The following letter was written by Robert Brooks Terry (1842-1901), the son of William Terry (1814-1863) and Grizzella Brady (1812-1905) of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Robert was married to Ida Jane Piersol, 20 years his junior in 1889.

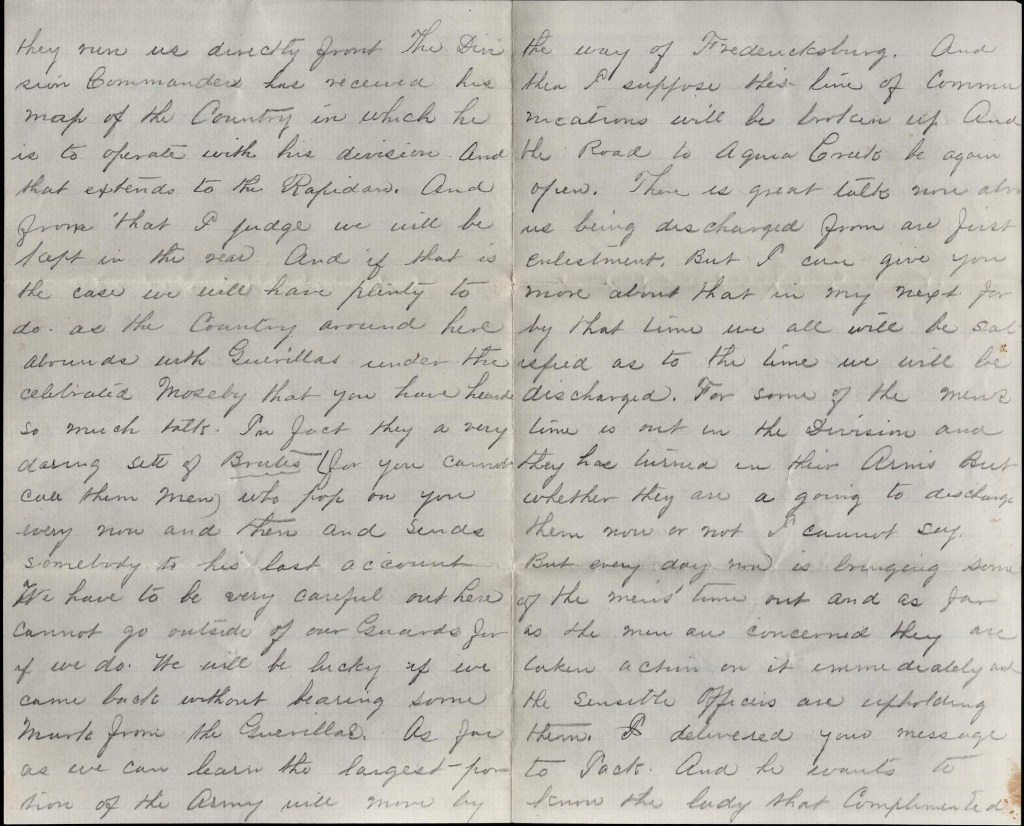

Robert was only 18 years old when he enlisted in June 1861 to serve in Co. K, 36th Pennsylvania Infantry (7th Pennsylvania Reserves). In his letter of April 21, 1864, datelined from a camp near Bristoe Station, Virginia, just two weeks prior to the launch of Grant’s Overland Campaign, Robert conjectured that his regiment wouldn’t see much action. “I judge we will be kept in the rear,” he reassured his sister. He could not have been more wrong. His regiment was in the front lines and heavily engaged in the first day’s action in the Wilderness where they suffered heavy casualties—over 300 killed, wounded or missing. Surrounded and forced to surrender, 272 officers and men in the regiment were taken prisoner and marched to Orange Court House, then to Lynchburg, Virginia. The enlisted men were sent to Andersonville, Georgia, a notorious prison camp, while the officers were sent to Camp Oglethorpe in Macon, Georgia. Robert was one of the “lucky” one to survive the ordeal. He was released on 1 March 1865 and mustered out on 27 April 1865.

Letter 1

Much of the following letter refers to the Battle of Ball’s Bluff which ended badly for the Union army due to poor communication by George McClellan. Readers are referred to the Army Historical Foundation’s article entitled, “Disaster at Ball’s Bluff, 21 October 1861” for a more complete understanding of events.

Camp Pierpont

Fairfax county, Virginia

February 26, 1862

Dear Father,

I received your most welcome letter on the 26th inst. and I was very glad to hear from you. The weather out here now is very good. We had a regular hurricane out here on last Monday but did not damage to anything in this regiment but the tents and it took the majority of them with it. But our tent stood the storm like a rock. It also done a good bit of damage in Washington. Over in the 3rd Regiment, it blowed a tree on a couple of fellows, killing one instantly and breaking both of the legs of the other. I reckon we will be on the move now shortly, maybe inside of the next 2 weeks but I cannot tell exactly.

The Captains gave us new cartridges, 40 rounds to each man, and the orders were to put them in our cartridge box so as to get them out on a double quick. I judge by that that there is a going to be some running besides fighting.

The War Department has sent over about 400 wagons for the use of the division. And that looks like moving. I don’t hardly think we will go beyond Leesburg. We will have the advance till we get to Leesburg. And if we go on to Manassas, Banks will cross at Edward’s Ferry opposite Leesburg and lead on to Manassas. Banks won’t cross till we get on the move and get to Leesburg for they tried it once before and we were ordered there but only got as far as Difficult Creek and was ordered back to camp. And the consequence was that “Stone” sent over Baker’s Brigade which was cut to pieces and Baker himself killed. And what wasn’t killed was taken prisoners. But if we had to kept on, that Balls Bluff affair would never happened. As McCall had his whole division on the move amounting to 15,000 men but was ordered back before he got half way to Leesburg and that both the whole thing.

I heard the news boys a hollering through the camp this morning that Nashville had surrendered. I received a letter from Isiah Bready on last Saturday. He got his situation in the Post Office at Alexander. I expect him up to see me every day as he told me in the letter that he would come up when he gets time. The doctor vaccinated all of us one day last week. He wanted something to do I think. It was to keep us from getting the small pox. I guess I will stop now as I want to say a few words to Lou. Give my best respects to all my friends, &c. From your affectionate son, — Robert B. Terry

Dear Sister [Louisa],

I received your letter on the 24th inst. and was very glad to hear from you. they ought to send the home guards down in this neighborhood for about 3 months. I think it would do the country more good than parading around the streets of Philadelphia. The Rebels at Manassas are 30,000 strong and they are all to die before the place is taken. The other 30,000 they have called away from there & Centerville. If we have the right kind of artillery, it will not take long to take that or Richmond.

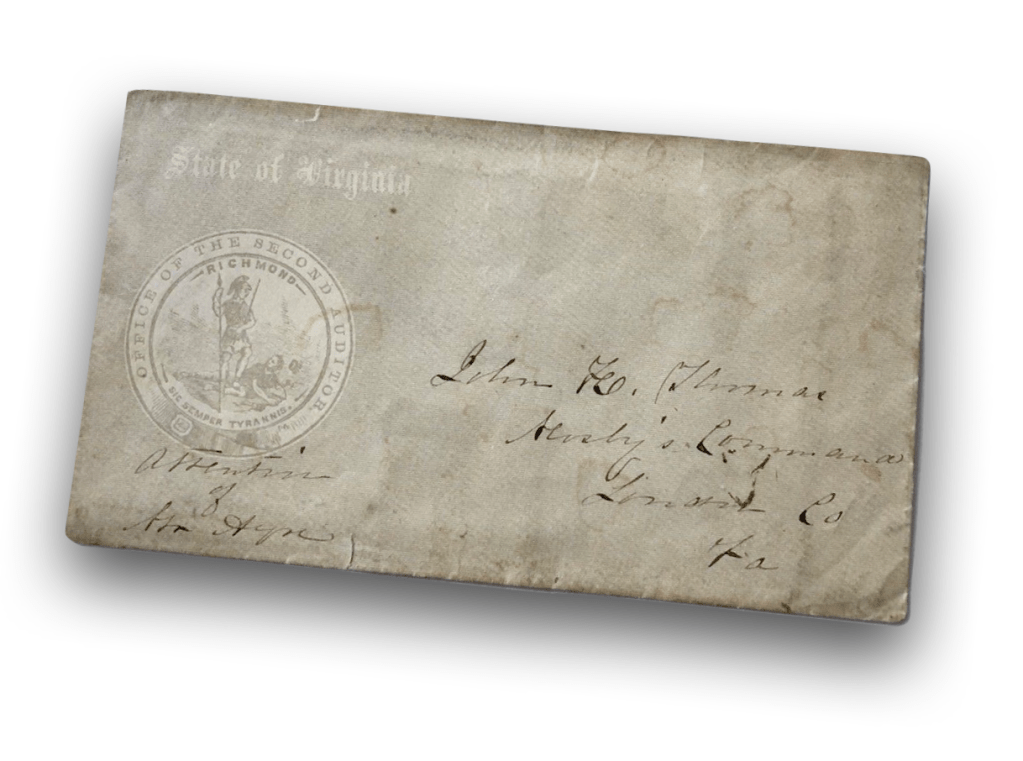

I wrote a letter down to Mr. Willcox on Monday which a messmate of mine, Samuel T. Wilson, and I made up and of which I shall give you an extract of. It is as follows: “To the family of our departed friend and fellow soldier in arms, John H. Willcox [Wilcox]. Whereby it has pleased the Almighty God to remove from our midst our friend and fellow soldier John H. Willcox, we do solemnly mourn his loss. What is our loss is his eternal gain in happiness. He came forth nobly at the call of his country in the vigor of manhood to battle against its enemies, little thinking then that before htis great Rebellion would be over, that he would be called to his final resting place. No more will he meet in our midst as we gather around our camp fire or hear his cheerful voice as that tongue is silent. But weep not for him friends as he is at rest. Though no mother or father was near to soothe his brow or no sister to support his dying head, but friends were there who loved him dearly. His amiable disposition and character gained him many friends, None knew him but loved him. Missed he will be in the family circle. But we will miss him more while engaged in the great struggle. When peace smiles once more on our country and we receive the order to return to our beloved homes, then we shall miss him for he will not be with us to share our happiness. But when you. think of him, think then he offered his life upon his country’s alter, sacrificed all to endure the horrors of a battlefield, fatiguing marches, and the misery of a camp life. He has paid the last debt of nature and he now rests till the trumpet of the archangel shall call him forth to meet his God. There let us all endeavor to meet and be happy. — Robt. B. Terry

P. S. Direct in care of Captain [James M.] Rice as the boys elected him Captain. [Casper] Martin has resigned and went home. We have not got marching orders. Three. days rations in our haversacks and ready to march at a minute’s notice. I expect we will go tonight or early in the morning and the order is that when once on the road again, we won’t come back till driven back by an overwhelming force. — R. B. Terry

Letter 2

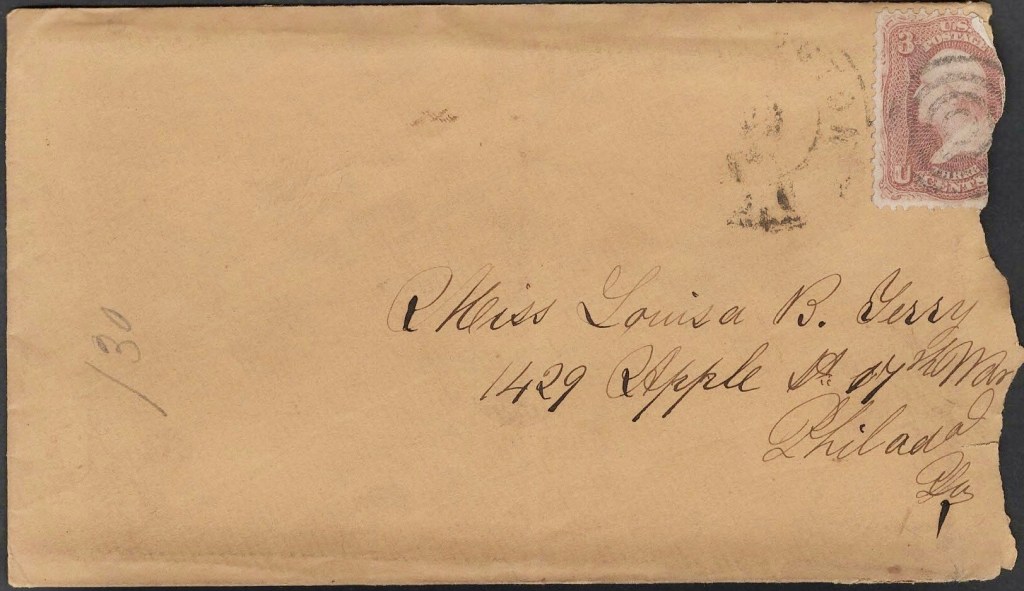

Robert wrote the letter to his younger sister, Louisa B. Terry (1844-1865) who was employed as a 21 year-old school teacher in Philadelphia at the time of her death on 5 December 1865.

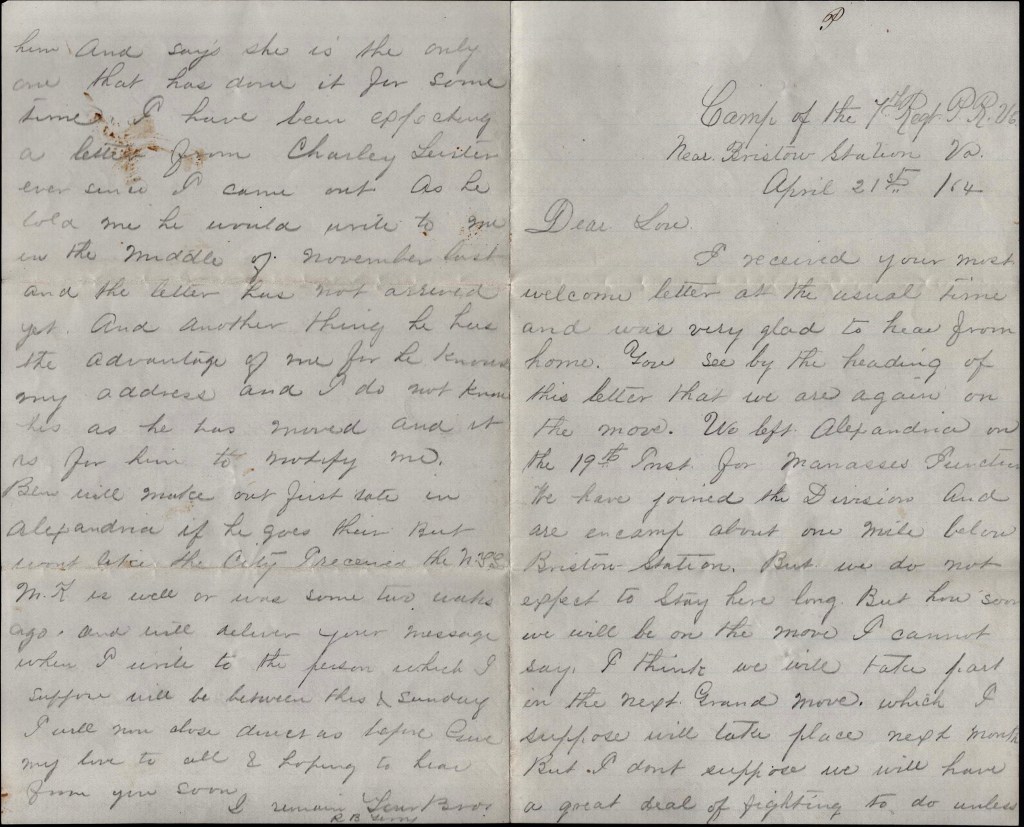

Camp of the 7th Regt. P. R. V. Infantry

Near Bristoe Station, Va.

April 21st 1864

Dear Lou,

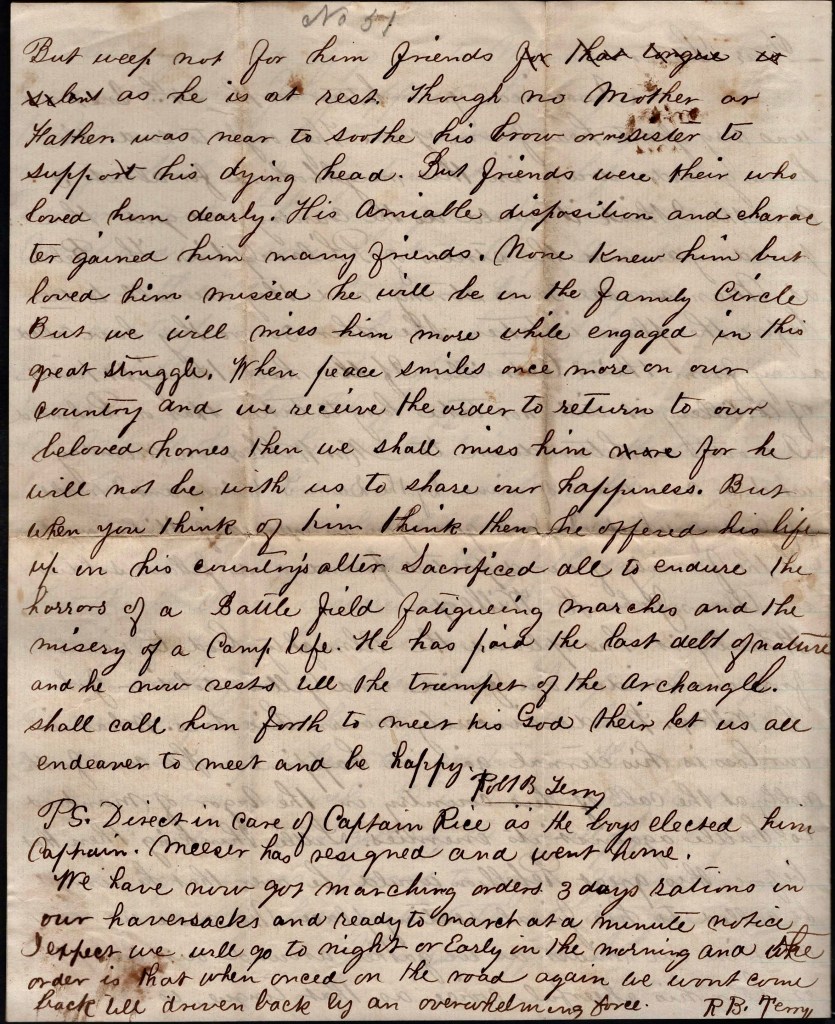

I received your most welcome letter at the usual time and was very glad to hear from home. You see by the heading of this letter that we are again on the move. We left Alexandria on the 19th inst. for Manassas Junction. We have joined the Division and are encamp[ed] about one mile below Bristoe Station. But we do not expect to stay here long. But how soon we will be on the move, I cannot say. I think we will take part in the next grand move which I suppose will take place next month. But I don’t suppose we will have a great deal of fighting to do unless they run us directly front.

The Division commander has received his map of the country in which he is to operate with his Division and that extends to the Rapidan. And from that, I judge we will be kept in the rear. And if that is the case, we will have plenty to do as the country around here abounds with guerrillas under the celebrated Mosby that you have heard so much talk. In fact, they [are] a very daring set of brutes (for you cannot call them men) who pop on you every now and then and sends somebody to his last account. We have to be very careful out here—cannot go outside of our guards for if we do, we will be lucky if we come back without bearing some mark from the guerrillas.

As far as we can learn, the largest portion of the Army will move by the way of Fredericksburg, and then I suppose the line of communications will be broken up and the road to Aquia Creek be again open.

There is great talk now about us being discharged from our first enlistment but I can give you more about that in my next for by that time we all will be satisfied as to the time we will be discharged. For some of the men’s time is out in the Division and they has turned in their arms. But whether they are a going to discharge them now or not, I cannot say. But every day now is bringing some of the men’s time out and as far as the men are concerned, they are taken action on it immediately and the sensible officers are upholding them.

I delivered your message to Jack and he wants to know the lady that complimented him and says she is the only one that has done it for some time. I have been expecting a letter from Charley Leister ever since I came out as he told me he would write to me in the middle of November last and the letter has not arrived yet. And another thing, he has the advantage of me for he knows my address and I do not know his as he has moved and it is for him to notify me.

Ben will make out first rate in Alexandria if he goes there but won’t like the city. I received the N. Y. T. [New York Tribune]. M. K. is well or was some two weeks ago and will deliver your message when I write to the person which I suppose will be between this and Sunday. I will now close. Direct as before. Give my love to all & hoping to hear from you soon, I remain your brother, — R. B. Terry