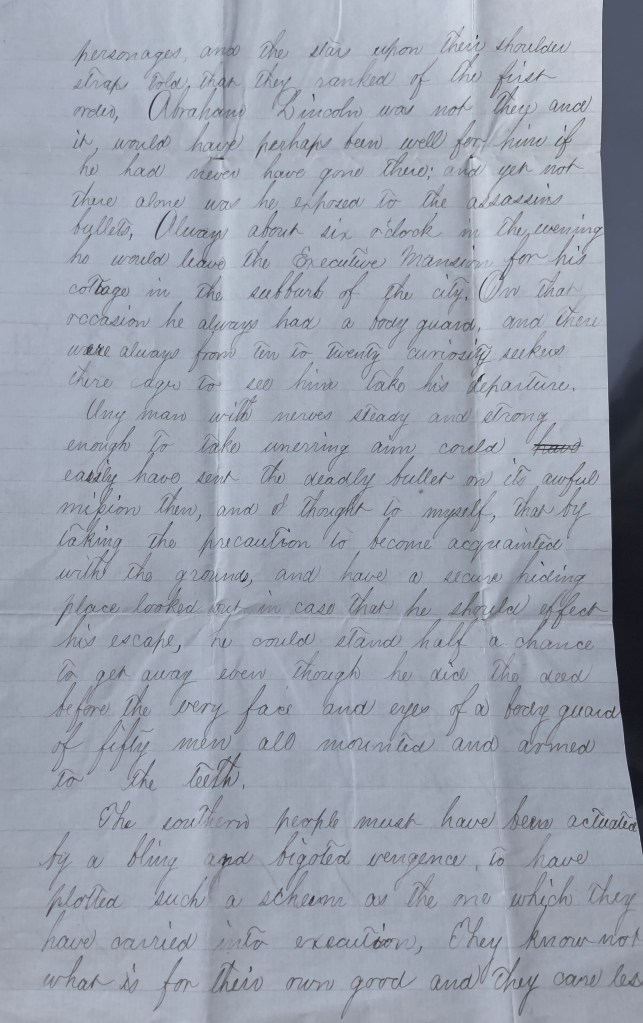

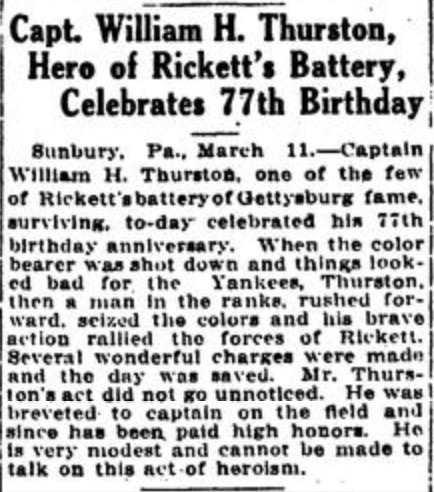

These letters were written by Lt. William Henry Thurston (1838-1924), the son of Isreal Thurston (1809-1888) and Abigail Persing (1817-1892) of Shamokin, Pennsylvania. William worked as a blacksmith before he enlisted and was mustered into service on July 8, 1861 as a private with the Forty-Third Regiment, Battery F, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery. He was promoted to 1st Lieutenant on April 22, 1865 and mustered out with the Battery on June 9, 1865.

He wrote the last two letters to his fiancé, Laura Morgan (1845-1928), whom he married in 1865. Laura was the daughter of John Campbell Morgan (1818-1887) and Mary Catharine Weimer (1825-1885) of Sunbury, Northumberland county, Pennsylvania.

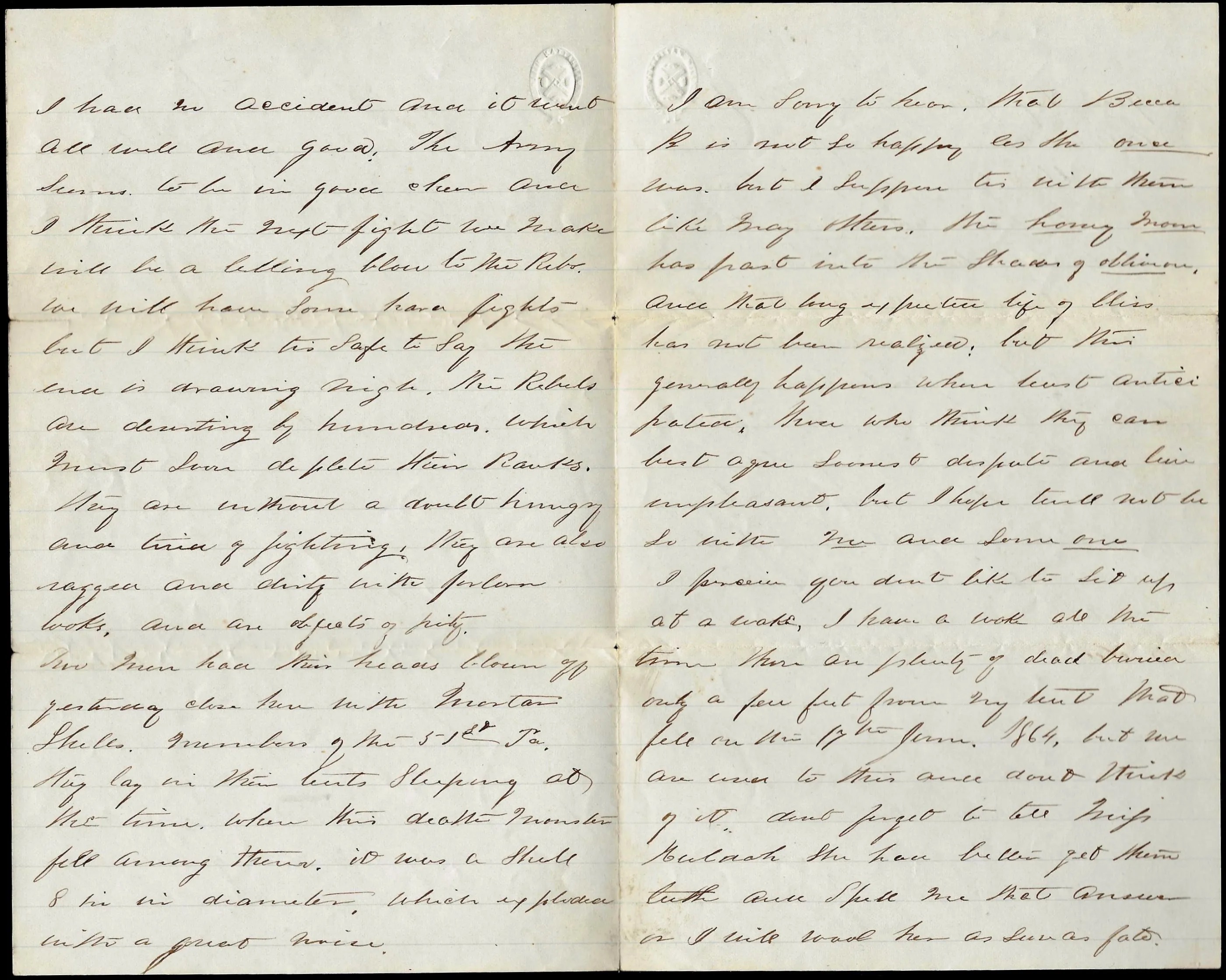

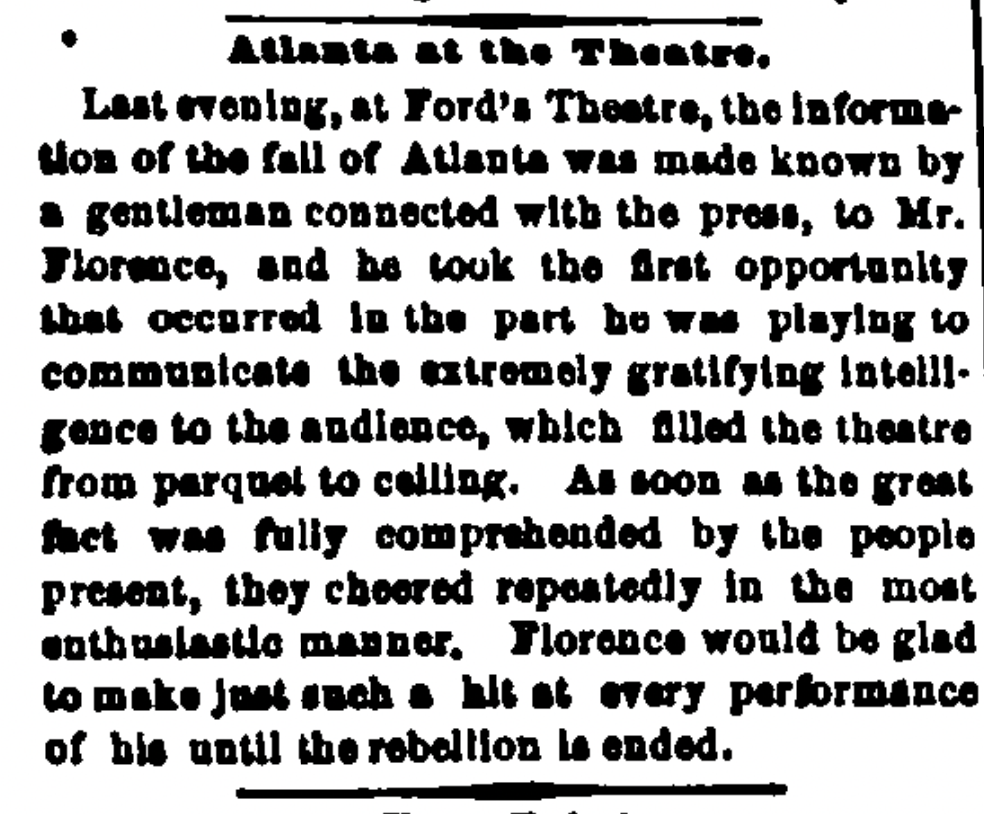

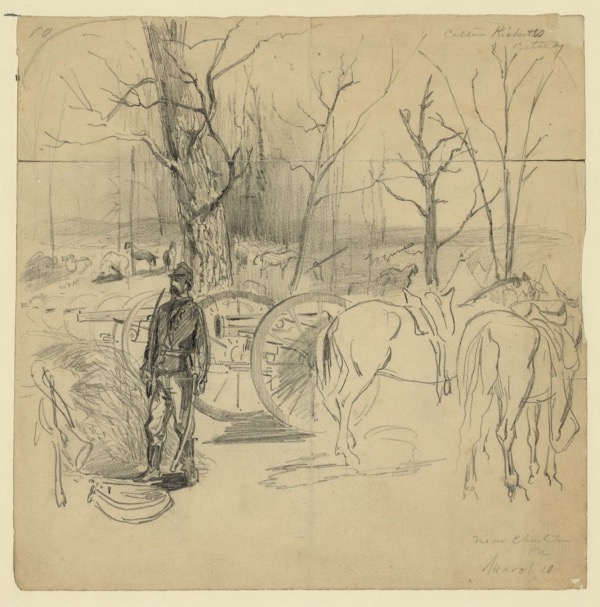

At Gettysburg, Capt. Robert B. Ricketts brought 144 men to the field on 2 July 1863 serving six Ordnance Rifles. During the battle they suffered 6 killed, 14 wounded, and three missing. They took a position on Benner’s Hill and at dusk they repulsed a Rebel assault upon the battery in desperate hand-to-hand combat after every round of canister had been fired. The newspaper clipping indicates that Thurston was recognized for his bravery in the action.

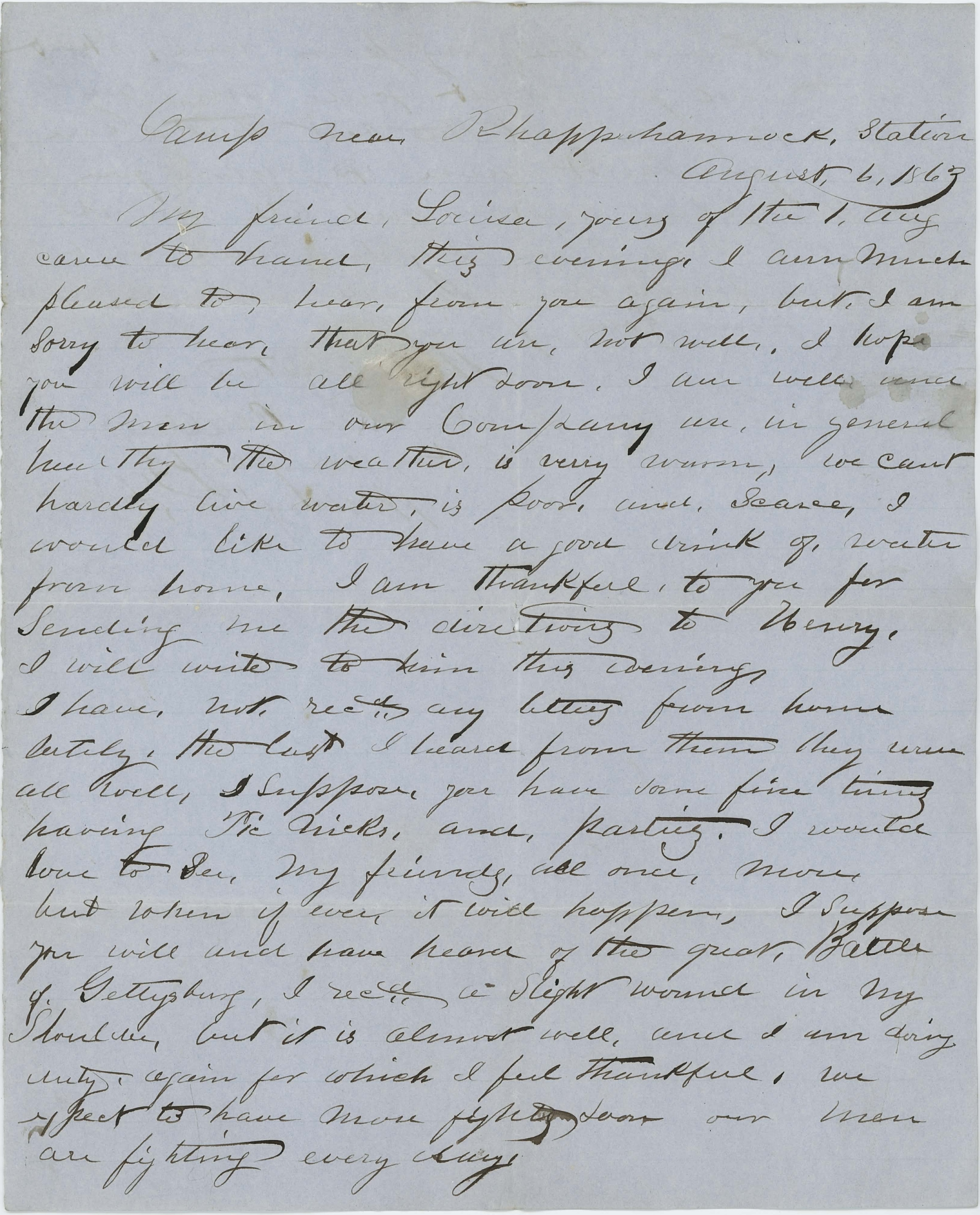

Letter 1

[Note: This letter is from the collection of Robert May and was made available for transcription and publication of Spared & Shared by express consent.]

Camp near Rappahannock Station

August 6, 1863

My friend Louisa,

Yours of the 1st August came to hand this evening. I am much pleased to hear from you again but I am sorry to hear that you are not well. I hope you will be all right soon. I am well and the men in our company are, in general, healthy. The weather is very warm. We can’t hardly live, water is poor and scarce. I would like to have a goo drink of water from home.

I am thankful to you for sending me the directions to Henry. I will write to him this evening. I have not received any letters from home lately. The last I heard from them they were all well. I suppose you have some fine times having picnics and parties. I would love to see my friends all once more but when, if ever, it will happen.

I suppose you will and have heard of the great Battle of Gettysburg. I received a slight wound in my shoulder but it is almost well and I am doing duty again for which I feel thankful. We expect to have more fights soon. Our men are fighting every day.

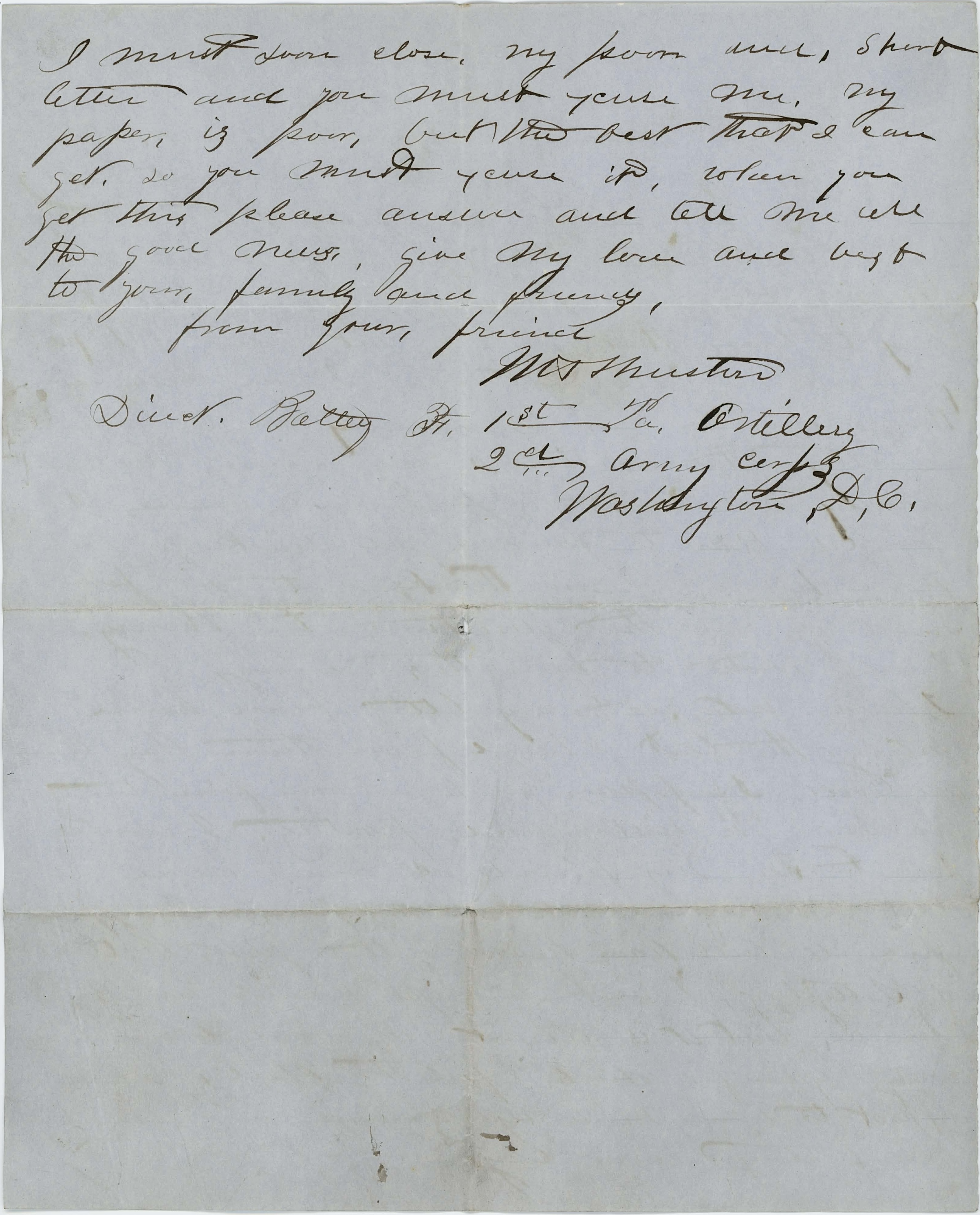

I must soon close my poor and short letter and you must excuse me. My paper is poor but the best that I can get so you must excuse it. When you get this, please answer and tell me all the good news. Give my love and best to your family and friends. From your friend, — W. H. Thurston

Direct Battery F, 1st Pennsylvania Artillery, 2nd Army Corps, Washington D. C.

Letter 2

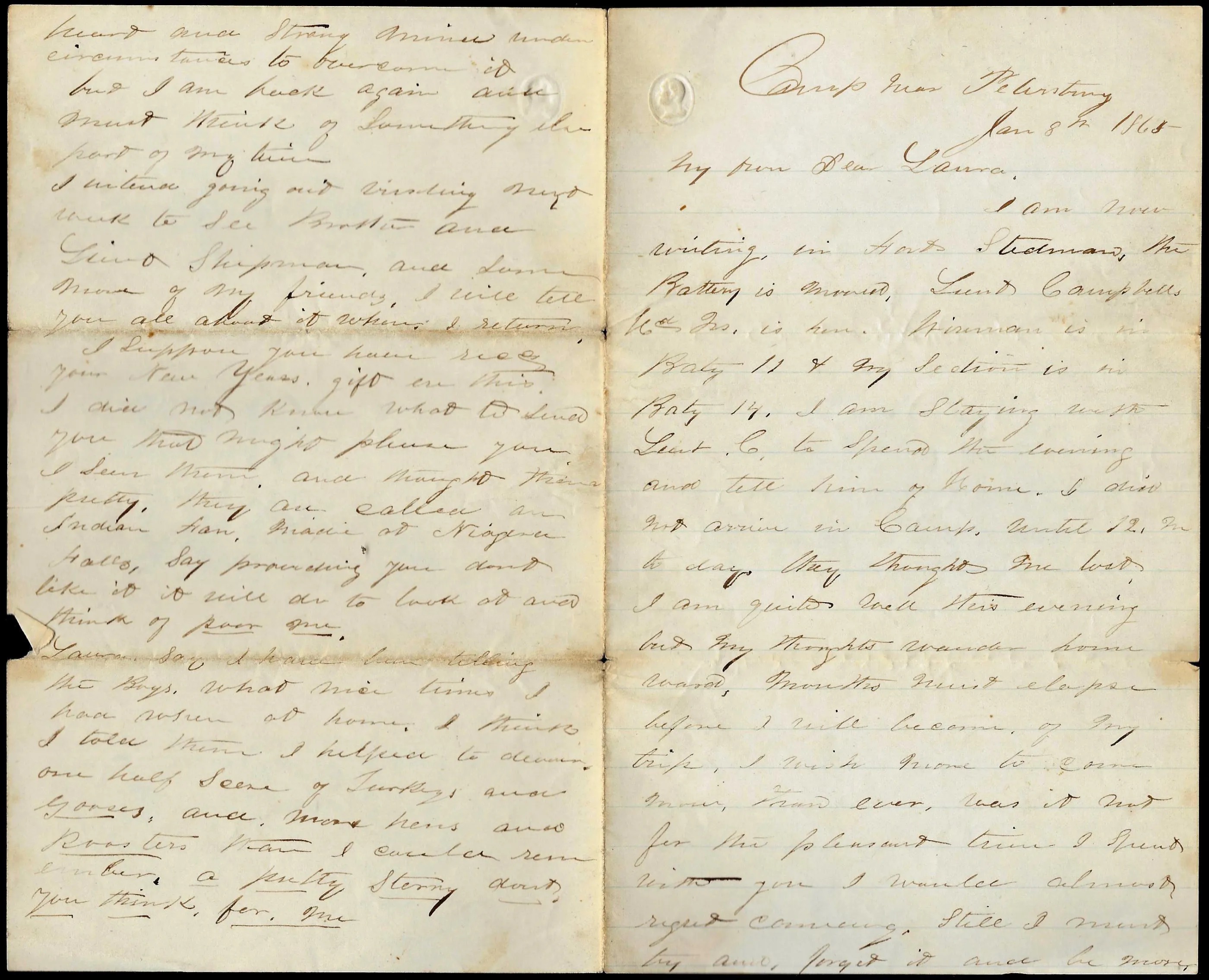

Camp near Petersburg

January 8, 1865

My own dear Laura,

I am now writing in Fort Stedman — the battery is moved. Lieut. [John F.] Campbell, Headquarters, is here. ¹ [Lt. Henry] Wireman is in Battery 11 & my section is in Battery 14. I am staying with Lieut. Campbell to spend the evening and tell him of home. I did not arrive in camp until 12 m. today. They thought me lost. I am quite well this evening but my thoughts wander homewards. Months must elapse before I will become of my trip. I wish more to come more than ever. Was it not for the pleasant time I spent with you, I would almost regret coming. Still I must try and forget it and be more content.

The weather is quite cool but no snow. Mud has been abundant until last night when the ground froze solid. Piquet firing has abated to some extent — quiet prevails along the entire line save an occasional shot fired by some sleepless sentries.

I have no news to relate from the Army. [John] F. Campbell has a bad cold. [Henry] Wireman, I think, is writing a letter to Amelia, and poor W. to L. They have asked so many questions that I am tired. I have declined answering until tomorrow. You should have seen the boys flock around me. I was tired shaking hands. All had questions to ask. Poor fellows — how I wish they could all go home and pass a pleasant time. They seemed to think I had seen all their friends when I had no more than seen a few and breathed the pure air in Old Pennsylvania. That seemed to give them some pleasure and to hear me tell what I had seen and done. I could not tell them all. No neither could I tell them what my sad heart experienced when I paced them ever memorable steps toward the depot and when the train hurried me from her who I so tenderly love. The present crowded my mind to such an extent that I could scarcely overcome them when I gave you the parting kiss. No one could tell what I felt. I could not bear it but I was not unprepared to meet its advent. I thought of returning before I came home and knew it required a stout heart and strong mind under circumstances to overcome it. But I am back again and must think of something else part of the time.

I intend going out visiting next week to see Brother ² and Lieut. [Lemuel] Shipman ³ and some more of my friends. I will tell you all about it when I return.

I suppose you have received your New Years gift ‘ere this. I did not know what to send you that might please you. I seen them and thought them pretty. They are called an Indian fan, made at Niagara Falls. Say providing you don’t like it, it will do to look at and think of poor me.

Laura, say, I have been telling the boys what nice times I had when at home. I think I told them I helped to devour one half score of turkeys and gooses and more hens and roosters than I could remember — a pretty story, don’t you think, for me.

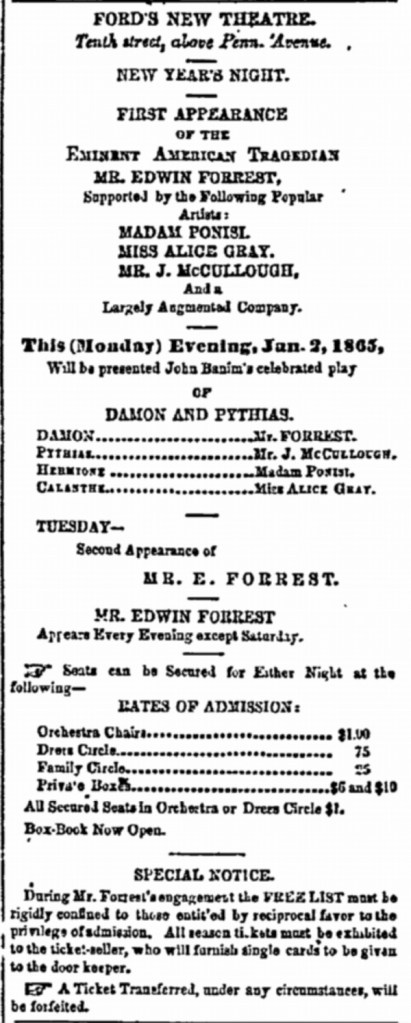

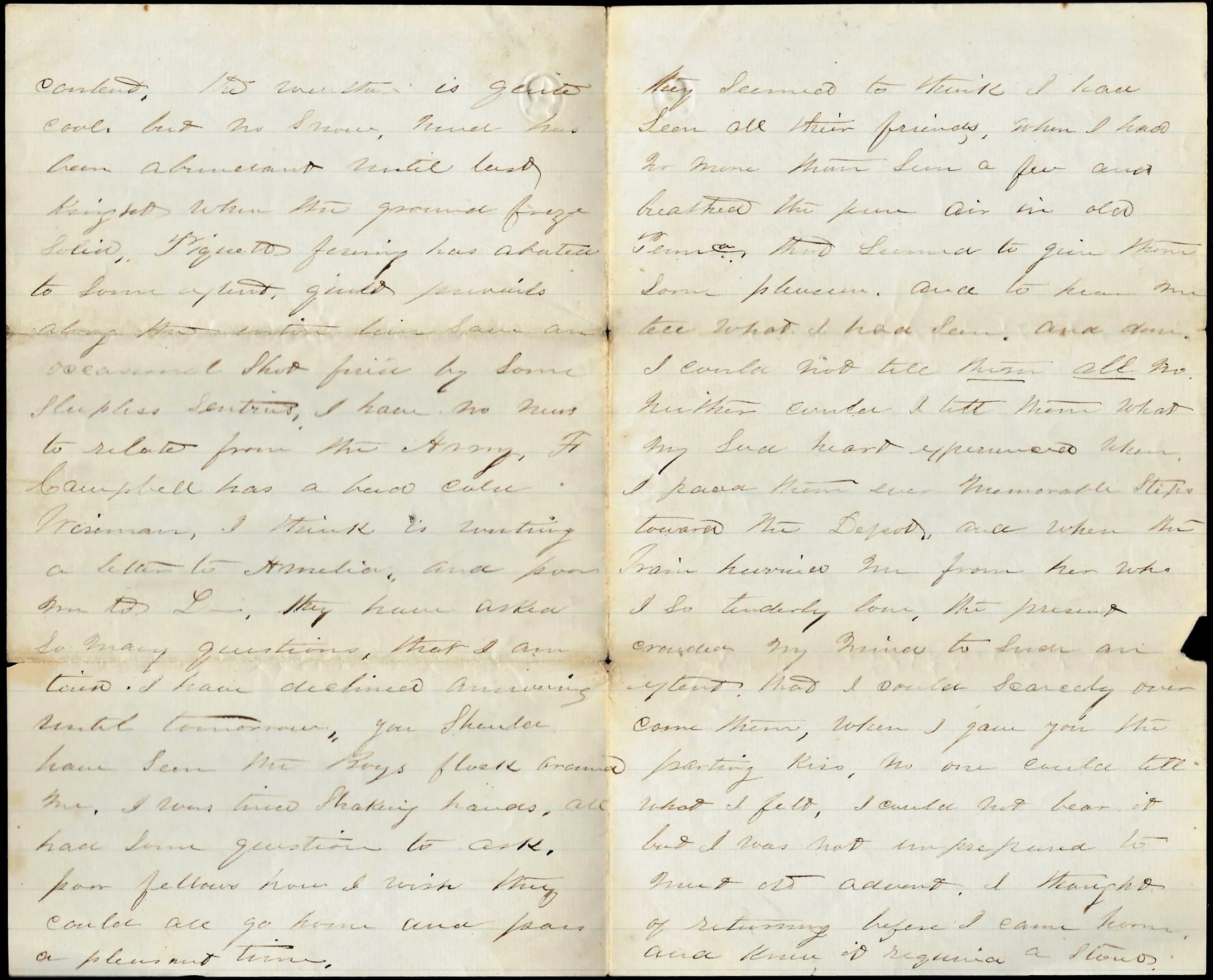

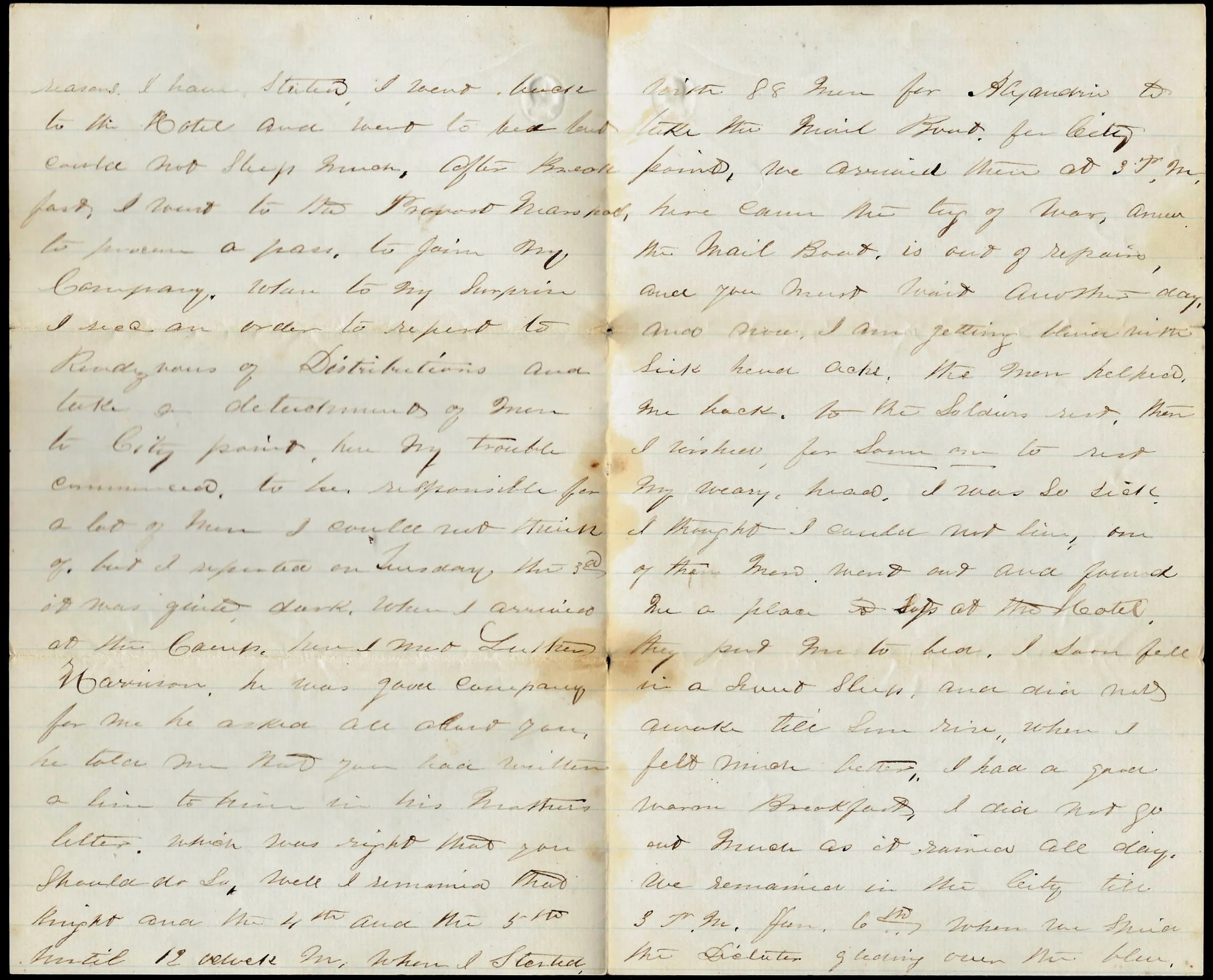

I left Sunday, or Monday morning, 2d January 1865. Did not [feel] well. After a tiresome ride, I arrived at Baltimore by 6½ P.M. I immediately looked after a [omni]bus to convey me to Washington Depot. I did not look long when I heard a darkey cry out at the top of his voice, “Did way for Washington!” I soon found myself quite comfortably seated in a stage coach when the driver cracked his whip and soon landed us safe to our awaiting train. I had scarcely seated myself when the train started. The train arrived there 7½ o’clock. I mounted an [omni]bus and went to the United States Hotel. Supper was waiting. I ate some and then started in company with some officers for Ford’s Theatre. The plays were good but I did not enjoy them for reasons I have stated. I went back to the hotel and went to bed but could not sleep much.

After breakfast, I went to the Provost Marshal to procure a pass to join my company when to my surprise I received an order to report to Rendezvous of Distributions and take a detachment of men to City Point. Here my trouble commenced — to be responsible for a lot of men I could not think of but I reported on Tuesday, the 3rd. It was quite dark when I arrived at the camp. Here I met Luther Harrison. He was good company for me. He asked all about you. He told me that you had written a line to him in his mother’s letter which was right that you should so so. Well, I remained that night and the 4th and the 5th until 12 o’clock m. when I started with 88 men for Alexandria to take the mail boat for City Point. We arrived there [Alexandria] at 3 P.M. Here came the tug of war. A____ the mail boat is out of repair and you must wait another day, and since I am getting blind with sick headache, the men helped me back to the Soldier’s Rest. Then I wished for some one to rest my weary head. I was so sick I thought I could not live. One of the men went out and found me a place to sup at the hotel. They put me to bed [and] I soon fell in a stout sleep and did not awake till sunrise when I felt much better.

I had a good warm breakfast. I did not go out much as it rained all day. We remained in the City till 3 P.M., Jan. 6th when we spied the Dictator gliding over the blue waters of the far-famed Potomac [river]. She moored alongside the Quay and soon we were all on board and off she steamed for Dixie. Soon it grew quite dark, fog commenced to hover around us, and the Captain anchored the boat until the fog disappeared. About 11 A.M. we got under way and the next I knew the boat run aground on a sand bar and here we lay till 9½ A.M., 7th January. After strenuous exertions the boat started on its perilous journey. We soon came out in the Bay [where] the winds seemed to be all abroad [and] dashed against the vessels side, shaking her from stem to stern. She reeled and rolled. The passengers became sick. I was compelled to lie down but our little Bark seemingly was destined to outride the storms which threatened to swallow up our noble little ship with so many precious souls and land in safe on shore. We arrived at City Point at 4 A.M. this morning. O, I was so glad.

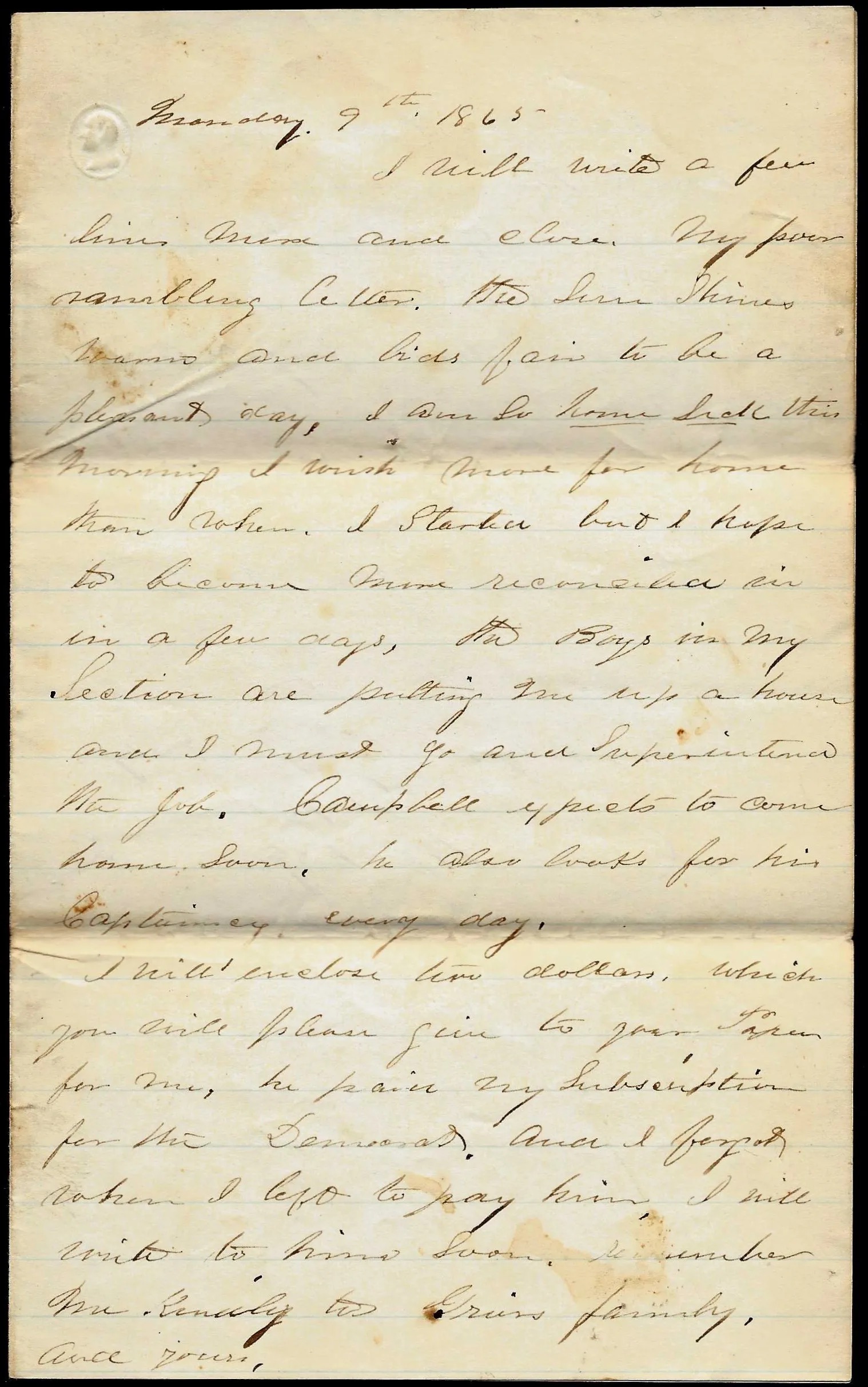

Monday [January] 9th 1865

I will write a few lines more and close my poor rambling letter. The sun shines warm and bids fair to be a pleasant day. I am so homesick this morning. I wish more for home than when I started but I hope to become more reconciled in a few days. The Boys in my Section are putting me up a house and I must go and superintend the job. Campbell expects to come home soon. He also looks for his Captaincy every day.

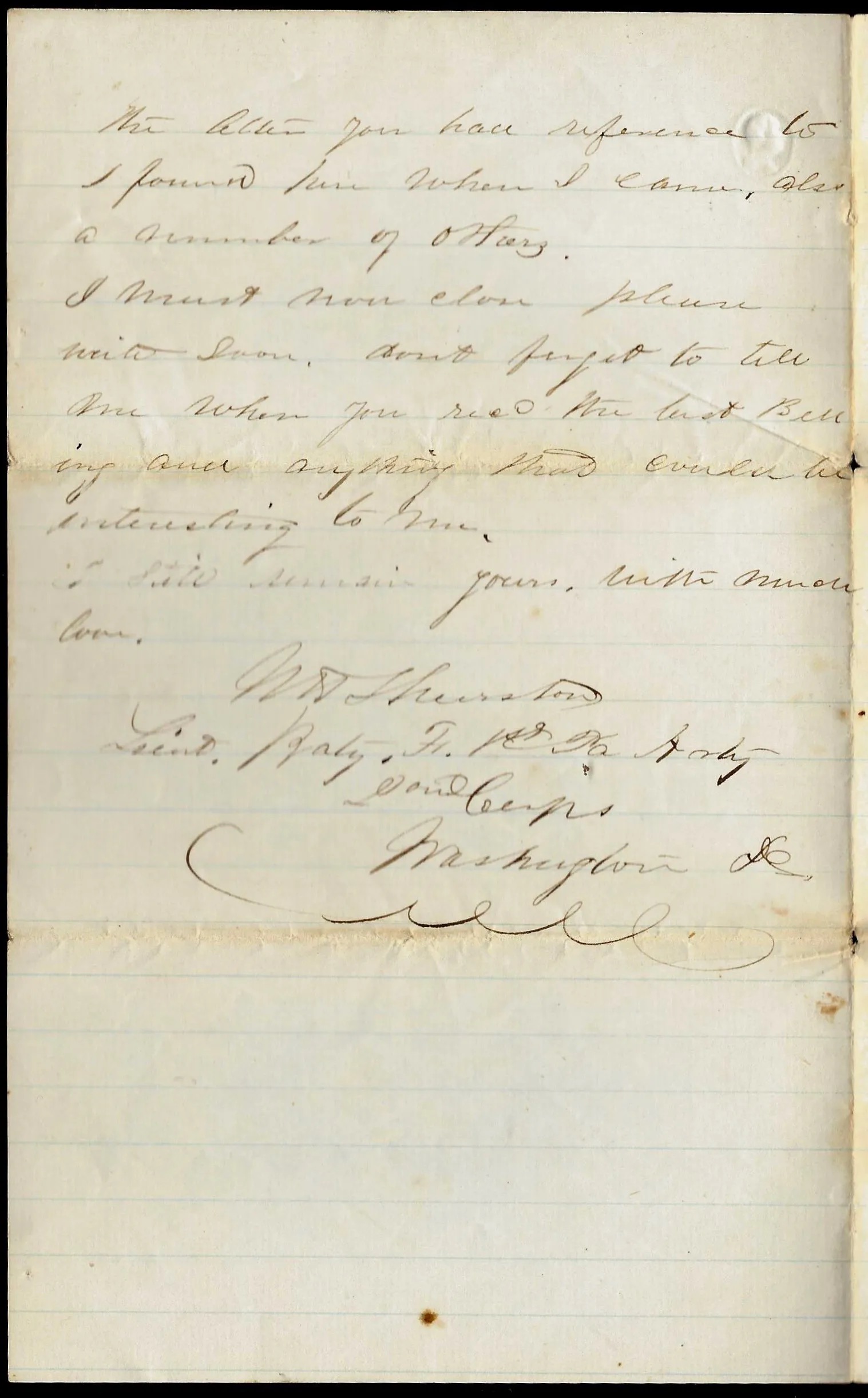

I will enclose ten dollars which you will please give to your Papa for me. He paid my subscription for the Democrat and I forgot when I left to pay him. I will write to him soon. Remember me to Grier’s family and yours. The letter you had reference to I found here when I came — also a number of others.

I must now close. Please write soon. Don’t forget to tell me when you received the last billing and anything that could be interesting to me. I still remain yours with much love. — W. H. Thurston

Lieut. Battery F, 1st Pa. Artillery, 2nd Corps, Washington D. C.

¹ Lt. John F. Campbell (1840-1902) succeeded Ricketts as the captain of the Forty-Third Regiment, Battery F, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery, in April 1865. He is buried in Augustaville, Northumberland county, Pennsylvania. John Campbell was most likely a distant cousin of Laura Morgan’s whose fraternal grandmother was Charity Campbell.

² Possibly Silas Thurston (1842-1923) who served withe “Bucktails” in the 149th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

³ Lt. Lemuel Shipman (b. 1838) of Sunbury, Pennsylvania, entered the service as first sergeant of Co. D, 3d Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery, 152nd Pennsylvania, in October 1862. He was promoted to lieutenant in May 1864.

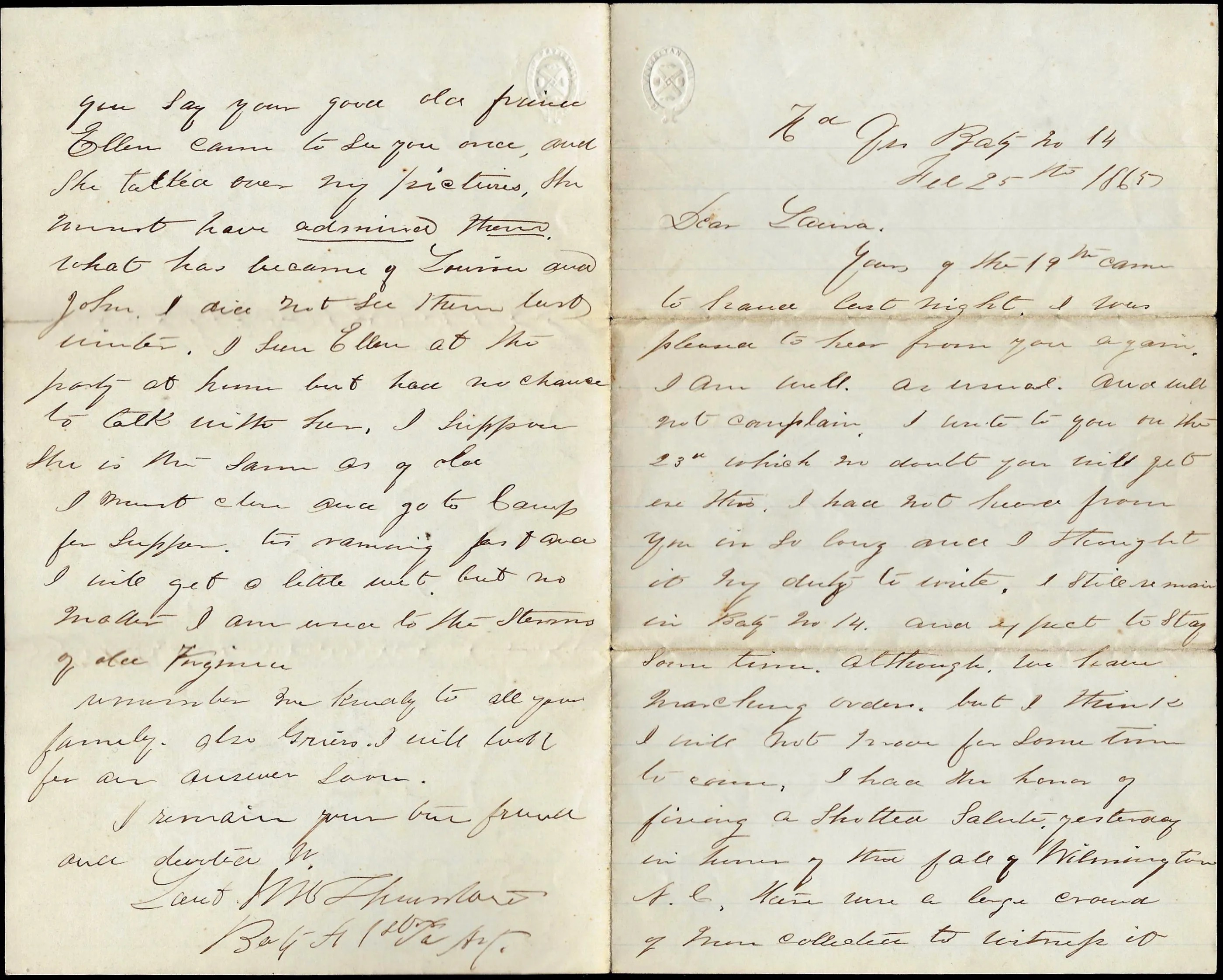

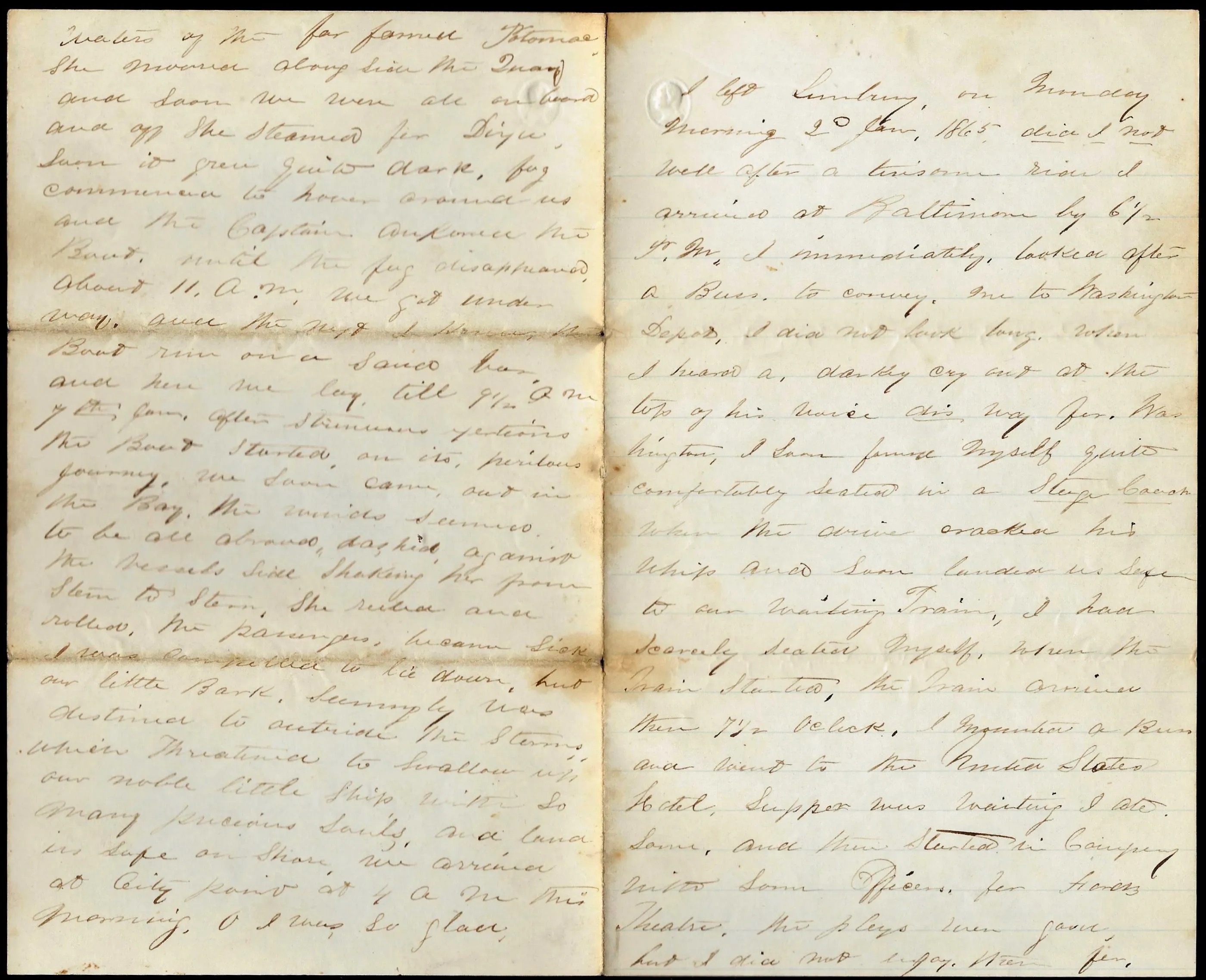

Letter 3

Headquarters Battery No. 14

February 25th 1865

Dear Laura,

Yours of the 19th came to hand last night. I was pleased to hear from you again. I am well as usual and will not complain. I wrote to you on the 23rd which no doubt you will get ‘ere this. I had not heard from you in so long and I thought it my duty to write. I still remain in Battery No. 14 and expect to stay some time although we have marching orders. But I think I will not move for some time to come.

I had the honor of firing a shotted salute yesterday in honor of the fall of Wilmington, North Carolina. There were a large crowd of men collected to witness it. I had no accident and it went all well and good. The Army seems to be in good cheer and I think the next fight we make will be a telling blow to the Rebs. We will have some hard fights but I think ’tis safe to say the end is drawing nigh. The Rebels are deserting by hundreds which must soon deplete their ranks. They are without a doubt hungry and tired of fighting. They are also ragged and dirty with forlorn looks and are objects of pity.

Two men had their heads blown off yesterday close here with mortar shells — members of the 51st Pennsylvania. They lay in their tents sleeping at the time which this death monster fell among them. It was a shell 8 inches in diameter which exploded with a great noise. ¹

I am sorry to hear that Becca B. is not so happy as she once was but I suppose ’tis with them like many others — the honeymoon has past into the shades of oblivion and that long expected life of bliss has not been realized. But this generally happens when least anticipated. Those who think they can best agree soonest dispute and live unpleasant, but I hope ’twill not be so with me and some one.

I perceive you don’t like to sit up at a wake. I have a wake all the time. There are plenty of dead buried only a few feet from my tent that fell on the 17th June 1864, but we are used to this and don’t think of it.

Don’t forget to tell Miss Huldah she had better get them teeth and spell me that answer or I will wool her as __ fate.

You say your good old friend Ellen came to see you once, and she talked over my pictures. She must have admired them. What has become of Louisa and John? I did not see them last winter. I seen Ellen at the party at home but had no chance to talk with her. I suppose she is the same as of old.

I must close and go to camp for supper. ‘Tis raining fast and I will get a little wet but no matter. I am used to the storms of Old Virginia.

Remember me kindly to all your family. Also Grier’s. I will look for an answer soon. I remain your best friend and devoted W.

— Lieut. W. H. Thurston, Batty F, 1st Pa. Art.

¹ One of the two soldiers was John Blyler (1845-1865) who enlisted in Co. G, 51st Pennsylvania in February 1864. He was the son of Absalom Blyler (1803-1863) and Catharine Heimback (1812-1857) of Penns Creek, Snyder county, Pennsylvania. A Certificate of Death for Blyler states that he was “killed by enemy by a piece of mortar shell passing directly through his head while in his tent in camp in front of Petersburg, Va. on February 24th 1865.