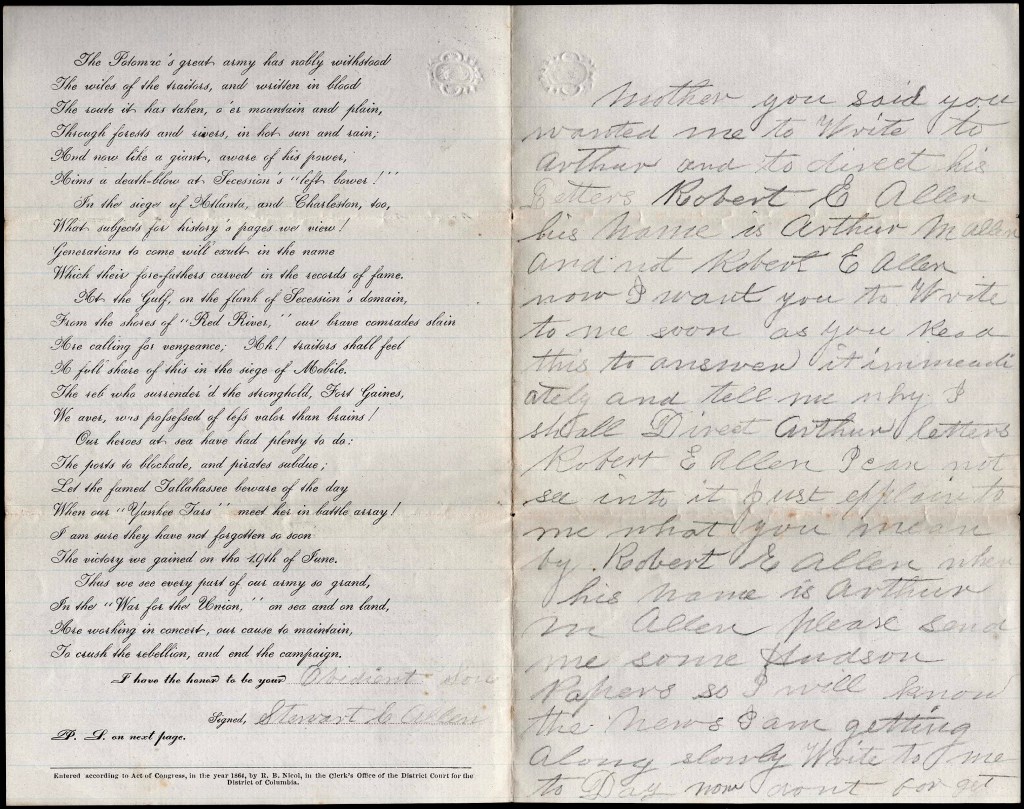

The following letter was written on most unusual stationery by Stewart C. Allen (1843-1918), the son of Edward Allen (1799-1848) and Harriet Ann Foland (1811-1885) of Hudson, Columbia county, New York.

Stewart enlisted on 14 February 1862 as a private in Co. B, 93rd New York Infantry. He received a severe wound in the right shoulder during the Battle of Spottsylvania Court House on 10 May 1864 and wrote this letter while recuperating from that wound at Campbell General Hospital in Washington D. C.

The letter was a pre-formatted letter, written in prose, enabling the soldier to merely fill in a few blanks and then add a personal note as a post script. Stewart’s post script begs his mother to explain why he should address letters to his younger brother (Arthur M. Allen, b. 1845) by some name other than his given name. Apparently he was operating under an alias for some reason.

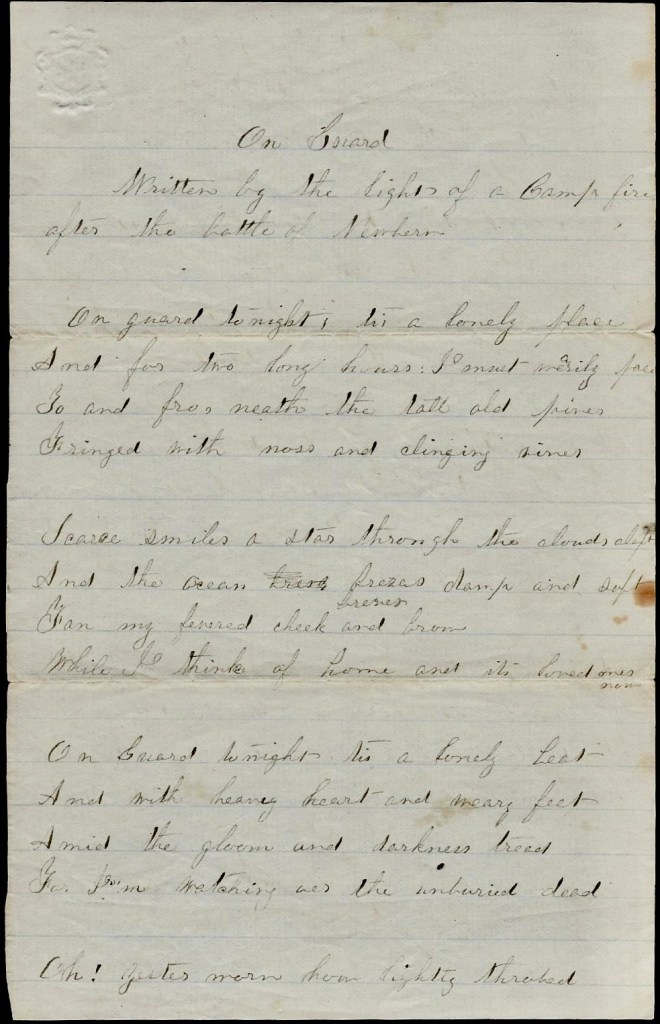

I have searched for the poem on the internet and could not find it published so have transcribed it in entirety.

As a matter of curiosity, Stewart did not marry until 1899 when he was 46 years old. He married 22 year-old Edith Carter and she lived on her husband’s war pension until her death in 1968.

[Note: The bold lettered font is what Stewart wrote; the italicized font was pre-printed.]

Transcription

Campbell Hospital

Ward Nine

October 30th 1864

Dear Mother and Sister,

As writing materials often are scarce,

I purpose to write you a letter in verse;

To condense my ideas, save paper and time,

Is my object for writing the letter in rhyme.

Of course you will now it is one of my pranks!

It will take but a minute to fill up the blanks.

I received your kind letter just one day ago,

Which found me a member of “Uncle Sam’s Show,”

And for two months or better, expect to remain,

Unless like full many, I chance to be slain;

Should this be my fate, the last boon I crave

Is to mark on my tomb-stone, “A Patriot’s Grave!”

In the hist’ry of wars, as we carefully scan,

Since the first one was waged by man against man,

In all the fierce conflicts no records remain

Which will be compared to the present campaign.

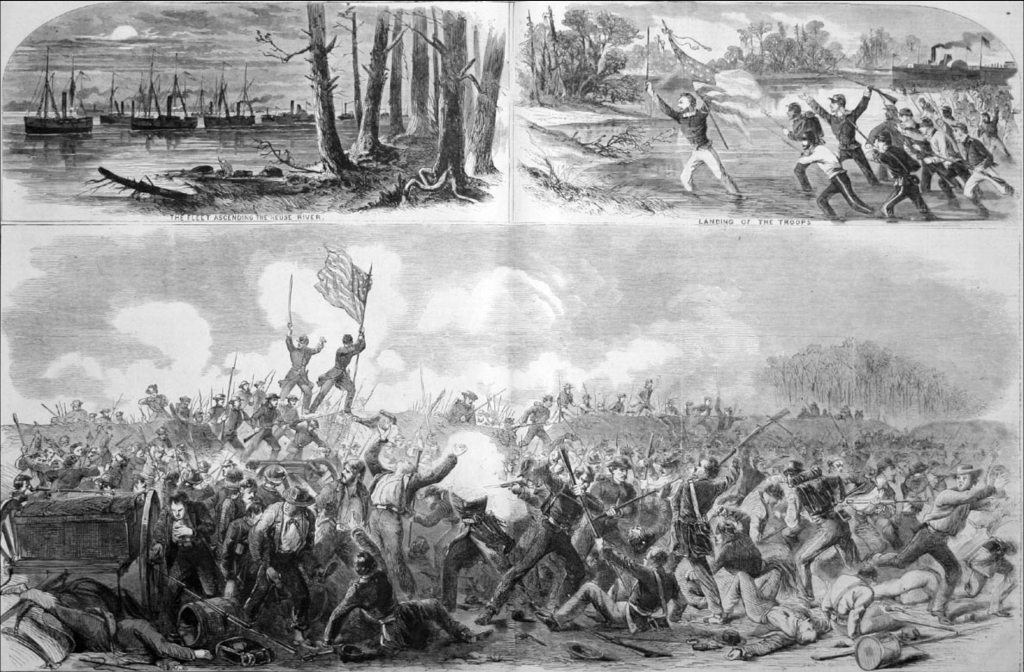

The war has been general, on both land and sea,

And many have fallen for “Liberty’s Tree!”

It would fill many volumes to pass in review

What our various armies this year have been through,

Though my space is not large, yet ’twill not be amiss

To give a slight sketch on a small sheet like this.

The Potomac’s great army has nobly with stood

The wile’s of the traitors, and written in blood

The route it has taken, o’er mountain and plain,

Through forests and rivers, in hot sun and rain;

And now like a giant, aware of his power,

Aims a death-blow at Secession’s “left bower!”

In the siege of Atlanta and Charleston too,

What subjects for history’s pages we view!

Generations to come will exult in the name

of which their fore-fathers carved in the records of fame.

At the Gulf, on the flank of Secession’s domain,

From the shores of “Red River” our brave comrades slain

Are calling for vengeance; Ah! traitors shall feel

A full share of this in the siege of Mobile.

The reb who surrender’d the stronghold Fort Gaines,

We aver, was possessed of less valor than brains!

Our heroes at sea have had plenty to do:

The ports to blockade, and pirates subdue;

Let the famed Tallahassee beware of the day

When our “Yankee Tars” meet her in battle array!

I am sure they have not forgotten so soon,

the victory we gained on the 10th of June.

Thus we see every part of our army so grand,

In the “War for the Union,” on sea and on land,

Are working in concert, our cause to maintain,

To crush the rebellion, and end the campaign.

I have the honor to be your obedient son. Signed, Stewart C. Allen

P. S. on next page.

Mother, you said you wanted me to write to Arthur and to direct his letters Robert E. Allen. His name is Arthur M. Allen and not Robert E. Allen. Now I want you to write to me soon as you read this to answer it immediately and tell me why I shall direct Arthur letters, “Robert E. Allen.” I cannot see into it. Just explain to me what you mean by Robert E. Allen when his name is Arthur M. Allen. Please send me some Hudson papers so I will know the news. I am getting along slowly. Write to me today. Now don’t forget.