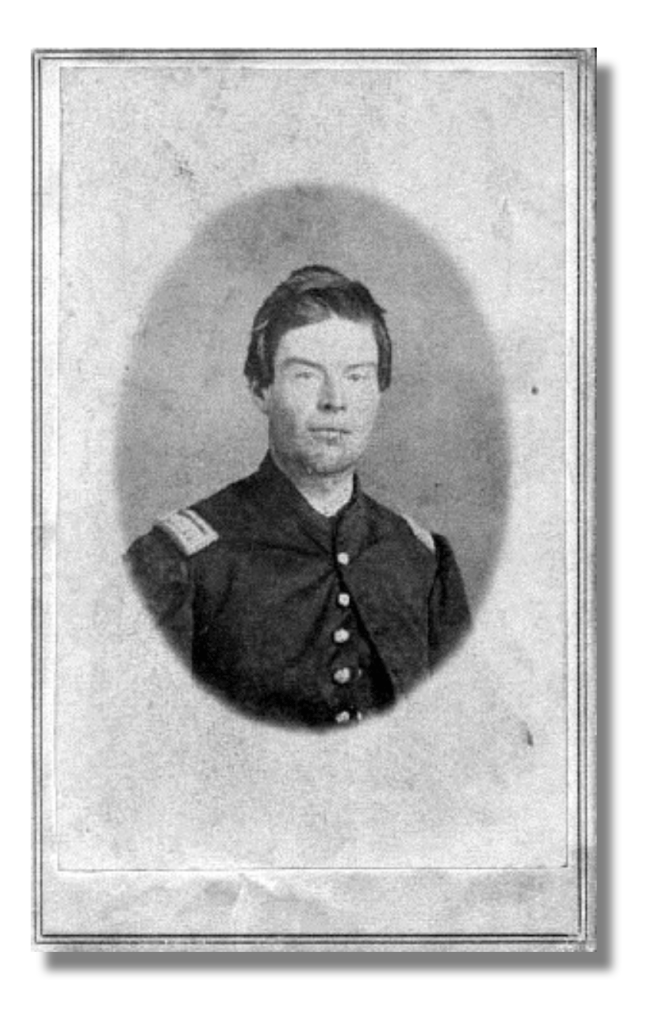

John Russell was 33 years old when he volunteered to serve in Co. G, 21st Illinois Infantry. He was the son of Alexander Russell (1794-1863) and Jane Jack (1797-1873) and was still living and working on his father’s farm in Clay county, Illinois, at the time of the 1860 US Census. Living in the household as well was his younger sister C. Sophia Russell (1840-1934), to whom he addressed his letter.

The muster rolls of the 21st Illinois inform us that John mustered into the company on 28 June 1861 and he was discharged for disability on 24 March 1864. The regiment’s first colonel was Ulysses S. Grant. It was ordered to move to Ironton, Missouri, on July 3, but instead operated on the line of the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad until August. Grant was promoted to brigadier general and became commander of the District of Southeast Missouri on 7 August, being replaced by regimental lieutenant colonel John W. S. Alexander. The regiment reached Ironton on 9 August 1861 and saw its first action at the Engagement at Fredericktown in late October. The first major engagement was at Stones River in December 1862 and January 1863. It was shortly after that battle that John wrote a letter to his sister Sophia in which he provided great detail of the regiment’s action. See “Getting Bitten by the Bait: The 21st Illinois at Stones River” by Dan Masters (Civil War Chronicles).

Transcription

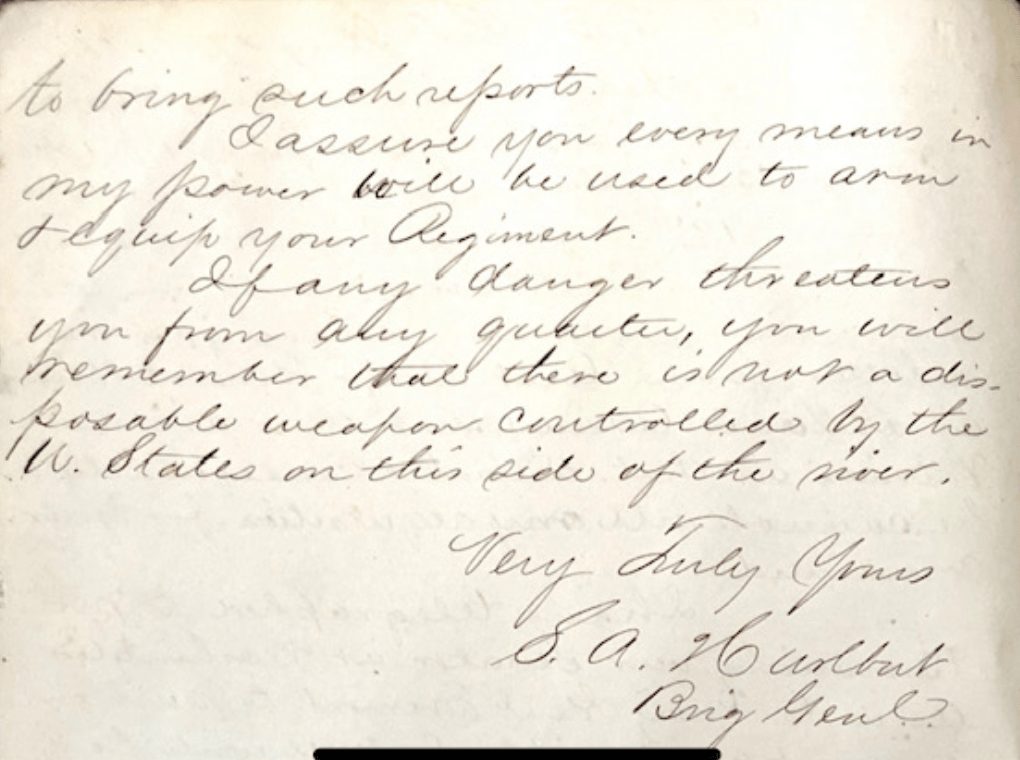

Ironton, Missouri

November [1861]

Dear Sister,

I take my pen to write you a few lines to inform you of my health which is very good, and there is little else to write. I received a letter from Doc some time since and one from Ann on Saturday and was glad to hear from you all. I have had no time to write for the last two or three weeks, having been in camp but little and on duty all the time. As week ago I expected to be at home now and had my furlough made out but an order was issued forbidding the granting of any more furloughs at present and mine was not signed yet. I could not come but I hope to soon.

We are stationed here for the winter and are at work here now a putting up winter quarters. I have had charge of 20 men for the last 4 days a chopping and hauling logs and only get to write now by getting F. M. Finch to take my place this afternoon. We will get them up in 4 or 5 days more. We have had a fine fall, but it is a little cold now. We had a fine little snow on Friday last, and we are in a hurry to get to our new quarters.

I think the government will soon put forth all its energies which it has been so long gathering to put down this rebellion. We know here that when furloughs are denied, a move is on foot and this denial is now universal and we know there is a general movement of importance contemplated and I hope its success will more than compensate me for the disappointment of not getting to go home.

“I am not waging a war for emancipation but I would seize the slaves of every rebel and set them to work at wages or to fight as most convenient and at the close of the war, give them their freedom…”

John Russell, Co. G, 21st Illinois Infantry, November 1861

There was a feeling of general indignation at the removal of Frémont and still more at the order of General Halleck that all fugitive slaves in our camps or that may come to them hereafter must be driven off. But in all there is a determination to sustain the government hoping that it would be compelled to come around right in time. All that is wanting to a speedy success is a man to hold up the thing square and use the means of success that we possess. I am not waging a war for emancipation but I would seize the slaves of every rebel and set them to work at wages or to fight as most convenient and at the close of the war, give them their freedom, placing them wherever Providence opened up a place. Thus we would get rid of slavery and by having them on hand, it is likely that the best disposition would be made of them that could.

I think the war will be over by the first of May unless there are some serious blunders on our part. I think our troops will occupy Memphis and Nashville in four weeks from this time.

But I must close. I hope this may find you all well. I send enclosed to Pap 25 dollars. I still save enough to bring me home if opportunity occurs. We have a good time here—plenty to eat and plenty to wear and not much to do. Write often and I will as often as I can. Yours, &c. — John Russell

To Miss C. S. Russell