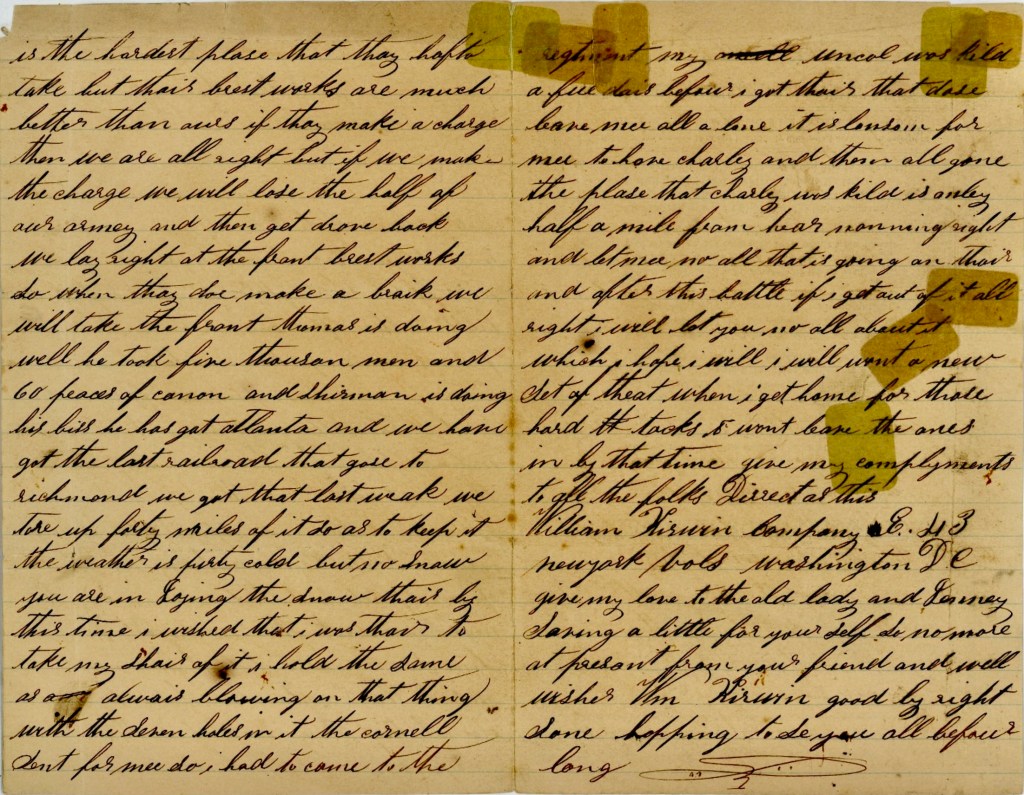

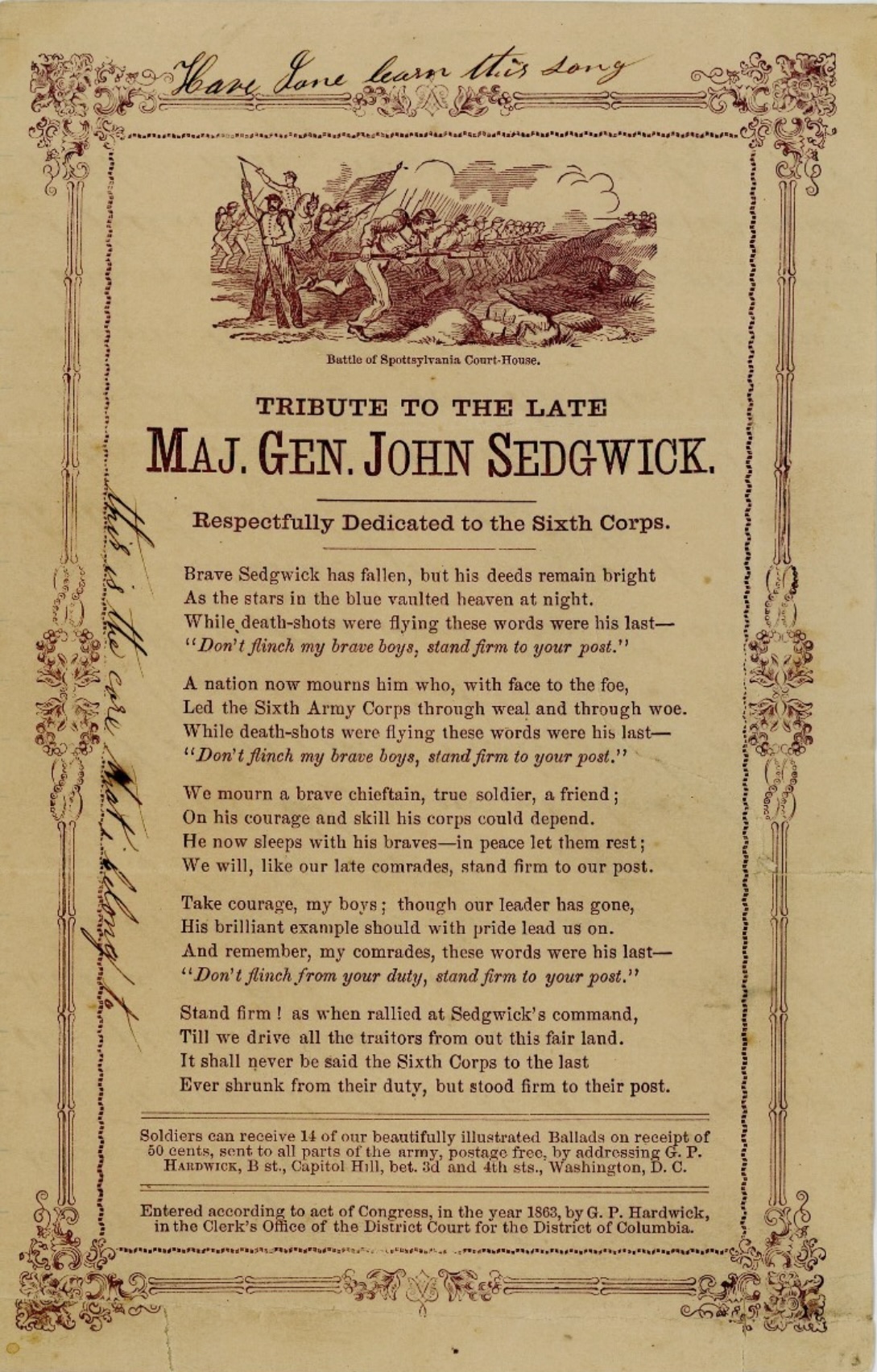

The following letter was written by William H. Kirwin (1839-1917) who enlisted at Troy, New York as private, Co. E , 43rd New York Infantry on 30 December 1863; appointed musician and returned to ranks sometime after February 1865; mustered out with company, June 27, 1865, at Washington, D. C. While he was in the service, he was described as 5′ 8″ inches tall, with gray eyes and brown hair.

William was the son of William and Esther (Rasper) Kirwin. He was educated In the public schools of Troy and his first business in which he was engaged was that of groceryman. At one time he was one of the best known horsemen in this section and for the last seventeen years had been Superintendent of the Lansingburgh Waterworks.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

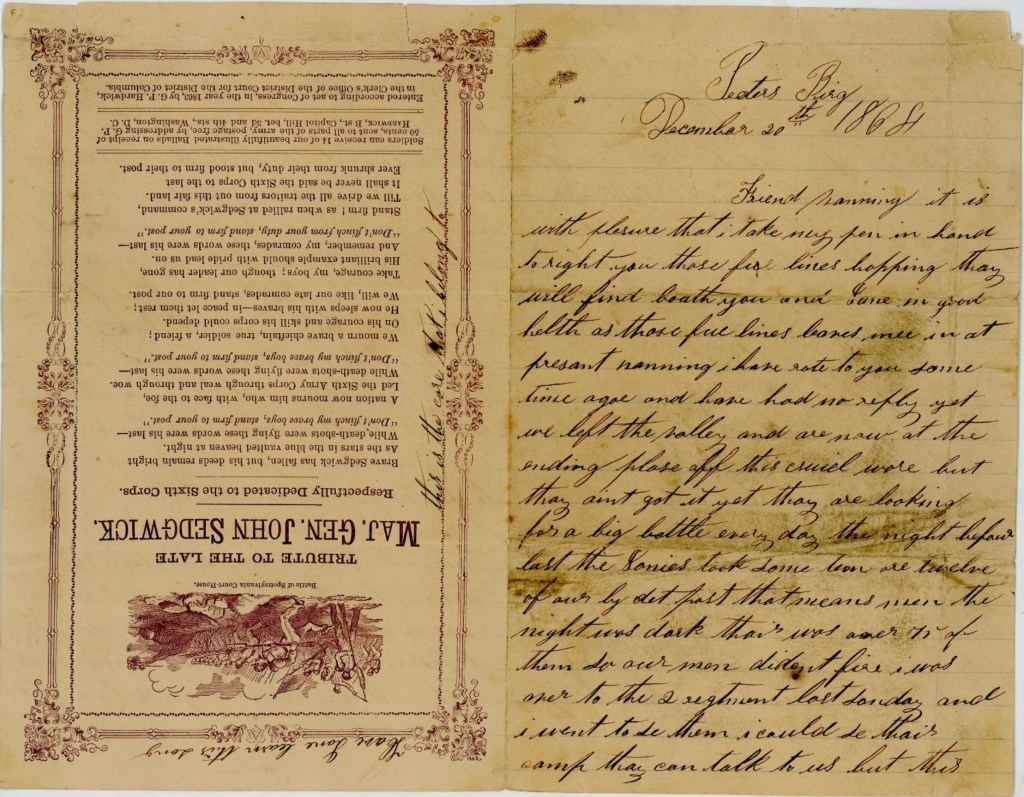

Petersburg

December 20, 1864

Friend Nanning,

It is with pleasure that I take my pen in hand to write you these few lines hoping they will find both you and Jane in good health as these few lines leaves me in at present. Nanning, I have wrote to you some time ago and have had no reply yet.

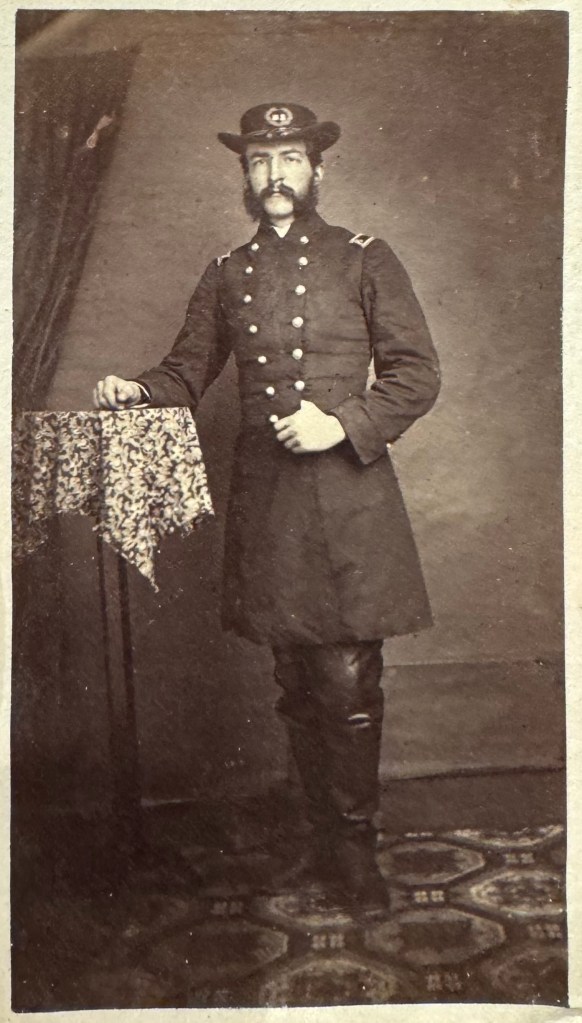

We left the Valley and are nowat the ending place of this cruel war but they ain’t got it yet. They are looking for a big battle every day. The night before last the Johnnies took some ten or twelve of our outpost—that means men. The night was dark. There was over 75 of them so our men didn’t fire. I was over to the 2nd Regiment last Sunday and I went to see them. I could see their camp. They can talk to us but this is the hardest place that they have to take but their breastworks are much better than ours. If they make a charge, then we are all right. But if we make the charge, we will lose the half of our army and then get drove back. We lay right at the front breastworks so when they do make a break, we will take the front.

Thomas is doing well. He took five thousand men and 60 pieces of cannon and Sherman is doing his biss [business]. He has got Atlanta and we have got the last railroad that goes to Richmond. We got that lastweek. We tore up forty miles of it so as to keep it.

The weather is pretty cold but no snow. You are enjoying the snow there by this time. I wished that I was there to take my share of it.

I hold the same as always, blowing on that thing with the siren holes in it [bugle]. The Colonel sent for me so I had to come to the regiment. My uncle was killed a few days before I got there. That does leave me all alone. It is lonesome for me to have Charley and them all gone. The place that Charley was killed is only half a mile from here.

Nanning, write and let me know all that is going on there and after this battle, if I get out of it all right, I will let you know all about it which I hope I will. I will want a new set of teeth when I get home for those hard tacks won’t cave the ones in by that time. Give my compliments to all the folks.

Direct as this: William Kirwin, Company E, 43rd New York Vols., Washington D. C.

Give my love to the old lady and Jenny, saving a little for yourself. So no more at present. From your friend and well wisher, — Wm. Kirwin

Goodby. Write soon. Hoping to see you all before long.