The following letter was penned by Orange Merwin (1777-1853) in February 1828 while serving in the 20th US Congress as a Representative of Connecticut. Merwin was born near Milford, in Litchfield county, where he attended the common schools and “engaged in agricultural pursuits” until 1815 when he won a seat in the State House of Representatives and later in the State Senate. He was a member of the committee charged with redrafting the state constitution during that time. In 1825 he was elected to the 19th US Congress and served through the 20th. After leaving Congress he returned to Connecticut and resumed farming. Merwin wrote the letter to his friend, Daniel H. Gaylord (1776-1831) of Milford, Connecticut.

Merwin’s letter expresses considerable frustration by the lack of progress in the business of Congress over the previous ten days occasioned by the political speeches on the House floor by representatives of the two political parties for or against the Democratic candidate Andrew Jackson who would win the Presidential election later in the year against incumbent John Quincy Adams. “A long time was spent in debating whether Congress were bound to pay for a negro slave who was pressed into the public service at New Orleans during the late war [War of 1812] and was injured.” The debate transformed into a spectacle of speeches either eulogizing or vilifying the character of Andrew Jackson, the so-called “Hero of New Orleans,” completely sidelining any meaningful discussion of the bill at hand.

I can’t find any evidence that Congress ever made a decision on the Bill, but even if it had awarded compensation, it’s important to recognize that any compensation would have been awarded to the slave owner for his financial injuries, not to the slave for his physical injuries. Many of the slaves who were pressed into service by Andrew Jackson in the defense of New Orleans were promised their freedom so they fought fiercely and suffered grave injuries or even death. But once victory was secured, Jackson not only ordered the black troops out of New Orleans because they frightened the white residents, he reneged on his offer to free them and ordered them returned to their slave owners. [See Enslaved Soldiers and the Battle of New Orleans by the Tennessee Historical Society.]

In the letter, Merwin refers to the slave as “Cuff,” which was a common ethnic slur referring to a male negro in the early 19th Century.

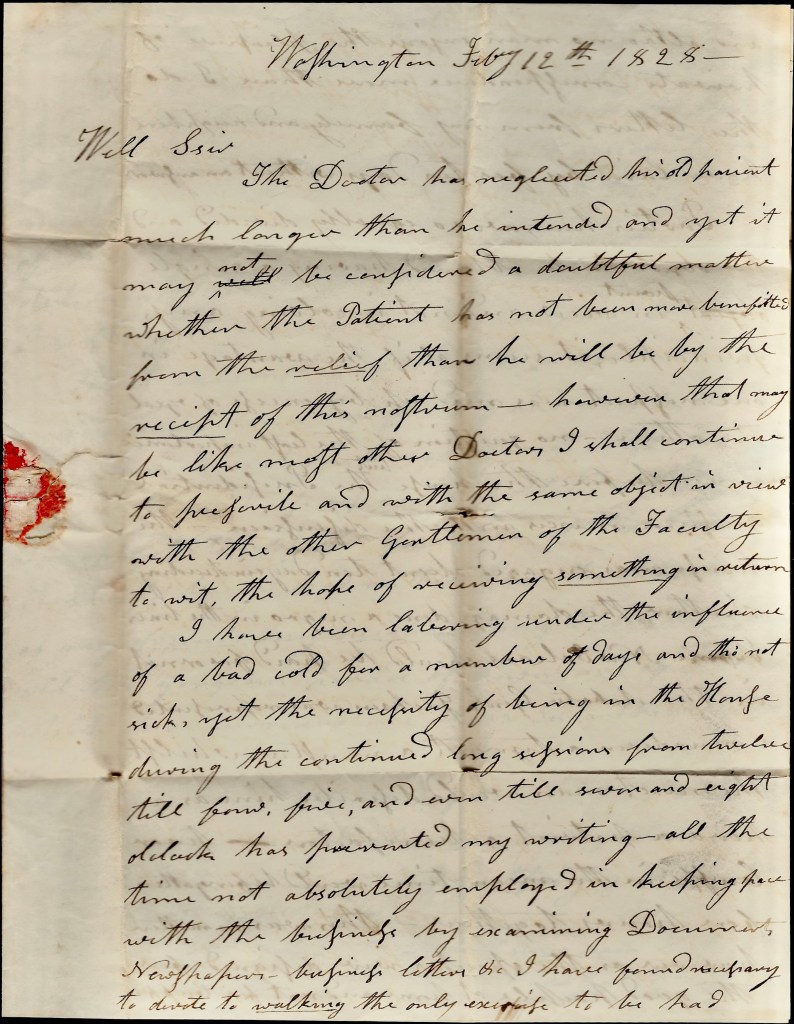

Transcription

Washington

February 12th 1828

Well Sir,

The Doctor has neglected his old patient much longer than he intended and yet may not be considered a doubtful matter whether the patient has not been more benefitted from the relief that he will be by the receipt of this nostrum—however that may be like most other doctors, I shall continue to [ ] and with the same object in view with the other Gentlemen of the Faculty to wit, the hope of receiving something in return.

I have been laboring under the influence of a bad cold for a number of day and though not sick, yet the necessity of being in the House during the continued long session from twelve till four, five, and even till seven and eight o’clock has prevented my writing—all the time not absolutely employed in keeping pace with the business by examining documents, newspapers, business letters, &c. I have found necessary to devote to walking the only exercise to be had and although no man enjoys the pleasure of private correspondence more than I do, the letters from my family and neighbors have lain by for ten days without an answer.

Parties here are so equally divided and the object to be obtained having a single point in view and not involving any principle, it seems as if the vantage in one respect was made up by excess of zeal in the other. No question of the least importance comes before the House but the Presidential question mixes with the discussion. The House was engaged about ten days in deciding whether the damage done a negro in the lines before New Orleans should be paid for or not. In the debate, Gen’l Jackson was represented a murderer, a tyrant, a monster, whilst the next man would describe him as a hero, a patriot, a benefactor. Poor Cuff in the meantime would be forgotten for hours together. This was no matter, however, as the speeches were designed for the good people at home and not for Cuff.

February 13th. This is the third time I have attempted to write you a letter. I think I shall now make out to finish it without interruption as it is scarcely day break and the idle habits as well as visiting formalities of this place will prevent an early call and I am determined not to forfeit my new title even though I sustain it at the loss of some necessary sleep.

What will not ambition do? —voluntarily exile a man from his family and friends that he may have a seat in Congress—not satisfied, not get up late and rise up early to obtain and seek the approbation of his friends. Well, this is just as it should be. I had rather have the approbation of my friends, my neighbors, my townsmen, than all the gorgeous parade of power and of place which have surrounded me—yes sir, and the recollections of this kind will long continue when the offices which I now hold shall cease to exist, and be lost to all value except the manner of their attainment.

Respectfully your friend

P. S. Tell Alvent I hope he has long since been keeping house and riding in the mud and hub to Bridgewater after—council