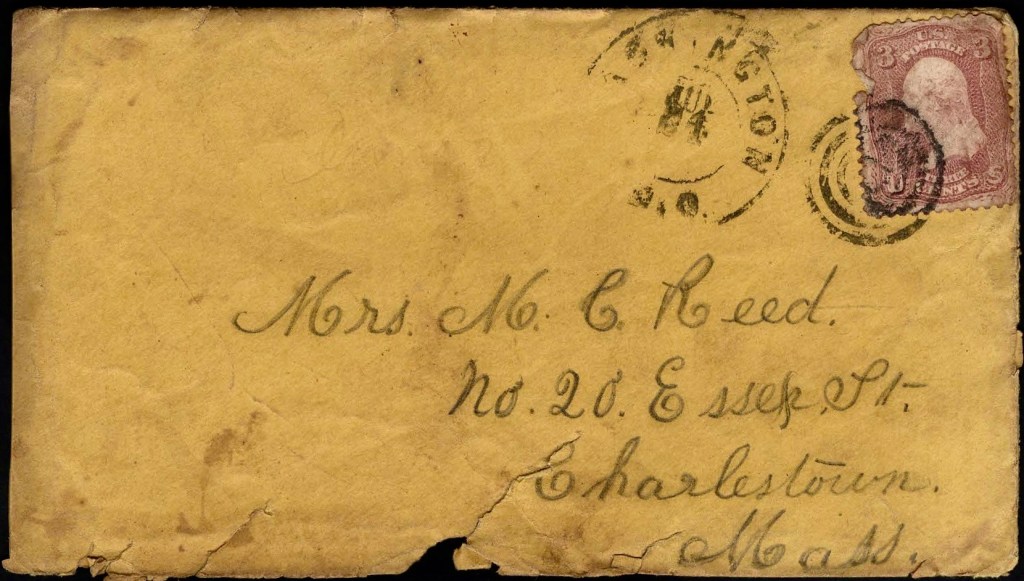

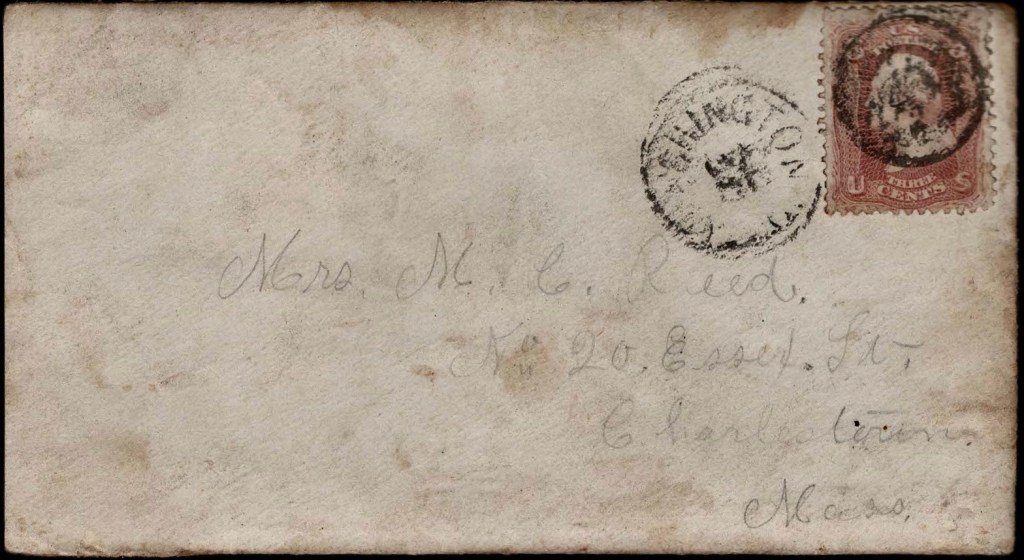

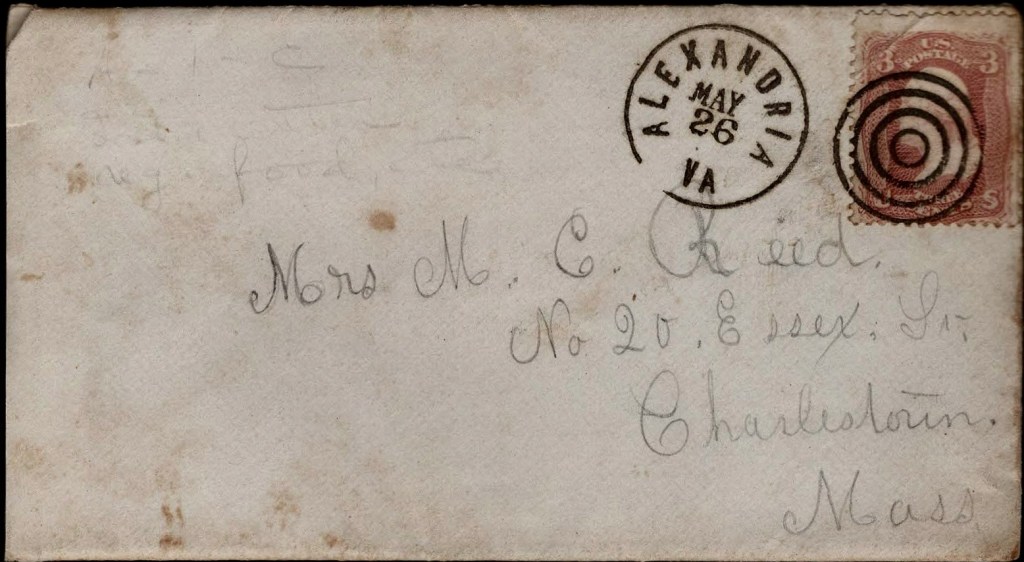

The following fifteen letters were written by Joseph Martin Reed (1845-1927), the son of Joseph W. Reed (1821-1898) and Mehitable C. Wyman of Charlestown, Massachusetts. Joseph enlisted as a private on 29 December 1863 to serve in the 11th Massachusetts Battery. He survived the war and mustered out on 16 June 1865 at Camp Meigs, Readville, Massachusetts.

Joseph’s obituary states that he was born in Woburn and that he enlisted before he was 18 years old. After he was discharged, he returned to Massachusetts and was employed as a conductor on the Eastern Railroad, running from Boston to Rockport. He married Ellen Eames, daughter of Ezra Eames, a well-known granite magnate of his time, and made his home in Rockport. Joseph’s father worked as a teamster in Charlestown for most of his life. Joseph’s parents home at 20 Essex Street in Cambridge still stands, built in the 1850s.

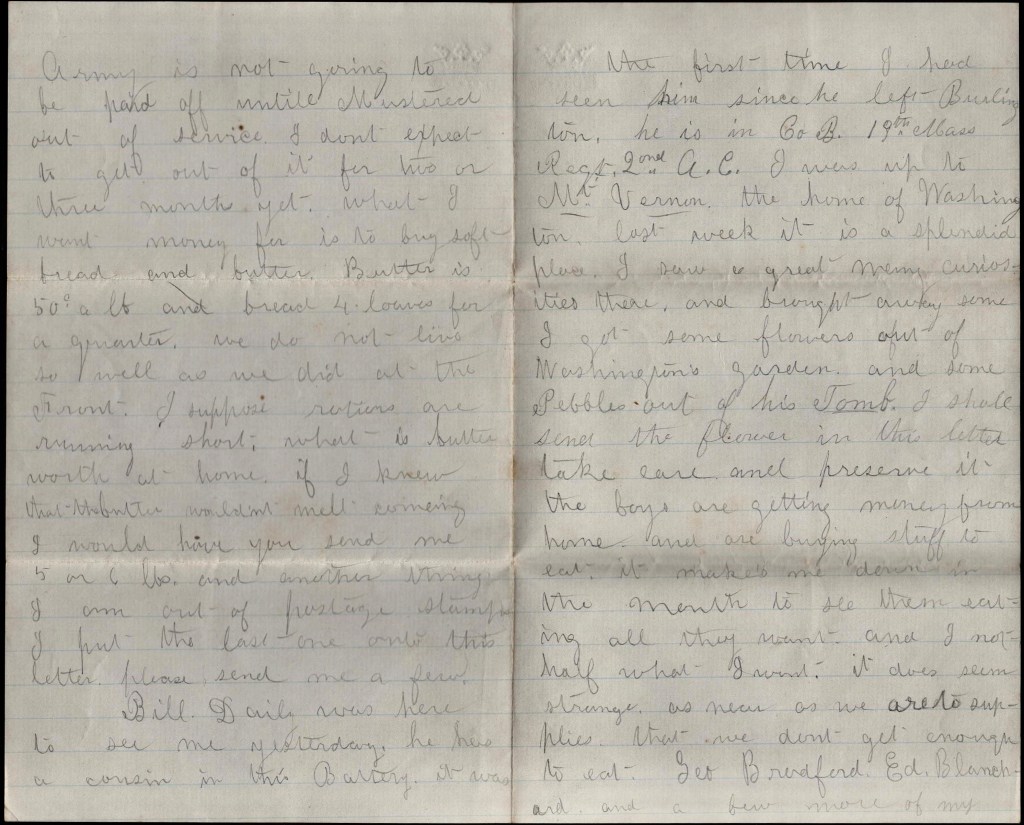

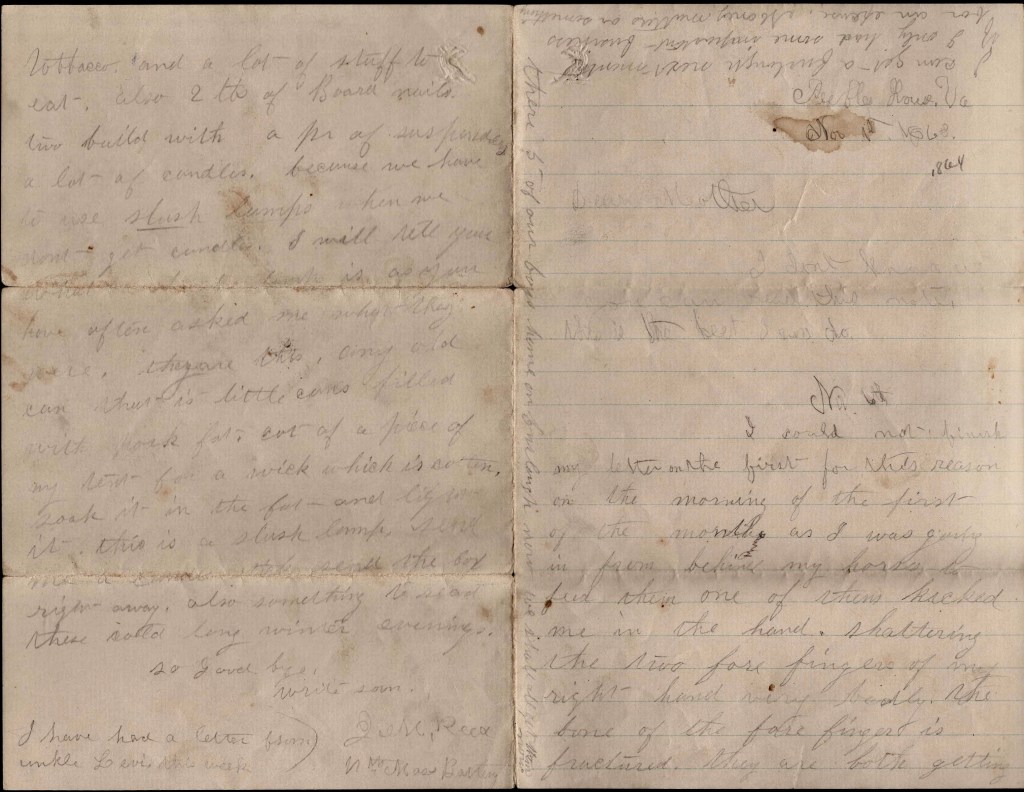

Letter 1

Camp Barry

March 20th, 1864

Dear Parents,

I received my box last Tuesday the 15th and since then I have received a letter from you. The eatables that you sent me are all demolished. They went very good. I gave a pie to the Captain. He thanked me very kindly for it. He said it was very nice and can back it up. They were nice—too nice to last. The other things suit me well. I have got a solid 12 lb. shot to send home as soon as I get some money. Also a piece of a spherical case shot.

We are situated on ground where the rebels have been and probably these were fired by them. Every thing that I got in the Box was very good except the tobacco—that is very poor. I wish father would get me some plug tobacco. That was what I wanted before; only it was cut up fine. If I was paid off, I would not ask you to get it, but I am not, and I don’t know when I shall. We have not got our Battery yet and they say we shall not get it until July. If we don’t, we will have to stay here a good while. We all want to go to the front as soon as possible where we shall live in tents and be more healthy. I was unwell for a few days, but nothing serious. I’m well now and a growing fat. I have got [ac]climated now and can guard myself from disease. I don’t want you to think I am not on good terms with George for we are just as fast as we ever were and are going to be. Don’t you feel alarmed about us. We are all right; both of us are well.

You wanted to know if I hadn’t rather sleep on a good soft feather bed than a soft pine board. A good feather bed would go good, that is a fact, but when you know you can’t have it, you must not think of it. I have got so I sleep just as sound on a board as I did when I was at home. I had rather be here than at home. It is much pleasanter. We have good times all the time. I would not give a cent to be in Charlestown. It is such a lonesome, dead place—only to see my folks and friends. I am not homesick at all. [I] like [it] first rate. Tell Abby I would like to write to her separately but I have so many letters to write, I can’t half write what I want to. I have got 8 letters to answer now. I must close. Love to all. From your son, –J. M. Reed

Letter 2

Battlefield ten miles from Ellson Green and fifteen from Richmond. We are beyond the Green. 1

May 31st. 1864

Amidst the flying of shells and the whizzing of bullets, I seat myself under a tree to write to you. Mother, I should really like to be at home tonight to supper—to get some hot biscuits and butter, and a cup of tea. Mother, how would you like to be a soldier without hardly anything to eat as I am? All I had yesterday was one “Hard-tack,” one spoonful of coffee, and one of sugar. Today I have neither. For a fortnight we have been drawing quarter rations but now we don’t get that. The reason is we are so far from our base of supply. Tomorrow the supply train will reach here I hope. We are agoing to draw whiskey rations—a gill a day. It makes the men hold out longer for we are so hard up. We are in good spirits. I have thought myself—although I never use the stuff—that a little whiskey would do me good, when we have been marching all day and night, no water to drink. I tell you, it makes a fellow think of home.

We have got so that we live cheap. I find no fault as long as we are so near Richmond and gaining ground every day. Last night our folks found the Rebs building breastworks. They waited till they had got it most finished and were putting their men behind them, when our boys charged on them and took it and hold it now. What an aggravation it must be for Rebs to work so hard for Feds.

We haven’t lost a man in our Battery but have had a few horses killed. One shell killed two. Tell Abby to tell Charley Blanchard that his brother was well the last time I saw him which was on the twelfth. Frank Knowles is safe and well—so be I.

Mother, you must not be discouraged if you do not get a letter for some time. I think it a blessing to get a chance to write. I would write every day if the mail could be sent but it is once in a great while that we get a mail or are allowed to send one. It makes me feel very bad to have you write [and ask] why I don’t let you know where I am and why I don’t write. I do the best I can to get you a letter. You must write me two letters a week certain and send lot of papers—daily papers preferred—and when the campaign is over and we get to camp, I will send for a box of eatables and see if I can’t have something to eat once, something in the shape of pies and cake, fried pies and doughnuts. I want you to have a lot of preserves made up this season so that I can have some when I send for it. I received that box all right. I bought me a rubber coat in Washington before we left.

Now Mother, write real often and let me know how the babies are getting along. Write often. Tell my friends to write. I shall write as often as I can. We are going to take Richmond. We expect to be at home next spring. Direct to J. N. Reed, 11th Massachusetts Battery, 2nd Division, 9th Corps. Washington D. C.

1 I have not been able to pinpoint this position but assume it was at or near Totopotomy Creek in which the 11th Massachusetts Battery played a part in the battle there on 29-31 May 1864.

Letter 3

At the siege of Petersburg

July 9, 1864

Dear parents,

I received a letter from you last night dated the 3rd stating that you were glad that I was in the rear. For my part, I had rather be up front. I feel more at home. But as it is not my place to be there, I shall do my duty as well as I can at the rear where I am doing duty as driver. Why don’t you keep drumming me about my money. What will come next. I don’t know. But every letter I get worrying about something. It makes me feel discouraged. I had as just as leave throw my life away here at the front than to be so discomforted. You cannot imagine one quarter wat a soldier has to suffer during a campaign—especially one like this. The privations, the hard marching, and the danger of his life is nought to make one feel down sometimes without having anything discouraging from home. You ought to cheer up the spirit of a soldier. I have never pitied anyone so much as I have the soldier.

Mr. Briggs, if he has been in the army, he has not seen any more of it than I have. I have seen very little gambling since I have been intimate that I have gambled my money away. It [rest of letter missing]

P. S. You can send me a dollar or two if you feel like it. — J. M. Reed

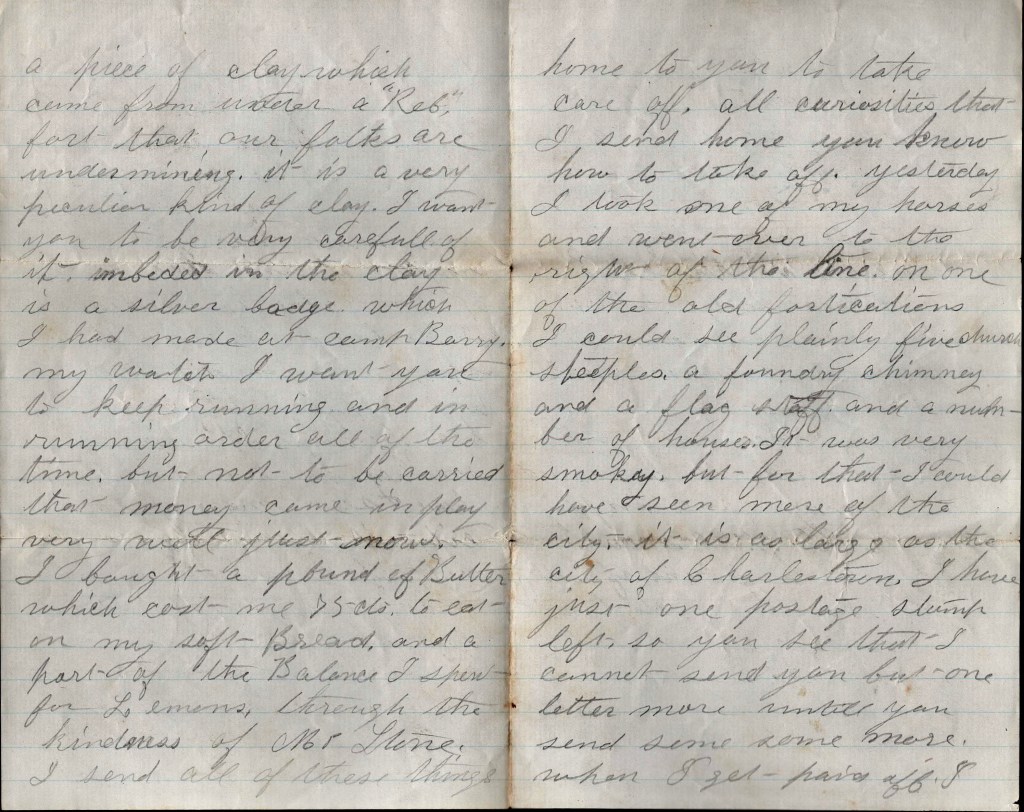

Letter 4

In front of Petersburg

July 22, 1864

Dear Parents,

I received two letters from you last night with money, ginger, and mustard in them. They are all right. The rhubarb has not come yet. What is the reason? Did you put it in a letter or in the papers? I should like it very much. Mr. Stone of Charlestown, the policeman there, he is after his son who is very sick. This letter I send by him. Also my watch and a piece of clay which came from under a “Reb” fort that our folks are undermining. It is a very peculiar kind of clay. I want you to be very careful of it. Embedded in the clay is a silver badge which I had made at Camp Barry. My watch I want you to keep running and in running order all of the time, but not to be carried. That money came in play very well just now. I bought a pound of butter which cost 75 cts. to eat on my soft bread, and a part of the balance I spent for lemons. Through the kindness of Mr. Stone I send all of these things home to you to take care off. All curiosities that I send home, you know how to take [care] of.

Yesterday I took one of my horses and went over to the right of the line. On one of the old fortifications I could see plainly five church steeples, a foundry chimney, and a flag staff and a number of houses. It was very smoky. But for that, I could have seen more of the city [of Petersburg]. It is as large as the city of Charlestown. I have just one postage stamp left, so you see that I cannot send you but one letter more until you send some more. When I get paid off, I will not send home for anything. I shall send my money all home for you to take care of. Have it put to interest if you can. I kept my money the last time I was paid off and most of the boys sent theirs home but were sorry for it, for they have needed it. But now I am going to send mine home and the most of the boys are going to keep theirs for themselves. I shall keep a little by me to get stuff that I cannot do without out. I am well. So are the rest of the boys. I cannot write anymore now so goodbye. From your son, — J. M. Reed

You will find a piece from our Battery in Sunday Herald of the 17th of July.

P. S. We have excellent water here to drink—the clearest I think I ever drank, cool and nice. Also all we want to eat. — J. M. R.

Letter 5

Near Petersburg

July 24, 1864

Dear Parents,

I received the paper with the rhubarb in it, but it was too late. I am all well of the jaundice and partly of the diarrhea. However, it will come in play sometime.

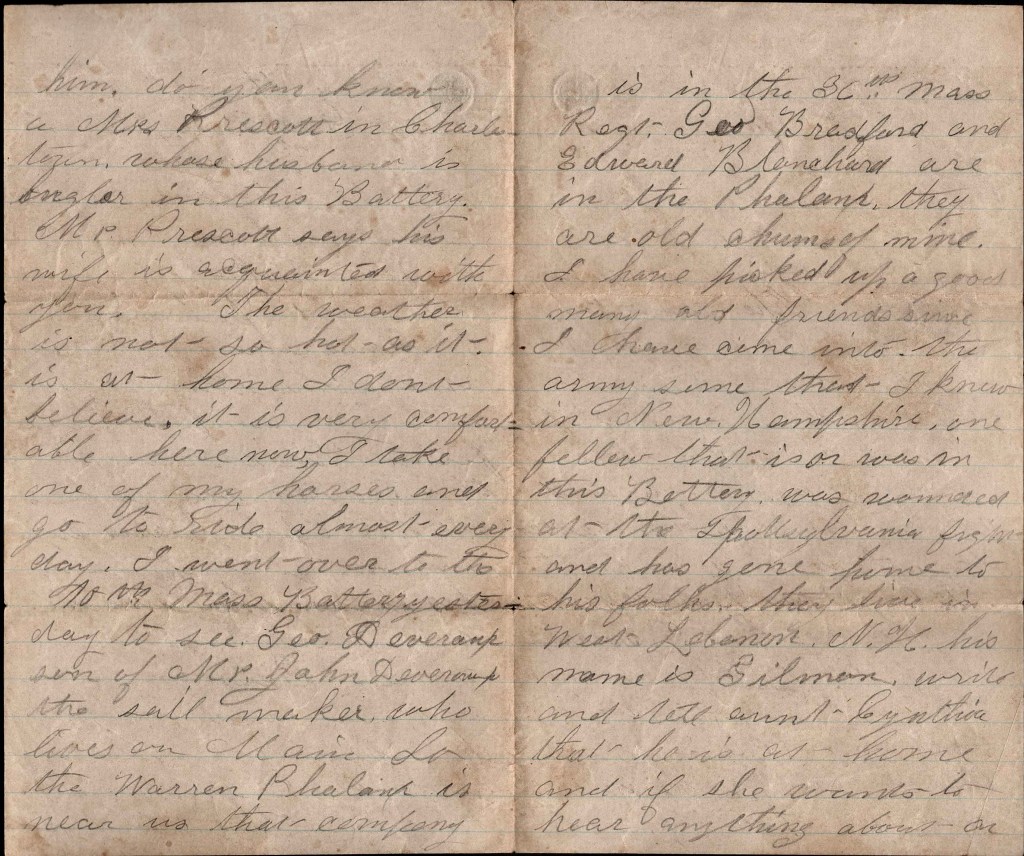

Mr. Stone is on his way home with [his] son. I wish I was in his place, don’t you? Only I should not like to be as sick as he has been. I have sent home my watch by him. Do you know a Mrs. Prescott in Charlestown whose husband is bugler in this Battery? Mr Prescott says his wife is acquainted with you.

The weather is not so hot as it is at home, I don’t believe. It is very comfortable here now. I take one of my horses and go to ride almost every day. I went over to the 10th Mass Battery yesterday to see George Deveraux, son of Mr. John Deveraux, the sail maker, who lives on Main Street. The Warren Phalanx is near us. That company is in the 36th Mass. Regiment. George Bradford and Edward Blanchard are in the Phalanx. They are old chums of mine. I have picked up a good many old friends since I have come into the army—some that I knew in New Hampshire. One fellow that is—or was—in this Battery was wounded at the Spottsylvania fight and has gone home to his folks. They live in West Lebanon, N. H. His name is Gilman. Write and tell Aunt Cynthia that he is at home and if she wants to hear anything about the engagements we have been in, he will tell her. I presume, if he is able, he can tell them about the marches we have had until he was wounded. Since then he cannot tell anything about the Battery.

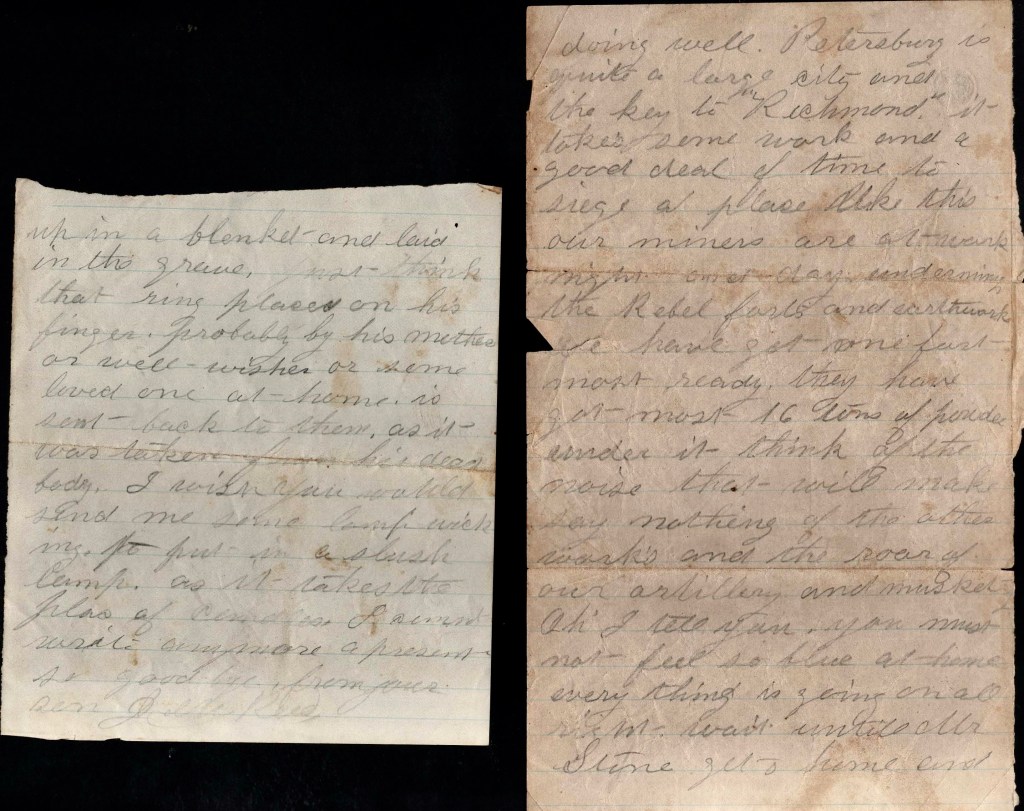

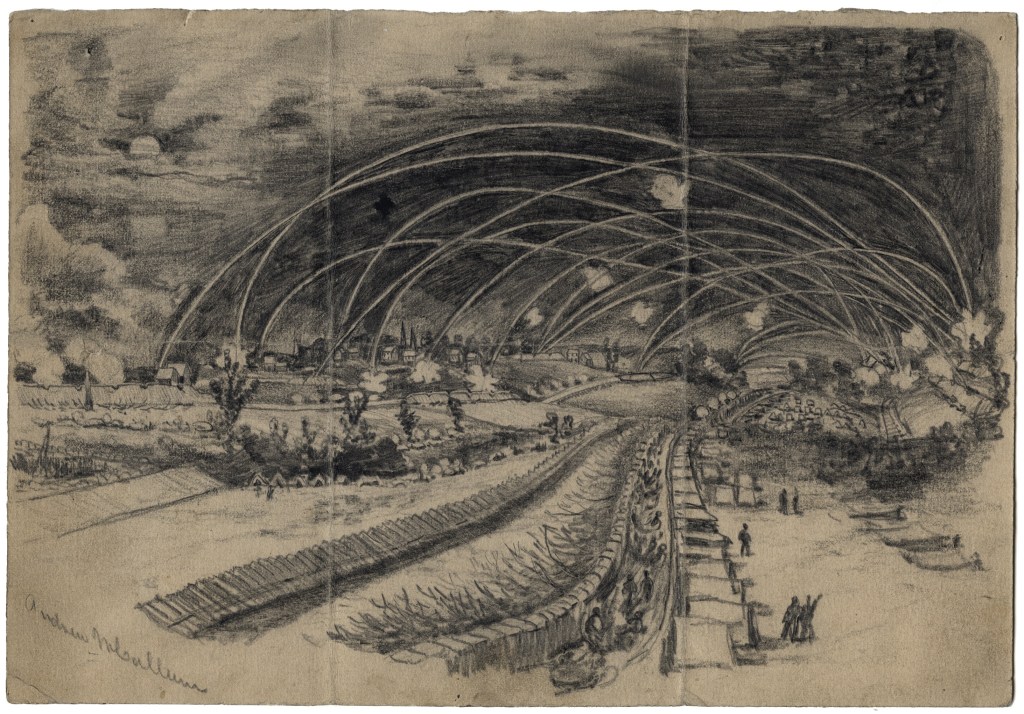

I want you to send me a pack of cards in some papers. Pack half a pack in one bundle of papers and half in another. Don’t think I want them to gamble with. I want them to pass the time away, for we have nothing to do. We stay here in the same old spot. I suppose you think that the army is not doing anything. I think we are doing well. Petersburg is quite a large city and the key to “Richmond.” It takes some work and a good deal of time to siege a place like this. Our miners are at work night and day undermining the Rebel forts and earthworks. We have got one fort most ready. They have got most 16 tons of powder under it. Think of the noise it will make, say nothing of the other works and the roar of our artillery and muskets.

Oh, I tell you, you must not feel so blue at home. Everything is going on all right. Wait until Mr. Stone gets home and he will tell you what he thinks about it. He said here that if the folks at the North knew what the army was doing, they would not complain about Grant and the army laying still.

As I came down from the front last night, I stopped to see a fellow soldier buried. He was brought to the edge of the hole on a stretcher and on removing the blanket from his face, I saw that he was shot in the head. And when he was removed from the stretcher, it was covered with blood and a part of his brains. They took a ring off of his finger and laid him in the grave. He was rolled up in a blanket and laid in the grave. Just think—that ring placed on his finger, probably by his mother or well wishers or some loved one at home, is sent back to them as it was taken from his dead body. I wish you would send me some lamp wicking to put in a slush lamp as it takes the place of candles. I cannot write anymore at present so good bye from your son. — J. M. Reed

P. S. Write as often as you can. Love to all, tell somebody to write. I am going to write uncle Frank in a day or two. Yours in haste — J. M. Reed

This is our Corps Badge. I wish you would get a lot of these envelopes and have then stamped like this one.

The Battle of the Crater took place just a week or so after Joseph wrote the last letter. He does not have an account of the battle but another member of his Battery named William Hazen Flanders described it in a letter to his friend, Millie E. Stevens of Boston. The letter was posted on The Siege of Petersburg website. It was then (2014) in the possession of Gary Skinner. The relevant portion reads:

“….You remember I have written you from time to time of the mining operations part of the ninth corps under a large rebel fort. Last week the mining operations were finished, the powder was carried in (6 tons) on Thursday and Friday, and Saturday morning was fixed upon for an attack by our corps.

At 4:00 AM Saturday morning the fort was blown up, killing a large number of rebels, mostly South Carolina soldiers and dismantling their guns, throwing the dirt in all directions. I was up to the front and I will never forget what a noise the explosion made, this was the signal for artillery to open, and immediately our batteries on the line, and others “some 200 guns” opened a terrific fire on the rebels and kept up our fire about 4 hours. In the meantime our infantry charged on the rebel works and took the 1st line, then charged on the 2nd . When the 4th division of our corps (colored) were brought into position, everything indicated success for us, the rebels were leaving their guns and works, but when they saw the colored troops they charged on them, driving them in disorder back to our works, and they rushing back so it tended to confuse our white soldiers, and no commanding officers to be found to rally them for the simple reason that they were in the rear drunk, incapable of doing anything. That our gallant boys were defeated with great loss in killed and wounded, besides losing several stands of colors, and we are now in the same position we were before the attack. It was an unfortunate affair, it being the first defeat we have experienced in the Army of the Potomac since the campaign opened. It was not the fault of our brave soldiers by no means, but can be summed up in 3 letters “rum was the cause of it.”

On Monday a flag of truce was sent out to bring off the wounded and bury the dead. I went out onto the late battlefield and truly it was a sad sight to view—one I shall never forget. Our wounded had been laying between the two lines for 48 hours in the hot sun, only 21 (one) alive for brought off the field and their wounds were alive with maggots. You could not distinguish a white man from a colored one, all turned black, &c.

I saw the rebel general Hill and other officers. Hill is a splendid looking man. It seemed odd to see our man and the Johnnies trading when only a short time before they were trying to kill each other. I conversed was several of them and they all said if the colored troops had been kept out of the fight, we would have gained the day, but when they saw them they were determined not to surrender to them, but if some of the Generals commanding certain divisions had been in their right mind as they should have been, no such disaster would have occurred to us. Our boys felt disheartened at first, but are ready to try again and I think we will not be so unlucky. I suppose the matter will be kept quiet as to the cause, but it will work out sooner or later by letters sent north from the soldiers. I trust the officers who are guilty will be punished as they deserve and receive the just merit due them for the conduct unbecoming in an officer and a gentleman.

General Burnside feels mortified at our defeat and I hear from good authority that several officers in the corps will be court martialed. I am happy to say although our batteries were under a severe fire from the rebel artillery and musketry, none of our boys were killed or wounded. Since I wrote to you though, we have had a 3 men wounded severely. Probably one of them will lose the use of his left arm. The battery is still in position on the skirmish line of having been there since July 5th….”

Letter 6

Jones House near Petersburg

October 1, 1864

I have received two letters from you lately and one with a receipt for the box. The box has not got along yet but expect it as soon as the battle is over. We are having a big battle [see Battle of Vaughan Road]. I think that the Rebs have lost all this time. We are on the move again. There is a big battle going on now. Sheridan and Sherman are cooperating with this army. We have nearly surrounded Lee. Sherman is at Lynchburg and Sheridan is within two miles of Richmond. His pickets [are] within one mile and a half from the city. These are all rumors and we believe it.

Our pieces are in position in Fort Howard on the front line and our caissons were ordered to the rear about three miles and as I am a driver on one of them, I have to be at the rear. We were ordered to have four days rarions in our knapsacks but we did not get but about two and today is the third day and I feel a little kind of hungry and wish I had my box. Why didn’t you send a list of the articles that you sent in the box. I do not expect the box until this battle is over.

We have whipped them so far this battle which has been going on two days. I cannot write any more now.

I want another box about Thanksgiving time with a lot of good eatables—turkey, pies, cake, preserves. What did you send this time? I am well. — J. M. Reed

Don’t feel worried about me. I am all right.

Letter 7

Peeble’s House, Va.

Oct. 25, 1864

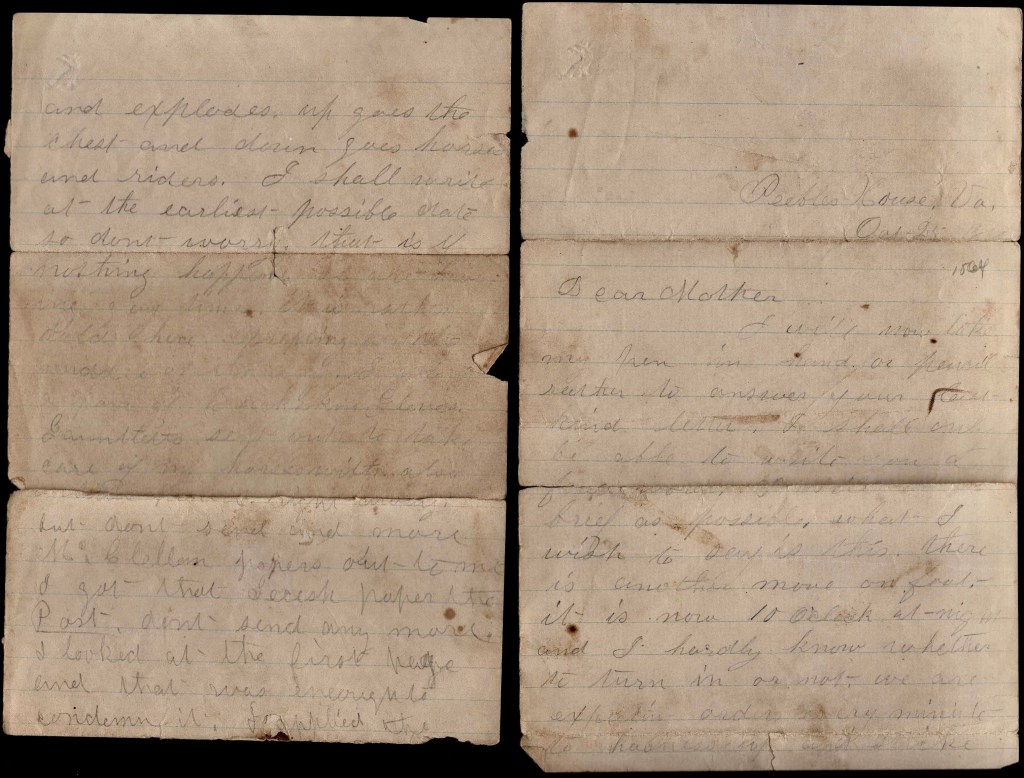

Dear Mother,

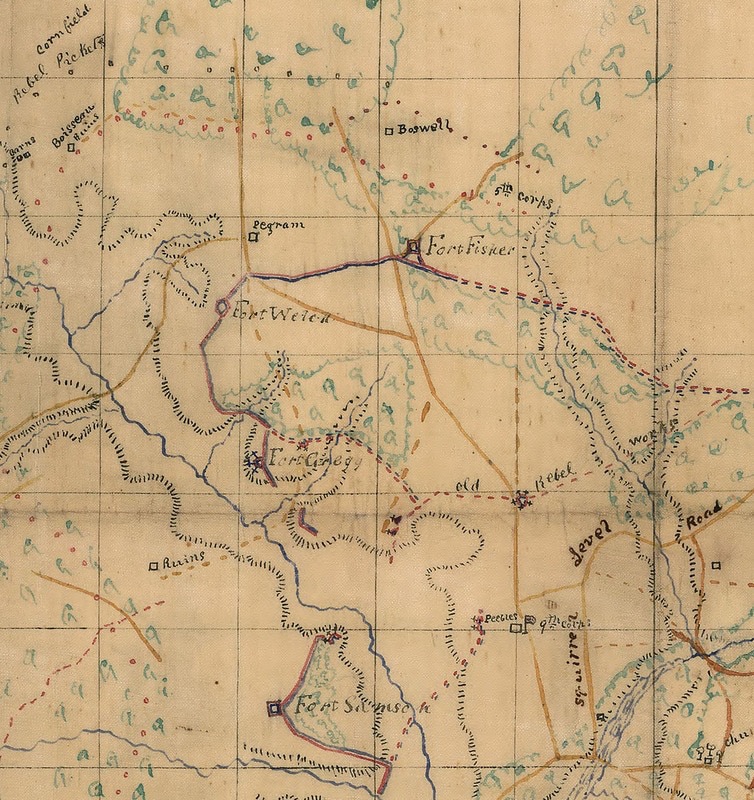

I will now take my pen in hand—or pencil rather—to answer your last kind letter. I shall only be able to write you a few words. I will be as brief as possible. What I wish to say is that there is another move on foot. It is now 10 o’clock at night and I hardly know whether to turn in or not. We are expecting orders every minute to harness up and strike tents. Hark! I hear the tramp of a horse in front of Headquarters. It is an orderly with a furlough for one of the boys. Thank the Lord it is not an order to harness up. We have got orders to be ready at a moments notice and so we expect it every moment. We are going to push our lines to the Appomattox River across the Southside Railroad.

I am nearer danger now that I was a short time ago. I am now driver on the piece—the pole team. Before this I was driver on the caisson in the rear. If a shell strikes the limber chest and explodes, up goes the chest and down goes horses and riders. I shall write at the earliest possible date, so don’t worry—that is, if nothing happens. We are having a gay time. It is rather cold here excepting in the middle of the day. I want a pair of buckskin gloves [with] gauntlets sent out to take care of my horses with. Also [ ] right away, but don’t send anymore McClellan papers out to me. I got that secesh paper—the Post. Don’t send any more. I looked at the first page and that was enough to condemn it. I applied the torch to destroy it. Burn ye traitor’s editorial.

There is going to be a heavy battle fought in a few days and I hope I shall come out safe as I expect to have a hand at it. Some of the boys have got furloughs for not over 15 days. I shall not apply for one until winter, say about February, so to be at home on my birthday when I shall be of age. I shall want some preparations made to receive me and my friends if I do come. I don’t wish to come home yet awhile—not because I don’t want to see you all because I do. But it is because I am contented where [ ]. — J. M. R.

Letter 8

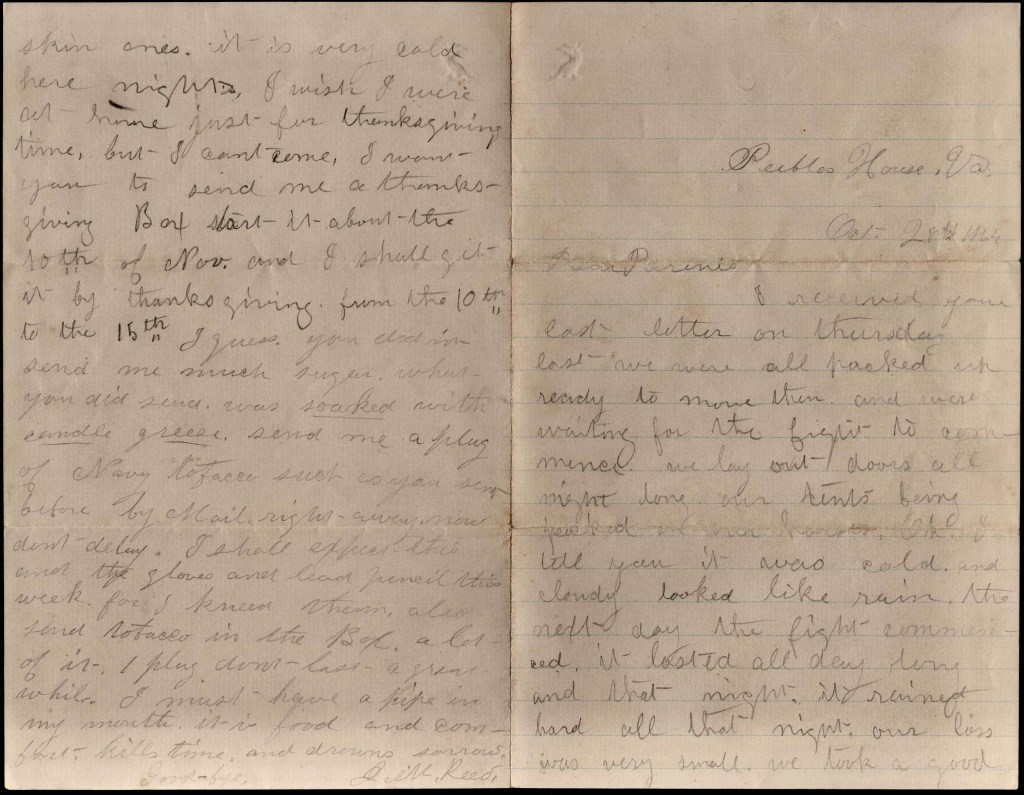

Peeble’s House, Va.

Oct. 28th 1864

Dear Parents,

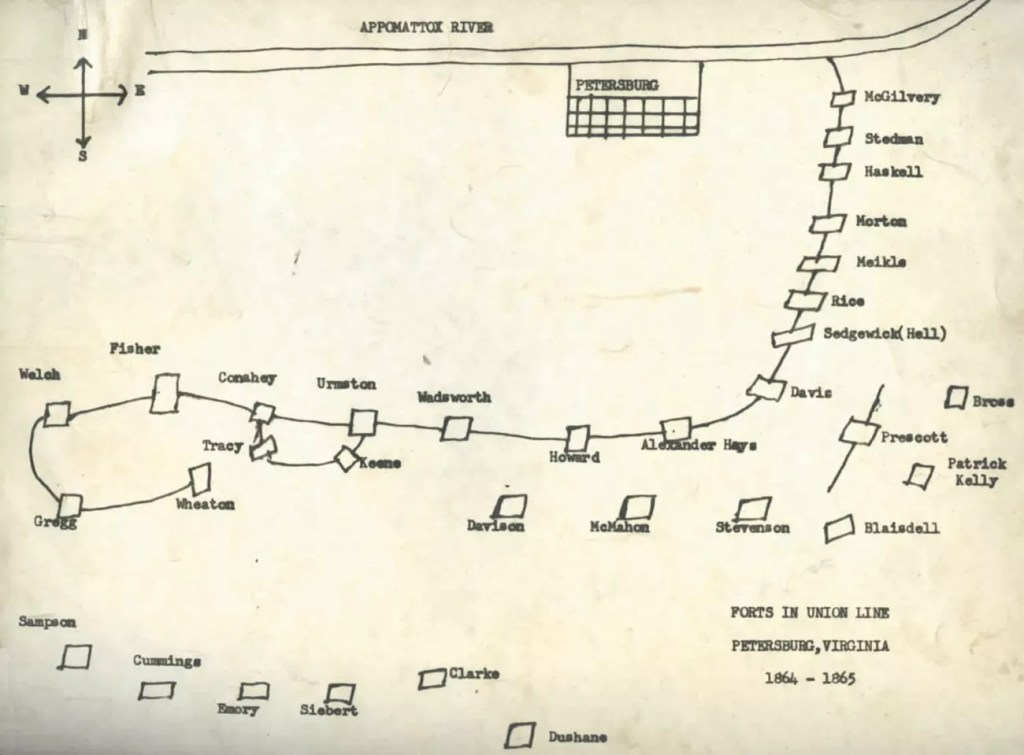

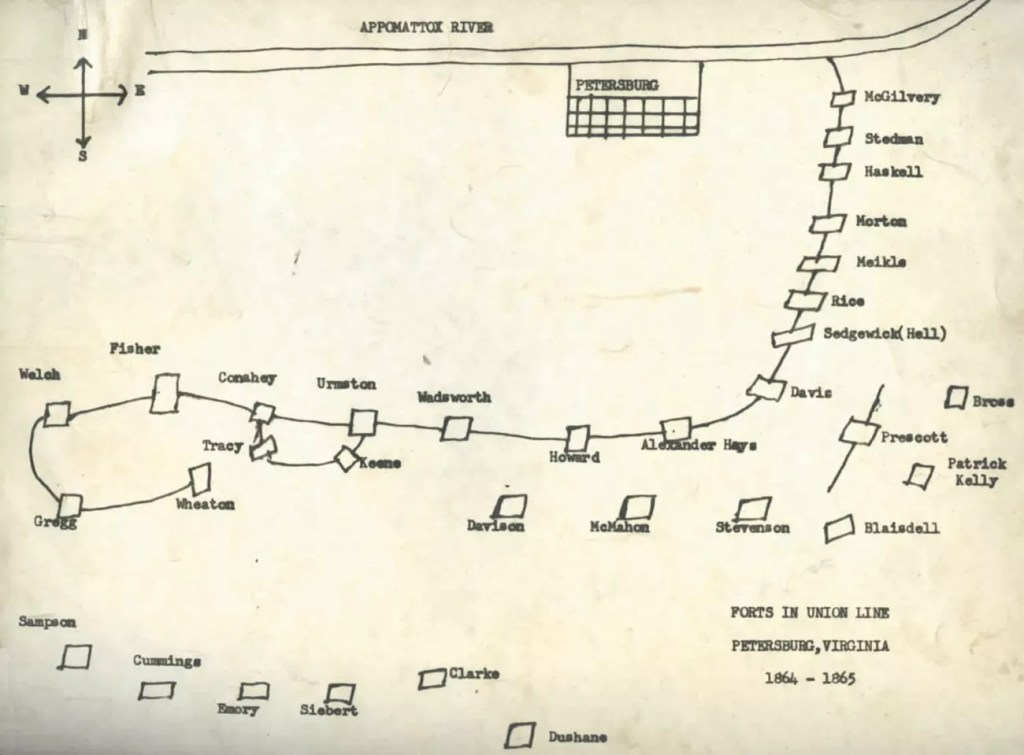

I received your last letter on Thursday last. We were all packed up ready to move then and were waiting for the fight to commence. We lay outdoors all night long, our tents being packed on our horses. Oh, I tell you it was cold and cloudy—looked like rain. The next day the fight commenced. It lasted all day long and that night. Our loss was very small. We took a good many prisoners. We advanced our line about three miles. Our Battery was not engaged in this raid. One section (2 guns) of our Battery forms part of the garrison of Fort Sampson and the other two sections (4 guns) is the entire garrison of Fort Cummings. These forts are on the front line.

We were all ready to move out of our old camp by we didn’t have to move. What we have gained in this movement, I am not able to say as I have not learned the particulars. The heaviest fighting was way down on the right where Butler is and this move on the left was merely a feint to draw the Rebs from the right—to give Butler a chance to do something. I think that is what this move was for, for we heard heavy guns and [could] see the flashes of the guns in the night. 1

The line of works that we are on is about 30 miles long. Butler is on the right and we on the left, so you can imagine what a distance cannonading can be heard and see how far apart we are, and what a force of troops we have got to take Richmond with.

I want you to send me out a new portfolio, a lead pencil, and a pair of gloves—buckskin ones. It is very cold here nights. I wish I were at home just for Thanksgiving time, but I cannot come. I want you to send me a Thanksgiving box. Start it about the 10th of November and I shall get it by Thanksgiving; from the 10th to the 15th. I guess you didn’t send me much sugar. What you did send was soaked with candle grease. Send me a plug of navy tobacco such as you sent before by mail right away. Now don’t delay. I shall expect this and the gloves and lead pencil this week for I need them. Also send tobacco in the box—a lot of it. One plug don’t last a great while. I must have a pipe in my mouth. It is food and comfort. Kills time and drowns sorrow. Goodbye. — J. M. Reed

1 The Union offensive described in this letter refers to Grant’s Sixth Offensive which was an effort to capture the South Side Railroad, cutting off a major supply line to the besieged cities of Petersburg and Richmond. If successful, it would have been a major Union victory prior to the Presidential election of 1864. A two pronged attack was launched, with Butler’s troops attacking the Richmond defenses north of the James River while elements of the 2nd, 5th, and 9th Corps skirted the rebel defenses southwest of Petersburg to get at the South Side Railroad. Fort Cummings, where 4 guns of the 11th Massachusetts Battery were planted, was the point in the Union defensive line from which the 5th and 9th Corps launched their marches. Joseph’s interpretation of events was incorrect; the attack on the right by Butler was intended to hold Confederate troops between Richmond and Petersburg into position while the main objective was to capture the South Ride Railroad on the left.

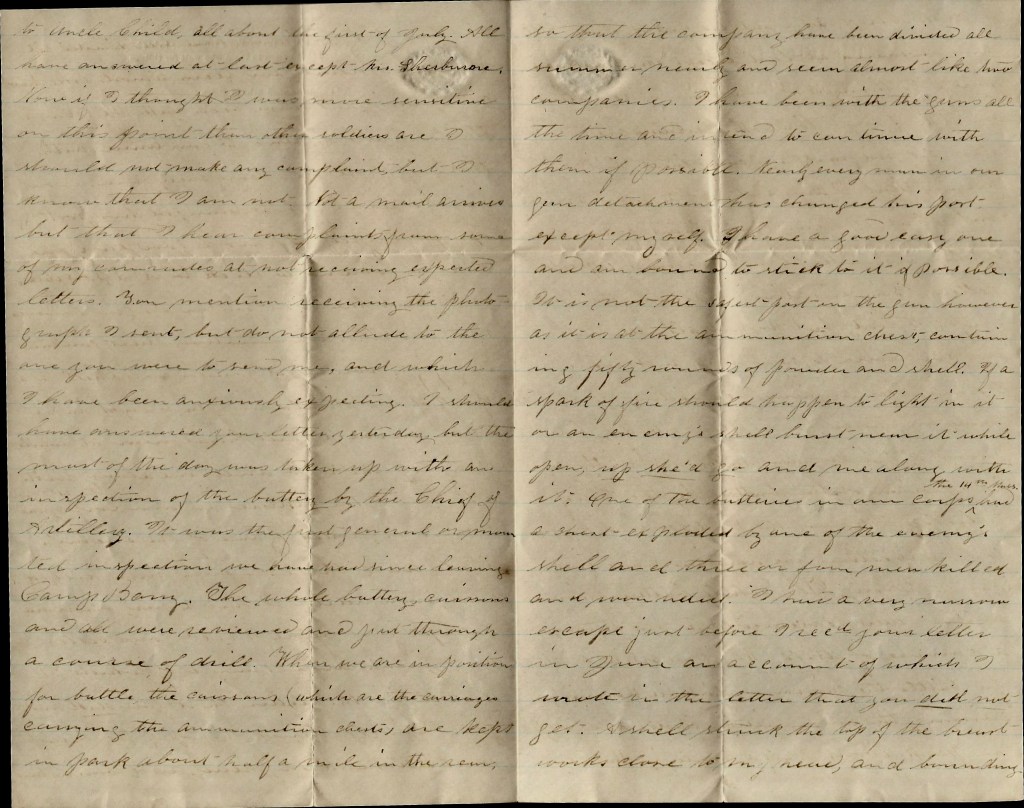

Letter 9

Peeble’s House, Virginia

November 1, 1864

Dear Mother,

I don’t know if you can read this note. This is the best I can do.

Nov. 6th. I could not finish my letter on the first for this reason. On the morning of the first of the month, as I was going in from behind my horses to feed them, one of them kicked me in the hand, shattering the forefinger of my right hand very badly. The bone of the forefinger is fractured. They are both getting along nicely. I am just able to write now with my thumb and little finger. You see by the writing of the first part of the letter that it is written very badly. It was written with the left hand. The doctor says if I catch cold in my fingers, I may have to have them cut off. I hope I shant.

Everything looks lovely and pleasant here. We got orders the day I got hurt to go into Winter Quarters and today I have got a good log hut about 5 feet wide and 8 feet long with a bunk for two in it, a fireplace, mantle piece, bench and table. Everything’s gay. We are right in a pine grove under a hill. Oh, it is a pleasant place. My hut was not all of my own building. All that I could do was to do all that I could do with one hand, such as lugging logs on my shoulder and helping. My tent mates did the rest. It is a log cabin built of logs and plastered with mud outside and in. And to make it more pleasant, I want you to send me out a nice box just as quick as you can for Thanksgiving. You cannot start it any too quickly. If you send it as soon as you get this letter, I shant get it by thanksgiving time. I supposed you would have started one before now. Send a lot of tobacco and a lot of stuff to eat. Also 2 lb. of board nails to build with, a pair of suspenders, a lot of candles because we have to use slush lamps 1 when we don’t get candles. I will tell you what a slush lamp is as you have often asked what they were. They are this—an old can that is little, filled with pork fat and a piece of my tent for a wick which is cotton, soak it in the fat, and light it. This is a slush lamp. Send me a candle stick. Send the box right away. Also something to read these long winter evenings. So goodbye. Write soon. — J. M. Reece, 11th Massachusetts Battery

I have had a letter from Uncle Levi this week. I can get a furlough next month if I only had some important business for an excuse. Money matters or something. There are 5 of our boys home on furlough now. We shall all get them now.

1 “Slush lamps” were made from cooking grease and a cloth wick when candles were scarce.

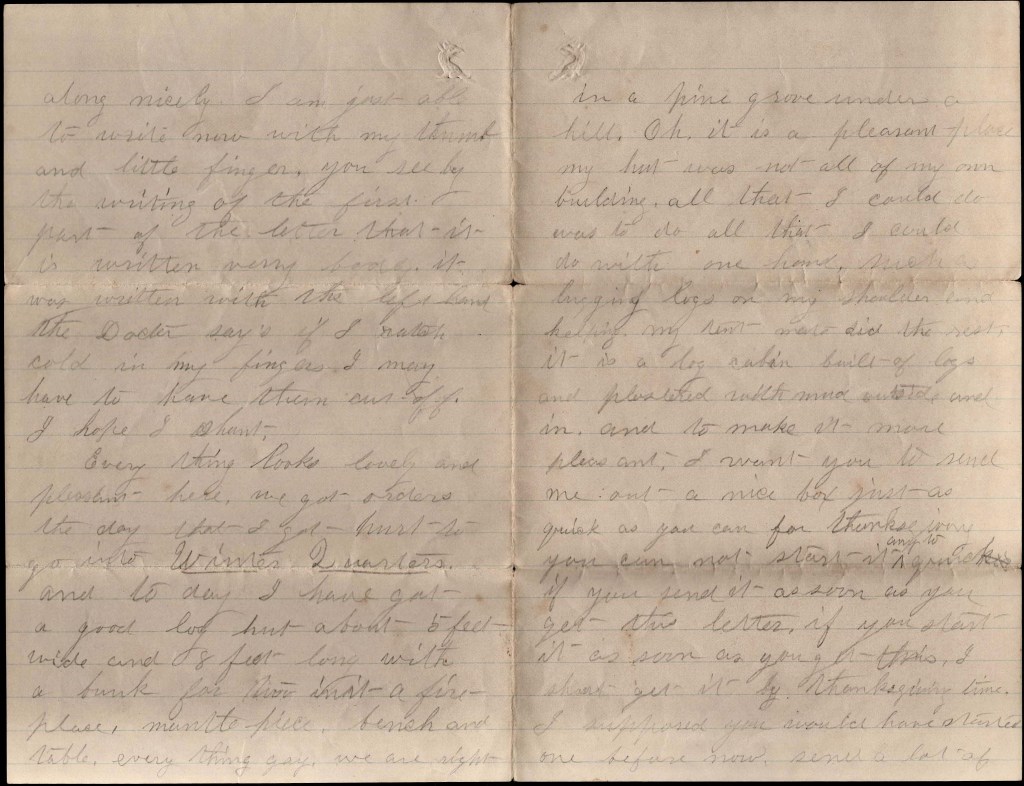

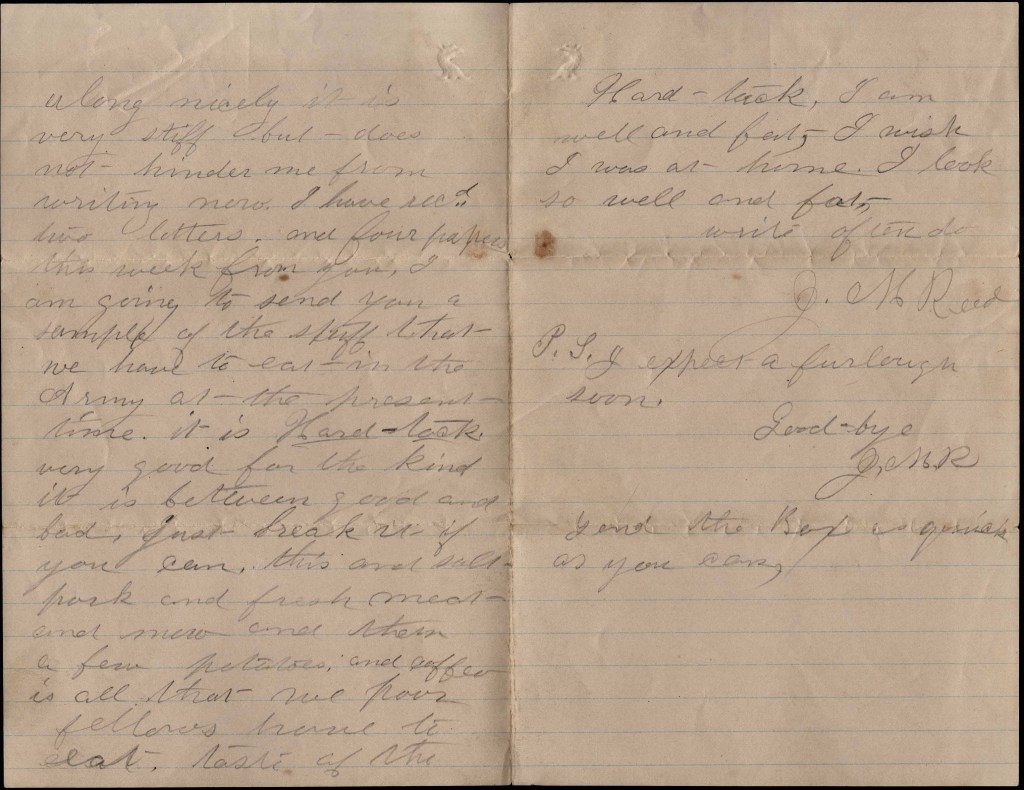

Letter 10

Peebles Farm, Virginia

November 12th 1864

Dear Mother,

It is Saturday and I am on guard tonight so I thought I would write to you. You needn’t feel at all alarmed about my position for as long as our pieces stay in position, I shall be in the rear with my horses. I have got a better position than I had before. My finger is getting along nicely. It is very stiff but does not hinder me from writing now.

I have received two letters and four papers this week from you. I am going to send you a sample of the stuff that we have to eat in the army at the present time. It is Hard-tack—very good for the kind. It is between good and bad. Just break it, if you can. This and salt pork and fresh meat and m___ and then a few potatoes and coffee is all that we poor fellows have to eat. Taste of the hard-tack. I am well and fat. I wish I was at home. I look so well and fat. Write often do.

—J. M. Reed

P.S. I expect a furlough soon. Goodbye, J.M.R.

Send the Box as quickly as you can.

Letter 11

Winter Quarters, Peebles Farm, Va.

November 20, 1864

Dear Mother,

I received your last letter with recipe of box therein. Also a list of costs. I would like to know if the articles—pies, h___, molasses, salt, cranberry sauce, apples—I hope you bought on purpose to send me. If so, I will pay for them. If you didn’t, I don’t see why I should pay for them. But if you say I shall pay for them, I will do so. I shall get the box this week—just in time for Thanksgiving. I am very sorry you did not send me more tobacco. That will go but very little way. However, when I get paid off, I shall send home $5 to be spent for tobacco—all of it. That clay pipe you sent out to me I have smoked so much in it that it is as black as a coal.

Now there is an article that I want right away. I want it now. It is my watch. I want father to take it over to the Waltham Watch C0. on Washington St. and inquire for Charles Fuller, bookkeeper, a friend of mine, and tell him I want my watch put in good running order, perhaps cleaned, and a good key, and as pretty a steel chain as can be got. I guess Abby can get the chain. I don’t want one with a snap on the end to hook on to the watch, but a screw loop. I want it packed very nicely in cotton batten and put into a little paste board box and sent by Adams Express Co. Abby, I want you to get me a fancy steel chain with a bar on one end to put in the button hole of my vest and screw loop on the other end. Don’t get a big link chain.

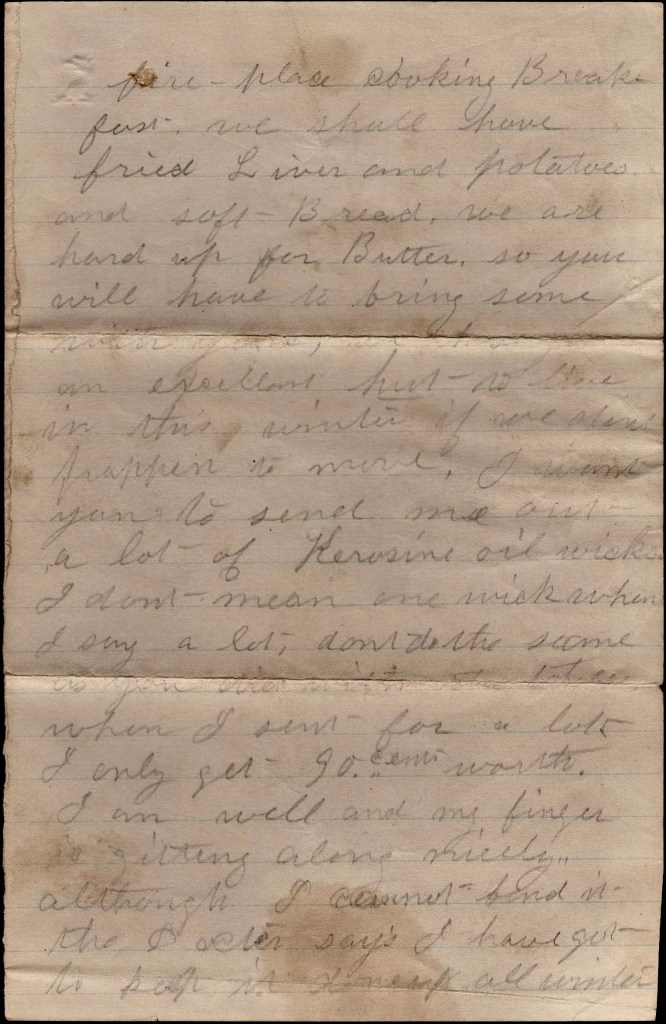

Now send the watch as quick as you can, and I will pay all damages when I get paid off. Also send my suspenders and a small rubber course pocket comb and a wallet by mail at different times. Now don’t forget these things, will you. I am all out of money at the present time. But for my tent mate, or my “old woman” wife as I call him, I should go hungry. He has got some money and as it is natural to soldiers not to go hungry when they can get anything to eat, we buy potatoes of the sutler at 10 cents a pound, and a whole liver at a time of the Brigade butcher. Now tomorrow morning, if you will call into my cabin, No. 14 Jones Row, at four o’clock, you will see my old woman in front of the fireplace cooking breakfast. We shall have fried liver and potatoes and soft bread. We are hard up for butter so you will have to bring some with you. We have an excellent hut to live in this winter if we don’t happen to move. I want you to send me out a lot of kerosine oil wicks [and] I don’t mean one wick when I say a lot. Don’t do the same as you did with the tobacco when I sent for a lot [and] I only got 90 cents worth.

I am well and my finger is getting along nicely although I cannot bend it. The doctor says I have got to keep it done up all winter. If I don’t and it froze, I shall lose my finger and perhaps my right arm. We have a doctor with our Battery now. I cannot write more now. Send that watch right away now as it is getting time to have a watch about me so when I go away, I shall know when to get back [and] to be on hand when the bugle blows. We are in camp now, you know, and have to have bugle calls. I will name some of them. Viz: reveille, stable call, feed call, water call, retreat—this retreat means police call, tattoo—when the sun’s down, retiring to rest, recalls from stable, taps in the far west, supper call.

Write soon, — J. M. Reed

Send the watch and pay the express on it. Be sure and have the value put down. Value $40 as that is what it is worth. It’s worth over 50 to me.

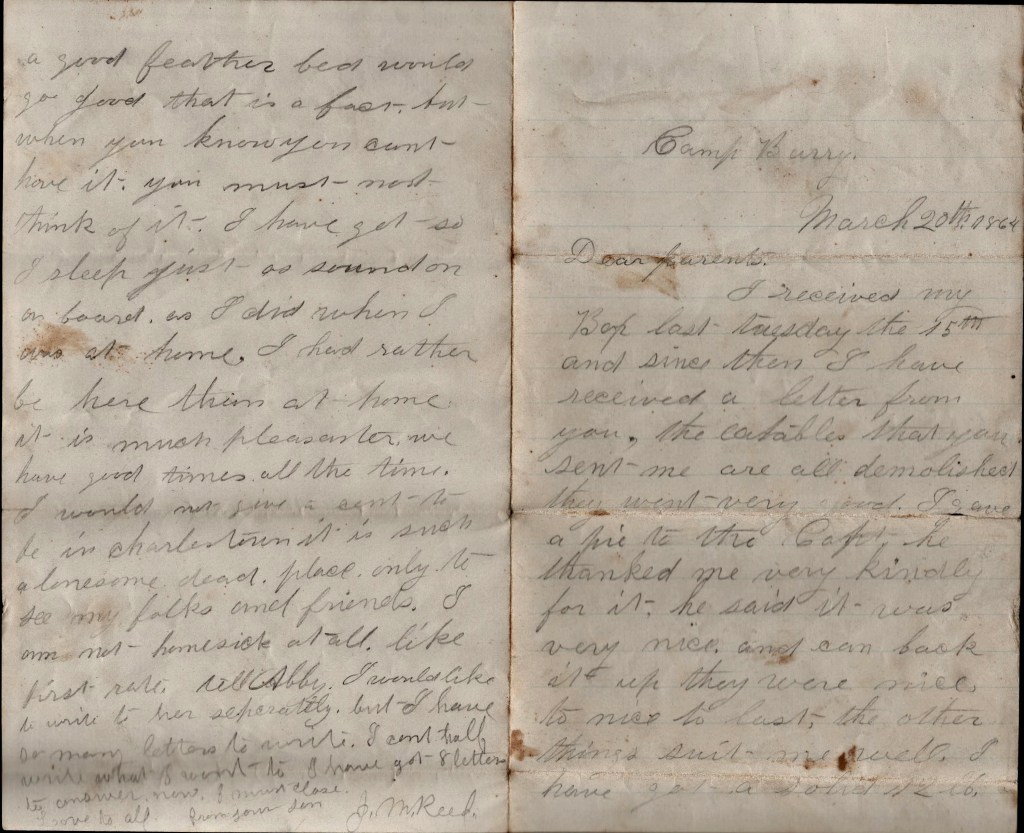

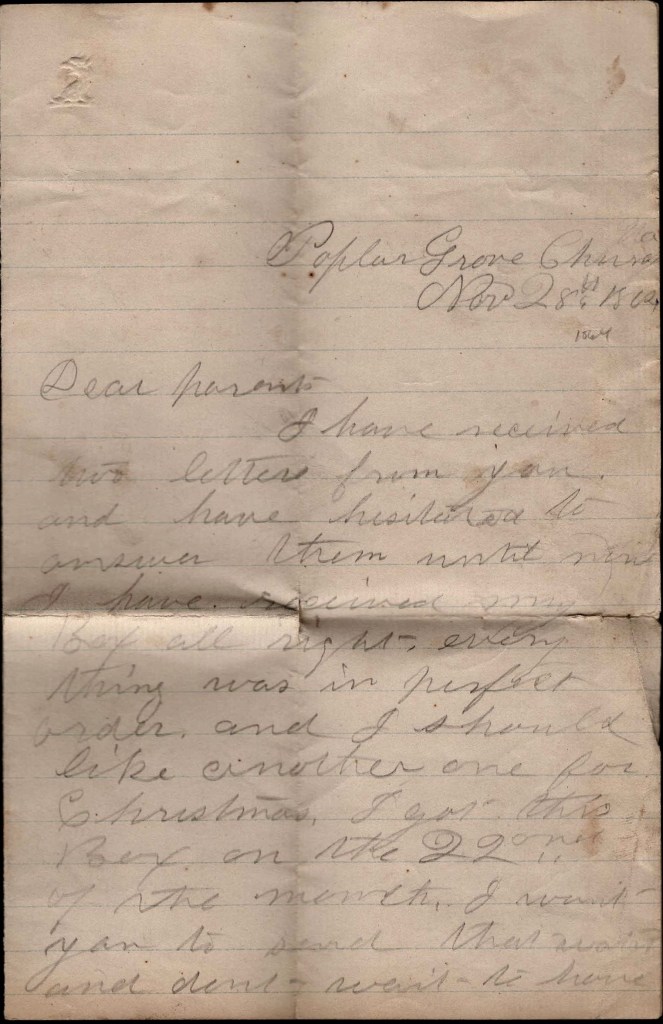

Letter 12

Popular Grove Church Va.

November 28th, 1864

Dear parents,

I have received two letters from you and have hesitated to answer them until now. I have received my box all right. Everything was in perfect order and I should like another one for Christmas. I got this box on the 22nd of the month. I want you to send that watch and don’t wait to have me send for it again as I need it very much.

I had a very good time Thanksgiving. Beans for breakfast, turkey for dinner, pie & cake, bread, butter, sauce for supper. Massachusetts soldiers did not get much of the stuff she sent out for Thanksgiving. I will tell you what her troops in this noble 11th Battery got. Viz: one lb. turkey, 2 apples, and half of a common size seed-cake to each man, and this the next day after Thanksgiving. The Old Bay State did well to send us the stuff. But the stuff was consumed mostly by officers, only giving the privates a very small share. Never mind; in two years more I hope to be out of this army. I am very well and living high all the time. I wish you could see me when I am eating my frugal meal. Ill bet you would laugh.

I am on guard tonight so I cannot write any more tonight. So I must bid you good bye hoping that you are all well. How are the babies? I will write more next time. So goodbye. — J. M. Reed

Letter 13

Breakers Ahead

Before Petersburg, Virginia

Near Birneys Station

December 4th 1864

Dear Pazents,

I received your kind letter last Thursday night. I am very sorry to say that we have left our good quarters on the extreme left and have marched below the city of Petersburg near Bermuda Hundred. We are right in sight of the city. It is a gay looking place. Oh, I tell you, they do throw the shells into our forts fearfully. I don’t know how soon I shall have to write you [of] the death of one of our numbers for we are in a very bad place. We are in Fort McGilvery on the extreme right of the Army of the Potomac. We have built us very comfortable quarters out of logs. We are not exactly in winter quarters [but] we were ordered to make ourselves as comfortable as possible, so we call it winter quarters. We are more comfortable than we were before. We are now 20 miles from where we were the left—where I wrote you last.

When I wrote you before, I sent for my watch and I never send and I never send for a thing without I want it. Now I want you to send that watch as soon as you get this letter. I don’t care if there is another campaign or not, I want the watch. Now you send it! If You don’t I shant write again. What do you suppose I sent for it for if I didn’t want it. I want you to send the watch as I directed you to and then I want you to send me out a Box for Christmas. And send me out two pairs under shirts and drawers and two pairs outside woolen shirts of the handsomest figure you can find in the market. Don’t make up any plain stuff now. Remember I want you to write me what they cost and I will send you the money as soon as I get paid off. Get some stout, fancy flannel—not very thick as the weather is moderate and I shall not need them thick. Also, send me the stuff I have sent for in previous letters. Read my letters more carefully and see what I write. Read them a second time if you cannot understand them the first. Don’t let me ask you to send my watch again, but send it this time and not delay. If you don’t I shall not write until you do send it. I want a comb and wallet and suspenders. Send box Christmas & New Years. 1

Write often, — Joseph M. Reed

P. S. My box came through all right. Not a thing was spoilt. Where is that box of books that somebody was going to send me? I wish the would send them now. Sed box of tobacco in my boxes.

1 It’s not often I feel compelled to share a personal observation, but I can’t help saying that this paragraph is perhaps the most rudely worded one among the thousands of soldier’s letters I’ve ever transcribed.

Letter 14

In front of Petersburg, [Va.]

December 14th 1864

Dear Mother,

I recieved about 10 days ago a splendid library from No 13 Cornhill, Boston, containing 26 very choice cloth bound books. They are all pious books. I tell you, it makes my cabin look gay. I have made a bookcase for them. There are 4 of us in the hut together. Our hut is built larger than the one we had up on the left. It is 12 x 8 feet, I think, with a splendid brick fireplace.

I will tell you what we had for supper tonight. It was fried liver, soft bread and butter, and coffee. Tomorrow evening we shall have hot biscuit and butter for tea. Please make a call in the afternoon and stop to supper. Bring you knitting work so to spend the evening by an old fashioned fireside. You would think you were in grandmother’s kitchen if you were in our hut. But don’t let me tantalize you with my story. I think I had rather sit by Grandmothers fireplace than this one. I will write more next time. I hope you have sent my watch. Love to all.

— J. M. R.

Letter 15

Near Fort Lyons

Alexandria, Virginia

May 26th 1865

Dear Mother,

I received your letter of the 24th inst. together with the pictures. The pictures were not taken very well. Do you think they were? How big and fleshy they were, I should not known them had I got home before she died.

How is times at home? The two dollars you said you sent me has not reached me yet. I wish you would send me 5 or 6 dollars for I need it very much and the army is not going to be paid off until mustered out of service. I don’t expect to get out of it for two or three months yet. What I want money for is to buy soft bread and butter. Butter is 50 cents a pound and bread, four loaves for a quarter. We do not live so well as we did at the front. I suppose rations are running short. What is butter worth at home? If I knew that the butter wouldn’t melt coming, I would have you send me 5 or 6 pounds. And another thing, I am out of postage stamps. I put the last one onto this letter. Please send me a few.

Bill Daily was here to see me yesterday. He has a cousin in this Battery. It was the first time I had seen him since he left Burlington. He is in Co. B, 19th Massachusetts Regt, 2nd Army Corps.

I was up to Mount Vernon, the home of Washington, last week. It is a splendid place. I saw a great may curiosities there and brought away some. I got some flowers out of Washington’s garden and some pebbles out of his tomb. I shall send the flower in this letter. Take care and preserve it.

The boys are getting money from home and are buying stuff to eat. It makes me down in the mouth to see them eating all they want and I not half what I want. It does seem strange, as near as we are to supplies, that we don’t get enough to eat. George Bradford, Ed Blanchard, and a few more of my old schoolmates will be at home soon. They are in the 36th Regiment. Please send a greenback as soon as you get this. In haste. I am well. — J. M. Reed