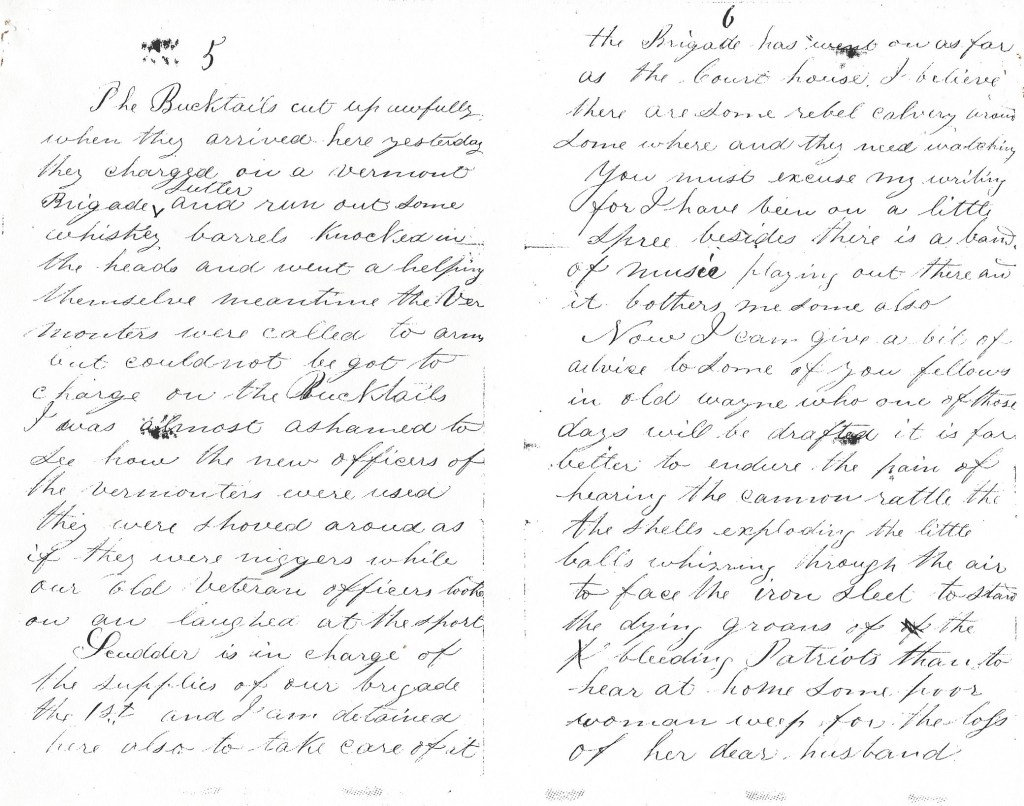

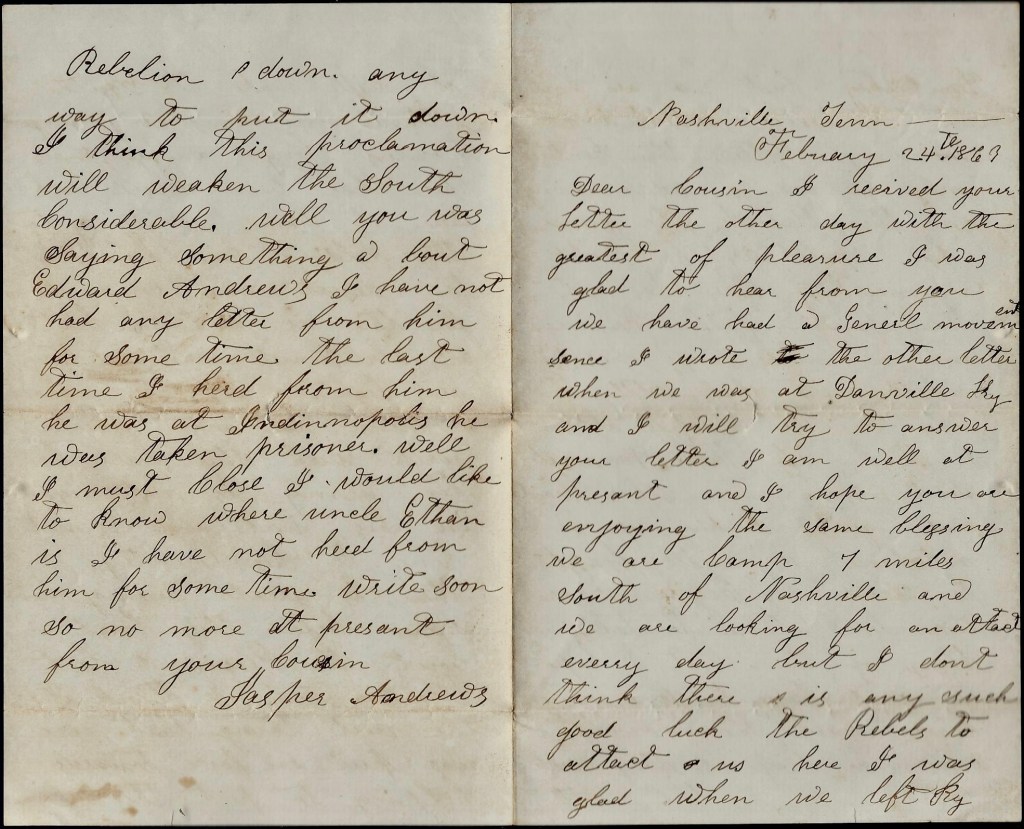

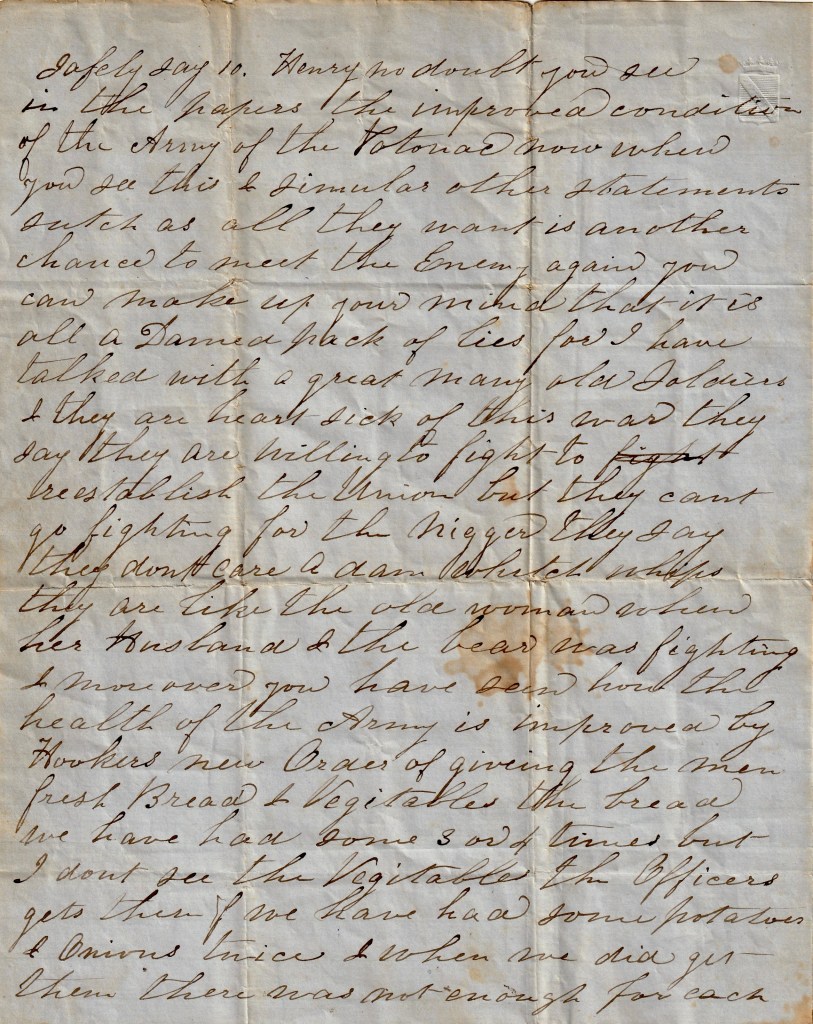

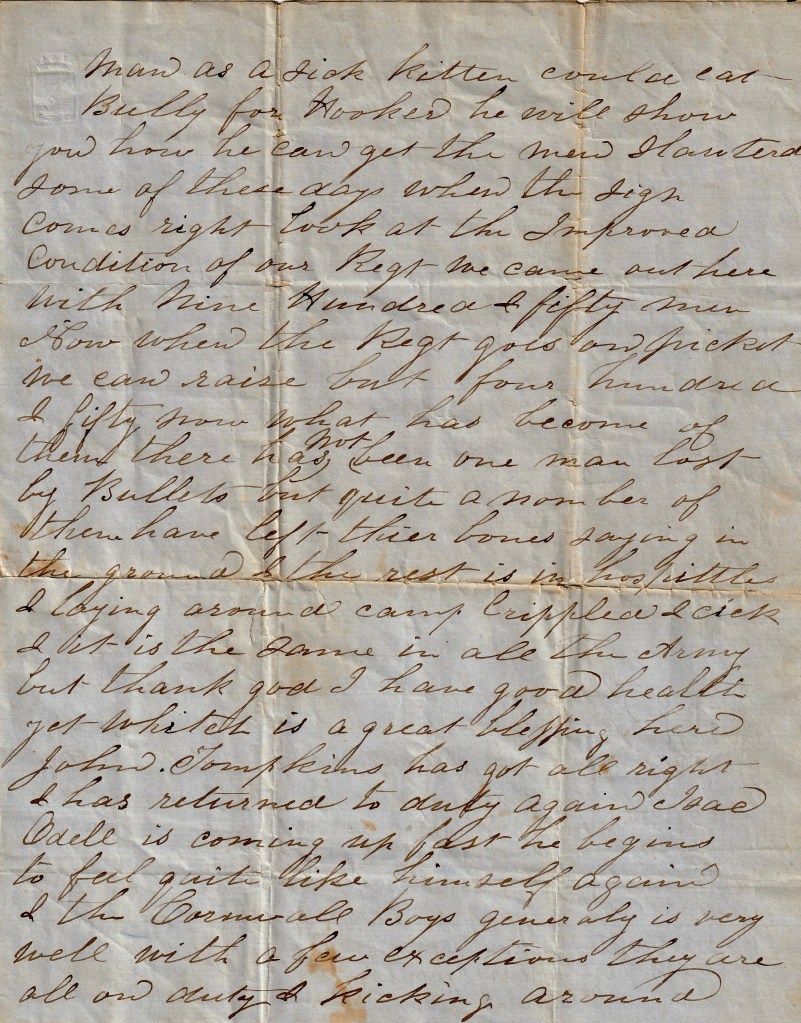

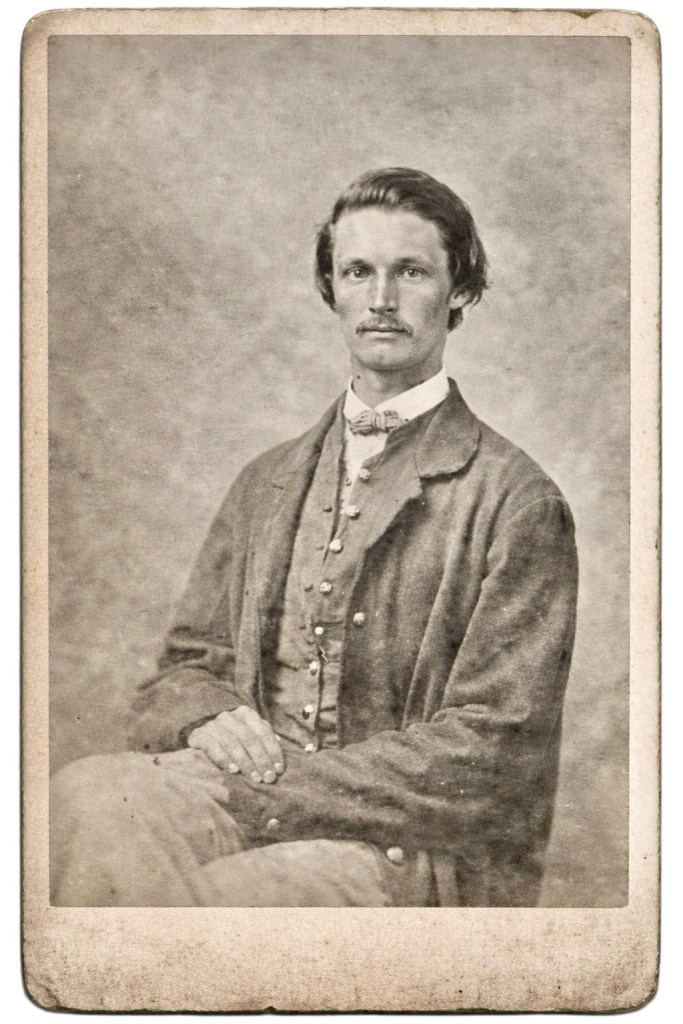

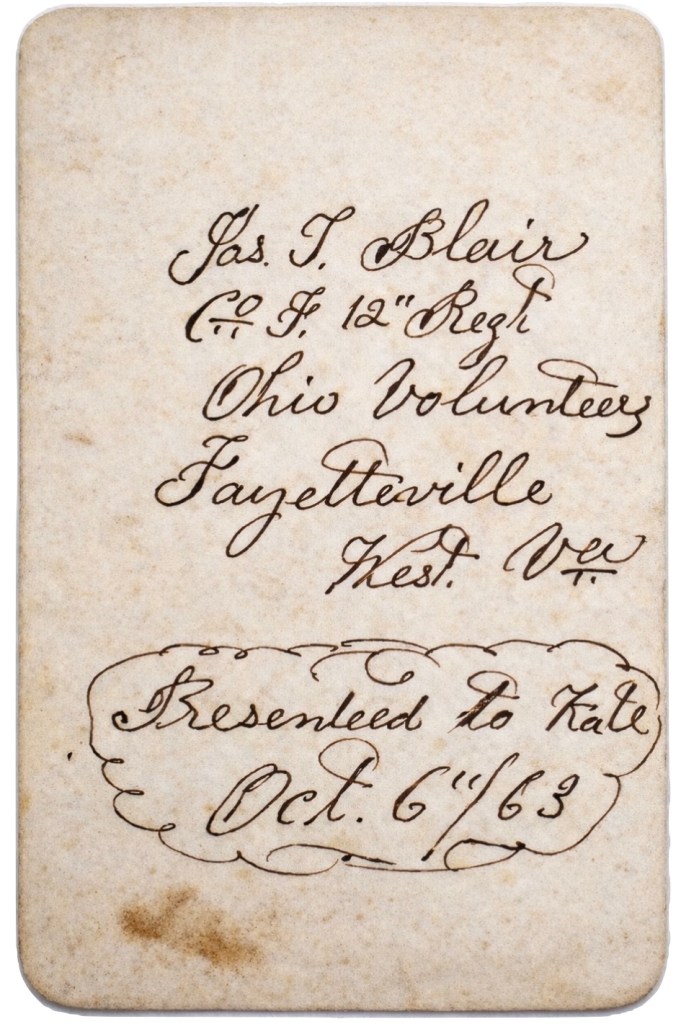

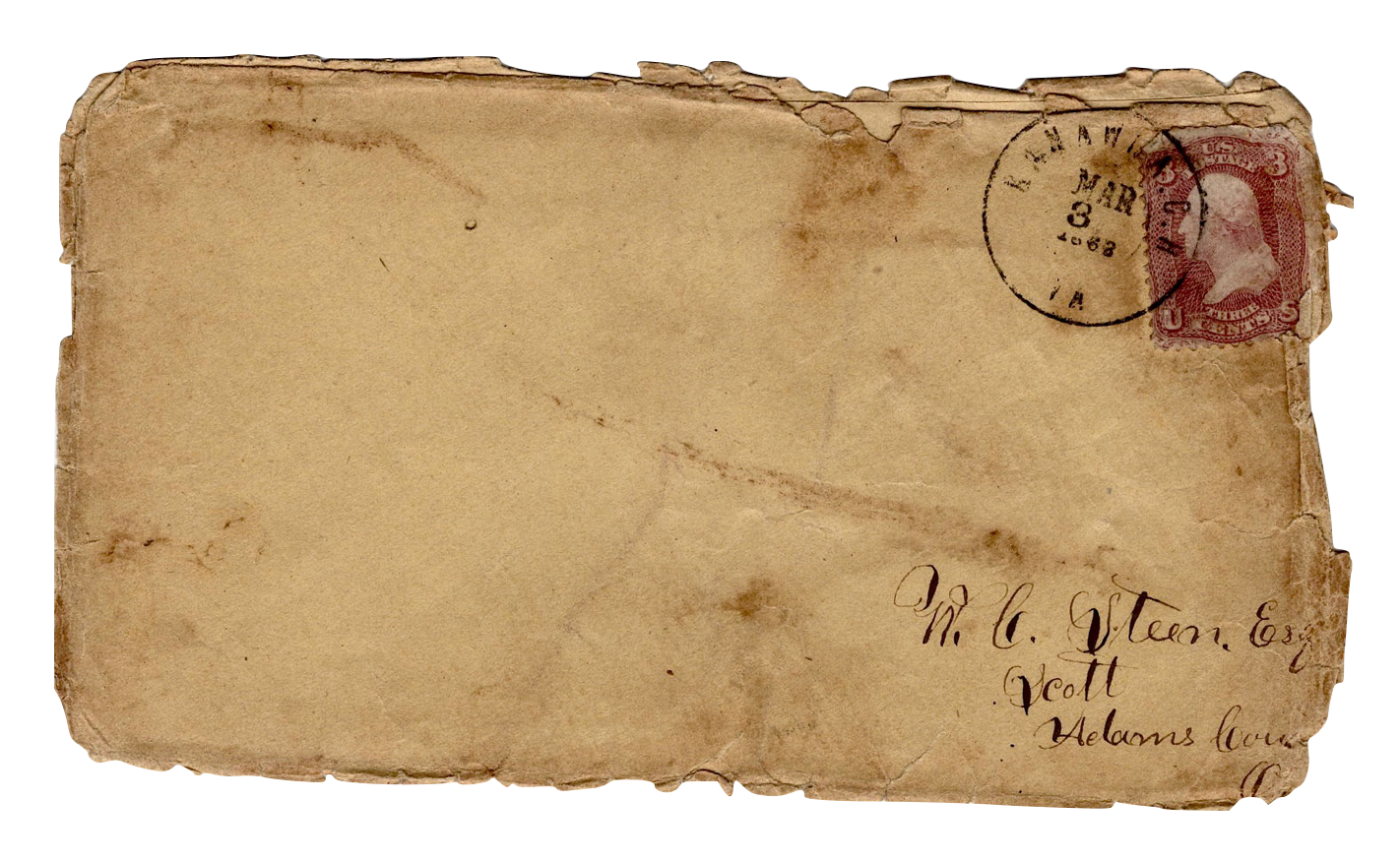

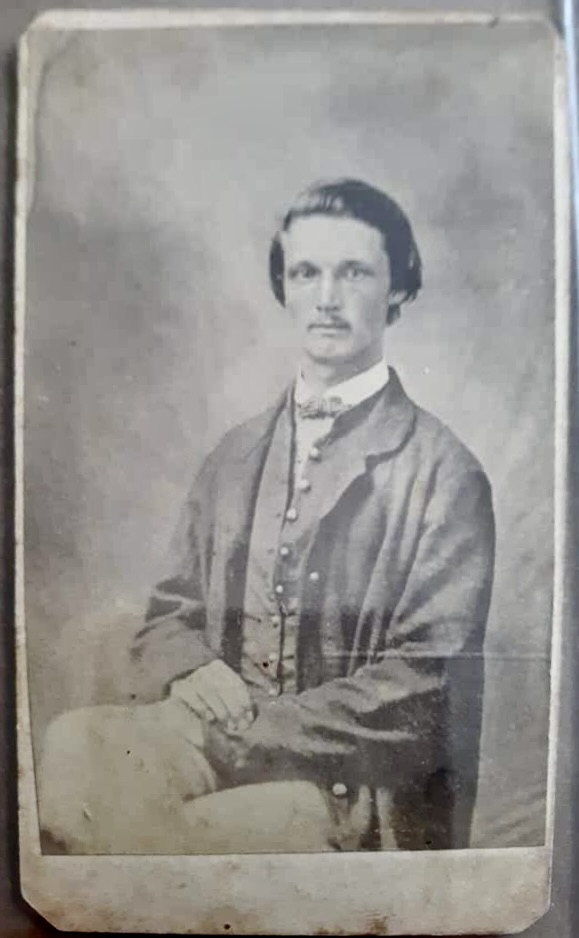

These letters were written by 19 year-old Joseph T. Blair (1843-1863) of Co. F, 12th Ohio Regiment. Joseph was the son of Samuel Blair (1820-1844) and Eliza Ann McClure (1819-1890) of Adams county, Ohio.

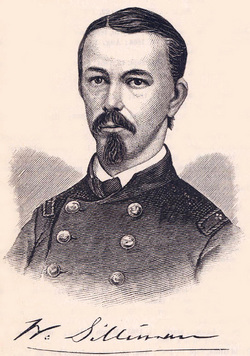

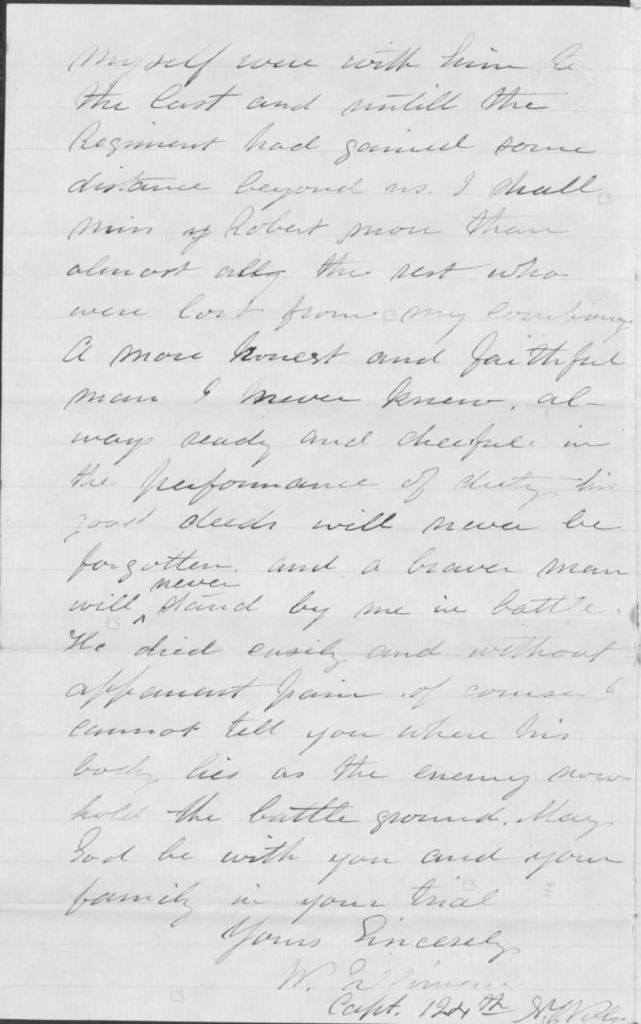

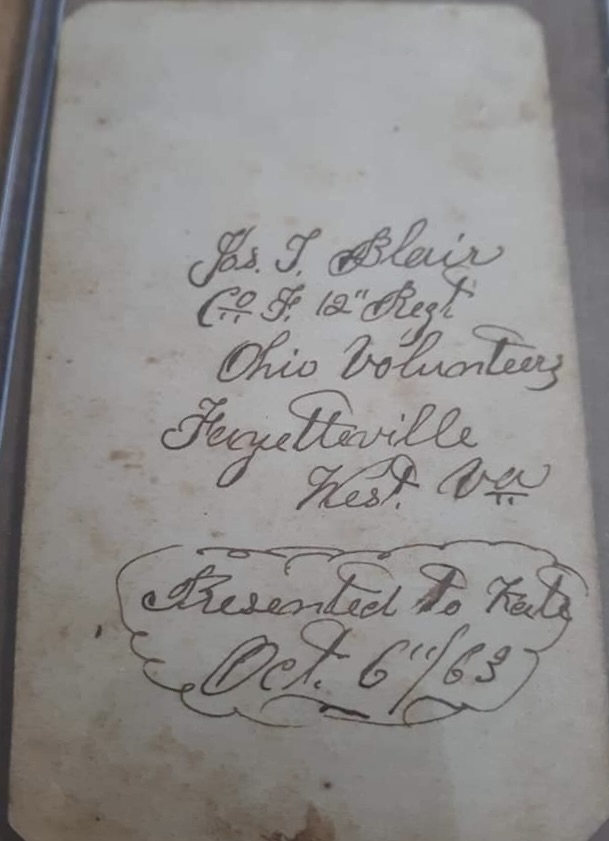

Joseph died on 10 November 1863 as a result of a gunshot wound received at the hands of guerrillas while scouting near Boyers Ferry on 31 October 1863. The CdV above picturing Joseph T. Blair was found on Facebook. The inscription in James’ own handwriting on the reverse of the card was written just a month before he was killed by guerrillas. The images were AI generated to sharpen them. The original images appear at the end of these letters.

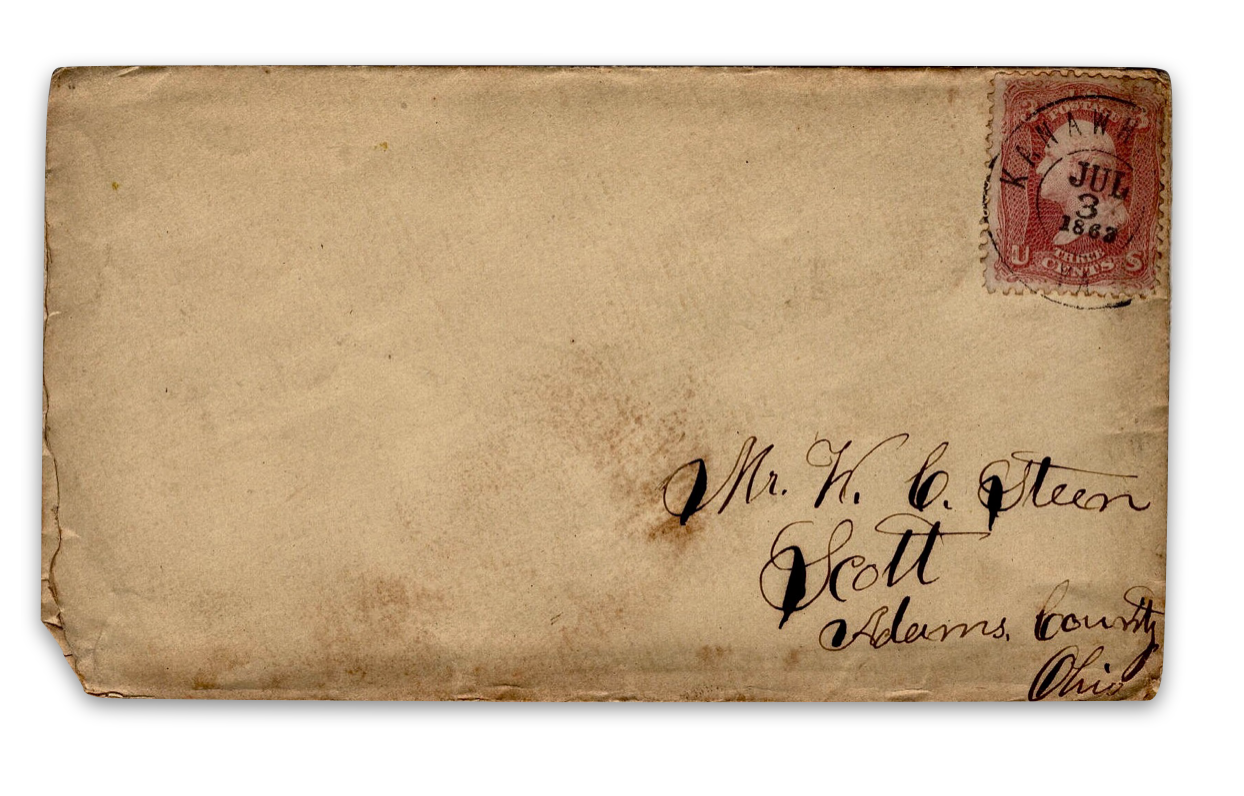

Joseph wrote these letters to his cousins, John Alexander Steen (1841-1918) and William “Chester” Steen (1845-1927). They were two of the sons of Alexander Boyd Steen (1813-1896) and Nancy Jane McClure (1821-1893) of Winchester, Adams county, Ohio.

Letter 1

Camp Warren near Charleston, Virginia

March the 21st 1862

Mr. John & Chester Steen

My dear cousins,

I with pleasure resume my pen to inform you that your letter of the 10th inst. came to hand today and read it with much pleasure, and as it was raining today and all nature looks sad and melancholy, I seat myself to spend a pleasant hour in replying to you. I was glad to hear of you being in good health. My health is quite good at present.

Well, I believe that the best news that I have to write to you at this time is that the weather has been very good for about two weeks until today and it is again raining, but not such disagreeably rain as we formerly had. Spring seems to be open already. We have indications of its approach in the warm and balmy air and the warbling notes of the birds are heard in the forest. Old winter’s icy reign is yielding to the gentler sway of spring which we welcome with grateful hearts. I trust the spring will open with auspicious promises and its labors be largely remunerative to you, my agricultural friends, so that you may rejoice in its abundant and golden fruits, and ‘ere spring ends, I hope to see this wicked Rebellion crushed and peace and prosperity again reign over our once prosperous and happy country.

You spoke of having quit your school and again went to work. Well I guess the time is near at hand when I will have to work. Probably I shall not be occupied in the same kind of work which you are, but I assure you that it will not be much easier. You will be engaged on a farm and I will be engaged on the Mountains hunting for seceshers. There is evidently a movement on hand up the valley. Yesterday the 34th Ohio Regiment passed by here bound for Gauley Bridge and I understand that the 60th Regiment is on its way up here. Our Artillery company left us some time ago and I think that we shall follow them before long. I suppose that our destination will be to cross the mountains and take possession of Lewisburg and the Tennessee Railroad and in so doing, we will cooperate with our troops at Manassas. Such is my idea of these movements but I cannot ascertain anything certain for you know that military leaders always keep a provoking silence on all such things. I had hoped to get out of Virginia when we again marched, but I guess that I am bound to disappointment for at present there is strong indications of having to take a March across the mountains.

The principal topics which are discussed in camp is in regard to Frémont being appointed Major General of the Department of the Mountains, and you are well aware that our regiment belongs to that department. I don’t know but what he is a very good man, but I know that he is not very popular in the Old 12th. Our boys all think that he is an abolitionist and our regiment has a great dislike to that party. However, I should like to see the old gent who has caused so much trouble in the War Department. I would advise him to keep his abolition sentiment to himself when he is with the 12th Regiment, else it might prove to be unwholesome for him. We look for him here shortly to review us. His headquarters is at Wheeling, Va.

You spoke in your letter of the death of Spencer Wilson. ¹ It was a very sad occurrence. I think that it must have grieved his father a great deal. I have seen many such cases — only worse. Many a poor fellow have I seen buried out in the mountains without a coffin or a friend nigh him. There has been three deaths in our regiment within the last week. Their deaths was caused by exposure. One of the boys which belongs to my company has just returned this evening from Ohio where he has been home sick. He brought us all the news from the vicinity of Lebanon. He says that the folks about there thinks that the war is about over. How is it in your neighborhood? Do you think that it will be over anyways soon? We all think that it will terminate this spring. We get a telegraph dispatch every morning and it always contains good news. The Rebels seem to get repulsed on all occasions. The dispatch this morning announced the capture of Newbern, North Carolina, by Gen. Burnside. It also stated that the fight was still going on at Island No. 10. They have been fighting there for three or four days. I suppose that is something similar to the fight we had last November at Gauley Bridge. We cannonaded there for over a week and there was apparently but little damage done on either side. But I think that the rebels is about whipped out. We have driven them out of all their strongholds — namely Columbus, Bowling Green, and Manassas. If they are not well enough fortified at those places to stand and fight us, I don’t think that they will find a place on the whole continent where they can.

I see that their press has quit blowing that one Southern man can whip five Northern men. I think it about time for their brave sons of the South has had their fighting qualities pretty well tested of late, and I guess that they find a Northern man — or Yankee as they call them — is just as good as any of their Southern chivalry, and proves to stand fire a little longer if any difference. I am not certain but my impression is that the Old 12th will have to try her nerve again before the war is over.

Well, I am no ways anxious for a fight but if fight we must, I believe that the 12th Regiment will stand fire about as long as any of them. We never was whipped but once and I don’t think it likely that we will get whipped again, but I won’t say that we can whip five Rebel Regiments. That would sound too much like the Southern gas.

We have got an Old Secesh in jail here now who killed one of our spies last summer. His own son is here to testify against him. He has not had his trial yet. I don’t [know] what they will do with him but I think that very likely he will look through a halter. There is a Negro to be hung in Charleston next week for killing his master. I did not learn the particulars of the case.

I am on picket guard tomorrow. We have to go on about every three days. We have fun when we are out on picket telling the Secesh ladies as they pass by about the Union victories. It makes them hang their heads and look like they could not help it and I don’t believe that they can help it either although if talking and sour looks would do any good, they might. You said that a woman bit you once, John, but it did not hurt. I will bet if you would see one of these sour looking Secesh women, you would say that you would rather be bit by a rattle snake than to have her to bite you. You spoke of going to see your woman again. You must certainly be going to get married before long. You had better wait until the war is over so that I can attend your wedding and besides that you will have plenty of company for I know of lots of folks that are a going to get married after the war is over. I expect that I will stay in Virginia and marry a Secesher. I have almost fell in love with some of the sweet creatures.

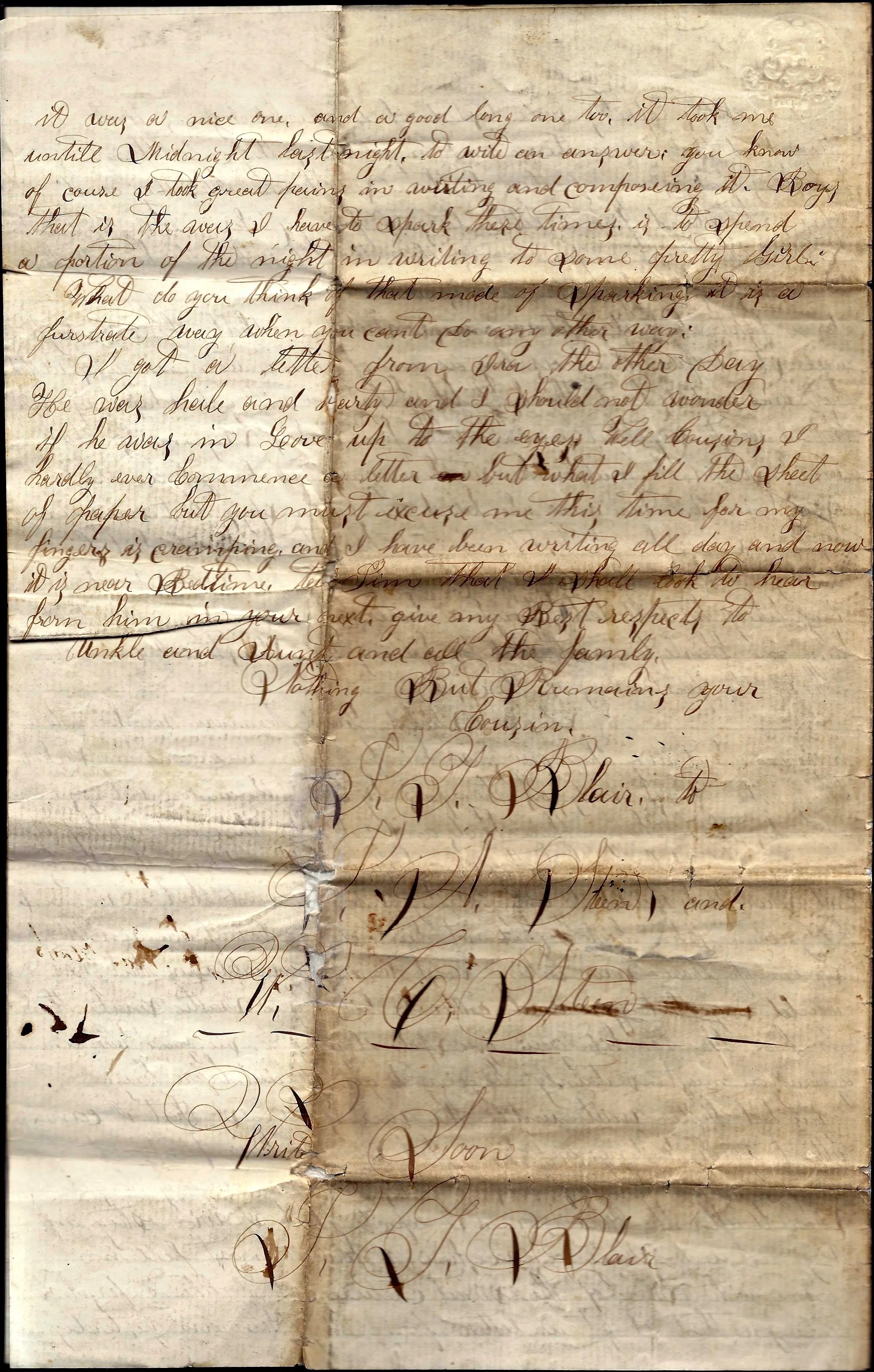

Oh, I like to forgot to tell you that I got a letter from a woman yesterday. It was a nice one and a good long one too. It took me until midnight last night to write an answer. You know of course I took great pains in writing and composing it. Boys, that is the war. I have to spark these times __ to spend a portion of the night in writing to some pretty girl. What do you think of that mode of sparking? It is a first rate way when you can’t do any other way.

I got a letter from Ira the other day. He was hale and hearty and I should not wonder if he was in love up to the eyes. Well, cousins, I hardly ever commence a letter but what I fill the sheet of paper but you must excuse me this time for my fingers is crimping and I have been writing all day and now it is near bedtime. Tell Jim that I shall look to hear from him in your next. Give my best respects to Uncle and Aunt and all the family.

Nothing, but remain your cousin, — J. T. Blair

to J. A. Steen and W. C. Steen

Write soon.

¹ 1st Sgt. Spencer Wilson was the 19 year-old son of Congressman John Thomas Wilson of Adams county, Ohio. He served with the 33rd Ohio Infantry until his death at Louisville on 4 March 1862.

Letter 2

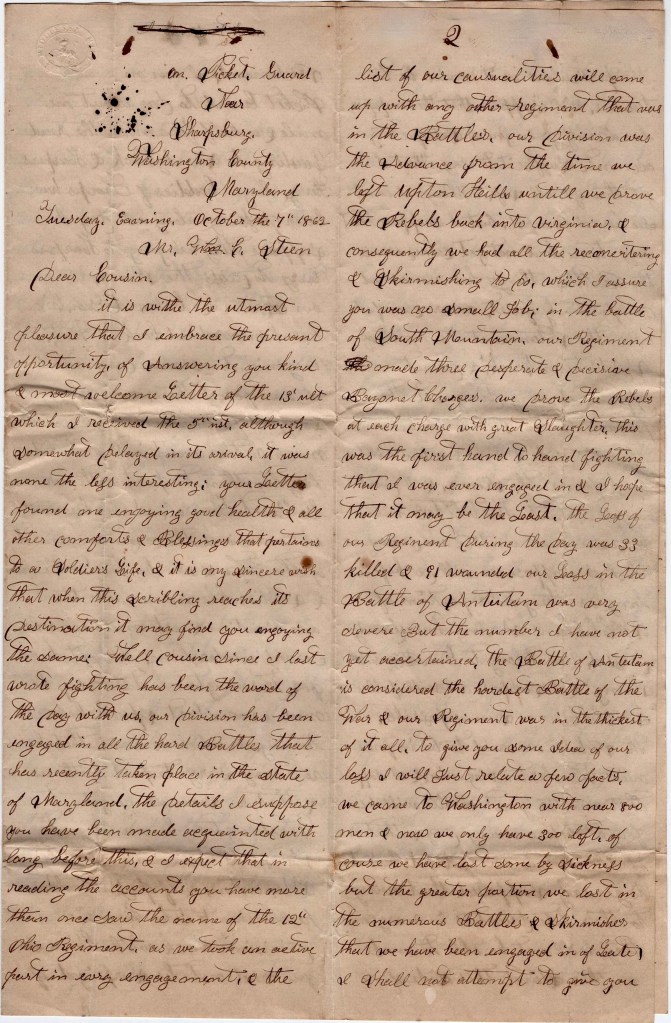

On Picket Guard near Sharpsburg, Washington county, Maryland

Tuesday evening, October the 7th 1862

Mr. Wm. C. Steen, dear cousin,

It is with the utmost pleasure that I embrace the present opportunity of answering your kind and most welcome letter of the 13th ult. which I received the 5th inst. Although somewhat delated in its arrival, it was nonetheless interesting. Your letter found me enjoying good health & all other comforts & blessings that pertains to a Soldier’s Life, and it is my sincere wish when this scribbling reaches its destination, it may find you enjoying the same.

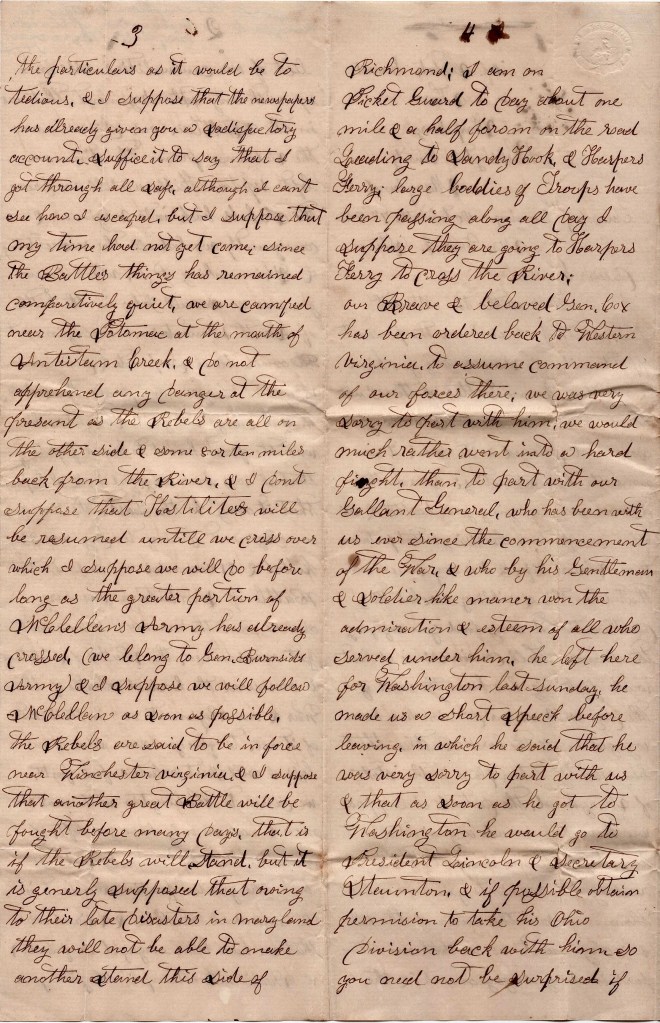

Well cousin, since I last wrote, fighting has been the word of the day with us. Our Division has been engaged in all the hard battles that has recently taken place in the State of Maryland, the details I suppose you have been made acquainted with long before this. And I expect that in reading the accountsm you have more than once saw the name of the 12th Ohio Regiment as we took an active part in every engagement and the list of casualties will come up with any other regiment that was in the battles.

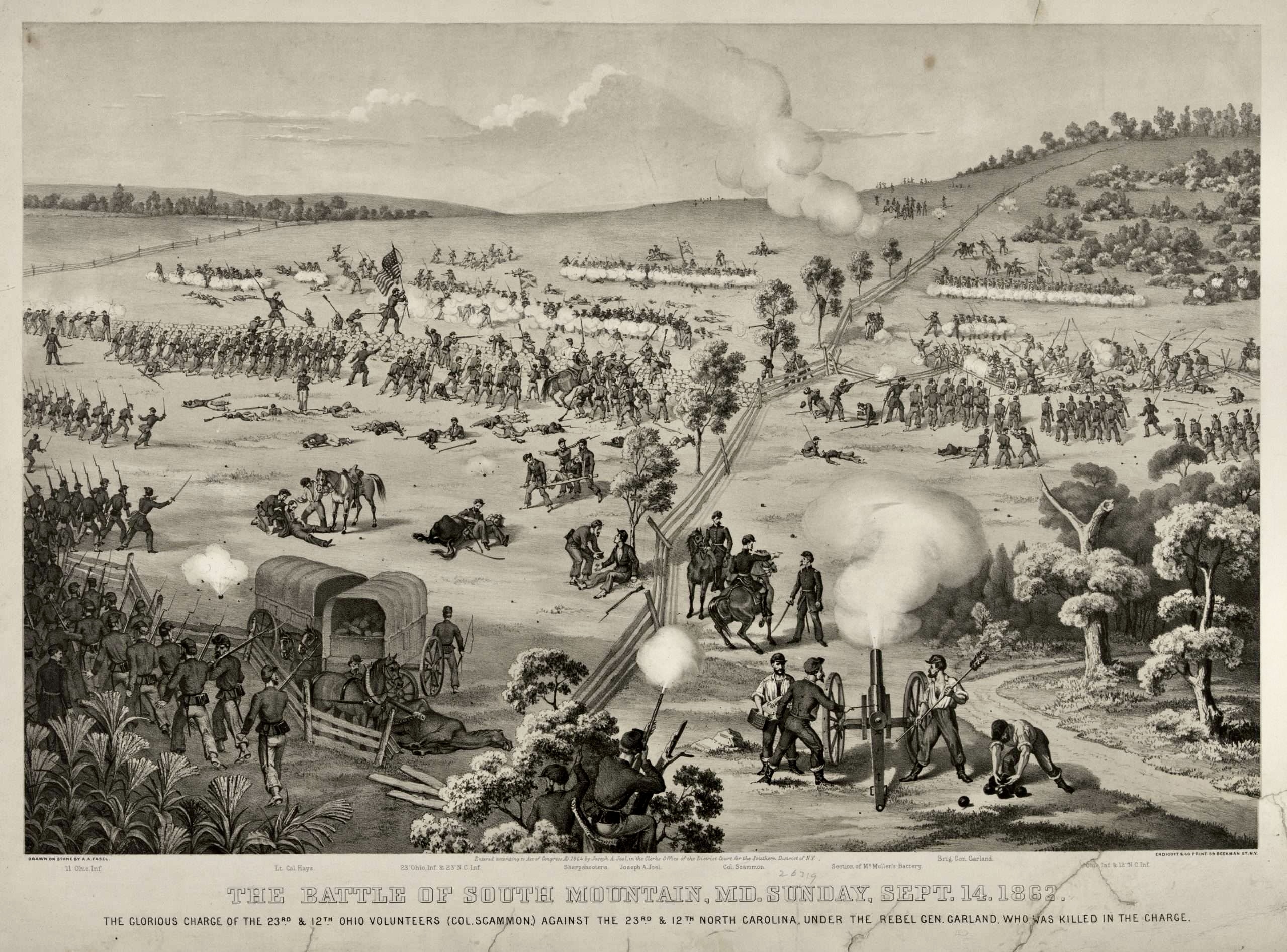

Our Division was [in] the advance from the time we left Upton Hills until we drove the Rebels back into Virginia & consequently we had all the reconnoitering & skirmishing to do which, I assure you, was no small job. In the Battle of South Mountain, our regiment made three desperate and decisive bayonet charges. We drove the Rebels at each charge with great slaughter. This was the first hand to hand fighting that I ever was engaged in & I hope that it may be the last. The loss of our regiment during the day was 33 killed & 91 wounded. 1

Our loss in the Battle of Antietam was very severe but the number I have not yet ascertained. The Battle of Antietam is considered the hardest battle of the war & our regiment was in the thickest of it all. To give you some idea of our loss, I will just relate a few facts. We came to Washington with near 800 men & now we only have 300 left. Of course we have lost some by sickness but the greater portion we lost in the numerous battles & skirmishes that we have been engaged in of late. I shall not attempt to give you the particulars as it would be too tedious, & I suppose that the newspapers have already given you a satisfactory account. Suffice it to say that I got through all safe although I can’t see how I escaped. But I suppose that my time had not yet come. 2

Since the battles, things has remained comparatively quiet. We are camped near the Potomac at the mouth of Antietam Creek & do not apprehend any danger at the present as the Rebels are all on the other side & some 8 or q0 miles back from the river. And I don’t suppose that hostilities will be resumed until we cross over which I suppose we will do before long as the greater portion of McClellan’s Army has already crossed (we belong to Gen. Burnside’s Army) & I suppose we will follow McClellan as soon as possible. The Rebels are said to be in force near Winchester, Virginia, & I suppose that another great battle will be fought before many days—that is, if the Rebels will stand. But it is generally supposed that owing to their late disasters in Maryland, they will not be able to make another stand tis side of Richmond.

I am on Picket Guard today about one mile and a half from on the road leading to Sandy Hook & Harpers Ferry. Large bodies of troops have been passing along all day. I suppose they are going to Harpers Ferry to cross the river.

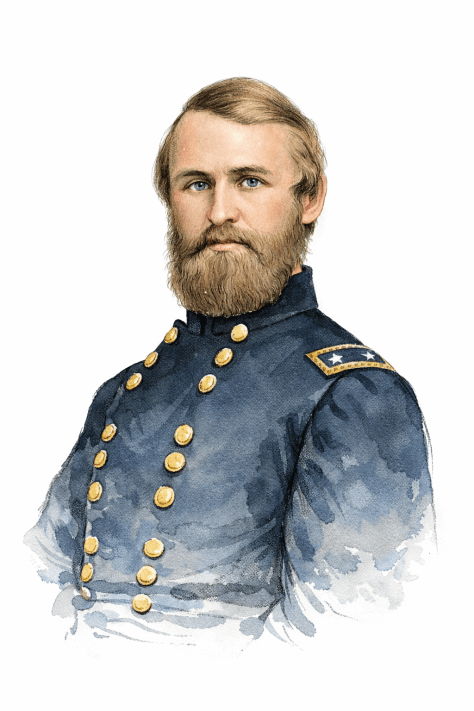

Our brave and beloved Gen. [Jacob Dolson] Cox 3 has been ordered back to Western Virginia to assume command of our forces there. We was very sorry to part with him. We would much rather went into a hard fight than to part with our gallant general who has been with us ever since the commencement of the war & who by his gentleman & soldier-like manner won the admiration & esteem of all who served under him. He left here for Washington last Sunday. He made us a short speech before leaving in which he said that he was very sorry to part with us and that as soon as he got to Washington, he would go to President Lincoln & Secretary Stanton & if possible obtain permission to take his Ohio Division back with him so you need not be surprised if you again hear of us being in Western Virginia shortly. We all want to go but it is not because we like the country. It is because our general is going & we want to be with him no matter where he goes.

Last Saturday we was reviewed by President Lincoln & General McClellan & staff. Old Abe did not make a very striking appearance. He is undoubtedly the ugliest an that I ever saw & owing to his being in company with so many fine looking officers made him look still worse.

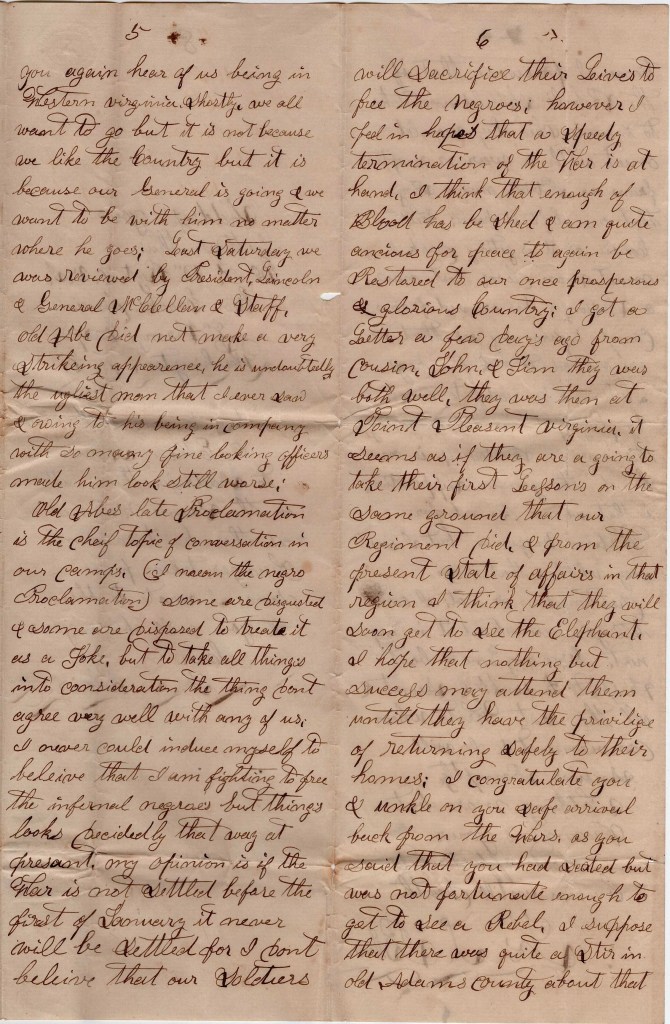

Old Abe’s late Proclamation is the chief topic of conversation in our camp (I mean the negro proclamation). Some are disgusted & some are disposed to treat it as a joke, but to take all things into consideration, the thing don’t agree very well with any of us. I never could induce myself to believe that I am fighting to free the infernal negroes but things look decidedly that way at present. My opinion is if the war is not settled before the first of January, it never wil be settled for I don’t believe that our soldiers will sacrifice their lives to free the negroes. However, I feel in hopes that a speedy termination of the war is at hand. I think that enough of blood has been shed & am quite anxious for peace to again be restored to our once prosperous & glorious country.

I got a letter a few days ago from cousin John & Jim. They was both well. They was then at Point Pleasant, Virginia. It seems as if they are a going to take their first lessons on the same ground that our regiment did. And from the present state of affairs in that region, I think that they will soon get to see the elephant. I hope that nothing but success may attend them until they have the privilege of returning safely to their homes.

I congratulate you & uncle on your safe arrival back from the wars, as you said that you had seated but was not fortunate enough to get to see a Rebel. I suppose that there was quite a stir in Old Adams County about that time. I presume that if the Rebels should undertake to invade Ohio, they would meet with a warm reception from our patriotic men & boys that are left at home.

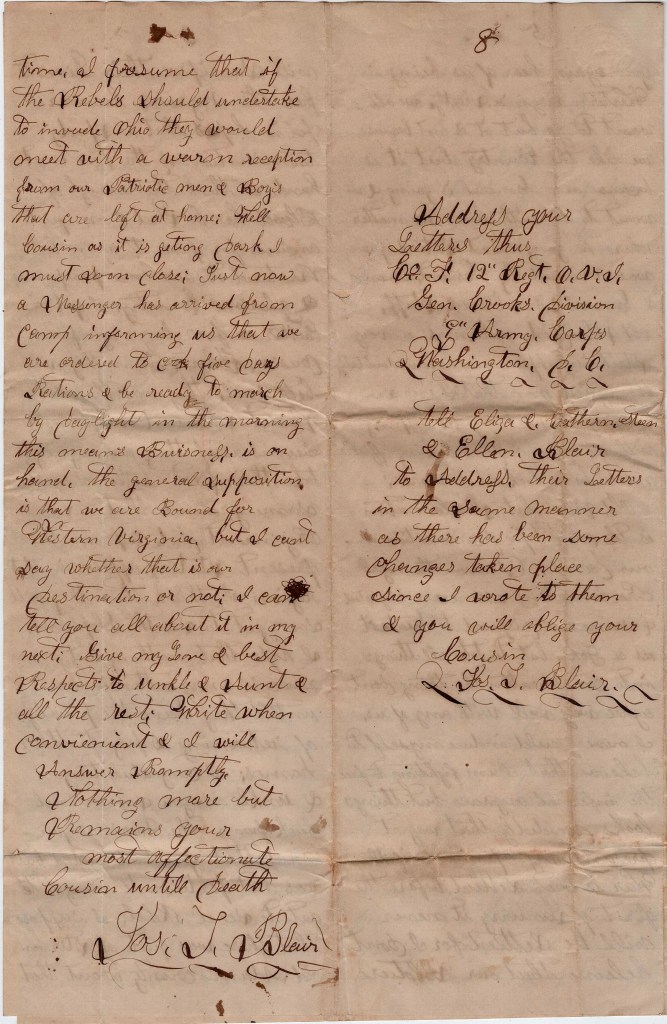

Well cousin, as it is getting dark, I must soon close. Just now a messenger has arrived from camp informing us that we are ordered to cook five days rations & be ready to march by daylight in the morning. This means business is on hand. The general supposition is that we are bound for Western Virginia but I can’t say whether that is our destination or not. I can tell you all about it in my next.

Give my love & best respects to uncle & aunt & all the rest. Write when convenient & I will answer promptly. Nothing more but remain your most affectionate cousin until death, — Jos. T. Blair

Address your letters thus. Co. F, 12th Regt. O. V. I., Gen. [George] Crook’s Division, 9th Army Corps, Washington D. C.

Tell Eliza & Catherine Steen & Ellen Blair to address their letters in the same manner as there has been some changes taken place since I wrote to them & you will oblige your cousin, — Jos. T. Blair

1 An after action report by Gen. Cox stated that the 12th OVI, in the center of the assault on South Mountain, “was obliged to advance several hundred yards over open pasture-ground, under a most galling fire from the edge of the woods which crowned the slope, and behind stone fences. The skirmishers of this regiment, advancing with admirable courage and firmness, drove in those of the enemy, and the regiment with loud hurrahs charged up the slope with the bayonet. The rebels stood firmly, and kept up a murderous fire until the advancing line was within a few feet of them, when they broke and fled over the crest into the shelter of a dense thicket skirting the other side.” [Source: Cox’s Official Reports, Antietam on the Web.]

2 In his after action report of the Battle of Antietam, Gen. Cox described the contested attempts of the 9th Army Corps to cross Burnside’s Bridge and eventually engage the enemy south of Sharpsburg where they met with initial success but were eventually overwhelmed by Rebel reinforcements. The 12th OVI held the extreme left of the Union line in the late afternoon assault, backing up the 16th Connecticut and the 4th Rhode Island.

3 Gen. Jacob Dolson Cox, a former divinity student at Oberlin College, was a staunch abolitionist from Ohio who rose to the rank of major general. “Despite Cox’s inexperience, then-commander of Ohio’s forces, Major General George B. McClellan, came to appreciate his talents, giving him an independent command in western Virginia shortly after the outbreak of hostilities between the North and the South. In 1861 and 1862, Cox played a central role in taking and holding for the Union what would become the new state of West Virginia. Cox’s forces took the new state’s future capital, Charleson, in mid-1861, helping ensure Union control of West Virginia for the remainder of the war. In mid-1862, Cox transferred to the Army of the Potomac for the Maryland Campaign, and in a period of three weeks, he underwent a dizzying ascent to corps command. On 14 September, he initiated the successful first assault at the Battle of South Mountain, which was the Union’s first victory in many months. When IX Corps commander Major General Jesse Reno was killed at that battle, Cox succeeded him. Three days later, at the pivotal Battle of Antietam, Cox would be the tactical commander of the Union left wing, made up entirely of the IX Corps. There, his forces almost succeeded in sweeping General Robert E, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia from the field. Only an unexpected assault on his left flank by Major General A.P. Hill’s division stopped Cox, though McClellan’s wrong-headed decision not to reinforce Cox at this critical moment sealed the Union’s fate that day.” [Source: The Army Historical Foundation, Jacob Dolson Cox]

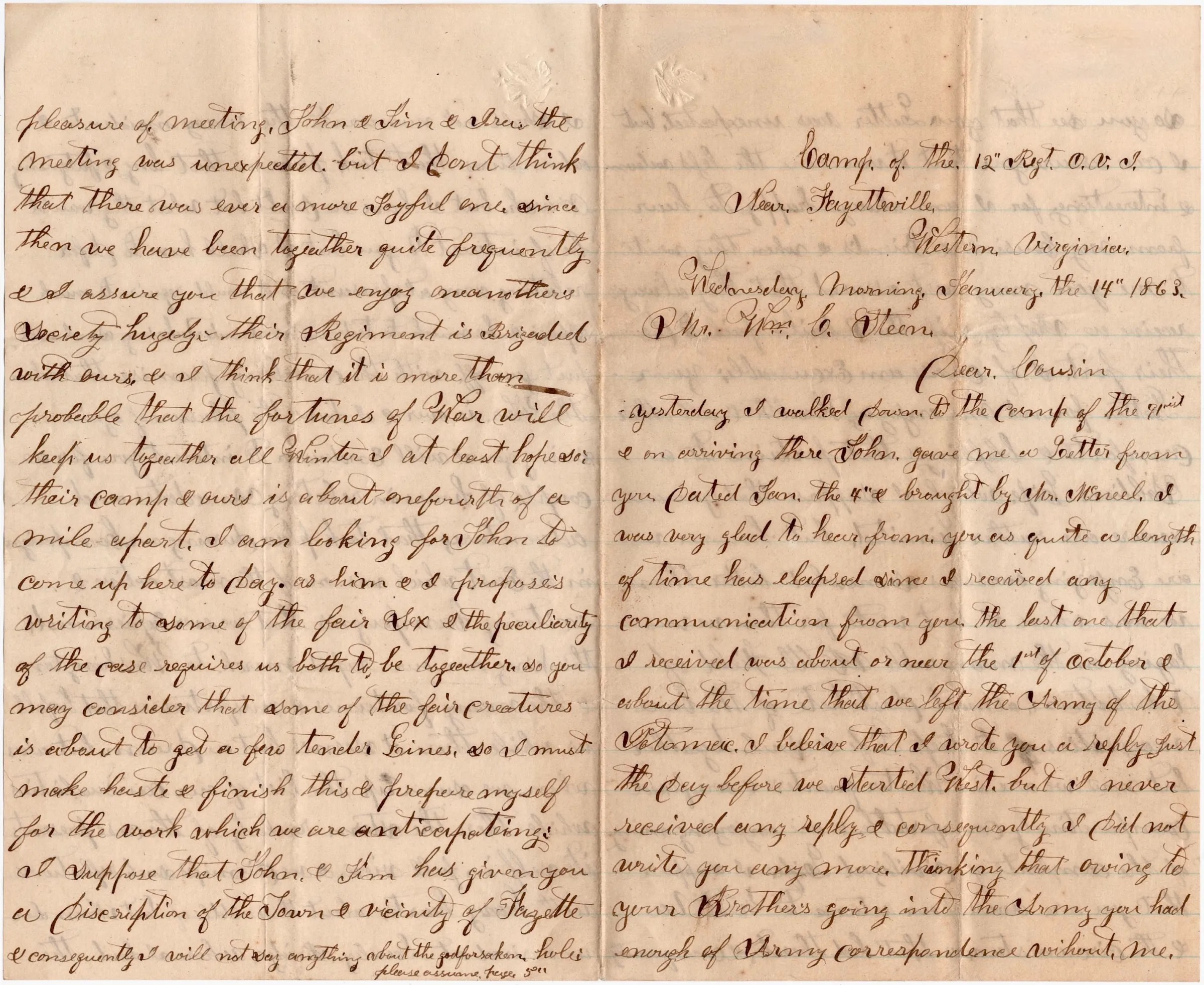

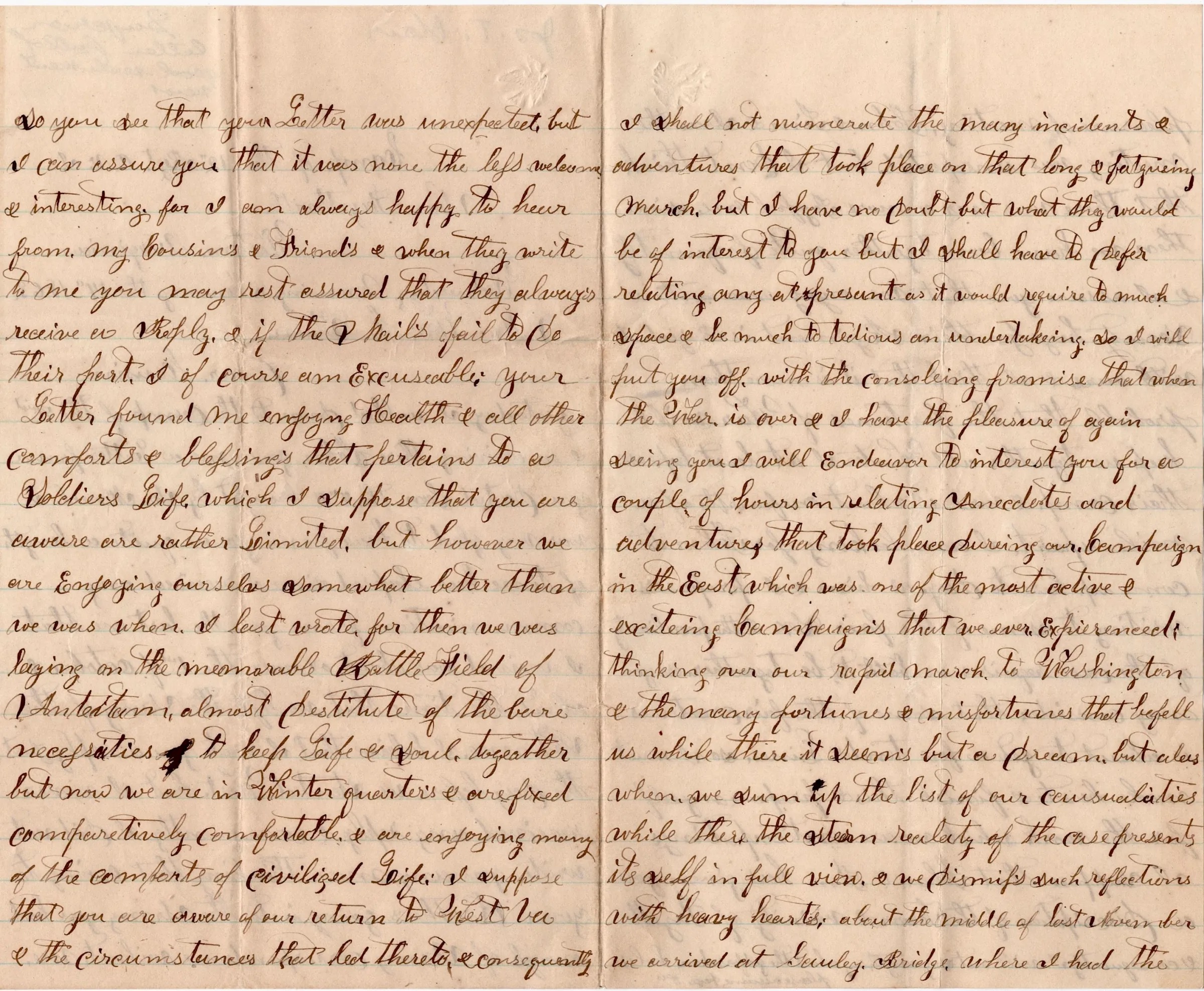

Letter 3

Camp of the 12th Regt. O.V. I.

Near Fayetteville, Western Virginia

Wednesday morning, February 14, 1863

Mr. Wm. C. Steen, dear cousin,

Yesterday I walked down to the camp of the 91st & on arriving there John gave me a letter from you dated January 4th & brought by Mr. McNeel. I was very glad to hear from you as quite a length of time has elapsed since I received any communication from you. The last one that I received was about or near the 1st of October & about the time that we left the Army of the Potomac. I believe that I wrote you a reply just the day before we started west but I never received any reply & consequently I did not write anymore thinking that owing to your brother’s going into the army you had enough of army correspondence without me so you see that your letter was unexpected. But I can assure you that it was none the less welcome & interesting for I am always happy to hear from my cousins & friends & when they write to me, you may rest assured that they always receive a reply. And if the mails fail to do their part, I of course am excusable.

Your letter found me enjoying health & all other comforts & blessings that pertain to a soldier’s life which I suppose that you are aware are rather limited, but however we are enjoying ourselves somewhat better than we was when I last wrote for then we was laying on the memorable battlefield of Antietam, almost destitute of the bare necessities to keep life and soul together. But now we are i winter quarters and are fixed comparatively comfortable & are enjoying many of the comforts of civilized life. I suppose that you are aware of our return to West Virginia & the circumstances that led thereto & consequently I shall not numerate the many incidents and adventures that took place on that long & fatiguing march, but I have no doubt but what they would be of interest to you. But I shall have to defer relating any at present as it would require too much space & be must too tedious an undertaking so I will put you off with the consoling promise that when the war is over & I have the pleasure of again seeing you, I will endeavor to interest you for a couple of hours in relating anecdotes and adventures that took place during our campaign in the East which was one of the most active and exciting campaigns that we ever experienced.

Thinking over our rapid march to Washington & the many fortunes and misfortunes that befell us while there it seems but a dream. But alas, when we sum up the list of our casualties while there, the stern reality of the case presents itself in full view and we dismiss such reflections with heavy hearts. About the middle of November we arrived at Gauley Bridge where I had the pleasure of meeting John & Jim & Ira. The meeting was unexpected, but I don’t think that there was ever a more joyful one. Since then we have been together quite frequently & I assure you that we enjoy one another’s society hugely. Their regiment is brigaded with ours & I think that it is more than probable that the fortunes of war will keep us together all winter. I at least hope so. Their camp and ours is about one fourth of a mile apart. I am looking for John to come up here today as him and I propose writing to some of the fair sex and the peculiarity of the case requires us both to be together so you may consider that some of the fair creatures is about to get a few tender lines. So I must make haste and finish this & prepare myself for the work which we are anticipating. I suppose that John and Jim has given you a description of the town and vicinity of Fayette & consequently I will not say anything about the God forsaken hole.

You cannot imagine how much I was surprised to hear of Eliza Steen being married, No, I can’t say that I was surprised to hear of her getting married for that was an event that I have long been looking to hear of, but what surprised me so much was to hear of her marrying Beverage. I was sure that the chosen one was a Mr. S. C. However, I hope that she may live a long and happy life & never regret the day that made her Mrs. Beverage. When you see them, wish them much joy for me. I will oblige your cousin Thompson.

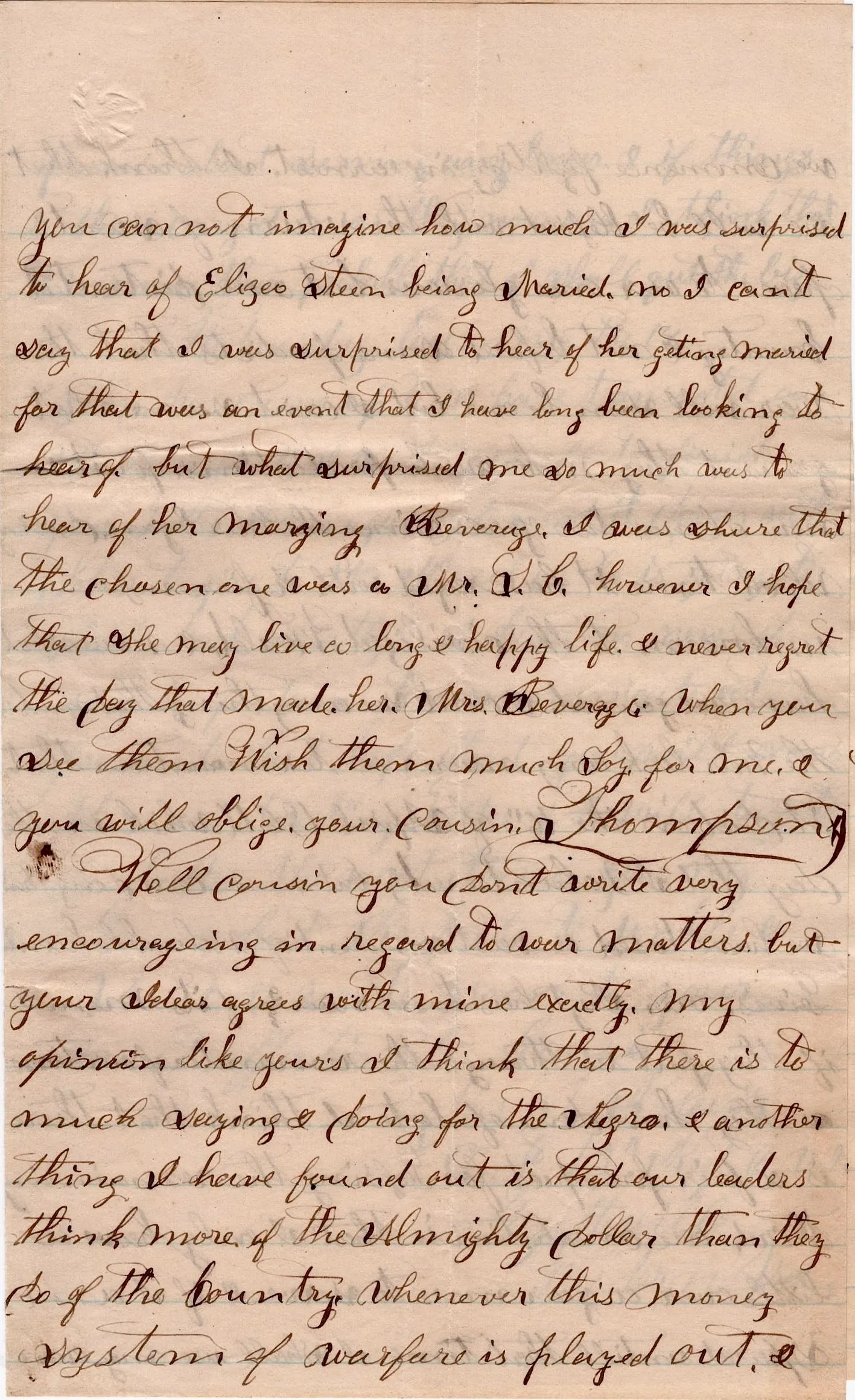

Well cousin, you don’t write very encouraging in regard to war matters but your ideas agree with mine exactly. My opinion like yours I think that there is too much saying and doing for the Negro. And another thing I have found out is that our leaders think more of the Almighty dollar than they do of the country. Whenever this money system of warfare is played out and we commence fighting in earnest, I think that we will be blessed with the return of sweet peace to our once glorious but now distracted country and not before. Some predicts that the war will soon be over but I can’t see on what ground they make such predictions for it is now almost two years since the war began during which time it has raged with a fierceness unknown to the civilized world. And now what have we gained? I can’t see anything that makes the war look any nearer to termination than it did on the 16th of April 1861 (which was the day I volunteered). But no one can deny that we have lost a vast amount of valuable human lives. Our regiment has lost near two-thirds of its men and if they put us through the remainder of our time as they have done of late, I think that there is a fair prospect for losing the remaining third. One consolation is that I only have a little over a year more to serve and if I am spared until that time, I shall us my own pleasure about serving any longer. And if things are then carried on as they now are, I think that is is more than probable that I shall quit the biz.

Wednesday evening, the 14th. John has come up and we have transacted our business and I seat myself to finish your letter. I am going to send it down with John to give to Mr. McNeel as he is going to start back shortly. I have no news of any importance to communicate at present but hope that you will excuse this uninteresting letter & I will try to do better the next time. Give my love and best respects to Uncle and Aunt, and write soon to your most affectionate cousin, — Joseph T. Blair, Co. F, 12th Regt. OVI, Fayetteville, Western Virginia

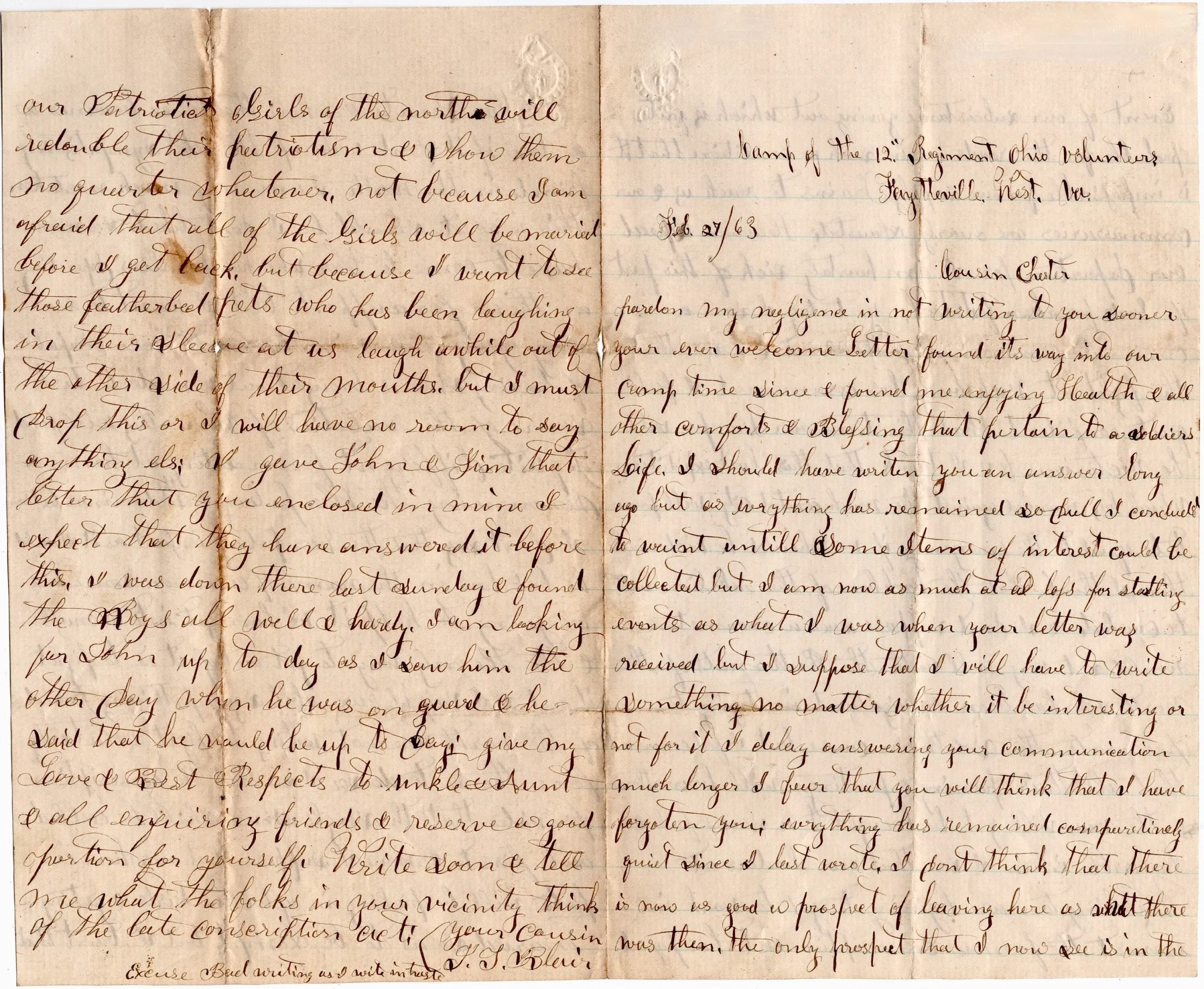

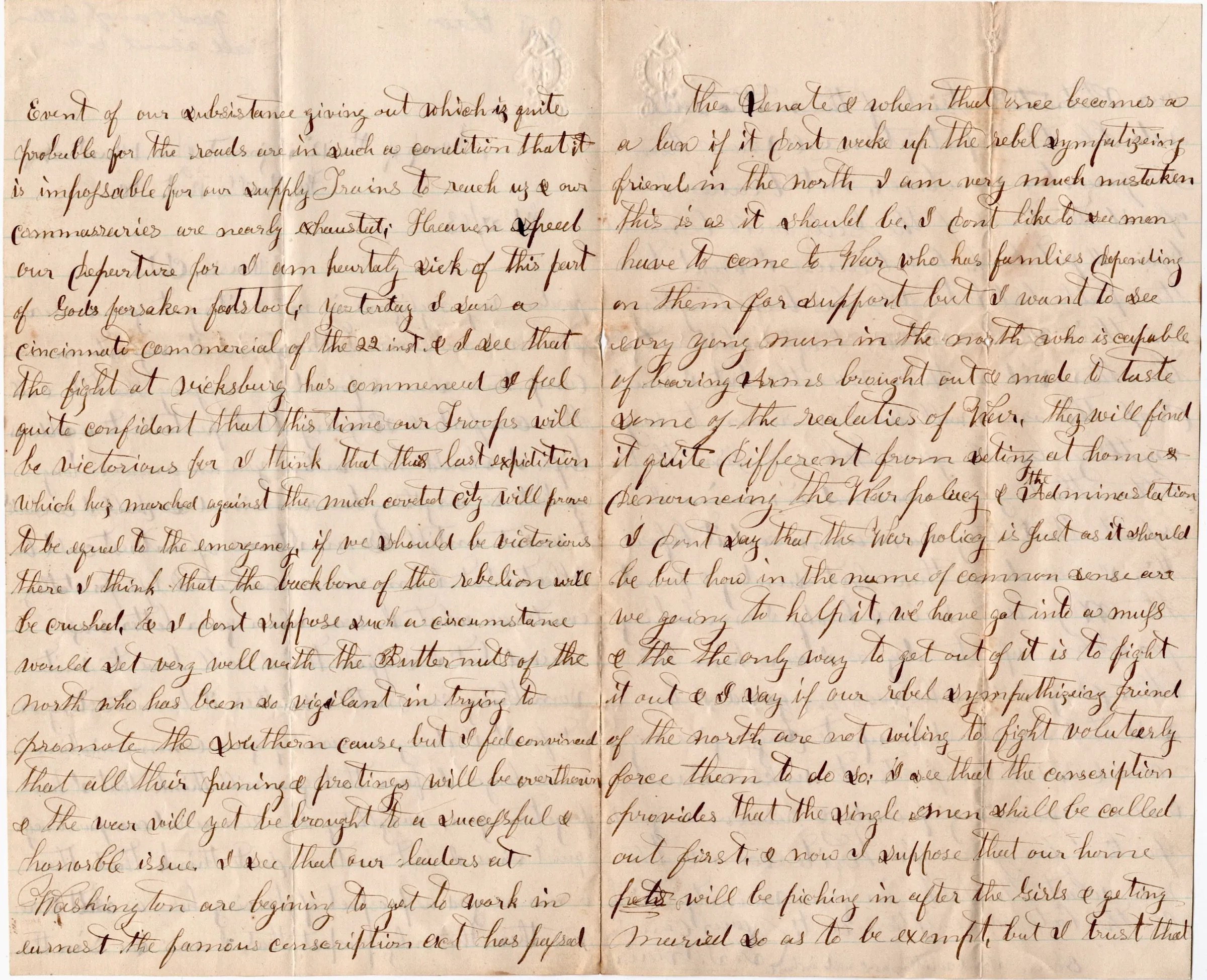

Letter 4

Camp of the 12th Regiment Ohio Volunteers

Fayetteville, West Va.

February 27, 1863

Cousin Chester,

Pardon my negligence in not writing to you sooner. Your ever welcome letter found its way into our camp time since & found me enjoying health & all other comforts & blessings that pertain to a soldier’s life. I should have written you an answer long ago but as everything has remained so dull, I concluded to wait until some items of interest could be collected but I am now as much at a loss for startling events as what I was when your letter was received. But I suppose that I will have to write something no matter whether it be interesting or not for if I delay answering your communication much longer I fear that you will think that I have forgotten you. Everything has remained comparatively quiet since I last wrote. I don’t think that there is now as good a prospect of leaving here as there was then. The only prospect that I now see is in the event of our subsistence giving out which is quite probable for the roads are in such a condition that it is impossible for our supply trains to reach us & our commissaries are nearly exhausted. Heaven speed our departure for I am heartily sick of this part of God’s forsaken footstool.

Yesterday I saw a Cincinnati Commercial of the 22nd inst. and I see that the fight at Vicksburg has commenced. I feel quite confident that this time our troops will be victorious for I think that this last expedition which has marched against the much coveted city will prove equal to the emergency. If we should be victorious there, I think that the backbone of the rebellion will be crushed & I don’t suppose such a circumstance would set very well with the Butternuts of the North who has been so vigilant in trying to promote the Southern cause. But I feel convinced that all their fuming and fretting will be overthrown & the war will yet be brought to a successful & honorable issue. I see that our leaders at Washington are beginning to get to work in earnest. The famous Conscription Act has passed the Senate & when that once becomes a law if it don’t wake up the rebel sympathizing friends in the North, I am very much mistaken. This is as it should be. I don’t like to see men have to come to war who has families depending on them for support, but I want to see every young man in the North who is capable of bearing arms brought out & made to taste some of the realities of war. They will find it quite different from sitting ay home & denouncing the war policy & the Administration. I can’t say that the war policy is just as it should be, but how in the name of common sense are we going to help it. We have got into a muss & the only way to get out of it is to fight it out & I say if our rebel sympathizing friends of the North are not willing to fight voluntarily, force them to do so.

I see that the conscription provides that the single men shall be called out first & now I suppose that our home pets will be pitching in after the girls & getting married so as to be exempt, but I trust that our patriotic girls of the North will redouble their patriotism & show them no quarter whatever—not because I am afraid that all of the girls will be married before I get back, but because I want to see those featherbed pets who has been laughing in their sleeve at us laugh awhile out of the other side of their mouths.

But I must stop this or I will have no room to say anything else. I gave John & Jim that letter that you enclosed in mine & expect that they have answered it before this. I was down there last Sunday and found the boys all well and hardy. I am looking for John up today as I saw him the other day when he was on guard & he said that he would be up today. Give my love to& best respects to Uncle & Aunt & all enquiring friends & reserve a good portion for yourself. Write soon and tell me what the folks in your vicinity think of the late Conscription Act. your cousin, — J. T. Blair

Excuse bad writing as I write in haste.

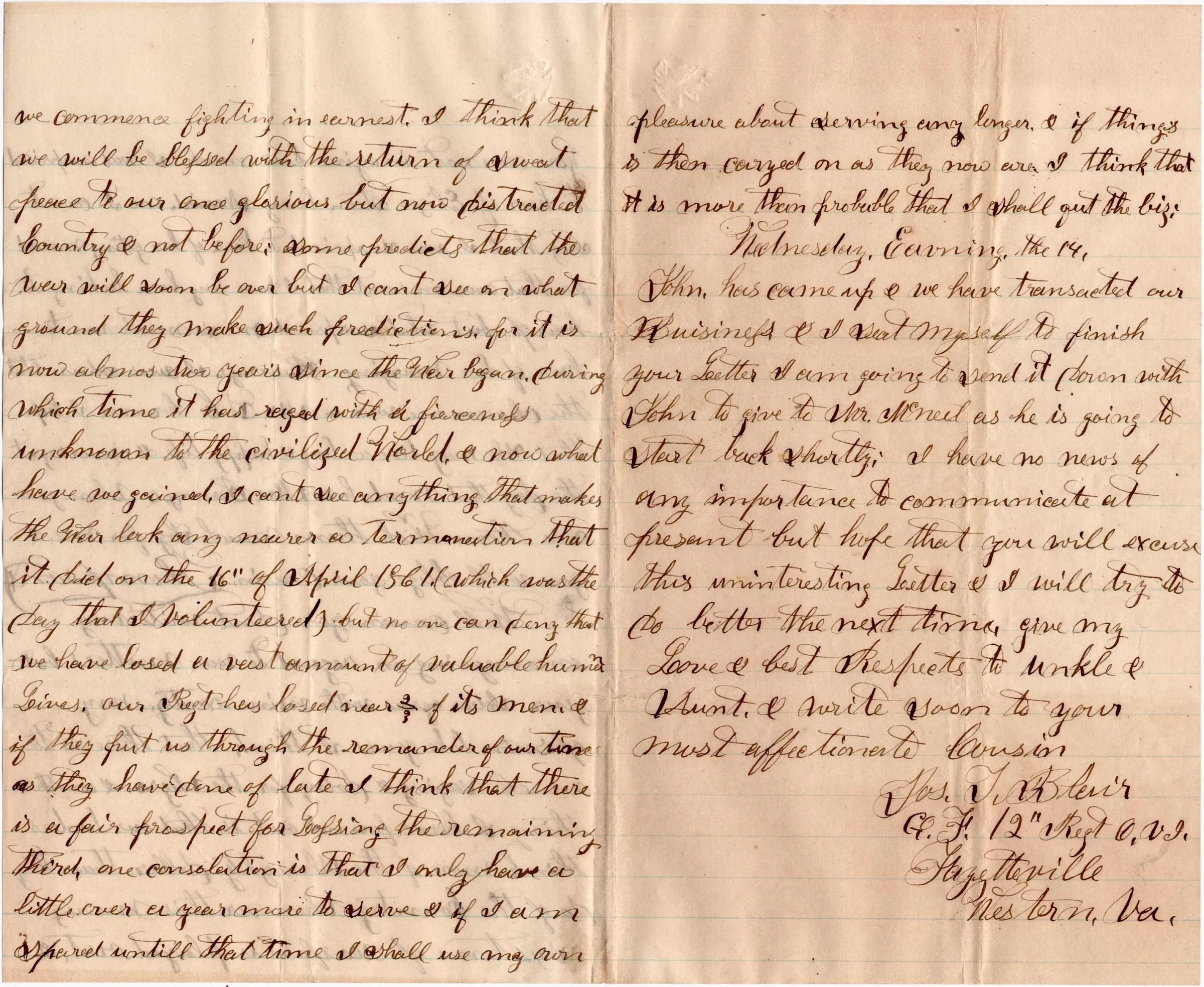

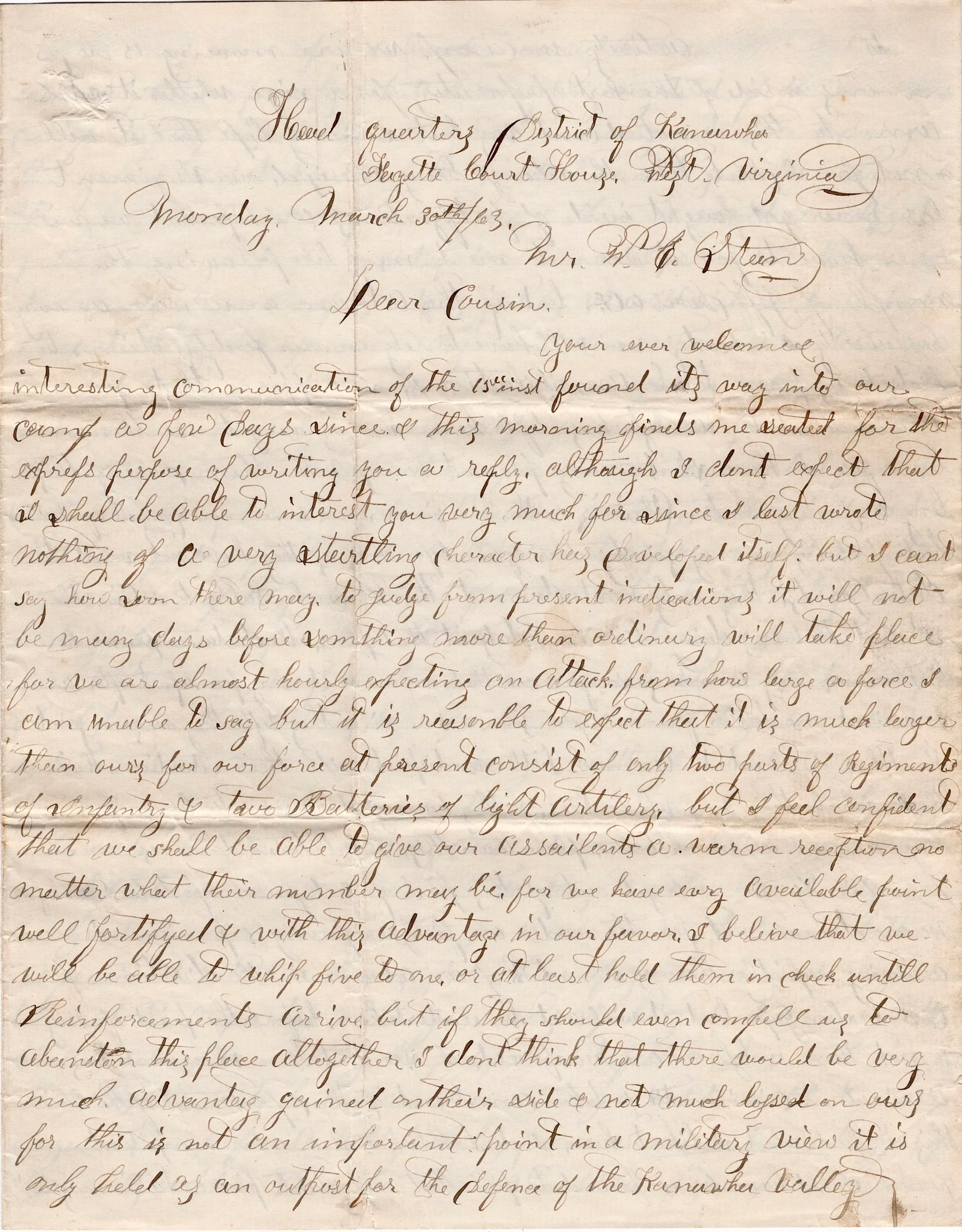

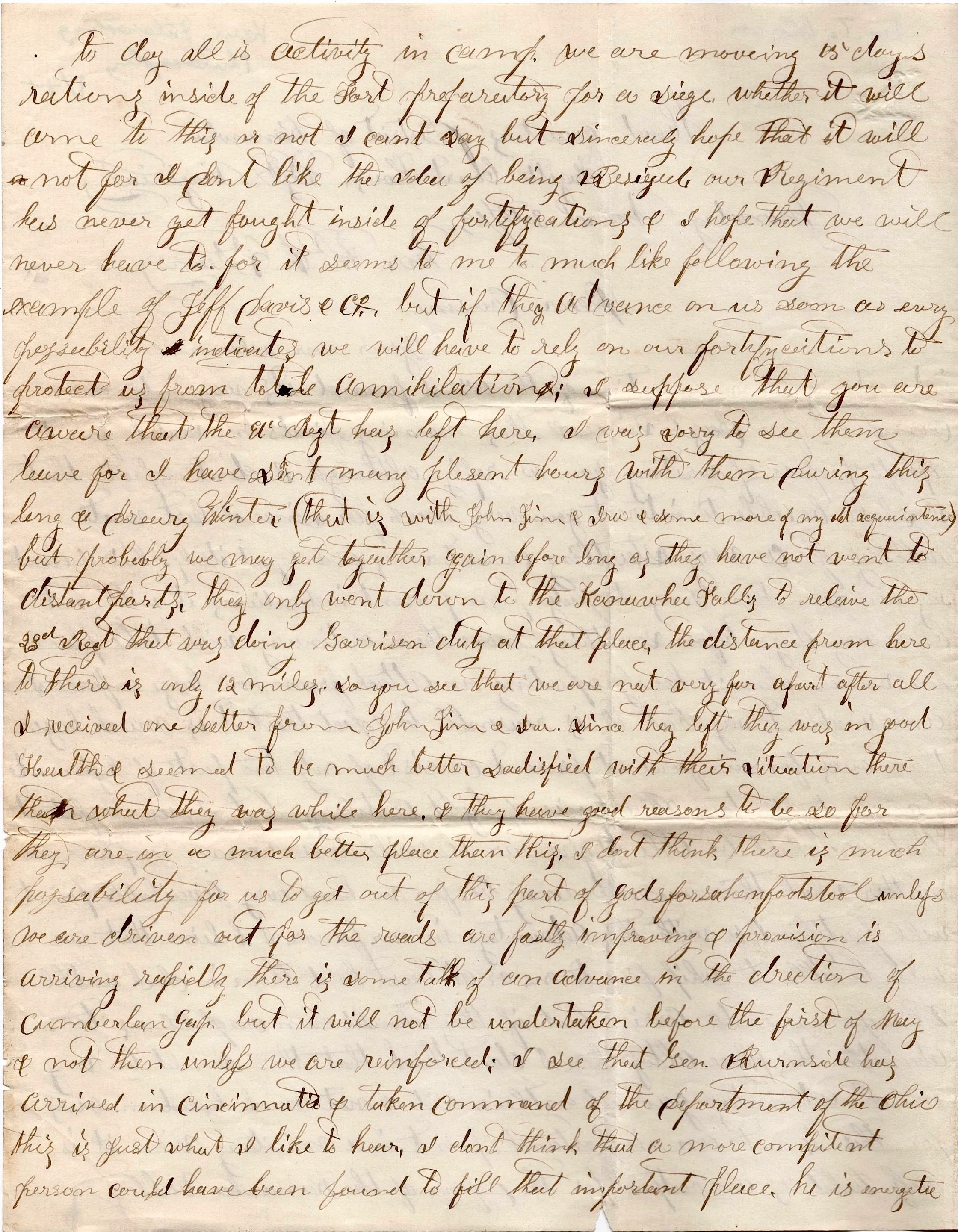

Letter 5

Headquarters District of Kanawha

Fayette Court House, West Virginia

Monday, March 30, 1863

Mr. W. C. Steen, dear cousin,

Your ever welcome, interesting communication of the 15th inst. found its way into our camp a few days since & this morning finds me seated for the express purpose of writing you a reply although I don’t expect that I shall be able to interest you very much for since I last wrote nothing of a very startling character has developed itself, but I can’t say how soon there may. To judge from present indications, it will not be many days before something more than ordinary will take place for we are almost hourly expecting an attack from how large a force I am unable to say. But it is reasonable to expect that it is much larger than ours for our force at present consists of only two parts of regiments of infantry & two batteries of light artillery. But I feel confident that we shall be able to whip five to one, or at least hold them in check until reinforcements arrive. But if they should even compel us to abandon this place altogether, I don’t think that there would be very much advantage gained on their side & not much lost on ours for this is not an important point in a military view it is only held as an outpost for the defense of the Kanawha Valley.

Today all is activity in camp. We are moving 15 days rations inside of the fort preparatory fora siege. Whether it will come to this or not, I can’t say, but sincerely hope that it will not for I don’t like the idea of being besieged. Our regiment has never yet fought inside of fortifications & I hope that we will never have to for it seems to me too much like following the example of Jeff Davis & Co., but if they advance on us soon as every possibility indicates, we will have to rely on our fortifications to protect us from total annihilation.

I suppose that you are aware that the 91st Regiment has left here. I was sorry to see them leave for I have spent many pleasant hours with them during this long and dreary winter (that is with John, Jim & Ira and some more of my old acquaintances) but probably we may get together again before long as they have not went to distant parts. They only went down to the Kanawha Falls to relieve the 23rd Regiment that was doing garrison duty at that place. The distance from here to there is only 12 miles so you see that we are not very far apart after all. I received one letter from John, Jim & Ira since they left. They was in good health and seemed to be much better satisfied with their situation there than what they was while here and they have good reasons to be so for they are in a much better place than this. I don’t think there is much possibility for us to get out of this part of God forsaken footstool unless we are driven out for the roads are fastly improving and provision is arriving rapidly. There is some talk of an advance in the direction of Cumberland Gap but it will not be undertaken before the first of May & not then unless we are reinforced.

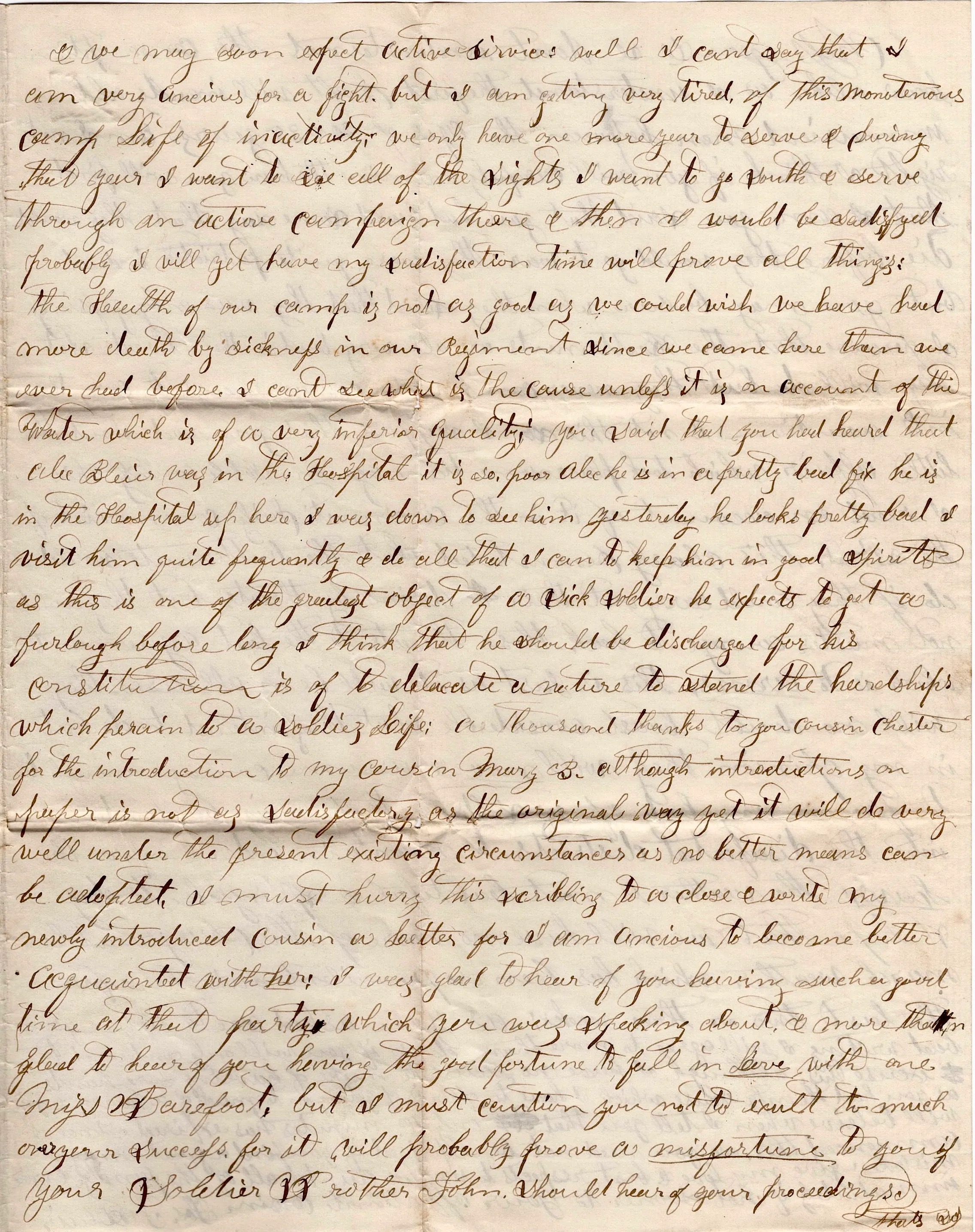

I see that Gen. Burnside has arrived in Cincinnati & taken command of the Department of the Ohio. This is just what I like to hear. I don’t think that a more competent person could have been found to fill that important place. He is energetic & we may soon expect active service. Well I can’t say that I am very anxious for a fight but I am getting very tired of this monotonous camp life of inactivity. We only have one more year to serve and during that year I want to see all of the sights. I want to go south & serve through an active campaign there & then I will be satisfied. Probably I will get my satisfaction. Time will prove all things.

The health of our camp is not as good as we could wish. We have had more death by sickness in our regiment since we came here than we ever had before. I can’t see what is the cause unless it is on account of the water which is of a very inferior quality. You said that you had heard that Alec Blair was in the hospital. It is so. Poor Alec. He is in a pretty bad fix. He is in the hospital up here. I was down to see him yesterday. He looks pretty bad. I visit him quite frequently & do all I can to keep him in good spirits as this is one of the greatest object of a sick soldier. He expects to get a furlough before long. I think that he should be discharged for his constitution is of too delicate a nature to stand the hardships which pertain to a soldier’s life.

A thousand thanks to you cousin Chester for the introduction to my cousin Mary B. Although introductions on paper is not as satisfactory as the original way, yet it will do very well under the present existing circumstances as no better means can be adopted. I must hurry this scribbling to a close to write my newly introduced cousin a letter for I am anxious to become better acquainted with her. I was very glad to hear of you having such a good time at that party which you was speaking about & more than glad to hear you having the good fortune to fall in love with one Miss Barefoot. But I must caution you not to exult too much over your success for it will probably prove a misfortune to you if your soldier brother John should hear of your proceedings.

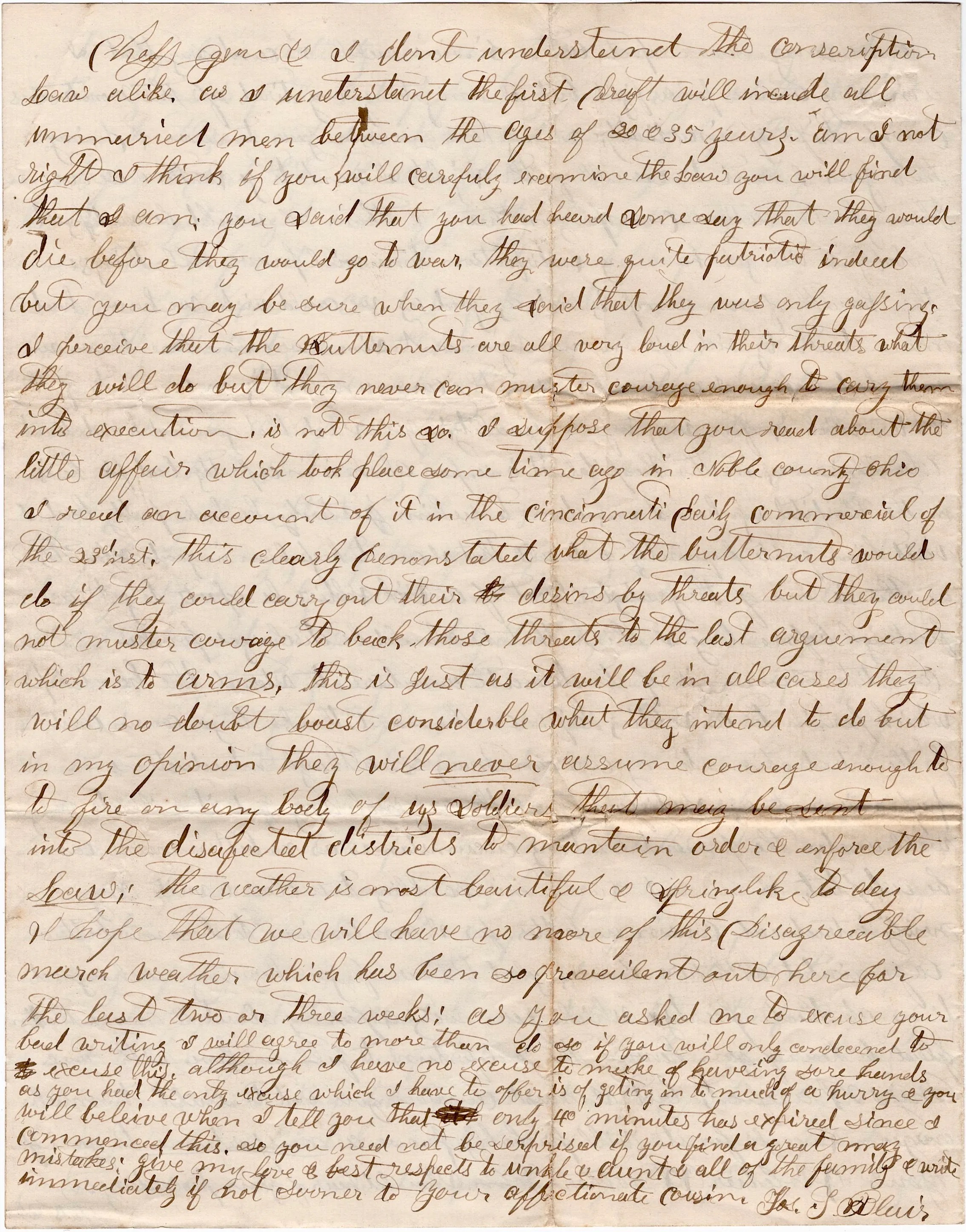

Chester, you and I don’t understand the Conscription Law alike. As I understand, the first draft will include all unmarried men between the ages of 20 and 35 years. Am I not right? I think if you will carefully examine the law, you will find that I am. You said that you had heard some say that they would die before they would go to war. They were quite patriotic indeed but you may be sure when they said that they was only gassing. I perceive that the Butternuts are all very loud in their threats what they will do, but they never can muster courage enough to carry them into execution. Is not this so? I suppose that you read about the little affair which took place some time ago in Noble county, Ohio. I read an account of it in the Cincinnati Daily Commercial of the 23rd inst. This clearly demonstrated what the Butternuts would do if they could carry out their designs by threats but they could not muster courage to back those threats to the last argument which is to arms. This is just as it will be in all cases. They will no doubt boast considerable what they intend to do but in my opinion they will never assume courage enough to fire on anybody of us soldiers that may be sent into the disaffected districts to maintain order and enforce the law.

The weather is most beautiful and spring like today. I hope that we will have no more of this disagreeable March weather which has been so prevalent out here for the last two or three weeks. As you asked me to excuse your bad writing, I will agree to more than do so if you will only condescend to excuse this, although I have no excuse to make of having sore hands as you had. The only excuse which I have to offer is of getting in too much of a hurry & you will believe when I tell you that only 40 minutes has expired since I commenced this so you need not be surprised if you find a great many mistakes. Give my love and best respects to Uncle & Aunt and all the family. Write immediately if not sooner to your affectionate cousin, — Jos. T. Blair

Letter 6

Fayette Court House, West Virginia

April 29, 1863

My dear cousin Chester,

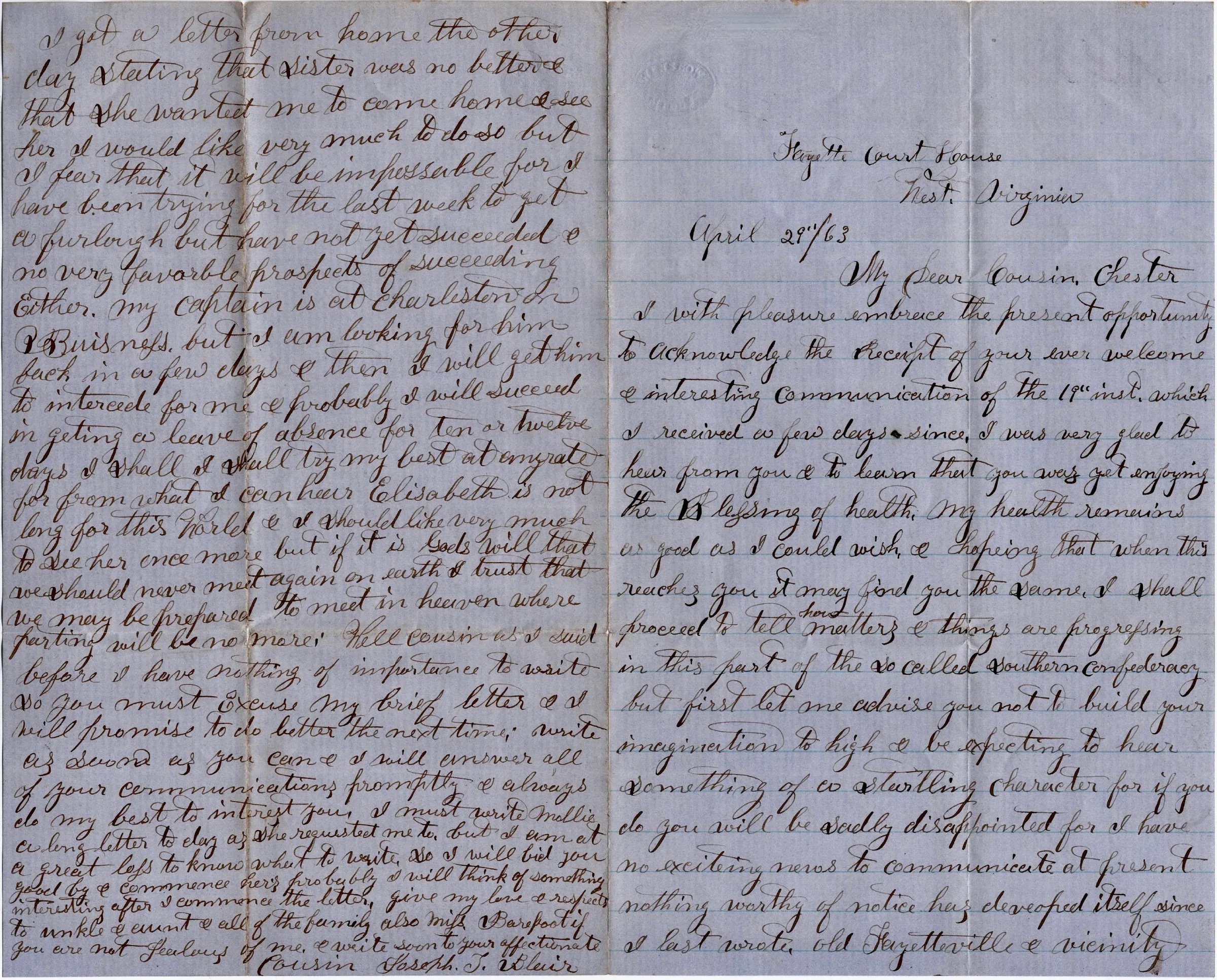

I with pleasure embrace the present opportunity to acknowledge the receipt of your ever welcome and interesting communication of the 19th inst. which I received a few days since. I was very glad to hear from you and to learn that you was yet enjoying the blessing of health. My health remains as good as I could wish & hoping that when this reaches you it may find you the same.

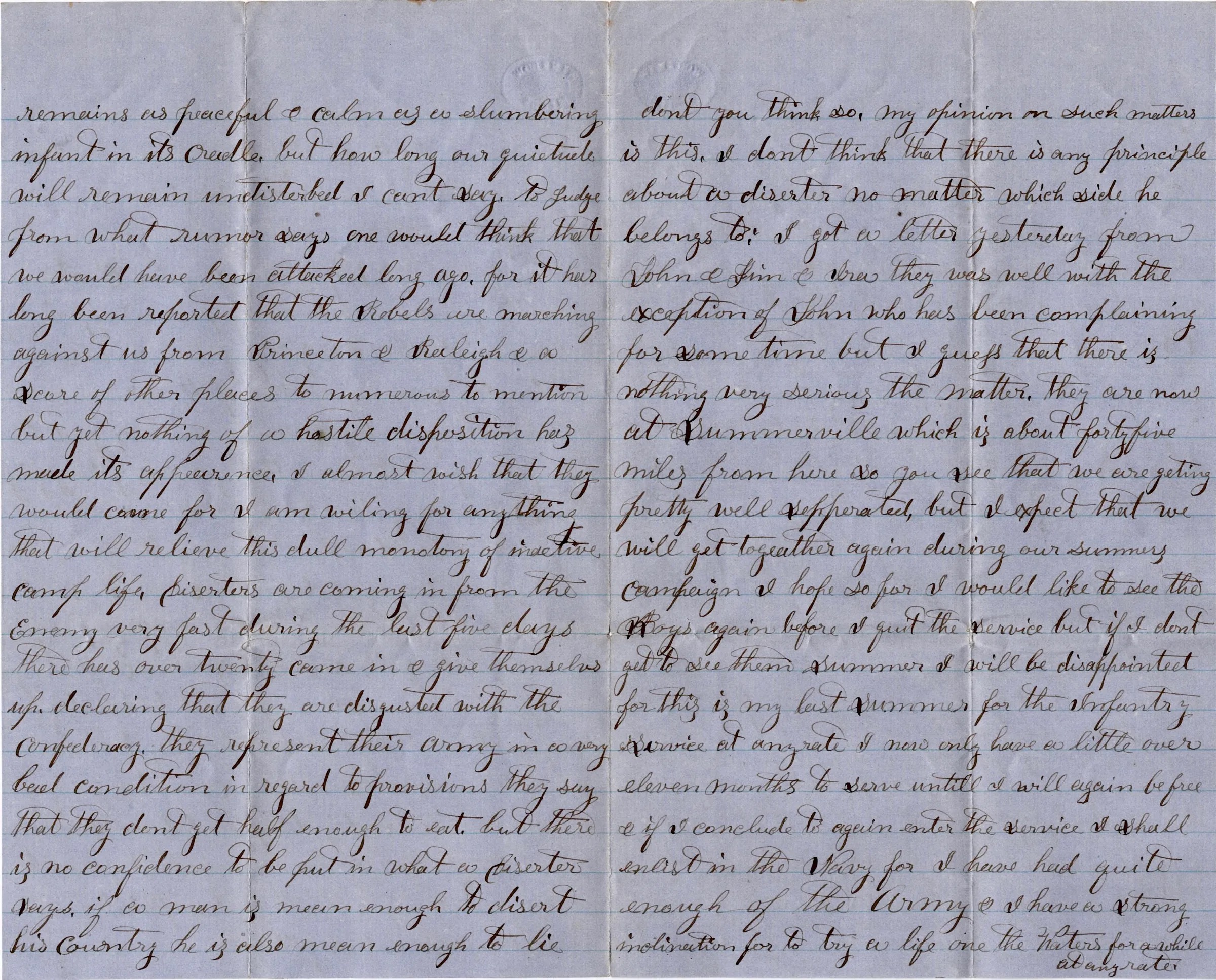

I shall proceed to tell how matters and things are progressing in this part of the so called Southern Confederacy but first let me advise you not to build your imagination too high and be expecting to hear something of a startling character for if you do, you will be sadly disappointed for I have no exciting news to communicate at present. Nothing worthy of notice has developed itself since I last wrote. Old Fayetteville & vicinity remains as peaceful and calm as a slumbering infant in its cradle. But how long our quietude will remain undisturbed I can’t say. To judge from what rumor says, one would think that we would have been attacked long ago, for it has long been reported that the Rebels are marching against us from Princeton & Raleigh & a score of other places too numerous to mention. But yet nothing of a hostile disposition has made its appearance. I almost wish that they would come for I am willing for anything that will relieve this dull monotony of inactive camp life.

Deserters are coming in from the enemy very fast during the last five days. There has over twenty come in and give themselves up declaring that they are disgusted with the Confederacy. They represent their army in a very bad condition in regard to provisions. They say that they don’t get half enough to eat but there is no confidence to be put in what a deserter says. If a man is mean enough to desert his country, he is also mean enough to lie. Don’t you think so? My opinion on such matters is this. I don’t think that there is any principle about a deserter no matter which side he belongs to.

I got a letter yesterday from John & Jim & Ira. They was well with the exception of John who has been complaining for some time but I guess that there is nothing very serious the matter. They are now at Summerville which is about 45 miles from here so you see that we are getting pretty well separated. But I expect that we will get together again during our summer campaign.I hope so for I would like to see the boys again before I quit the service. But if I don’t get to see them summer, I will be disappointed for this is my last summer—for the infantry service at any rate. I now only have a little over 11 months to serve until I will again be free & if I conclude to again enter the service, I shall enlist in the Navy for I have had quite enough of the army & I have a strong inclination for to try a life on the waters for awhile at any rate.

I got a letter from home the other day stating that sister was no better & that she wanted me to come home and see here. I would like very much to do so but I fear that it will be impossible for I have been trying for the last week to get a furlough but have not yet succeeded & no very favorable prospects of succeeding either. My captain is at Charlestown on business but I am looking for him back in a few days and then I will get him to intercede for me and probably I will succeed in getting a leave of absence for ten or twelve days. I shall try my best at any rate for from what I can here, Elizabeth is not long for this world & I should like very much to see her once more. But if it is God’s will that we should never meet again on earth, I trust that we may be prepared to meet in heaven where parting will be no more…

Your affectionate cousin, — Joseph T. Blair

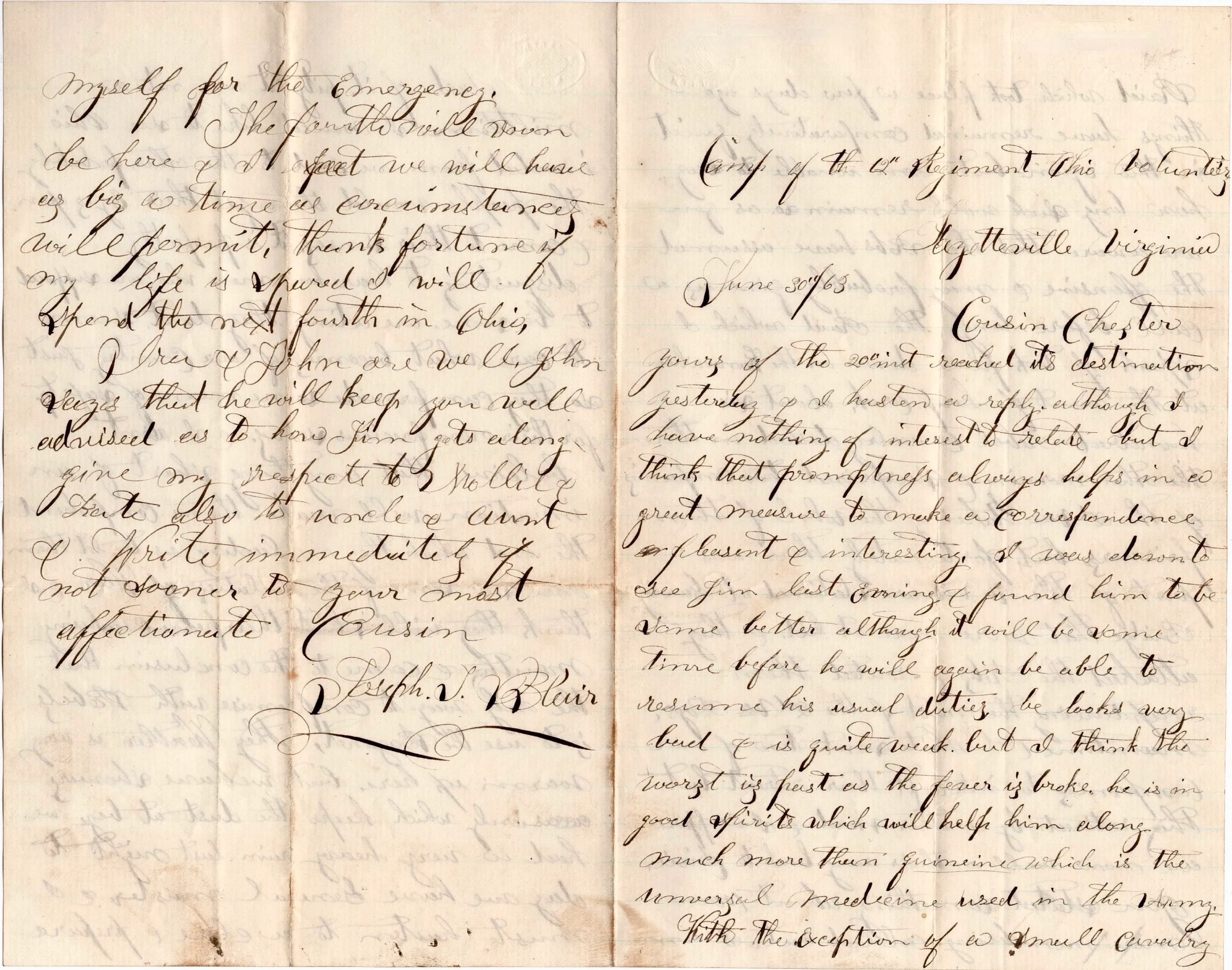

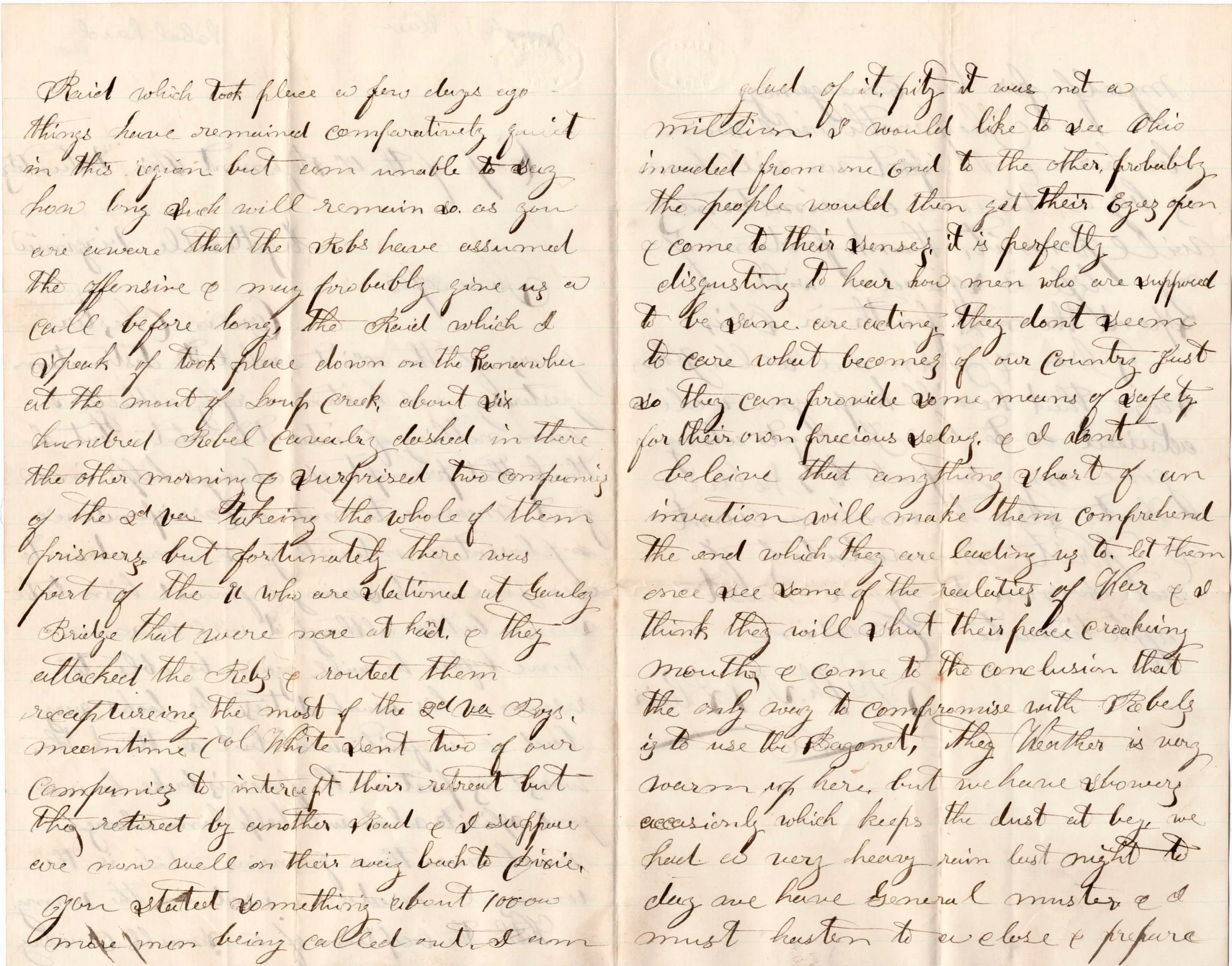

Letter 7

Cousin Chester,

Yours of the 20th inst. reached its destination yesterday & I hasten a reply although I have nothing of interest to relate but I think that promptness always helps in a great measure to make a correspondence pleasant & interesting. I was down to see Jim last evening & found him to be some better although it will be some time before he will again be able to resume his usual duties. He looks very bad & is quite weak but I think the worst is past as the fever is broke. He is in good spirits which will help him along much ore than quinine which is the universal medicine used in the army.

With the exception of a small cavalry raid which took place a few days ago, things have remained comparatively quiet in this region but am unable to say how long such will remain so as you are aware that the Rebs have assumed the offensive and may probably give us a call before long. The raid which I speak of took place down on the Kanawha at the mouth of Loup Creek. About 600 Rebel cavalry dashed in there the other morning and surprised two companies of the 2nd Virginia taking the whole of them prisoners but fortunately there was part of the 91st who was stationed at Gault Bridge that were near at hand and they attacked the Rebs and routed them, recapturing the most of the 2nd Virginia boys. Meantime Col. White sent two of our companies to intercept their retreat but they retired by another road & I suppose are now well in their way back to Dixie.

You stated something about 100,000 more men being called out. I am glad of it. Pity it was not a million. I would like to see Ohio invaded from one end to the other. Probably the people would get their eyes open & come to their senses. It is perfectly disgusting to hear how men who are supposed to be sane are acting. They don’t seem to care what becomes of our country just so they can provide some means of safety for their own precious selves. I don’t believe that anything short of an invasion will make them comprehend the end which they are leveling us to. Let them once see some of the realities of war and I think they will shut their peace croaking mouth and come to the conclusion that the only way to compromise with Rebels is to use the bayonet.

The weather is very warm up here but we have showers occasionally which keeps the dust at bay. We had a very heavy rain last night. Today we have general muster & I must hasten to a close and prepare myself for the emergency.

The 4th [of July] will soon be here & I expect we will have as big a time as circumstances will permit. Thank fortune if my life is spared I will spend the next 4th in Ohio.

Ira and John are well. John says that he will keep you well advised as to how Jim gets along. Give my respects to Mollie & Kate. Also to Uncle and Aunt & write immediately if not sooner to your most affectionate cousin, — Joseph T. Blair

These are the original images of Joseph T. Blair as they appeared on Mosby’s Raiders with Eric Buckland’s Facebook Page with the following comment by eric:

“PVT Joseph T. Blair was “killed by bushwhackers” near Fayetteville, WV while riding with on November 10, 1863, so he may never have come up against Mosby’s Ranger. there is no doubt that some of his comrades did later on!”