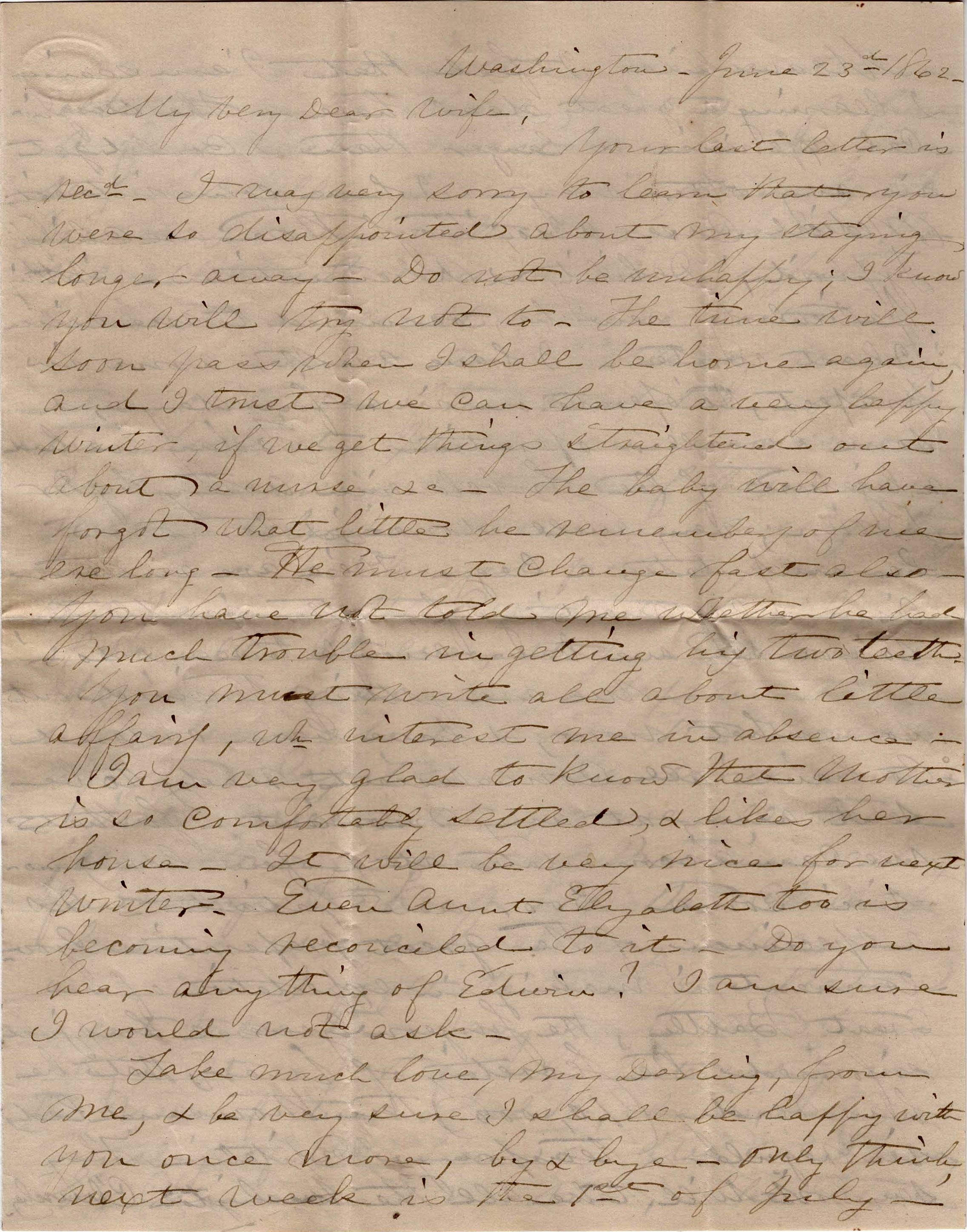

Letter 4

Washington

June 23, 1862

My very dear wife,

Your last letter is received. I was very sorry to learn that you were so disappointed about my staying longer away. Do not be unhappy; I know you will try not to. The time will soon pass when I shall be home again, and I trust we can have a very happy winter if we get things straightened out about a nurse, &c. The baby will have forgot what little he remembers of me ere long. He must change fast also. You have not told me whether he had much trouble in getting his two teeth. You must write all about little affairs which interest me in absence. I am very glad to know that Mother is so comfortably settled & likes her house. It will be very nice for next winter. Even Aunt Elizabeth too is becoming reconciled to it. Do you hear anything of Edwin? I am sure I would not ask.

Take much love, my darling, from me and be very sure I shall be happy with you once more, by and bye. Only think, next week is the 1st of July.

Meanwhile I feel that I am seeing and learning a great deal here. The surgical experience is larger than I could get in any other way. I have some interesting medical cases also, though those are chiefly typhoid, debility, & rheumatism. Nothing particularly new has occurred to me since I last wrote. I have another arm in prospect to operate on in a few days, and some smaller operations. Today we had a ligature of the subclavian artery by Dr. Brown, very well done. And tomorrow he amputates a leg. There are another arm and leg waiting for other gentlemen so you see we have enough to see and do.

We are getting thinned out somewhat now and have been ordered to have all convalescents ready to be sent away at any moment so that we can accommodate at a few hours notice some 300 new patients. As a specimen of the great preparations government is making in expectation of a great battle, the Surgeon General has just informed the Secretary of War that he has ready then thousand of beds in regular & temporary hospitals. They say government will take all the Washington churches.

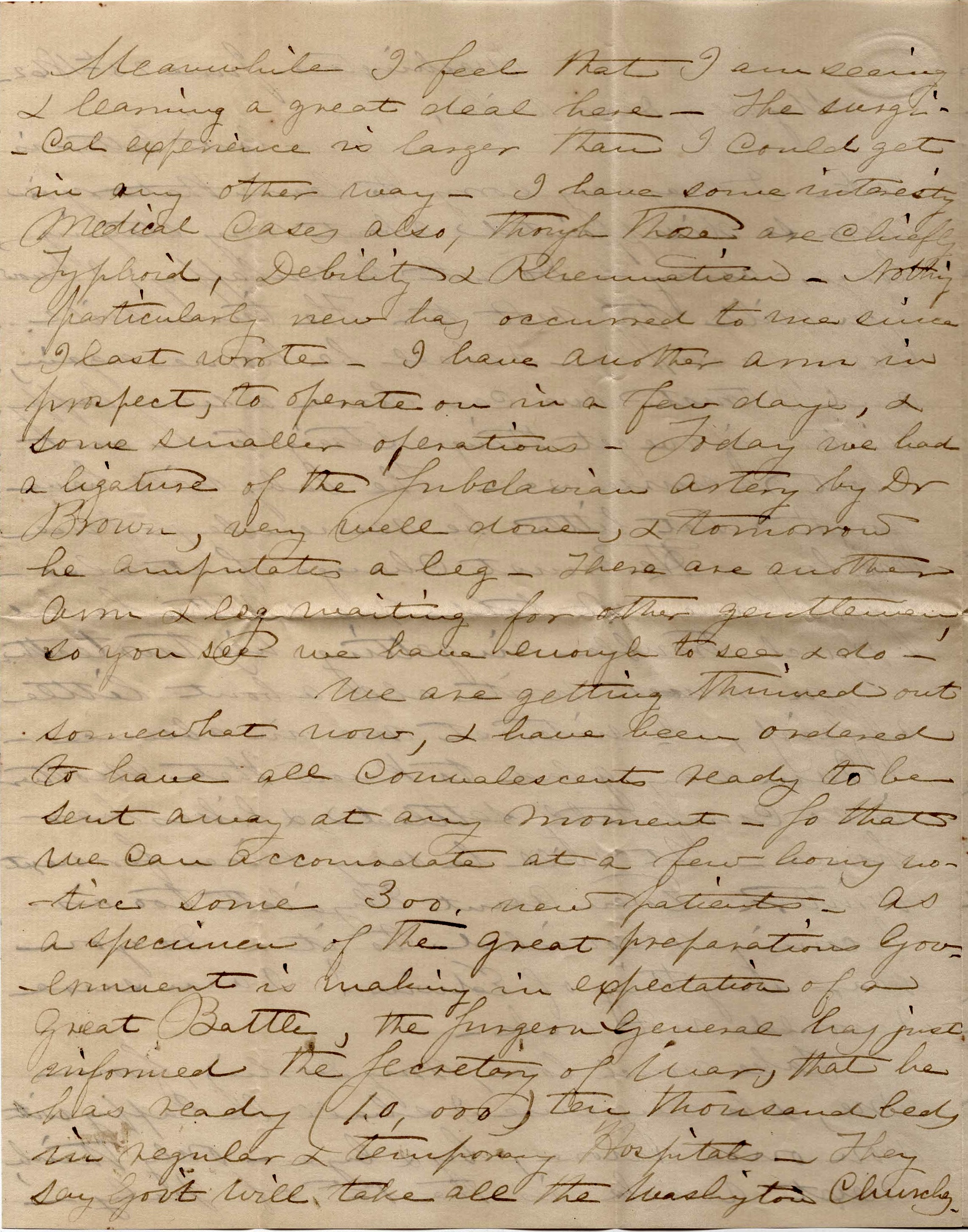

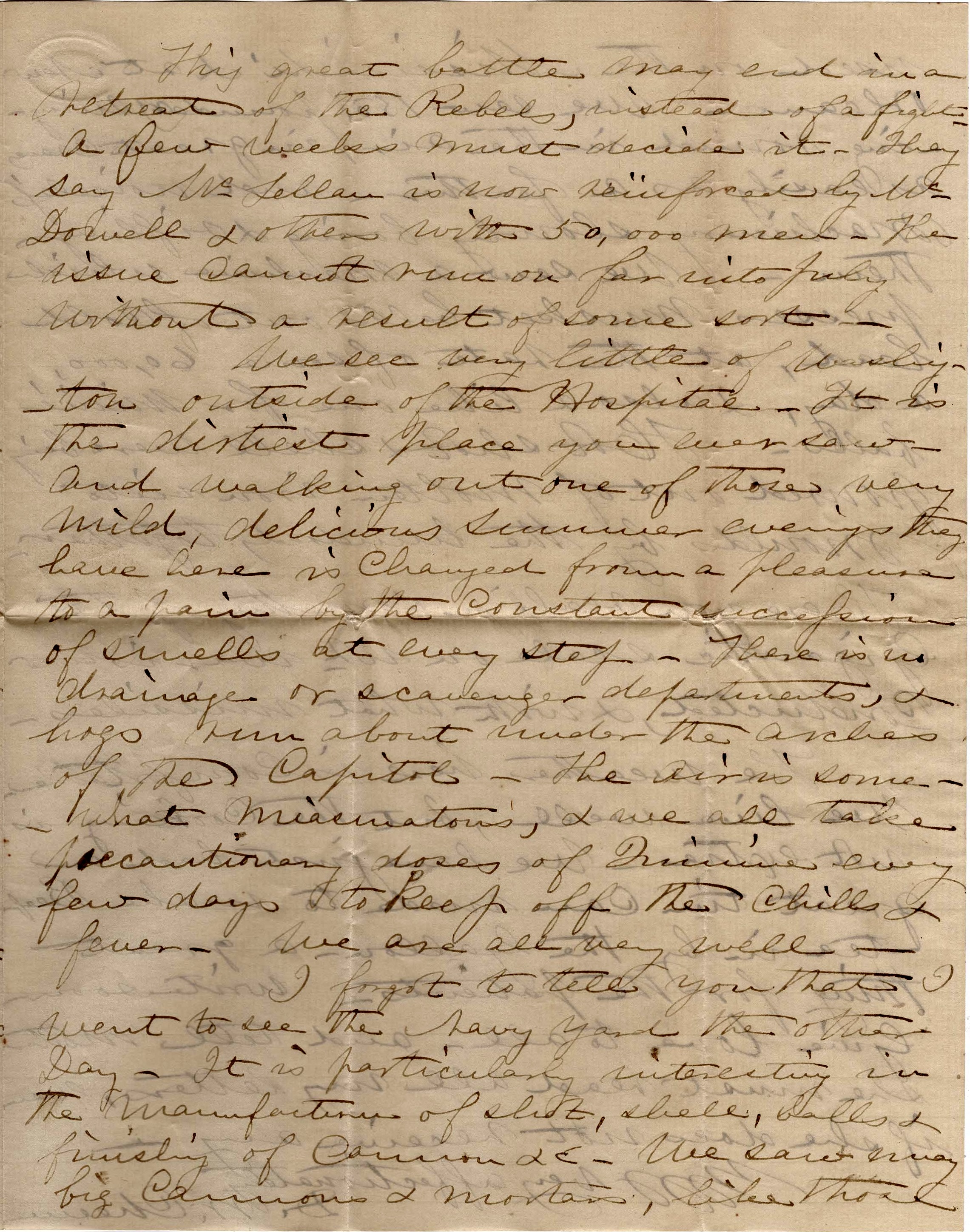

This great battle may end in a retreat of the Rebels instead of a fight. A few weeks must decide it. They say McClellan is now reinforced by McDowell and others with 50,000 men. The issue cannot run on far into July without a result of some sort.

We see very little of Washington outside of the Hospital. It is the dirtiest place you ever saw. And walking out one of those very mild, delicious summer evenings they have here is changed from a pleasure to a pain by the constant succession of smells at every step. There is no drainage or scavenger departments, and hogs run about under the arches of the Capitol. The air is somewhat miasmatous, and all take precautionary doses of quinine every few days to keep off the chills & fever. We are all very well.

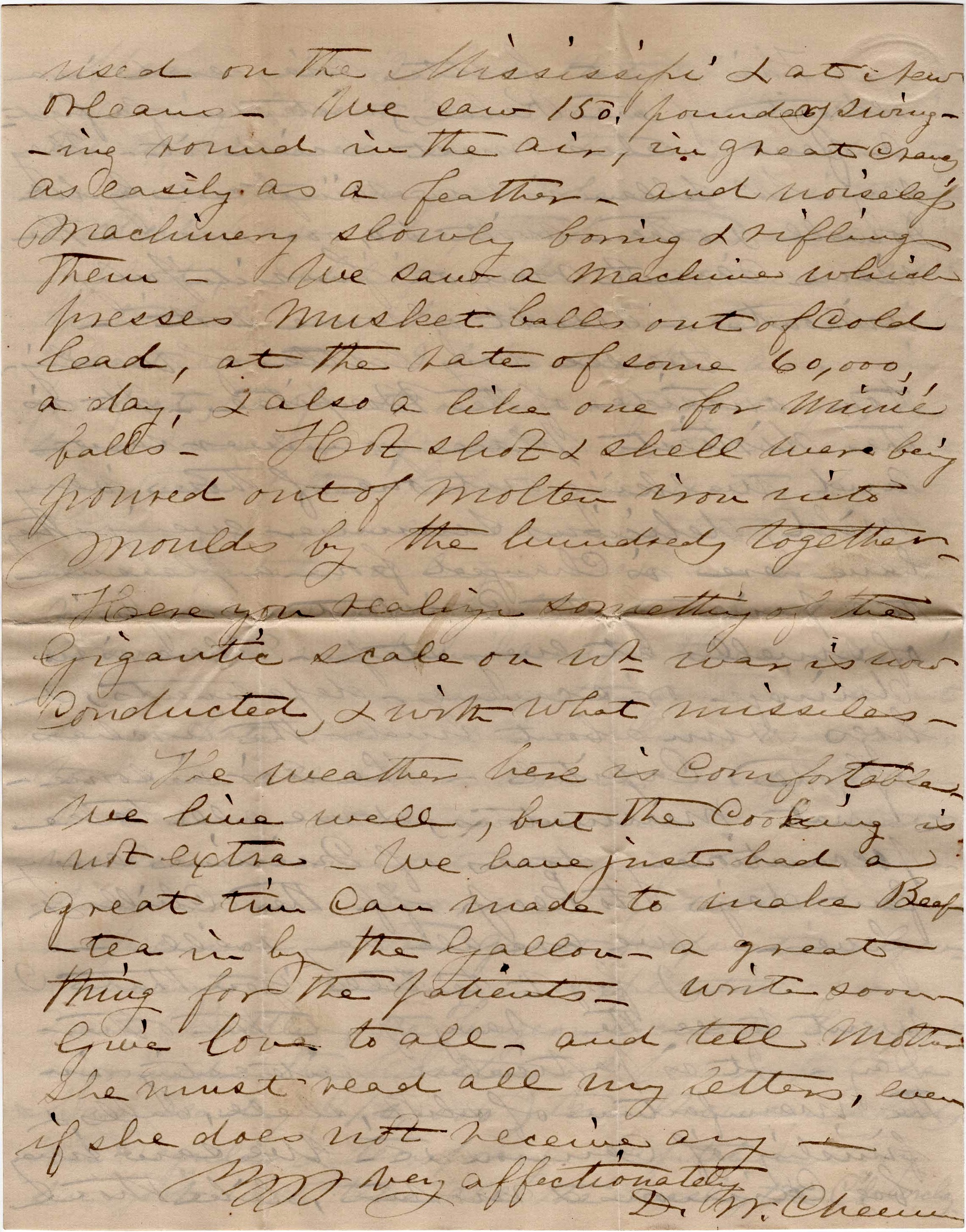

I forgot to tell you that I went to see the Navy Yard the other day. It is particularly interesting in the manufacture of shot, shell, balls and finishing of cannon &c. We saw many big cannons and mortars, like those used on the Mississippi & at New Orleans. We saw 150 pounders swinging round in the air in great cranes as easily as a feather, and noiseless machinery slowly boring and rifling them. We saw a machine which presses musket balls out of cold lead at the rate of some 60,000 a day, and also a like one for Minié balls. Hot shot and shell were being poured out of molten iron into moulds by the hundreds together. Here you realize something of the gigantic scale on which war is now conducted and with what missiles.

The weather here is comfortable. We live well but the cooking is not extra. We have just had a great tin can made to make beef tea in by the gallon—a great things for the patients. Write soon. Give love to all and tell Mother she must read all my letters even if she does not receive any.

Yours very affectionately, — D. W. Cheever

Letter 5

Washington

Sunday evening, June 29, 1862

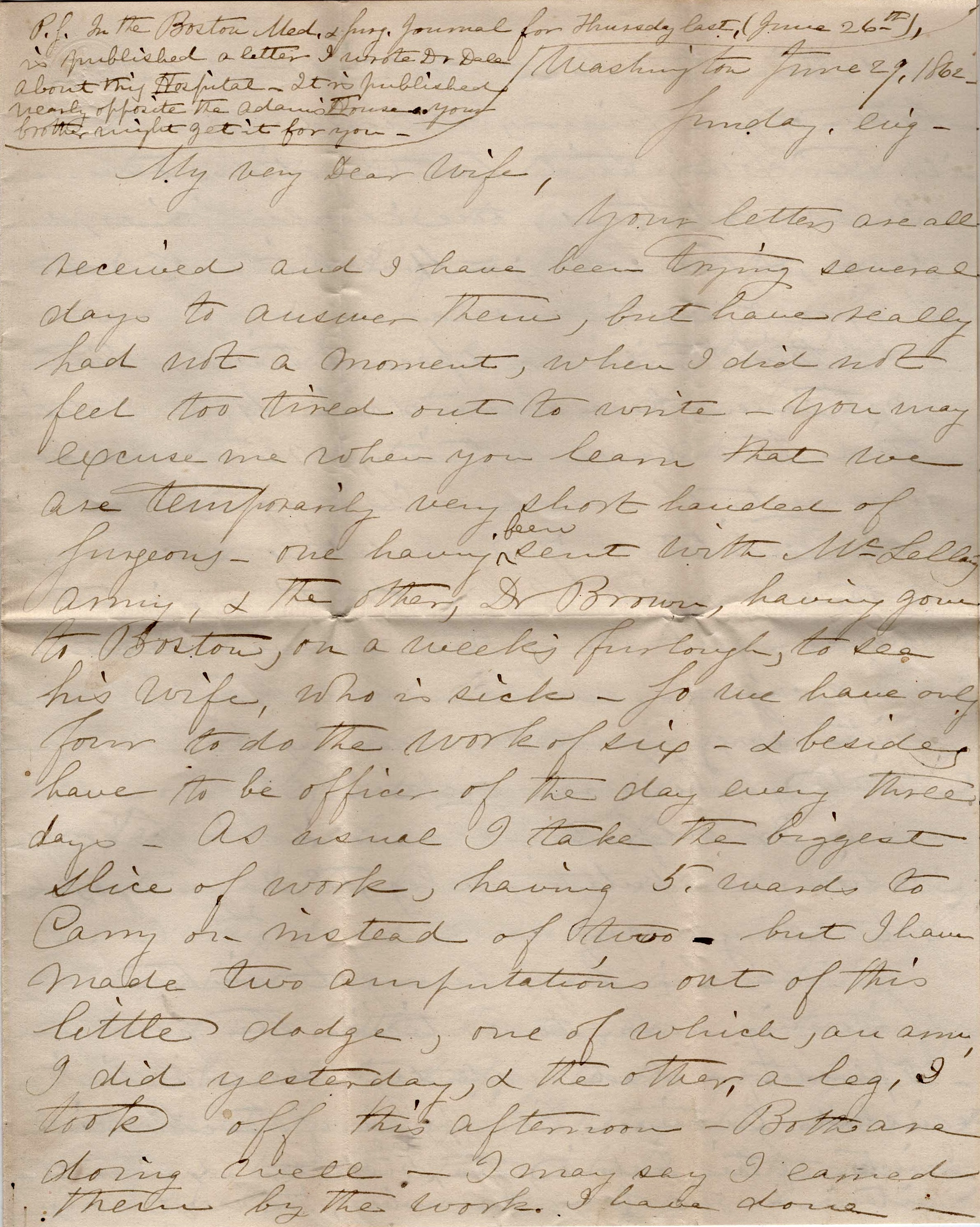

My very dear wife,

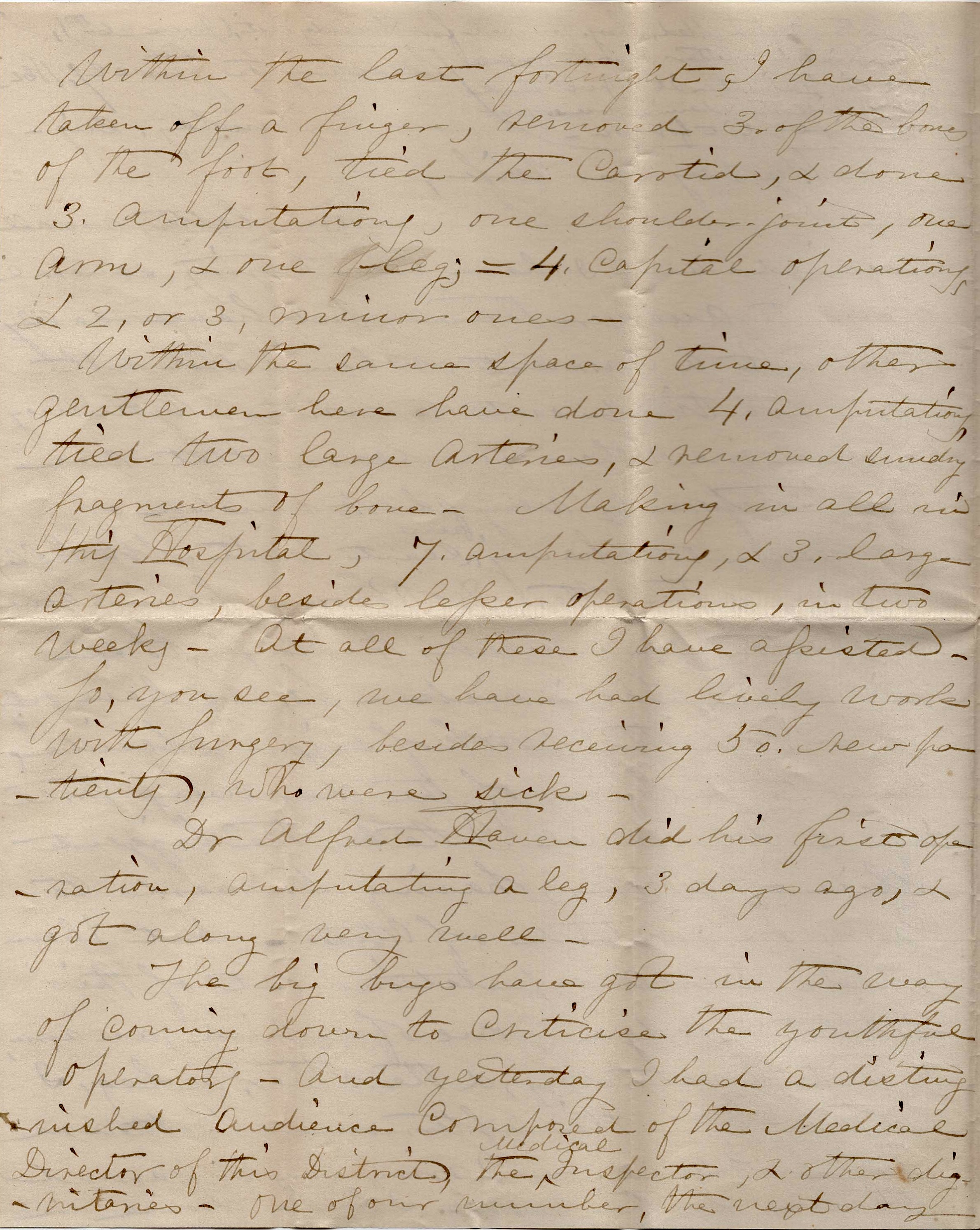

Your letters are all received and I have been trying several days to answer them, but have really had not a moment when I did not feel too tired out to write. You may excuse me when you learn that we are temporarily very short handed of surgeons—one having been sent with McClellan’s army and the other, Dr. Brown, having gone to Boston for a week’s furlough to see his wife who is sick. So we have only four to do the work of six, and besides, have to be Officer of the Day every three days. As usual, I take the biggest slice of work, having 5 wards to carry on instead of two, but I have made two amputations out of this little dodge, one of which—an arm—I did yesterday, and the other—a leg—I took off this afternoon. Both are doing well. I may say I lamed them by the work I have done. Within the last fortnight I have taken off a finger, removed three of the bones of the foot, tied the carotid, and done three amputations, one shoulder joint, one arm, and one leg—4 capital operating & 2 or 3 minor ones.

Within the same space of time, other gentlemen here have done 4 amputations, tied two large arteries, and removed sundry fragments of bone, making in all in this hospital 7 amputations and three large arteries, besides lesser operations in two weeks. At all of these I have assisted so you see we have had lively work with surgery, besides receiving 50 new patients who were sick.

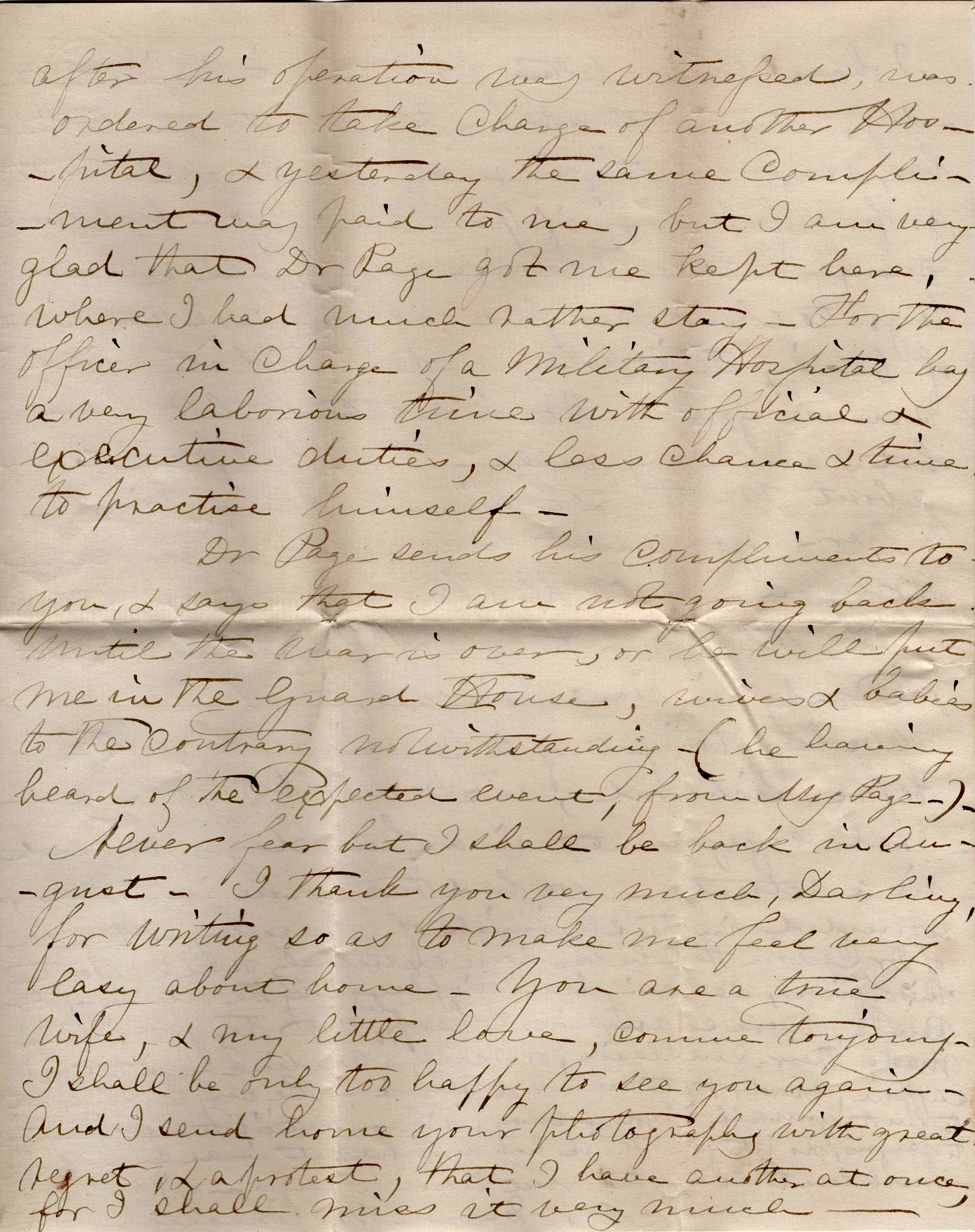

Dr. Alfred Haven did his first operation—amputating a leg—three days ago and got along very well. The big boys have got in the way of coming down to criticize the youthful operators, and yesterday I had a distinguished audience composed of the Medical Director of this District, the Medical Inspector, and other dignitaries. One of our number, the next day after his operation was witnessed, was ordered to take charge of another hospital, and yesterday the same compliment was paid to me. But I am very glad that Mr. Page got me kept here where I had much rather stay, for the officer in charge of a Military Hospital has a very laborious time with official and executive duties & less chance & time to practice himself.

Dr. [Calvin Gates] Page 1 sends his compliments to you and says that I am not going back until the war is over, or he will put me in the guard house, wives and babies to the contrary notwithstanding (he having heard of the expected event from Mrs. Page). Never fear but I shall be back in August. I thank you very much, darling, for writing so as to make me feel very easy about home. You are a true wife and my little love comme toujours [as ever]. I shall be only too happy to see you again. And I send home your photography with great regret & a protect that I have another at once for I shall miss it very much.

I have had a letter from Aunt Elizabeth today who is tolerable. She wants you to visit her and says everything is ready, &c. I would try to go for a few days if possible & you feel well enough. Also, I advise you by all means to go to New Bedford if you are confident of bearing the journey well, and if it will amuse you. It is steady hot here but I am very well. I am delighted to hear about Mother and Edwin. I have written to her. You must have a funny garden going on. Tell Rauffer not to set you on fire the 4th of July. I have no doubt the baby is very fine now.

We hear tonight of a considerable battle before Richmond which must bring on a general engagement in a few days or end in a retreat. We had two come in today wounded in the skirmish of Thursday. We hear of Dr. Crehove [?] that he has done extremely well and that his officers, he having been displaced by the return of Dr. Revere, were so anxious to keep him that they got him made their chaplain, or really a medical assistant, I suppose, under that name and rank.

Be very careful not to hurt yourself if you go away, and if you anticipate a fatiguing trip to Saugus, do not go. Think how dreadful that would be. With much love to all & the most to you, I remain your affectionate husband, — David W. Cheever

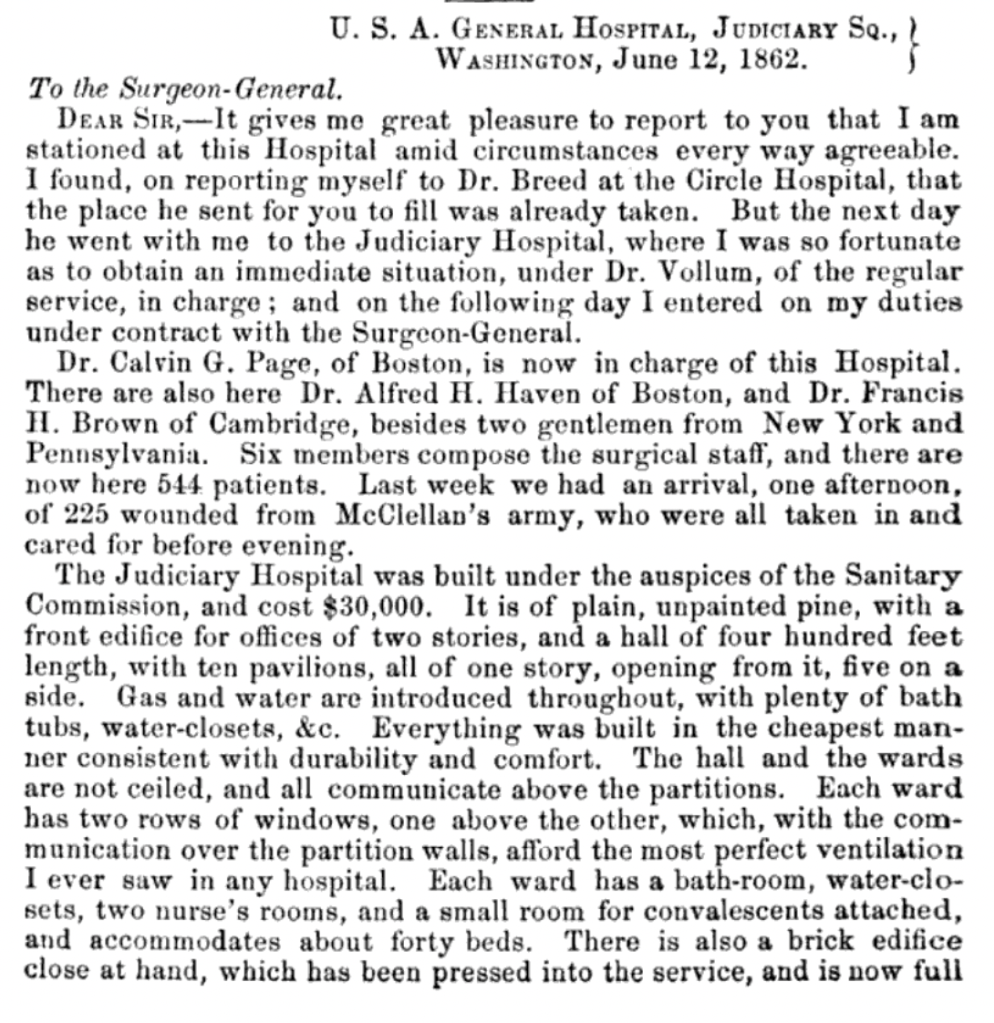

P. S. In the Boston Med. & Surgical Journal for Thursday last (June 26th) is published a letter I wrote Dr. Dale about the hospital. 2 It is published nearly opposite the Adams House. Your brother might get it for you.

1 Calvin Gates Page, Sr. (1829-1869) was a practicing physician in Boston when the Civil War began. He was married to Susan Haskell Keep (1830-1895) and was the father of three children at the time he offered his services as a surgeon at the Judiciary Square Hospital. In August 1862, he was commissioned as Assistant Surgeon in the 39th Massachusetts Infantry and served until mid-November 1863.

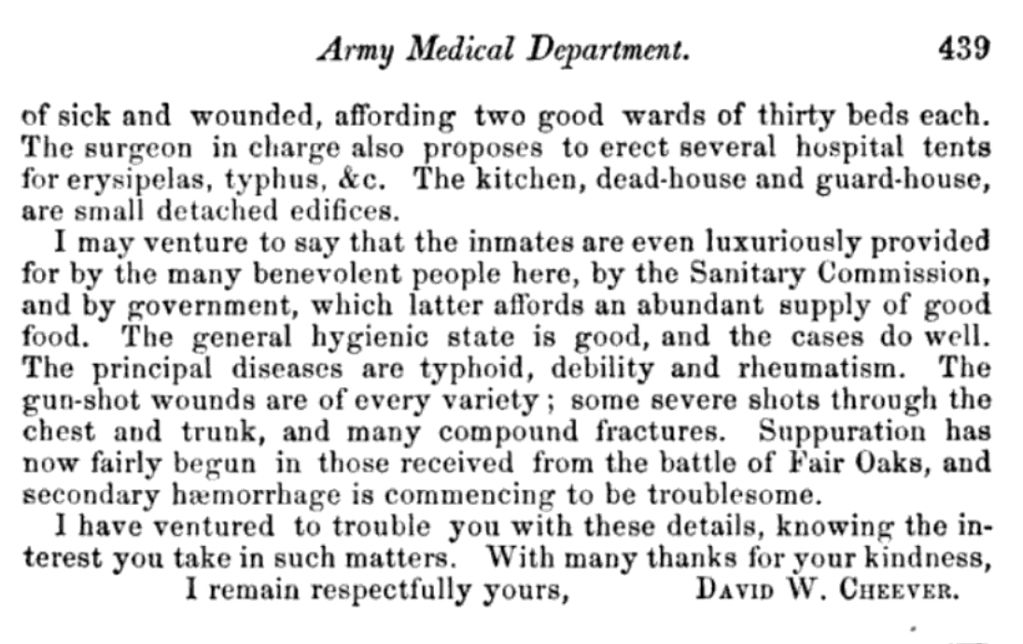

2 The letter appears below:

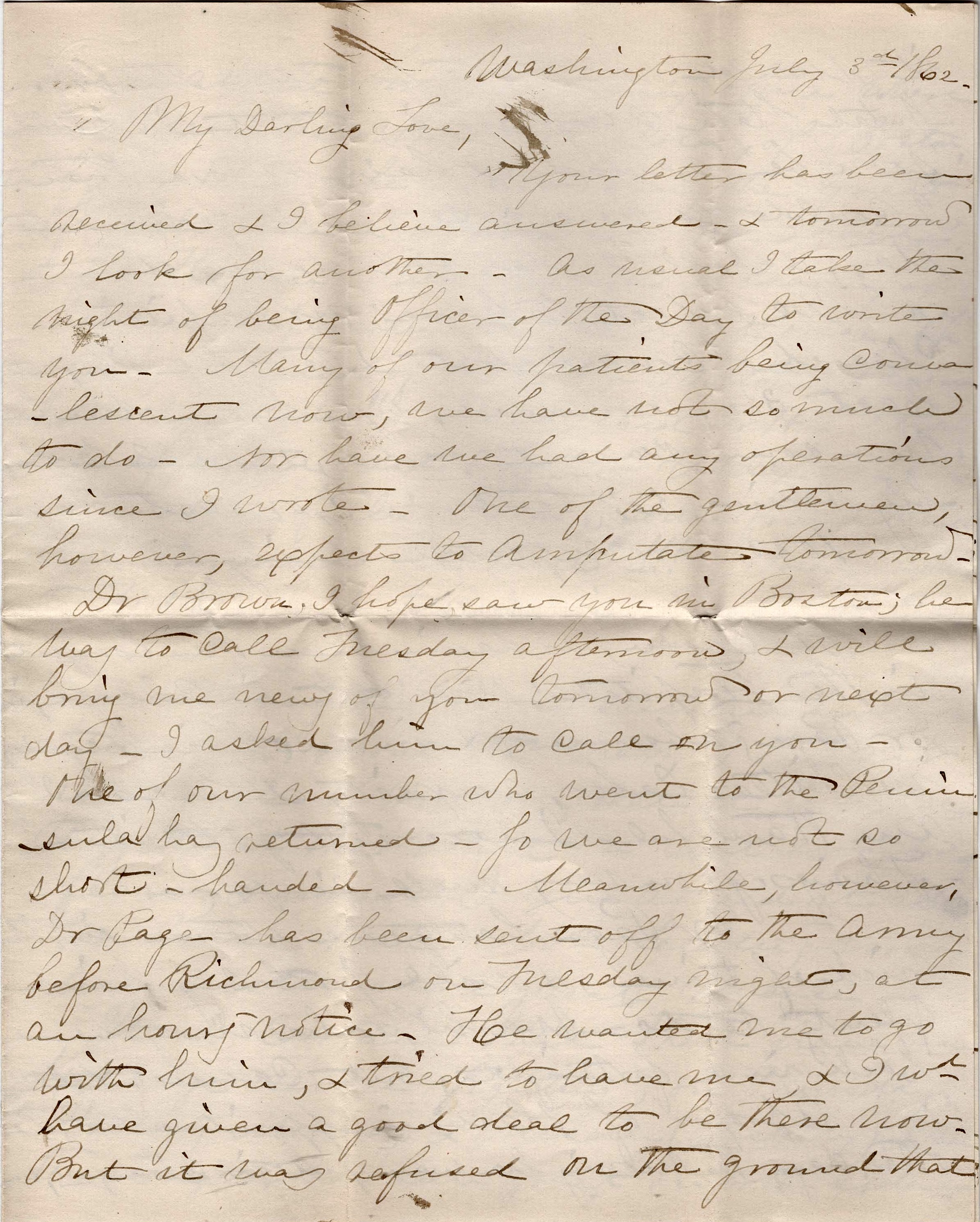

Letter 6

Washington

July 3rd 1862

My darling love,

Your letter has been received & I believe answered, and tomorrow I look for another. As usual I take the night of being Officer of the Day to write you. Many of our patients being convalescent now, we have not so much to do. Nor have we had any operations since I wrote. One of the gentlemen, however, expects to amputate tomorrow. Dr. Brown, I hope, saw you in Boston. He was to call Tuesday afternoon & will bring me news of you tomorrow or next day. I asked him to call on you.

One of our number who went to the Peninsula returned so we are not so short-handed. Meanwhile, however, Dr. [Calvin] Page has been sent off to the army before Richmond on Tuesday night at an hour’s notice. He wanted me to go with him and tried to have me & I would have given a good deal to be there now, but it was refused on the ground that it would not do to weaken the hospital staff anymore & that I should soon be needed & have more than I could do here. So I was ordered to stay and shall endeavor to do my duty.

We expect to have our hospital cleared of convalescents & to take in at least 300 wounded by and bye. We have now some vacant beds & shall probably receive 50 wounded tomorrow or next day. 1,000 are expected daily.

Dr. [Alfred] Haven, having been the longest in the hospital, was left in charge in Dr. Page’s absence, and in an office requiring no little labor, anxiety & fuss, I am thankful I have not got it. Things go on very well so far. Dr. Page has gone down in the nick of time & will probably find plenty to do. We hope he may be back in a fortnight but cannot tell.

Apropos of having appointment the other day, the morning he was put in charge, we were at the Surgeon General’s Office where we saw the immortal Cole of Boston, bigger than life, and surveying the Great Officials like a Prince. He asked Dr. Haven where he was, and learning of his new appointment, said at once, “Oh yes! We heard of that in Boston, and were much pleased.” “But,” said Dr. Haven, “I was only appointed last evening.” “Well,” replied the never-failing Cole, “Some friend must have telegraphed it then!” Query? When? to Boston and back to Cole in Washington?

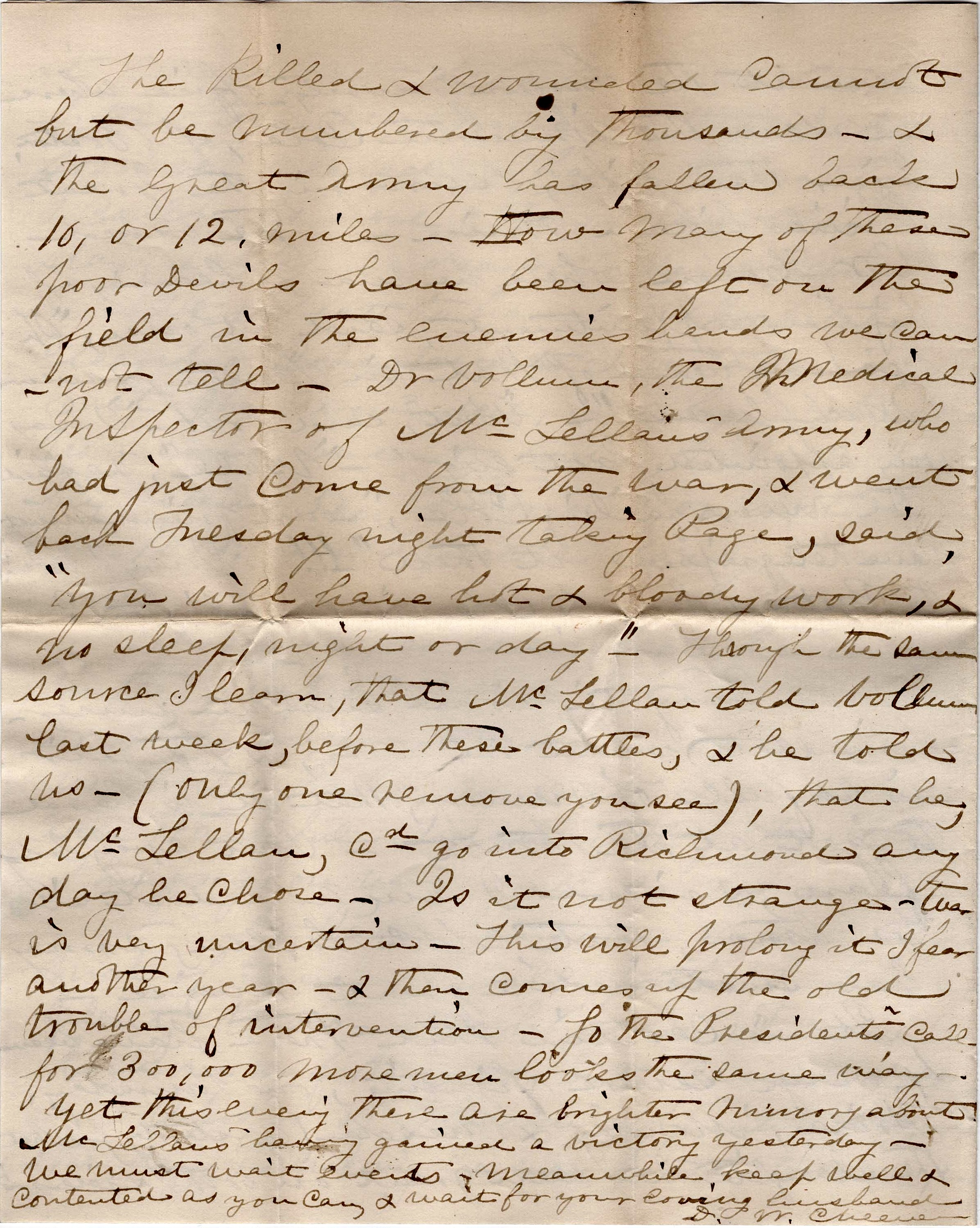

Everything is in such an uncertain state about the war, and the air is so full of rumors that it is hard to get at the truth. But everybody fears—and indeed, I am afraid it is too true—that McClellan’s army has sustained a great reverse. It is certain that there have been four days severe fighting, on Thursday, Friday, Monday & Tuesday (yesterday) and that the slaughter has been great on both sides. The killed and wounded cannot but be numbered by thousands & the Great Army has fallen back 10 or 12 miles. How many of these poor devils have been left on the field in the enemies hands we cannot tell.

Dr. [Edward Perry] Vollum, the Medical Inspector of McClellan’s army, who had just come from the war and went back Tuesday night taking Page, said, “You will have hot & bloody work and no sleep, night or day.” Through the same source I learn that McClellan told Vollum last week before these battles, & he told us (only one remove, you see), that he—McClellan—could go into Richmond any day he chose. Is it not strange—war is very uncertain. This will prolong it I fear another year, and then comes up the old trouble of [foreign] intervention. So the President’s call for 300,000 more men looks the same way. Yet this evening there are brighter rumors about McClellan’s having gained a victory yesterday. We must wait events. Meanwhile, keep well and contented as you can & wait for your loving husband, — D. W. Cheever

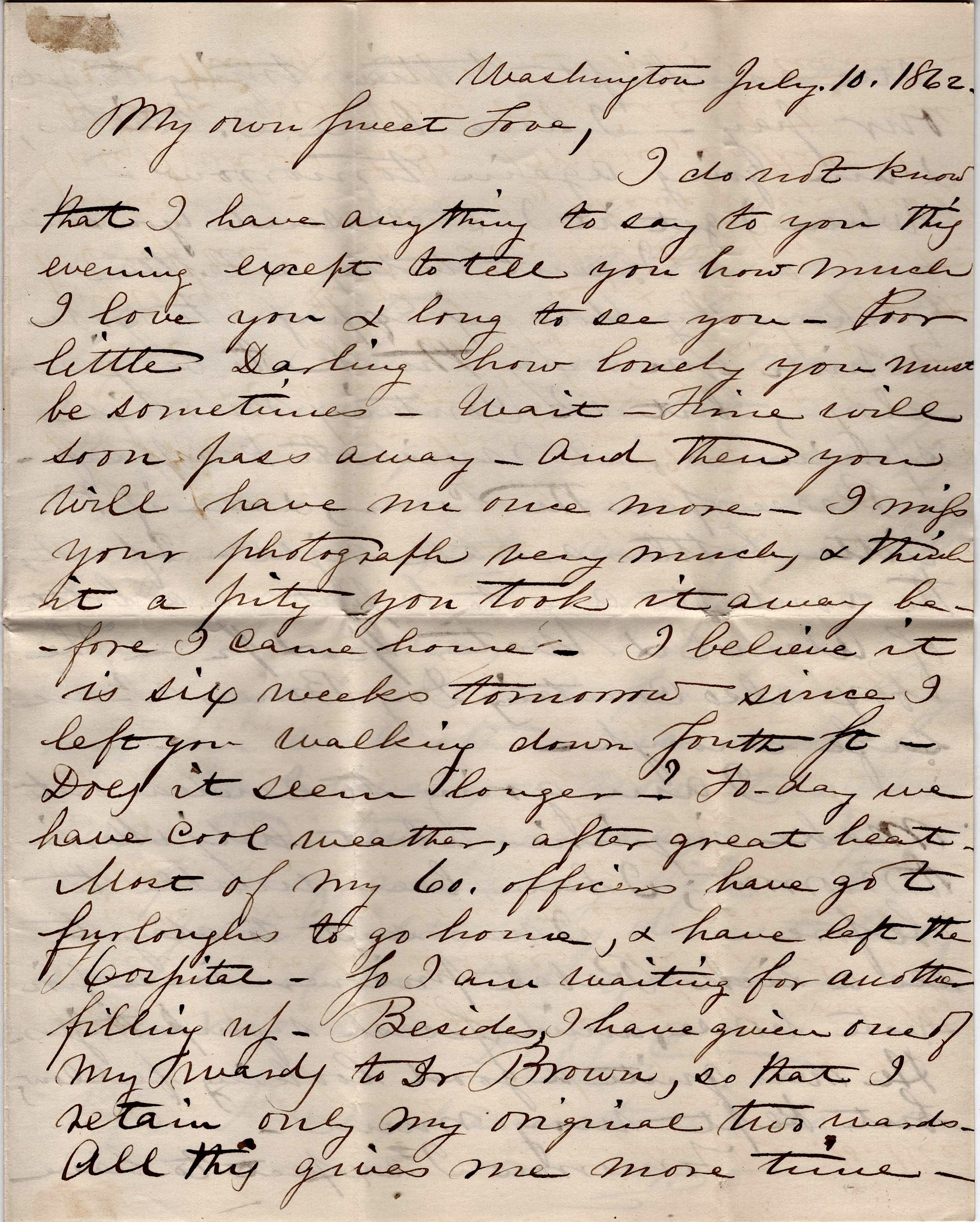

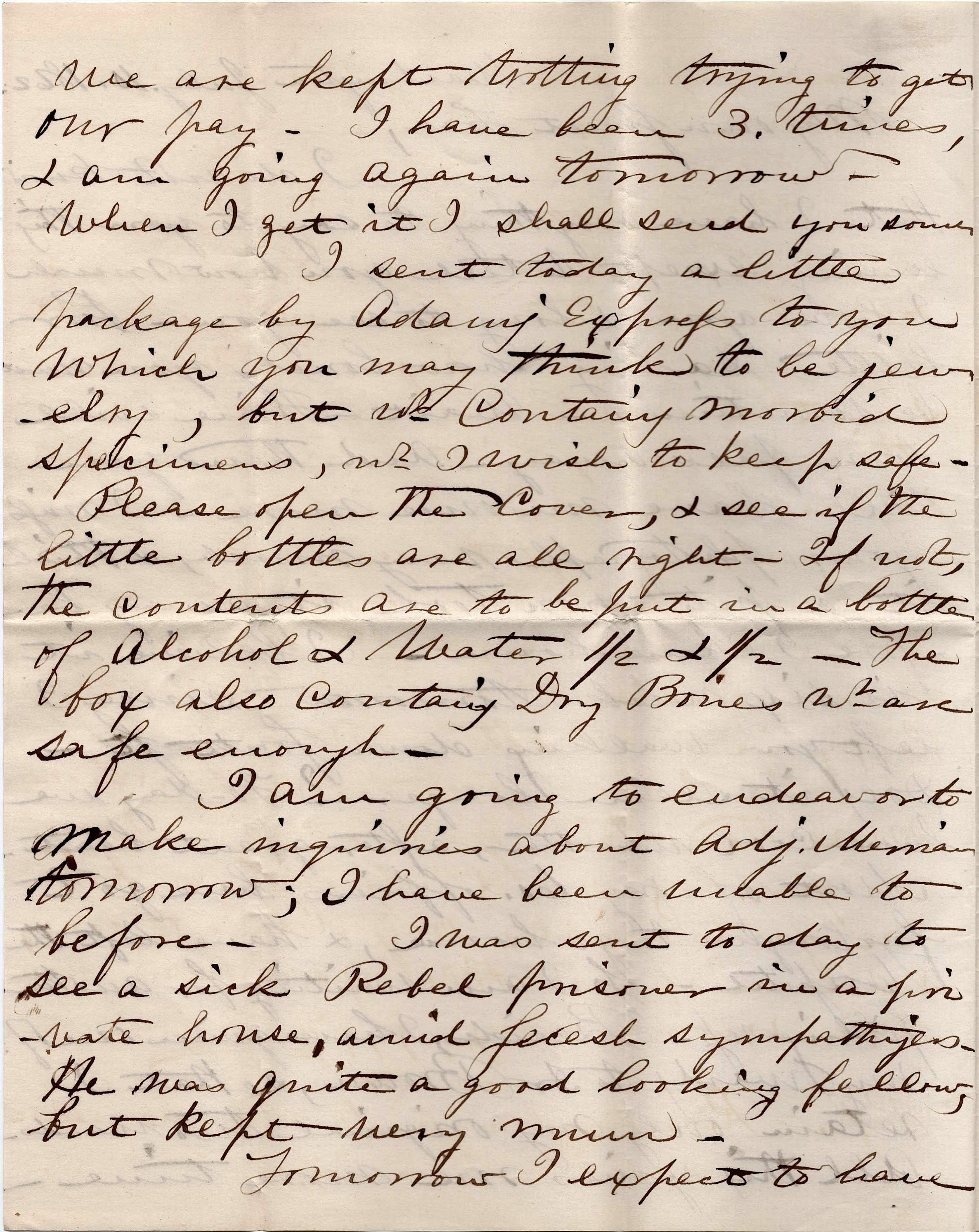

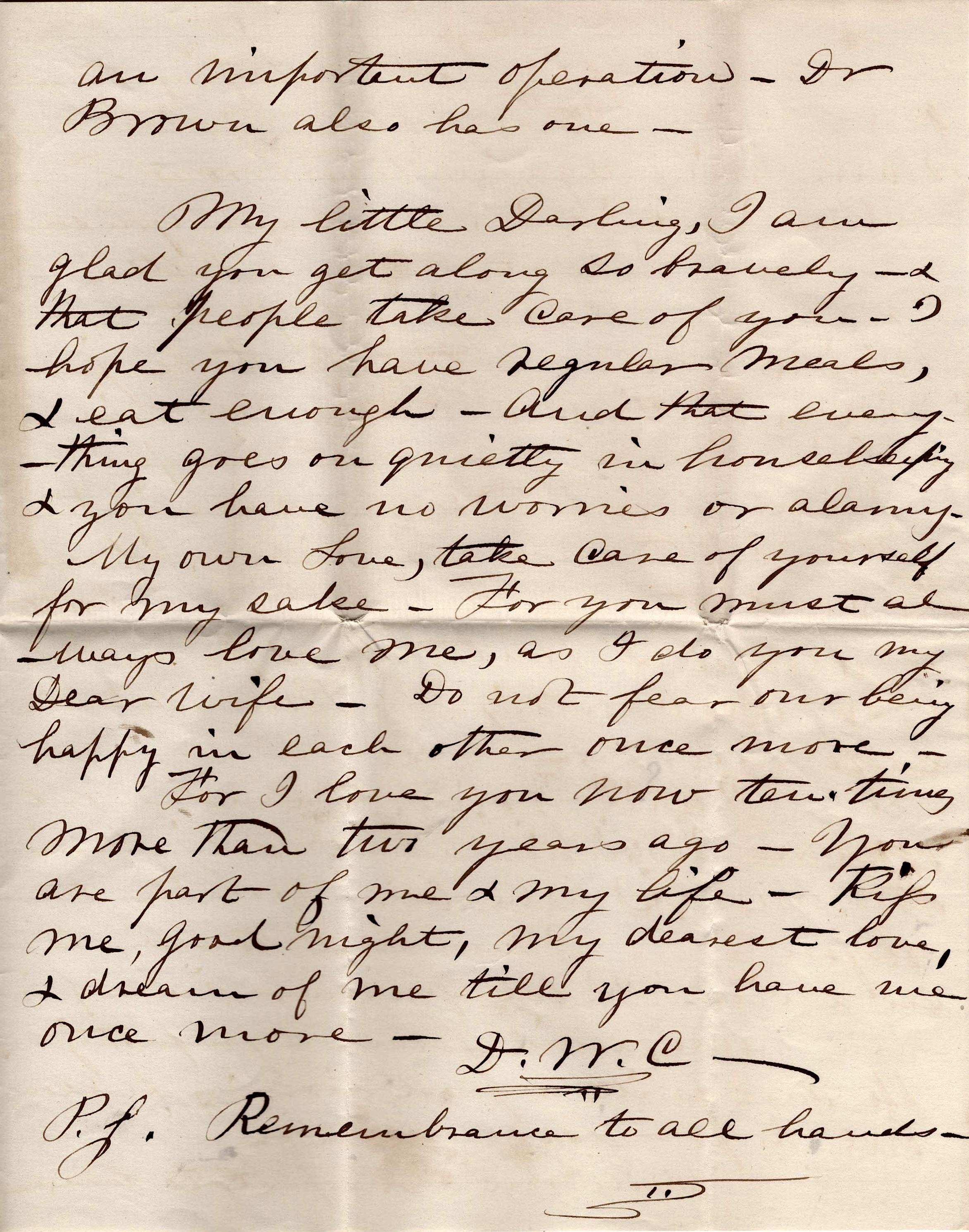

Letter 7

Washington

July 10, 1862

My own sweet love,

I do not know that I have anything to say to you this evening except to tell you how much I love you and long to see you. Poor little darling, how lonely you must be sometimes. Wait. Time will soon pass away and then you will have me once more. I miss your photograph very much & think it a pity you took it away before I came home. I believe it is six weeks tomorrow since I left you, walking down Fourth Street. Does it seem longer?

Today we have cool weather after great heat. Most of my 60 officers have got furloughs to go home and have left the hospital so I am waiting for another filling up. Besides, I have given one of my wards to Dr. Brown so that I retain only my original two wards. All this gives me more time. We are kept trotting trying to get our pay. I have been three times and am going again tomorrow. When I get it, I shall send you some.

I sent today a little package by Adam’s Express to you which you may think to be jewelry, but which contains morbid specimens which I wish to keep safe. Please open the cover and see if the little bottles are all right. If not, the contents are to be put in a bottle of alcohol and water half and half. The box also contains dry bones which are safe enough.

I am going to endeavor to make inquiries about Adj. Merriam tomorrow; I have been unable to before. I was sent today to see a sick Rebel prisoner in a private house amid secesh sympathizers. He was quite a good looking fellow but kept very mum.

Tomorrow I expect to have an important operation. Dr. Brown also has one.

My little darling, I am glad you get along so bravely and that people take care of you. I hope you have regular meals & eat enough and that everything goes on quietly in housekeeping & you have no worries or alarms. My own love, take care of yourself for my sake, for you must always love me as I do you, my dear wife. Do not fear our being happy in each other once more. For I love you now then times more than two years ago. You are part of me & my life. Kiss me good night, my dearest love, and dream of me till you have me once ore. — D. W. C.

P. S. Remembrance to all hands.

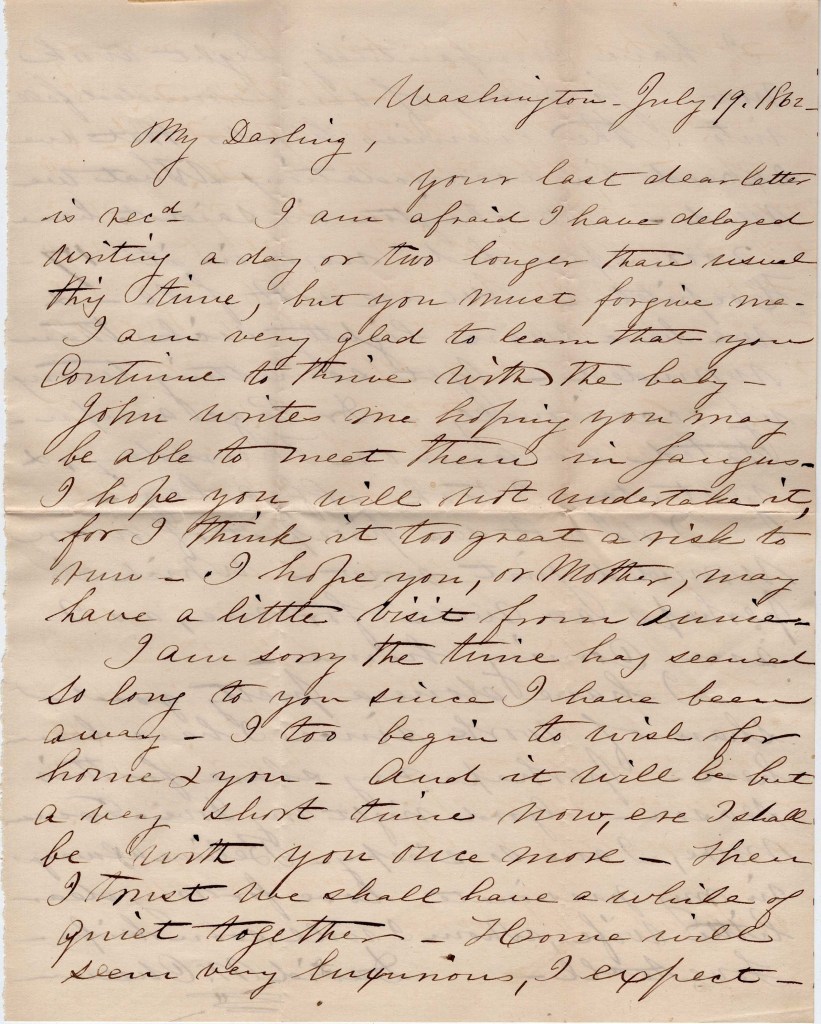

Letter 8

Washington

July 19, 1862

My darling,

Your last dear letter is received. I am afraid I have delayed writing a day or two longer than usual this time but you must forgive me. I am very glad to learn that you continue to throve with the baby. John writes me hoping you may be able to meet them in Saugus. I hope you will not undertake it, for I think it too great a risk to run. I hope you or Mother may have a little visit from Annie.

I am sorry the time has seemed so long to you since I have been away. I too begin to wish for hime and you. And it will be but a very short time now, ere I shall be with you once more. Then I trust we shall have a while of quiet time together. Home will seem very luxurious, I expect.

I have comparatively light work now. So many of our wounded fell into the enemies hands that we exceed in accommodations what we need. Washington is said to have 2,000 spare beds now in its 17 hospitals. We are not full and we have more lightly sick than wounded. Yet something turns up occasionally. Dr. Page amputated an arm on Thursday & yesterday I took off a leg. I do not see prospect of more wounded just now, which is perhaps as well for me as I am coming home.

I have done a pretty good share of work since I have ben here—perhaps my share for this season. Good night my dove. Excuse more, I am so sleepy. Believe always in my passionate love for my dear little wife whom I will soon kiss. Love to all. — David W. Cheever

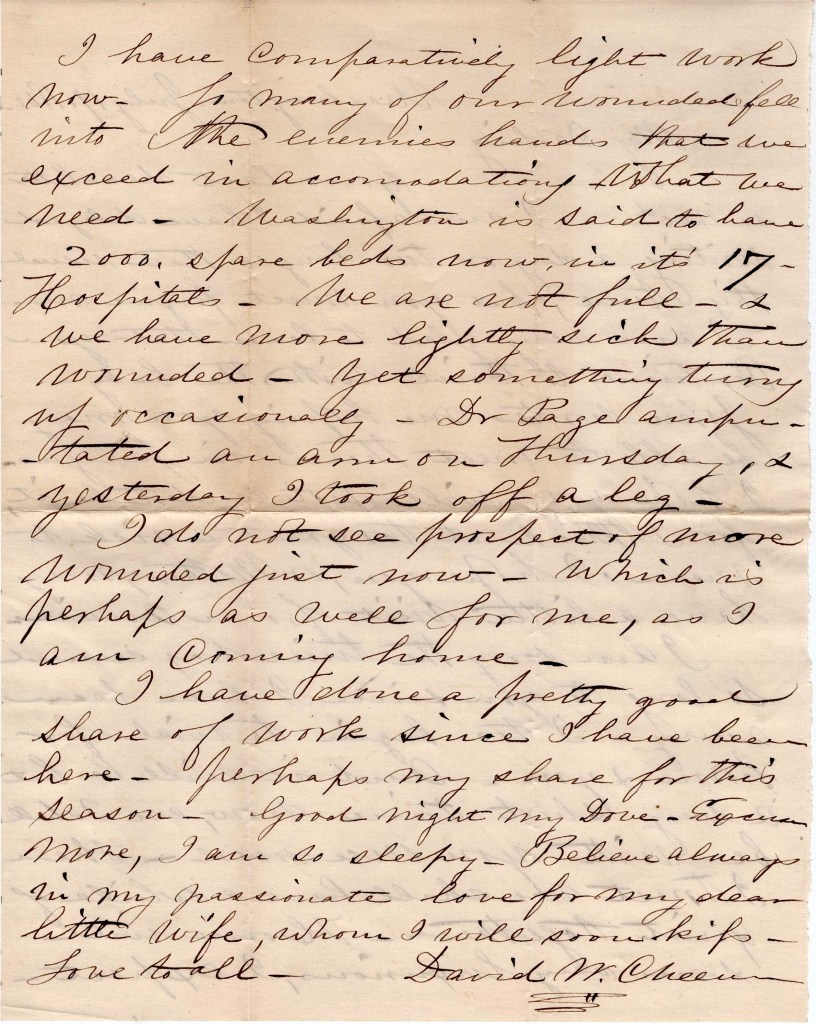

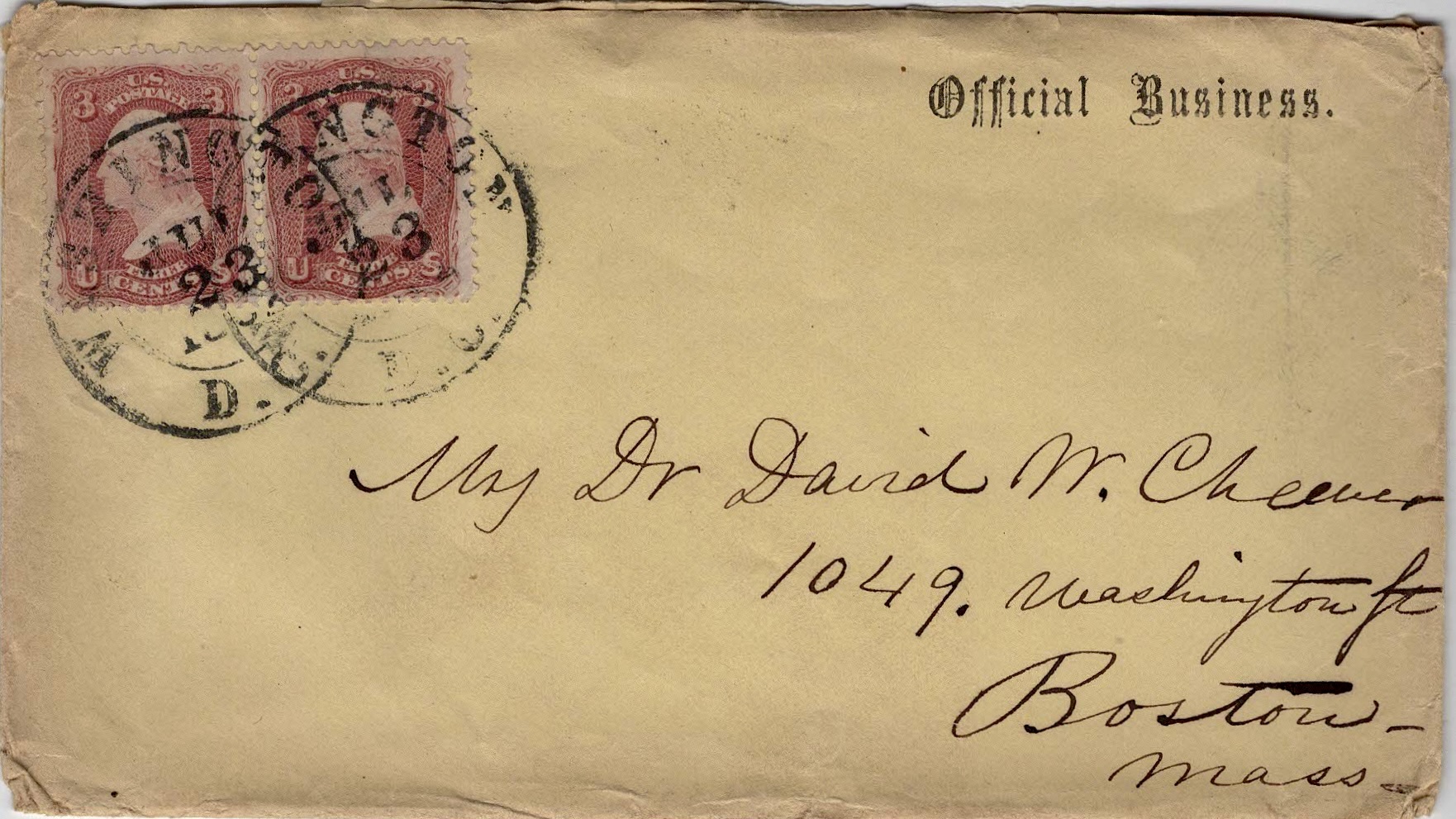

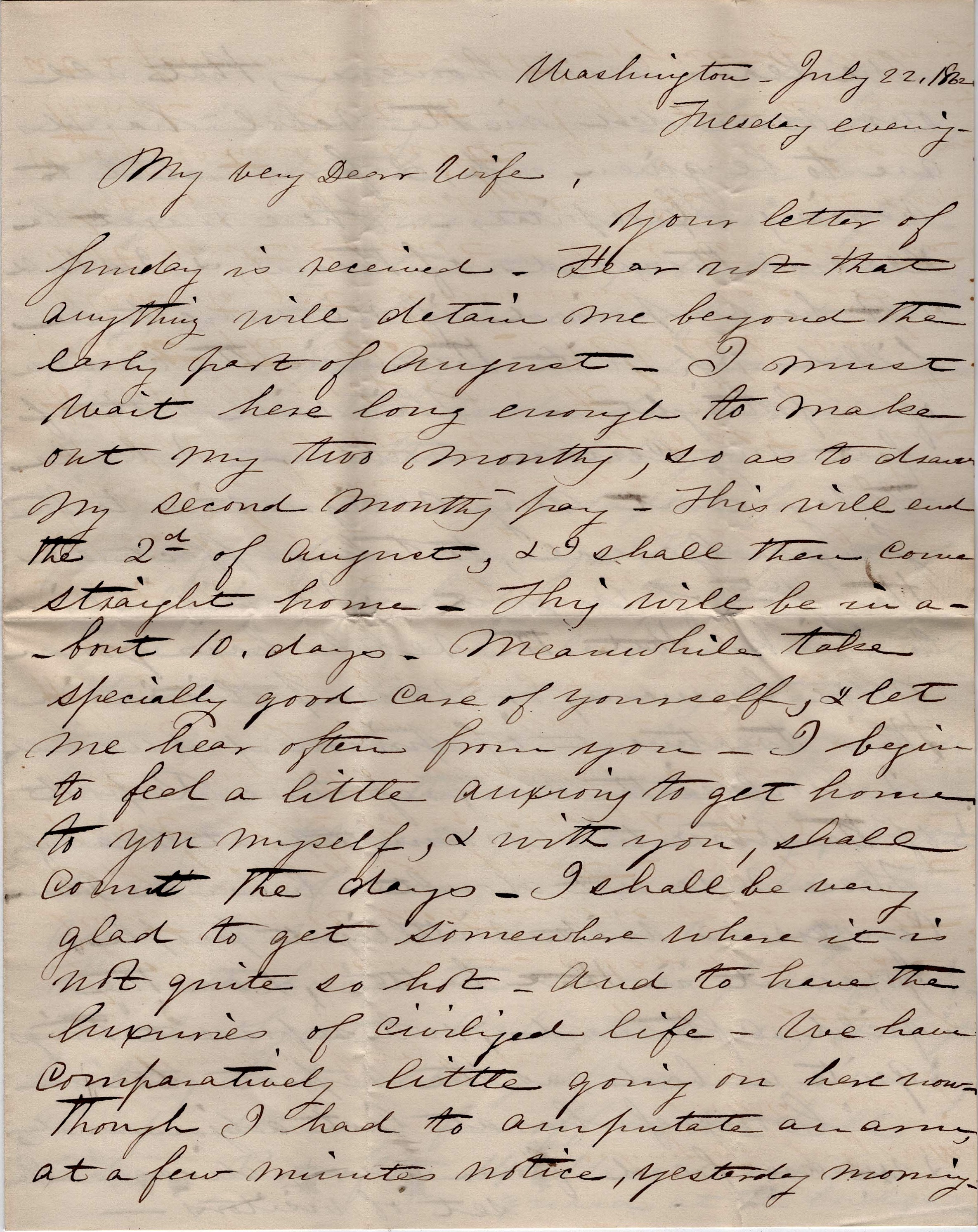

Letter 9

Washington

Tuesday evening, July 22, 1862

My very dear wife,

Your letter of Sunday is received. Fear not that anything will detain me beyond the early part of August. I must wait here long enough to make out my two months so as to draw my second month’s pay. This will end the 2nd of August & I shall then come straight home. This will be in about ten days. Meanwhile, take specially good care of yourself and let me hear often from you. I begin to feel a little anxious to get home to you myself, and with you shall count the days. I shall be very glad to get somewhere where it is not quite so hot, and to have the luxuries of civilized life.

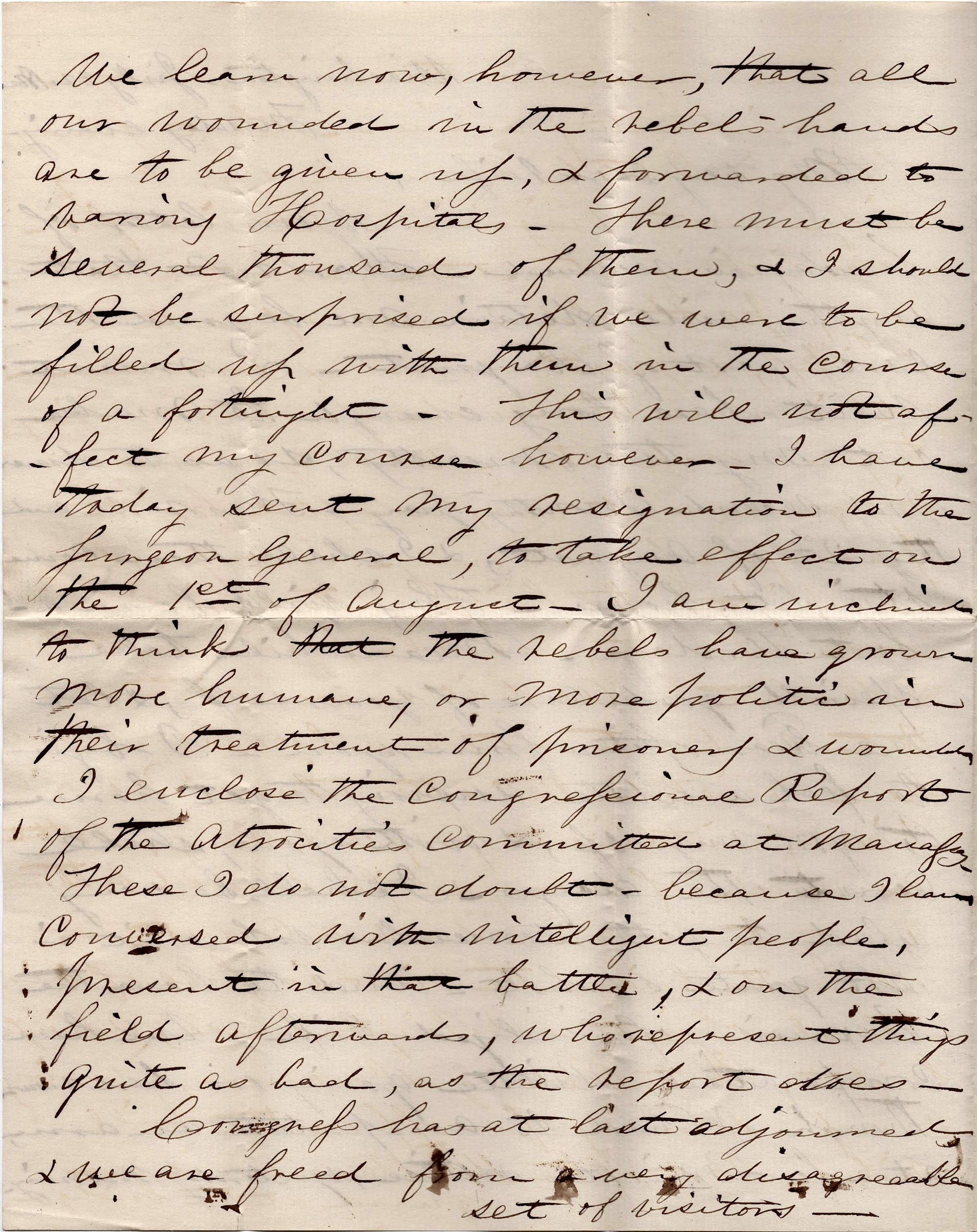

We have comparatively little going on here now though I had to amputate an arm at a few minute’s notice yesterday morning. We learn now, however, that all our wounded in the rebels’ hands are to be given up and forwarded to various hospitals. There must be several thousand of them and I should not be surprised if we were to be filled up with them in the course of a fortnight. This will not affect my course, however. I have today sent my resignation to the Surgeon General to take effect on the 1st of August. I am inclined to think that the rebels have grown more humane or more politic in their treatment of prisoners & wounded. I enclose the Congressional Report of the Atrocities committed at Manassas. These I do not doubt because I have conversed with intelligent people present in that battle & on the field afterwards who represent things quite as bad as the report does.

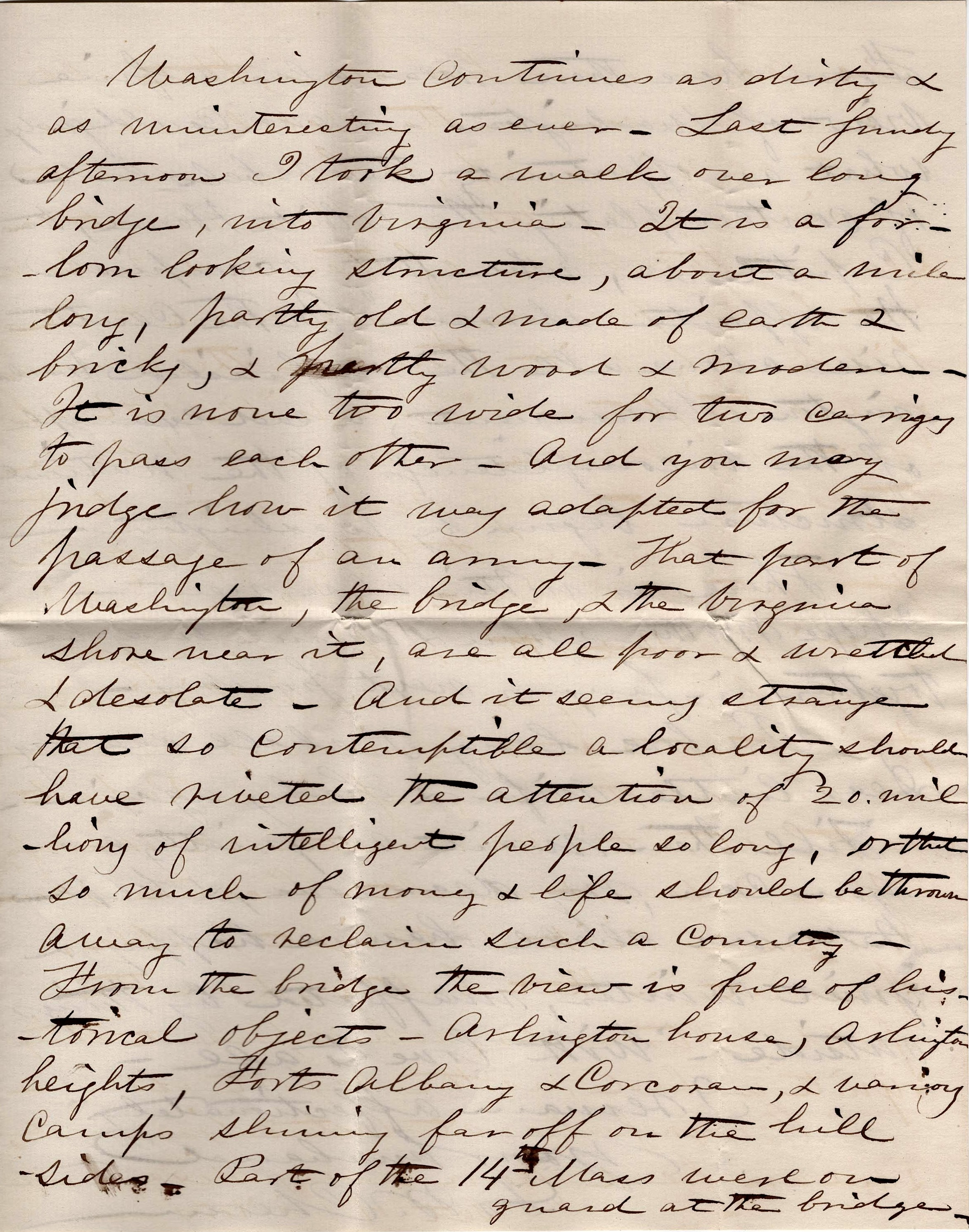

Congress has at last adjourned and we are freed from a very disagreeable set of visitors. Washington continues as dirty and as uninteresting as ever. Last Sunday afternoon I took a walk over Long Bridge into Virginia. It is a forlorn looking structure about a mile long, partly old and made of earth and bricks, and partly wood and modern. It is none too wide for two carriages to pass each other, and you may judge how it may be adapted for the passage of an army. That part of Washington, the bridge, and the Virginia shore near it, are all poor and wretched and desolate. And it seems strange that so contemptible a locality should have riveted the attention of 20 millions in intelligent people so long, or that so much of money & life should be thrown away to reclaim such a country.

From the bridge the view is full of historical objects—Arlington house, Arlington Heights, Forts Albany & Corcoran, and various camps shining far off on the hillsides. Part of the 14th Massachusetts were on guard at the bridge. From here there was also a fine view of Washington, and one could judge what an opportunity the rebels had of contemplating the White House, the Capitol, &c. when they occupied the opposite shores. In the center rises above all the unfinished Washington Monument—a sad example of the incompleteness of the National structure begun by Washington.

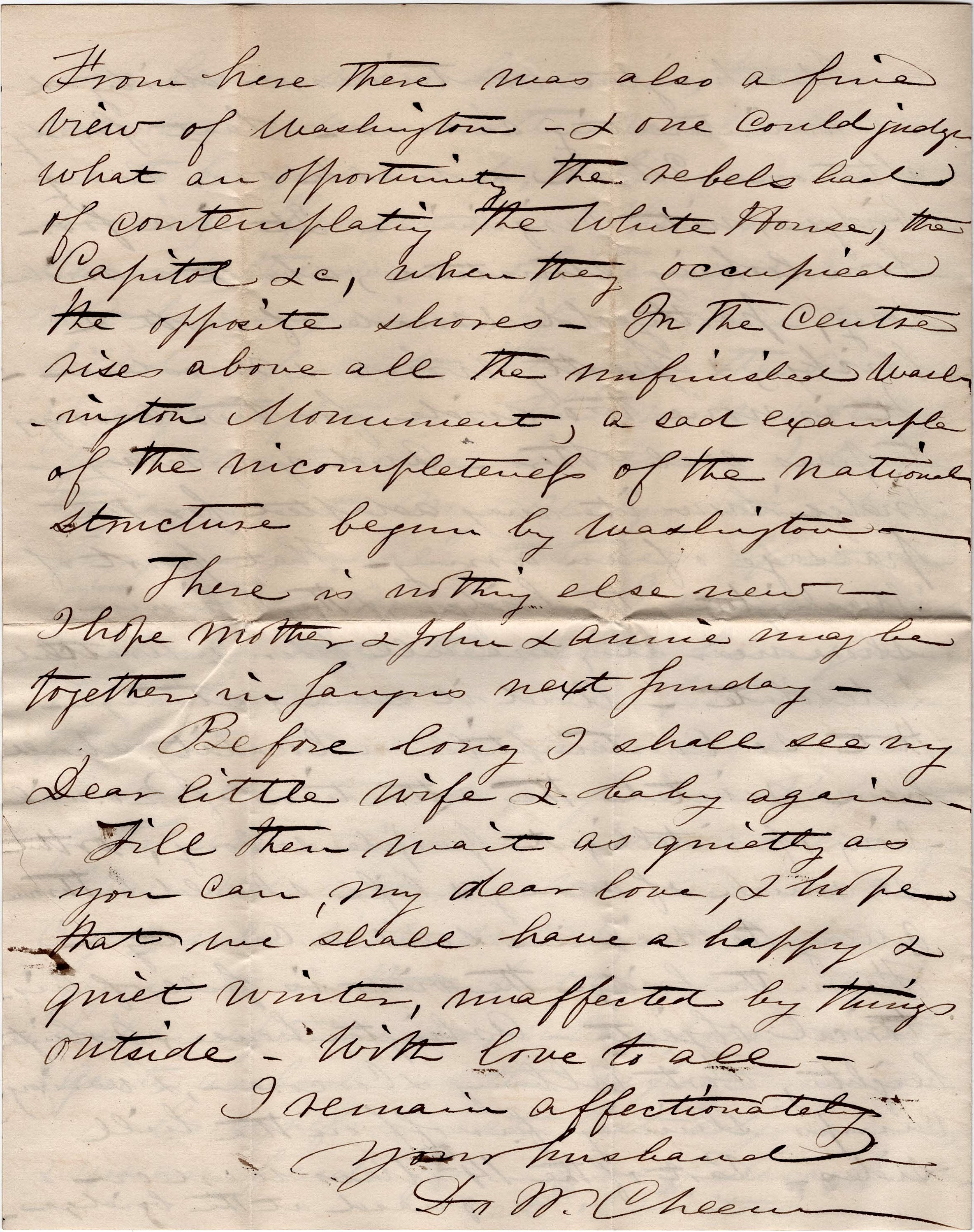

There is nothing else new. I hope Mother and John & Annie may be together in Saugus next Sunday. Before long I shall see my dear little wife and baby again. Till then, wait as quietly as you can, my dear love. I hope that we shall have a happy & quiet winter, unaffected by things outside. With love to all. I remain affectionately your husband, — D. W. Cheever

Letter 10

Washington

Sunday evening, July 27, 1862

My own love,

As I am Officer of the Day, you will expect the usual letter. I hope to get one from you tomorrow.

Drs. [Alfred] Haven and [Frank] Brown were suddenly ordered to the Peninsula yesterday to take down a party of nurses. We hope they will be back in a few days so we have a little more to do again.

Yesterday we had a visit from the President & wife. 1 They came in very quietly, dressed in mourning, & the President went round & shook hands with each of the 400 patients. Quite a job. 2

Mrs. L[incoln] is quite an inferior appearing person. The President is tall & ungainly & awkward. His face, however, shows extreme kindness, & honesty, & shrewdness. He went round with great perseverance, & seemed to like to do it, though it must be a tremendous bore. His wife says he will do it at all the hospitals. There are some things comical about him but he has proved himself so far above his party & the time in firmness, honor & conservatism that I do not wish to say a word against him. They had a very plain carriage & attendants.

Today we had preaching in the hospital in the afternoon, which went off pretty well. There are many rumors about Jackson’s being at Gordonsville with a large force, & being about to make a demonstration on Washington. It would not be surprising if they did.

My little dove, do you want to see me? I hope you will have me next Sunday. What will you do? Don’t get too excited & get into mischief. I will try to write again. Yours with everlasting love, — D. W. Cheever

1 Lincoln’s visit to the Judiciary Square Hospital must have taken some time yet the visit but it was not recorded (yet) on the Lincoln Log, the Daily Chronology of the Life of Abraham Lincoln.

2 The hospitals were sometimes part of the afternoon rides taken by Mr. & Mrs. Lincoln. One observer noted: “Mr. Lincoln’s manner was full of the geniality and kindness of his nature. Wherever he saw a soldier who looked sad and ‘down-hearted,’ he would take him by the hand and speak words of encouragement and hope. The poor fellows’ faces would lighten up with pleasure when he addressed them, and he scattered blessings and improved cheerfulness wherever he went.” [Source: Charles Bracelen Flood, 1864: Lincoln at the Gates of History, p. 101.]