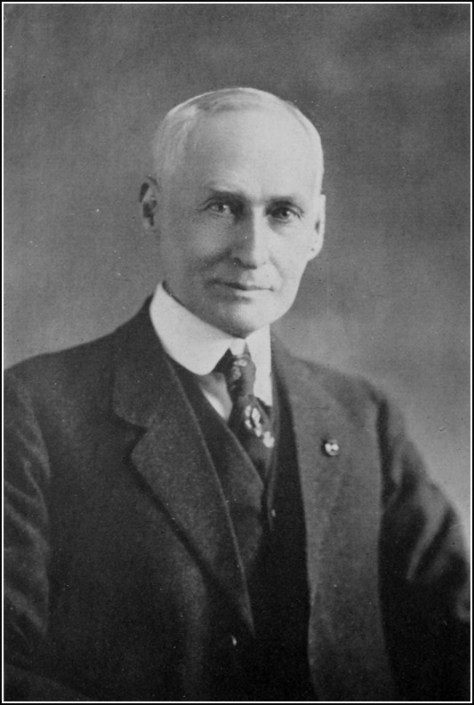

The following letters were written by Henry Loomis (1839-1920) of Fayetteville, Onondaga county, New York, who enlisted as a private in the 146th New York Infantry and was mustered into Co. G as a sergeant on 30 August 1862. He was promoted to 1st Sergeant on 10 December 1862 and then commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant of Co. K on 1 February 1863. In July 1864, he was transferred to Co. D, and then made 1st Lieutenant of that company on 16 September 1864. He mustered out of the regiment as Captain of Co. D on 16 July 1865 at Washington D. C.

Henry was born in Otsego county to Noah Coleman Loomis (1792-1857) and Mariah Meech (1799-1843). After his parents died, Henry resided for a time with his relatives in Fayetteville. He entered Hamilton College in 1860 but left school in 1862 to enlist in the 146th New York Volunteers. His obituary states that he participated in 24 battles during the war. After he mustered out in 1865, he returned to college and graduated in 1866. “He then entered Auburn Theological Seminary and was appointed by the American Board to be a missionary to China after graduation, but ill health kept him stateside, and for a year he was pastor of the Presbyterian Church at Jamesville, New York. There he met and married Jane Herring Greene on March 6, 1872. Jane’s brother, Rev. Daniel Crosby Greene, was a distinguished missionary with the American Board in Japan, and by the end of 1872 they went out to Japan. Henry organized and became the first pastor of the Yokohama Shiloh Church at Onoye-cho. After 4 years in the field, he furloughed to the States. When he returned to the field, it was under the service of the American Bible Society. In Japan, and in coordination with the British Societies, he was responsible for the publication and distribution of the Scriptures in Japan.

Ill health plagued him again forcing him to spend 5 years in California. His interest in horticulture resulted in his introducing the Japanese Persimmon into the United States. His reports to the US Department of the Interior on the Gypsy Moth in Japan and the natural predators that kept it in check helped save the US apple industry. During the Sino-Japan and Russo-Japan Wars, he successfully developed mutual relationships with the Japanese government and was supported by Army generals and Naval Admirals. This created a level of comfort and trust, and the Mission, known as the Bible House, was a conclave for American and other foreign visitors to Japan without governmental interference. Henry passed away in September 1920 and was buried at the Gaikokujin Bochi in Yokahama.” See Find-A-Grave.

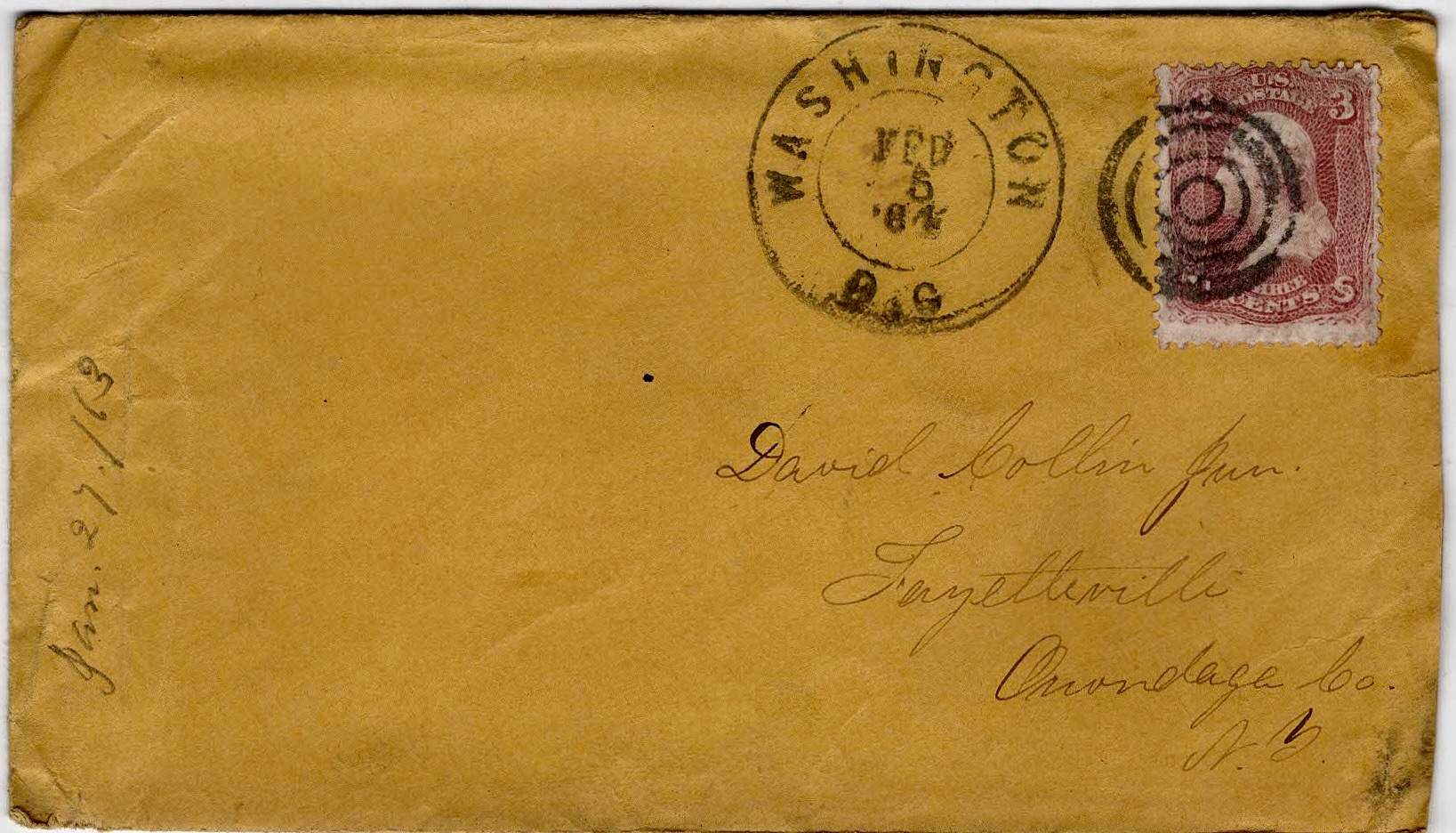

Henry wrote all of the letters to his cousin, Clara Park Collin (1850-1912) or her siblings, the children of David Collin IV (1822-1908) and Clara Park (1822-1881) of Fayetteville, Onondaga county, New York.

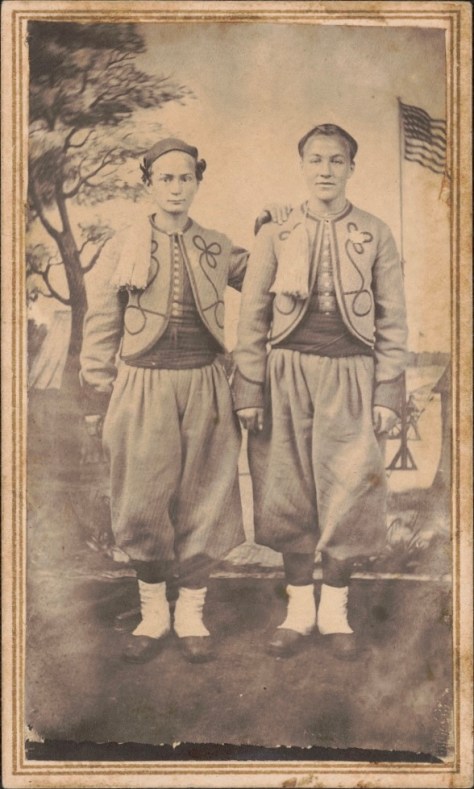

The 146th New York Infantry, also known as “Garrard’s Tigers,” was a Union Army regiment organized in October 1862 that served throughout the Civil War. This regiment at first wore the regular dark blue New York state jacket, light blue trousers, and dark blue forage cap, but when the veterans from 5th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment—a famous Zouave unit—were transferred to the 146th New York, the regiment switched over to the colorful Zouave dress on 3 June 1863 at Falmouth, Va. The zouave uniform consisted of large baggy trousers, blue in color, which were fastened at the knees; a fez cap, bright red in color, with red tassel; a long white turban which was wound around the hat, but worn only for dress parade; a red sash about ten feet long which was wound about the body and afforded a great comfort and warmth; and white cloth legging’s extending almost to the knees. The new uniform was not actually Zouave, but rather the colorful dress of the French-Turco style.

The 146th New York fought in a number of major battles including Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg (see Garrard’s Tigers at Gettysburg, July 2, 1863), and the Wilderness, and was present at Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. I have yet to identify the soldier from the 146th NY Volunteers who wrote two great letters of the Battle of Fredericksburg and the Battle of Chancellorsville. See—1862-63: “George” to his Family at Home.

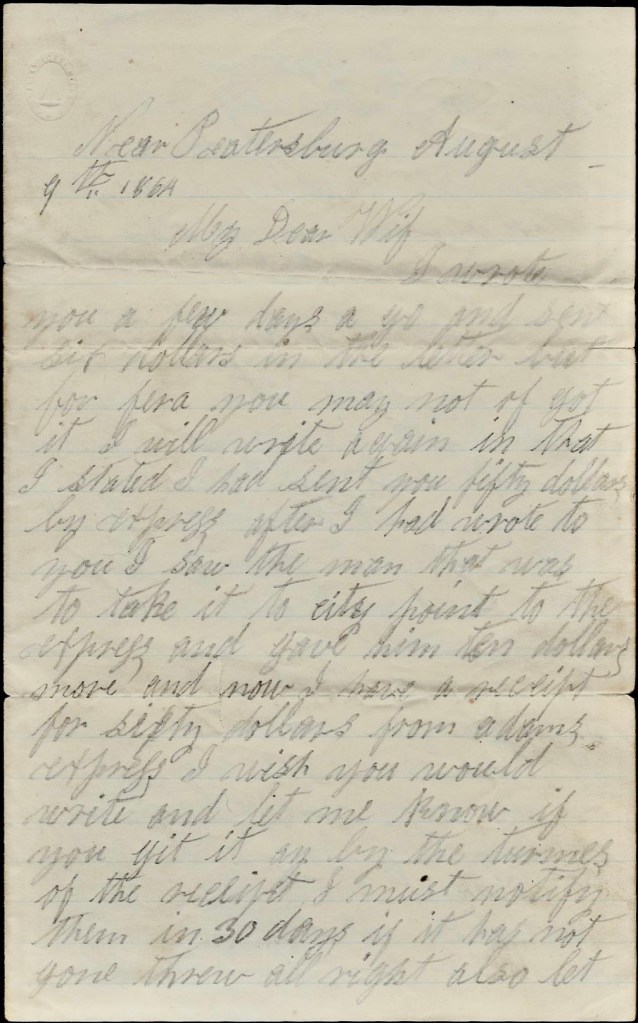

Letter 1

Camp near Potomac Creek, Virginia

March 5th 1863

Dear Cousin Clara,

You wished me to write to you and let you know how we lived in camp and I will endeavor to do so although I can give you but a very imperfect idea of camp life. It consists of two parts which in many respects are quite similar yet in experience there is a vast difference. The first part is life in the ranks and the second is life as an officer.

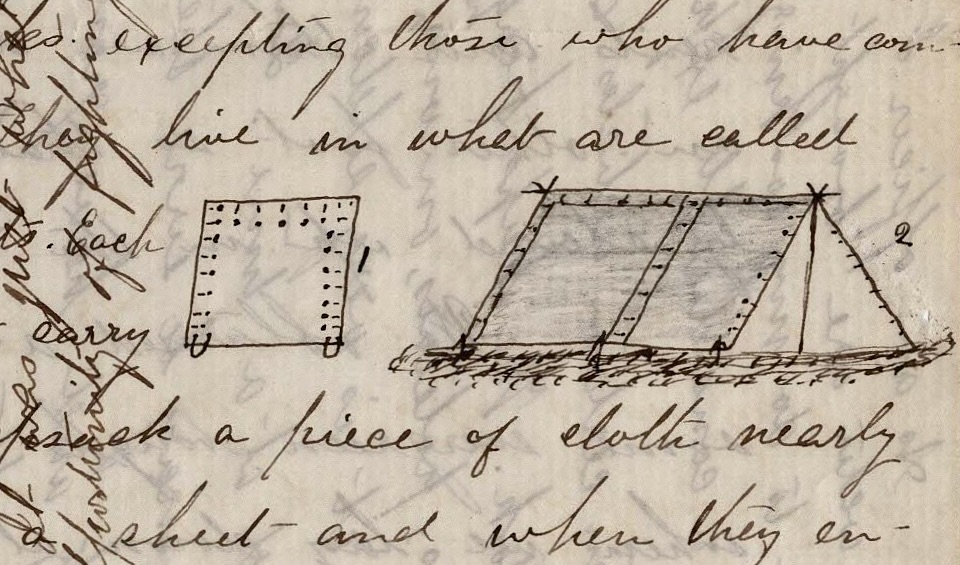

All persons are considered as being in the ranks excepting those who have commissions. They live in what are called shelter tents. Each soldier has to carry in his knapsack a piece of cloth nearly as large as a sheet and when they encamp from two to six will button their pieces together and form a tent. Figure No. 1 is a picture of a piece with the buttons and the button holes and also the loops for fastening the edges down. Figure No. 2 is a picture of the tent after it is struck. You see that it is held up in the middle by a pole which rests upon the two crotches.

The tent, which I occupied until about two months ago was like that which you see in the picture. We had a fireplace built of sod in one end which would work very well when the wind was in the right direction. We rained the tent up from the ground about a foot by means of boards and rails and then we dug down about another foot so that we could nearly stand up in the center.

We obtained a little [illegible] and some evergreen boughs as bedding and when we lay down at night, there was just room enough in one end to stow away our canteens and haversacks. Our knapsacks we used as pillows. When the weather was cold and the chimney would not draw, we had to use our blankets to keep warm. We brought the wood upon our backs and we sometimes would go a mile or more to obtain it.

The reveille sounds about daylight in the morning when we were all obliged to be up and answer to roll call. Our company cook would generally have a cup of coffee ready for us then which with a piece of pork and hard bread constituted our breakfast. For dinner we would have either pork, (potatoes about once a fortnight) fresh beef, beans or some kind of soup. For supper we would sometimes have rice but we generally had coffee and hard bread. We would get tea about twice a week. We had just about sugar enough to sweeten our coffee so that is we used it in that way we had to eat our rice without, or vice versa.

We had quite a number of ways of making our hard bread relish such as frying, roasting, soaking in coffee, and we would also pound them up and make cakes and puddings. I have been so hungry at times that a piece of cold pork and “Hard Tack” (the name for our bread) would taste better than any cake that I ever ate at home. I do not wish to complain, however, as i think that very few of the volunteer regiments have fared as well as ourselves.

As to work, we always had enough to do to keep us healthy. Besides drilling, we had to bring wood and water, clean up our clothing, guns, and the streets, do guard duty and other things too numerous to mention. We had about one candle for our tent every three or four days so that when we wished to sit up at night we had to burn the lard which came from the pork. To eat with we had a tin cup, a tin plate, a knife, a fork, and a spoon. We would generally sit in the manner of a tailor and use our laps as a table. Some of the time we were fortunate enough to obtain a board or box for that purpose.

Such was my life for nearly two months and such is the life of nearly the whole “Union Army.” Soft bread has lately been added but that will be discontinued as soon as the army begins active operations. It was just what I expected and I have never regretted that I have an opportunity of fighting for my country.

As an officer, I have plenty to eat and plenty of time. My wood and water are brought by the company and I expect to have a servant soon to do my cooking. For the present I do my own cooking but as I have a considerable experience of late, I make it do very well. We can obtain certain articles at the commissaries as cheap as in Washington or New York. He keeps bread & fresh beef, pork, rice, coffee, tea, candles, sugar, beans, potatoes, onions, and molasses. This is the whole list of articles but it is very seldom that they have more than half of them on hand at a time. You see that we can live very comfortable now and you may be sure that I can appreciate the change. I am very hearty and have grown fleshy so fast that I don’t believe I can wear the suit of clothes which I sent for. Did I not think that I have another work to do I should be perfectly contented to be a soldier.

I hear that there is a revival at Lafayetteville. It is my prayer that if may prove a blessing to you all. Each one of you must write as often as possible for not even my commission gave me so much pleasure as your letters. Please accept the kindest regards of — Cousin Henry

Camp near Potomac Creek

March 9th 1863

I have nearly finished a letter for Eddie but as I am Officer of the Day, I cannot complete it before tomorrow. The money and barrel have arrived in safety and were very acceptable. I will enclose two laurel rings for your Mother and a bone one which was manufactured by a Union prisoner while confined in Richmond jail. The bone was given him as his rations. I will enclose some pebbles also from Potomac Creek. In haste, — Henry

Letter 2

On picket near Potomac Creek, Virginia

June 1st 1863

Dear Cousin,

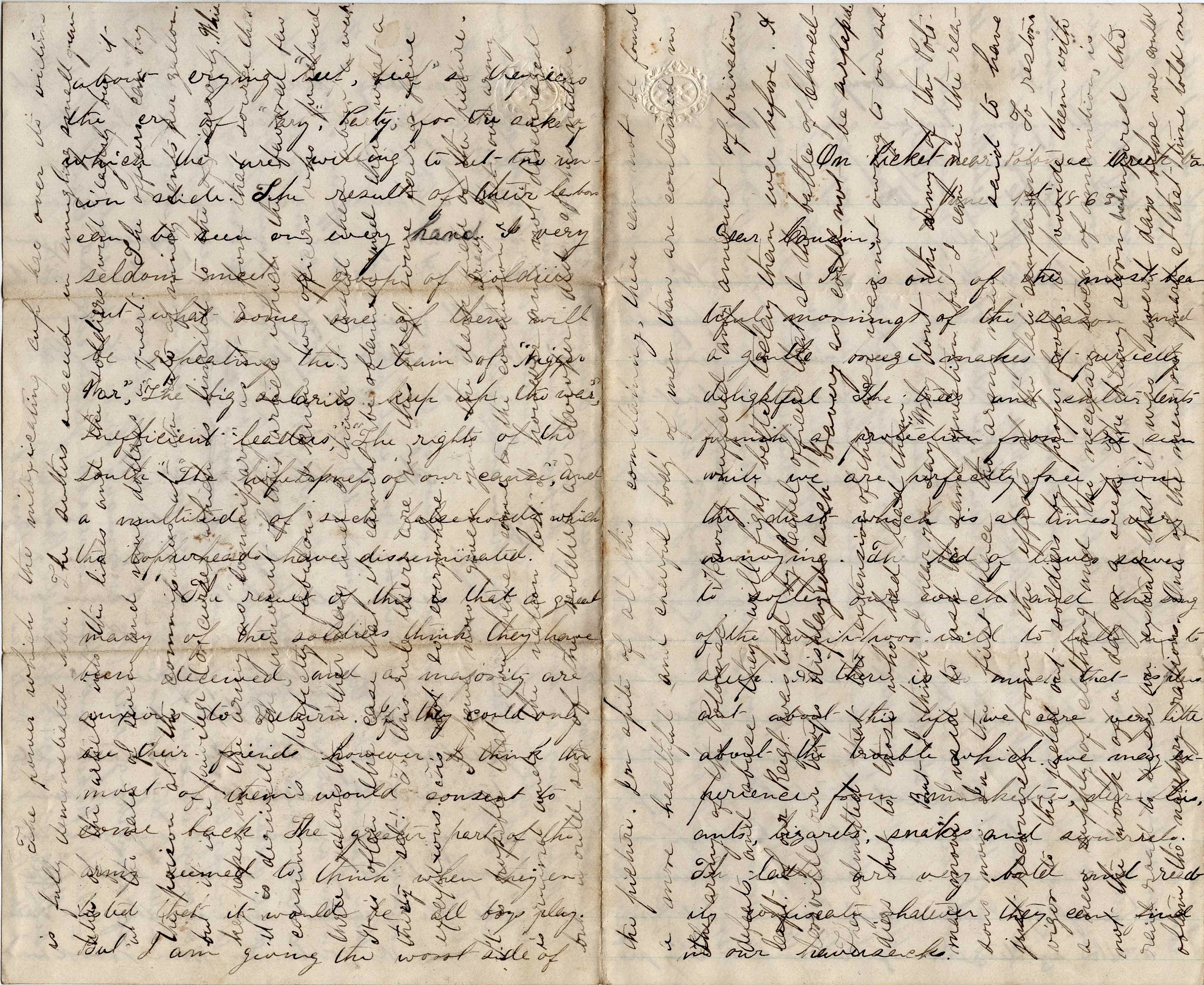

It is one oof the most beautiful mornings of the season and a gentle breeze makes it perfectly delightful. The trees and shelter tents furnish a protection from the sun while we are perfectly free from the dust which is at times very annoying. The bed of leaves serves to soften our couch and the song of the whippoorwill to lull us to sleep. As there is so much that is pleasant about this place, we care very little about the trouble which we may experience from mosquitoes, deer flies, and lizards, snakes and squirrels, The latter are very bold and readily infiltrate whatever they can find in our haversacks.

I was along the line last night from twelve until two and shall be on again today from ten to twelve. The rest of the time I can read, write or sleep so that it is much preferable to bring in camp. Having said so much by way of preface, I propose to tell you whatever I think will be interesting that has not already been written.

Although I have been in the two most bloody battles of the war, yet I have not seen more than fifty of the wounded and scarcely any bad. The reason of this is that I have as far as possible avoided such sights. I have not seen men who were struck within a few feet of me. As others had been detailed to take care of such, it was our duty to keep our places and be ready for action. Of necessity, I have seen some but not the excitement of a contest. They produce nothing like the effect which they would at other times. In the late fight [Chancellorsville], a sergeant was struck with a shell but a short distance in front of me. As I [ ] he gave me such an imploring look as I shall never forget. He was borne to the rear a few minutes afterwards by the Chaplain and some others.

As to the present condition of our army, it has been considerably reduced by the departure of old regiments but they have not lost their confidence in Hooker nor can Northern papers convince them that the Rebels were not the greatest sufferers. If Northern editors had their deserts, a great number of them would be enjoying the hospitalities of the “Sunny South.” They are the greatest enemies that we have to contend with. As John Hook went about crying “beef. beef”, so they [ ] the cry of “Party, Party” for the sake of which they are willing to let the Union slide. The results of their labors can be seen on every hand. I very seldom meet a group of soldiers but what some one of them will be repeating the strain of “Nigger War”—“Inefficient Leaders”—“the Rights of the South”—“The hopelessness of our Cause,” and a multitude of such falsehoods which the Copperheads have disseminated. The result of this is that a great many of the soldiers think they have been deceived and a majority are anxious to return if they could only see their friends. However, I think the most of them would consent to come back. The greater part of the army seemed to think when they enlisted that it would be all boys play.

But I am giving the worst side of the picture. In spite of all the complaining, there cannot be found a more healthful and cheerful body of men than are contained in the Army of the Potomac. Having suffered any amount of privation, defeats, and abuse, they will fight better today than ever before. A captain of our regiment was told by Rebel officers that at the Battle of Chancellorsville, our troops displayed such bravery as could not be surpassed. They admitted that the extension of this war was not owing to our soldiers but to those who had lead them.

But I think I hear you say, “Why don’t the Army of the Potomac move?” I used to ask the same question but I can see the reason now. In the first place, the army may be said to have just recovered from the effects of the late campaign. To restore vigor to the jaded out soldiers by proper food, to provide them with a new supply of clothing and the necessary stock of ammunition, is not the work of a day or a week. The heavy storm had injured the railroad to such an extent that it was several days before we could obtain the necessary rations. One of the men on guard at that time told me that all he had for breakfast was two Hard Tack (which is about the same as two soda crackers) and this was the condition of the whole company; and I think I may say of the regiment. Although they were short of food for several days, they endured it like heroes and yet would hardly hear a word of complaint. It is a shame that such an army should be cursed by Northern influence. Were the same efforts used to encourage that now tend to dishearten, the days of this Rebellion would soon be numbered.

Another reason why we do not move is that a definite plan must be perfected and every arrangement made. Even when plans have been made, which would seem to ensure success, a very slight matter would render the whole impracticable. An instance of this was the delay in the pontoons reaching Fredericksburg. The occurrence of a storm or the movement of the enemy’s forces has frequently rendered force here to prevent our crossing in their face; and they have now taken preventions against another movement like the last. The only possible way is to keep quiet and ready for any opportunity that may offer.

One thing has been fully demonstrated and that is that the Rebel army is not to be despised as they always have the advantage and fight with perfect desperation. I used to hear windy orators boast how they would make them skedaddle but for my part, I “can’t see it.”

As to the worst condition of the army, a greater part of the soldiers spend their leisure time in card playing and a great many of them gamble. In this they have the example of the officers, many of whom are very proficient in the art. Capt. [James] Stewart told me yesterday that a certain lieutenant of our regiment had a debt amounting to two hundred dollars. The great apology for the practice is the want of something to occupy the mind. The want of paper or books causes a great number to engage in card playing merely for amusement. Much of it would be prevented if there was only a proper supply of reading matter. For want of something else, the enormous price of ten cents is paid for a daily paper and the miserable yellow covered trash of the sutlers is equally devoured. Profanity is also [practiced?] although I think not as much as formerly.

The power which the intoxicating cup has over its victims is fully demonstrated here. The sutlers succeed in smuggling small quantities of the article into the lines and the soldiers will “eagerly” but it at the rate of seven and nine dollars a quart. The officers can but the poison at the commissaries at the rate of ninety cents per gallon but it is a privilege (or curse) which is limited to the officers only. Whiskey passes in the army as “commissary” as it is from that source that it is desired. The amount of this article which the favored few consume is perfectly fabulous. I know two officers who purchased three gallons the other day and I think it lasted them about a week. It is often the case that it cannot be obtained and then what a thirsty set! To this rule there are in the regiment some four or five exceptions. Tis not so elsewhere.

I have now given you the dark side of the picture. It is possible that you have come to the conclusion that our army is ruined and the Nation lost. I however am not discouraged but I will say of the soldiers as Cowper did of his native country, “With all their faults, I love them still.” They have as high an appreciation as ever of what is true and good while they openly condemn what is low and mean. Very few are anxious to fight when they can help it, but a coward is utterly despised, Though divided into clans according to their various tastes, yet they have a common sympathy which is often seen displayed in the dividing of the last morsel.

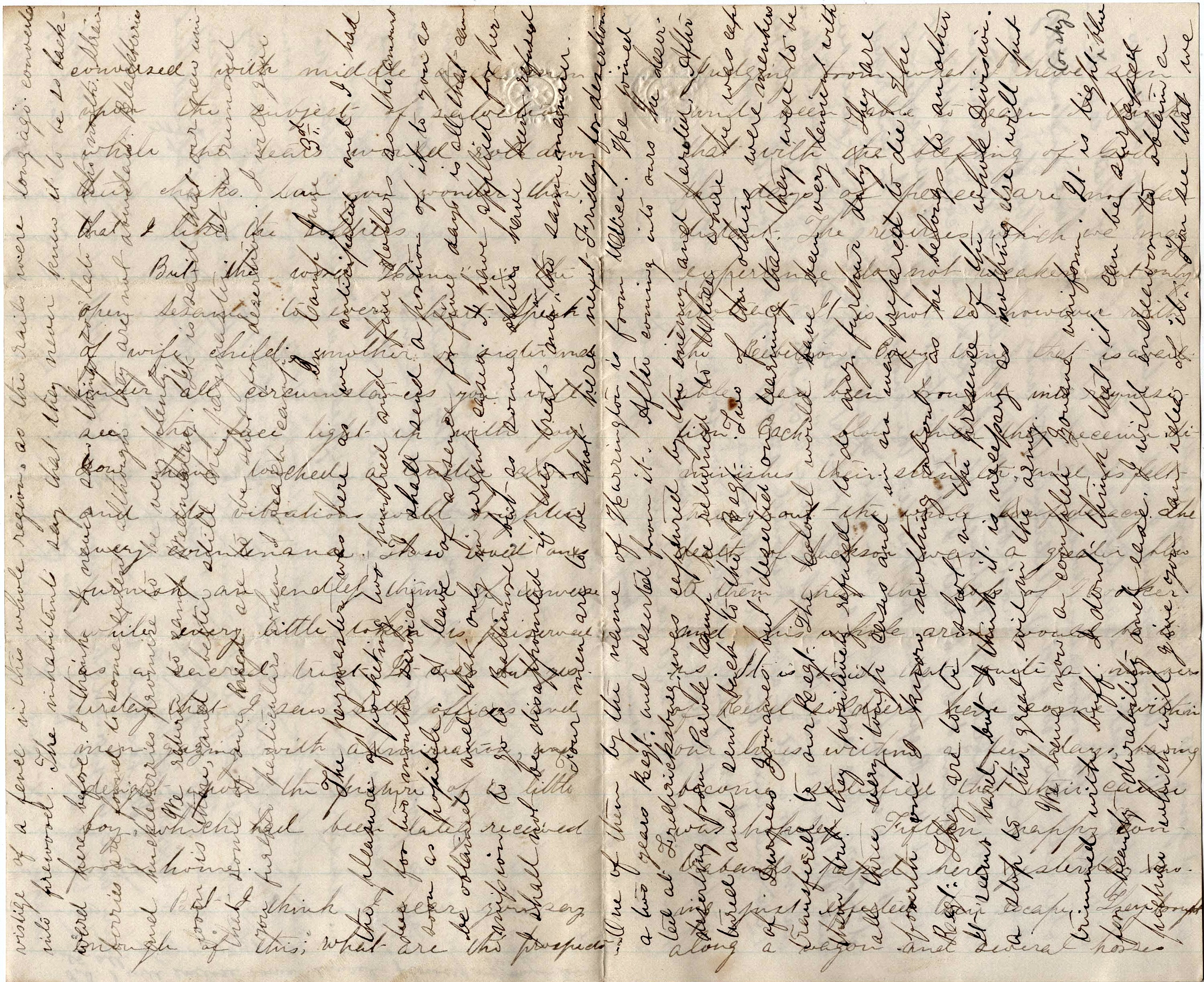

As a general thing, our religious meetings are largely attended. Although many of those which are often present are non professors, yet they are exceedingly respectful and attentive. They are always ready to converse on religious subjects and will very thankfully receive any reading matter of that class. I have conversed with middle-aged men upon the subject of salvation while the tears would roll down their cheeks. Can you wonder then that I like the soldiers.

But the word “Home” is the open [ ] to every heart. Speak of wife, child, mother, or sister and under all circumstances you will see the face light up with joy. You have touched a tender chord and its vibrations will brighten every countenance. Those loved ones furnish an endless theme of conversation while every little token is preserved as a sacred trust. It was but yesterday that I saw both officers and men gazing with admiration and delight upon the picture of a little boy which had been lately received from home.

But I think I hear you say, “Enough of this; what are the prospects?” Judging from what I have seen and been able to learn, I think that with the blessing of God, the days of peace are not far distant. The reverses which we may experience does not weaken but only protract. It is not so, however, with the Rebellion. Everything that is available has been brought into requisition. Each blow which they receive diminishes their strength and is felt throughout the whole Confederacy. The death of [Stonewall] Jackson was a greater blow to them than the loss of Hooker and his whole army would be to us. It is said that quite a number of Rebel soldiers have come within our lines within a few days, having become satisfied that their cause was hopeless. Fifteen happy contrabands passed here yesterday morning, just effected their escape. They brought along a wagon and several horses belonging to their master. There seems to be but one way that the Rebels can keep their property secure, and that is to place them in this army where they can be constantly guarded.

As to the general character of the country in this vicinity, the soil is sandy and I should think if properly cultivated it would be very productive. It is gently undulating and can be very easily tilled. The style of farming here seems to have been in succession of crops as long as it is profitable and then the land is left to grow up to timber. I have passed through many pieces of good timber land where the rows of corn could be distinctly traced. The timber consists of oak, ash, sweet gum, white wood, pine, red cedar, and walnut. Peach, apple, and pear trees are very abundant and thrifty. It only need Norther industry here to make this country a perfect garden. Wood, water, soil and climate are all as favorable as could be desired.

The style of dwelling here is about fifty years behind the times. Omitting the Negro quarters, the buildings here will not average as good as those between your house and Hartsville, omitting Mr. Gardner’s. Men owning five and six hundred acres of land live in houses which present no better appearance externally than the one which John Roe occupies although they are much more commodious. The negroes have almost entirely deserted the country. The few inhabitants that remain are as a class incapable of military service. They profess to be “Union” or indifferent, but I should think a majority of them are in favor of the South.

It has been several weeks since we have had any rain here and the ground has become so hard that it has been impossible to till it. A few patches of corn were put in by the natives but I imagine that they have been ruined by the drouth. There is nearly vestige of a fence in this whole region, as the rails were long ago converted into firewood. The inhabitants say that they never knew it to be so backward here before. I think I never saw things so late at the North. Strawberries are found to some extent although they are not abundant. Blackberries and huckleberries promise to be very plenty.

We return to camp Wednesday. It is said that our new uniform is there and better still, the paymaster. It is rumored that some of our regiment are to shot for desertion. I will give you further particulars when I reach camp.

In camp, June 3rd. The paymaster was here as we anticipated and I had the pleasure of pocketing two hundred and five dollars as the amount due for two months service. I shall send a portion of it to you as soon as possible. A leave of absence for five days is all that can be obtained and that only in urgent cases. I have applied for permission to go to Baltimore but as some of them have been refused, I shall not be disappointed if they treat me in the same manner.

Four men are to be shot here next Friday for desertion. One of them by the name of Harrington is from Utica. He joined a two-year’s regiment and deserted from it. After coming into ours he deserted at Fredericksburg, was captured by the enemy and paroled. After deserting from Parole Camp, he returned to Utica where he was captured and sent back to the regiment. Two of the others were members of Duryee’s Zouaves but deserted on learning that they were to be transferred to our regiment. The Colonel would have been very lenient with them but they positively refused to do any further duty. They are all three very tough cases and in no way prepared to die. The fourth one I know nothing about as he belongs to another regiment. They are to be shot in the presence of the whole division. It seems hard but I think it is necessary as nothing else will put a stop to this great evil in the army.

We have now a complete Zouave uniform. It is bright (or sky) blue, trimmed with buff. I don’t think that it can be surpassed for beauty, durability and ease. I will endeavor to obtain a picture which will give you an idea of it. You see that we are not going to be behind anybody.

One thing more and I will conclude this medley. There is not a paper that I have been able to get hold of that can be relied upon for information covering the army. You have undoubtedly observed the conflicting statements that may always be found. Some regiments have gained a most brilliant reputation by the circulation of absolute falsehoods. Instances of this kind have come under my own observation. I think that I speak without any prejudice when I say that the Republican press is far the most reliable. In this respect the Tribune ranks high. I cannot speak of the Post as I never see it. Everything seems to be magnified. A slight success becomes a splendid victory and the least reverse a terrible disaster. If you will pardon me for a bit of advice, I would simply say “Look on the brightest side and leave the result to Providence.”

I am greatly indebted to you for your promptness in forwarding funds. I hope that the money which I shall be able to send home from time to time will be equally accepted. If you have been able to derive any pleasure or profit from this lengthy epistle, the object in view will be fully accomplished by, — Cousin Henry

P. S. I will enclose some laurel; flowers and much love to all.

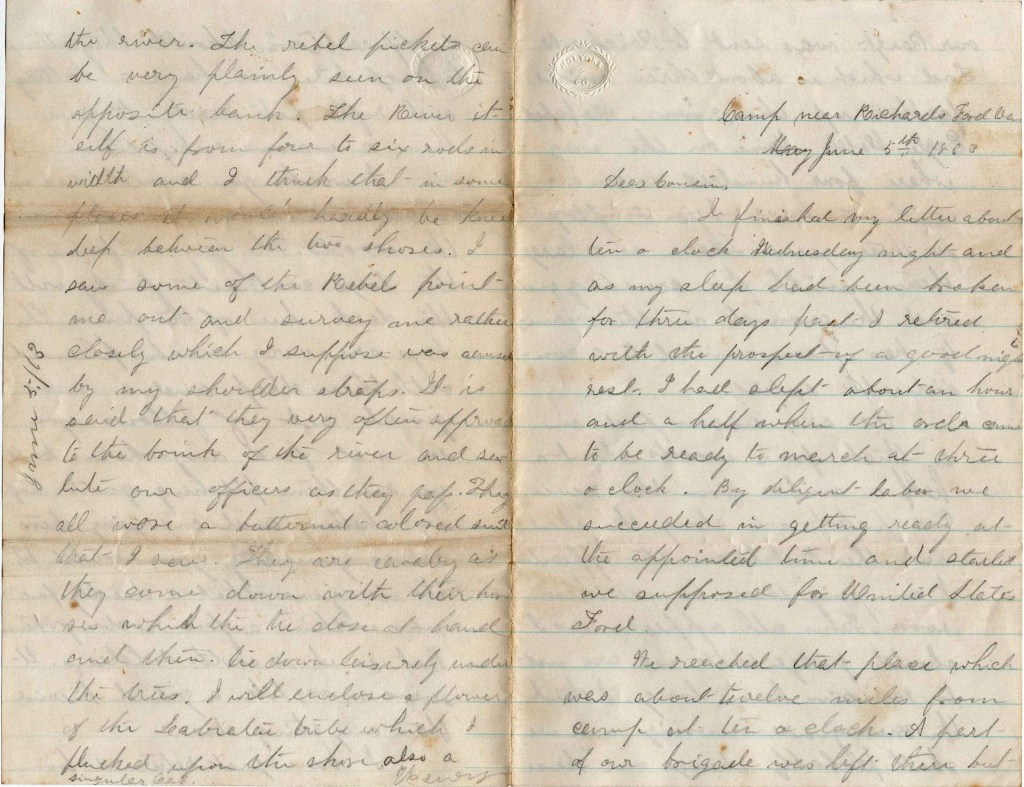

Letter 3

Camp near Richard’s Ford, 1 Virginia

June 5th 1863

Dear Cousin,

I finished my letter about ten o’clock Wednesday night and as my sleep had been broken for three days past, I retired with the prospect of a good night’s rest. I had slept about an hour and a half when the order came to be ready to march at three o’clock. By diligent labor we succeeded in getting ready at the appointed time and started we supposed for United States Ford.

We reached tyhat place which was about twelve miles from camp at ten o’clock. A part of our brigade was left there but our regiment was sent to Richard’s Ford which is about three miles farther up the river. We passed “Eagle Gold Mine” 2 on the way where four hundred men are said to have been employed for three years. There is a large steam mill for crushing quartz and the ground in this vicinity has been mined to a considerable extent.

We are encamped in a thick pine woods about a half a mile from the river. Our pickets are along the shore and the Rebels on the opposite. I am going down to see them soon. From all appearances I should judge that we are not to remain here long. I think the enemy are moving and we shall probably change our “base of operations.” Should they attempt to cross here, we have a battery and rifle pits ready to give them a warm reception.

I wish you could see us as we are encamped here in the woods. The gay uniform of the boys contrasts finely with the dark hue of the pines. The boys are very much pleased with their dress and a more jovial set of fellows you cannot find anywhere. Could you see them pitching quoits, laughing, chatting and enjoying themselves generally, you would little imagine that a deadly foe was within a few rods of them. But so it is with soldiers. It seems more like a grand picnic than anything else.

I have just returned from the river. The rebel pickets can be very plainly seen on the opposite bank. The river itself is from four to six rods [30 yards] in width and I think that is some places it would hardly be knee deep between the two shores. I saw some of the Rebels point me out and survey me rather closely which I suppose was caused by my shoulder straps. It is said that they very often approach to the brink of the river and salute our officers as they pass. They all wore a butternut colored suit that I saw. They are cavalry as they come down with their horses which they tie close at hand and then lie down leisurely under the trees.

I will enclose a flower of the Labratar [?] tribe which I plucked upon the shore. Also a singular leaf. — Henry

1 Coming upriver from the Rapidan confluence, the first Culpeper ford is Richard’s Ford.

2 Stafford’s most productive mine was Eagle, also known at various times as the Rappahannock Gold Mine, which operated from before 1833 to around 1897. By 1847, it was operated by the Virginia Gold Belt Company of Philadelphia who changed the name from Rappahannock to Eagle Gold Mine. By 1850, it was owned by Bettle Paul of Philadelphia. In 1860, Samuel Smith of Boston bought it. Mining was carried on here continuously from the 1830s until 1861. Eagle Mine re-opened after the Civil War and mining continued sporadically here until around 1897.

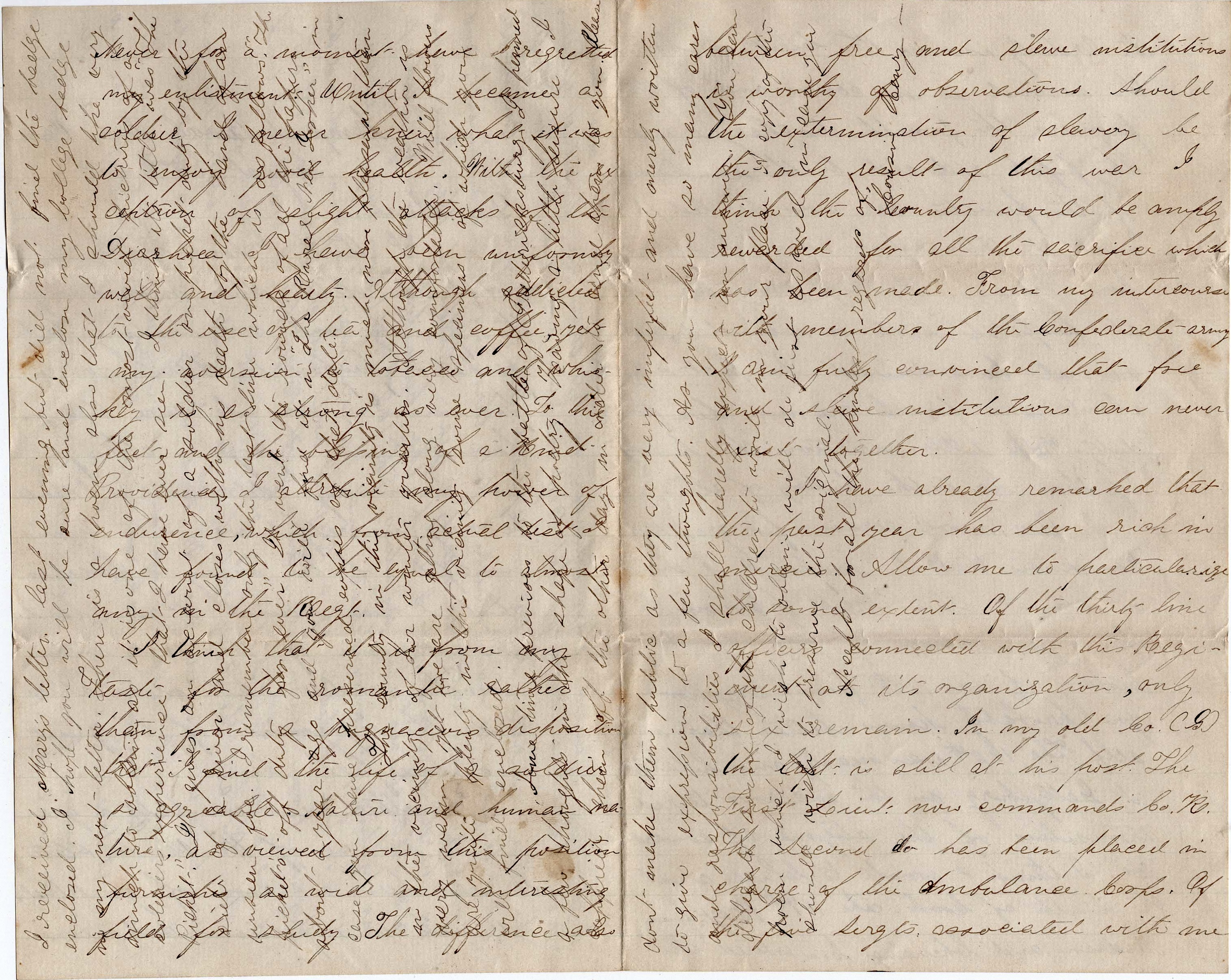

Letter 4

Camp at Beverly Ford, Virginia

August 22nd 1863

Dear Cousin,

I think I have written to about all of the other members of the family and not wishing to be partial, I propose to address you a few lines. You may be sure that you have not been forgotten although not previously addressed, as I should be very ungrateful were I to be unmindful of the many kindnesses which I have received at your hand. The experience of the last twelve months renders still more attractive the enjoyment of a quiet and cheerful home.

Another week completes a year in the service of the United States. It has been a season of great trial, yet rich in experiences and mercies. Never for a moment have I regretted my enlistment. Until I became a soldier, I never knew what it was to enjoy good health. With the exception of slight attacks of the diarrhea, I have been uniformly well and hearty. Although addicted to the use of tea and coffee, yet my aversion to tobacco and shiskey is so strong as ever. To this fact, and the blessing of a kind Providence, I attribute my power of endurance, which from actual test I have found to be equal to almost any in the regiment.

I think that it is from my taste for the romantic rather than from a pugnacious disposition that I find the life of a soldier so agreeable. Nature and human nature, as viewed from this position, furnishes a wide and interesting field for study. The difference also between free and slave institutions is worthy of observations. Should the extermination of slavery be the only result of this war, I think the country would be amply rewarded for all the sacrifice which has been made. From my intercourse with members of the Confederate army, I am fully convined that free and slave institutions can never exist together.

I have already remarked that this past year has been rich in mercies. Allow me to particularize to some extent. Of the thirty line officers connected with this regiment at its organization, only six remain. In my old company (G), the Captain is still at his post. The 1st Lieutenant now commands Co. K. The 2nd [Lieutenant] has been placed in charge of the Ambulance Corps. Of the five sergeants associated with me, the Orderly is now 1st Lieutenant in Co. E, the 2nd is in command of the Pioneers, the 4th discharged, and the Fifth reduced to the ranks. Six of the privates are now paroled prisoners at Alexandria. Six have died from disease. A large number are at hospitals sick or wounded, and several have deserted. In fact, only about one-fourth are now here for duty. With little variation the history of this company is the history of all.

One more reason for the gratitude you know that I proposed to enlist in several other regiments previous to the organization of the 146th. The history of the 114th (from Cazenovia) you probably know better than myself. The 126th was nearly annihilated at Gettysburg in the endeavor to rid themselves of the stigma of cowardice. I think I wrote to Clare about the death of Cook. The 157th Regiment (from Madison and Chenango counties) entered the service about the same time as ourselves. Chancellorsville and Gettysburg have reduced their number to less than one hundred effective men. Of two classmates in that regiment, one was wounded twice in the face, the other was killed or captured. The 117th (which left Oneida previous to us) has been building forts, throwing up entrenchments, and doing garrison duty for nearly a year. Although they have seen no hard fighting yet, I think they have lost more by sickness and other causes than ourselves.

The 152nd Regiment (from Otsego) has seen no fighting, yet incompetence and severe marching has reduced them to a mere skeleton of a regiment. I will not criticize the 199th as they are from Onondaga. Tis a good regiment, but I could not think of exchanging. The history of our regiment you are already familiar with. Of all the regiments that have come under my observation, ours has been the favored one. We have already required a reputation to be envied and in all probability it will yet stand second to none.

Our uniform is acknowledged to be the finest in the service. A location where we can be seen is all that is required to render us famous. Perhaps I estimate the 146th too highly. If so, the future will reveal it.

I received Mary’s letter last evening but did not find the badge enclosed. I hope you will be sure and enclose my college badge in my next letter. There is a poem also that I should like very much to obtain as it is one of the most vivid pictures of a soldier’s experience that I have ever seen. I think its title was “The Picket.” It gives an account of a soldier on picket duty by the side of a river and closes with his death by the hand of an unseen foe. I remember only the last line which is as follows: “The pickets off duty forever.” It went to the rounds of all the papers about a year ago and you will find it in The Rural New Yorker, in case you have preserved copies of that date. 1

The country in this vicinity is much more pleasant than in the vicinity of our winter quarters. Although the weather is very warm yet, we are getting along very comfortably. Wild flowers are quite plenty in this vicinity, some specimens of which you will find enclosed.

Sometime previous to the Battle of Fredericksburg, I penned a few thoughts in the shape of poetry. Having a little leisure, I copied them off the other day in order to send them to you. Please don’t make them public as they are very imperfect and merely written to give expression to a few thoughts. As you have so many cares and responsibilities, I shall hardly expect an answer. You can delegate some of the children to write in your place. A copy of the poem which I wish to obtain will do just as well in case you should wish to preserve the original.

Accept for all the kindest regards of—cousin Henry

1 “All Quiet along the Potomac Tonight” was a popular Civil War song, published in 1863. The lyrics, written by Ethel Lynn Beers, were originally published as the poem “The Picket-Guard” in Harper’s Weekly in 1861. The song was composed by John Hill Hewitt in 1863. The last stanza reads:

Hark! Was it the night wind that rustled the leaves,

Was it moonlight so wondrously flashing?

It looks like a rifle — “Ah! Mary, good-bye!”

And the lifeblood is ebbing and splashing.

All quiet along the Potomac tonight,

No sound save the rush of the river;

While soft falls the dew on the face of the dead –

The picket’s off duty forever.

“All quiet along the Potomac tonight!”

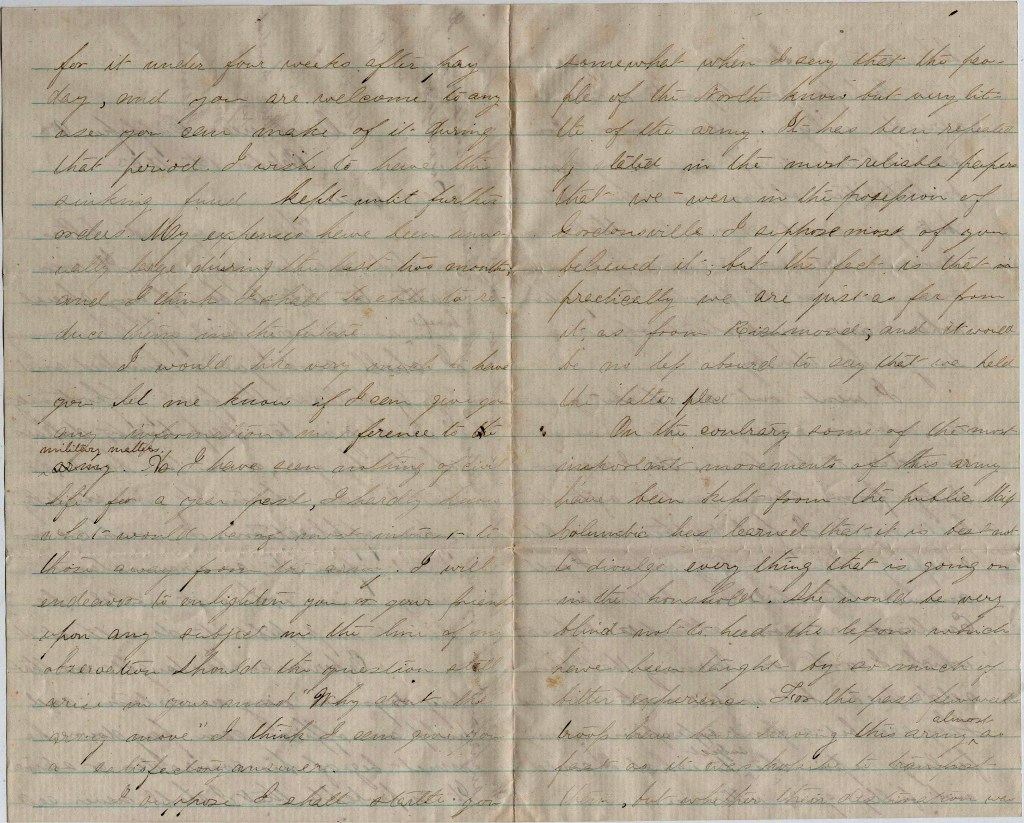

Letter 5

Camp near Culpeper, Virginia

October 1st 1863

Dear Cousin,

The money and letters reached me two days ago. It was rather too late to be of any special benefit as we were paid off this morning. I shall send you a hundred and twenty dollars the first opportunity. I wish you to keep twenty dollars of it by you or in the bank so that I can obtain it immediately upon application. I wish no interest upon it as circumstances may arise where it would be almost impossible to do without it. Experience has taught me that pay days are very uncertain and unless an officer can pay down he must beg of his comrades or starve. It is probable that I shall never call for it under four weeks after pay day, and you are welcome to any use you can make of it during that period. I wish to have this sinking fund kept until further orders. My expenses have been unusually large during the last two months and I think I shall be able to reduce them in the future.

I would like very much to have you let me know if I can give you any information in reference to military matters. As I have seen nothing of civil life for a year past, I hardly know what would be of most interest to those away from the army. I will endeavor to enlighten you or your friends upon any subject in the line of observation should the question still arise in your mind, “Why don’t the army move?” I think I can give you a satisfactory answer.

I suppose I shall startle you somewhat when I say that the people of the North know but very little of the army. It has been repeatedly stated in the most reliable papers that we were in the possession of Gordonsville, I suppose most of you believe it but the fact is that in practically we are just as far from it as from Richmond and it would be no less absurd to say that we held the latter place.

On the contrary, some of the most important movements of this army have been kept from the public. Miss Columbia has learned that it is best not to divulge everything that is going on in the household. She would be very blind not to heed the lessons which have been taught by so much of bitter experience. For the past few weeks, troops have been leaving this army almost as fast as it was possible to transport them, but whether their destination was Charleston or Tennessee, I am unable to state. Perhaps you begin to surmise already why we don’t move. you see statements of our strength, and probabilities of an immediate attack. but you must remember that our generals are no so strictly conscientious as not to practice deception when any important object can be gained thereby.

I went out on picket yesterday and was relieved this morning in order to be paid. As I was on duty from eleven until after two last night, I feel rather more like sleeping than writing letters. I will answer the children’s letters soon. Enclosed are some attempts at poetry which I wrote on learning that those addressed had united with the church. They are but a faint expression of my feelings upon the subject to which I could not fully give utterance.

We may spend the winter here and you may [know] I should not be surprised if my next was dated from Morris Island or Chattanooga. It is useless even to surmise what is in the future, Providence being with us for the present, it matters not. With kindest regards to all my friends, I remain as ever, simply Henry

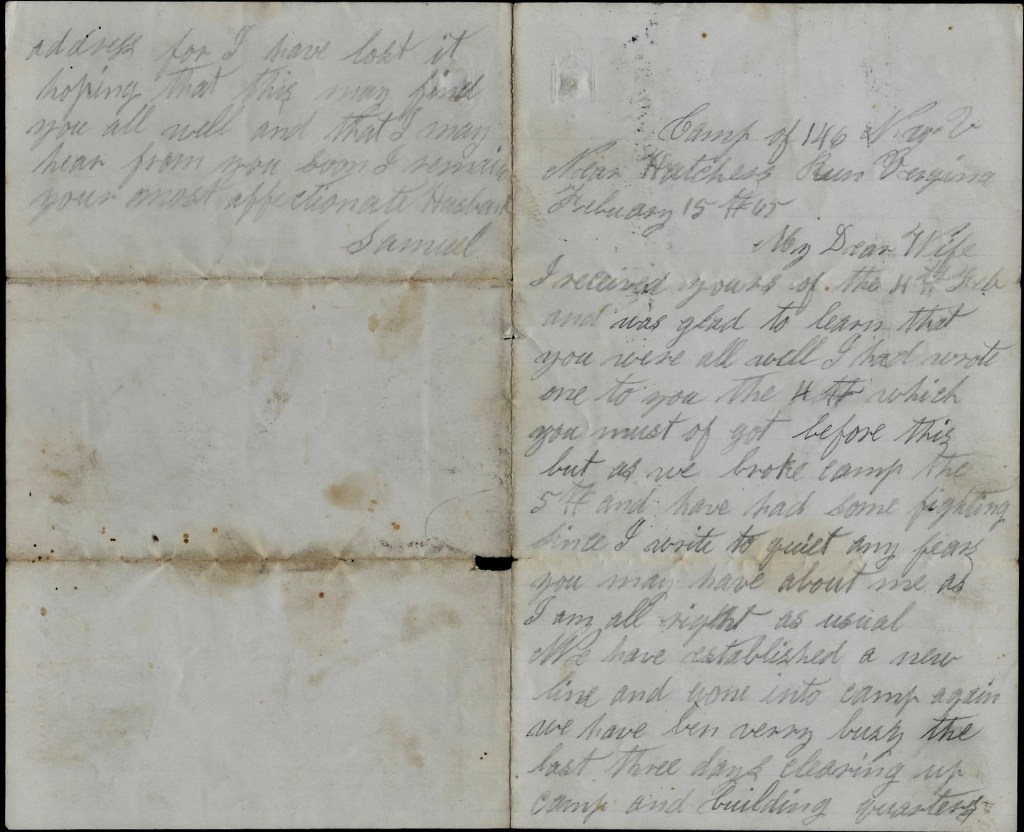

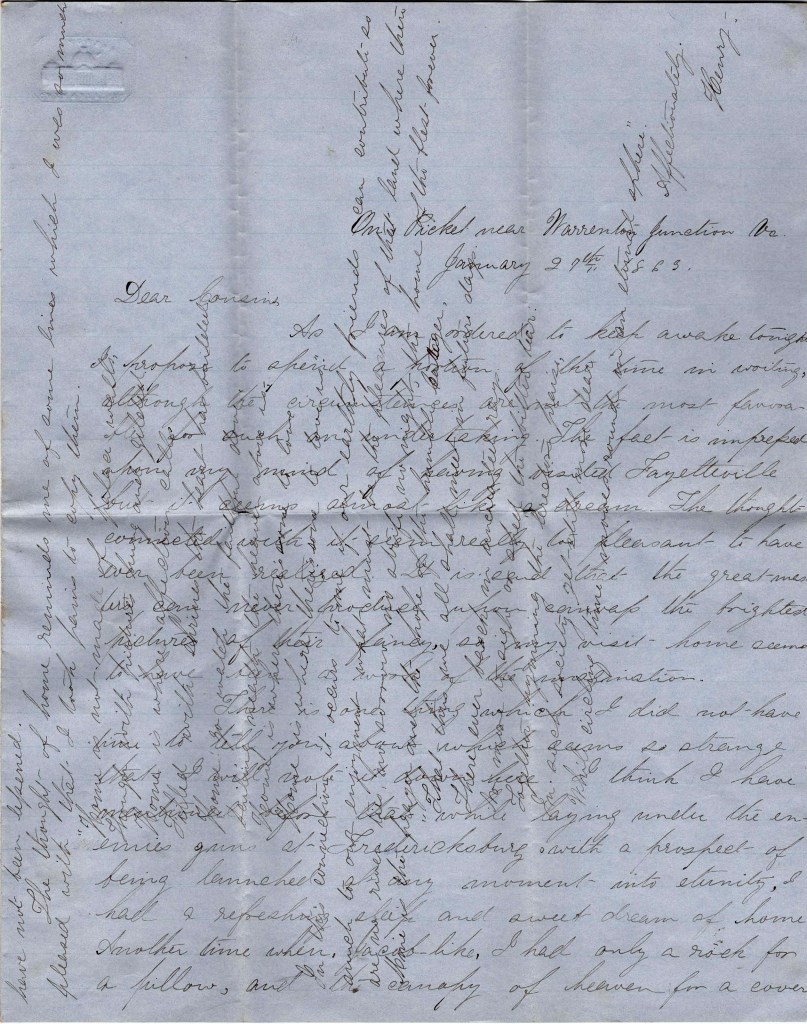

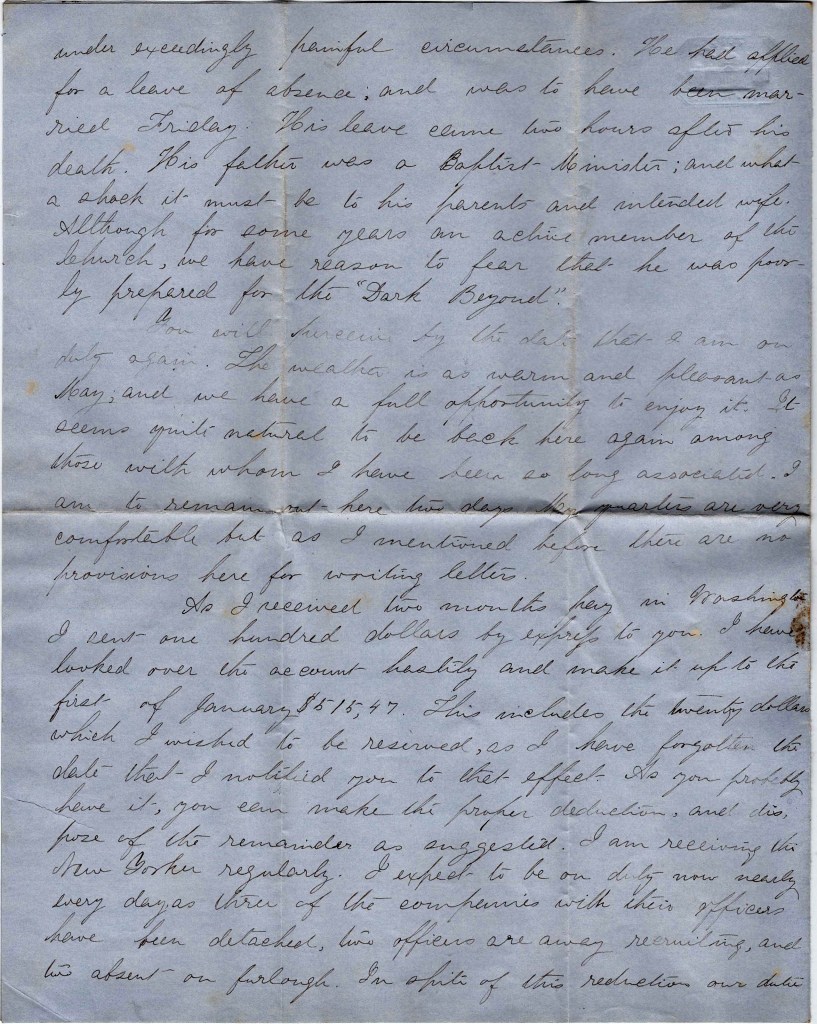

Letter 6

On picket near Warrenton Junction, Virginia

January 27th 1863 [should be 1864]

Dear Cousins,

As I am ordered to keep awake tonight, I propose to spend a portion of thetime in writing although the circumstances are not the most favorable for such an undertaking. The fact is impressed upon my mind of having visited Fayetteville but it seems almost like a dream. The thoughts connected with it seem really too pleasant to have ever been realized. It is said that the great masters can never produce upon canvas the brightest pictures of their fancy; so my visit home seems to have been a work of the imagination.

There is one thing which I did not have time to tell you about which seems so strange that I will note it down here. I think I have mentioned before that while laying under the enemy’s guns at Fredericksburg with a prospect of being launched at any moment into eternity, I had a refreshing sleep and sweet dream of home. Another time when, Jacob like, I had only a rock for a pillow and the canopy of heaven for a covering (the rain pattering into my face broke the spell), I mingled once more in th family group around the fireside. But while at home, where externally everything was reversed, I dreamed of fierce battle and the field of strife.

I cannot thank you both enough for your kindness during my visit. You seemed to have anticipated my every wish and to have spared no pains to have them gratified. Having so many things to converse about, I omitted to express my gratitude although it was by no means unfelt. The many assurances of regard were very cheering, suggesting thoughts which are extremely pleasant in this isolated life. As to the the coming season, I have no anxiety but can trust in Him who has been my stay and protection in days that are past.

I was greeted very warmly at Clinton, and would like to have spent more time there had not my time of absence been so limited. I met sister Lucy and Adelbert at Utica who accompanied me to Quaker Street. I met Daniel there so that with the exception of Mary, all of [my] own brothers and sisters were there. It would be superfluous to add that I had an excellent visit.

I called on Edward Payson in New York and I hope I shall be able to get him the Chaplaincy of our regiment, but I had rather you would not mention it as it is very uncertain. I spent a few moments at cousin Norton’s and found them well. On Sunday I heard Beecher, as to whose orthodoxy I can now agree with you. Taking up the strain of the Universalists, his theme was principally love and charity. He contended that a deed of benevolence was a proof that there was so much God in the donor. I very much prefer the theology of Burns on this point, who says:

“The heart benevolent and kind

The most resembles God.”

Faith and repentance were left entirely in the background. The singing was fully in accordance with my idea of worship, and in fact, seemed the best part of the exercise.

Having some time in Washington, I visited the Capitol and had the privilege of hearing Senators Sumner, Doolittle, Johnson, and one or two others. Sumner’s remarks were quite lengthy and I had a fine opportunity to see and judge of the man. The question of taking the Oath was the subject of debate. Senator [James Alexander] McDougall of California was attracting considerable attention about town with his Mustang pony and Mexican hat (which evidently contained “a brick”). On the whole, his conduct was far from being creditable to a man in his position. 1

This morning I attended the funeral of one of the Captains of our Brigade who was drowned under exceedingly painful circumstances. He had applied for a leave of absence and was to have married Friday. His leave came two hours after his death. His father was a Baptist minister and what a shock it must be to his parents and intended wife. Although for some years an active member of the church, we have reason to fear that he was poorly prepared for the “Dark Beyond.”

You will perceive by the date that I am on duty again. The weather is as warm and pleasant as May and we have a full opportunity to enjoy it. It seems quite natural to be back here again among these with whom I have been so long associated. I am to remain out here two days. My quarters are very comfortable but as I mentioned before, there are no provisions here for writing letters.

As I received two months pay in Washington, I sent one hundred dollars by Express to you. I have looked over the account hastily and make it up to the first of January $515.47. This includes the twenty dollars which I wished to be reserved as I have forgotten the date that I notified you to that effect. As you probably have it, you can make the proper deduction and dispose of the remainder as suggested. I am receiving the New Yorker regularly. I expect to be on duty now nearly every day as three of the companies with their officers have been detached, two officers are away recruiting, and two absent on furlough. In spite of this reduction our duties have not been lessened.

The thought of home reminds me of some lines which I was so much pleased with that I took pains to copy them. [Line from poem not transcribed]

Affectionately, Henry

1 While serving in the U.S. Senate during the Civil War, McDougall worked on behalf of a Pacific railroad project, but alcohol abuse made him ineffective. By 1862, McDougall was making a spectacle of himself and neglected his Senate duties. He fought against some of Lincoln’s war measures, but he was mostly dysfunctional. Not once did he travel back to California during his entire six-year term. Upon leaving office, McDougall retired to his boyhood home in Albany, New York, where he died on September 3, 1867, presumably of alcoholism.

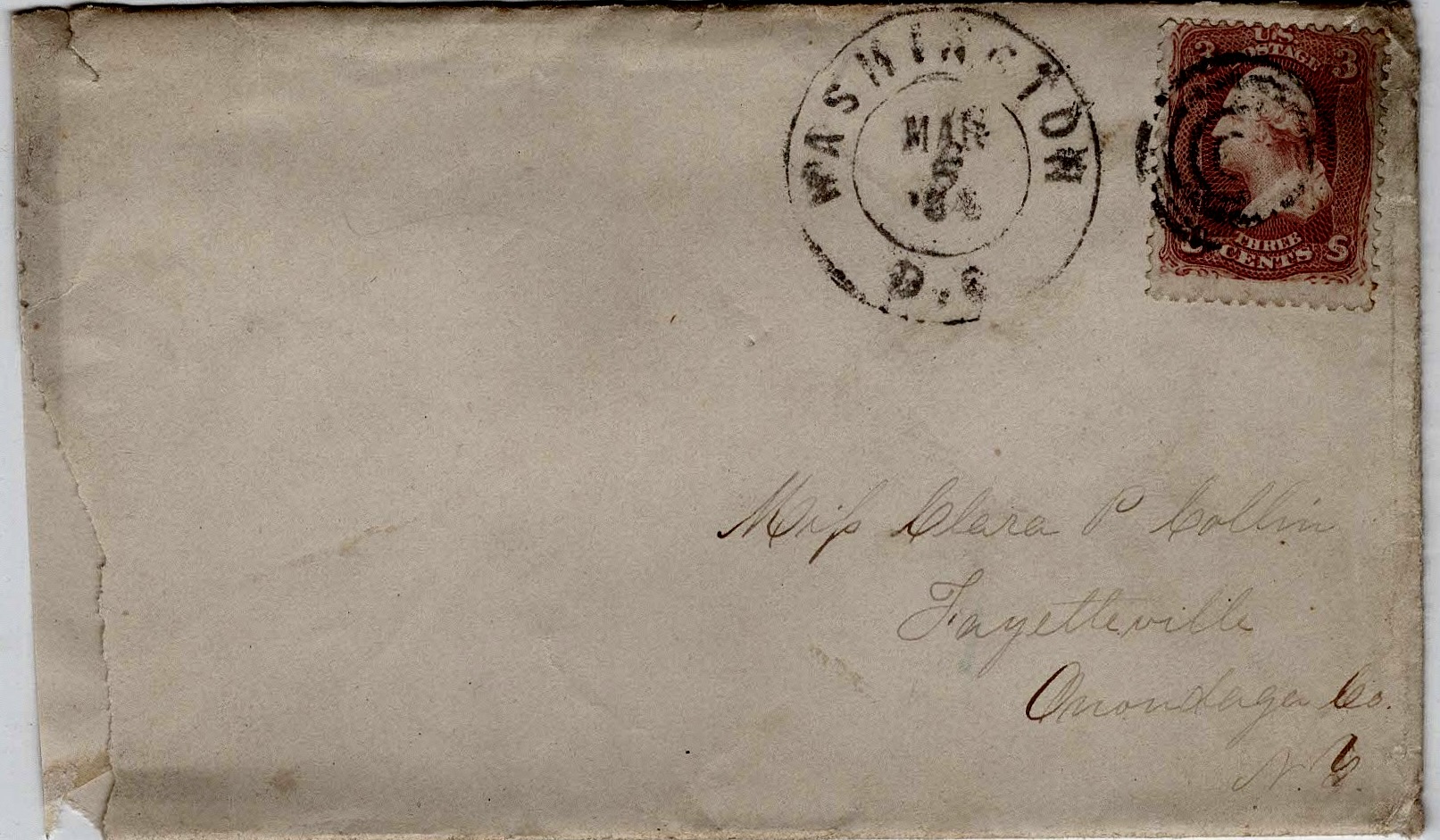

Letter 7

Warrenton Junction, Virginia

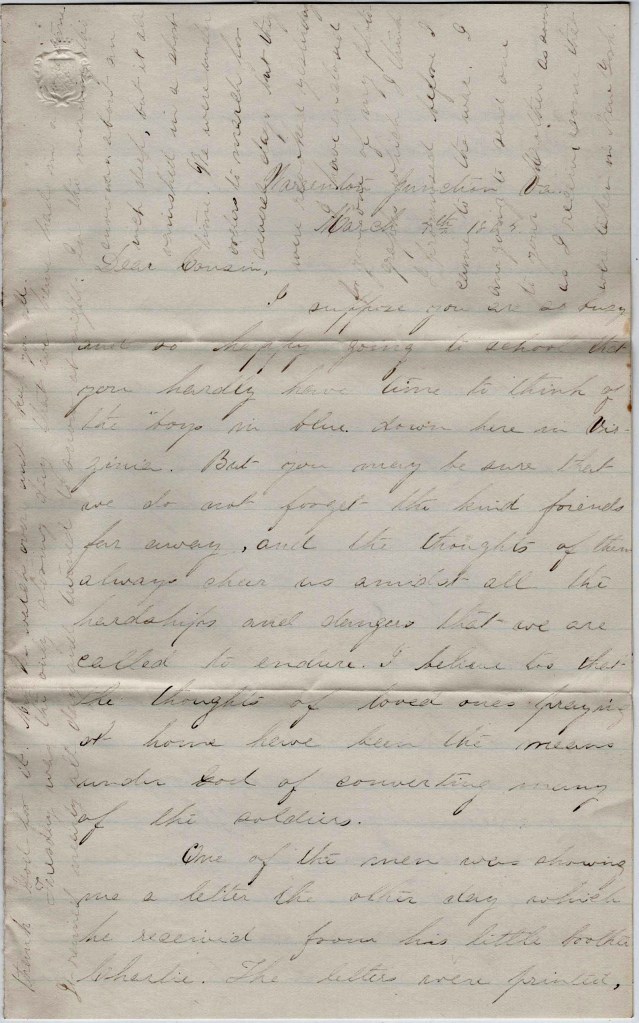

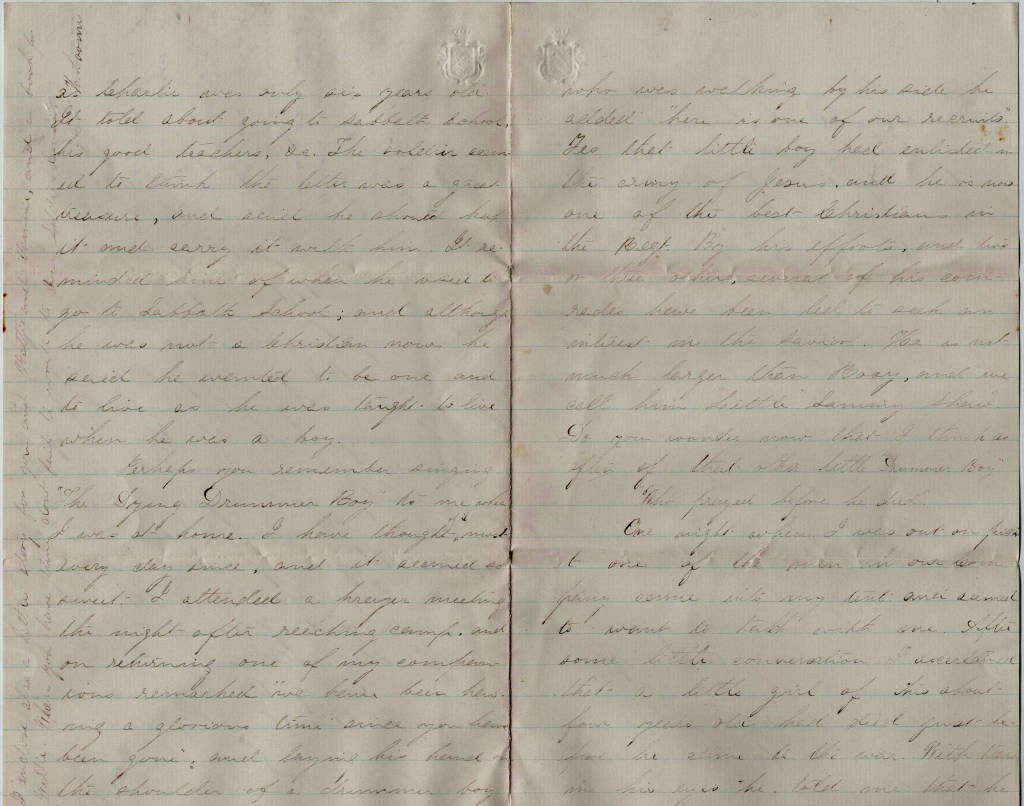

March 4, 1864

Dear Cousin,

I suppose you are so busy and so happy going to school that you hardly have time to think of the “boys” in blue down here in Virginia. But you may be sure that we do not forget the kind friends far away and the thoughts of of them always cheer us amidst all the hardships and dangers that we are called to endure. I believe too that the thoughts of loved ones praying at home have been the means under God of converting many of the soldiers.

One of the men was showing me a letter the other day which he received from his little brother Charlie. The letters were printed as Charlie was only six years old. It told about going to Sabbath school, his good teachers, &c. The soldier seemed to think the letter was a great treasure and said he should keep it and carry it with him. It reminded him of when he used to go to Sabbath school and although he was not a Christian now he said he wanted to be one and to live as he was taught to live when he was a boy.

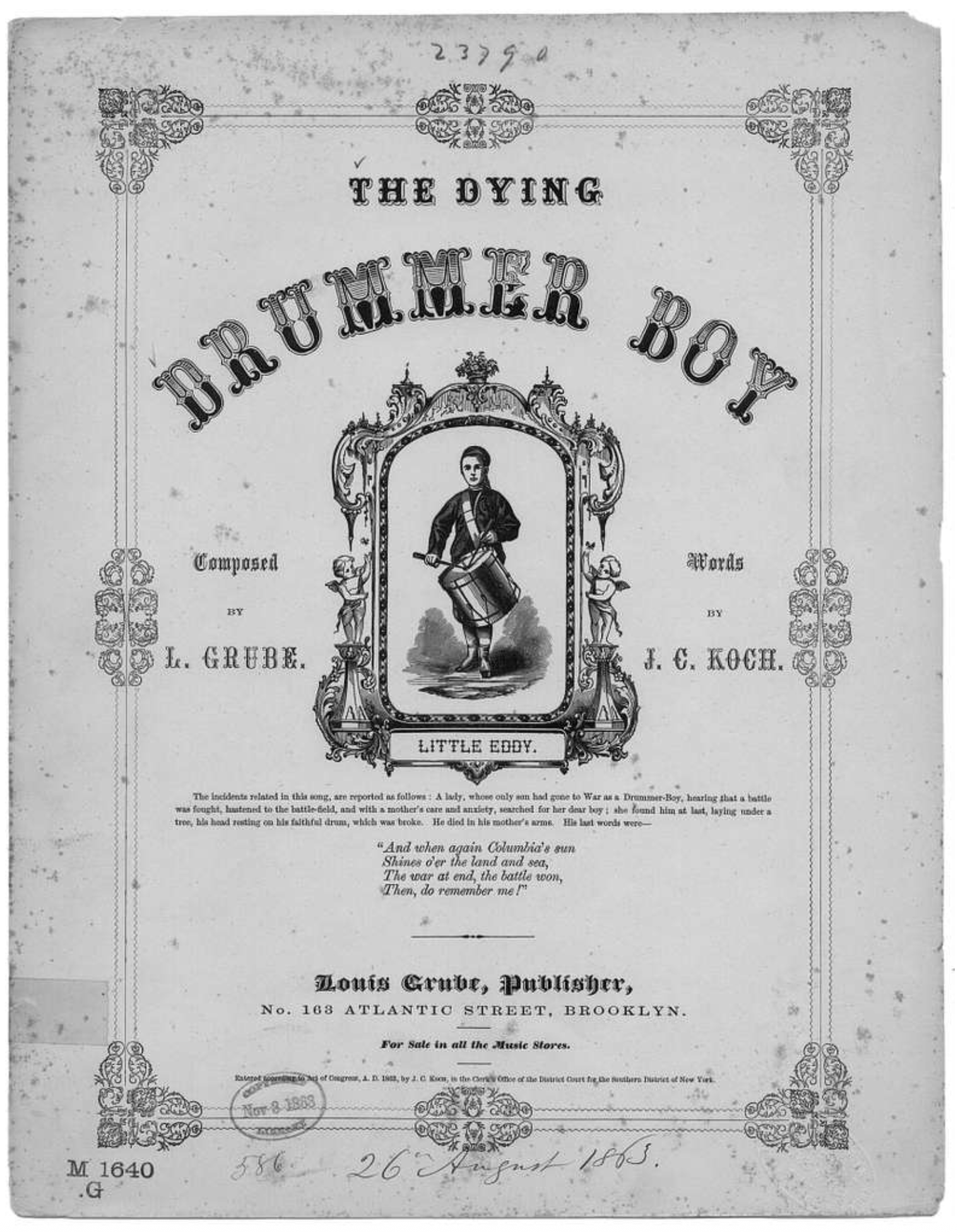

(Library of Congress)

Perhaps you remember singing “The Dying Drummer Boy” to me when I was at home. I have thought of it much every day since, and it seemed so sweet. I attended a prayer meeting the night after reaching camp and on returning one of my company remarked, “We have been having a glorious time since you have been gone.” And laying his hand on the shoulder of a drummer boy who was walking by his side, he added, “Here is one of our recruits,” Yes, that little boy had enlisted in the Army of Jesus and he is now one of the best Christians in the regiment. By his efforts and two or three others, several of his comrades have been led to such an interest in the Savior. He is not much larger than Rosy and we call him “Little Sammy Shaw.” 1 Do you wonder now that I think so often of that other little “Drummer Boy” who prayed before he died?

One night when I was out on picket, one of the men in our company came into my tent and seemed to want to talk with me. After some little conversation, I ascertained that a little girl of his about four years old had died just before he came to the war. With tears in his eyes, he told me that he had been thinking about her ever since and he wanted to become a Christian now so that he would be ready to meet his dear Minnie in Heaven. Although he did not go to meetings before, he had been very willing to attend since and we are hopeful that he will give his heart to Jesus and be ready to meet his darling never more to be parted.

The interest in our meetings has been continually increasing. The Chapel and Christian Commission tent are filled every evening. Mr. Hatter [?] (who preaches in the Brigade Chapel) told me this morning that he had been busy every afternoon this week conversing with inquiries. On Tuesday evening there were about twenty at the depot who remained after meeting for the purpose of conversation. Tis a good work and we thank God for it. May He watch over and keep you all. Tuesday was the only stormy day that we have had in a long time. It rained nearly all day and turned to snow at night. In the morning the snow was about an inch deep but it all vanished in a short time.

We were under orders to march for several days but they were revoked yesterday. I have enclosed for you one of my photographs which I think I promised before I came to the war. I am going to send one to your Mother as soon as I receive some that were taken in New York. I enclose also a little story for you and Hattie and Minnie, and a book for Willie. When you have time, don’t fail to write to your soldier cousin, — H. Loomis

1 “Little Sammy Shaw” must have been James Shaw who claimed to be 16 years old (actually only 14 or 15) when he enlisted as a musician in Co. C at Utica on 10 October 1862. He mustered out with the company on 16 July 1865 at Washington D. C. I believe he was the son of Sidney R. Shaw (1822-1863) and his wife Sarah J. (b. 1825 in Ireland). I cannot account for Henry calling him Sammy unless it was because he forgot the name or it was Shaw’s middle name.

Letter 8

Camp near Petersburg, Va,

July 7th 1864

Dear Cousin,

At length we have had a rest. A week ago Tuesday we were relieved from the sandy pit in which my last was written, and placed on reserve. After eleven days of such experience, there is an enjoyment of rest and quiet which persons in civil life will hardly appreciate. But rest and quiet with us is comparative. Nearly every moment has been occupied in making out Muster Rolls and returns of various kinds. And quiet consisted in listening to the crack of rifles and “the music of the spheres” without any fear of being harmed thereby.

Although it is now nearly nine oclock at night the pickets are still at work, and the intervals between the reports are numbered by only a few seconds. I presume it will be the same all night as it has been so for nearly three weeks past.

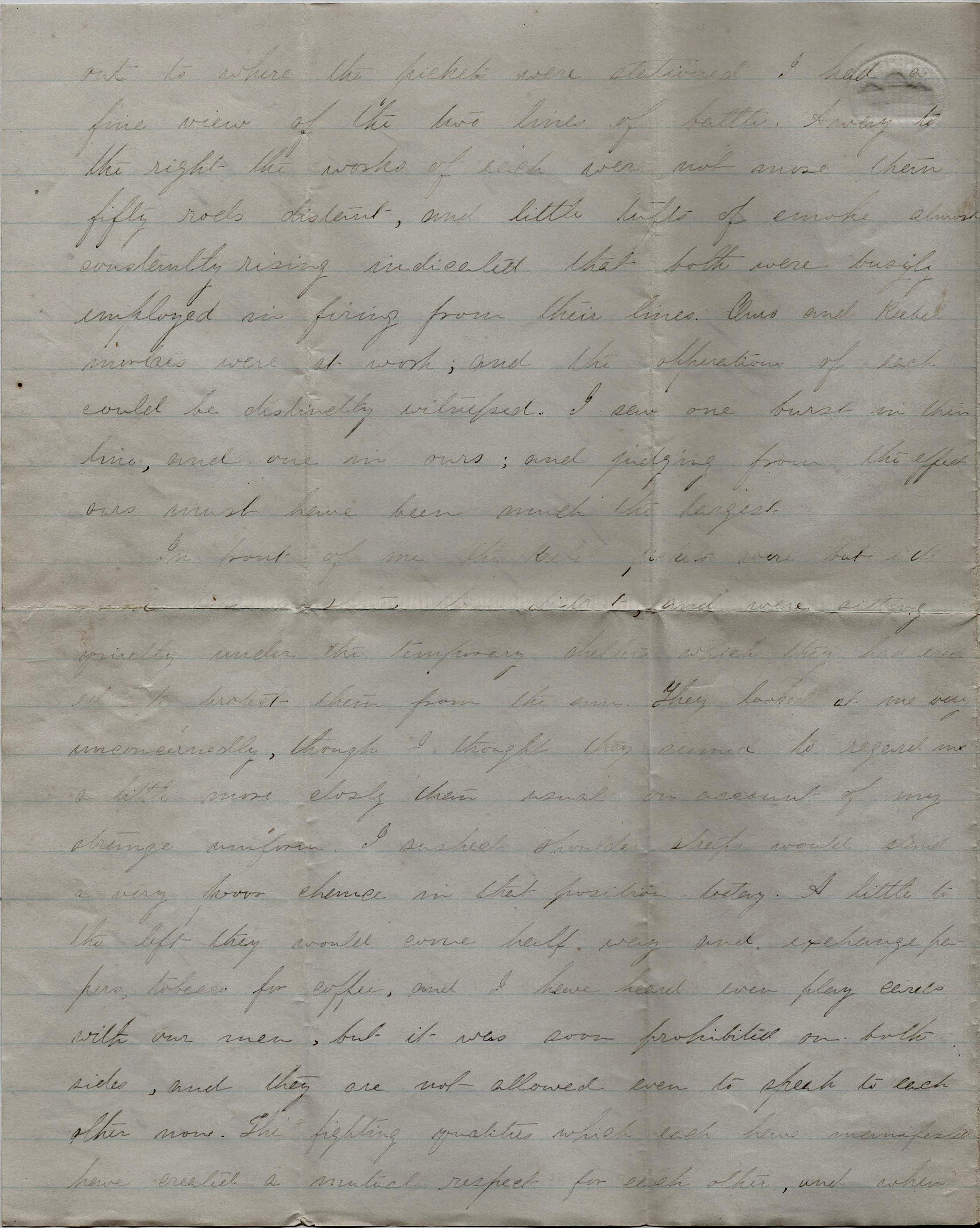

This last remark refers more particularly to the right of our line. Soon after we were relieved there was a mutual agreement to cease firing at that point and until yesterday it was perfectly quiet. I took a walk out in that direction the day before, and going out to where the pickets were stationed, I had a fine view of the two lines of battle. Away to the right the works of each were not more than fifty rods distant, and little tufts of smoke almost constantly rising indicated that both were busily employed in firing from their lines. Ours and Rebel mortars were at work and the operations of each could be distinctly witnessed. I saw one burst in their line, and one in ours; and judging from the effect ours must have been much the largest.

In front of me the Rebel pickets were but little more than a stones throw distant, and were sitting quietly under the temporary shelter which they had erected to protect them from the sun. They looked at me very unconcernedly, though I thought they seemed to regard me a little more closely than usual on account of my strange uniform. I suspect shoulder straps would stand a very poor chance in that position today. A little to the left they would come half way and exchange papers, tobacco for coffee, and I have heard even play cards with our men, but it was soon prohibited on both sides, and they are not allowed even to speak to each other now.

The fighting qualities which each have manifested have created a mutual respect for each other, and when permitted to meet, they are like old friends instead of foemen, If our prisoners were under the charge of old soldiers instead of raw militia, their treatment would be far less severe. I had rather be guarded three months by the soldiers of Lee’s army than one month by those who have never been in the field. One of the 44th New York who was captured at Spotsylvania and retaken by Gen. Custer told me that the Provost Guard would divide their rations with our men, although they were themselves short at that time. By the way, the guard belonged to the 10th Virginia Regiment whose Colonel and Major were killed in the charge which was made by us on the 5th of May.

I believe the fighting on the 16th of June has done as much for our cause as any other battle of the campaign. It demonstrated to a certainty that the negroes can and will fight. Their conduct on that occasion has been the theme of converse ever since. It was sickening before to hear the ignorant and unthinking repeat the sneers and insinuations of Northern Copperheads. From the same ones you now hear, “Bully for the Niggers!” and so it is the same through the whole army. It will make a soldier mad now to tell him the negro won’t fight. Henceforth he will be regarded as a companion in arms, and to deprive him of his blood bought laurels would be an injustice to all. Their soldierly bearing and superb deportment is remarked by all who have ever seen them.

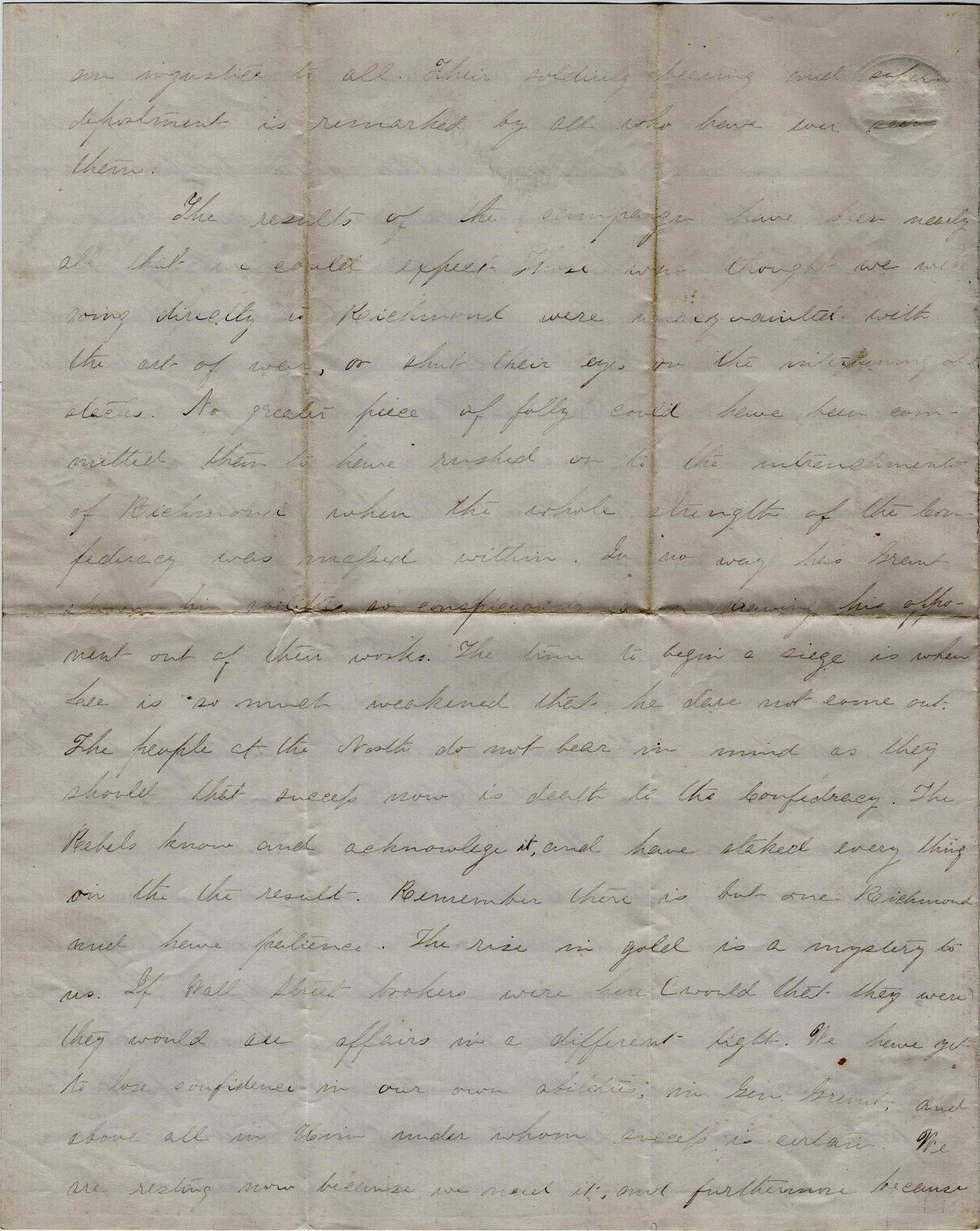

The results of the campaign have been nearly all that we could expect. Those who thought we were going directly to Richmond were unacquainted with the art of war, or shut their eyes on the interfering obstacles. No greater piece of folly could have been committed than to have rushed on to the entrenchments of Richmond when the whole strength of the Confederacy was massed within. In no way has Grant shown his abilities so conspicuously in drawing his opponent out of their works. The time to begin a siege is when Lee is so much weakened that he dare not come out. The people at the North do not bear in mind as they should that success now is death to the Confederacy. The Rebels know and acknowledge it, and have staked everything on the result. Remember there is but one Richmond and have patience.

The rise in gold is a mystery to us. If Wall Street brokers were here (would that they were), they would see affairs in a different light. We have yet to lose confidence in our own abilities, in Gen. Grant, and above all in Him under whom success is certain. We are resting now because we need it and furthermore because we have earned it. Tis not all rest however. Though not heralded in the papers, every day is telling on the Confederacy.

We are encamped a little more than half a mile in the rear of the front line/ Being in the woods, we are as comfortable as could be expected at this season of the year. Although it is very sultry, there is generally a cool breeze during the day. As there has been no rain in more than a month. the dust is now supreme where the mud has been universally conceded to hold sway. Streams have long since ceased to exist and we can only get supplies of water by digging wells. By going down from five to twenty feet we get a very good article. The one from which our regiment is supplied is about eight feet in depth. Considering the season and what we have endured, the health of the men is excellent. I think only about one in twenty of our men is reported sick and these are mostly cases of the diarrhea. The increase in the quantity and quality of the food since we reached here is working wonders in the improvement of the army. In sending supplies of onions, the Sanitary Commission have acted wisely. Nothing would be more beneficial or acceptable. Sutlers supplies are now plenty also.

For the past two days the newsboys have sold all their papers before reaching here so that we are ignorant of what is going on in Maryland. I am heartily glad that the Rebels are trying to divert us from here. If the troops which have gone from here are properly reinforced. that army will rue the day they ever crossed the Potomac. I only wish we had the whole of Lee’s army in Pennsylvania or Maryland. There is a marked difference between aggressive and defensive fighting. Nothing would rejoice the army more than to meet the Rebels on fair ground. Gettysburg tells what we can do even when far inferior. With an equal or superior number, the result can be surmised.

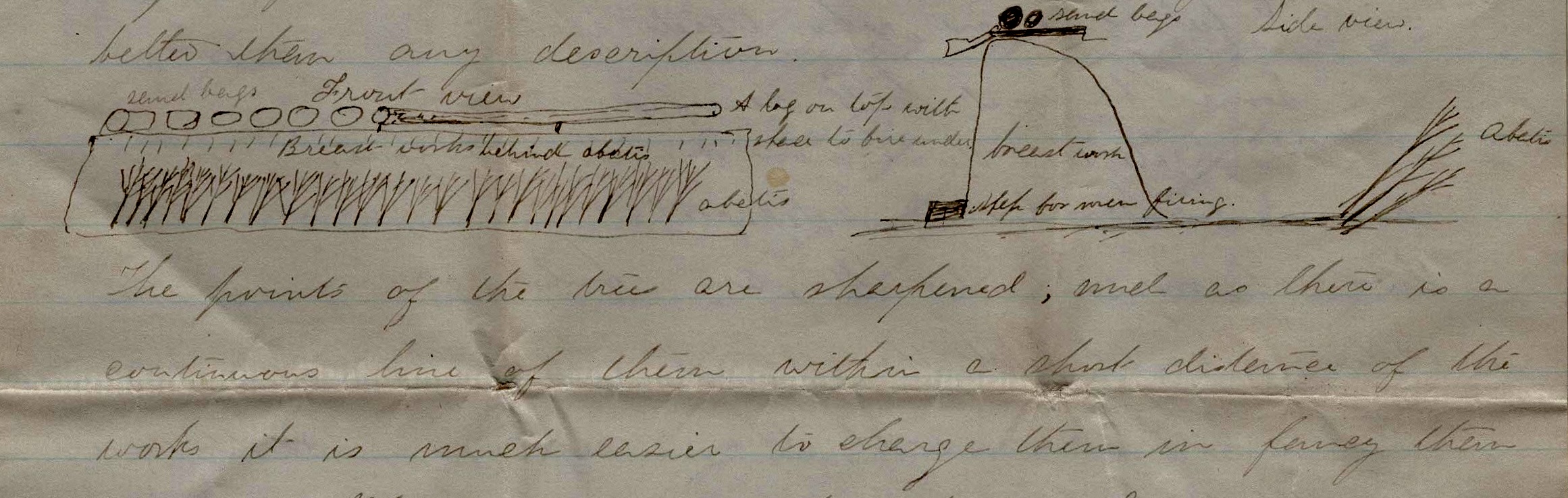

July 8th 1864 It is much more quiet today than yesterday. The picket firing was kept up very briskly during the night but has ceased almost entirely today. There is an occasional rifle shot and boom of cannon but much less frequently than usual. I think we shall remain here some time and probably without much fighting, yet we may leave before night. Present appearances seem to indicate that we are to remain on the reserve and certainly we shall not object. We have been continually gaining ground upon the right and shall probably push the enemy back to Petersburg. As the Rebels have strong works, it will of necessity be a work of time. They as well as ourselves place an abatis in front of their line which are very pleasant to be behind, but uncomfortable to come in contact with. An abatis consists of trees from three to six inches in diameter, placed close together in the ground at an angle of about 25 or 300.

A rude sketch may illustrate better than any description. The points of the tree are sharpened and as there is a continuous line of them within a short distance of the works. It is much easier to charge them in fancy than in reality. While charging on the 18th ult. I ran into several holes which had been bored into the ground by an instrument for setting posts. As there is nothing but sand here, it can be used to great advantage. The depth of the excavation was about four feet and they were just large enough to admit one foot.

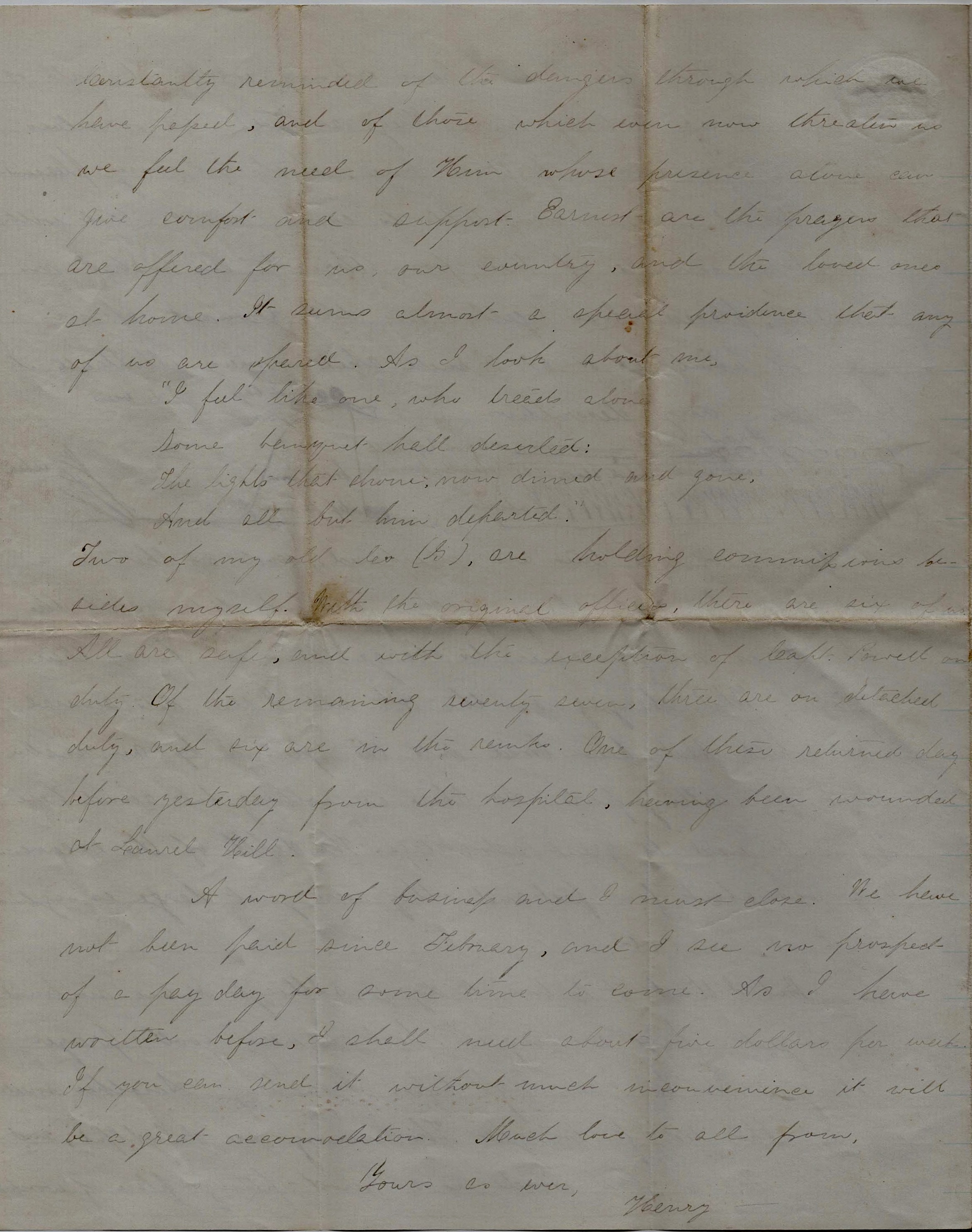

But I think it is time to digress although I see no limit to the subject. Last evening we had a very good prayer meeting and two evenings before preaching. Another meeting is appointed for tonight. The evenings are delightful and a quiet spot in the woods is a most fitting place of worship. Constantly reminded of the dangers through which we have passed and of those which even now threaten us, we feel the need of Him whose presence alone can give comfort and support. Earnest are the prayers that are offered for us, our country, and the loved ones at home. It seems almost a special providence that any of us are spared. As I look about me,

“I feel like one who treads alone

Some banquet hall deserted

The lights that shone now dimmed and gone

And all but Him departed.”

Two of my old Co. G are holding commissions besides myself with the original officers. There are six of us. All are safe and with the exception of Capt. Powell on duty. Of the remaining 77, three are on detached duty and six are in the ranks. One of these returned day before yesterday from the hospital, having been wounded at Laurel Hill.

A word of business and I must close. We have not been paid since February and I see no prospect of a pay day for some time to come. As I have written before, I shall need about five dollars per week. If you can send it without much inconvenience, it will be a great accommodation. Much love to all. From yours as ever, — Henry

Letter 9

Yellow House [Globe Tavern], Virginia

August 24, 1864

Dear Cousin and Friend,

Tonight completes another year of a soldiers life. Having written to you a year ago today, I propose to address to you another annual letter, grateful to Him whose care I have enjoyed and whose presence has saves me in every dark and perilous hour. I thought I had seen it all then, but a later experience has shown me that at that time I did not know what war was.

I am writing in a merely temporary shelter, with a warning to be ready to move at any moment. In the direction of Petersburg there is an almost constant booming of cannon and mortars, and what may be the result, or object, we know not. It is hardly to be supposed that the Rebels will permit us to hold so important a point without another effort to dislodge us. But we are well prepared here; and they will be very loth to repeat the sacrifice of Sunday the 21st.

In the battle of the 18th [see Battle of Weldon Railroad], our regiment was deployed as skirmishers, and as soon as the Rebels were repulsed, Lieut. [Arthur V.] Coan and myself were sent forward again with what portion of our regiment had rallied. Being senior to him, I was for a time in command. We were together most of the time, and I had left him but a few moments when a stray ball passed through his breast, inflicting a serious if not fatal wound. He was a member of Co. G and succeeded me as Orderly. On the same day, Capt. Stewart was taken prisoner. We were on the line together, when a part of it was driven back and he probably walked into the enemy’s lines supposing that he was still within our own.

The next morning we found that the Rebels had fallen back and we that were on picket were ordered forward to ascertain their position. We found in doing so that only their own wounded had been removed, leaving all the dead and our wounded still on the field. Such is war. Nor will I attempt to describe the pictures.

About five in the afternoon, the Rebels advanced upon us in two lines of battle. Amid a shower of bullets, we made our way back to the line. Here we found the Third Division (Crawford’s) had been flanked, and in a short time nearly the whole line gave way and started for the rear. It seemed then that everything was lost; and so it would have been had it not been for the best of Generals, Ayres, Griffin, and Warren. Our lines were quickly formed while the artillery kept the enemy at bay. This being done, we moved forward and retook our old position. We moved on Saturday night and a new line established. Early the next morning the Rebel batteries opened upon us from two sides. We were moved into some breastworks, but it was some time before we could decide which way was the front as the shells swept both sides alike. It may seem strange, but there were many jokes and some laughter, as we jumped back and forth for shelter. Had their fuses been good we would have suffered terribly, and perhaps the whole result would have been changed. But it was Sunday work, and as ever, God frowned upon it.

How the Rebels came out of the woods and found they were deceived as to our position. How they were swept down by our canister and musketry. How they made signs of surrender and then escaped, you have already learned from the papers. Seventeen North Carolinians came into our lines in front of our regiment, glad of an opportunity to desert. I think as many more were killed of the same squad before their object was known to us. It is by no means an unimportant fact that there were gray-haired men and even boys among the number. As I have said before, the North has yet to learn the meaning of the word sacrifice.

Of the thirteen lieutenants who left Warrenton Junction, but two of us are left. Being in command of two companies, I have less time to myself than heretofore. Day after tomorrow is Muster Day & and to prepare eight Muster and Pay rolls is a work of no small difficulty or importance.

September 2nd. I had not finished the last sentence when orders came to pack up immediately and be ready for action. Some musketry was heard in the direction of Petersburg and soon the news comes in that the Rebels had charged on a signal station and the [W. W.] Davis House and captured several of our men. The latter place is on the Weldon Railroad and about three miles distant from Petersburg. This movement of the enemy was supposed to be preliminary to a general attack. As our forts were not then completed, their chances were much better then than now.

The same night I was sent out on picket for three days. I was stationed at the Davis house which was the extreme outpost and the scene of the trouble in the morning. Early the next day I saw the Rebels coming down that track and in a few moments the bullets were flying thickly, and my squad of twenty-five were replying as best they could. After an hour and a half of such work, a newspaper was waved by them, and two of their number throwing off their accoutrements, came down to where we were wishing to exchange papers and establish a truce. I agreed to cease firing but would not exchange until conferring with my superiors. Having obtained a paper and permission, I started out to find my late visitors, but they had fallen back nearly three-fourths of a mile.

Reaching their advanced post, I requested an interview with their commanding officer. Presently Maj. Worden of the 16th North Carolina Regiment came down the track, accompanied by Capt. Malone—a Rebel Quarter Master. 1 He extended his hand with a “Good morning, Lieutenant,” and as I grasped it and looked into that generous, manly face, it hardly seemed possible that it was such men we were fighting. He was about thirty years of age, full six feet in height, and a perfect picture of health and strength. In his manners and conversation, he was a gentleman, yet under the circumstances it was a little difficult to occupy the whole time in conversing. Of course both wished to obtain information which neither were willing to give. As near as I can remember we conversed as follows, having first been requested to take a seat by his side in the shade.

Maj. W: “What is the news this morning?”

Lieut. L: “Nothing. Have you any?”

M: “No, we always get it from your papers. Have you a paper to exchange?”

L: “Yes” (I then looked at the one furnished me and found the date to be Aug.. 23, and so I could not fairly ask for an exchange. he still kept his of Sept. lst in his hand. I then apologized as I had not examined the date before but supposed it to be the last.)

M: “What Corps do you belong to?”

L: “Fifth. What is yours?”

M: “Hills Corps, Hokes Division. Who commands your Corps.”

L: “Genreal Warren.”

M: “I think I like our manner of designating the Corps better than yours. Ours are known by the names of their commanders, as Hills Corps, Mahone’s Division, Archers Brigade.”

L: “But the frequent change of commanders renders such a system objectionable.”

M: “Yes, but for a time the old name can be added.”

L: “Your men requested a cessation of picket firing. Does it meet with your approval?”

M: “Certainly. Picket firing is simply murder, but should either line advance of course this agreement is at an end. I wish we might stop the whole fighting as easily.”

L: “Were you at Reams Station the other day?”

M: ” Yes, and a hot time we had of it too!”

L: “Then your loss was heavy?”

M: “Yes it was.”

L: “I see you wear the badge of our Second Corps.”

M: (blushing) “Yes, one of my men got this hat off a prisoner the other day.”

A lieutenant of the 5th N.Y. being introduced, remarked that it was a pleasant day. “Yes,” replied the Major, “too pleasant for such work.”

We passed nearly an hour conversing in this manner when with another shake of the hand and a mutual desire to meet under more favorable circumstances we separated. The Major wore a shabby dress coat of blueish gray, with two rows of buttons in front, and a lace star on his collar to designate his rank. His pants were blue, like those which our privates wear, and I should judge the same. His shoes were coarse and of English make. His neck tie was of cotton and very much faded. Both his hat and buckskin gloves were of very ordinary material. Such was the outward man such in part the interview. I cannot think him treacherous, yet what I have yet to narrate shows there was a lack of honor somewhere.

I met the Rebels twice afterwards during the day; bought a couple of papers and engaged some for the next morning. One of them I sent home. A brother of Gen. Warren and a Captain on his staff were out with me once. Early in the morning following. I was relieved by Lieut. [Charles L.] Buckingham [of Co. B] in order that I might make out my Muster Rolls. Scarcely an hour had elapsed before word was brought that he had been shot. He had gone out to get my papers and some for himself when some South Carolinians it is supposed got in his rear and, as he returned, shot him through the body. He escaped however but died the same day. 2 He was wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness and had joined the regiment but two days before. Thus they have fallen, yet God has spared me. Why I know not but I will try to do my duty and when missing here, I trust I shall answer “aye” at the heavenly roll call.

I look back over the past two years with no regret that I have chosen such a life. It has been a season fruitful of experience yet still more rich in mercies. We of the army are not discouraged. We can see progress and not far in the distance a glorious end. In the thought of what is to be accomplished, we forget our present toils and dangers. It is not ease or luxury that gives enjoyment, but “the path of duty is the path of peace.” I love not my friends and home less, but in peaceful days shall enjoy them more. Thank God for the & victories at Mobile Bay and Atlanta. May the days of peace be thus hastened is the prayer of your soldier cousin, — Henry Loomis

P. S. We are now well fortified here and can hold this position against almost any force. We have now in our regiment a Major, two Captains and two Lieutenants (one Lieutenant is absent on leave and due tomorrow). The Major has command of the regiment and we four have the rest of the wash to do. I think we shall remain here some time; perhaps be assigned to hold this position. Col. Stone (formerly Gen. Stone of Balls Bluff fame) commands our Brigade… I enclose a flower from the battle field. — H. L.

1 I cannot find a Major Worden in the 16th North Carolina Infantry; neither can I find a Capt. Malone as a Quartermaster in the Confederate army.

2 “Lieut. Charles Levi Buckingham, a graduate of the Class of ’62, Hamilton College, and an officer of the 146th Regiment, N. Y. V., died in the service of his country on Monday, Sept. 5th. He had but just reached his command, and while upon picket duty was returning from an exchange of papers with a rebel officer, when a party of the enemy from an ambush fired upon him, inflicting a wound from which he died. The hearts of all who knew him are chilled by the sad news. Charley Buckingham as a collegiate ever excelled. An accurate and faithful scholar, a polished and brilliant orator, the successful winner of the “Clark Prize” over competitors, as those of us have reason to know, of splendid attainments; the genial companion and pride of his classmates and friends. As a soldier he discharged his duties well, receiving in the battle of the Wilderness a honorable wound, from the effects of which he had hardly recovered, when the last fatal bullet cut short his young life.”

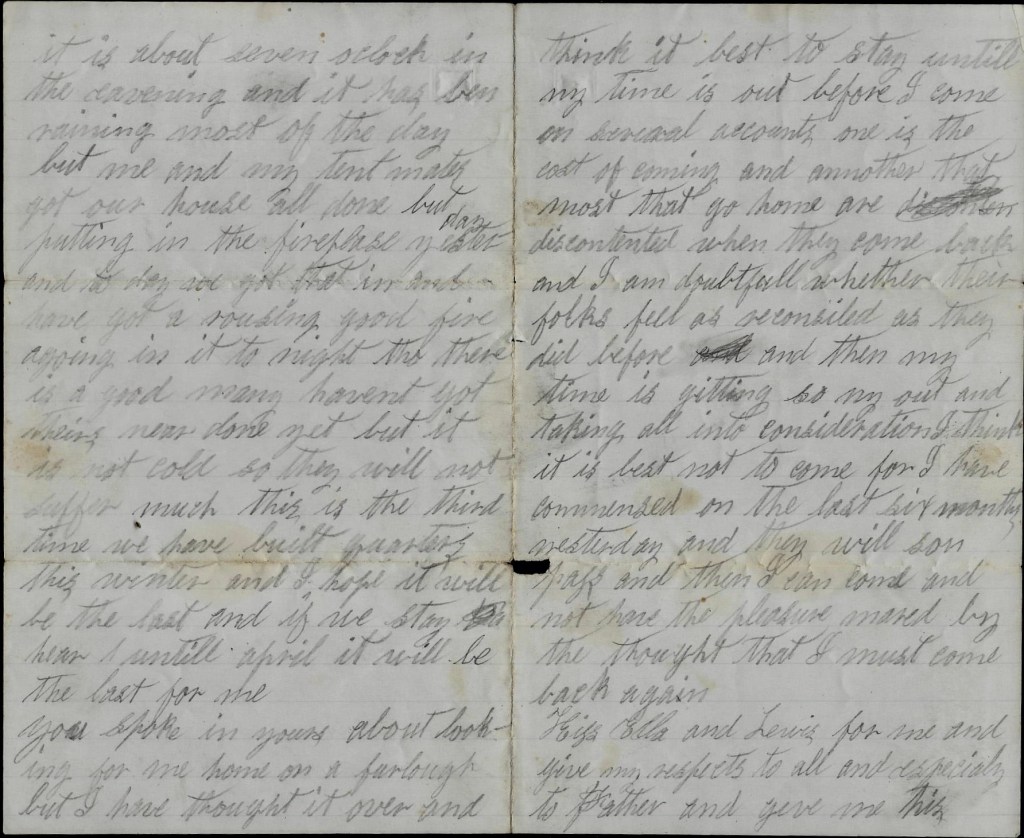

Letter 10

Camp near Hatcher’s Run, Virginia

March 28th 1865

Dear Cousin,

We were not engaged in the fight on Saturday but expected that we should be as we were moved up as a support. The campaign seems to have fairly opened. We expect to move tomorrow morning for some point at present unknown, and in all probability we shall strike another blow at the rebellion.

You will see from the enclosed letter that I have cancelled my indebtedness to the Educational Society. My health is very good, It is fine weather but there is the appearance of rain soon. The mail is waiting for me and I must close. Sending a present to Willie. Goodbye all. God bless you. — Henry

Letter 11

Camp on Arlington Heights, Va.

May 26th 1865

Dear Cousin,

Mary’s letter containing twenty-five dollars reached me last night. It was very welcome as it is quite expensive living here. Our camp is but a short distance from the one we occupied in October/November 1862. We have a fine view from here of Washington, the Potomac, and surrounding scenery. I have not been to the city yet as we have so many papers to attend to.

We were expecting to be mustered out at once, but from present indications it may be some time before we are released from the service. We have had no orders as yet as to what is to be done. Most everyone is hoping to be mustered out soon.

I went over to the Freedman’s Village last Sabbath and enjoyed my visit there very much. There was a Temperance Meeting for the colored children, and seventy of them signed the pledge. The children appeared much better than could be expected from those who had been subject to such treatment. They sang very well. In the afternoon a colored chaplain preached a sermon which would compare in every respect with some of the ablest preachers. I was fortunate enough to meet Mr. [H. E.] Simmons, the Principal, who showed me about the place and made it much more interesting. I think I shall go down and visit the school if we remain here much longer.

If we are not to be mustered out before long, I think I will apply for a leave. I have only one company now to attend to and I can get away much better than heretofore. I enclose a memento for your father. I am going to send your mother a little book made from the tree under which Gen. Lee surrendered but I have not finished it yet.

We have not seen Mr. Erdman yet. I suppose their regiment is somewhere about here but I do not know where. It is a very warm day and I am not in much of a mood for writing letters. Love to all, from cousin Henry

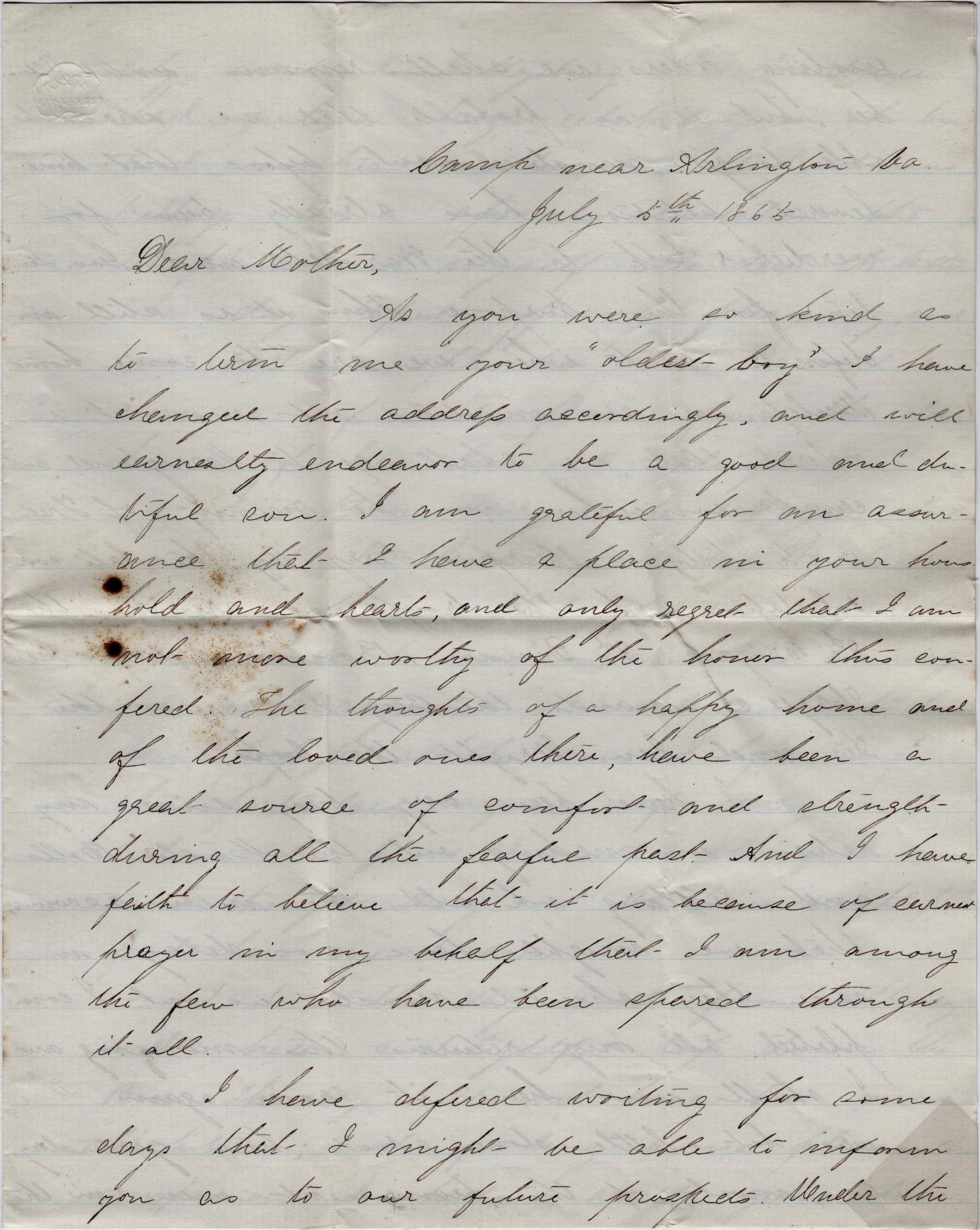

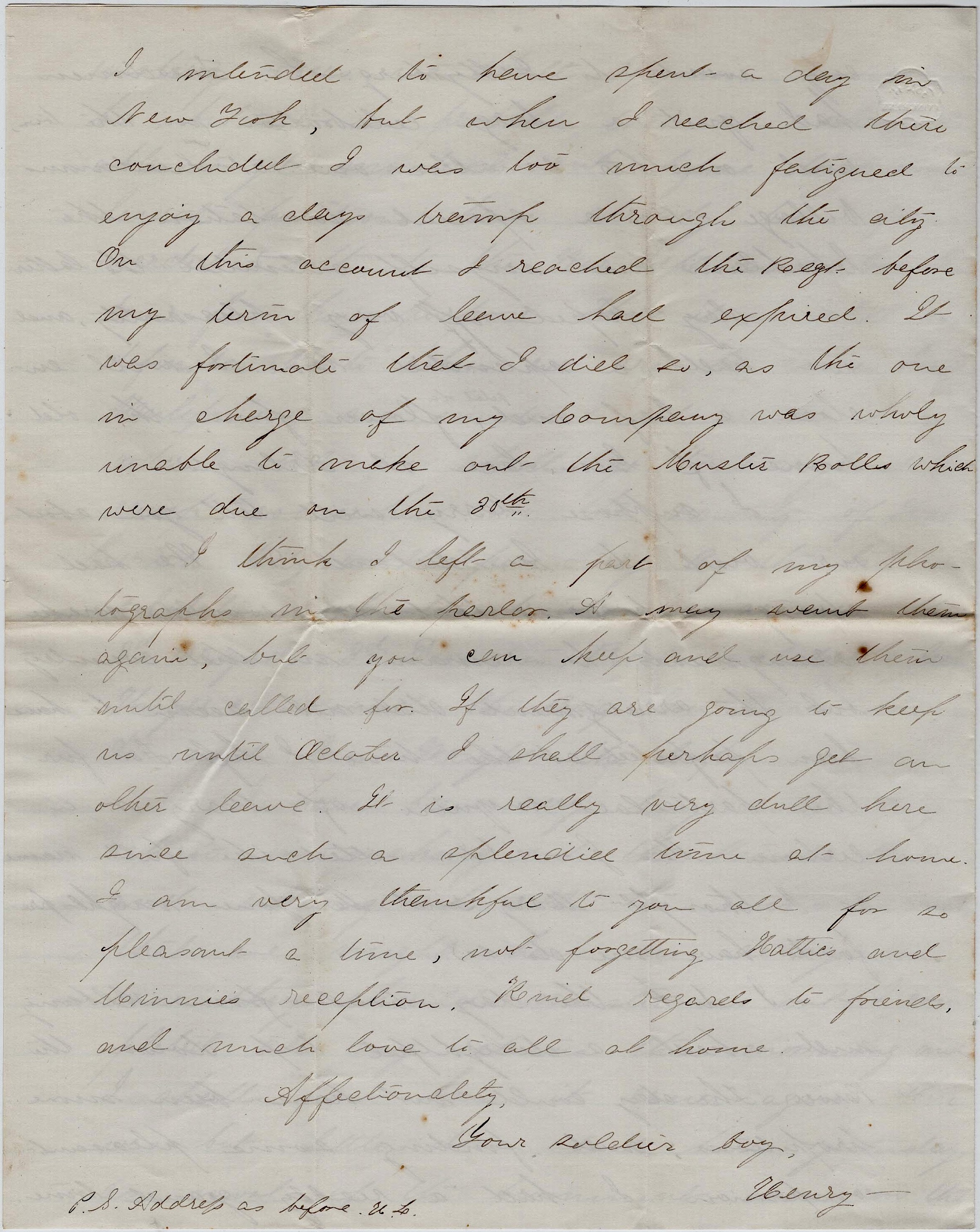

Letter 12

Camp near Arlington, Virginia

July 5, 1865

Dear Mother,

As you were so kind as to term me your “oldest boy,” I have changed the address accordingly and will earnestly endeavor to be a good and dutiful son. I am grateful for an assurance that I have a place in your household and hearts, and only regret that I am not more worthy of the honor thus conferred. The thoughts of a happy home and of the loved ones there have been a great source of comfort and strength during all the fearful past and I have faith to believe that it is because of earnest prayer in my behalf that I am among the few who have been spared through it all.

I have deferred writing for some days that I might be able to inform you as to our future prospects. Under the existing orders we shall remain until October but it is probable that we shall be able to get mustered out before that time. Several petitions have already been worded (both to the War Department and Gov. Fenton) for this purpose. Thus it is still indefinite as to when we are to come home. Unless we are mustered out soon, it is ordered that we shall go to Maryland and camp somewhere in the vicinity of Frederick City or Harpers Ferry. By the late consolidation of the troops, we are in the 3rd Brigade, 3rd Division, Provisional Corps. Gen. Hayes commands the Brigade. Gen. Ayres the Division and Gen. Wright the Corps.

I have been very bust since my return in making out the muster rolls and settling up all the men’s accounts that we might have no delay in case they should muster us out. I completed all my returns this morning and I shall now have it easier again. There was but little done about here yesterday as most of the prominent men in the city went to Gettysburg. The Freedmen had quite a large celebration in the town and another smaller one at Freedmen’s Village. By a special invitation the Chaplain and myself attended the latter. The day passed off very pleasantly and we had a splendid time. I will enclose a leaf and petal of a flower from the old home of Gen. Lee at Arlington.

I suppose Mary will tell you about our visit to Guildrland &c. We had strong suspicions that she would make arrangements to remain in that country but the arrangements did not seem to have been perfected at the time I left. For further particulars, inquire of Mary or a certain Mr. G—s. (I omitted the full name as I though Mary and Mr. Jones might prefer to have me do so.)

I took the day boat from Albany and had a delightful trip down the [Hudson] River. The day could not have been more propitious, and finding some pleasant companion, I had a really grand time. I intended to have spent a day in New York but when I reached there, concluded I was too much fatigued to enjoy a day’s tramp through the city. On this account, I reached the regiment before my term of leave had expired. It was fortunate that I did so, as the one in charge of my company was wholly unable to make out the muster rolls which were due on the 30th.

I think I left a part of my photographs in the parlor. I may want them again, but you can keep and use them until called for. If they are going to keep us until October, I shall probably get another leave. It is really very dull here since such a splendid time at home. I am very thankful to you all for so pleasant a time, not forgetting Hattie and Minnie’s reception. Kind regards to friends and much love to all at home. Affectionately, your soldier boy, – Henry

P. S. Address as before. — H. L.