The author of this regiment remains unidentified. His surname was most certainly Williams but his initials are less certain. The content of the letter suggests it was written by a member of the 21st Virginia Infantry and after looking at soldiers in that regiment with the surname Williams, I was inclined to attribute the letter to Fields T. Williams (1821-1889), a slave holder in Buckingham County, Virginia, who enlisted in 1861. But I discovered that he was discharged for age in 1863. He also served only as a private in Co. E, 21st Virginia Infantry and the author of this letter seems to be of higher rank. Unless he returned to the service late in the war as a chaplain or in some other capacity, I doubt that this was him.

There was an Ashby Williams in the 21st Virginia and the author’s reference to “Ashby Street” in his camp suggests a connection, but I can’t make out an “A” in his initials. For the moment, our author will

The 21st Virginia marched with Ewell’s Corps and in February 1865 they were encamped southwest of Petersburg near Burgess’s Mill and the “fight” described in this letter refers to the Battle of Hatcher’s run which was fought from February 5 – 7, about six miles southwest of Petersburg, Virginia along Vaughn Road and around Hatcher’s Run.

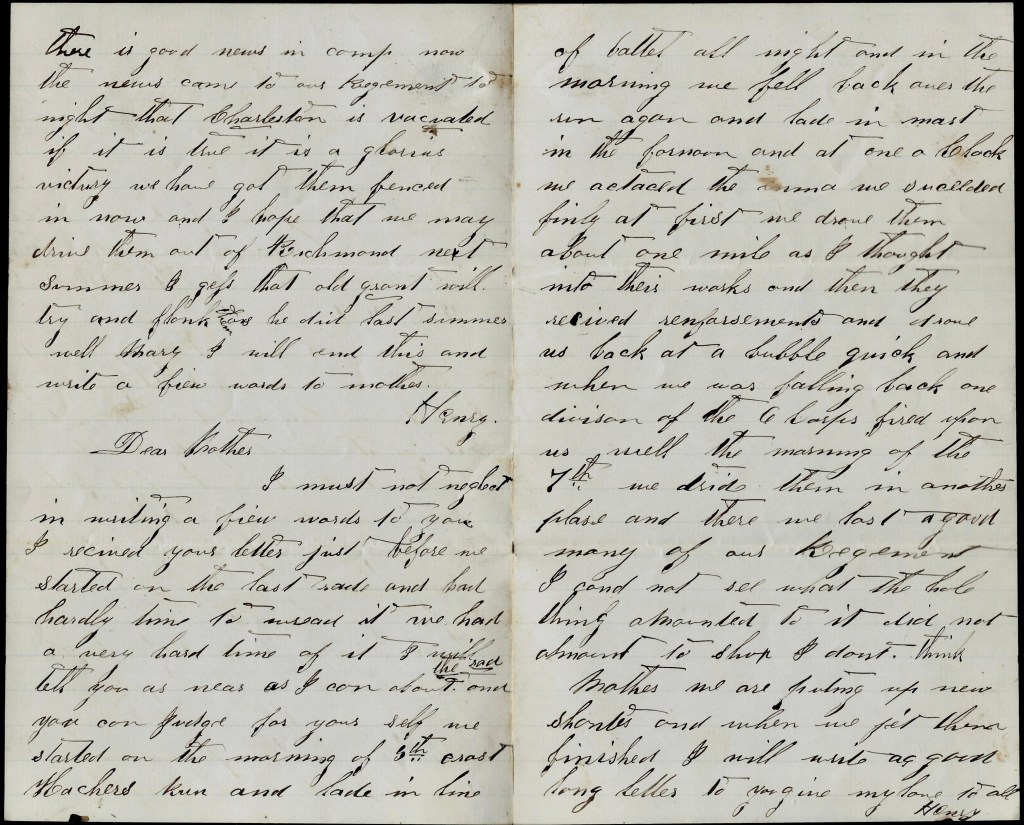

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Camp Ewell

Monday, February 6th 1865

Mu kind friend Miss Nonnie,

Yours of January 30th was received Saturday evening late. Was very glad to hear from you. Hope your illness is not serious. Guess it is only a temporary inconvenience resulting from the extreme coldness of the weather. Your presence would be an ornament to Ashby Street, I am sure, but the humble occupant of No. (13) does lay to his heart the flattering hop[e] that you will ever visit his camp except in dreams and imaginations and in these often though I suspect them involuntary. You would no doubt admire our town if you were to see it. I thought of sending you a draft of the encampment but since you have had a description of it and I am not a good artist, I have declined to do so.

As to dispatches by rumor, they are equally unreliable in a military and matrimonial connection. I am not going to be married the 22d which information obviates the necessity of an explanation of the day. Besides, you have seen ere this that the President has changed the day to March the 10th. 1 I am aware of the opinion prevailing in your vicinity in regards to Miss T and myself but it is not true. We sustain no other relation to each other than that of friendship and while we are intimate friends, I have not the first reason to suppose we will ever sustain a nearer relation than that of friendship.

So you see that although it may not be an evidence of my sympathy for soldiers, yet I will not cut one out there. I do not know what would be the difficulties that might arise in an effort to gain her as a sweetheart except her own disinclination, though it is presumable that they would be many and serious since as many are aspiring to the enviable relation—perhaps almost as numerous and dangerous as the scaly monsters of the sea who though they suffered me by dint of a manly struggle to reach the Emerald Isle of Somnambulous (thereby creating in me a strong desire to return again) have ever since baffled my most resolute efforts to revisit the charming one whose smiles welcomed and whose soft hand led me to see the lonely islands made an abode of happiness by her presence and society. If those guards of such rich a treasure are ever found asleep, I will do them as I once did the Yankee sentinals and lo! when they awake, I shall have crossed the lines. Oh hope, cheering hope, I fear you are treacherous to your old client. Suffice it to say, I am on the alert and by your permission will contend still longer.

Sunday morning a large congregation assembled at the church and how my spirits—so long depressed—were revived when I glanced at the crowd (as I am always wont to do) and thought I saw hopeful evidences of a reviving interest in religion. But alas, ere the services had fairly begun, orders came to move immediately and in a few minutes, clad in the habiliments of war, we sought the hostile fields. 2

I followed my dear old command on horseback, rode along the lines, and came to my inexpressable regret that my fears expressed to you were too well grounded. Our men fired one round and many of them ingloriously fled without so much as seeing the enemy. Several of my regiment were wounded and I am deeply grieved to tell you one of my best friends and most zealous co-laborers in Christ was mortally wounded—Lieutenant [J C.] Kyle. He fell shot in the head. Has not spoken since. His immortal part seems only to be detained for a short time. He used to raise tunes for me (I am a poor singer). He will never sing for us again. Doubtless his next song will be sounded on the heavenly orchestra. How sad a loss to us. But oh! how much worse the pain to his family. Only yesterday morning I noticed him in his place in the Chapel looking unusually well and cheerful, and before the close of the day he lay senseless and bleeding on the ground.

Our life is like the summer rose

Which opens to the morning sky

And ere the shades of evening close

Are scattered on the ground to die. 3

I feel sad when I think nearly all my intimate personal friends have been killed or captured. But he I hope was prepared. I could not call him back since it is the Father’s will he should go. Let no rude hand distrust the willow that must soon wave over his tomb. Let true hearts and tears preserve and [ ] memory, and let those who would be wise be also prepared.

After returning late yesterday evening, I went to the depot to meet Mr. Whitehead and brought the box into camp last night. I know no epression adequate to signify my gratitude. It cheers me. It makes me feel I am not forgotten though a long way from home. I have seen others receiving boxes and wished my relatives could send me a box, not for the luxuries they contain (which is no small item either) but the affections which arise therefrom. Now I have one—the first I ever received—and I am so proud of it. I thank you for so tangible a proof of your friendship.

My command has gone out again on the line of battle. I hear them fighting now. I must go to them as soon as is practicable. I feel a deep concern. I will give your box which I prize so much to the poor men who are now in the fight and will no doubt get wounded. I know you are willing I should give a part to the wounded. They are as dear as brothers after they are wounded, no matter how they act when well. I am excited and must close. The fight is just commencing. Only a few moments ago we heard the first gun. If any evil befalls any of your neighbors, I will try promptly as possible to inform you.

Yours truly, — F. T. [?] Williams

1 The Confederate Congress invited President Jeff Davis to “appoint a day of public fasting, humiliation and prayer,” Davis chose Friday, March 10, 1865.

2 Correspondence from the 21st Virginia published in the Richmond Dispatch reported that “Until yesterday [Feb. 5, 1865], everything has been, for some time, as quiet as could be desired along these lines. The soldiers are enjoying, with great relish, the presents sent them by their friends. Numbers of boxes are each day arriving, and the men are, comparatively, well satisfied, and the war spirit daily increasing. Yesterday morning, however, just as we had assembled, for the first time, in our chapel for worship, and the second prayer had been concluded,–just as the minister was about to announce his text,–orders were received to move at once. This was announced from the pulpit, with the request that all would remain until the benediction should be pronounced. It was a great scene, and one impressive to every man. The blessing of God was invoked upon each and every one present, and we started out on an expedition, from which some will never return.”

3 These lines are from a poem by Richard Henry Wilde. He died in New Orleans of yellow fever in 1847.