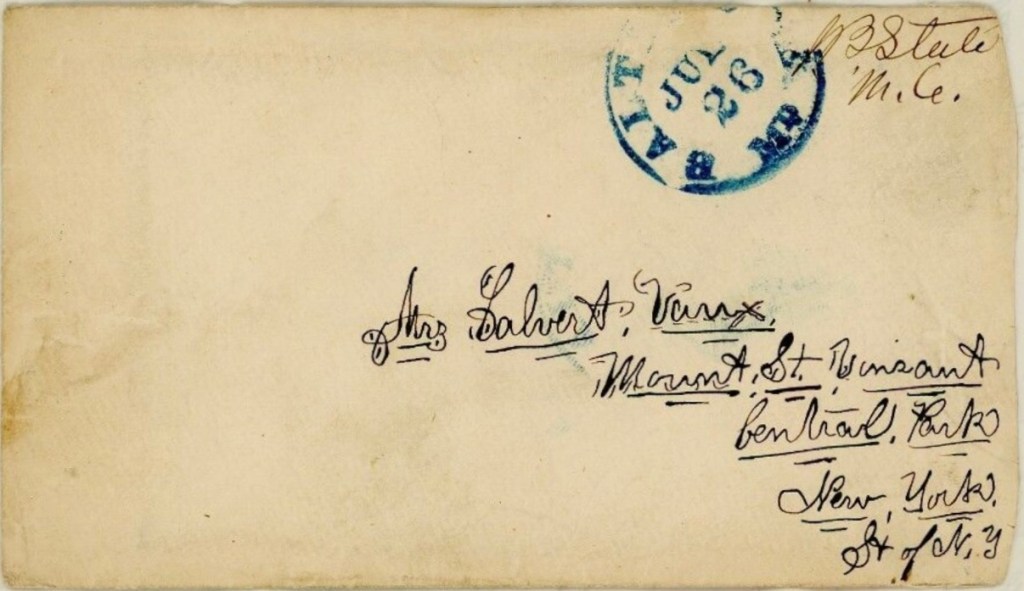

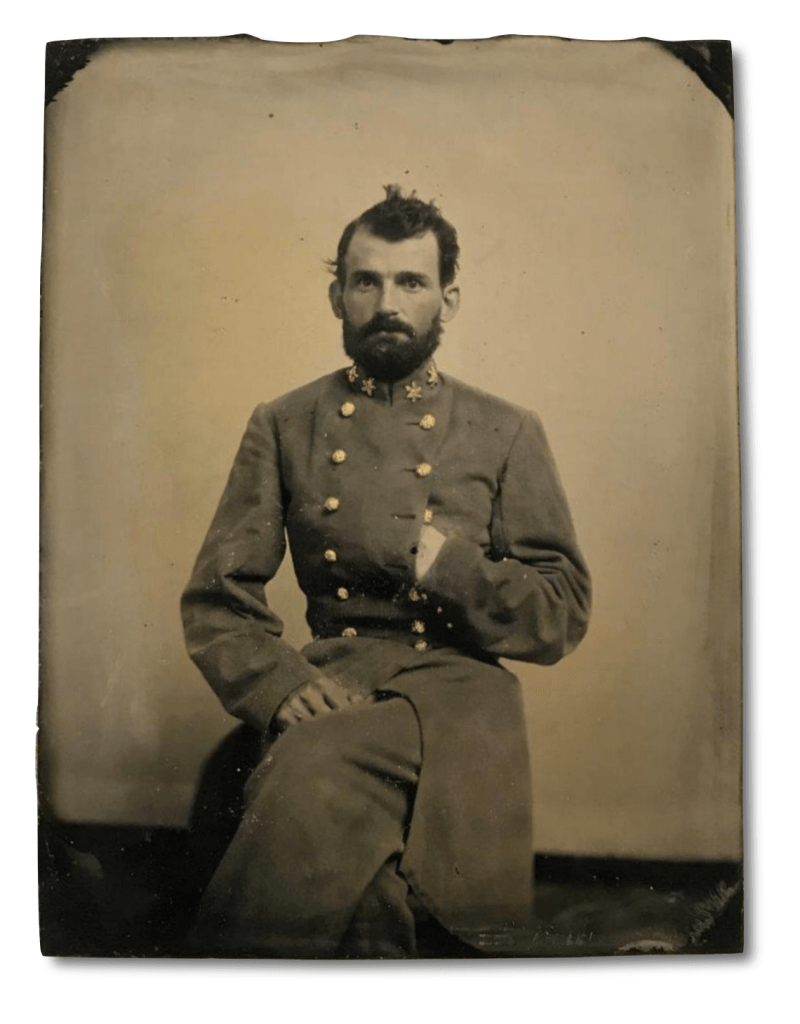

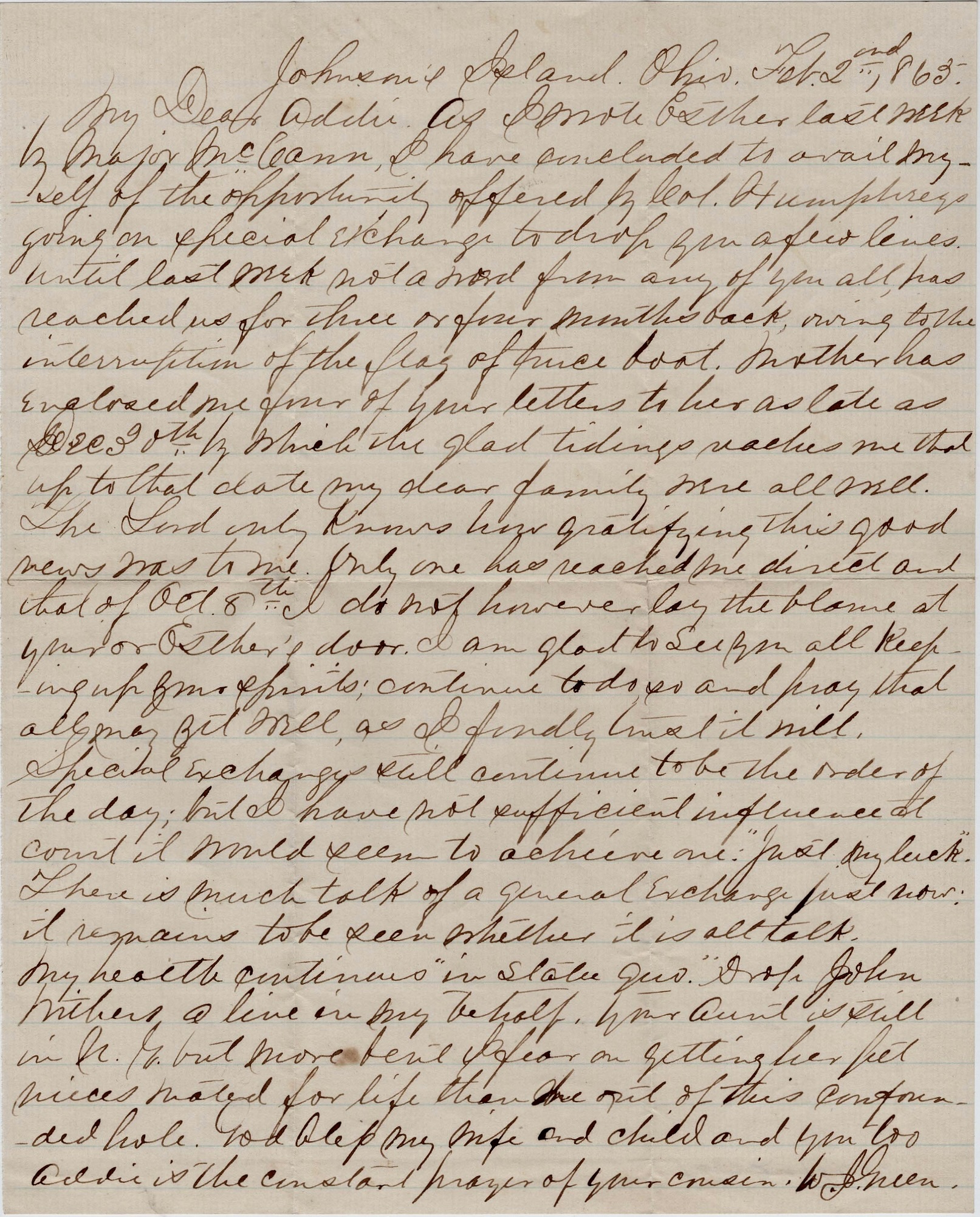

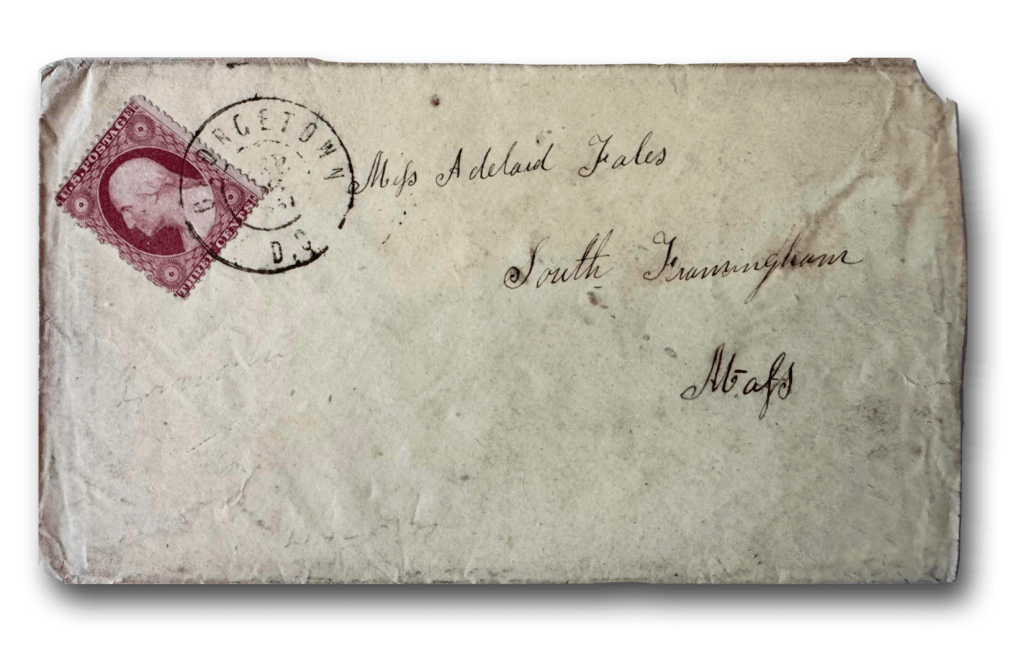

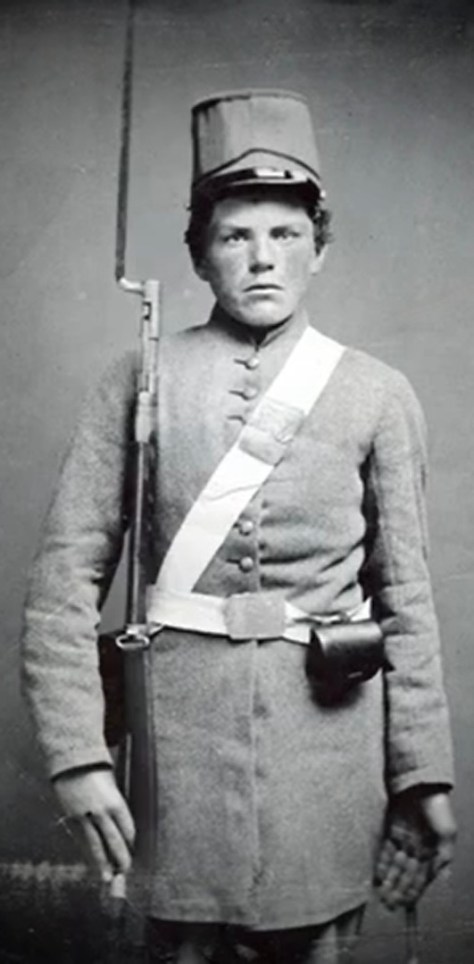

The following letter was written by Stephen H. Hagadorn (1836-1881), the son of Dr. Stephen Hagadorn (1818-1863) and Angeline Hagadorn (1815-1842) of Bath, Steuben county, New York. Stephen left his parents home sometime after the 1860 US Census and relocated to Wisconsin whereupon he was swept up in patriotism and enlisted in Co. K, 2nd Wisconsin Infantry. The regiment was quickly outfitted, the men issued state militia grey uniforms, and sent east in time to participate in the Battle of Blackburn’s Ford and Bull Run. In this letter to his father, Stephen described in detail the 18 July 1861 Battle of Blackburn’s Ford in which his regiment actually played only a minor role as a reserve regiment in Gen. William T. Sherman’s Brigade. Tragically, two days later in the Battle of Bull Run, their grey uniforms inadvertently exposed them to take friendly fire, resulting in Stephen being wounded and captured.

Stephen’s pension record informs us that he served in two different regiments during the Civil War. After he was exchanged as a prisoner of war and recovered from his wound, he transferred on 8 December 1861 into Co. A, 1st Wisconsin Heavy Artillery and served with that unit until 11 February 1863 when he was discharged. After he was discharged, Stephen enrolled as a medical student as the University of Michigan and became a physician, like his father. Stephen took up practice in Portsmouth, Bay county, Michigan, until 9 October 1881 when he died by drowning in the Saginaw river while on his way to make a house call. He fell overboard from the ferry boat transporting him across the river when he suffered an epileptic seizure—a condition that plagued him all his life apparently. He left a wife and 13 year old son.

Ironically, Stephen’s father was also taken a prisoner in the Battle of Bull Run though he was not a soldier. He was held until at least mid November 1861 as the extensive correspondence titled, “The Case of Dr. Stephen Hagadorn” will show, which I summarize by extracting the following statement by Dr. Hagadorn written to the CSA War Department: “I left my home and business on the 17th of July to return as soon as the 27th. Did not come as an invader, having no weapons of any kind. I am in the fiftieth year of my age; am a physician, Stephen Hagadorn by name, and live at Bath, Steuben County, N.Y. I came only to see a son who had enlisted in Wisconsin. Found on Sunday that a battle was being fought. Anxious as a father could be to know whether my son was alive, was too venturesome, consequently am a prisoner. My son is a prisoner here and must of course be held as such until disposed of. I ask mercy at your hands, and a release that I may go to my distressed family. When taken I was robbed of over $100 in money and papers that were valuable to me, and am as unpleasantly sisuated as mortal man can be on account of being detained from my family, who of course must be much distressed on account of my absence. Will you, my dear fellow-beings, let me go I pray you? I have done nothing to offend you therefore I pray you let me go.”

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

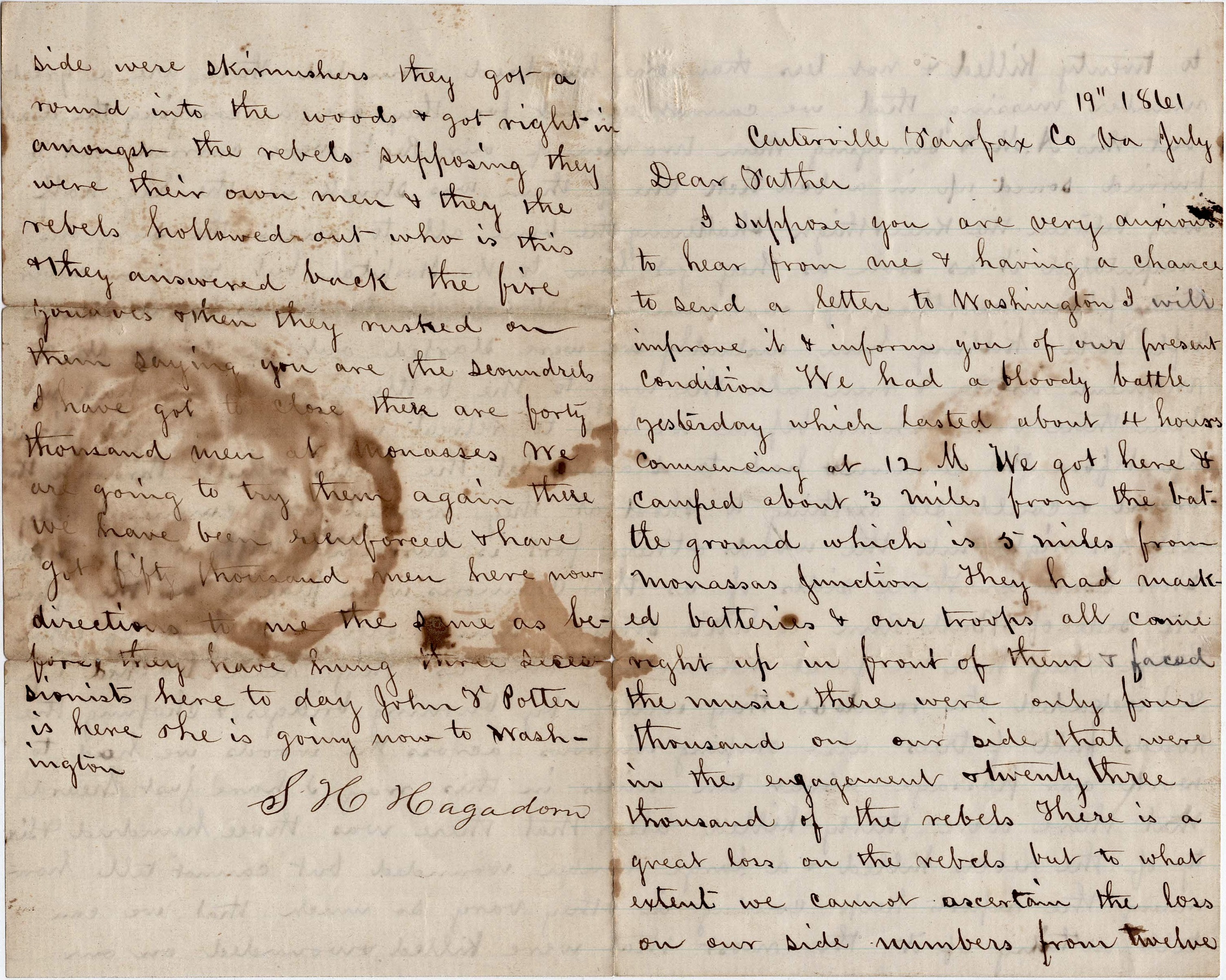

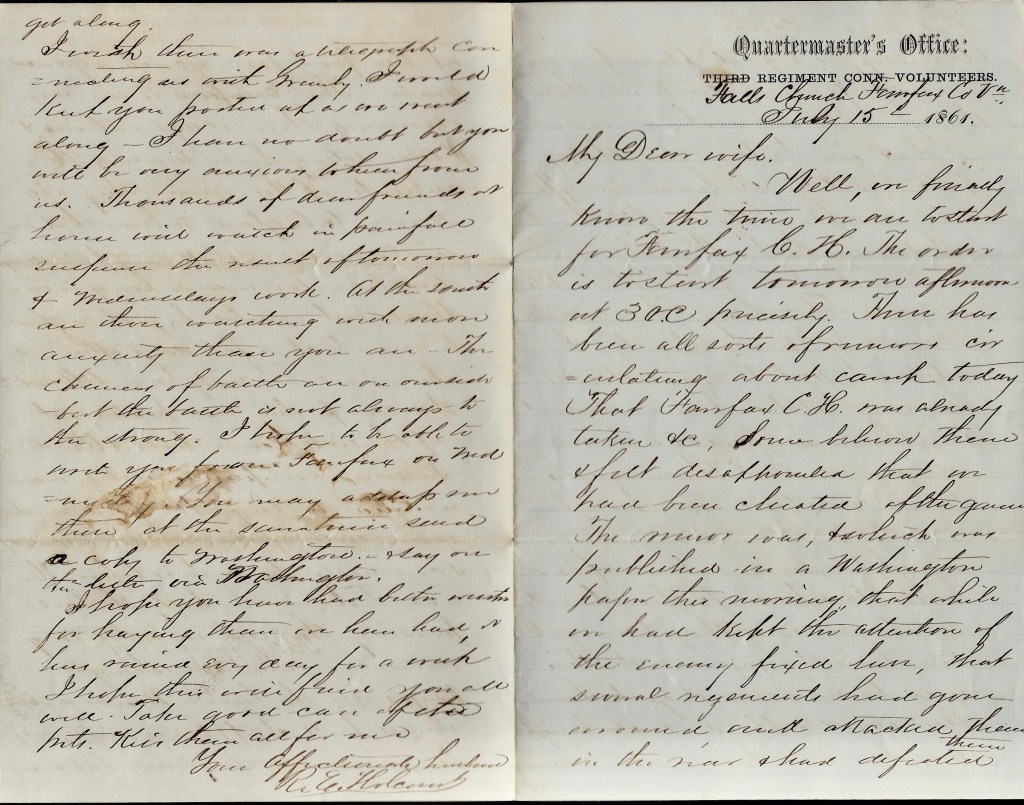

Centerville, Fairfax Co., Virginia

July 19th 1861

Dear Father,

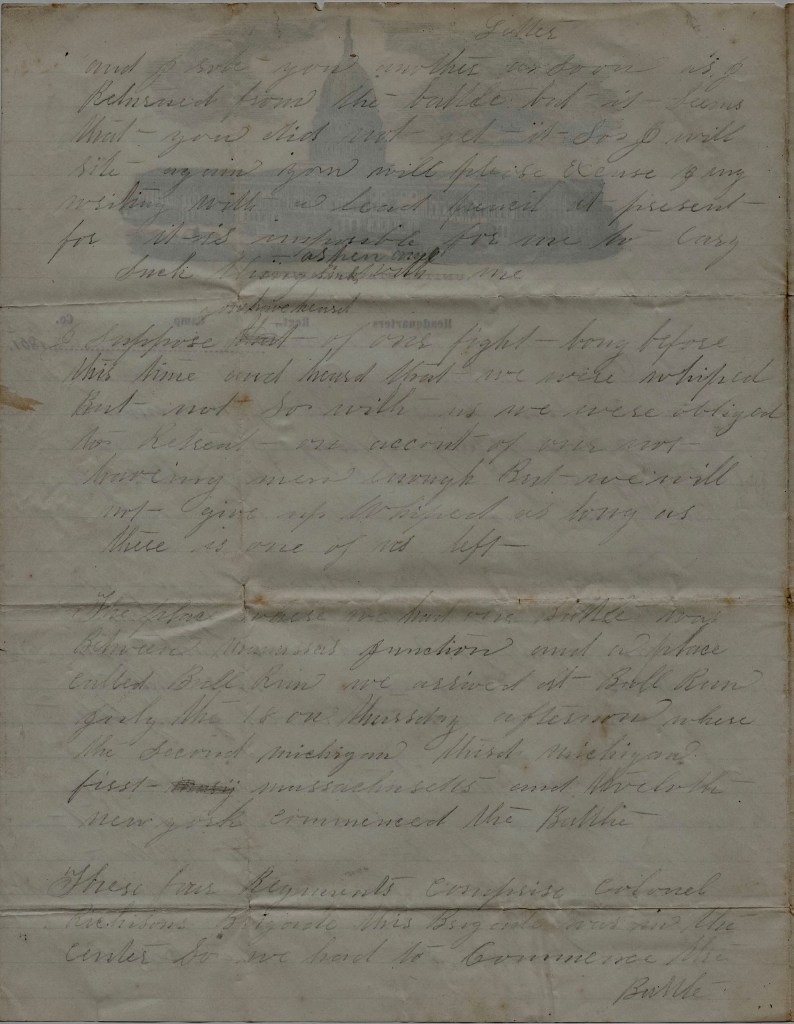

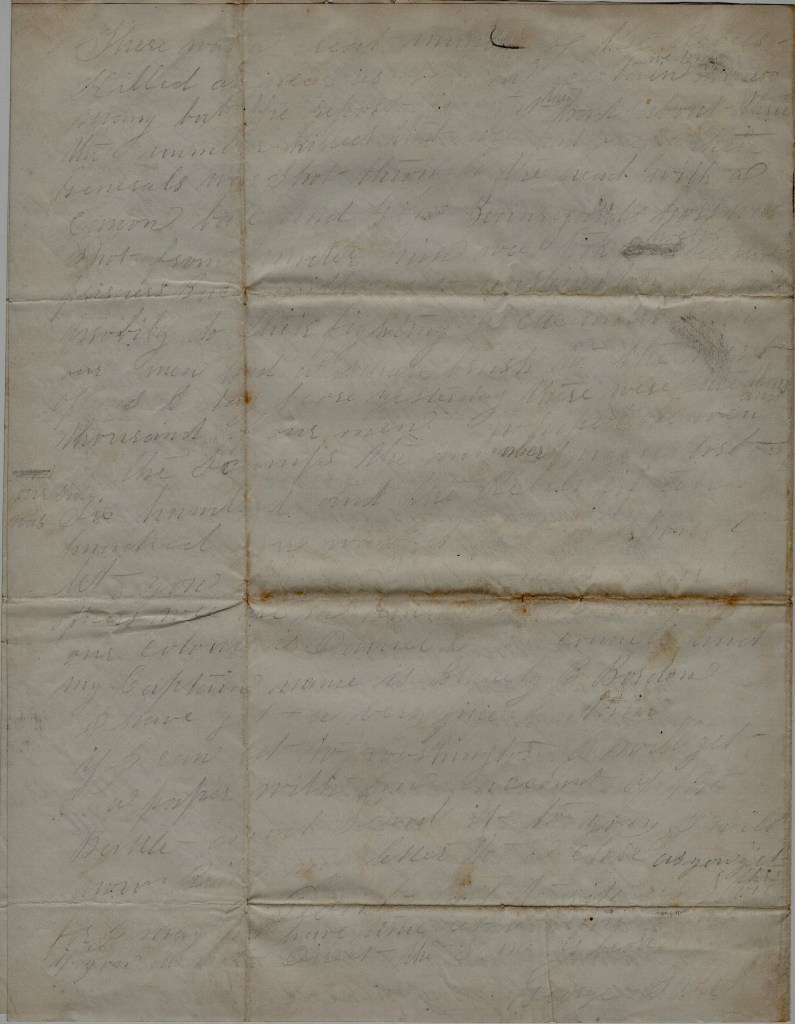

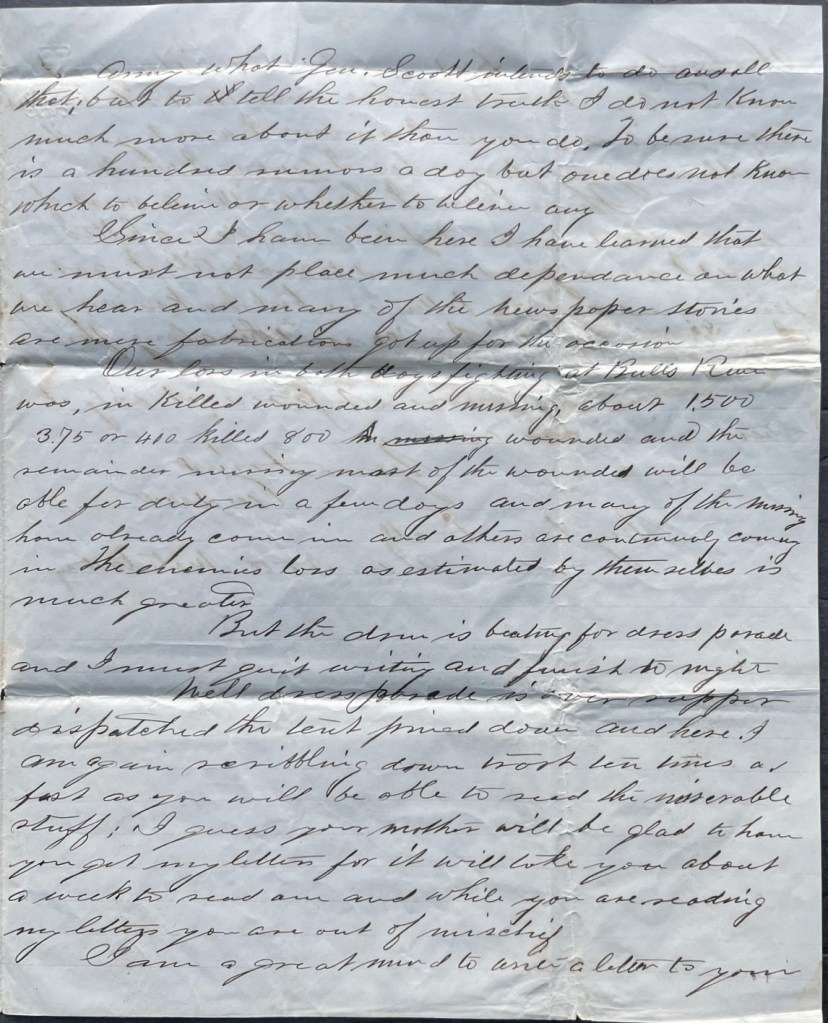

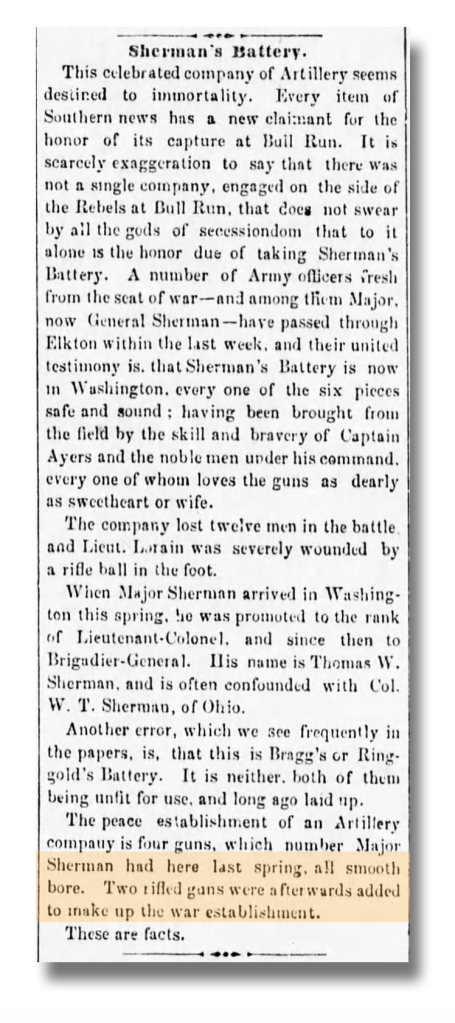

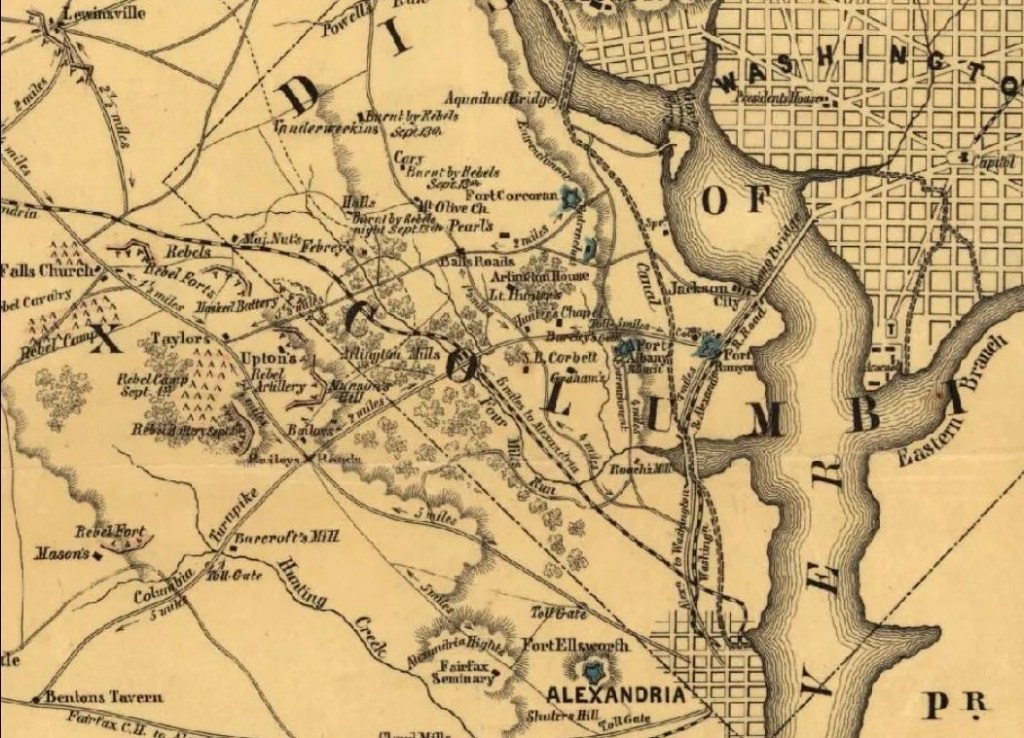

I suppose you are very anxious to hear from me & having a chance to send a letter to Washington, I will improve it & inform you of our present condition. We had a bloody battle yesterday which lasted about 4 hours commencing at 12 M. We got here & camped about 3 miles from the battle ground which is 5 miles from Manassas Junction. They had masked batteries & our troops all came right up in front of them & faced the music. There were only four thousand on our side that were in the engagement & twenty-three thousand of the rebels. There is a great loss on the rebels but to what extent, we cannot ascertain. The loss on our side numbers from twelve to twenty killed & not less than one hundred wounded. There are a great number missing that we cannot account for. They are a carrying the dead out this a.m. & burying them. Two men of our regiment were carried out & buried, sewed up in a bed tick. One of them was struck in the leg half way between the knee & thigh, shattering the bone all to pieces. The surgeons amputated it as soon as they got him to the hospital but reaction never took place. Another of our men was struck in the head by a Sharps rifle ball, killing him instantly.

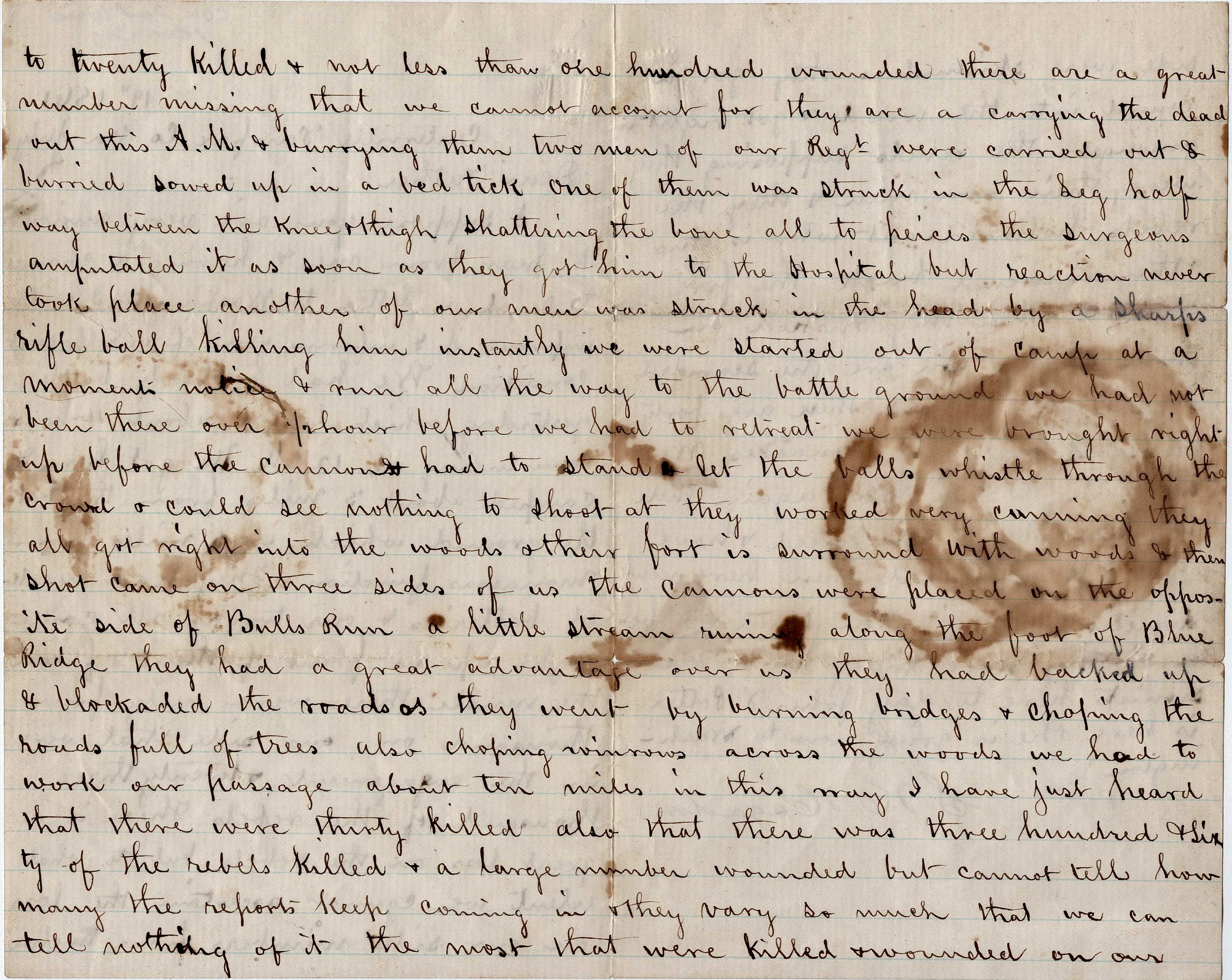

We were started out of camp at a moments notice & run all the way to the battle ground we had not been there over 1/2 hour before we had to retreat. We were brought right up before the cannons & had to stand & let the balls whistle through the crowd & could see nothing to shoot at. They were very cunning. They all got right into the woods & their fort is surrounded with woods & then shot came on three sides of us. The cannons were placed on the opposite side of Bulls Run—a little stream running along the foot of Blue Ridge. They had a great advantage over us. They had backed up & blockaded the roads as they went by, burning bridges & chopping the roads full of trees; also chopping winrows across the woods. We had to work our passage about ten miles in this way.

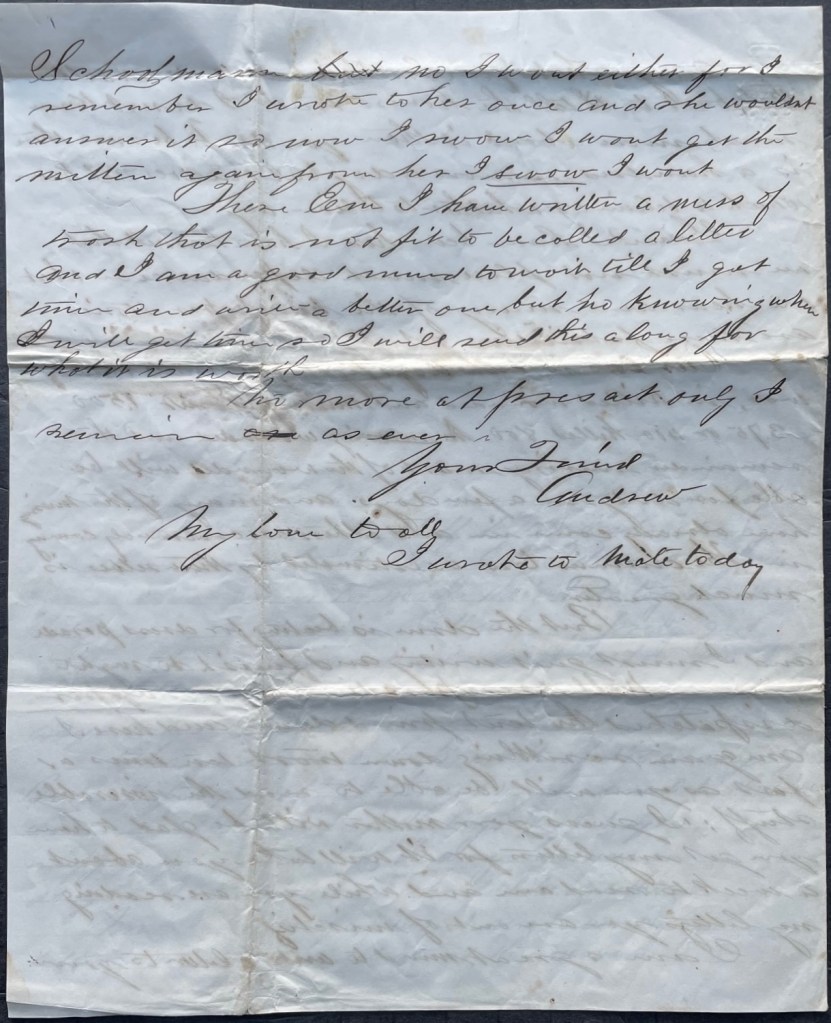

I have just heard that there were thirty killed; also that there was three hundred & sixty of the rebels killed & a large number wounded but cannot tell how many. The reports keep coming in & they vary so much that we can tell nothing of it. The most that were killed & wounded on our side were skirmishers. They got a round into the woods & got right in amongst the rebels supposing they were their own men & they—the rebels—hallowed out, “Who is this?” and they answered back, “The fire zouaves!” and then they rushed on them saying, “You are the scoundrels.” 1

I have got to close. There are forty thousand men at Manassas. We are going to try them again there. We have been reinforced & have got fifty thousand men here now. Direct to me the same as before.

They have hung three secessionists here to day. John V. Potter is here & he is going now to Washington.

— S. H. Hagadorn

1 The four regiments in Col. Richardson’s Brigade which were in the Union advance at Blackburn’s Ford included the 1st Massachusetts, the 2nd and 3rd Michigan, and the 12th New York Infantry, none of which were known as “Fire Zouaves.” It’s suspected that the reputation of the Union “Fire Zouaves” was intended to strike fear much as the Confederate “Black Horse Cavalry.” It was the 12th New York Infantry that swept through the woods on the Federal left who likely encountered the Rebels as described.