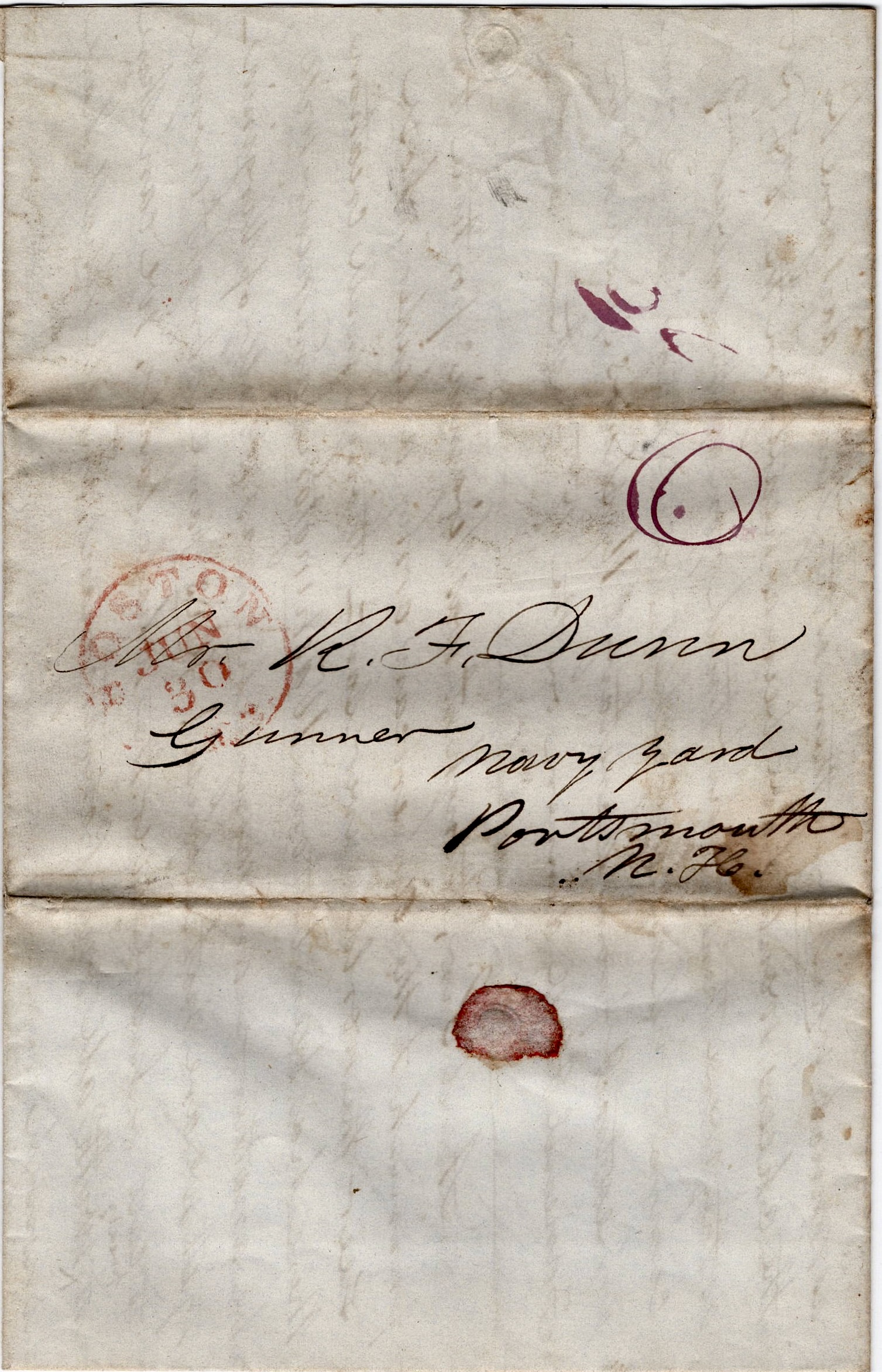

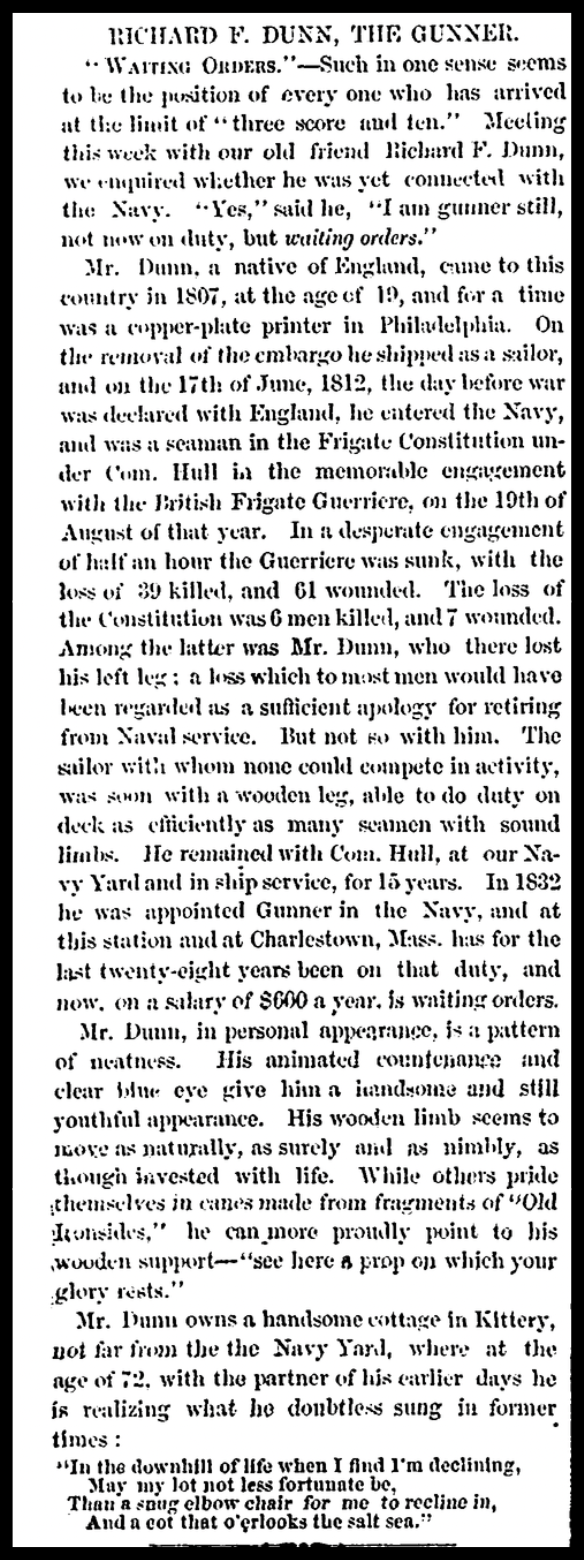

The author of this letter is believed to have been Nehemiah Nelson (b. 1806-1861) who kept a grocery store at 41 Commercial Street in Boston. He wrote the letter to Richard Fletcher Dunn (1788-1863), a native of Northumberland, England, who came to the United States in 1807 and worked as a copper-plate printer in Philadelphia until joining the merchant service in 1809 (with a fraudulent certificate of citizenship).

He then signed up for the US Navy and participated in the War of 1812, serving aboard the USS Constitution under the command of Capt. Isaac Hull. He was on board during the engagement with the British frigate HMS Guerriere on the 19th of August 1812—an engagement that last more than half an hour resulting in the sinking of the HMS Guerriere and the loss of 39 crew members killed and 61 wounded. The USS Constitution, on the other hand, suffered little damage, thus earning her the nickname “Old Ironsides.” She suffered the loss of only 6 crew members and 7 wounded. Among the latter was Dunn who lost his left leg, blown off by a cannon ball.

Though lesser injuries might have warranted retirement from the service of his adopted country, Dunn remained steadfast in his commitment to the Navy, ultimately serving at the Kittery Navy Yard. He continued to serve under Capt. Hull (later Commodore Hull) at the Navy Yard, performing his duties on a wooden leg “as efficiently as many seamen with sound legs.” According to the 1860 US Census, he was still listed at Kittery, York County, Maine, with his occupation recorded as “Gunner, USN.” When inquired that year about his ongoing connection with the Navy, he replied, “Yes, I am gunner still, not now on duty, but awaiting orders.” He passed away on 1 February 1863, and his widow, Mary F. (Dixon) Dunn, died in 1872. They are buried in Eliot, Maine.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Boston [Massachusetts]

June 29, 1843

Friend Dunn,

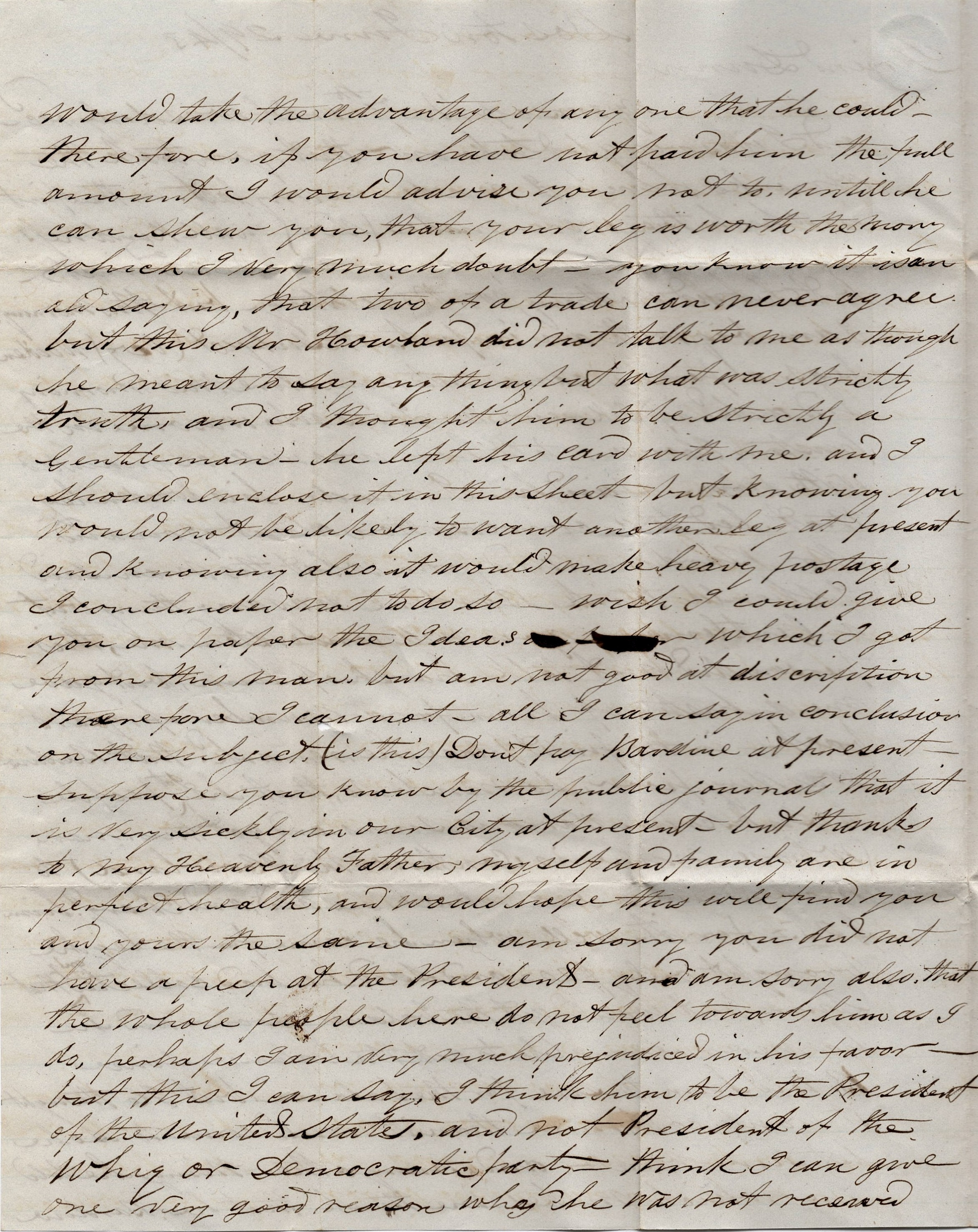

Yours of the 7th inst. was duly received and I was very glad to know that you took the remarks which I made in my last in the spirit in which they were made (viz) in all kindness. You said a letter from on the 22nd inst. but I had nothing worth relating. But this morning I am big with an important subject (viz) wooden legs.

A person came into my store this morning and asked if I knew Mr. Jones who was once in the Custom House. I told him I was well acquainted with him. Said he, I made his wooden leg. That led to a conversation about you and Mr. Bardine, and from what this man said, I should think Mr. Bardine was anything but a gentleman. You will understand me, this person did not talk harsh of him, but gave me a history of him for a number of years back.

In the first place, he remarked that Bardine was very poor, so much so that he got people to subscribe various sums and got this man (whose name is Southworth Howland 1 ) to make him a leg which he did and charged him $25 for it. Well, when he came for the leg, he brought only $20 and said he had collected only that sum, but would get the balance since Bardine told him to sue for the balance. But Howland thought it would cost more than it would come to so he let him run. And many other things he told me which makes me think that he—Bardine—would take the advantage of anyone that he could. Therefore, if you have not paid him the full amount, I would advise you not to until he can show you that your leg is worth the money which I very much doubt.

You know it is an old saying that two of a trade can never agree but this Mr. Howland did not talk to me as though he meant to say anything but what was strictly truth, and I thought him to be strictly a gentleman. He left his card with me and I should enclose it in this sheet, but knowing you would not be likely to want another leg at present and knowing also it would make heavy postage, I concluded not to do so, Wish I could give you on paper the ideas which I got from this man, but I am not good at description—therefore, I cannot. All I can say in conclusion on the subject is this. Don’t pay Bardine at present.

Suppose you know by the public journals that it is very sickly in our City at present. But thanks to my Heavenly Father, myself and family are in perfect health, and would hope this will find you and yours the same.

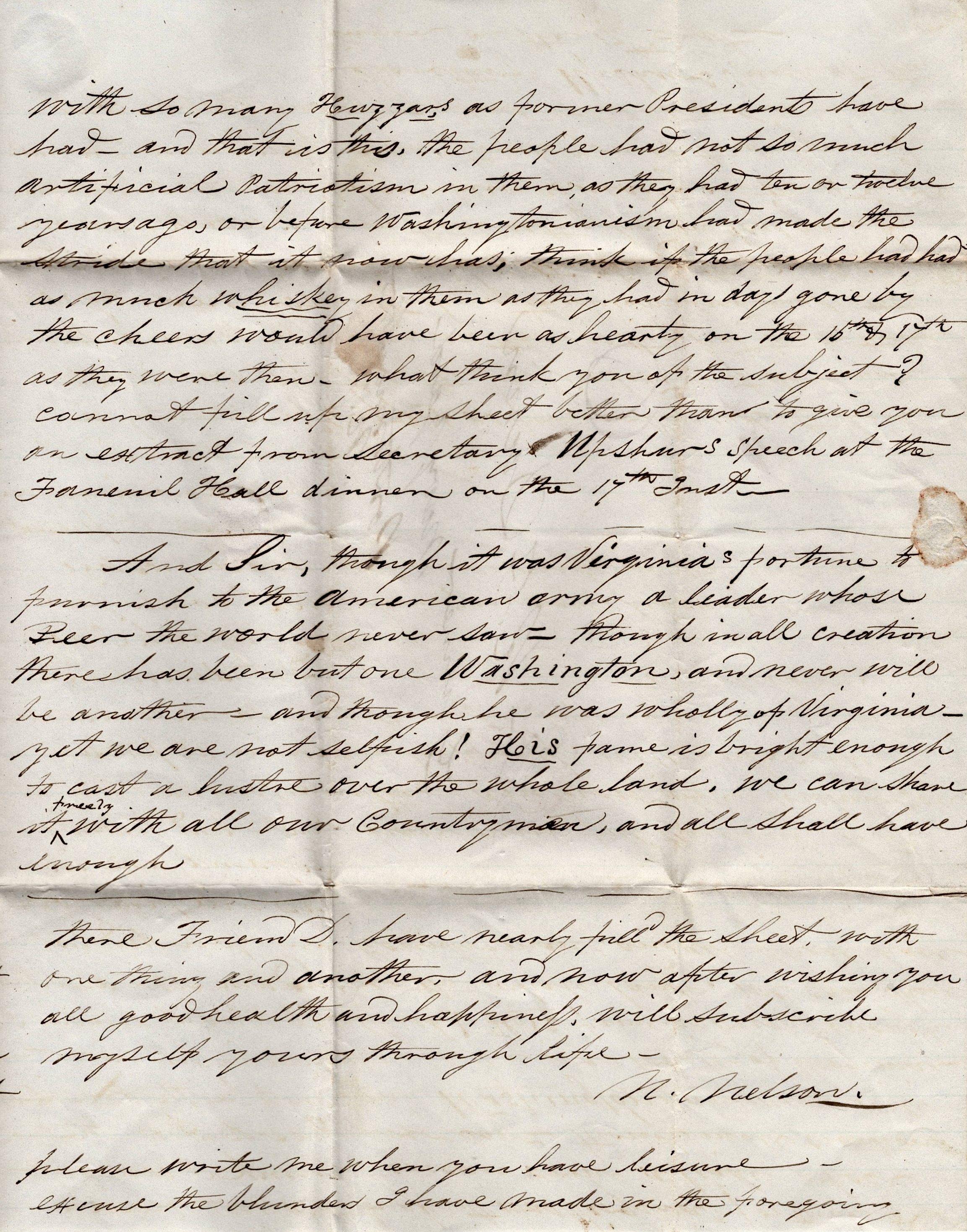

Am sorry you did not have a peek at the President [John Tyler] and am sorry also that the whole people here do not feel towards him as I do. Perhaps I am very much prejudiced in his favor. But this I can say, I think him to be the President of the United States and not the President of the Whig or Democratic party. Think I can give one very good reason why he was not received with so many huzzah’s as former Presidents have had and that is this—the people had not so much artificial patriotism in them as they had ten or twelve years ago, or before Washingtonianism had made the stride that it now has. Think if the people had had as much whiskey in them as they had in days gone by, the cheers would have been as hearty on the 15th and 17th as they were then. What think you of the subject? 2

Cannot fill up my sheet better than to give you an extract from Secretary [Abel C.] Upshur’s [Secy. of Navy] speech at the Faneuil Hall dinner on the 17th inst.

“And Sir, though it was Virginia’s fortune to furnish to the American army a leader whose peer the world never saw, though in all creation there has been but one Washington, and never will be another, and though he was wholly of Virginia, yet we are not selfish! His fame is bright enough to cast a luster over the whole land. We can share it truly with all our countrymen, and shall have enough.”

There, friend Dunn, have nearly filled the sheet with one thing and another, and now after wishing you all good health and happiness, will subscribe myself yours through life. — N. Nelson

Please write me when you have leisure. Excuse the blunders I have made in the foregoing.

1 Southworth Howland (1775-1853) learned the house carpenter’s trade but, being “an ingenious and skillful workman and was often called on to do jobs not entirely in the line of his trade. One of these was to alter and fit an artificial leg, imported from England by a neighbor; but he found it easier to make a new one, with such improvements as gave satisfaction to the wearer. His success became known, and during the next forty years he was called on to furnish artificial limbs for a large number of men and women residing in all parts of the United States, no other person manufacturing them in this country, so far as known, for many years after. He was a man of decided convictions and was prompt and fearless in defending them.”

2 This is a reference to the Washingtonian movement that was in full swing in the 1840 as were many other “ism’s.” The Washingtonian movement evaporated within a few short years. They became embroiled in the politics of the day. They were a victim of their own decision to support the elimination of all drinking in the US in that era through the temperance movement.