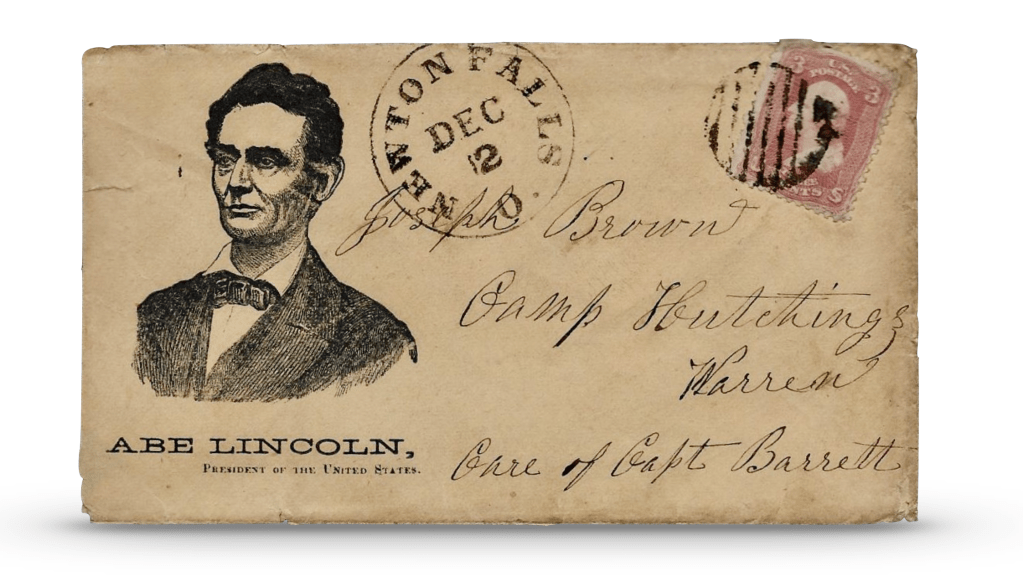

The following was written by Eberle Benton Underwood (1839-1925), the son of Willin Underwood (1800-1872) and Lovisa Rawson (1819-1844) of New Baltimore, Stark county, Ohio. Before and after the war, Eberle worked as a painter but during the Civil War he served as a private in Co. B, 6th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry (OVC).

After spending the winter of 63-64 fighting Mosby’s guerrillas, in the spring of 1864 the 6th OVC joined Ulysses S. Grant’s movement on Richmond, participating in several battles while serving in the Cavalry Corps, under Gen. Philip H. Sheridan. It was involved in the Union cavalry operations during the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg, as well as taking part in the Battle of Trevillian Station. In 1865, the regiment was in the Battle of Five Forks, and during the Appomattox Campaign, in the Battle of Sayler’s Creek. The 6th Ohio Cavalry marched in the Grand Review of the Armies in May 1865, and then exited service at Petersburg, Virginia, on August 7, 1865. During its term of service, the 6th Ohio Cavalry lost 5 officers and 52 enlisted men killed and mortally wounded, and 4 officers and 177 enlisted men by disease, for a total of 238 fatalities. More than 1700 men served in the ranks at various times, however, the field strength of the regiment rarely exceeded 500 men at any given time.

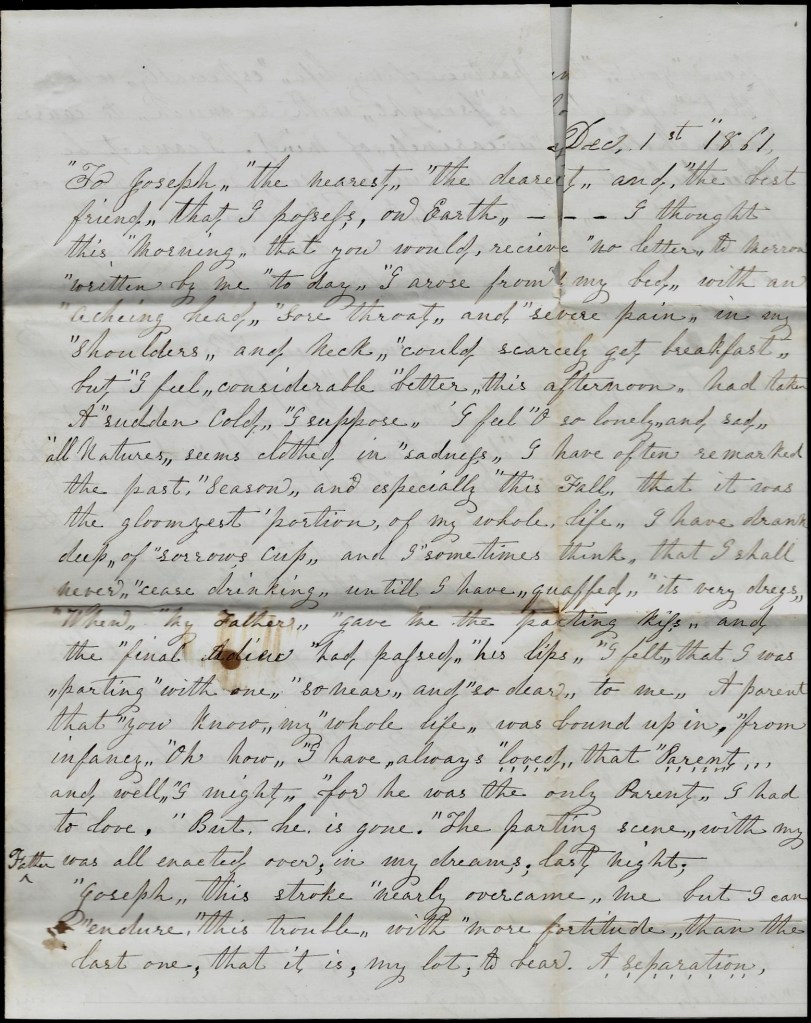

Eberle wrote the letter to his sister Nellie Louise (Underwood) Stanford (1842-1921), the widow of Vactor (“Van”) B. Stanford (1837-1864 who died on 5 June 1864 at Chattanooga, Tennessee. Van served in Battery A, 1st Ohio Light Artillery. After reenlisting for three more years, and marrying Nellie while at home on Veteran’s furlough in February 1864, Van was with Sherman’s army in the march on Resaca, Georgia, when he was severely wounded by a premature discharge of his cannon. He lingered for three weeks before he died.

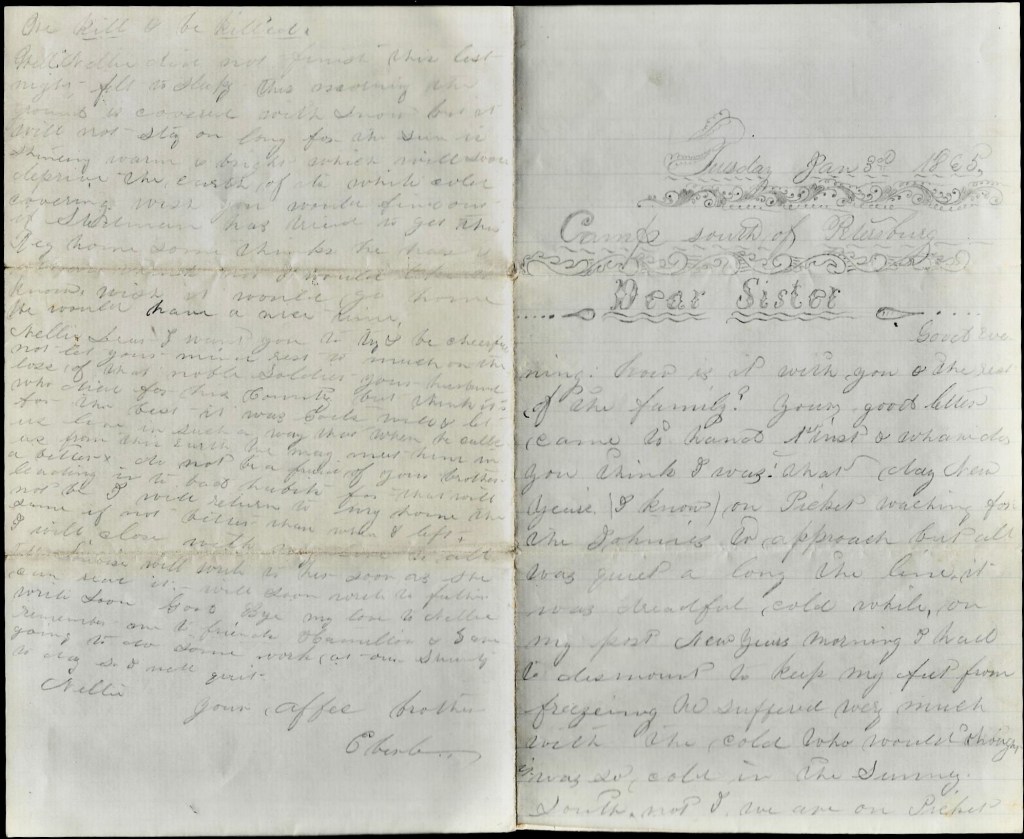

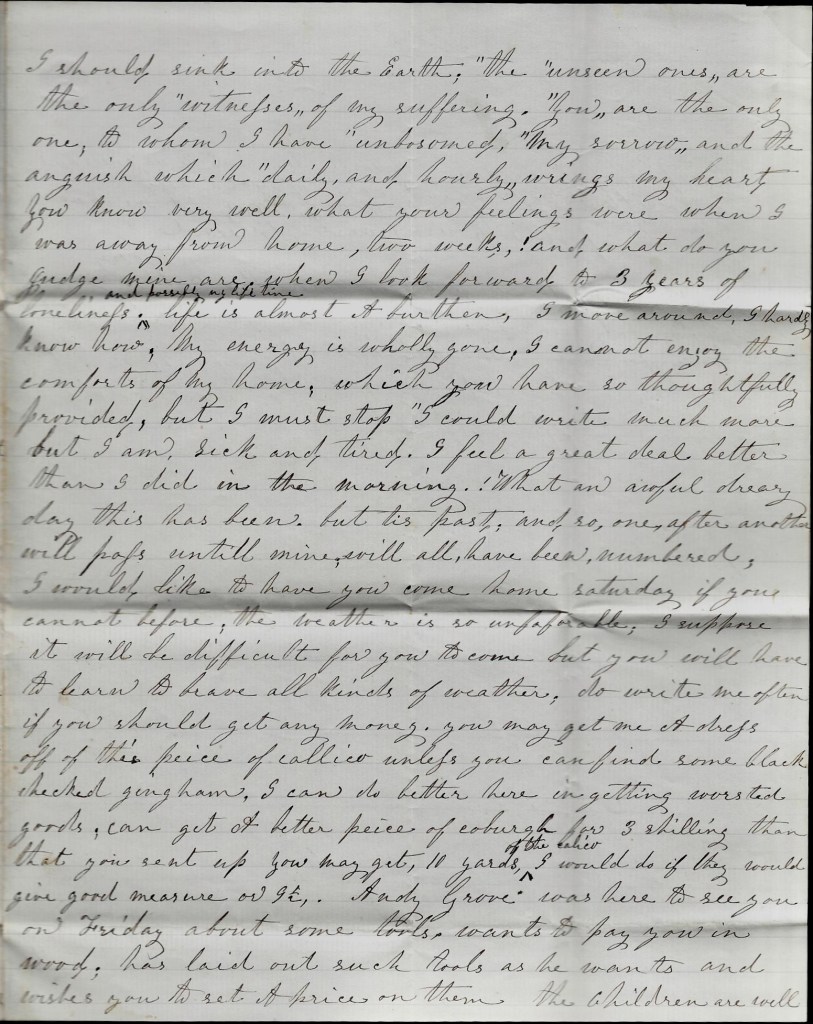

Transcription

Camp south of Petersburg

Tuesday, January 30, 1865

Dear Sister,

Good evening. How is it with you and the rest of the family? Your good letter came to hand 1st inst. & where do you think I was that day—New Years? I know, on picket, watching for the Johnnies to approach. But all was quiet along the line. It was dreadful cold while on my post. New Years morning I had to dismount to keep my feet from freezing. We suffered very much with the cold. Who would of thought it was so cold in the Sunny South? Not I.

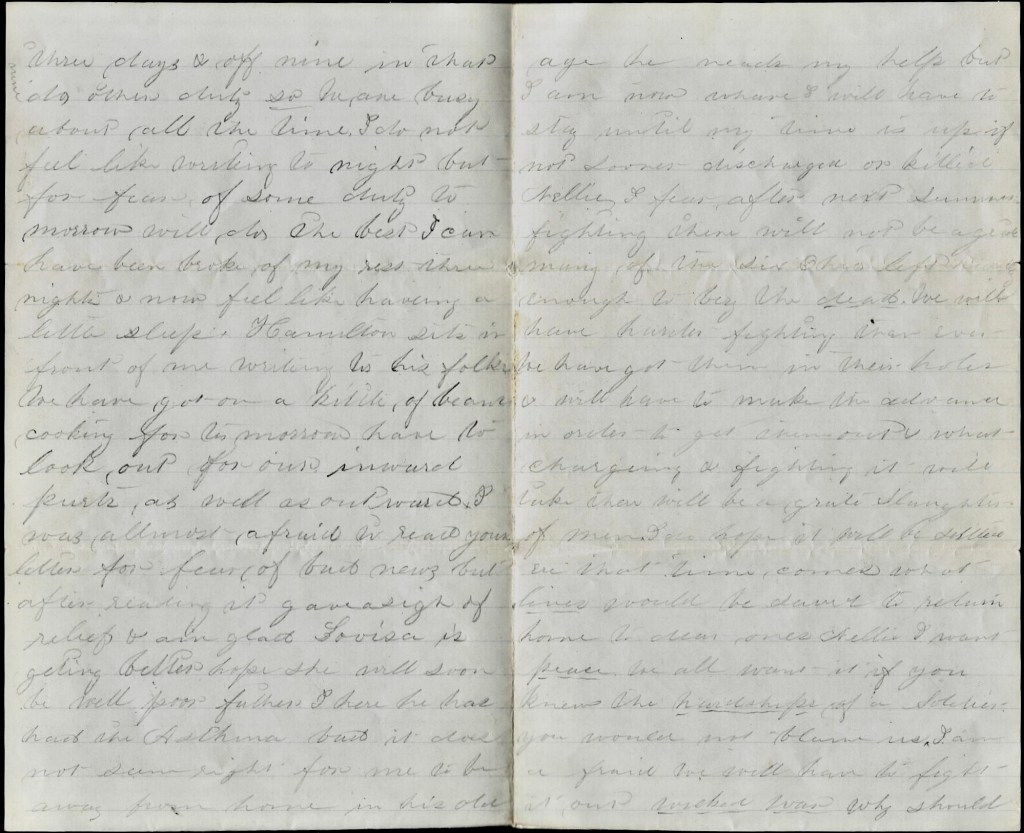

We are on picket three days and off nine. In that time we do other duty so we are busy about all the time. I do not feel like writing tonight but for fear of some duty tomorrow, will do the best I can. Have been broke of my rest three nights & now feel like having a little sleep. Hamilton sits in front of me writing to his folks. We have got a kettle of beans cooking for tomorrow. Have to look out for our inward parts as well as outward.

I was almost afraid to read your letter for fear of bad news but after reading it gave a sigh of relief & am glad Lovisa is getting better. Hope she will soon be well. Poor father, I hear he has had the asthma but it does not seem right for me to be away from home in his old age. He needs my help but I am now where I will have to stay until my time is up, if not sooner discharged or killed.

“I fear after next summer’s fighting there will not be a great many of the Sixth Ohio left—barely enough to bury the dead. We will have harder fighting than ever. We have got them in their holes & will have to make the advance in order to get them out…it will be a great slaughter of men.”

— Pvt. Eberle Underwood, Co. B, 6th OVC, near Petersburg 1.30.65

Nellie, I fear after next summer’s fighting there will not be a great many of the Sixth Ohio left—barely enough to bury the dead. We will have harder fighting than ever. We have got them in their holes & will have to make the advance in order to get them out & what charging & fighting it will take then will be a great slaughter of men. I do hope it will be settled ere that time comes. What lives would be saved to return home to dear ones.

Nellie, I want peace. We all want it. If you knew the hardships of a soldier you would not blame us. I am afraid we will have to fight it out. Wicked war! Why should we kill & be killed?

Well, Nellie, I did not finish this last night. Fell to sleep. This morning the ground is covered with snow but it will not stay on long for the sun is shining warm & bright which will soon deprive the earth of the white cold covering. Wish you would find out if [Col. William] Stedman has tried to get this regiment home. Some thinks he has and some think not. I would like to know. Wish it would go home. We would have a nice time.

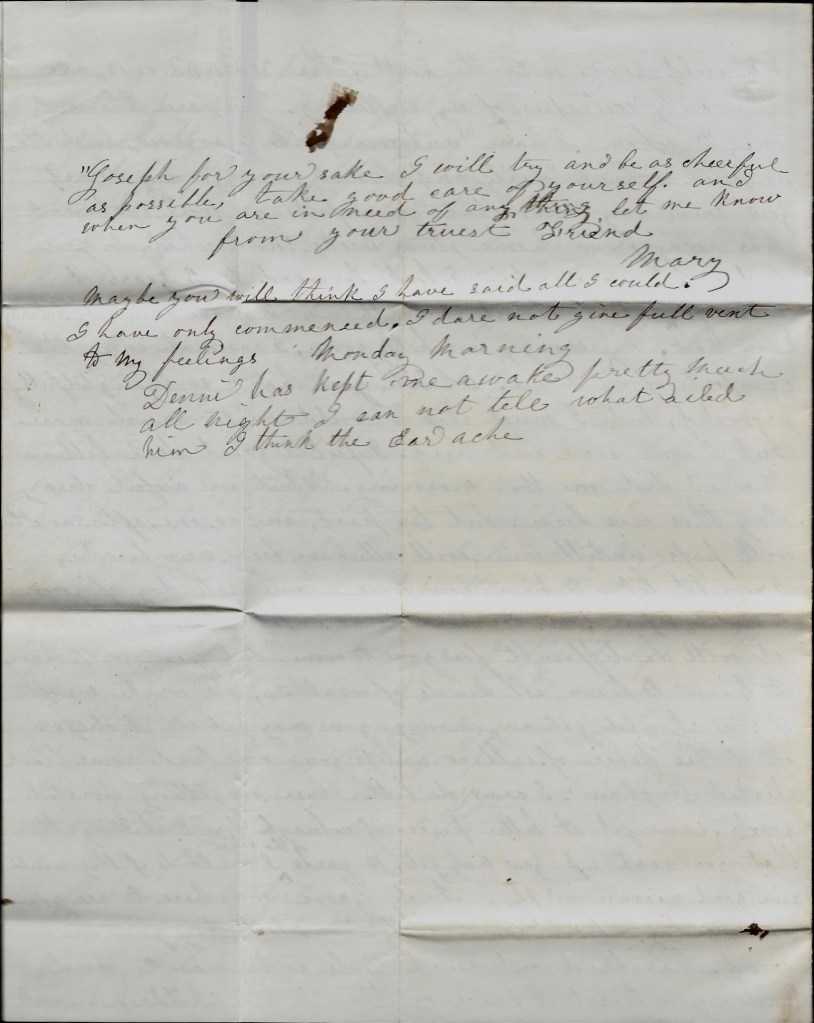

Nellie dear, I want you to try and be cheerful and not let your mind rest too much on the loss of that noble soldier—your husband—who died for his country. But think it’s for the best. I was God’s will & let us live in such a way that when He calls us from this earth, we may meet Him in a better [world]. Do not be afraid of your brother leading into bad habits for that will not be. I will return to my home the same, if not better than when I left.

I will close with my love to all. Tell Lovisa I will write to her soon as she can read it. Will son write to Father. Write soon. Goodbye. My love to Nellie. Remember me to friends. Hamilton & I are going to do some work on our shanty today so I will quit.

Your affectionate brother, — Eberle