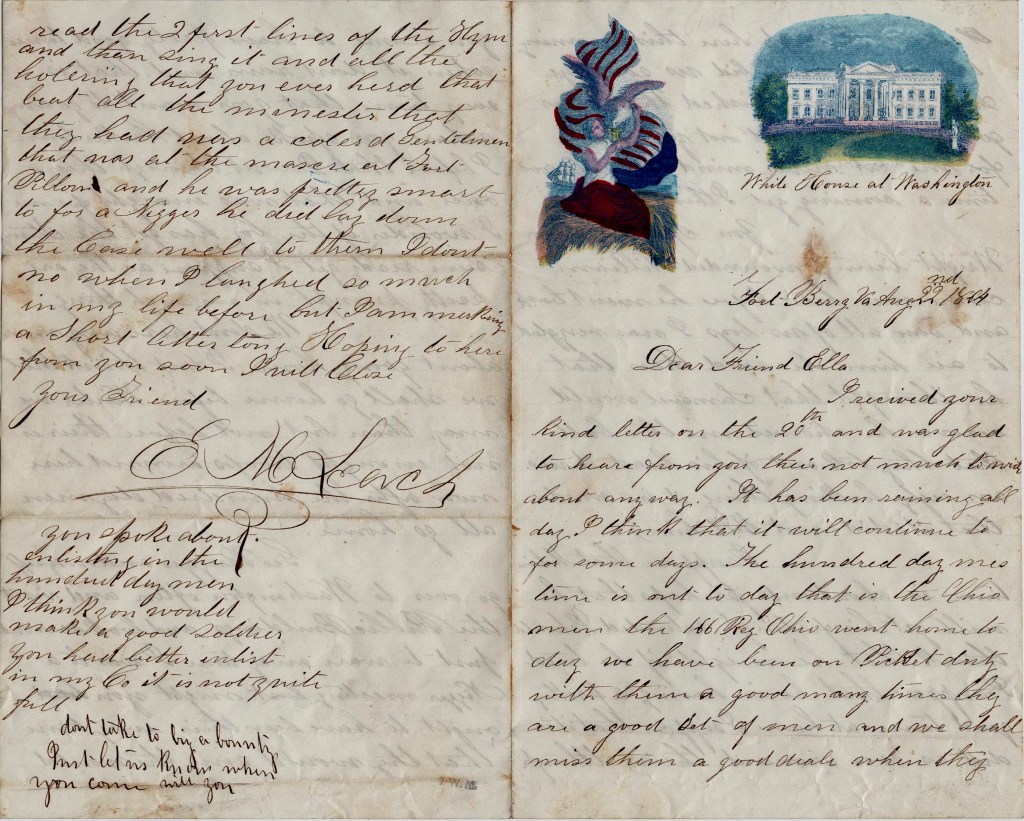

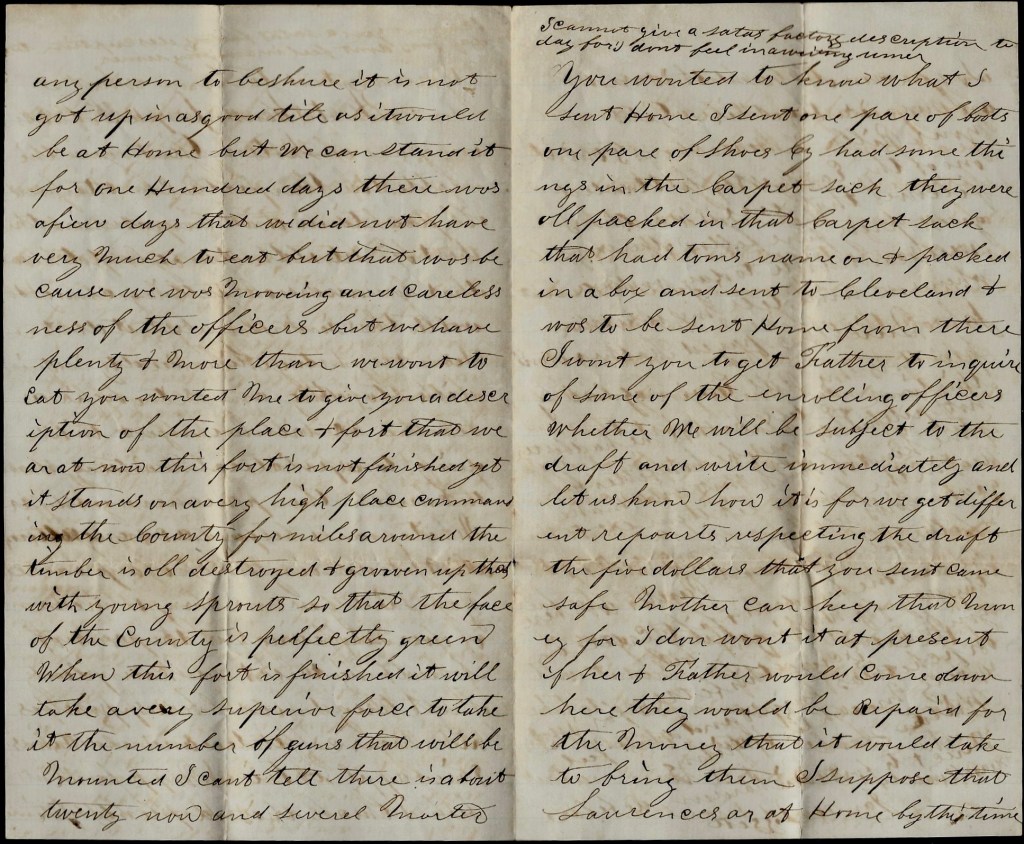

The following letter was written by Edmond Quincy Marion Leach (1847-1917) of Plympton, Plymouth county, Massachusetts who served in Co. A, 3rd Massachusetts Heavy Artillery. He began his service in December 1862 as a private and mustered out as a sergeant in January 1863. After he returned home to Plympton, Edmond remained very active in the GAR.

Edmond was the son of Erastus & Maria B. Leach. He was married in 1876 to Sarah Elizabeth Weston (1848-1923). He died in 1917 and was buried in Vine Hills Cemetery.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Fort Berry, Va.

August 22nd 1864

Dear Friend Ella,

I received your kind letter on the 20th and was glad to hear from you. There’s not much to write about anyway. It has been raining all day. I think that it will continue to [rain] for some days.

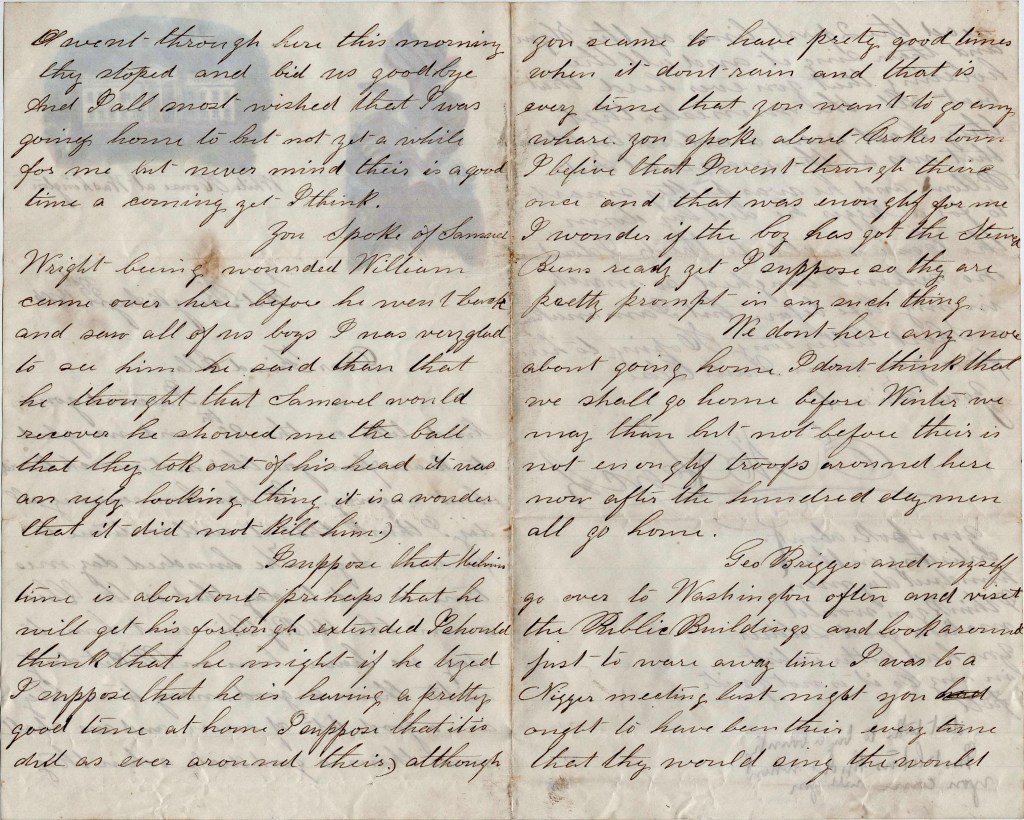

The Hundred Day Men’s time is out today—that is, the Ohio men. The 166th Reg. Ohio went home today. We have been on picket duty with them a good many times. They are a good set of men and we shall miss them a good deal. When they went through here this morning, they stopped and bid us goodbye and I almost wished that I was going home too but not yet a while for me. But never mind. There is a good time a coming yet.

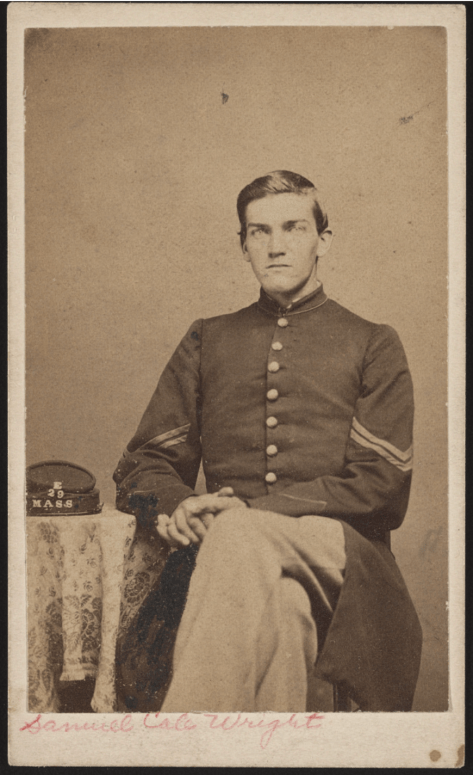

You spoke of Samuel [Cole] Wright 1 being wounded. [His older brother] William came over here before he went back [to Plymouth] and saw all of us boys. I was very glad to see him. He said then that he thought that Samuel would recover. He showed me the ball that they took out of his head. It was an ugly looking thing. It is a wonder that it did not kill him.

I suppose that Melvin’s time is about out. Perhaps that he will get his furlough extended. I should think that he might if he tried. I suppose that he is having a pretty good time at home. I suppose that it is dull as ever around there although you seem to have pretty good times when it don’t rain and that is every time that you want to go anywhere. You spoke about Crokestown. I believe that I went through there once and that was enough for me. I wonder if the boy has got the stewed buns ready yet? I suppose so. They are pretty prompt in any such thing.

We don’t hear any more about going home. I don’t think that we shall go home before winter. We may then but not before. There is not enough troops around here now after the Hundred Days Men all go home.

George Briggs and myself go over to Washington often and visit the public buildings and look around just to wear away time. I was to a Nigger meeting last night. You ought to have been there. Every time that they would sing, they would read the two first lines of the hymn and then sing it. And all the hollering that you ever heard! That beat all. The minister that they had was a colored gentleman 2 that was at the massacre at Ft. Pillow [April 1864] and he was pretty smart too for a Nigger. He did lay down the case well to them. I don’t know when I laughed so much in my life before. But I am making a short letter long.

Hoping to hear from you soon, I will close. Your friend, — E. M. Leach

You spoke about enlisting in the Hundred Days Men. I think you would make a good soldier. You had better enlist in my company. It is not quite full. Don’t take too big a bounty. Just let us know when you come, will you?

1 According to a great article by my friend, Ron Coddington, entitled, “Samuel Cole Wright: The Talisman,” Samuel Wright of Plympton, Plymouth county, Massachusetts, had a combat record that left one with the impression that he was indestructible. “He refused to leave his comrades after a shell fragment struck him in the head during the Battle of White Oak Swamp, part of the Peninsula Campaign, in June 1862. A few months later at Antietam, he led a force of 75 men to pull down a fence at the Bloody Lane under heavy fire and suffered gunshot wounds through both legs at the end of the successful mission. A six-mule team trampled over him during the autumn of 1863, and the wagon to which the animals were tethered narrowly missed killing him.5 A musket ball ripped into his left arm at the Battle of Cold Harbor on June 3, 1864. The following month at the Battle of the Crater, he suffered his fifth and final wound of the war when a bullet destroyed his right eye and lodged in the back of his skull. Medical personnel dug the 1.25 ounce lead slug out and upon examination determined it to be from a Belgian-made gun.” Samuel had the bullet encased in gold and carried with him as a remembrance of his service. In February 1865 he received a disability discharge and returned to Massachusetts. Samuel’s letters can be found here: Letters Home.

2 There were churches for Black congregations in the District of Columbia prior to 1864 but White pastors had always been appointed to lead them. It wasn’t until 1864 that the first Black pastor was appointed at the Mt. Zion Church in Washington D. C.