The following letters were written by Seymour Dexter (1841-1904), the son of Daniel Dexter (1806-1891) and Angeline Briggs (1816-1891) of Independence, Allegany county, New York. Seymour received his preparatory education at Alfred Academy and graduated from Alfred University in 1864 (A.M., Doctor of Philosophy). Studied law,1864-1866. He was admitted to the bar at Elmira in 1866 and became the City Attorney in 1872. In that same year he was elected to the New York Assembly.

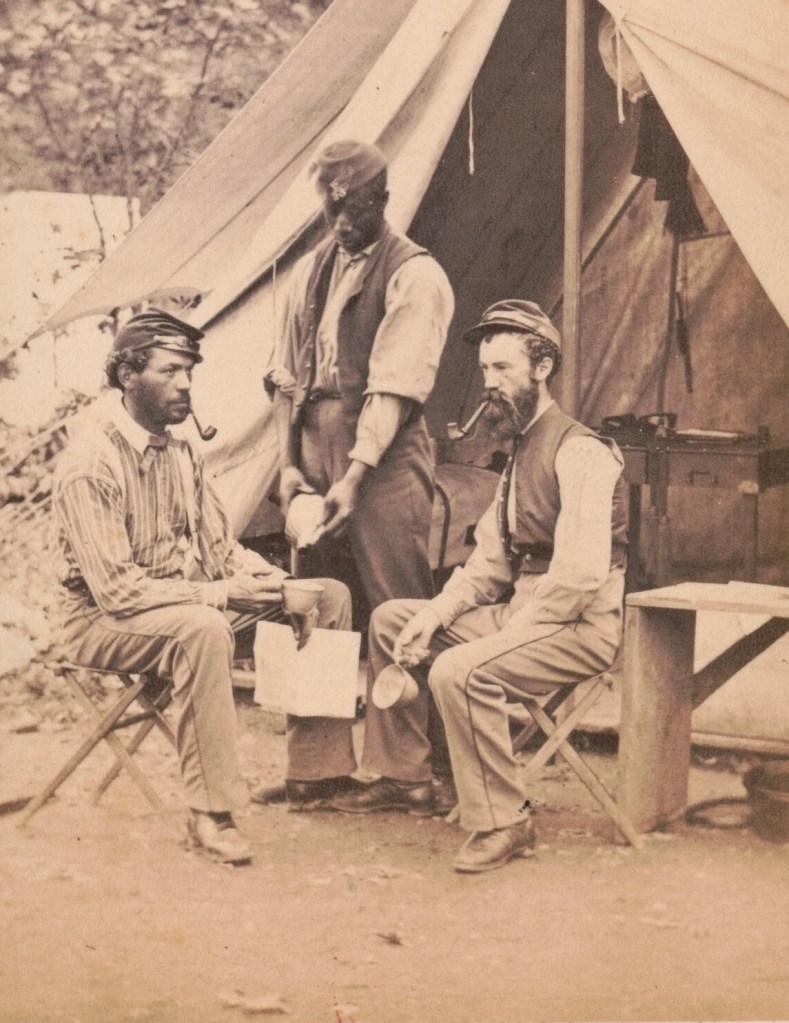

Seymour enlisted in May 1861 at Elmira to serve two years in Co. K, 23rd New York Infantry. He entered the war as a private, was promoted to corporal in Mach 1863 and mustered out of the regiment on 22 May 1863. There was a book published in 1996 by Carl A. Morrell which contained the Civil War writings of Seymour Dexter [See: Seymour Dexter, Union Army: Journal and Letters of Civil War] but I don’t believe that this letter was included. The introduction to that book states, “‘Freedom, the true government, has called upon her loyal sons, and as our response to this call and also to the demands of truth and humanity, seven of us determined on the 26th day of April, 1861 that we would immediately volunteer our services in the defense of the stars and stripes.’ So wrote Seymour Dexter in the opening pages of his Civil War journal. A student at the time of Fort Sumter, Dexter joined Co. K in Elmira, New York. Private Dexter, who would enjoy a distinguished career as a lawyer following the unpleasantness, gives us an unusually keen view of the war, capturing the emotions of the men in the field and the camaraderie of Company K.”

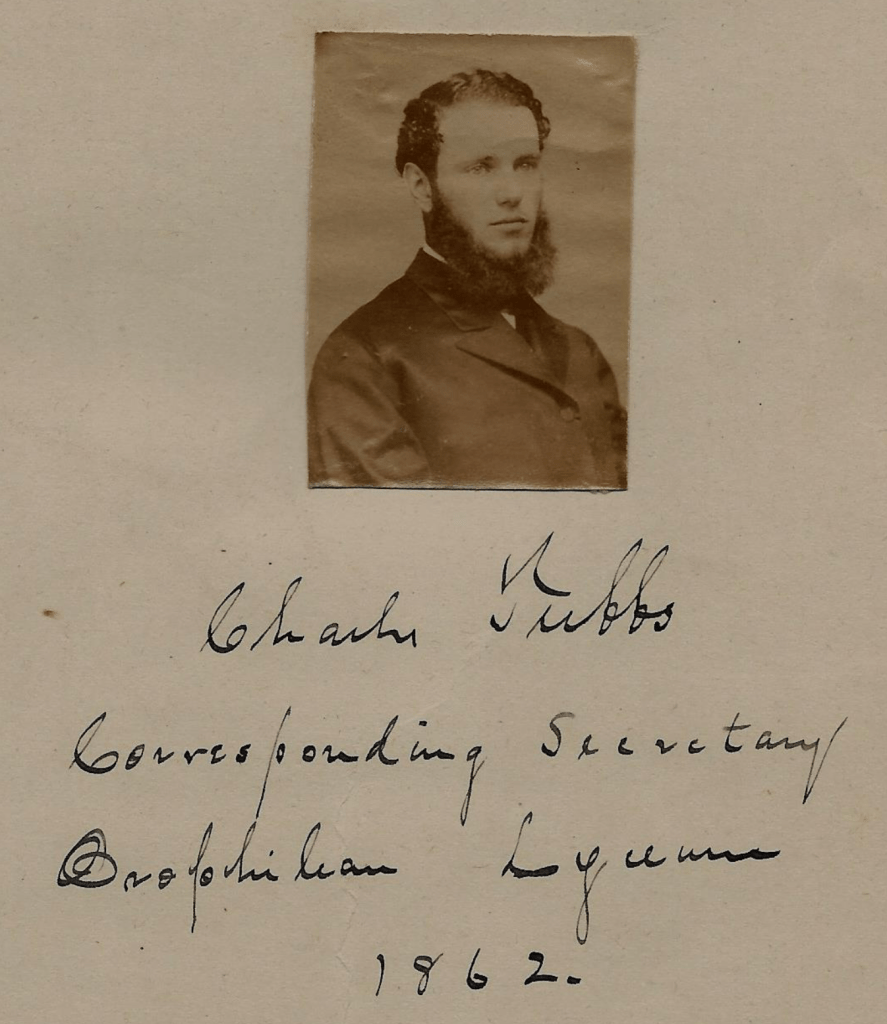

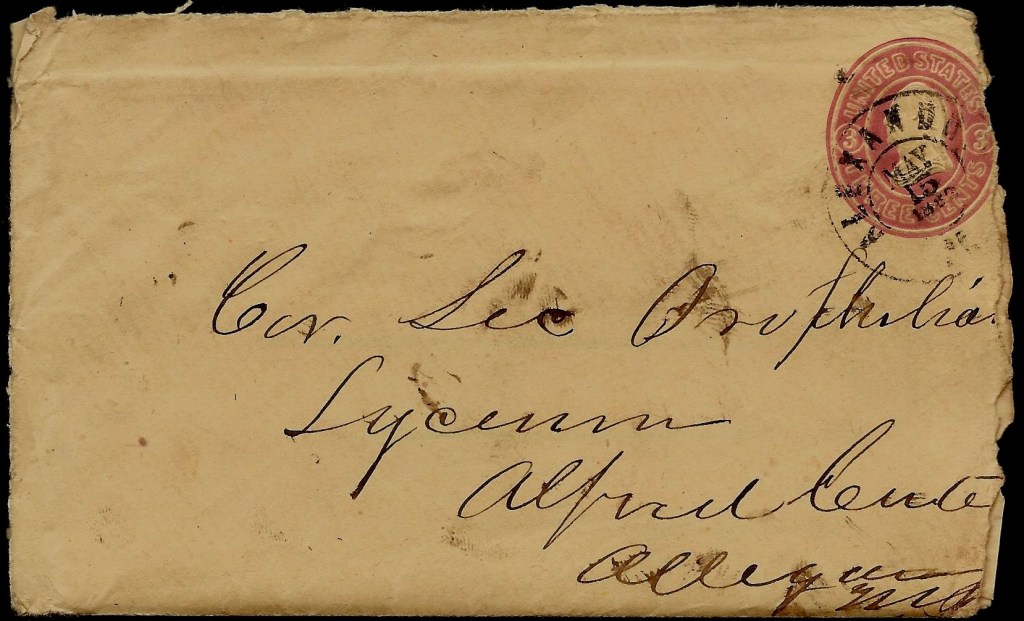

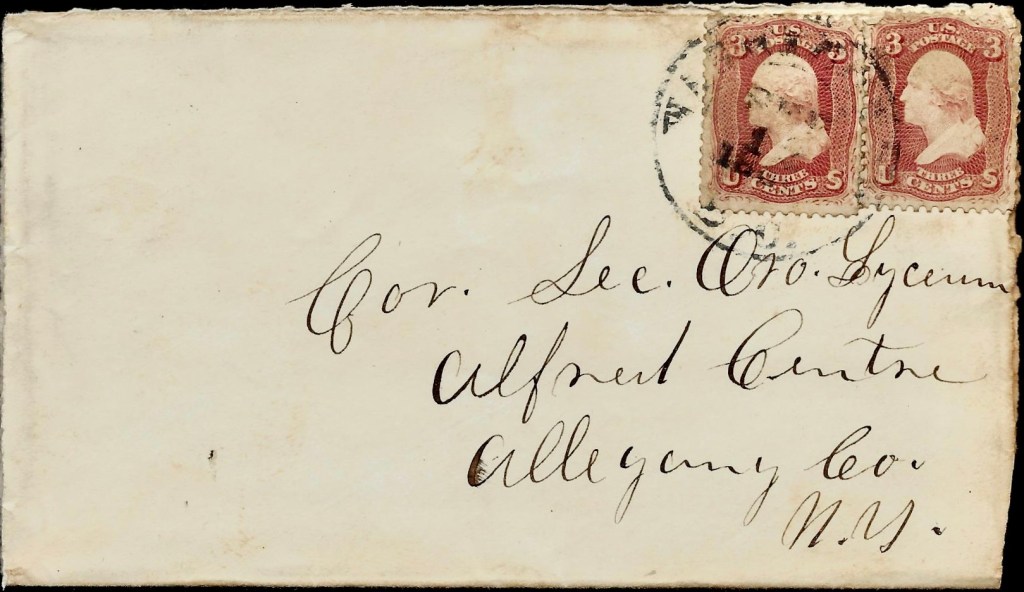

Dexter wrote the letters to Charles Tubbs, the corresponding secretary of the Orophilian Lyceum of Alfred University in Alfred Centre, New York. Founded in 1836, Alfred University was an early-day coeducational college. Tubbs later attended Union College, graduated with honors in 1864, and then attended the law school in Ann Arbor, Michigan. In researching Tubbs, I was surprised to discover a 1996 publication entitled, “Mr. Tubbs’ Civil War” by Nat Brandt. In his introduction. Brandt wrote that, “Charlie Tubbs experienced the Civil War vicariously. He never volunteered nor was drafted in the Union military forces. But many of his friends went to war, and it was through them that the day-to-day experience of the war came alive for him in the most personal way. Throughout the war, Tubbs received more than 175 letters from his friends, ordinary young men, all products of rural New York and Pennsylvania.” Curiously, of the 17 letter writers mentioned in Brandt’s publication, Seymour Dexter is not listed and his letters do not appear in the book. It may be that these letters, which were once part of a larger collection of Tubb’s collection, were separated from the rest at an early date. It may also be possible that Brandt chose not to include these letters in his book for some reason.

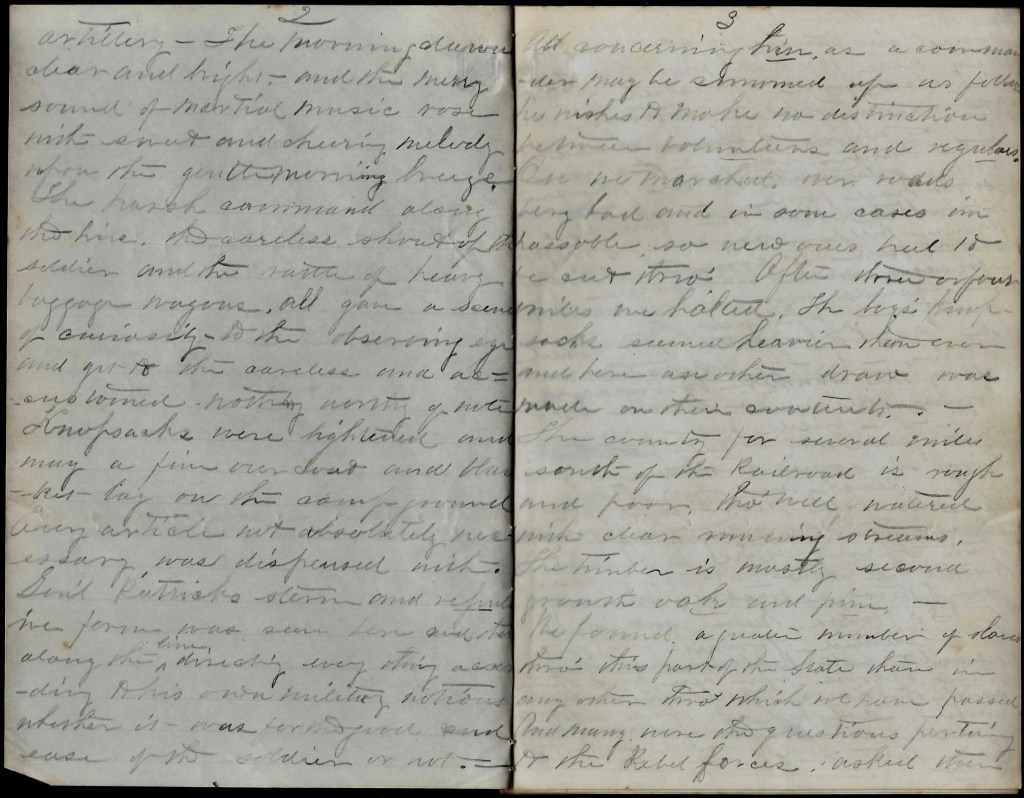

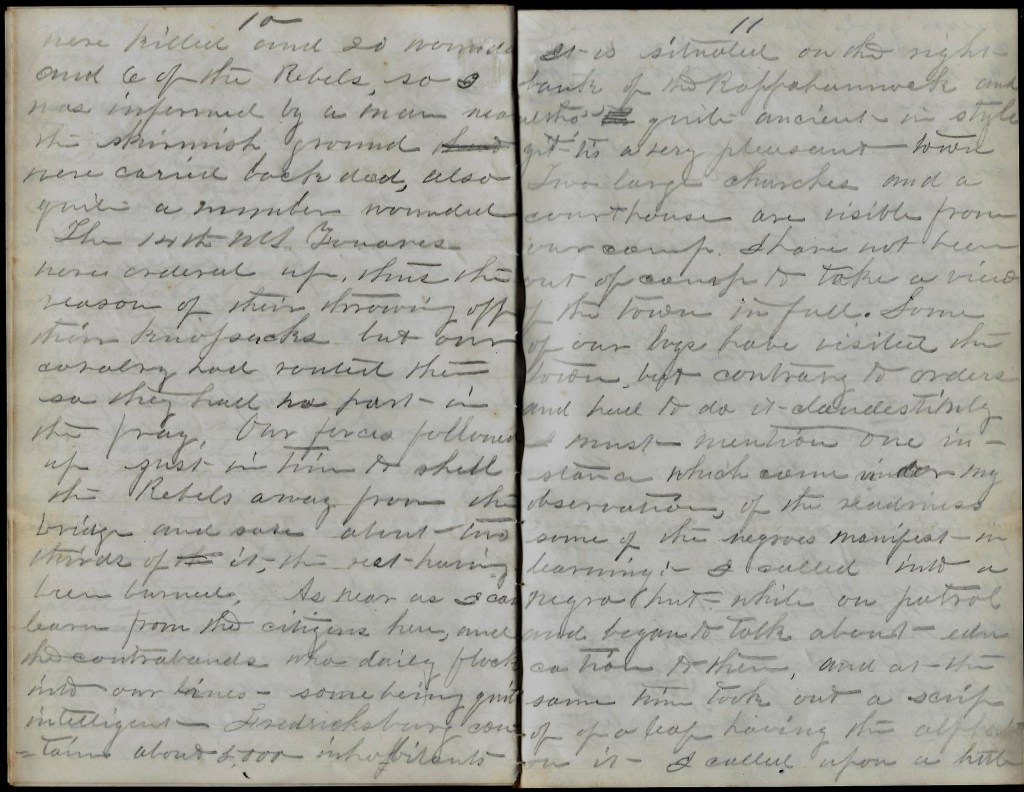

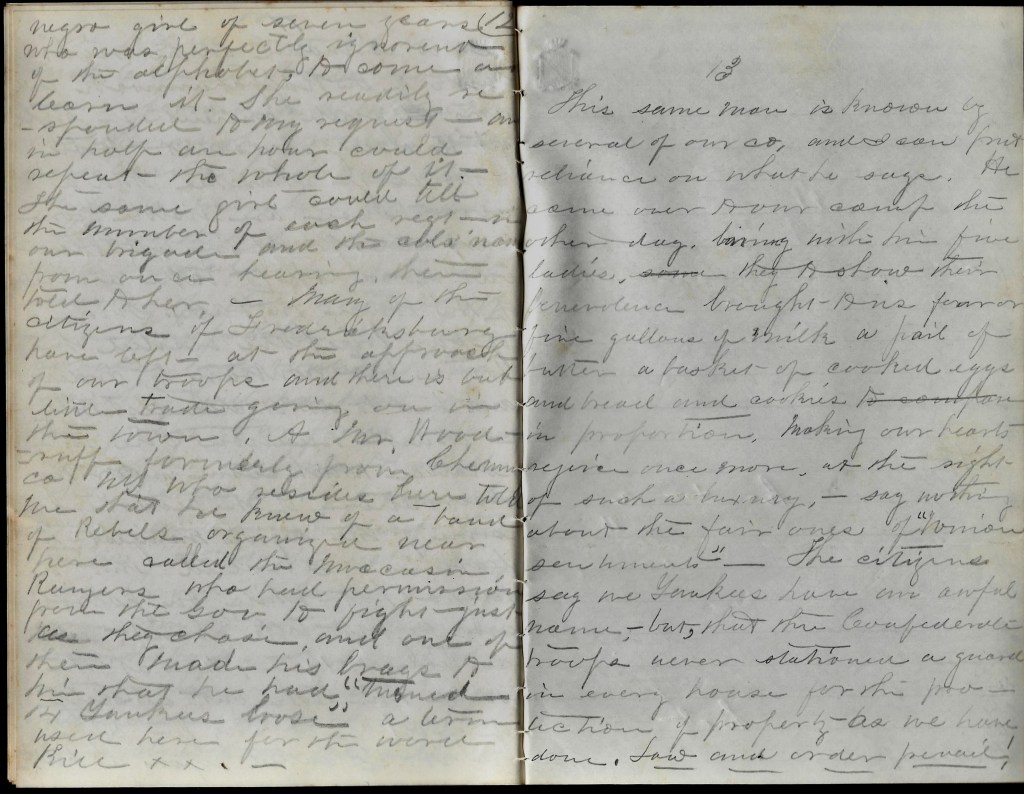

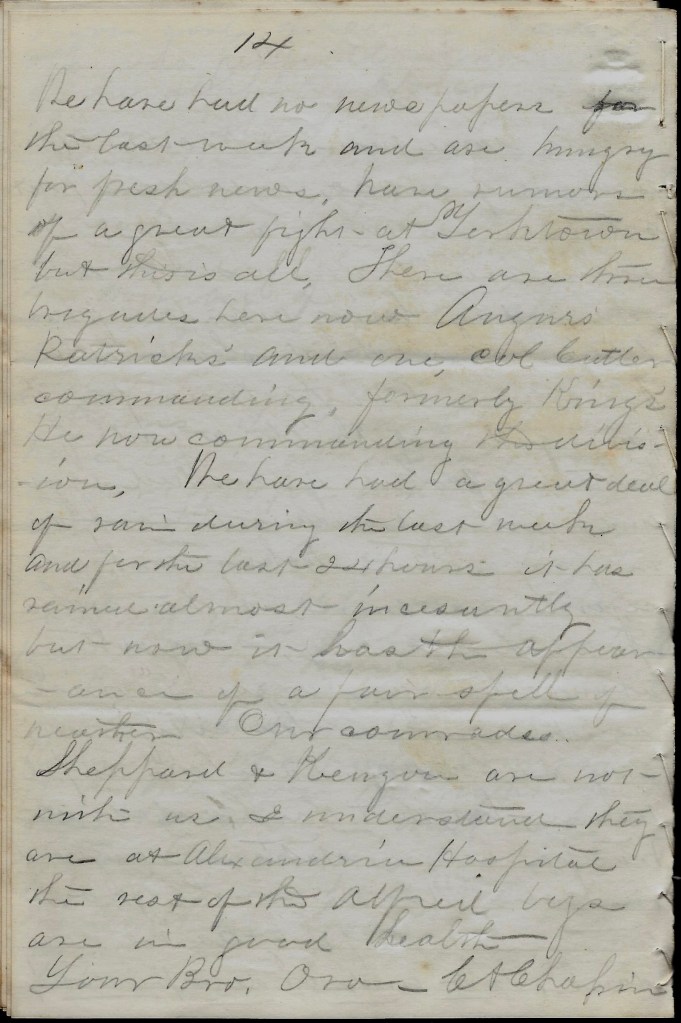

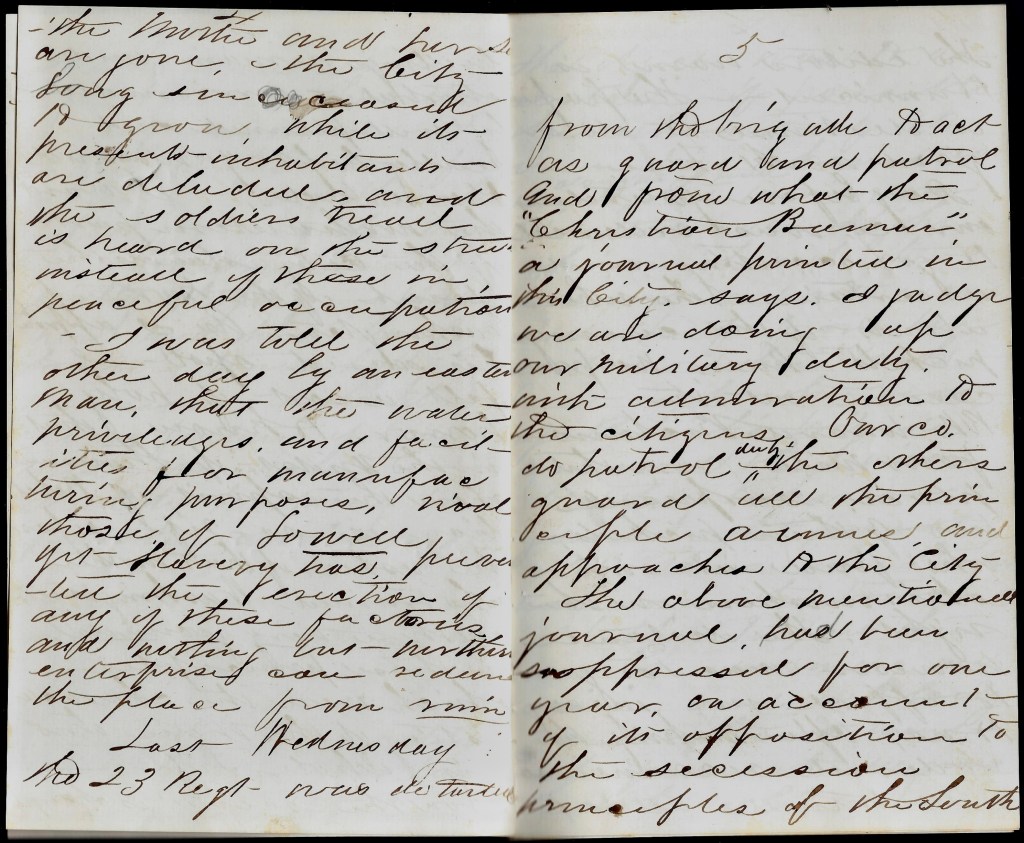

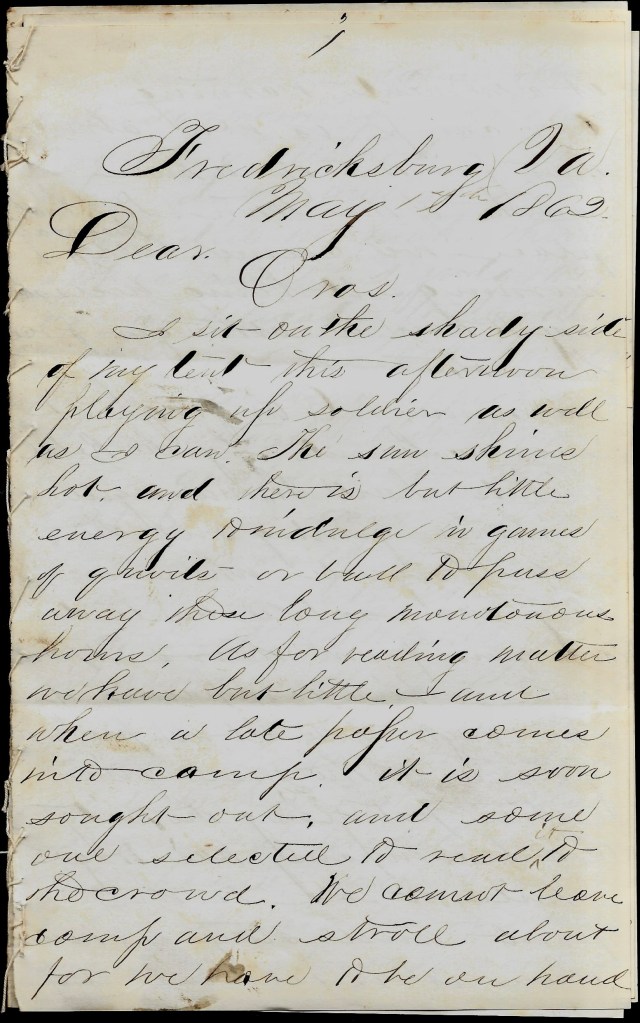

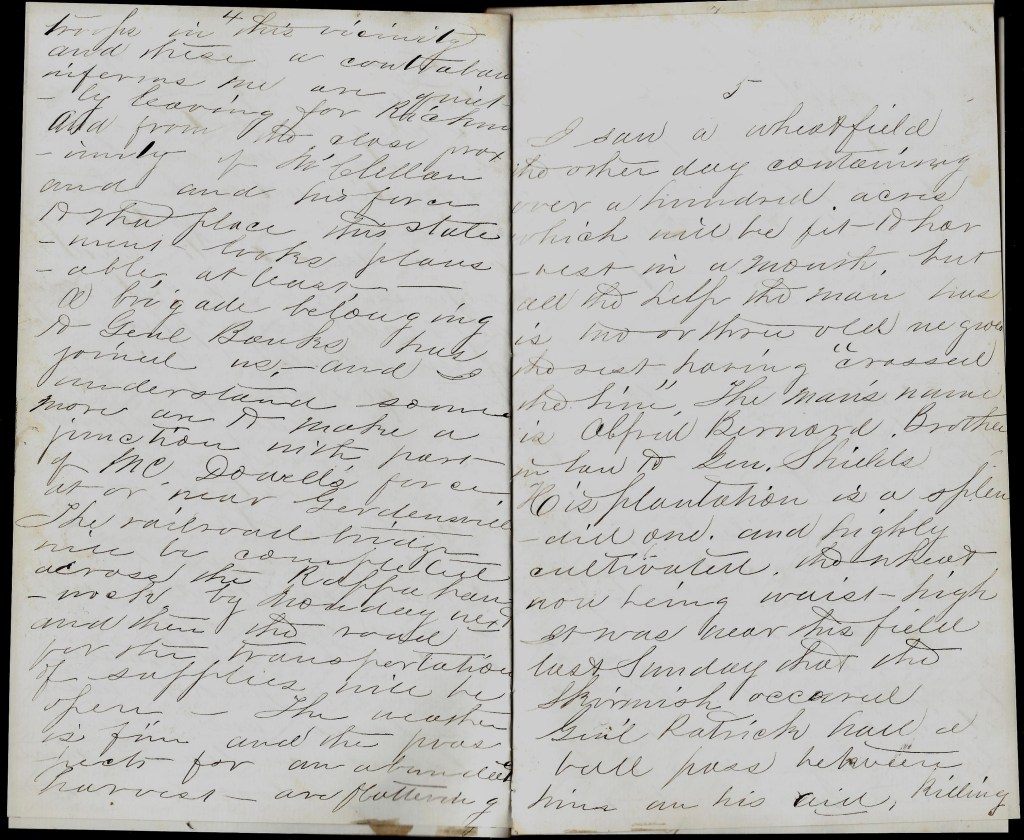

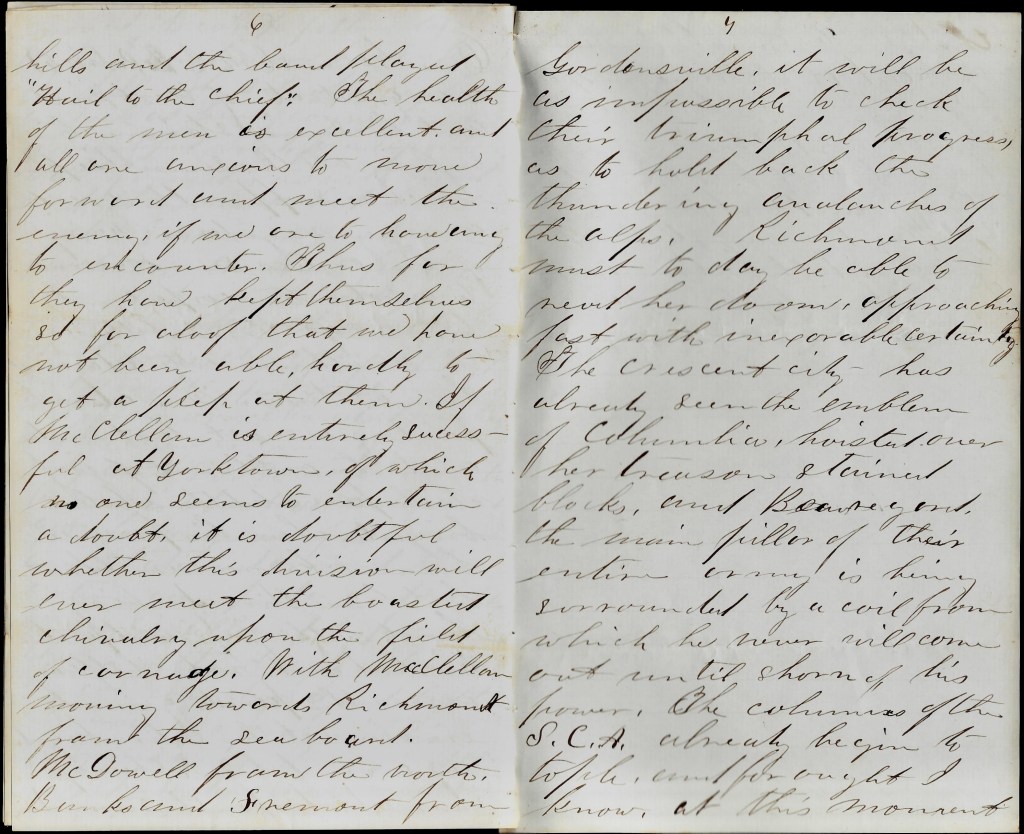

Letter 1

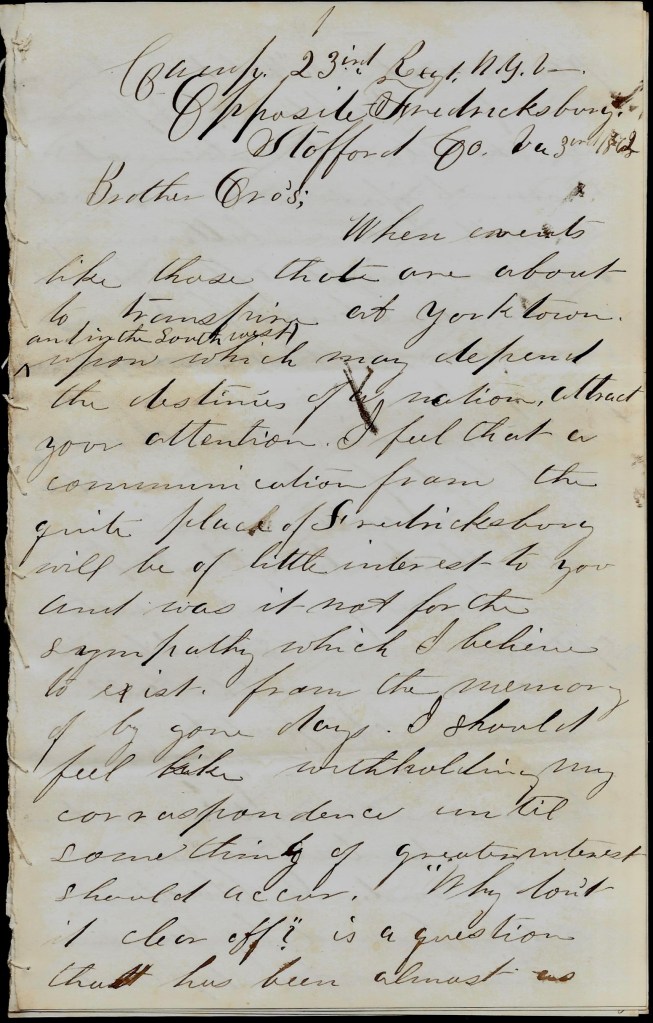

Camp 23rd Regt New York Vol.

Opposite Fredericksburg, Stafford County, Va.

May 3, 1862

Brother Oro’s:

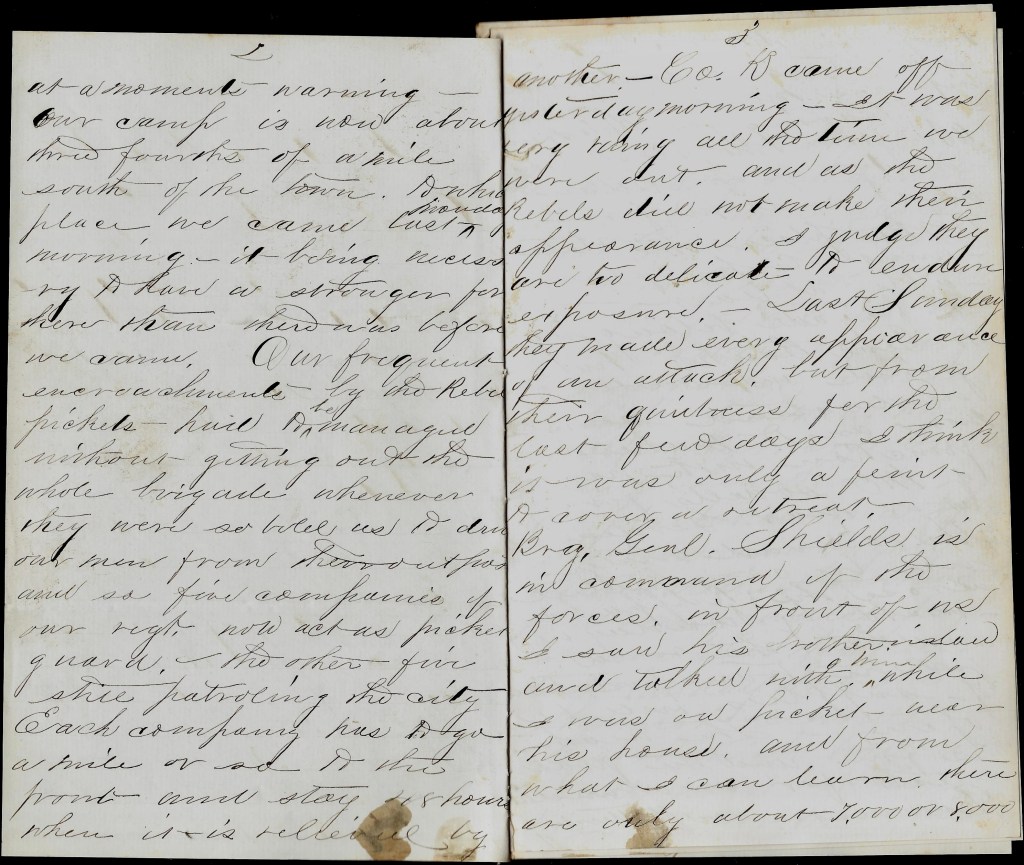

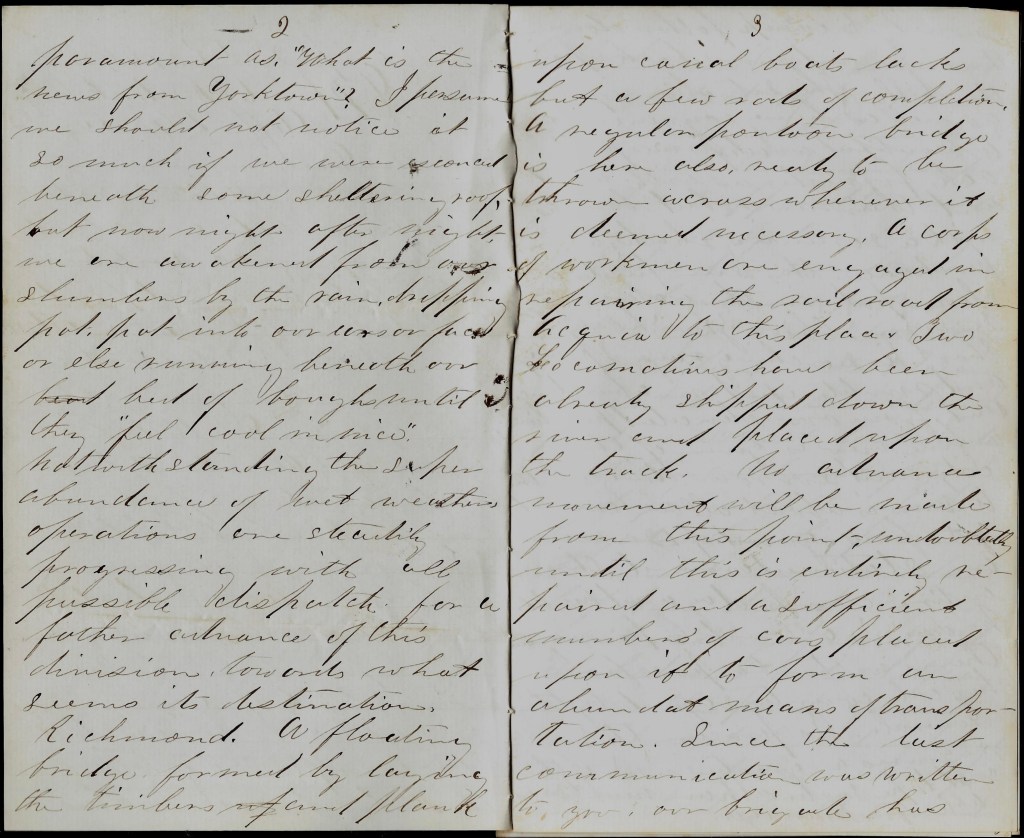

When events like those that are about to transpire at Yorktown and in the southwest upon which may depend the destinies of the nation attract your attention, I feel that the quiet place of Fredericksburg will be of little interest to you and was it not for the sympathy which I believe to exist from the memory of bygone days, I should feel like withholding my correspondence until something of greater interest should occur.

“Why don’t it clear off?” is a question that has been almost as paramount as, “What is the news from Yorktown?” I presume we should not notice it so much if we were ensconced beneath some sheltering roof but now night after night, we are awakened by the rain, dripping pot, pot into our face or else running beneath our bed of boughs until they “feel cool in vice.” Notwithstanding the super abundance of wet weather operations one steadily progressing with all possible dispatch for a further advance of this division towards what seems its destination—Richmond.

A floating bridge formed by laying the timbers and plank upon canal boats lacks but a few rods of completion. A regular pontoon bridge is here also, ready to be thrown across whenever it is deemed necessary. A corps of workmen are engaged in repairing the railroad from Aquia to this place. Two locomotives have been already shipped down the river and placed upon the track. No advance movement will be made from this point undoubtedly until this is entirely repaired and a sufficient number of cars placed upon it to form an abundant means of transportation.

Since the last communication was written to you, our brigade has moved its camp farther down the river and more back upon the hill. The situation is pleasant as well as being convenient. A beautiful wood, principally oak, furnishes us with wood, and their new, robust boughs with a screening shade when, perchance, the sun finds a clear spot in the watery reservoir through which to shoot his searching rays. Springs and rivulets exist in abundance and from our elevated position a fine view is given of the city and surrounding country. A view is about all we can get for a guard of 120 men are stationed around the entire camp, day and night. No one is allowed to pass from his colonel, countersigned by the general. To procure this requires a greater use of the “red tape system” than most are able to manage.

Our General, (M. R. Patrick) is a graduate of West Point and he seems striving to enforce all the severe discipline which is supposed to exist among regulars. Many of his orders seem onerous to a volunteer corps and to speak in soft terms, bitter are the anathemas uttered against him at times.

Gen. Wadsworth paid us a visit last Sunday and the outburst of joy which pervaded the whole brigade when his presence became known could not but have stirred his heart with joy and pride. He had not rode halfway across the parade ground ere almost the entire brigade was around him. Cheer upon cheer echoed upon the surrounding hills and the band played “Hail to the Chief.”

The health of the men is excellent and all are anxious to move forward and meet the enemy if we are to have any to encounter. Thus far they have kept themselves so far aloof that we have not been able hardly to get a peep at them. If McClellan is entirely successful at Yorktown, of which no one seems to entertain a doubt, it is doubtful whether this division will ever meet the boasted chivalry upon the field of carnage. With McClellan moving towards Richmond from the seacoast, McDowell from the north, Banks and Fremont from Gordonsville, it will be as impossible to check their triumphal progress as to hold back the thundering avalanches of the alps. Richmond must today be able to read her doom approaching fast with inexorable certainty.

The Crescent City has already seen the emblem of Columbia hoisted over her treason stained blocks, and Beauregard—the main pillar of their entire army—is surrounded by a coil from which he never will come out until shorn of his power. The columns of the S. C. A. already begin to topple and for ought I know, at this moment the thunder of battle may be heard at the renowned place of Yorktown and in the Southwest, the concussion of which will fell them to the ground, and over their eclipsed majesty shall be raised the standard of the free forever and age. — S. Dexter

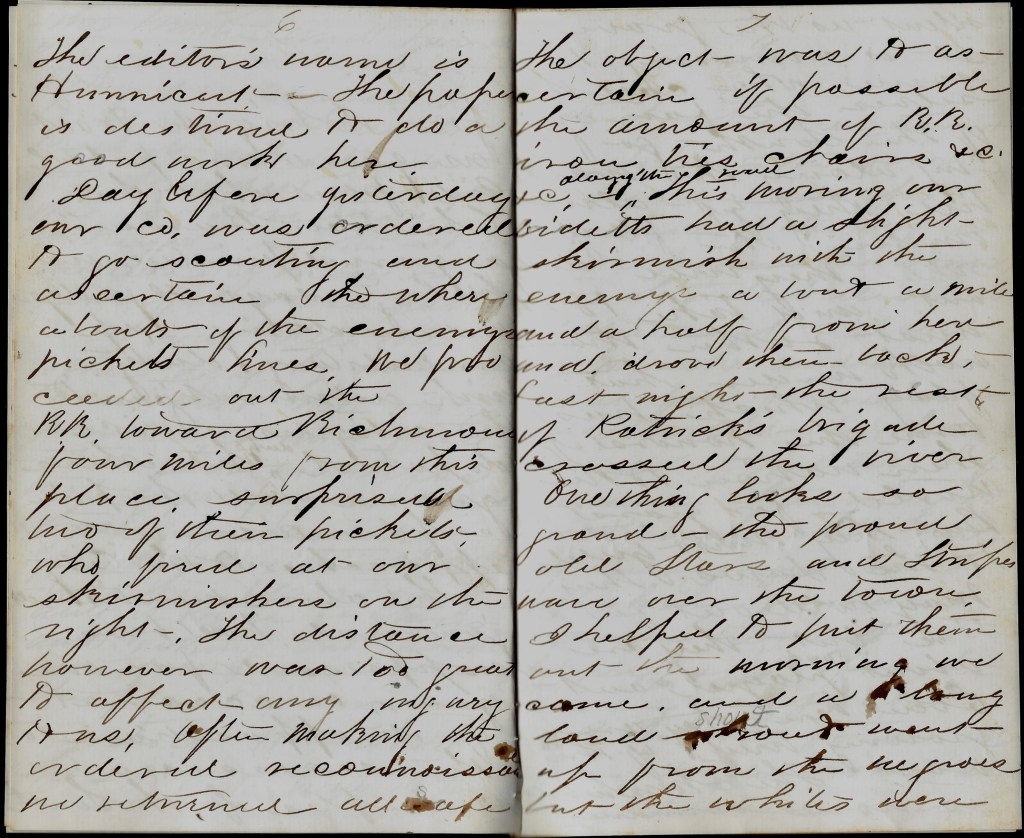

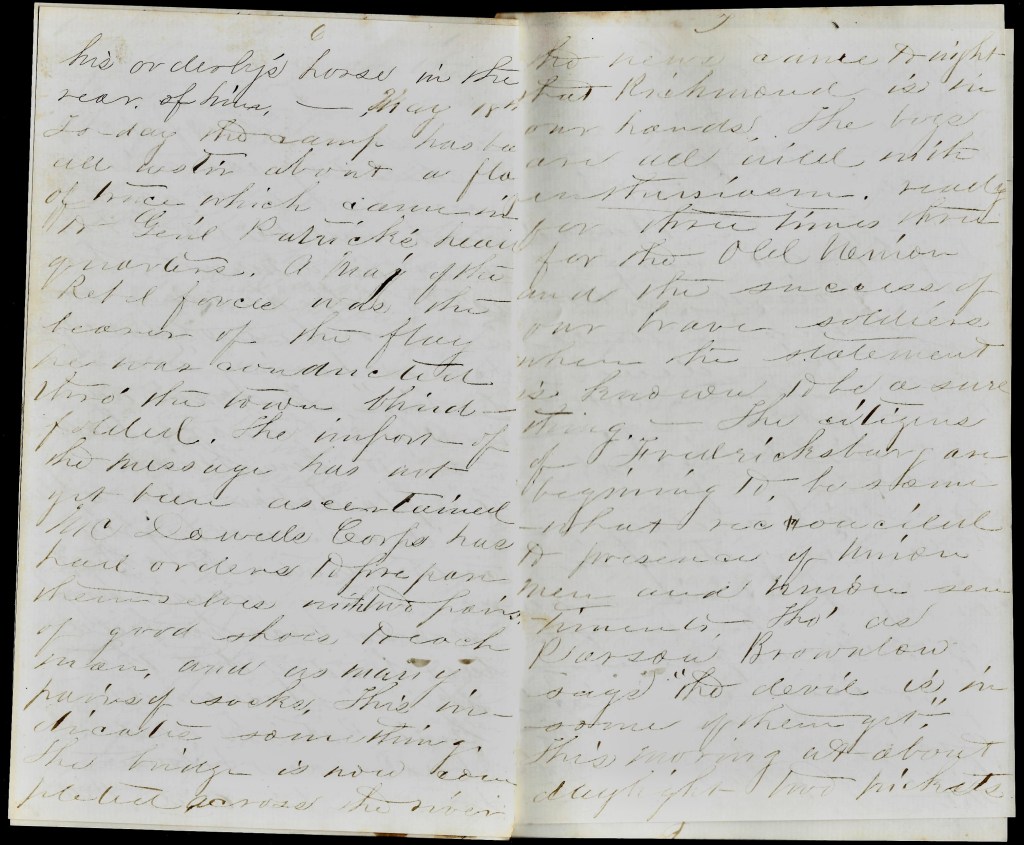

Letter 2

Leesborough, Maryland

September 9th, 1862

Brother Oro’s:

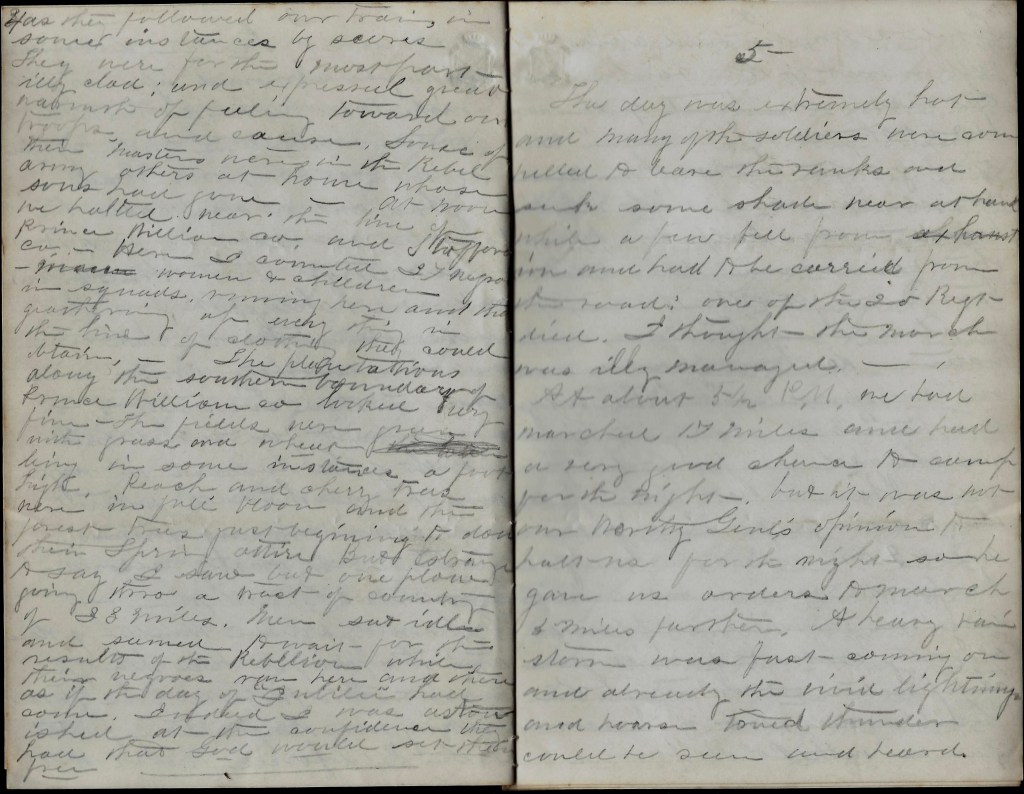

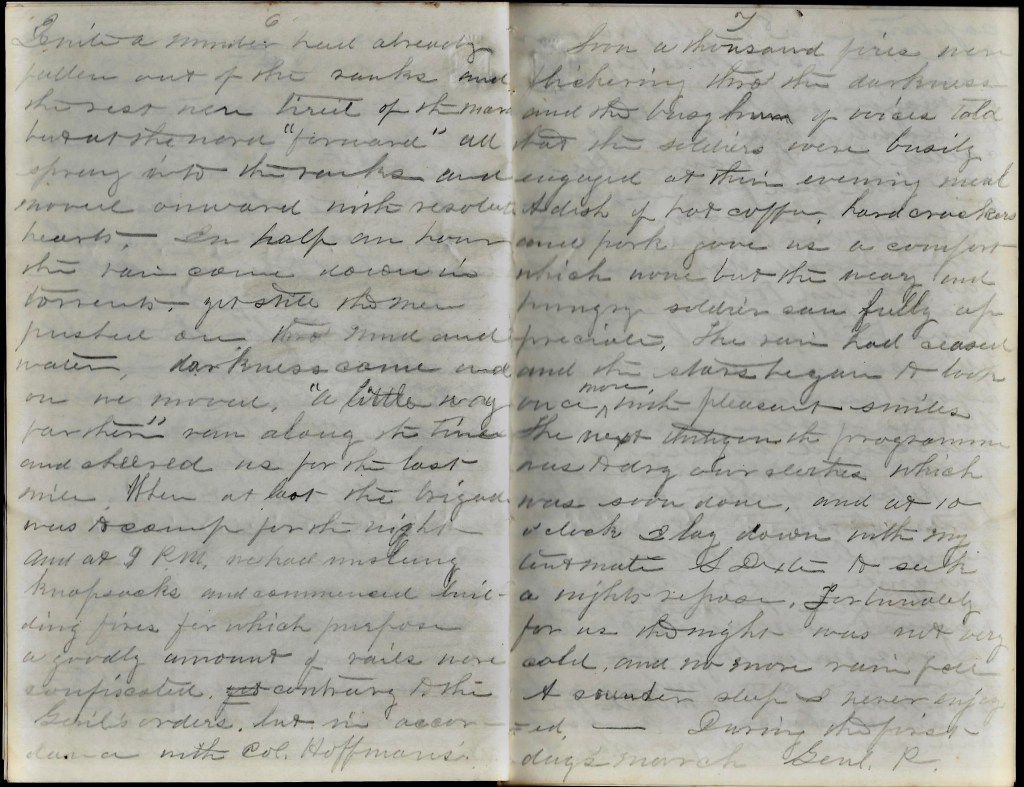

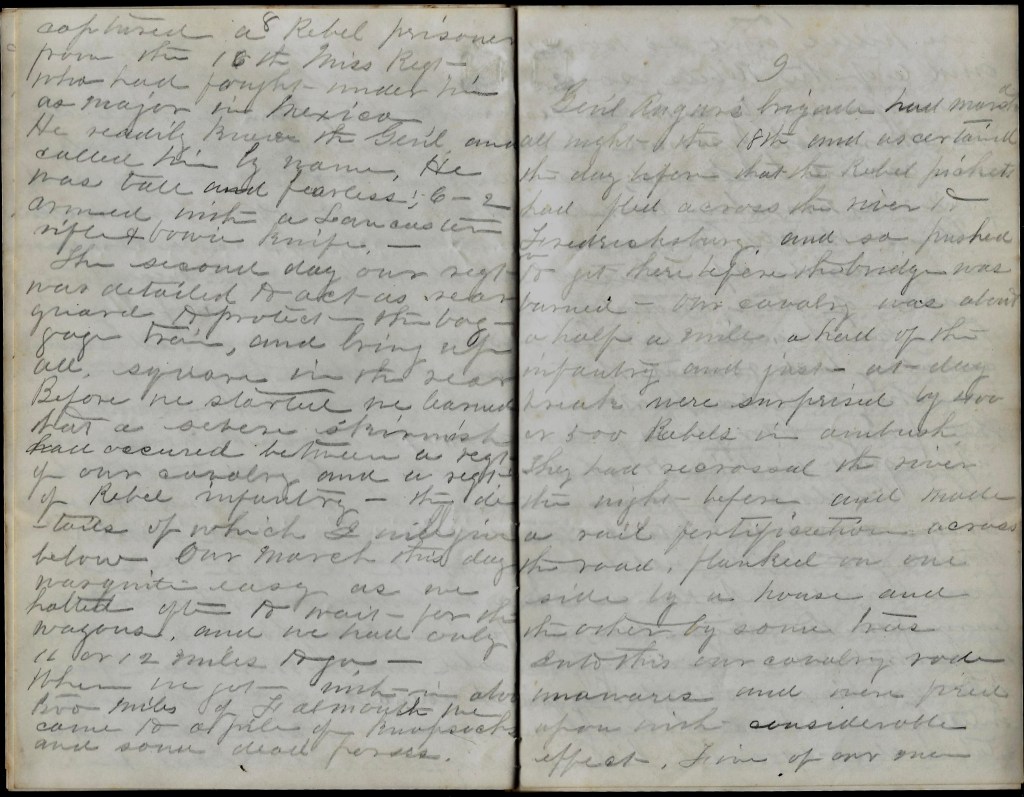

The labors and fatigues of the last three weeks have made the pen a useless article to the soldier but now some miles nearer the north star than ever before since we landed in Washington one year ago last July. A short interval has been allowed us to rest amid our dancings to “Stonewall Jackson’s” music. On the night of the 18th ult. the “Army of Virginia” with its boastful leader [Maj. Gen. John Pope] began its retreat from the Rapidan and which did not cease until a portion of it was lodged behind the lines of defense about Washington and the other portion of McClellan’s army and also that of Burnside’s. From the 22nd ult. until the 3rd inst., not a day passed but the thunder of cannon was borne to our ears and many of the conflicts were most desperate and bloody. On the 22nd ult., our Division was engaged in an artillery duel across the Rappahannock near the Station, our regiment supporting a section of one of our batteries. From there we marched to Sulphur Springs via Warrrenton where upon the 25th ult. we were again in an artillery fight with skirmishing—our regiment acting as a guard on the left flank with companies K & G thrown out as skirmishers. Here for the first time as a company we fired our guns at real rebels.

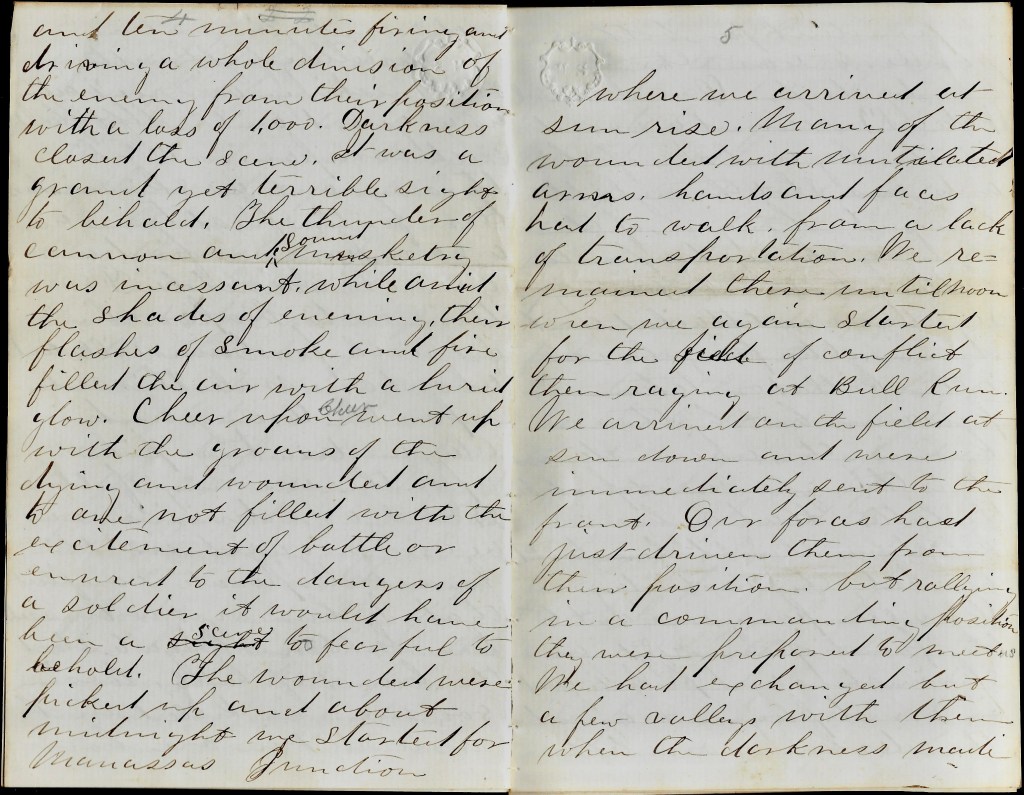

From there we took up our line of march for Gainesville and about one mile this side upon the Orange and Alexandria turnpike, upon the evening of the 27th ult., our Division was again engaged in the most desperate conflict [see Brawl at Brawner’s Farm] that I have yet witnessed. Gen. Gibbon’s Brigade stood the brunt of the battle, losing 800 men in killed and wounded in one hour and ten minutes firing and driving a whole division of the enemy from their position with a loss of 1,000. Darkness closed the scene. It was a grand yet terrible sight to behold. The thunder of the cannon and sound of musketry was incessant, while amid the shades of evening their flashes of smoke and fire filled the air with a lurid glow. Cheer upon cheer went up with the groans of the dying and wounded and to one not filled with the excitement of battle or inured to the dangers of a soldier, it would have been a scene too fearful to behold.

The wounded were picked up and about midnight we started for Manassas Junction where we arrived at sunrise. Many of the wounded with mutilated arms, hands and faces had to walk from a lack of transportation. We remained there until noon when we again started for the field of conflict then raging at Bull Run. We arrived on the field at sundown and were immediately sent to the front. Our forces had just driven them from their position but rallying in a commanding position, they were prepared to meet us. We had exchanged but a few volleys with them when the darkness made it prudent for both parties to cease the bloody strife. Our General (Patrick) received a wound in the leg and one of his aides was shot through the lungs. A brigade of the enemy charged upon the battery to which Tommy Sanders was attached and during the fray, he was either killed or taken prisoner. But by those knowing the circumstances, it is thought most probable the latter. Had he been killed we should have found his body the next day.

Our company was out to the front of our regiment as skirmishers and pickets and in our deployment amid the darkness, our left ran in between two bodies of the enemy. Two privates and one sergeant were taken prisoners while two others made their escape with an orderly sergeant of the enemy a prisoner. That day had proved a victory to our arms and all felt confident on the morrow of sending the rebel horde back to the mountains with as great speed as they had come up.

Morning showed the enemy to have fallen back and taken up a new position. Very heavy reinforcements arrived for them during the night and morning. The forenoon was spent in arranging our forces and preparing for the attack. Whoever planned was out generaled by the enemy and the sequence proved most fatal to our cause. McDowell’s Corps began the attack between one and two o’clock with cannon and skirmishing. Our Division had the right of the centre. We advanced in two lines of battle, our regiment being in the second. We had to push through a dense piece of woods beyond which lay the enemy. As soon as our front lines became visible, they opened with battery after battery and infantry, filling the woods with a perfect shower of shell, grape, canister, and musket balls. Still our lines in the centre and right pressed forward and for the moment broke the enemy’s centre but we soon found the enemy were turning the left flank and thus getting an enfilading fire upon us and cutting us off from the position held before the attack.

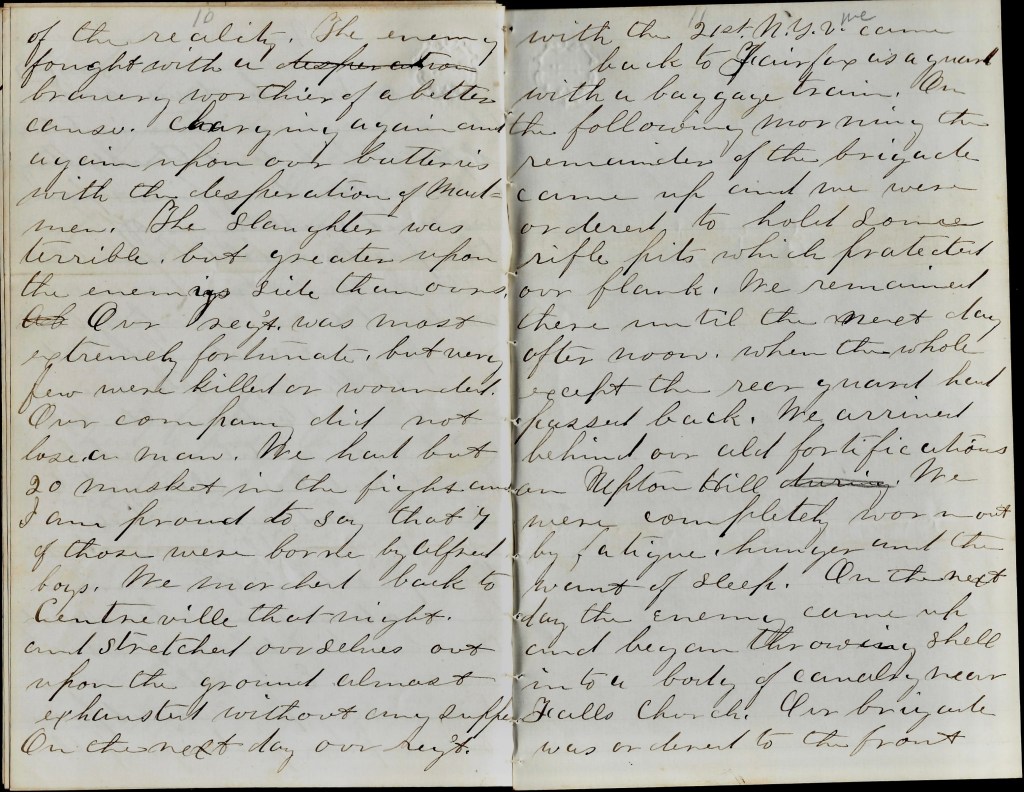

A retreat was ordered and we fell back in perfect order behind our batteries. The enemy continued to turn the left and not until our whole front had been changed to the left were our forces able to hold them in check. Our position after leaving the woods was one where nearly the whole field of conflict was in view. My pen would prove but a poor portrayer of the reality. The enemy fought with a bravery worthier of a better cause—charging again and again upon our batteries with the desperation of mad men. The slaughter was terrible but greater upon the enemy’s side than ours. Our regiment was most extremely fortunate—but very few were killed or wounded. Our company did not lose a man. We had but 20 muskets in the fight and I am proud to say that 7 of those were borne by Alfred [New York] Boys.

We marched back to Centreville that night and stretched ourselves out upon the ground almost exhausted without any supper. On the next day our regiment with the 21st New York Vols. came back to Fairfax as a guard with a baggage train. On the following morning the remainder of the brigade came up and we were ordered to hold some rifle pits which protected our flank. We remained there until the next day after noon when the whole except the rear guard had passed back. We arrived behind our old fortifications on Upton Hill. We were completely worn out by fatigue, hunger, and the want of sleep.

On the next day the enemy came up and began throwing shell into a body of cavalry near Falls Church. Our brigade was ordered to the front where it remained over night. On the night of the 6th inst. a large portion of the army came back across the Potomac and is now laying north of Washington, ready to be moved either way to confront Jackson if he shall dare to push a heavy force into Maryland or to protect Washington in the front if it shall be attacked there.

Pope—much to our satisfaction—has gone to the Northwest and McDowell, I trust, to his home. The restoration of McClellan to command has given a new confidence to the army. He is their favorite and they will fight under him as under no other man. Marching orders have just come and I must close. Receive this most hastily written correspondence from an old Oro. — S. Dexter

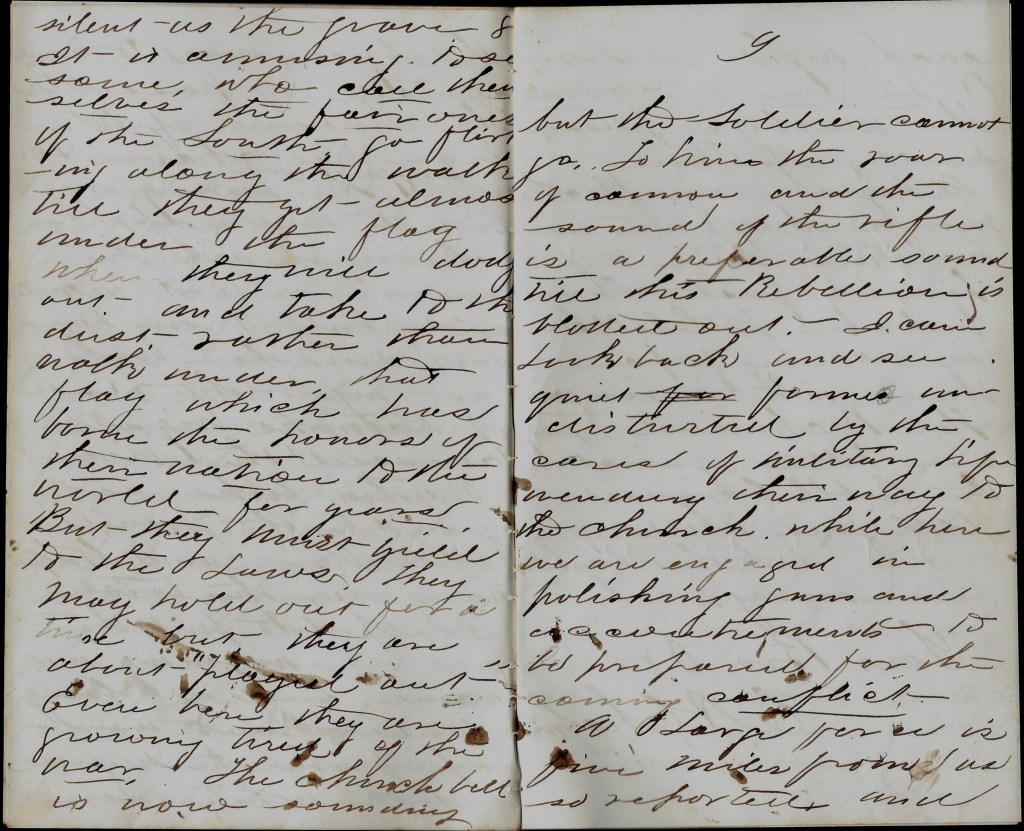

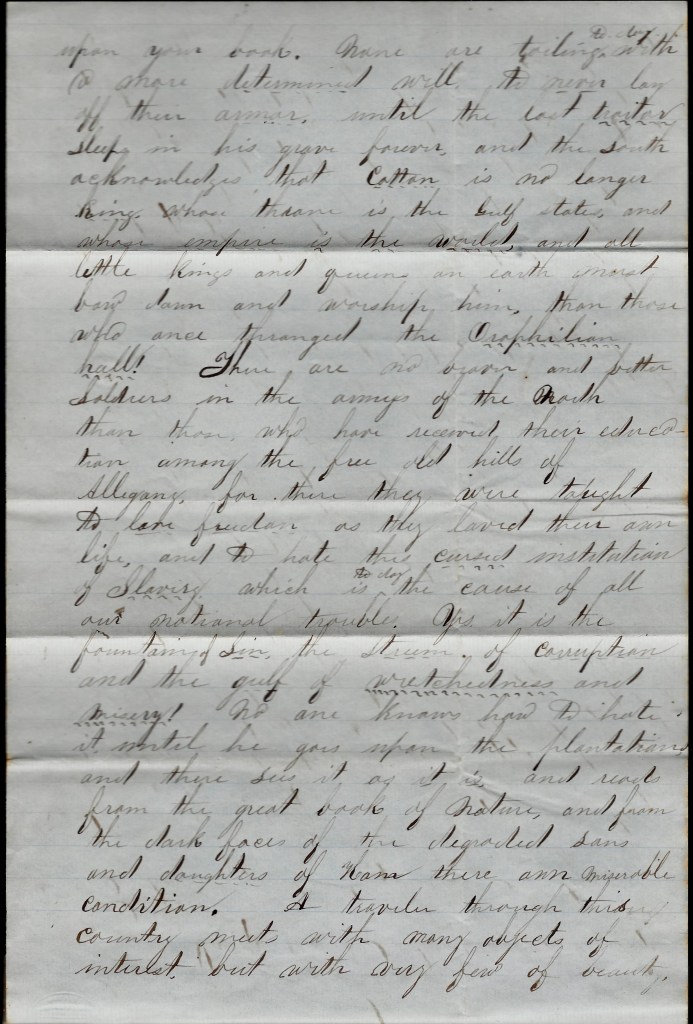

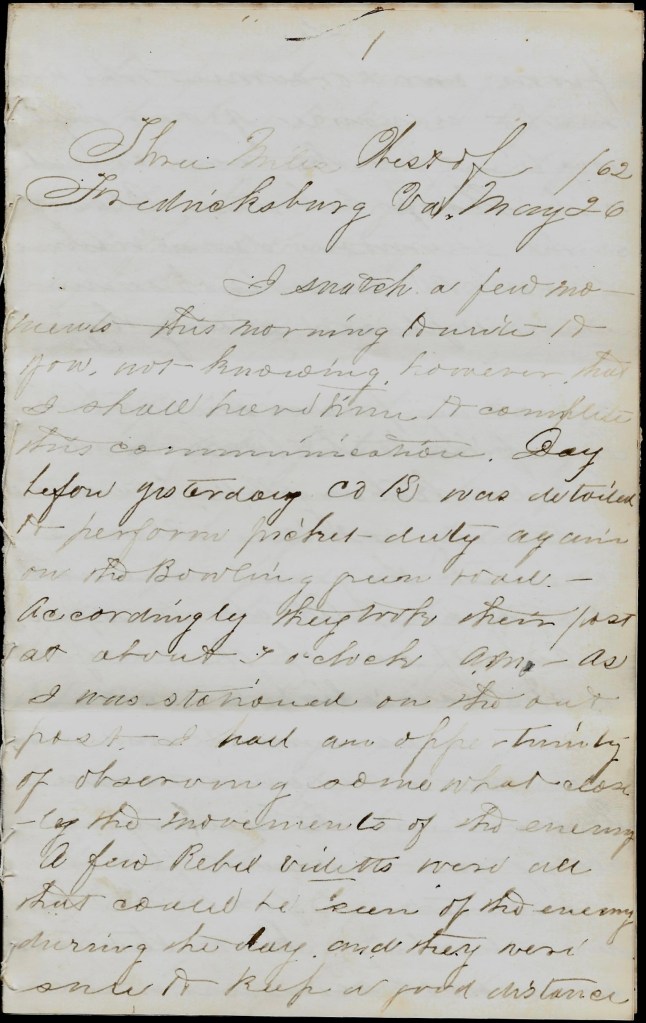

Letter 3

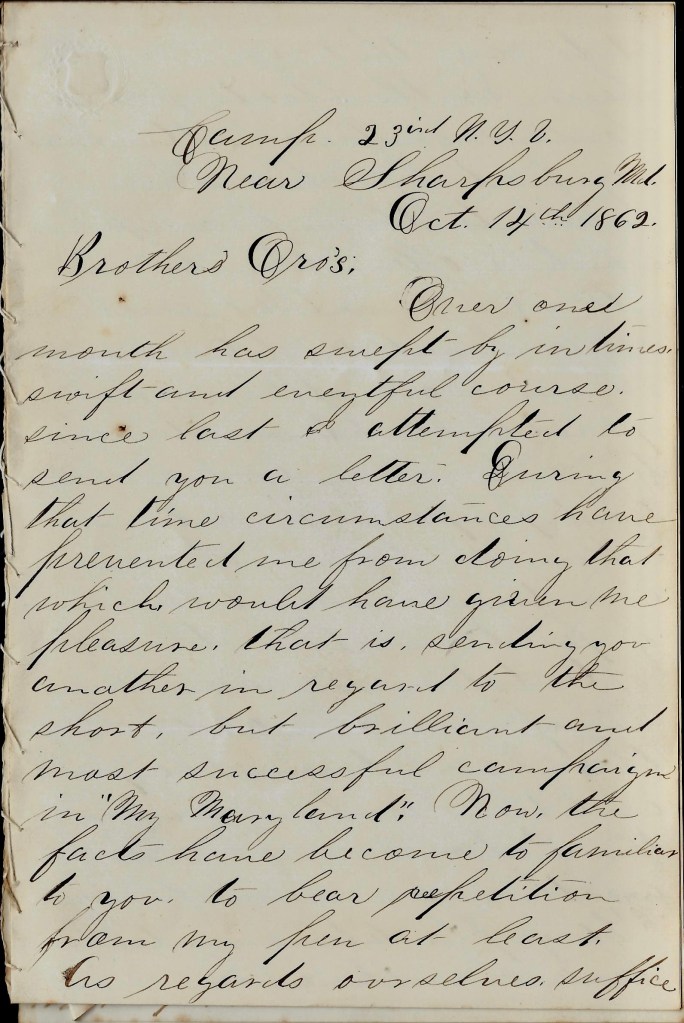

Camp 23rd New York Vol.

Near Sharpsburg, Maryland

October 14th 1862

Brothers Oro’s:

Over one month has swept by in time’s swift and eventful course since last I attempted to send you a letter. During that time, circumstances have prevented me from doing that which would have given me pleasure—that is, sending you another in regard to the short, but brilliant and most successful campaign in “My Maryland.” Now the facts have become too familiar to you to bear repetition from my pen at least. As regards ourselves, suffice it to say that your [lyceum] brothers here on the bloody fields of South Mountain and Antietam verified by action their fidelity to those principles which so often they have uttered within that well remembered and almost sacred room. Having been spared through those dangers, they are now in good health and prepared for future action in defense of our country’s honor and the cause of freedom.

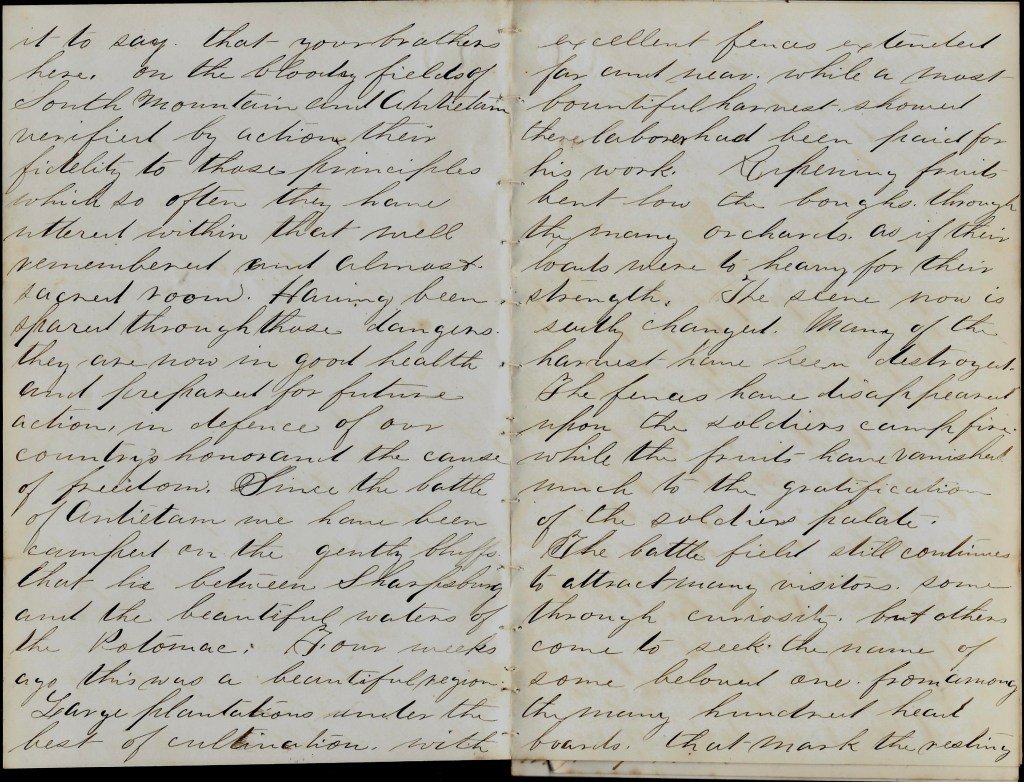

Since the Battle of Antietam, we have been camped on the gentle bluffs that lie between Sharpsburg and the beautiful waters of the Potomac. Four weeks ago this was a beautiful region—large plantations under the best cultivation with excellent fences extended far and near, while a most bountiful harvest showed their laborer had been paid for his work. Ripening fruits bent low the boughs through the many orchards as if their loads were too heavy for their strength. The scene now is sadly changed. Many of the harvest have been destroyed. The fences have disappeared upon the soldier’s camp fire while the fruits have vanished much to the gratification of the soldier’s palate.

The battlefield still continues to attract many visitors—some through curiosity, but other come to seek the name of some beloved one from among the many hundred head boards that mark the resting places of so many heroes and martyrs to their country’s cause who fell on that terrible and memorable day.

Our future stay at this place is uncertain. We have been under orders for some days to march at half an hour’s notice with two days rations and 100 rounds of ammunition. This to new troops would seem prophetic of deadly work not far in the future, but to us with our past experiences, it bears no such portent.

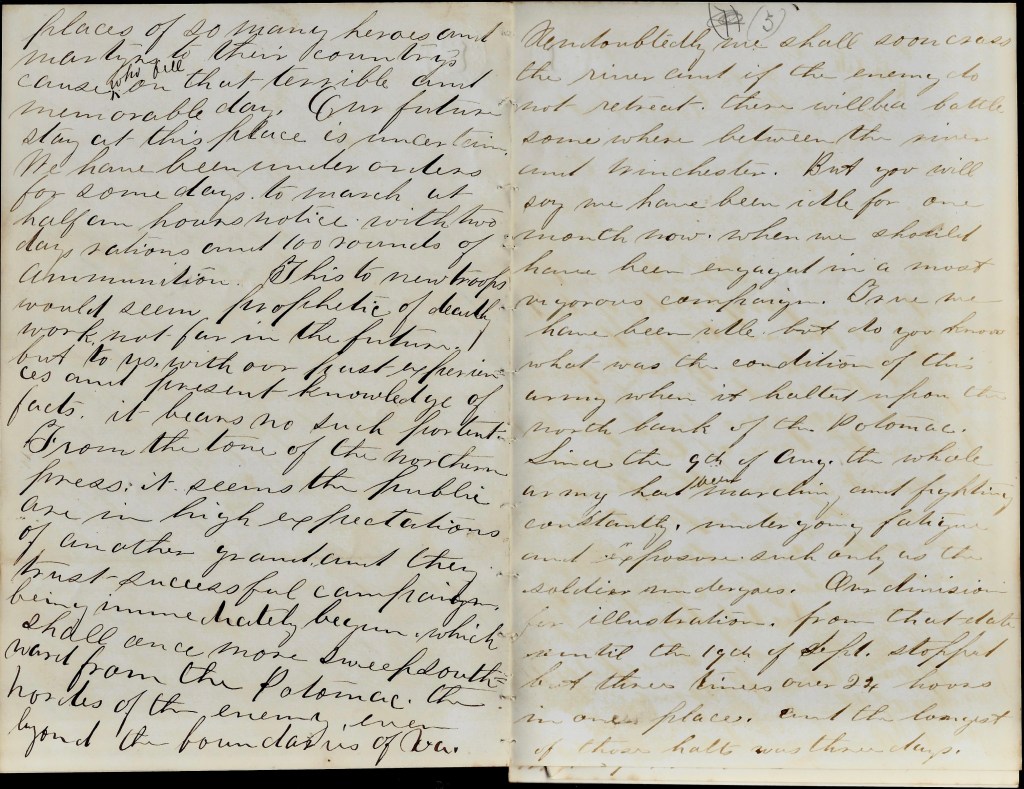

From the tone of the Northern press, it seems the public are in high expectations of another grand and, they trust, successful campaign being immediately begun which shall once more sweep southward from the Potomac, the hordes of the enemy ever beyond the boundaries of Virginia. Undoubtedly we shall soon cross the river and if the enemy do not retreat. there will be a battle somewhere between the river and Winchester. But you will say we have been idle for one month now when we should have been engaged in a most vigorous campaign. True, we have been idle. But do you know what was the condition of this army when it halted upon the north bank of the Potomac? Since the 9th of August the whole army had been marching and fighting constantly, undergoing fatigue and exposure such only as the soldier undergoes. Our division for illustration, from that date until the 19th of September, stopped but three times over 24 hours in one place and the longest of those halts was three days. We were constantly broke of our sleep while our food was scanty and irregular. When we entered the Battle of [2nd] Bull Run, we had been 60 hours with but 4 hours sleep and starvation really staring us in the face. Pope’s official report was true in that respect.

When we halted here, brigades were but regiments, and divisions but brigades. Our brigade numbered but 825 men for duty and Hatcher’s Brigade of five regiments did not number half that amount. And so it was throughout the whole army. All were dirty and be not shocked, most were lousy. We had not even found time and opportunities to wash our clothes. This remnant of the army was completely worn out like the horse that has lumbered all winter upon scanty fare. Could civilians, unless they believe a soldier is proof against fatigue and exposure, expect that such an army which had so nobly crowned its country’s banners with victory in her darkest hour should immediately, without rest, be sent into another campaign equally laborious? And because it has been delayed thus far already? Yes! Scarcely before the lightning messenger had ceased to transmit the details concerning the victories in Maryland, the northern Republican press began to heap its abuses upon Gen. McClellan because he did not immediately, without a halt, throw his decimated and worn-out columns across the Potomac.

As those expectations have been unrealized so far, so I think they will be in the future to a certain degree. You ask why. It is simple. Because the lateness of the season will not permit it. Four weeks more and it would be inhuman to ask troops to live in shelter tents and should they attempt it, not many weeks would elapse ere over one half the army would be on the sick list or in their graves. Four weeks more and the condition of the roads in Northern Virginia will be such that artillery and baggage trains cannot be moved except upon macadamized roads and these are not in sufficient numbers. Most surely that length of time at this season when no dependence can be placed upon the weather, is not sufficient to warrant the success of a movement as extensive as such an one must necessarily be.

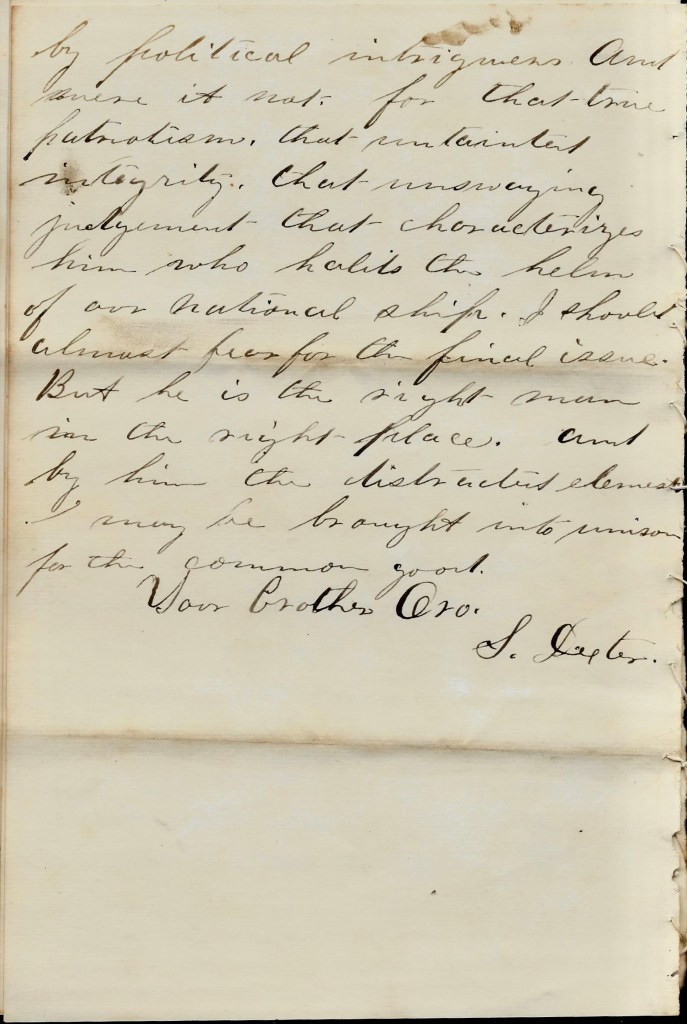

The military authorities know what an army could stand and because they ordered a halt, the radical press of the North with the N. Y. Tribune at the head, began anew to poison and distract the public mind by charging McClellan with incompetency. They belie facts and have belied every act of McClellan’s and that simply because he does not belong to their party politic. The whole race of New York editors would be but little safer in this army than in a rebel camp. It makes the heart of the true patriot in the field fighting for his country’s cause weep to see the public mind thus poisoned and distracted by political intriguers. And were it not for that true patriotism, that untainted integrity, that unswaying judgement that characterizes him who holds the helm of our national ship, I should almost fear for the final issue. But he is the right man in the right place and by him the distracted element may be brought into unison for the common good.

Your brother Oro., — S. Dexter

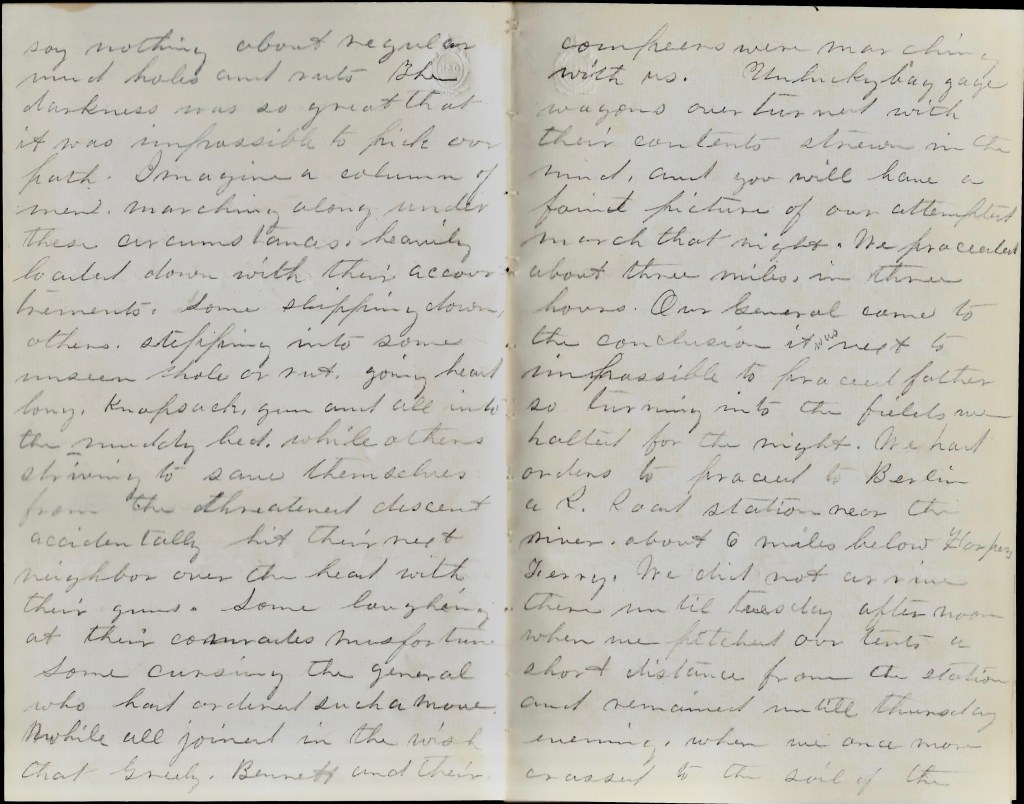

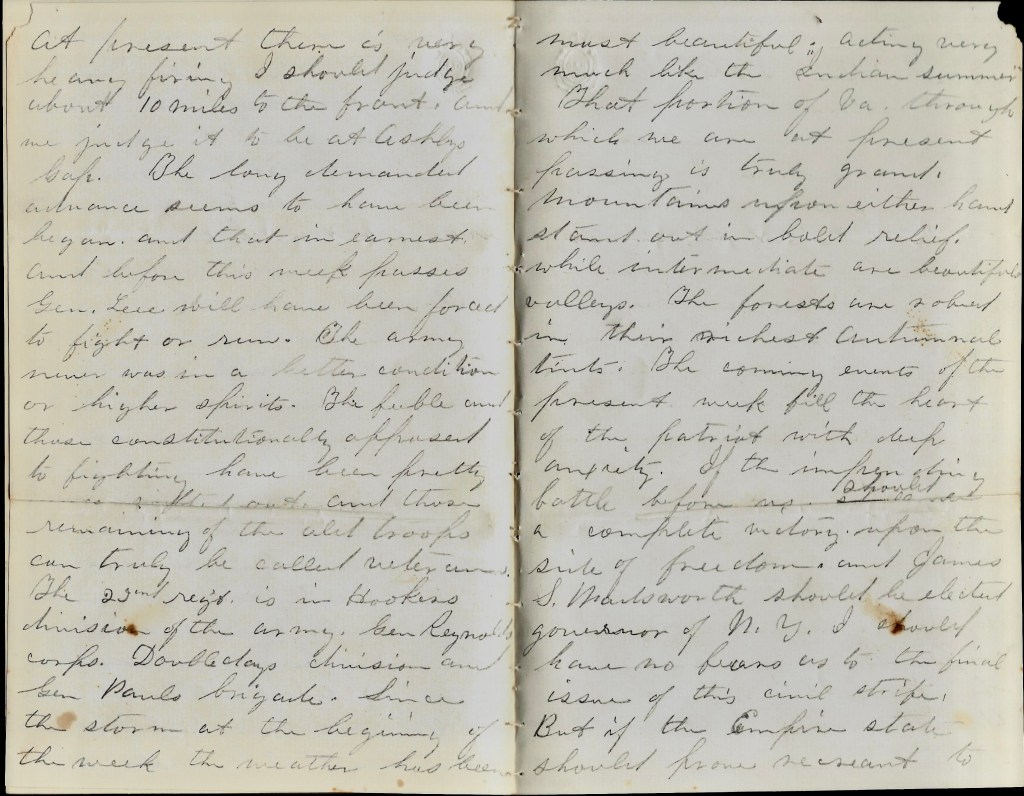

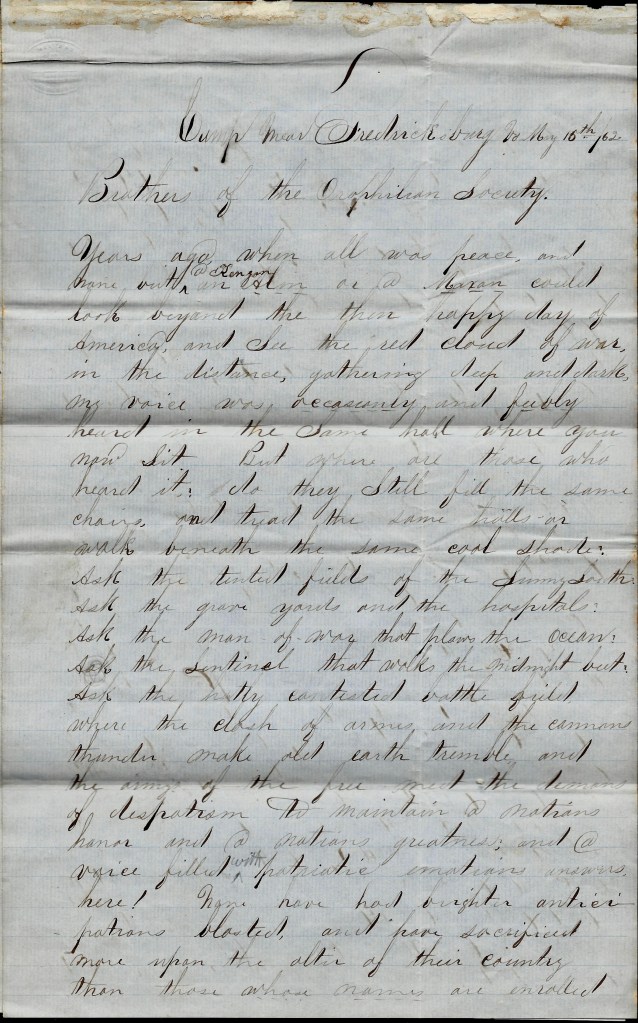

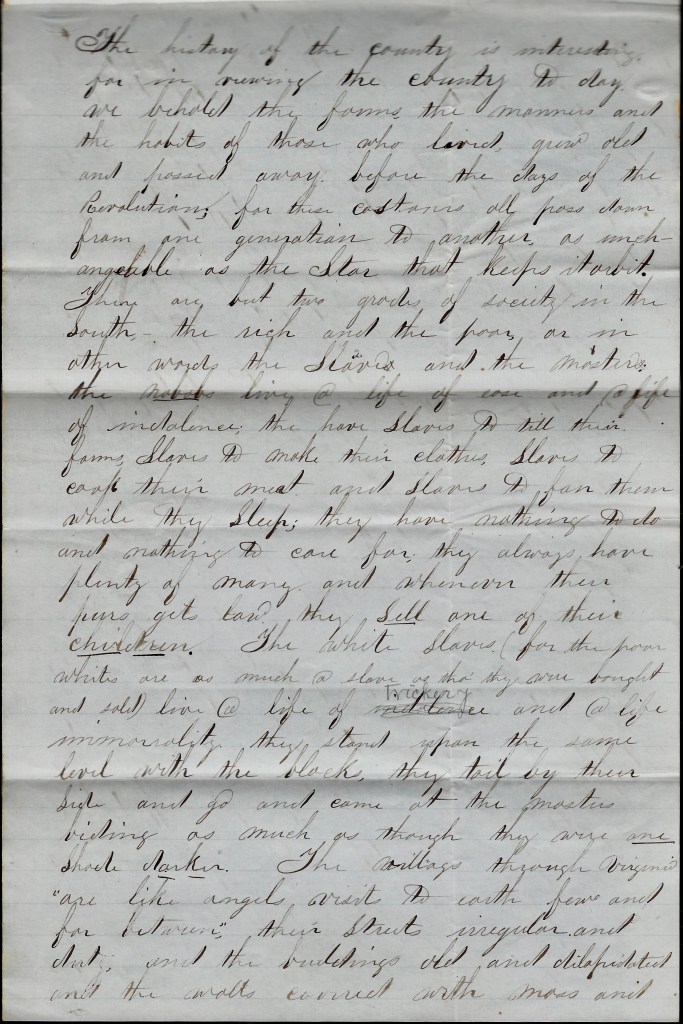

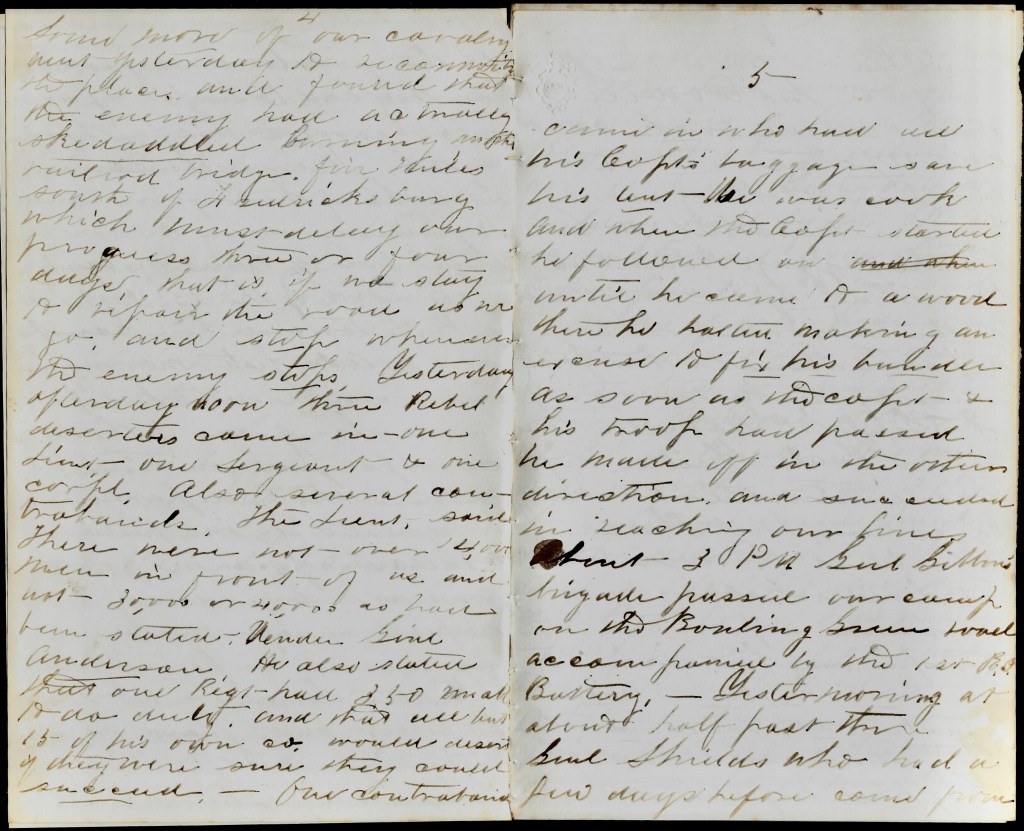

Letter 4

Purcellville, Va.

November 2, 1862

Brother Oro’s:

One week ago today as we sat huddled up in our tents, striving fruitlessly to be comfortable with a cold, windy, autumnal storm sweeping drearily over the land, orders came to march. It was after dark before we got under motion—the rest of the Division going ahead. We supposed we had experienced rough marching before and we expected it that night but it proved to be far beyond any of our former experiences. A constant rain of twelve hours together with the large amount of travel upon the roads had formed a mud pudding over shoe deep in most places, say nothing about the regular mud holes and ruts. The darkness was so great that it was impossible to pick our path. Imagine a column of men marching along under these circumstances, heavily loaded down with their accoutrements, some slipping down, others slipping into some unseen hole or rut, going head long, knapsacks, gun, and all into the muddy bed while others striving to save themselves from the threatened descent accidentally hit their next neighbor over the head with their guns. Some laughing at their comrades misfortune, some cursing the General who had ordered such a move, while all joined in the wish that [newspaper editors] Greeley, Bennett, and their compeers were marching with us.

Unlucky baggage wagons overturned with their contents strewn in the mud, and you will have a faint picture of our attempted march that night. We proceeded about three miles in three hours. Our General came to the conclusion it was next to impossible to proceed further so turning into the fields, we halted for the night. We had orders to proceed to Berlin—a railroad station near the river about 6 miles below Harpers Ferry. We did not arrive there until Tuesday afternoon when we pitched our tents a short distance from the station and remained until Thursday evening. When we once more crossed to the soil of the Old Dominion and proceeded about one mile beyond Lovettsville and bivouacked for the night. It was a beautiful evening and as we once more set foot upon the “sacred soil”, there was a feeling of humiliation to think that fifteen months ago we had crossed the same river for the same purpose and after thirteen months of occupation, we had been forced back by the foe whom we thought to reduce.

On the following morning we were mustered for pay and in the afternoon moved for want about one mile farther. And yesterday moved forward to this place which is a small hamlet situated on the pike leading from Leesburg to Winchester. Snicker’s Gap, the point where the pike crosses the mountains that lay between us and Winchester, is about six miles distant and is said now to be in our possession. Our advance cavalry under Gen. Pleasanton drove the enemy’s cavalry from this vicinity yesterday and took one piece of their artillery.

While we were coming forward, the roar of their guns gave us music to march by. Quite early this morning there was cannonading abour six miles to the front that soon ceased and very distant cannonading could be heard in the direction of Thoroughfare Gap. We suppose that to be Siegel. At present there is very heavy firing I should judge about 10 miles to the front and we judge it to be at Ashby’s Gap.

The long demanded advance seems to have been begun and that in earnest. And before this week passes, Gen. Lee will have been forced to fight or run. The army never was in a better condition or higher spirits. The feeble and those constitutionally opposed to fighting have been pretty well sifted out and those remaining of the old troops can truly be called veterans. The 23rd Regt. is in Hooker’s Division of the army. Gen. Reynolds Corps, Doubleday’s Division and Gen. Paul’s Brigade.

Since the storm at the beginning of the week, the weather has been most beautiful, acting very much like the “Indian Summer.” That portion of Virginia through which we are at present passing is truly grand. Mountains upon either hand stand out in bold relief while intermediate are beautiful valleys. The forests are robed in their richest autumnal tints. The coming events of the present week fill the heart of the patriot with deep anxiety. If the impending battle before us should be a complete victory upon the side of freedom and James S. Wadsworth should be elected Governor of New York, I should have no fears as to the final issue of this civil strife. But if the Empire State should prove recreant to the man whom she helped place in the executive chair in this his most trying hour, I shall feel like disowning her as my native state. Add to this political defeat another defeat in our army now advancing and I should despair of success. Time alone shall be the revelation of the issue which now is known only to Him “who rules the destinies of nations.”

Yours in haste, – S. Dexter